Abstract

We propose a partial theory explaining the processing of opportunities by individuals in organizations, specifically for opportunities with both commercial and moral significance (measured as intensities). The goal of such theorizing is to identify and analyze the range of interactions that the ethical and economic impacts of an opportunity can have so that managers can make better decisions on their exploitation and modification. We explain why and how there is variance in the processing of the ideas behind such opportunities as caused by their moral and commercial intensities. We explain the likely interactions between those two intensities, and when they occur and what can result. Doing so complements work in social entrepreneurship and corporate social responsibility by filling the gaps of the possible combinations of economic and ethical interactions. We provide these explanations by leveraging a precedent model that had adapted a standard knowledge-processing method to ethical decision-making issues. The explanations resonate because our model leverages the traditional textbook entrepreneurship opportunity evaluation criteria to provide a holistic view of an underlying idea’s commercial intensity, a view that aligns with the driving assumption that the focal decision-makers are boundedly rational.

1. Introduction

There is no innovative activity in society without individuals recognizing, assessing and exploiting new ideas to create value for others. So, increasing the understanding of how individuals process the ideas that underlie those opportunities is vitally important (Wood and McKelvie 2015). Ideas-as-opportunities vary in their economic attraction in many ways, including in ways that are independent of the parties evaluating them (Haynie et al. 2009; Plummer et al. 2007). Further, many commercial opportunity ideas also entail moral implications, and so an additional level of understanding is needed to process that impact on decisions (e.g., Jones 1991; Shaw and Barry 2015; Strong and Meyer 1992). When an idea that holds both economic and ethical attraction is enacted, it is considered as social enterprise activity. Such activity is important because it provides the means to improve humankind’s welfare, either as part of an organization’s social contract with its community, or beyond it, most often by adding new value to disadvantaged people and to areas of a distressed planet. Our contribution is a new partial theory of behavior in idea assessment to comprehensively address the cases when opportunities possess potentially both significant commercial and moral impacts, and to offer an explanation for how such opportunities are acted upon when tradeoffs between them exist. Our goal is to identify and analyze the range of interactions and tradeoffs they can have so that a manager can make better decisions on their exploitation and modification of such opportunities.

In the general sense, all organizations exist because they partake in both socially and economically beneficial activities. To survive in the long run, they must provide at least minimal commercial returns to their investors, with at least minimally differentiated offerings to their consumers, and at least minimal perceived level of moral returns (e.g., meeting legal standards) to their communities. At their best, those returns are significant and embodied in an enterprise that combines both the social stakeholder and the shareholder value creation synergistically (e.g., Grameen Bank), solving a current societal need with a market-based mechanism in an economically and environmentally sustainable manner (Nicholls 2008). At their worst, social returns are negative and traded off for positive economic ones (e.g., Turing Pharmaceuticals, Ford Pinto, and so on).

It is widely understood that there are many ideas that can lead to opportunities to do good, well, or both; moreover, it is a challenge for our field to analyze such phenomena in order to prescribe how organizations can better find, evaluate and exploit such ideas. One large part of that challenge is dealing with the heterogeneity involved—whether it is in the inputs (e.g., the ideas and people involved) or in the outputs (e.g., the success levels of the exploited opportunities). In order to make progress on the challenge here, we focus on the heterogeneity in the opportunities that individuals in the organizations identify, judge and act upon and that carry commercial and moral weight. That focus allows us to analyze the effects of such heterogeneity on the process of turning ideas into behaviors by the decision-maker and her organization. In turn, that analysis provides a solid basis for predictions and understanding about that phenomenon. In addition, the model provides a benchmark for potentially controlling the phenomenon when actual performance varies from it. We believe that these are useful contributions to the literature on this phenomenon because, for example, they allow us to answer the research question of why not all opportunities, especially social business opportunities, are processed in the same manner (i.e., because that processing varies by the potential impacts of the commercial and moral issues involved).

The partial theory we propose sets a benchmark, explains variance in a process and takes a complementary perspective to alternative models of ideas and entrepreneurs. It forms the basis for four new propositions that predict patterns for the phenomenon in question, several of which are wholly new regarding the effects of the interactions of the moral and commercial intensities of opportunities. (An intensity being a holistic measure of the multidimensional, proportional importance of an opportunity’s idea from an ethical or economic lens.1) The partial theory is coherent, grounded in an established analysis framework, and is novel in its insights into the complexity of opportunities. It answers the calls for research on opportunity evaluation when morality matters (e.g., Scheaf et al. 2020, p. 23). It answers the calls for research in managing paradox in such entrepreneurial activities, including through different theoretical perspectives (e.g., Smith et al. 2013, p. 426, 431). It informs the still-evolving opportunity evaluation research stream, focusing on mental models and integration of goals, and confronting the ethical issues that that stream has avoided (Wood and McKelvie 2015). Our theorizing introduces a new multi-dimensional construct of opportunity attractiveness built on paralleling an existing moral evaluation construct, one that is consistent with (yet extending) a recent multi-dimensional construct integrating 49 previous related concepts in the literature (Scheaf et al. 2020); this simplifies the analysis of the interactions between moral and economic concerns.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Related Literature

We believe that it is valuable to consider ethical and commercial decision making together. While some of the social entrepreneurship research addresses such combined decision making, even that work is often focused on a different question—i.e., starting with the presumption of high moral intensity, it asks why such ideas are not acted upon with resource commitments by organizations (and then it frequently attempts to identify economically sustainable ways to do so, e.g., El Ebrashi 2013; Yunus 2006). That is a more specific question than which we ask, and one without the structure we are assuming for the process. A similar argument can be made for the corporate social responsibility (CSR) literature relating to decision making—it also considers a more specific question that begins with the assumption of high moral intensity (if not high commercial intensity as well—e.g., McWilliams and Siegel 2001). Stakeholder theory (e.g., Donaldson and Preston 1995) also relates to the decision making considered here, but again in a less structured and more focused manner (e.g., based on conflicts across interests). To complement these perspectives, we offer a comprehensive model that considers all combinations of the main levels of intensity and their benefit–harm profiles in a structured setting.

We do so because decisions combining commercial and moral intensities are important to a wide range of decision-makers involved in business and society (Fiet 2007). We choose to model the interactions between these intensities as interdependently complex rather than as independent, mediating or moderating in nature. We do so because the existing literature: supports the direct impact of each intensity (e.g., Jones 1991; Cannatelli et al. 2019; Gruber et al. 2015); provides examples of innovations targeted at aligning those intensities (e.g., Battilana and Dorado 2010; Porter and Kramer 2006; Yunus 2006); reveals overlaps in the dimensions of the two intensities (e.g., in terms of proportionality issues—McMahon and Harvey 2007; Baron and Ensley 2006); and describes how they are processed (e.g., Rest 1979; Cohen and Levinthal 1990). Such a variety of depictions implies the need for modeling that is not simple, but multi-case, as we provide.

Our analysis below complements the literatures on phenomena where the economic and ethical logics at a firm need to be carefully managed—in social entrepreneurship activities (e.g., Smith et al. 2016; Zhao and Lounsbury 2016), with corporate ethics (e.g., Valentine et al. 2011; Valentine and Godkin 2019), in hybrid firms (e.g., Battilana and Dorado 2010), and even in the controversial economy firms (e.g., Cannatelli et al. 2019).2 Our analysis suggests that opportunities need to be assessed comprehensively—across their multiple intensities simultaneously—in order to make the best decisions on whether to pursue them and how.

