Corporate Social Responsibility Engagement through Social Media. Evidence from the University of Salerno

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- To investigate the extent to which UNISA is exploiting the potential of SM tools (i.e., Twitter) to disclose CSR information and engage with stakeholders; and

- (2)

- To inquire into the degree of interactions with stakeholders and the communication direction and balance between UNISA and its stakeholders.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Background

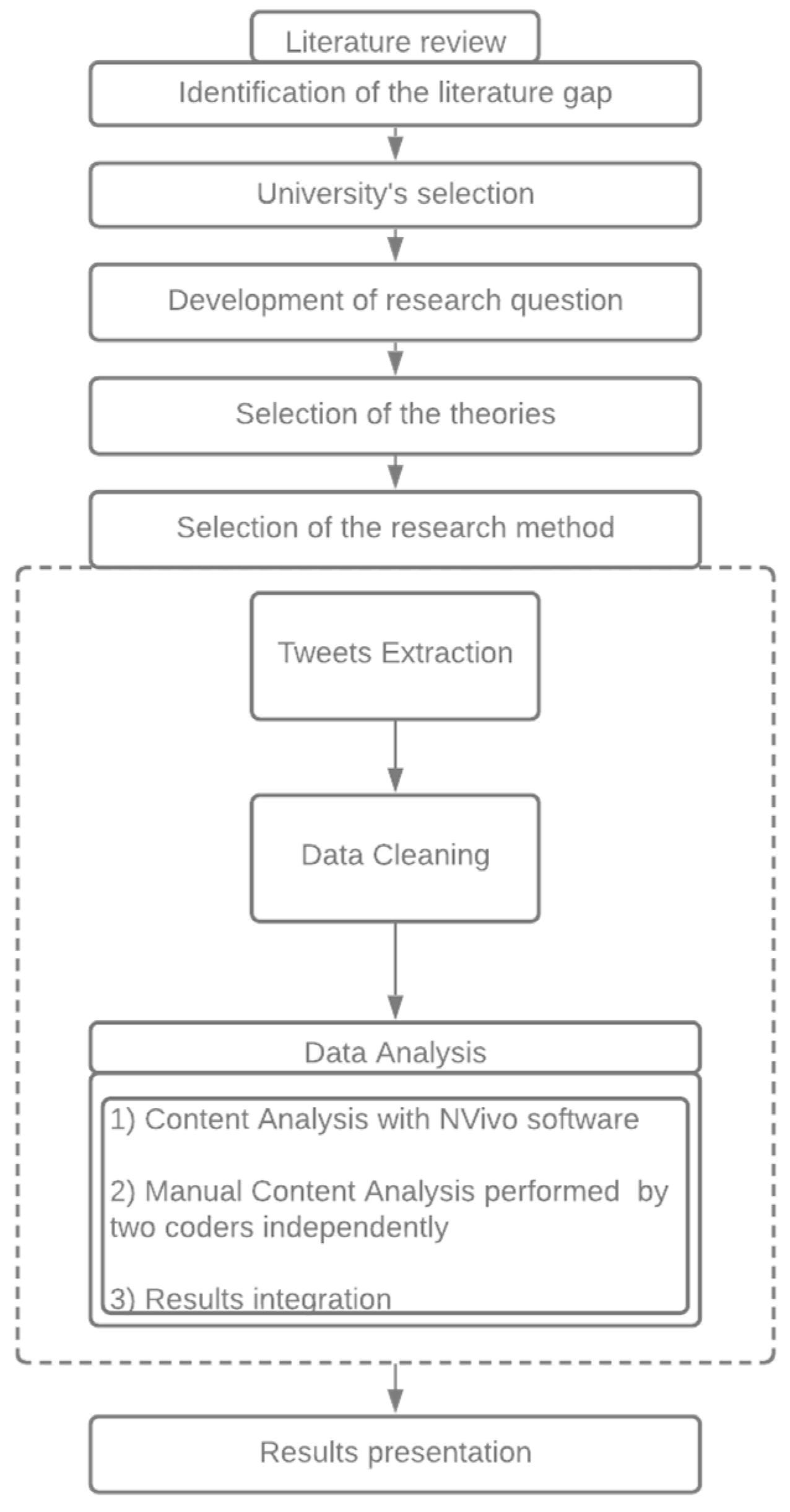

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Context Description: The University of Salerno and ITS CSR practices

