Towards a Model of Muslim Women’s Management Empowerment: Philosophical and Historical Evidence and Critical Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Problems: Definitional, Neoliberal, Globalisational, Mythic and Fallacious

2.1. Definitional

2.2. Neoliberalism

2.3. Globalisation

2.4. Myths and Fallacies

3. Evidentiary Sources for Empowerment

3.1. Philosophic Evidence: Core Islamic Texts

3.2. Historical-Biographical Evidence: Women in Politics, War, Economics, Jurisprudence and Scholarship

4. Approaches in Constructing a Model: Intellectual and Cultural Capital, Multiple Modernities, Cultural Security and Postcolonial Critiques

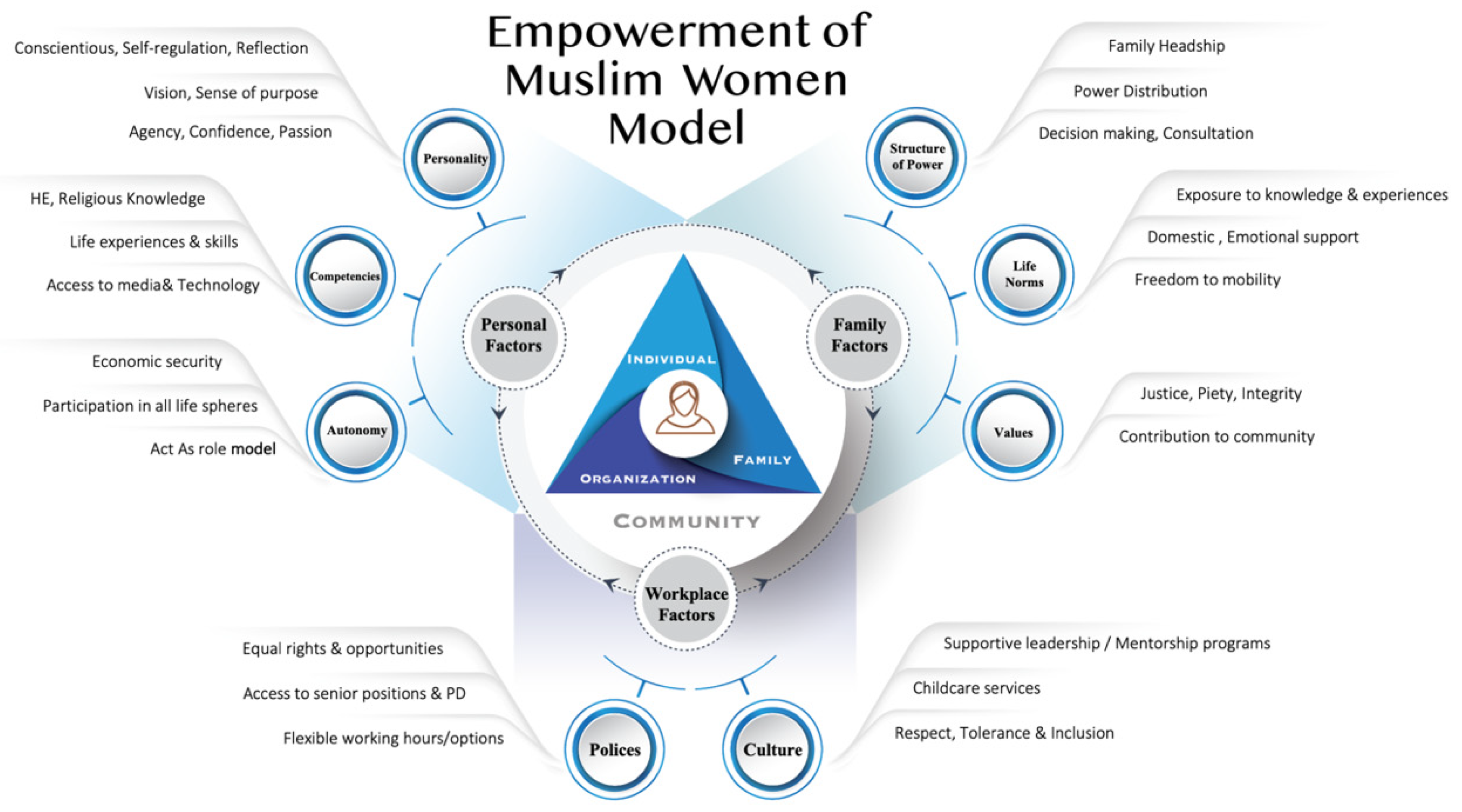

5. Towards a New Model of Muslim Women’s Empowerment

- A high level of conscientiousness, self-regulation, and self-reflection.

- A vision for the future or a sense of purpose.

- An ability to show agency, confidence, and passion to contribute.