In order to get to the intensity-combined decision making, we first argue that the Jones (1991) Model can be paralleled from the ethical to the commercial case, and then we argue for a merged model that includes the effects of both moral and commercial intensities together on the issues that real individual decision-makers in their organizations face. As such, the theoretical foundation for our contribution lies in the following precedent model described now.

2.2. The Jones Model of Intensity Effects

Jones’s (1991) proposed model of the moral behavior of individuals in organizations suggests that such behavior is a function of the characteristics of the focal moral problem—characteristics that are independent of the individual and the individual’s organization. His model differed from extant alternatives in that it explained that not all moral issues are processed the same, whereas previous models had assumed processing homogeneity. His analysis built upon existing, multi-step, stylized decision-making models. To that base of understanding he added several explicit influences of moral issue characteristics, labeling a collection of those characteristics the moral intensity of the issue. He summarized his insights in a model where the moral intensity of the idea-as-issue determined how it was processed in each of the four steps of decision making of individuals in an organization.

To be precise about that model, several definitions are helpful: Jones (1991) considered that a moral issue arises when the freely performed actions of a person could harm or benefit others (Velasquez and Rostankowski 1985), and that a moral agent is a person who makes a decision about a moral issue regardless of whether the agent recognizes that such an issue is involved. The three steps that occur after the recognition of the issue as a moral one involve the individual making a moral judgment (i.e., an assessment of the issue made by applying some level of critical deontological and teleological analysis and reasoning to determine what is morally correct), then establishing moral intent (i.e., the intension to act, or to not act, in a manner that is consistent with what is morally correct), and then engaging in moral behavior (i.e., planning and executing actions within the organizational context that are consistent, or not consistent, with what is morally correct). Jones based his main four-stage decision model on that of Rest (1986)—with modifications considered from Trevino (1986), Ferrell and Gresham (1985), Ferrell et al. (1989) and others. We adopt the model in our paralleling because it is a standard, built on decades of relevant work (Jones 1991), and is still in use today in various forms of information processing procedures (e.g., May et al. 2014; Schuler and Cording 2006).

The Jones (1991) Model involves explicitly tying the independent characteristics of the moral issue—collectively referred to as its moral intensity—to those four stages. Moral intensity is a construct capturing the extent of the issue’s moral imperative. Its dimensions are based on the law (e.g., on retribution—Packer 1968), and on moral philosophers’ considerations of proportionality (Garrett 1966; Wirtenberger 1962). It includes six dimensions of the moral issue: (i) the magnitude of consequences—a depth measure of the sum of the harms or benefits done to those impacted; (ii) the social consensus—a filter measure of the extent of social agreement in how the issue involves evil or good; (iii) the probability of effect—an expectation measure of the joint likelihood that the issue will be enacted and then will produce the harms or benefits anticipated; (iv) the temporal immediacy—a pace measure of delay between the present and the start of the issue’s consequences, where small delays imply greater immediacy; (v) the proximity—a familiarity measure of the psychological, social and physical nearness that the moral agent has for the people impacted by the issue; and (vi) the concentration of effect—a width measurement that is inversely proportional to the number of people affected by the issue. The impact of these dimensions on the decision-making process is taken as a whole.

Jones (1991) completes his theorizing by describing the impact of moral intensity through four propositions—one for each of the four stages in the process. He argues that ideas of high moral intensity, relative to those of low moral intensity, will likely: (i) be recognized as moral issues; (ii) prompt higher-level moral reasoning and cognitive moral development in their judgments; (iii) entail the establishing of moral intent; and (iv) entail the engaging of moral behavior by the agent. He also speaks to many other factors that could affect the phenomenon when he discusses possible extensions of the model as he recognizes the boundaries of his theory. One of the boundaries of Jones’s theory not discussed is the lack of consideration of the commercial opportunities related to the moral issues involved. We believe that business ideas entail an inextricable link between ethical and economic issues, a link that begins with every firm’s social contract (e.g., Carroll and Shabana 2010; Donaldson 2001).

3. Methods

What we describe below is a process model (Cornelissen 2017), built through analogy (Cornelissen and Durand 2014), paralleling an existing multi-step decision-making model, and paralleling how that model is affected by external sets of factors. Specifically, the methodology we use is theoretical extension—we extend the Jones (1991) Model of how ethical decision making is influenced by moral intensity to how entrepreneurial decision making is influenced by commercial intensity to how business decision making is influenced by both intensities together. Our analysis contributes to the understanding of opportunity assessment by defining commercial intensity in terms of economic proportionality, and by predicting its effect on the assessment process in isolation and when combined with the moral intensity dimension. Such an approach allows for a more complex analysis of the interdependencies possible between economic and ethical issues, extending beyond what has been modeled prior as independent, moderating or mediating interaction effects (e.g., Cannatelli et al. 2019; Valentine et al. 2011; Zhao and Lounsbury 2016).

In order to proceed in our analysis, we make several simplifying assumptions about the phenomenon. We describe the main ones here: First, we assume that the ideas underlying the opportunities are sufficiently formed and independent from the decision-maker such that their characteristics exist independently and accurately for individuals to access. This allows us to separate the idea existence phase from the idea assessment phase, avoiding the current challenges over how that existence originates (e.g., creation, discovery, both, or something else). That assumption (i.e., that the idea pre-exists and is separable from the individual judging it) is common in the opportunity assessment literature (e.g., Wood et al. 2014).3 Second, we assume that business activity, as part of human activity, is replete with voluntary options to assess and act upon ideas carrying moral and commercial weight. Third, we assume that the ideas are processed in the standard four-step manner described in the absorptive capacity and related information-processing literatures (Cohen and Levinthal 1990; Jones 1991; Venkataraman et al. 1997) where firms recognize the value of external information, assimilate it using judgment, transform it with intent and then apply it through behavior. Fourth, we assume that the decision-maker is influenced by the proportionality of the potential moral and commercial impacts of the idea to such a degree that it affects both her efforts and her opinions as she processes those ideas as actionable opportunities. Fifth, we assume that the decision-maker is boundedly rational and will combine related proportionality measures into one intensity measure per dimension (i.e., commercial or moral) when assessing the idea.

4. Results

This section describes the results of the theoretical extension. First, there are results from applying the Jones (1991) Model to economic issues that creates a commercial intensity construct. Second, there are results from analyzing the set of possible interactions between moral and commercial intensities.

4.1. Application of the Jones Model to Commercial Opportunities

It is important to understand that these two intensities characterize different things regardless of the parallels in analysis that we discuss below. Individuals in their organizations judge what is right and wrong with different scales, tools and social science than what is profitable or not. Regardless of any correlation and interaction of the two intensities, it is useful to separate them in order to study each, as is often done in reality (e.g., with the separation of law and ethics from commerce and economics).

That separation noted, we now argue close analytical and structural parallels between the Jones Model and our proposed model. The issues entail similar characteristics—both moral and commercial ideas are voluntary to consider, they affect others, they are multi-dimensional, they embody core parts of a firm’s social contract, they can each determine a firm’s fate and they constantly arise. Not all commercial opportunities are processed the same, even though the standard textbook approaches, and even most journal-based research prescriptions, implicitly take a rather homogeneous toolkit and instruction set to any given opportunity (e.g., Timmons and Spinelli 2009). Then, even when such a generic approach to entrepreneurship includes filters or stages that can alter which processing steps get done when, these approaches do not consider variance in how a step itself is done (e.g., how much effort is used in a particular process step). The Jones Model argues that the latter consideration is a main source of variance in processing ethical issues, and we follow suit regarding the processing of commercial ideas.