3.2. Research Methods

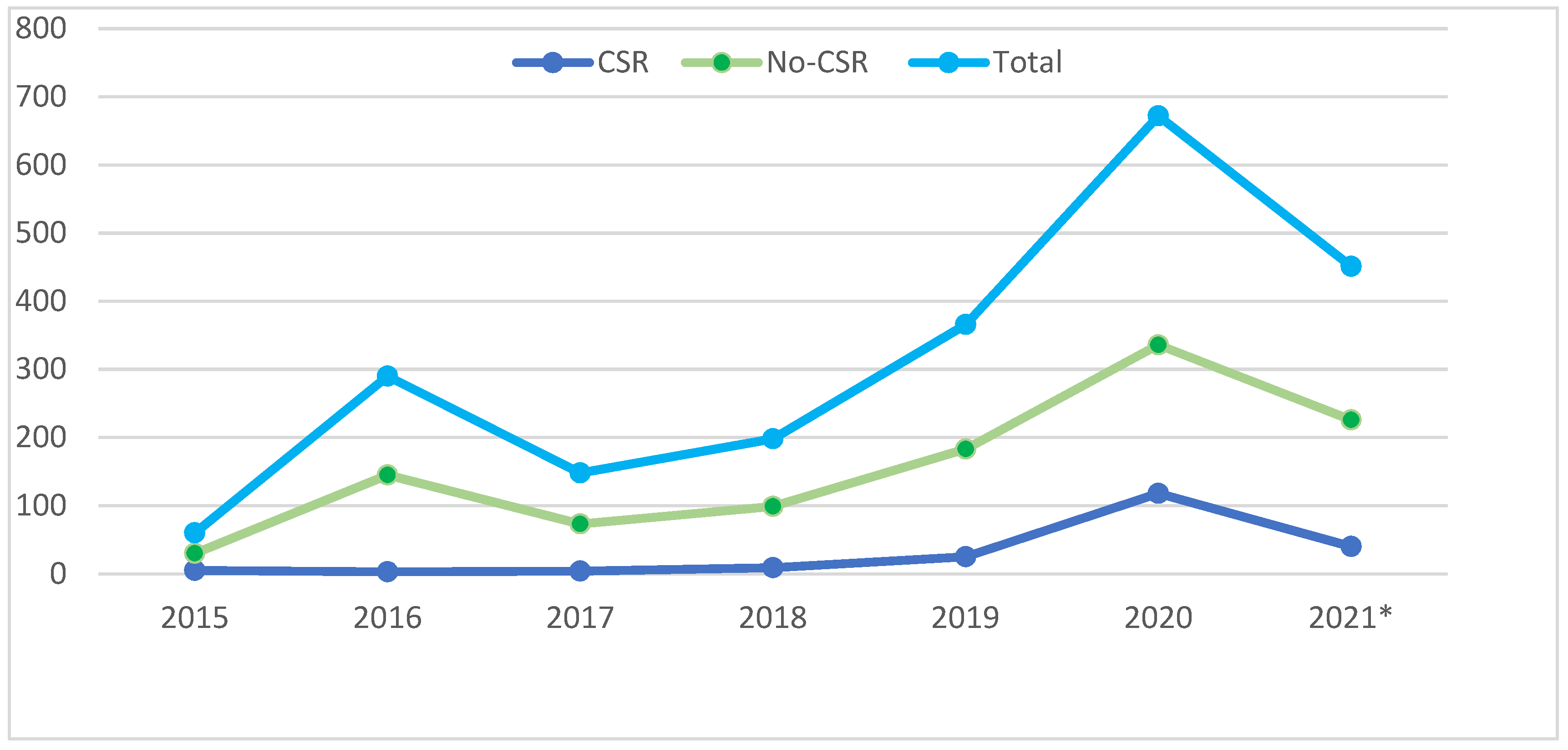

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adhikariparajuli, Mahalaxmi, Abeer Hassan, and Mary Fletcher. 2021. Integrated Reporting Implementation and Core Activities Disclosure in UK Higher Education Institutions. Administrative Sciences 11: 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development Goals, ONU. 2015. Available online: https://unric.org/it/agenda-2030/ (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Alonso-Almeida, Marìa del Mar, Fredric Marimon, Fernando Casani, and Jesùs Rodriguez-Pomeda. 2015. Diffusion of sustainability reporting in universities: Current situation and future perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production 106: 144–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Yi, H. Davey, Harund Harun, Zebin Jin, Xin Qiao, and Qun Yu. 2019. Online sustainability reporting at universities: The case of Hong Kong. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 11: 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilani, Barbara, and Alessandro Lovari. 2009. Social networks and university communication: Is Facebook a new opportunity? An Italian exploratory study. Paper present at the 12th International QMOD and Toulon-Verona Conference on Quality Service Sciences (ICQSS), Verona, Italy, August 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Aversano, Natalia, Ferdinando Di Carlo, Giuseppe Sannino, Paolo Tartaglia Polcini, and Rosa Lombardi. 2020a. Corporate social responsibility, stakeholder engagement, and universities: New evidence from the Italian scenario. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 1892–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aversano, Natalia, Giuseppe Nicolò, Giuseppe Sannino, and Paolo Tartaglia Polcini. 2020b. The Integrated Plan in Italian public universities: New patterns in intellectual capital disclosure. Meditari Accountancy Research 28: 655–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, Debra, and Julie Wilems. 2012. Facing off: Facebook and higher education. In Misbehavior Online Higher Education: Cutting-Edge Technologies in Higher Education. Bingley: Emerald, pp. 53–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington, Jan, Judy Brown, and Bob Frame. 