- Higher education and religious knowledge,

- Exposure to different forms of life experiences, and

- Access to all forms of media and technology.

- Economic independence through paid jobs or having own financial resources,

- Participation in all spheres of life (e.g., social, economic, political), and

- Acting as a role model for others to follow.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbasi, Salma. 2015. Impact of ICTS on Muslim women. In The Routledge Handbook of Gender and Development. Edited by Anne Coles, Leslie Gray and Janet Momsen. London: Routledge, pp. 353–64. [Google Scholar]

- Abdalla, Ikhlas. 2015. Being and becoming a leader: Arabian Gulf women managers’ perspectives. International Journal of Business and Management 10: 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Lughod, Lila. 2013. Do Muslim Women Need Saving? Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Achcar, Gilbert. 2002. The Clash of Barbarisms. Boulder: Paradigm. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerly, Brooke. 1997. What’s in a design? The effects of NGO programme delivery choices on women’s empowerment in Bangladesh. In Getting Institutions Right for Women in Development. Edited by Anne Marie Goetz. London: Zed, pp. 140–58. [Google Scholar]

- Adovasio, James, Olega Soffer, and Jake Page. 2016. The Invisible Sex: Uncovering the True Roles of Women in Prehistory. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Leila. 1992. Women and Gender in Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Leila. 2012. A Quiet Revolution: The Veil’s Resurgence, from the Middle East to America. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Al Wazni, Anderson Beckmann. 2015. Muslim women in America and hijab: A study of empowerment, feminist identity, and body image. Social work 60: 325–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, Abbas. 1988. Scaling an Islamic work ethic. Journal of Social Psychology 128: 575–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jabri, Mohammad. 2014. Democracy, Human Rights and Law in Islamic Thought. London: I. B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Allagui, Ilhem, and Abeer Al-Najjar. 2018. From women empowerment to nation branding: A case study from the United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Communication 12: 18. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sa’l, Ibn. 2017. Consorts of the Caliphs: Women and the Court of Baghdad. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alwani, Zainab. 2013. Muslim women as religious scholars: A historical survey. In Muslima Theology: The Voices of Muslim Women Theologians. Edited by Ednan Aslan, Marcia Hermansen and Elif Medeni. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, pp. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Amann, Wolfgang, and Agata Stachowicz-Stanusch, eds. 2013. Integrity in Organizations: Building the Foundations for Humanistic Management. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Augsburg, Kristin, Isabell Claus, and Kasim Randeree. 2009. Leadership and the Emirati Woman: Breaking the Glass Ceiling in the Arabian Gulf. Berlin: Lit Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Bahraini, Zainab. 2001. Women of Babylon: Gender and Representation in Mesopotamia. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, Albert. 2006. Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science 1: 164–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, Subhabrata. 2008. Necrocapitalism. Organization Studies 29: 1541–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barazangi, Nimat. 2016. Women’s Identity and Rethinking the Hadith. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Barbert, Elizabeth. 1995. Women’s Work, The First 20,000 Years: Women, Cloth, and Society in Early Times. New York: W. W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Barkawi, Tarak, and Mark Laffey. 2006. The postcolonial moment in security studies. Review of International Studies 32: 329–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlas, Asma. 2002. Believing Women in Islam: Unreading Patriarchal Interpretations of the Qur’an. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baskerville, Rachel. 2003. Hofstede never studied culture. Accounting, Organizations and Society 28: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batliwala, Srilatha. 1994. The meaning of empowerment: New concepts from action. In Population Policies Reconsidered: Health, Empowerment and Rights. Edited by Gita Sen, Adrienne Germain and Lincoln Chen. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 127–38. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Lois, and Nikki Keddie. 1978. Women in the Muslim World. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Lynn. 2002. Using Empowerment and Social Inclusion for Pro-Poor Growth: A Theory of Social Change, Working Draft of Background Paper for Social Development Strategy Paper. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Clinton. 2010. Muslim Women of Power: Gender, Politics and Culture in Islam. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua, Alexander. 2018. The Republic of Arabic Letters: Islam and the European Enlightenment. Cambridge: Belknap Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bilgin, Pinar. 2008. Thinking past ‘western’ IR? Third World Quarterly 29: 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouachrine, Ibtissam. 2015. Women and Islam: Myths, Apologies, and the Limits of Feminist Critique. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1993. The Field of Cultural Production. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boyar, Ebru, and Kate Fleet. 2016. Ottoman Women in Public Space. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Branine, Mohamed. 2011. Managing Across Cultures. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Brosius, Maria. 1998. Women in Ancient Persia, 559–331 BCE. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cavelty, Myriam, and Thierry Balzacq, eds. 2017. Routledge Handbook of Security Studies, 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Charlier, Sophie, Lisette Caubergs, Nicole Malpas, and Ernestine Kakiba. 2007. The Women Empowerment Approach. Brussels: Commission on Women and Development, DGDC. [Google Scholar]