Paralleling Jones, to be precise about our model, several definitions are helpful: we consider that a commercial opportunity arises when the freely performed actions of a person (through her firm) could harm or benefit others in terms of providing new or improved products, services or organizations to address private needs in markets, and that a manager-as-entrepreneur is a person who makes a decision about a commercial opportunity (e.g., by enterprisingly exploiting it through her organization—Casson 1982). As before, the analysis is at the individual level of decision processing, where that individual is affected by and affects her firm and stakeholders in the community.

Our paralleling of the Jones Model involves identifying the commercial intensity dimensions and arguing the propositions over how they affect the entrepreneur’s behavior. We proceed through these requirements, referring back to the Jones Model as we do so, below. Note that the Jones Model combines two levels of analysis—individual and firm; individuals at the firm (e.g., the entrepreneur-manager) evaluate the opportunities within the context and constraints of their organization. They make decisions for their ventures, not for themselves. Our model retains this combined level of analysis perspective.

We define commercial intensity as the collection of independent characteristics of the commercial idea; specifically, it is a construct capturing the extent of the idea’s economic imperative. There are several sources from which to identify possible commercial intensity dimensions. To begin with, we consider the standard financial opportunity assessment criteria captured in entrepreneurship guidebooks and based on economic logic. Then, we revisit the Jones Model’s intensity dimensions for reference. Comprehensive entrepreneurship textbooks summarize the practical field knowledge about which dimensions of opportunities are the most important. For example, Timmons and Spinelli’s (2009) archetypal text suggests that the following characteristics are vital for identifying the more important and attractive commercial opportunities: market need and demand; market size, structure, growth rate, spread and capacity; production cost structure; benefits created for customers over the product life; investment returns and pace; capital requirements and cash flow; sustainability in terms of barriers to entry; harvest issues such as exit mechanisms; and fit with the venture team and context. These suggested dimensions cover both more and less than the Jones Model: the depth, width, pace and filtering dimensions are covered well, while those associated with expectation and familiarity are not; however, there are also new dimensions offered. The new dimensions include a competitive dimension given that there are private rather than public goods involved, and an explicit cost dimension concerning investment, returns, and cash flows.

Economic logic, especially at the micro level, is another solid source for commercial intensity dimensions to capture. In such logic we find the concept of expected value (i.e., in terms of assessing the impact of the opportunity as the sum of the products of the outcome state probabilities and the opportunity’s values in those states), which covers the expectation dimension in the Jones Model. From behavioral economics, we find the proximity heuristic used by boundedly rational decision-makers who over-weigh closer, more available experiences in their choices and assessments (e.g., Holcomb et al. 2009), which covers the proximity dimension in the Jones Model.

Thus, we find that the dimensions of moral ideas-as-issues that contribute to its intensity are similar to the dimensions relevant to commercial opportunities-as-ideas especially regarding proportionality; proportionality embodying the expected impact on others of a potential occurrence of the focal ethical or commercial issue. We revisit the Jones Model intensity dimensions now to solidify that similarity to our proposed dimensions for commercial intensity:

Magnitude (in depth, width, length) is also a dimension of commercial intensity, and is also based on the logics of human behavior and economic rationality, supported by studies that reveal higher industry entry rates when larger perceived prizes are present (e.g., Delacroix and Carroll 1983). Social Consensus is defined more broadly for commercial opportunities than for morality. We use consensus to capture the certainty of consumer demand, of technological feasibility and of regulatory acceptance. Essentially, it signifies others also believe that the opportunity is commercially viable. This has logical support (e.g., one cannot judge the opportunity without having confidence in the acceptability of the opportunity to the consumer, to the laws of physics, and to the regulators) as well as empirical support (e.g., there is more R&D investment directed at popular grand challenges where there exists a high consensus that unmet needs are addressable through viable technologies—e.g., Chen 2008; Norberg-Bohm 2000). Probability of Effect is based on the concept of expected value, and is especially appropriate given that new commercial opportunities are so often characterized by the high levels of risk and other uncertainties underlying expectations (e.g., Keyes 1985). Temporal Immediacy is the length of time between now and onset of the consequences of the economic act, and is based on the economic rationality of discounting the future because time delays decrease the probability of an outcome’s occurrence as it allows more interventions to occur (e.g., payback periods—Lefley 1996). Proximity is the feeling of nearness that the agent has for those impacted and arises here when a decision-maker exploits, and gets feedback from, consumers and partners who are nearer to her, or even when she pursues a commercial opportunity that is closer to her own personal mission. We see this effect in several ways: One of the main reasons people become entrepreneurs is their feeling of closeness to an unmet consumer need and its solution (Kawasaki 2004). One of the main ways entrepreneurs begin their commercial venturing is by starting locally to build legitimacy and buzz with those socially, culturally, psychologically and physically near them (e.g., Facebook’s origins at Harvard, then other Boston universities, and then other Ivy Schools and so on—Philips 2007). Concentration of Effect is an inverse function of number of people affected by an act of a given magnitude (Jones 1991), and is related to the commercialization of the opportunity in terms of the distribution underlying the demand curve and the bargaining power of industry players relative to the focal organization (Porter 1980).

To these dimensions we add profitability-related characteristics for the commercial intensity construct (although Magnitude and Probability of Effect are also arguably profit-related). Because opportunity issues tend to involve private rather than public goods, several new concerns arise, including those related to costs, appropriability and competition. The pursuit of commercial opportunities is voluntary and so will only be rationally conducted when there exists an expected return exceeding the costs, making the initial and ongoing costs important to consider, as well as the returns in terms of the benefits created that are appropriated. Then, given the possibility of profitable activities, competition should also be a consideration in understanding whether an opportunity for the decision-maker and her organization exists.

Costliness refers to the initial and ongoing expenses expected for addressing the opportunity. We include costs because they relate to the rational cost–benefit analysis that people conduct when making decisions to pursue new activities. Empirically, we know that costs affect the pursuit of opportunities because these are often considered one barrier to entry for new ventures (Porter 1980). While the Proximity dimension may affect some of these costs indirectly (e.g., in terms of the easing of efforts needed for legitimization, resource access and other possible cluster effects—Zhang and Li 2010), it is worthwhile to explicitly delineate the direct costs with a separate dimension. In terms of the intensity, the lower the costliness, the higher the commercial intensity.

Appropriability refers to how much of the value created by addressing the opportunity the entrepreneur’s organization captures, value it could use to cover its costs and reward its investors. It is a function of several factors, including the relevant intellectual property protection regime. We include appropriability for rationality reasons because, for entrepreneurs to voluntarily choose to pursue an opportunity, they need to know if their private costs are covered by the proportion of benefits they privately receive. Empirically, we know that such rationality is supported, for example, by investments in protection of intellectual property (e.g., Mann and Sager 2007). While the Concentration of Effect dimension may relate to the bargaining power aspect of value appropriation, bargaining power in the value chain has more ingredients than simply the number of affected parties or the size of the purchase to them (Porter 1980); appropriability provides a more complete and direct measure of returns available to the entrepreneurs pursuing the opportunity. The higher the appropriability, the greater the commercial intensity.

Competition refers to extent of rivalry awaiting those entrepreneurs pursuing the opportunity. It summarizes the effects of industry structure and possible positioning within that structure. It is included for logical and empirical reasons. Logically, the value created by pursuing the opportunity is limited by substitute offerings that also address the need underlying the opportunity; thus, rational entrepreneurs will pursue opportunities with less competition (e.g., with fewer and weaker rivals and substitutes, with more differentiation options, and that are more novel—Williams and Wood 2015), ceteris paribus. Empirically, we know that new venture entry rates are higher when a new market opens up where competitive supplier pressures are relieved by expected growth in demand (e.g., Lilien and Yoon 1990). The lower the competition, the higher the commercial intensity.