2007. Accounting technologies and sustainability assessment models. Ecological Economics 61: 224–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, Monica, and Giacomo Manetti. 2017. Facebook as a tool for supporting dialogic accounting? Evidence from large philanthropic foundations in the United States. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 30: 874–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bellucci, Monica, Lorenzo Simoni, Diletta Acuti, and Giacomo Manetti. 2019. Stakeholder engagement and dialogic accounting: Empirical evidence in sustainability reporting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 32: 1467–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bezani, Ioni. 2010. Intellectual capital reporting at UK universities. Journal of Intellectual Capital 11: 179–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusca, Isabel, Sandra Cohen, Francesca Manes-Rossi, and Giuseppe Nicolò. 2020. Intellectual capital disclosure and academic rankings in European universities: Do they go hand in hand? Meditari Accountancy Research 28: 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, Joanne. 1999. Going beyond labels: A framework for profiling institutional stakeholders. Contemporary Education 70: 5. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, Pablo G., Encarna Guillamon-Saorin, and Beatriz Garcìa Osma. 2020. Stakeholders versus Firm Communication in Social Media: The Case of Twitter and Corporate Social Responsibility Information. European Accounting Review 30: 31–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Archie B. 1979. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Academy of Management Review 4: 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Archie B. 1991. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the Morai management of organisational stakeholders. Business Horizons 34: 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Archie B. 2021. Corporate Social Responsibility: Perspectives on the CSR Construct’s Development and Future. Business & Society 60: 1258–78. [Google Scholar]

- Castelo, Branco Manuel, and Rodriguez Lùcia Lima. 2008. Factors Influencing Social Responsibility Disclosure by Portuguese Companies. Journal of Business Ethics 83: 685–701. [Google Scholar]