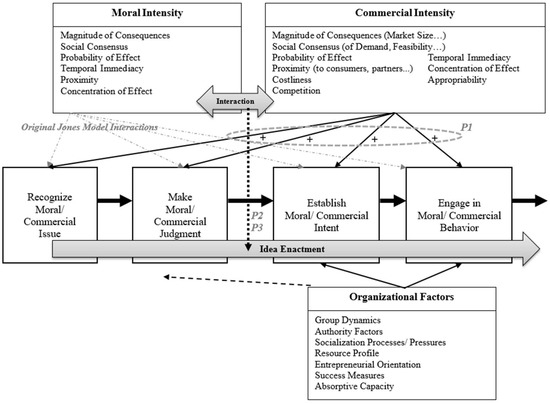

We assume that the boundedly rational decision-maker will consider all of these dimensions as a whole in one intensity construct. Essentially, the decision-maker recognizes, judges and consolidates the information represented by the dimensions internally into our single commercial intensity value. Figure 1 depicts both the original Jones Model and our parallel model together so the similarities, differences and interactions can be visualized. We describe those interactions and argue the propositions (indicated by the P’s in the figure) below.

Figure 1.

The Jones (1991) Model Paralleled for Commercial Intensity.

This completes our parallel definition of the commercial intensity. The intensities are similar, with a few new dimensions added in order to account for the extra concerns that suppliers of private goods have over those of public goods. We stay consistent with Jones (1991) as well on the assumption that an intensity is best considered holistically for the purpose of exposition—in order to provide a clear explanation of why not all moral or commercial opportunity ideas are processed the same. The assumption is also consistent with the bounded-rationality model of the decision-maker (e.g., it is easier for the decision-maker to deal with one or two big effects than dozens of effect-dimensions that may be related in complex ways).

We model a four-stage decision-making process: In the first stage, the entrepreneurial manager recognizes the offered idea as a commercial opportunity; that is, as an idea that she can voluntarily act upon. In the second stage, a commercial analysis judgment is made by applying filters, heuristics and methods of varied complexity in order to determine whether the idea is economically attractive to her organization. In the third stage, the intent to pursue (or not pursue) commercialization is established accounting for her perceptions of the organizational factors. In the fourth stage, there is engagement in commercial behavior, where she acts on the intentions to pursue the commercial opportunity (or not), under the realities (e.g., the constraints, obstructions and supports) of the circumstances. This is an established model of a process that starts at the micro-level and ends at the meso-level. The explicit modeling of the latter is exclusively in terms of the organizational factors’ effects on the process, mostly considered as constraints (e.g., in terms of precedents, identity, or resource restrictions).

We now argue our composite parallel propositions relating the commercial intensity to likely entrepreneurial behavior in exploiting the opportunity. We step through the individual decision process as we do so.

We first argue that intensity will increase the likelihood of recognition by the individual. Intensity affects important aspects of an individual’s attention, specifically salience (i.e., standing out from the background) and vividness (i.e., being emotionally interesting, imagery-provoking and proximate) (Jones 1991). Higher salience and vividness of the issue’s possible consequences for others makes that idea more likely to be recognized as a moral issue in Jones’s model. Higher intensity increases salience as more extreme effects, more concentrated effects, and more proximate effects all help the issue stand out. We expect that the same arguments apply to the recognition of economic opportunities. Higher intensity increases vividness as issue magnitude, concentration, consensus, probability and proximity all make it more emotionally interesting. We expect that the same arguments apply to the recognition of economic opportunities. Besides being considered as economic in nature, the idea must also be considered as voluntary to meet the full definition of the types of ideas we focus on here. Jones (1991) argued that freedom of choice is associated with the availability of good options, which is a function of magnitude and social consensus. We expect that the volition for economic opportunity ideas is also a function of its intensity dimensions (e.g., as more options would be available with higher consensus in technological feasibility, with less competition, with more forgiving cost structures and so on).

The judgment stage involves the choice and application of a method for analyzing the idea, where such methods vary in complexity and effort (Kohlberg 1976). This choice is intensity-dependent as based on intuitive, theoretical and empirical supports. Intuitively, judgment takes effort and so individuals will economize when the stakes are lower—when the magnitude, probability of effect, concentration and proximity are lower. Theoretically, higher possible effects and returns justify higher investments of costly efforts in doing a deeper and wider assessment of ideas (e.g., Fiske and Taylor 1984). Empirically, studies have indicated that higher judgment efforts are used over issues with greater moral intensity (e.g., Taylor 1975; Weber 1990). These supports apply to commercial intensity as affecting the application of more complex opportunity assessments. For example, opportunities with higher intensities in terms of their magnitudes of market potential appear to demand more thorough and complex analyses by the decision-maker (e.g., Ge et al. 2005; Hoenig and Henkel 2015).

The post-judgment decision over what to do now defines the establishment of intent. Once the judgment over the issue is made, the decision-maker needs to balance the intensity against other factors, including those at the organizational level. Such a balance may not result in an intension that is consistent with the judgment (aka a positive intent). Jones (1991) argues that intensity increases the positive intent for several reasons: proximity increases the feeling of responsibility; social consensus increases the desirability for positive intent; and vividness and salience increase the emotional draw to do the right thing. The same mechanisms should be at play for commercial intensity. We expect that ideas with high magnitude, consensus, proximity, appropriability and probability of effect, and with low costs and competition, to result in positive intent (i.e., where the decision-maker intends to pursue an opportunity judged attractive). Economic rationality suggests so, as do studies correlating the perceived attractiveness of an opportunity to entrepreneurial intent (e.g., Teplov et al. 2016; Wood et al. 2014).

The planning and implementing of actions consistent with judgments and in light of possible impediments characterizes positive behavior. Intensity increases the likelihood of behaviors that are aligned with positive intentions (Jones 1991). We argue that an individual will act on a judgment that an attractive opportunity exists by planning and committing resources to exploit that opportunity. Greater proximity to partners and consumers will increase a feeling of responsibility to address the opportunity’s underlying market need. A greater magnitude and probability and consensus of the effect, especially when costs and competition are lower and appropriability is higher, will likely increase the likelihood of efforts to exploit the opportunity with positive actions. Empirically, studies have indicated that entrepreneurial action increases with opportunity-as-idea’s attractiveness (e.g., Dimov 2010; McKelvie et al. 2011). Thus, we propose:

Proposition 1.

Entrepreneurial behavior leading to the enacting of commercial opportunities will be observed more frequently for opportunities of high commercial intensity than of low commercial intensity. Specifically, high commercial intensity will increase: (a) the recognition of commercial opportunity; (b) the application of more sophisticated economic analysis; (c) the intent to commercialize; and (d) the commercialization activity.

We argue that the process will be moderated, especially in the later stages, by organizational factors. For commercial issues, it is important to consider the effects of salient organizational factors, such as the firm’s: resource profile (because we expect constraints in staff, equipment and finances when enacting); entrepreneurial orientation (because we expect the organization’s aggressiveness will affect the possible enactment—Lumpkin and Dess 1996); success measures (because we expect these to be a basis for trade-offs across ideas—Bryant 2007); and absorptive capacity (because we expect expertise to have an effect on the processing of ideas—Cohen and Levinthal 1990; Jansen et al. 2005). We leave the exact nature of the moderating effects for future work in order to focus on the analysis of the interactions of the two intensities that are now defined.