- Ceulemans, Kim, Ingrid Molderez, and Luc Van Liedekerke. 2015. Sustainability reporting in higher education: A comprehensive review of the recent literature and paths for further research. Journal of Cleaner Production 106: 127–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazza, Laura, and Paolo Saluto. 2020. Universities and Multistakeholder Engagement for Sustainable Development: A Research and Technology Perspective. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 68: 1173–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Sordo, Carlotta, Federica Farneti, James Guthrie, Silvia Pazzi, and Benedetta Siboni. 2016. Social reports in Italian universities: Disclosures and preparers’ perspective. Meditari Accountancy Research 24: 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dima, Alina Mihaela, Simona Vasilache, Valentina Ghinea, and Simona Agoston. 2013. A model of academic social responsibility. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences 38: 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Marc J., and Sally K. Widener. 2010. Identification and use of sustainability performance measures in decision-making. Journal of Corporate Citizenship 40: 43–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, Benedetta, Maria Rosaria Sessa, Daniela Sica, and Ornella Malandrino. 2021a. Exploring Corporate Social Responsibility in the Italian wine sector through websites. The TQM Journal 33: 222–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, Benedetta, Maria Rosaria Sessa, Daniela Sica, and Ornella Malandrino. 2021b. Exploring the link between customers’ safety perception and the use of information technology in the restaurant sector during the COVID-19. An empirical analysis in the Campania Region, in Visvizi, Troisi, Research Research and Innovation Forum 2021. In Managing Continuity, Innovation, and Change in the Post-Covid World: Technology, Politics and Society. Cham: Springer, ISBN 978-3-030030-8431084310-6. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero-Ferrero, Idoya, Marìa Ángeles Fernández-Izquierdo, Marìa Jesùs Muñoz-Torres, and Lucìa Bellés-Colomer. 2018. Stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting in higher education: An analysis of key internal stakeholders’ expectations. International Journal of Advertising 19: 313–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, Alberto, Amanda Macdonald, Emily Dandy, and Paul Valenti. 2011. The state of sustainability reporting at Canadian universities. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 12: 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, Edward R. 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston: Pitman Publishing Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Gamage, Pandula, and Nick Sciulli. 2017. Sustainability reporting by Australian universities. Australian Journal of Public Administration 76: 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, Elena, Alberto Romolini, Silvia Fissi, and Marco Contri. 2020. Toward the Dissemination of Sustainability Issues through Social Media in the Higher Education Sector: Evidence from an Italian Case. Sustainability 12: 4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, Michelle. 2007. Stakeholder Engagement: Beyond the Myth of Corporate Responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics 74: 315–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, Suraya, Mohamad Taha Ijab, Hidayah Sulaiman, Rina Md Anwar, and Azah Anir Norman. 2017. Social media for environmental sustainability awareness in higher education. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 18: 474–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayes, Andrew F., and Klaus Krippendorf. 2007. Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication Methods and Measures 1: 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayter, Christopher S., and Daniel R. Cahoy. 2018. Toward a strategic view of higher education social responsibilities: A dynamic capabilities approach. Strategic Organization 16: 12–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörisch, Jacob, R. Edward Freeman, and Stefan Schaltegger. 2014. Applying stakeholder theory in sustainability management: Links, similarities, dissimilarities, and a conceptual framework. Organization & Environment 27: 328–46. [Google Scholar]