4.2. When Intensity Models Interact

Decision-makers often face opportunities characterized by moral issues, commercial implications, or both. They voluntarily confront ideas that have the potential to positively or negatively affect others in ways both financial and non-financial. This is part of every organization’s social contract, as each organization needs to act as a responsible social agent in fulfilling the expectations of its various stakeholders to create value with at least minimum levels of financial returns and ethical behaviors. It is not uncommon for decision-makers to face opportunities entailing both moral and commercialization-related significance. Research in social entrepreneurship (e.g., Hockerts 2006) and in crisis management have begun to describe and analyze such decisions, but from much more focused circumstances (e.g., in the latter, when the organization faces an existential threat). Regardless, a gap remains in formal theory for addressing the more general cases of decision making in organizations over ideas with both moral and commercial significance in a comprehensive, structured and process-based manner (e.g., Basu and Palazzo 2008; Donaldson and Dunfee 1994; Strong and Meyer 1992).

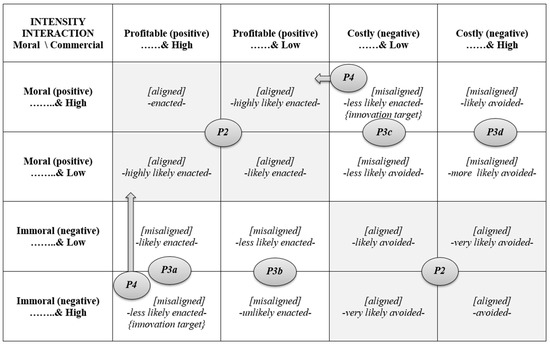

In order to properly address the interaction of the two separate intensities, we need to consider two aspects of each of those intensities—its level (i.e., high or low) and its judgment of the opportunity (i.e., positive or negative). This implies sixteen possible combinations under even the simplest characterization. Each intensity has high and low levels relating to positive or negative judgements of the opportunity, giving four basic possible states of each intensity (i.e., high-positive, low-positive, low-negative, and high-negative). Each of an intensity’s four states can then be combined with one of the other intensity’s four states. Figure 2 depicts these interactions and identifies what the propositions in this section relate to. That noted, there are ways to address the large number of combinations that reduces the complexity of analysis involved. One way is to note that the pairs are either aligned on the judgments or not. That alignment occurs when the idea is judged as moral and commercially attractive (i.e., has positive alignment), or when the idea is judged as immoral and commercially unattractive (i.e., has negative alignment). The collection of aligned combinations constitutes half of the sixteen cases; we label these cases the first type of interaction between the two intensities.

Figure 2.

The Combinations of Intensity Interactions with Corresponding Propositions.

When the alignment is positive, the entrepreneur-as-decision-maker and her organization have the incentive to act. The opportunity is most likely to be enacted (i.e., commercialized in a moral, socially beneficial manner) when the intensity levels are both high, less so when only one is high, and much less so when both are low. The likelihood of enactment is explained by the stakes involved. In this case, doing good is doing well and being ethical makes money. This can occur when waste reduction also is cost reduction (Porter and Van der Linde 1995), or when the socially responsible action can be leveraged to differentiate a product (e.g., the Body Shop in cruelty-free cosmetics; Bombas in socks and apparel; Starbucks in ethical sourcing), or when an efficiency improvement not only saves money but reduces pollution (e.g., Walmart’s investment in solar and high-efficiency lighting), or when a new supplier is not only cheaper but also employs a disadvantaged group (e.g., Greyston Bakery), or when an application of the opportunity’s new technology helps the environment or the community (e.g., smart grids and smart meters; reduced packaging; the use of recycled materials; Zhangzidao Fishery Group’s integrated multitrophic aquaculture farming method; Shree Cement’s intelligent energy heat-capturing process; Natura’s use of sugarcane-based plastic), or when some proceeds are diverted to charity (e.g., Bixby; Roma; Soapbox; Warby Parker). When the market logic is reinforced by the social logics (e.g., in legitimacy, in values, in culture) then decision-makers (and their organizations) are more likely to follow its direction (Zhao and Lounsbury 2016), so if the opportunity is expected to make a profit and satisfy the community, then it is more likely to be enacted. When the commercial desirability of the opportunity is matched with feasibility-as-social-support, then the likelihood of entrepreneurial action increases (McMullen and Shepherd 2006; Patzelt and Shepherd 2011). By contrast, when the alignment is negative then the entrepreneur-as-decision-maker and her organization have the incentive to not act (e.g., as both the social and economic returns are unattractive). Decision-makers and their organizations rationally avoid self-harm that could occur through expected financial or social losses, and so will oppose enacting any opportunities that involve such harms, and more so the greater the expected harms. Thus, we propose:

Proposition 2.

When an opportunity’s moral and commercial intensities are aligned and positive (negative), then the higher the intensity levels, the more likely the opportunity will (not) be enacted.

The second type of interaction occurs when judgments are misaligned—when the opportunity is judged as moral yet commercially unattractive, or when it is judged as immoral yet commercially attractive. To streamline the analysis here, we will focus on for-profit organizations—where we assume that economic concerns will outweigh ethical ones. More specifically, the following asymmetry in the interaction of the two intensities is assumed to exist: ways to make money are not often restricted by ethics (although they may be restricted by law), whereas ways to be ethical are often restricted by economic, technological and even legal feasibility (e.g., giving all profits away to charity likely violates a CEO’s fiduciary responsibilities to the shareholders). This asymmetry and the main (economic) goal assumed for the organization provide a way to prioritize the influence of any opportunity’s two intensities on whether it will be enacted. In short, based on the logic of the model and on economic rationality (e.g., attempted utility maximization—Simon 1979), we expect that ideas with commercial intensities that are both high and positive to be more likely enacted, with the effect of negative moral intensity reducing that likelihood the higher its level. This expectation is consistent with work that finds social logics moderating the influence of market logics (e.g., Zhao and Lounsbury 2016) or acting as an independent, sometimes countering, influence (e.g., Cannatelli et al. 2019).

As to the existence of this kind of misaligned venture (and constituting four of the sixteen combinations), there are many examples of profitable but socially harmful new businesses: there are opportunities in the sharing economy that can cause harm when regulation is slow to respond with applicable safety rules (e.g., Uber; Napster); there are opportunities that provide market power that harms consumers (e.g., Turing Pharmaceuticals); there are opportunities that exploit addictions (e.g., gambling; alcohol); and there are opportunities that exploit low-cost scaling to harm the naïve (e.g., phishing scams; pyramid schemes). Stylized facts are also supportive of the claim, such as that a firm in financial exigency (e.g., facing bankruptcy) will most often cut corners, oftentimes in a manner that endangers its workers and the environment, in order to make sufficient revenues to survive.

The other kind of misaligned venture exists when the moral intensity is positive but the commercial intensity is negative (which constitutes the last four of the sixteen combinations). A consistent pattern is expected if the opportunity is taken as is. In that case, the negative commercial intensity will outweigh any positive moral intensity, with that weight growing in level of commercial, and reducing in level of moral, intensity. For-profit ventures (and their paid decision-making employees) simply cannot survive by taking on money-losing projects, regardless of how socially popular they are (e.g., giving away free stuff was the road to bankruptcy for many Internet firms of the late 1990s—Kaplan 2002). Thus, we propose:

Proposition 3a.

When intensities are misaligned, opportunities with commercial intensities that are both high and positive are more likely to be enacted, with the effect of negative moral intensity reducing that likelihood the higher its level.

Proposition 3b.