- Jongbloed, Ben, Jüregn Enders, and Carlo Salerno. 2008. Higher education and its communities: Interconnections, interdependencies and a research agenda. Higher Education 56: 303–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashmanian, Richard M., Richard P. Wells, and Cheryl Keenan. 2011. Corporate environmental sustainability strategy: Key elements. Journal of Corporate Citizenship 44: 107–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietzmann, Jan H., Kristopher Hermkens, Ian P. McCarthy, and Bruno S. Silvestre. 2011. Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media. Business Horizons 54: 241–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, Kyung-Sun, Sei-Ching Joanna, and Tien-I Tsai. 2014. Individual differences in social media use for information seeking. The Journal of Academic Librarianship 40: 171–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, Charles, and Linda K. Kaye. 2014. ‘To tweet or not to tweet?’ A comparison of academics’ and students’ usage of Twitter in academic contexts. Innovations in Education and Teaching International 53: 145–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotecha, Piyushi. 2010. Civic Engagement and Social Development. Paper present at the Presentation to the Bellagio Conference of Talloires Network, Bellagio, Italy, March 23–27; Available online: http://talloiresnetwork.tufts.edu/wp-?-content/uploads/PiyushiKotechaBellagioPresentation.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2018. Content Analysis, 4th ed. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Lodhia, Sumit, Amanpreet Kaur, and Gerard Stone. 2020. The use of social media as a legitimation tool for sustainability reporting: A study of the top 50 Australian Stock Exchange (ASX) listed companies. Meditari Accountancy Research 28: 613–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopatta, Kerstin, and Reemda Jaeschke. 2014. Sustainability Reporting at German and Austrian Universities. International Journal of Education Economics and Development 5: 66–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, Rodrigo. 2011. The state of sustainability reporting in universities. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 12: 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes Rossi, Francesca, Giuseppe Nicolò, and Paolo Tartaglia Polcini. 2018. New trends in intellectual capital reporting: Exploring online intellectual capital disclosure in Italian universities. Journal of Intellectual Capital 19: 814–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manetti, Giacomo, and Manetti Bellucci. 2016. The use of social media for engaging stakeholders in sustainability reporting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 29: 985–1011. [Google Scholar]

- McCay-Peet, Lori, and Anabel Quan-Haase. 2017. What is social media and what questions can social media research help us answer. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods. London: SAGE, pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mergel, Ines. 2013. A framework for interpreting social media interactions in the public sector. Government Information Quarterly 30: 327–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miles, Matthew, and A. Michael Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Moggi, Sara. 2019. Social and environmental reports at universities: A Habermasian view on their evolution. Accounting Forum 43: 283–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsing, Mette. 2006. Strategic CSR communication: Telling others how good you are. In Management Models for Corporate Social Responsibility. Berlin: Springer, pp. 238–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ndou, Valentina, Giustina Secundo, John Dumay, and Elvin Gjevori. 2018. Understanding intellectual capital disclosure in online media Big Data: An exploratory case study in a university. Meditari Accountancy Research 26: 499–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolò, Giuseppe, Francesca Manes-Rossi, Johan Christiaens, and Natalia Aversano. 2020. Accountability through intellectual capital disclosure in Italian Universities. Journal of Management and Governance 24: 1055–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolò, Giuseppe, Natalia Aversano, Giuseppe Sannino, and Paolo Tartaglia Polcini. 2021a. Investigating Web-Based Sustainability Reporting in Italian Public Universities in the Era of COVID-19. Sustainability 13: 3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolò, Giuseppe, Nicola Raimo, Paolo Tartaglia Polcini, and Filippo Vitolla. 2021b. Unveiling the link between performance and Intellectual Capital disclosure in the context of Italian Public universities. Evaluation and Program Planning 88: 101969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagiotopoulos, Panagiotis, Alinaghi Ziaee Bigdeli, and Steven Sams. 2014. Citizen–government collaboration on social media: The case of Twitter in the 2011 riots in England. Government Information Quarterly 31: 349–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, Amy. 2014. Literature review on social responsibility in higher education. In UNESCO Chair for Community Based Research and Social Responsibility in Higher Education. Victoria: University of Victoria. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrino, Catherine, and Sumit Lodhia. 2012. Climate change accounting and the Australian mining industry: Exploring the links between corporate disclosure and the generation of legitimacy. Journal of Cleaner Production 36: 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Robert A. 1997. Stakeholder theory and a principle of fairness. Business Ethics Quarterly 7: 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, Simone, Sara Moggi, Sara Caputo, and Pierfelice Rosato. 2020. Social media as stakeholder engagement tool: CSR communication failure in the oil and gas sector. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 28: 849–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, Anne H., and Katherine A. Hynan. 2014. Corporate communication, sustainability, and social media: It’s not easy (really) being green. Business Horizons 57: 747–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Menendez, Ana Saura, Josè Ramòn, and Cesar Alvarez-Alonso. 2018. Understanding #WorldEnvironmentDay User Opinions in Twitter: A Topic-Based Sentiment Analysis Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15: 2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez Bolívar, Manuel Pedro, Raquel Garde Sánchez, and Antonio M. López Hernández. 2013. Online disclosure of corporate social responsibility information in leading Anglo-American universities. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 15: 551–75. [Google Scholar]