When intensities are misaligned, opportunities with commercial intensities that are both low and positive are relatively less likely to be enacted, with the effect of negative moral intensity reducing that likelihood the higher its level.

Proposition 3c.

When intensities are misaligned, opportunities with commercial intensities that are both low and negative are likely to be avoided, but with the effect of positive moral intensity decreasing that likelihood the higher its level.

Proposition 3d.

When intensities are misaligned, opportunities with commercial intensities that are both high and negative are extremely likely to be avoided, with the effect of positive moral intensity decreasing that likelihood the higher its level.

A third type of interaction may occur within a subset of the second type, for some of the misaligned cases, as observation has revealed. In some misaligned cases, where moral intensity is negative and are high, the decision-maker may form an intent to not take the opportunity as is, but instead to address that inefficiency as part of her behavior and acting through her firm. Stylized facts indicate that entrepreneurial decision-makers do not always take an opportunity as is, but instead try to shape it to their advantage (e.g., Dimov 2007). In two of the sixteen cases, it is more likely to see savvy and caring entrepreneurs not taking the opportunity as is but instead extending their judgment phase to see what if the opportunity can produce more value commercially and socially, and likely where rivals won’t.

The first case is characterized by high positive moral intensity and low negative commercial intensity. The added innovative intent is to shape the commercial intensity to be more attractive to enact by reducing the costs and/or increasing the value appropriation. Then, at least the latter seems possible, given that significant value is being created as indicated by the high moral intensity which should be appropriable at even a low level (e.g., through a market-based business model—e.g., Battilana and Dorado 2010).4 The motivation to innovate appears especially high in this case when the decision-maker’s firm desires a positive brand image or feels social pressures due to its embeddedness (e.g., Dey and Steyaert 2016).

The second case is characterized by a high negative moral intensity combined with a high positive commercial intensity. Here, the trade-off between intensities appears to be greedy, antisocial and myopic; in that case, the entrepreneur-as-decision-maker is likely motivated to either find a cost-effective way to reduce the social harms or to increase the social benefits. Given funds are available—as the commercial intensity is positive—these could be used to creatively work with the potential victims to move them out of harm’s way, compensate them or give them more control. Alternatively, very ethical firms may find new ways of accounting for social harms in the commercial intensity assessments at the firm level (e.g., Unerman et al. 2018) or, at a larger scale, through lobbying in ways that help align the moral and commercial intensities (e.g., to creatively self-regulate in order to mitigate the expected high harms and to protect under-voiced victims like the environment—e.g., Maxwell et al. 2000).

This third type of interaction is more complex and arises because the two intensities are not simply modeled as independent, moderating or mediating in nature. It speaks to the kind of tensions that can be resolved by new venture ideas (Davidsson 2015) when the goals are clear (i.e., finding alignment when intensities are misaligned) and the means exist (e.g., uncaptured value; reducible costs; available funds to compensate victims) but were not initially given. Thus, we propose:

Proposition 4.

When enacted, opportunities that are initially judged as high positive moral intensity with low negative commercial intensity (or as high positive commercial intensity with high negative moral intensity) are more likely to have been modified through innovation to have a more positive commercial (less negative moral) intensity.

5. Discussion

We have described a partial theory that explains the why and the how of opportunity assessment when both economic and ethical issues are involved using standard theory-building pieces outlined in Dubin (1969).5 We did so because decisions combining commercial and moral intensities are important to a wide range of decision-makers involved in business and society (Fiet 2007). We chose to model the interactions between these intensities as interdependently complex rather than as independent, mediating or moderating in nature because the existing literature supports that complexity (e.g., Baron and Ensley 2006; Battilana and Dorado 2010; McMahon and Harvey 2007; Porter and Kramer 2006; Yunus 2006).

Our introduction of the commercial intensity and our explanation of its connection to the moral intensity are contributions. Our analysis complements the literatures on phenomena where the economic and ethical logics at a firm need to be carefully managed, such as with social entrepreneurship and in hybrid firms. Our analysis suggests that opportunities need to be assessed holistically in order to make the best decisions on whether to pursue them and how. Further, our analysis indicates that the full process of assessment should be modeled, rather than just the judgment stage, in order better understand why not all opportunities are even identified or initiated for action in the same way. Our analysis also extends the impact of the moral intensity stream by paralleling it and describing how its similar dimensions can affect the commercial intensity assessments of opportunities. Additionally, we present a comprehensive sixteen-case exploration of the main interactions among intensities—where the current papers in the related literatures like social entrepreneurship do not—highlighting where making implicit assumptions over interactions could go wrong as well as what the paths are for making efforts towards improved outcomes.

Besides the preceding academic implications, our detailed paralleling of the Jones Model that adds a new type of intensity to the opportunity assessment process provides a ready template for adding further potential intensities involving familial, spiritual and political assessments over issues and opportunities.

In terms of implications for management, our process model provides a new and practical benchmark. Such a benchmark can be used for diagnosing potential causes of Type I and Type II errors; when a bad opportunity is enacted (e.g., one with negative commercial or highly negative moral intensity) or when a good opportunity (e.g., one with positive commercial and moral intensities) is missed, our framework may help identify why. Our model identifies steps and factors to divide and conquer the complexity of the full opportunity assessment process so that managers can more easily identify where and when the system can go wrong and figure out how to address the what, why and who involved.

Additionally, the interdependence modeled in the interactions of the intensities in our model helps identify where innovative activities should be targeted for those firms interested in being more socially responsible.6 The model identifies the likely overlaps in the intensity dimensions to leverage, as well as the sources of value what could be transferred through the innovation in order to better align the intensities (see Proposition 4). We leave precise prescriptions—which are likely to require modifications for idiosyncratic organizational characteristics—for future work.7

5.1. Limitations

Every theoretical model makes assumptions worth discussing, and this model is no different.

Consider four such assumptions: First is the assumption that a competent focal agent exists with the abilities and resources to affect others. This is a strong, simplifying, and necessary assumption to focus the model, but it leaves open a larger question of how issues—commercial and moral—are distributed to those individuals-within-organizations who can act upon them, to at least some potentially significant effect, and whether that distribution is efficient.

Second is the assumption that commercial-opportunities-and-moral-problems simply appear at a reasonable rate; this without any story of their origins or of how previous actions by the decision-maker or others affect that rate. Further, the assumption is that these issues appear when they are in a pliable state—when they can be significantly affected by the behavior of the decision-maker. It may be useful to consider what occurs outside that timing window—in terms of how opportunities at different stages of their lifecycle are processed—and how the constraints defined by those pliable parts affect behaviors.

Third is the assumption stated by Jones (1991) that there exists some stability in each cycle of the process for the issue, for the decision-maker and for the context. It may be useful to explore alternatives in the form of realistic shocks to the system, such as updated firm constraints.

Fourth is the assumption that the information about the idea is accurate, objective and freely available to the organization. It is an assumption about the ease and quality of forethought and so entails a boundary condition on the applicability of the model based on the level of confidence that the decision-maker has in assigning the intensity scores. Breaking this assumption leads into adding issues about the idea’s origination process, such as the cost of discovering the idea and its intensity information, or the possible sunk costs that may arise if the idea-as-opportunity was created by someone who can influence the assessment process. This integration of the two processes—each process entailing its own substantial complexity—is left for future work.

5.2. Future Work

Future work could consider extending the model in ways that may alter the original assumptions as we have suggested directly above, but should begin by testing the main propositions. Testing our model’s propositions could be attempted both in the field and in the lab. We expect the measures for such primary data-centric work to be based on verbal constructs, some of which may have to be newly built (but could be based on dimensions and definitions for the commercial and moral intensities provided). For specifically testing the interaction propositions, we expect that lab and survey-based work, using marketing-like, conjoint-style analysis (e.g., based on constructed trade-off scenarios) to be most applicable.

Future work may also consider adding more dynamics to the model, dynamics that would lead to new propositions (acknowledging that adding additional intensities or dynamics increases the possibility that the model becomes overly complex). For example, one could propose a set of meta-relationships that describe how the decision-making process develops over the lifespan of a specific opportunity as its intensities evolve, or as the organization itself evolves given feedback on its successes, failures and social contract expectations. Such relationships would be new to variants of the Jones Model given morality is more stable and backwards-looking (e.g., for precedent) while commercial potential is less stable, constantly updated and forwards-looking (e.g., for arbitrage), and so would be more likely to evolve its processing in interesting ways. For example, we would expect feedback on the successes and failures of opportunities pursued and foregone to affect the weightings given to the commercial intensity dimensions, to the judgment methods applied, and to any inconsistencies among stages that led to any suboptimal outcomes (e.g., where intent was proved right but action was blocked).

We would also like to see future work that extends the partial theory to further dimensions of ideas along the same lines as we have provided for economic impact (e.g., for the dimension of familial intensity for family businesses), first by describing the new intensity alone and then by describing how it interacts with other intensities. Regardless of the particular paths taken, however, we believe that exploring an intensity-focused approach to opportunity assessment is valuable for increasing our understanding of the drivers and impacts of strategic managerial and entrepreneurial activities that have significant and multi-dimensional effects on society.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Jones (1991) defines moral intensity as a construct capturing the extent of the issue’s moral imperative, with dimensions based on the law and on moral philosophers’ considerations of proportionality (with proportionality measuring items like the magnitude and proximity of impact). We define commercial intensity similarly—as the collection of independent characteristics of the commercial idea forming a construct capturing the extent of the idea’s economic imperative (based on the economic and strategic proportionality—as measured by potential effects on profitability, competitiveness, market size and so on). |

| 2 | We complement the work in hybrid firms by newly explaining how firms can seek to blend value on a opportunity-by-opportunity basis rather than attempting to do good by adhering to a mission (McMullen and Warnick 2016) or by selectively combining logics (Pache and Santos 2013) or by creating a common identity (Battilana and Dorado 2010). We complement the social opportunity discovery research by adding knowledge about action-formation mechanisms on the meso-level (with intensities as moderators) and by describing a process for identifying opportunities for social benefit where calls for insight exist (Austin et al. 2006; Saebi et al. 2019). We do so using our novel intensity construct (that differs from existing ones like Vogel’s (2017) venture idea that ignores proportionality characteristics). |

| 3 | This is not to suggest that the initial, given characteristics of the ideas cannot be modified when enacted by any specific venture. Every idea is open to some modification through innovation efforts. |

| 4 | The revenue part of the commercial opportunity is technically sound (e.g., the product or service works) but the cost of transacting (e.g., producing, delivering, contracting, or monitoring) can remain too high for a target application. There, we expect serious innovative efforts to find a way to address the specific source of commercial unattractiveness with some type of technological, cultural or process invention that makes the enactment economically viable (e.g., the peer-monitoring of micro-finance; the middleman elimination of blockchain e-currencies; the exploiting of the economics of scale of social interaction by reaching the bottom of the pyramid in distribution—Vachani and Smith 2008). More innovation should occur when the potential societal returns are higher in intensity, and when the moral issues are more proximate to the entrepreneur-as-decision-maker (e.g., for people like Yunus, Gates and others). |

| 5 | The theory’s units are the moral and commercial intensities, the decision processing steps and the organizational factors. The theory’s system containing those units is the organization’s process of dealing with ideas of varying moral and commercial intensities. There are identifiable system states; these bracket each step of the process. The system is bounded by the collection of steps—the phenomenon explained begins with input into the system when an awareness of the opportunity can occur and ends with the entrepreneurial manager’s behavior. The laws of interaction among the units in the bounded system, per state, relate to the influence of the intensities and organizational factors on the processing steps. The resulting propositions are argued in the main body of the paper. |

| 6 | Such innovative activities may be directed or complemented by crowdsourcing, especially when such sourcing can access a wide range of stakeholders who can advocate and exploit different dimensions of the moral and the commercial intensities involved when proposing potential new fixes, modifications, tools and solutions. |

| 7 | Our analysis provides a new model that can change the current way opportunities are processed. They should be analyzed holistically across their various intensities rather than in isolation because otherwise interdependencies will be missed. They should be analyzed across the four steps of processing and not just in the judgment stage because otherwise their likelihood of enactment will not be understood. They should be understood within a comprehensive map of the possible intensity interactions in order to visualize the path required for improvement. Their assessment should be understood within a set of explicit assumptions about the modeling of the process, because otherwise the limitations will not be known. Moreover, their intensity dimensions should be known in order to leverage any commonalties across such intensities. We hesitate to provide a simple algorithm for this modified process, given the idiosyncratic natures of the firm, its context and the ideas-underlying-the-opportunities involved. The benefit from applying our changes is better decision making about opportunities (based on the fuller understanding of the intensities involved and their interaction). The cost is the additional effort in making those changes (and making the measures and analyses more explicit). |