- RUS—Rete delle Università per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile. 2020. Available online: https://sites.google.com/unive.it/rus/home (accessed on 24 August 2021).

- Rutter, Richard, Stuart Roper, and Fiona Lettice. 2016. Social media interaction, the university brand and recruitment performance. Journal of Business Research 69: 3096–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schroder, Philipp. 2021. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication via social media sites: Evidence from the German banking industry. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 26: 636–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siboni, Benedetta, Carlotta Del Sordo, and Silvia Pazzi. 2013. Sustainability Reporting in State Universities: An Investigation of Italian Pioneering Practices. International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development (IJSESD) 4: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, Daniela, Benedetta Esposito, Maria Rosaria Sessa, Ornella Malandrino, and Stefania Supino. 2021. Gender path in Italian universities: Evidence from University of Salerno. Paper present at the 27nd International Sustainable Development Research Society Conference, Mid Sweden University, Östersund, Sweden, July 13–15. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman, Mark C. 1995. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review 20: 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, Ian, and Jan Bebbington. 2005. Social and environmental reporting in the UK: A pedagogic evaluation. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 16: 507–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trireksani, Terri, Yun-Ting Zeng, and Hadrian Geri Djajadikerta. 2021. Extent of sustainability disclosure by Australian public universities: Inclusive analysis of key reporting media. Australian Journal of Public Administration 16: 507–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallaeys, François. 2007. Responsabilidad Social Universitaria. Propuesta para una Definición Madura y Eficiente, Programa para la Formación en Humanidades—Tecnológico de Monterrey. Available online: http://www.bibliotecavirtual.info/wpcontent/uploads/2011/12/Responsabilidad_Social_Universitaria_Francois_Vallaeys.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Van Weenen, Hans. 2000. Towards a vision of a sustainable university. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 1: 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vitolla, Filippo, Nicola Raimo, and Michele Rubino. 2019a. Appreciations, criticisms, determinants, and effects of integrated reporting: A systematic literature review. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 26: 518–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitolla, Filippo, Nicola Raimo, Michele Rubino, and Antonello Garzoni. 2019b. The impact of national culture on integrated reporting quality. A stakeholder theory approach. Business Strategy and the Environment 28: 1558–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wukich, Clayton, and Ines Mergel. 2016. Reusing social media information in government. Government Information Quarterly 33: 305–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yongvanich, Kittiya, and James Guthrie. 2007. Legitimation strategies in Australian mining extended performance reporting. Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting 11: 156–77. [Google Scholar]

| Internal Stakeholders | External Stakeholders |

|---|---|

| Students and families | Associations |

| Future students | Schools |

| Freshmen | Local authorities and Public Administration |

| Students | Ministries |

| Graduates | Local enterprises |

| Families | |

| Employees | |

| Technical and administrative | |

| Professors | |

| Researchers | |

| In training |

| Items | Carroll’s Pyramid | Bunch of Words |

|---|---|---|

| Philanthropic | Be a good corporate citizen → Desired | “Territory OR Occupational OR Employment OR Training OR Education OR Health OR Diversity OR Inclusion OR Gender OR Equality OR Community” |

| Ethical | Be ethical → Expected | “Energy OR Environmental OR Environment OR Water OR Waste OR Emission OR Emissions OR Biodiversity OR Effluents OR Material OR Sustainability” |

| Legal | Obey the law → Required | “Public policy OR Regulations OR Security OR Investment OR Compliant OR Compliance” |

| Economic | Be profitable → Required | “Performance OR Revenues OR Financial viability OR Economic viability” |

| Total CSR Tweet | Total NO-CSR Tweet | Total Tweet | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | St. Dev. | Mean | St. Dev | Mean | St. Dev. | |

| Like | 68.5 | 69.2 | 26.3 | 28.5 | 42.6 | 46.1 |

| Retweet | 2.75 | 2.01 | 2.62 | 1.98 | 2.69 | 2.01 |

| Obs | 206 | 887 | 1093 | |||

| Obs% | 18.85% | 81.15% | 100% | |||

| Philanthropic | Ethical | Legal | Economic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | St. Dev. | Mean | St. Dev. | Mean | St. Dev. | Mean | St. Dev. | |

| Like | 25.3 | 22.1 | 18.2 | 17.8 | 20.6 | 19.7 | 15.2 | 14.8 |

| Retweet | 2.54 | 1.90 | 3.32 | 2.60 | 2.82 | 1.87 | 2.78 | 1.70 |

| Obs | 104 | 42 | 35 | 25 | ||||

| Obs% | 50.48% | 20.39% | 17.00% | 12.13% | ||||

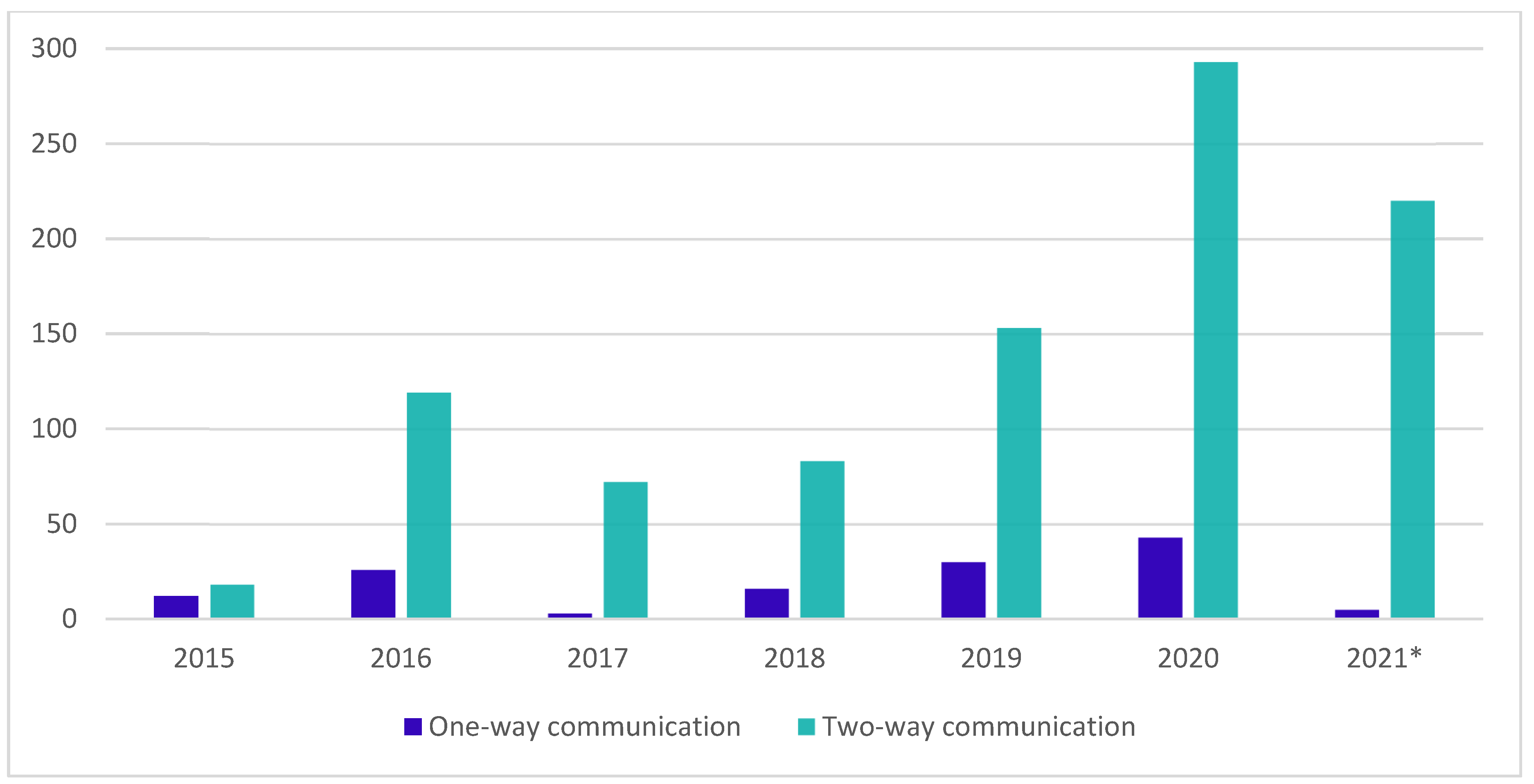

| Direction Type | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 * | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| One-way communication | 12 | 40 | 26 | 17.93 | 3 | 4 | 16 | 16.16 | 30 | 16.40 | 43 | 12.80 | 5 | 2.23 | 135 | 12.35 |

| Two-way communication | 18 | 60 | 119 | 82.07 | 72 | 96 | 83 | 83.84 | 153 | 83.60 | 293 | 87.20 | 220 | 97.77 | 958 | 87.65 |

| Informative communication | 29 | 96.66 | 143 | 98.62 | 73 | 97.34 | 95 | 95.95 | 173 | 94.53 | 216 | 64.28 | 150 | 64.28 | 880 | 66.66 |