References

- Austin, James, Howard Stevenson, and Jane Wei-Skillern. 2006. Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different, or Both? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 30: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baron, Robert A., and Michael D. Ensley. 2006. Opportunity recognition as the detection of meaningful patterns: Evidence from comparisons of novice and experienced entrepreneurs. Management Science 52: 1331–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Basu, Kunal, and Guido Palazzo. 2008. Corporate social responsibility: A process model of sensemaking. Academy of Management Review 33: 122–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Battilana, Julie, and Silvia Dorado. 2010. Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal 53: 1419–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bryant, Peter. 2007. Self-regulation and decision heuristics in entrepreneurial opportunity evaluation and exploitation. Management Decision 45: 732–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannatelli, Benedetto Lorenzo, Brett Richard Smith, and Alisa Sydow. 2019. Entrepreneurship in the controversial economy: Toward a research agenda. Journal of Business Ethics 155: 837–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Archie B., and Kareem M. Shabana. 2010. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. International Journal of Management Reviews 12: 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casson, Mark. 1982. The Entrepreneur: An Economic Theory. Totowa: Barnes & Noble Books. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Hsinchun. 2008. Mapping Nanotechnology Innovations and Knowledge: Global and Longitudinal Patent and Literature Analysis. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer Science & Business Media, vol. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Wesley M., and Daniel A. Levinthal. 1990. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly 35: 128–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, Joep P., and Rodolphe Durand. 2014. Moving forward: Developing theoretical contributions in management studies. Journal of Management Studies 51: 995–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, Joep. 2017. Editors Comments: Developing Propositions, a Process Model, or a Typology? Addressing the Challenges of Writing Theory Without a Boilerplate. Academy of Management Review 42: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davidsson, Per. 2015. Entrepreneurial opportunities and the entrepreneurship nexus: A re-conceptualization. Journal of Business Venturing 30: 674–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Delacroix, Jacques, and Glenn R. Carroll. 1983. Organizational foundings: An ecological study of the newspaper industries of Argentina and Ireland. Administrative Science Quarterly 28: 274–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, Pascal, and Chris Steyaert. 2016. Rethinking the space of ethics in social entrepreneurship: Power, subjectivity, and practices of freedom. Journal of Business Ethics 133: 627–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimov, Dimo. 2007. Beyond the single-person, single-insight attribution in understanding entrepreneurial opportunities. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 31: 713–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimov, Dimo. 2010. Nascent entrepreneurs and venture emergence: Opportunity confidence, human capital, and early planning. Journal of Management Studies 47: 1123–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, Thomas, and Lee E. Preston. 1995. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of Management Review 20: 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, Thomas, and Thomas W. Dunfee. 1994. Toward a unified conception of business ethics: Integrative social contracts theory. Academy of Management Review 19: 252–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, Thomas. 2001. Constructing a social contract for business. Business Ethics: Critical Perspectives on Business and Management 1: 209–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dubin, Robert. 1969. Theory Building. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- El Ebrashi, Raghda. 2013. Social entrepreneurship theory and sustainable social impact. Social Responsibility Journal 9: 188–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, Odies C., and Larry G. Gresham. 1985. A contingency framework for understanding ethical decision making in marketing. Journal of Marketing 49: 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, Odies C, Larry G. Gresham, and John Fraedrich. 1989. A synthesis of ethical decision models for marketing. Journal of Macromarketing 9: 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiet, James O. 2007. A prescriptive analysis of search and discovery. Journal of Management Studies 44: 592–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, Susan T., and Shelley E. Taylor. 1984. Social Cognition. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, Thomas M. 1966. Business Ethics. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, D., James M. Mahoney, and Joseph T. Mahoney. 2005. New Venture Valuation by Venture Capitalists: An Integrative Approach. Working Paper. Champaign: University of Illinois at Urban Champaign, pp. 5–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gruber, Marc, Sung Min Kim, and Jan Brinckmann. 2015. What is an attractive business opportunity? An empirical study of opportunity evaluation decisions by technologists, managers, and entrepreneurs. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 9: 205–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynie, J. Michael, Dean A. Shepherd, and Jeffery S. McMullen. 2009. An opportunity for me? The role of resources in opportunity evaluation decisions. Journal of Management Studies 46: 337–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockerts, Kai. 2006. Entrepreneurial opportunity in social purpose business ventures. In Social Entrepreneurship. Edited by Johanna Mair, Jeffrey Robinson and Kai Hockerts. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hoenig, Daniel, and Joachim Henkel. 2015. Quality signals? The role of patents, alliances, and team experience in venture capital financing. Research Policy 44: 1049–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, Tim R., R. Duane Ireland, R. Michael Holmes Jr., and Michael A. Hitt. 2009. Architecture of entrepreneurial learning: Exploring the link among heuristics, knowledge, and action. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 33: 167–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, Justin J. P., Frans A. J. Van Den Bosch, and Henk W. Volberda. 2005. Managing potential and realized absorptive capacity: How do organizational antecedents matter? Academy of Management Journal 48: 999–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, Thomas M. 1991. Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review 16: 366–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Philip J. 2002. F’d Companies: Spectacular Dot-Com Flameouts. New York: Simon & Shuster. [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki, Guy. 2004. The Art of the Start: The Time-Tested, Battle-Hardened Guide for Anyone Starting Anything. New York: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, Ralph. 1985. Chancing It. Boston: Little, Brown. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg, Lawrence. 1976. Moral stages and moralization: The cognitive-development approach. In Moral Development and Behavior: Theory, Research and Social Issues. Edited by Thomas Lickona. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, pp. 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lefley, Frank. 1996. The payback method of investment appraisal: A review and synthesis. International Journal of Production Economics 44: 207–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilien, Gary L., and Eunsang Yoon. 1990. The timing of competitive market entry: An exploratory study of new industrial products. Management Science 36: 568–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lumpkin, G. Tom, and Gregory G. Dess. 1996. Clarifying the Entrepreneurial Orientation Construct and Linking it to Performance. Academy of Management Review 21: 135–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, Ronald J., and Thomas W. Sager. 2007. Patents, venture capital, and software start-ups. Research Policy 36: 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maxwell, John W., Thomas P. Lyon, and Steven C. 2000. Self-regulation and social welfare: The political economy of corporate environmentalism. The Journal of Law and Economics 43: 583–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- May, Douglas R., Cuifang Li, Jennifer Mencl, and Ching-Chu Huang. 2014. The ethics of meaningful work: Types and magnitude of job-related harm and the ethical decision-making process. Journal of Business Ethics 121: 651–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKelvie, Alexander, J. Michael Haynie, and Veronica Gustavsson. 2011. Unpacking the uncertainty construct: Implications for entrepreneurial action. Journal of Business Venturing 26: 273–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, Joan Marie, and Robert J. Harvey. 2007. The effect of moral intensity on ethical judgment. Journal of Business Ethics 72: 335–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, Jeffery S., and Benjamin J. Warnick. 2016. Should we require every new venture to be a hybrid organization? Journal of Management Studies 53: 630–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McMullen, Jeffery S., and Dean A. Shepherd. 2006. Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Academy of Management Review 31: 132–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McWilliams, Abagail, and Donald Siegel. 2001. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Academy of Management Review 26: 117–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, Alex, ed. 2008. Social Entrepreneurship: New Models of Sustainable Social Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Bohm, Vicki. 2000. Creating incentives for environmentally enhancing technological change: Lessons from 30 years of US energy technology policy. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 65: 125–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, Anne-Claire, and Filipe Santos. 2013. Inside the hybrid organization: Selective coupling as a response to competing institutional logics. Academy of Management Journal 56: 972–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Packer, Herbert L. 1968. The Limits of the Criminal Sanction. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patzelt, Holger, and Dean A. Shepherd. 2011. Recognizing opportunities for sustainable development. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice 35: 631–52. [Google Scholar]

- Philips, Sarah. 2007. A Brief History of Facebook. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2007/jul/25/media.newmedia (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Plummer, Lawrence A., J. Michael Haynie, and Joy Godesiabois. 2007. An essay on the origins of entrepreneurial opportunity. Small Business Economics 28: 363–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, Michael E. 1980. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Michael E., and Mark R. Kramer. 2006. Strategy & Society: The Link Between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility. Harvard Business Review 84: 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Michael, and Claas Van der Linde. 1995. Green and Competitive: Ending the Stalemate. Harvard Business Review 73: 120–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rest, James R. 1979. Development in Judging Moral Issues. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rest, James R. 1986. Moral Development: Advances in Research and Theory. New York: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Saebi, Tina, Nicolai J. Foss, and Stefan Linder. 2019. Social Entrepreneurship Research: Past Achievements and Future Promises. Journal of Management 45: 70–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheaf, David J., Andrew C. Loignon, Justin W. Webb, Eric D. Heggestad, and Matthew S. Wood. 2020. Measuring opportunity evaluation: Conceptual synthesis and scale development. Journal of Business Venturing 35: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, Douglas A., and Margaret Cording. 2006. A corporate social performance–corporate financial performance behavioral model for consumers. Academy of Management Review 31: 540–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, William H., and Vincent Barry. 2015. Moral Issues in Business. Boston: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, Herbert A. 1979. Rational decision making in business organizations. American Economic Review 69: 493–513. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Brett R., Geoffrey M. Kistruck, and Benedetto Cannatelli. 2016. The impact of moral intensity and desire for control on scaling decisions in social entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics 133: 677–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Wendy K., Michael Gonin, and Marya L. Besharov. 2013. Managing social-business tensions: A review and research agenda for social enterprise. Business Ethics Quarterly 23: 407–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strong, Kelly C., and G. Dale Meyer. 1992. An integrative descriptive model of ethical decision making. Journal of Business Ethics 11: 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Shelley E. 1975. On inferring ones own attitudes from ones behavior: Some delimiting conditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 31: 126–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]