| Interacting communication | 1 | 3.34 | 2 | 1.38 | 2 | 2.66 | 4 | 4.04 | 10 | 5.46 | 120 | 35.71 | 75 | 35.71 | 213 | 33.34 |

| Total tweets per year | 30 | 2.74 | 145 | 13.26 | 75 | 6.86 | 99 | 9.05 | 183 | 16.74 | 336 | 30.74 | 225 | 20.58 | 1093 | 100 |

| Direction Type | Total | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| One-way communication | 20 | 10.19 |

| Two-way communication | 185 | 89.81 |

| Informative communication | 151 | 73.30 |

| Interacting communication | 55 | 26.70 |

| Total CSR tweets | 206 | 100% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Esposito, B.; Sessa, M.R.; Sica, D.; Malandrino, O. Corporate Social Responsibility Engagement through Social Media. Evidence from the University of Salerno. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11040147

Esposito B, Sessa MR, Sica D, Malandrino O. Corporate Social Responsibility Engagement through Social Media. Evidence from the University of Salerno. Administrative Sciences. 2021; 11(4):147. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11040147

Chicago/Turabian StyleEsposito, Benedetta, Maria Rosaria Sessa, Daniela Sica, and Ornella Malandrino. 2021. "Corporate Social Responsibility Engagement through Social Media. Evidence from the University of Salerno" Administrative Sciences 11, no. 4: 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11040147

APA StyleEsposito, B., Sessa, M. R., Sica, D., & Malandrino, O. (2021). Corporate Social Responsibility Engagement through Social Media. Evidence from the University of Salerno. Administrative Sciences, 11(4), 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11040147