- Charmes, Jacques, and Saskia Wieringa. 2003. Measuring women’s empowerment: An assessment of the gender related development index and gender empowerment index. Journal of Human Development 4: 419–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, Imran, Farhan Nosheen, and Muhammad Lodhi. 2012. Women empowerment in Pakistan with special reference to Islamic viewpoint: An empirical study. Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences 32: 171–83. [Google Scholar]

- Chhokar, Jagdeep, Felix Brodbeck, and Robert House, eds. 2019. Culture and Leadership across the World. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Chraibi, Radia, and Wendy Cukier. 2017. Muslim women in senior management positions in Canada. In Muslim Minorities, Workplace Diversity and Reflexive HRM. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 162–82. [Google Scholar]

- Croft, Stuart. 2012. Constructing ontological insecurity: The insecuritization of Britain’s Muslims. Contemporary Security Policy 33: 219–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabashi, Hamid. 2013. Being a Muslim in the World. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Dabashi, Hamid. 2015. Can Non-Europeans Think? London: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, William. 2016. The Limits of Neoliberalism: Authority, Sovereignty and the Logic of Competition. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, Manisha A. 2010. Hope in Hard Times: Women’s Empowerment and Human Development. Human Development Reports. Paris: United Nations Development Programme. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, Elin, Denise Varney, and Candice Amich. 2017. Performance, Feminism and Affect in Neoliberal Times. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Dierksmeier, Claus. 2016. Reframing Economic Ethics. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Dresch, Paul. 2013. Introduction: Societies, identities and global issues. In Monarchies and Nations: Globalisation and Identity in the Arab states of the Gulf. Edited by Paul Dresch and James Piscatori. London: I. B. Tauris, pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstadt, Shmuel. 2000. Multiple modernities. Daedalus 129: 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstadt, Shmuel. 2005. Multiple Modernities. New Brunswick: Transaction. [Google Scholar]

- El Cheikh, Nadia. 2015. Women, Islam, and Abbasid Identity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- El Fadl, Khaled. 2001. Speaking in God’s Name: Islamic Law, Authority and Women. Oxford: Oneworld. [Google Scholar]

- ElKaleh, Eman, and Eugenie Samier. 2013. The ethics of Islamic leadership: A cross-cultural approach for public administration. Administrative Culture 14: 188–211. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, Carolyn. 2008. Introduction: Markets, communities, and empowerment. In Global Empowerment of Women: Responses to Globalization and Politicized Religions. Edited by Carolyn Elliott. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Farazmand, Ali. 1999. Globalization and public administration. Public Administration Review 59: 509–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricker, Miranda. 2007. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi, Leela. 1998. Postcolonial Theory. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrke-White, Donna. 2006. Face behind the Veil. New York: Citadel Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ghadanfar, Mahmud. 2001. Great Women of Islam. Riyadh: Darussalam. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, Barney, and Anselm Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago: Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, Godfrey. 2006. The Private World of Ottoman Women. London: Saqi. [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Brown, Sarah. 2001. Women’s activism in the Middle East: A historical perspective. In Women and Power in the Middle East. Edited by Suad Joseph and Susan Slyomoics. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Gram, Lu, Joanna Morrison, and Jolene Skordis-Worrall. 2019. Organising concepts of ‘Women’s empowerment’ for measurement: A typology. Social Indicators Research 143: 1349–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, Shirley. 2001. Arab Women in the Middle Ages: Private Lives and Public Roles. London: Saqi. [Google Scholar]

- Haeri, Shahla. 2020. The Unforgettable Queens of Islam: Succession, Authority, Gender. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hafez, Sherine. 2003. The Terms of Empowerment: Islamic Women Activists in Egypt. Cairo: American University of Cairo Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Budd, and Rajesh Tandon. 2017. Decolonization of knowledge, epistemicide, participatory research and higher education. Research for All 1: 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halton, Charles, and Saana Svärd. 2018. Women’s Writing of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Anthology of the Earliest Female Writers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hambly, Gavin, ed. 1998. Women in the Medieval Islamic World. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, Geert. 1991. Culture and Organizations: Software of the Mind. London: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, Geert. 1994. Cultures and Organizations. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- House, Robert, Paul Hanges, Mansour Javidan, Peter Dorfman, and Vipin Gupta, eds. 2004. Culture, Leadership, and Organizations. Thousand Oakes: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Huis, Marloes, Nina Hansen, Sabine Otten, and Robert Lensink. 2017. A three-dimensional model of women’s empowerment: Implications in the field of microfinance and future directions. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, Samuel. 1997. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, Celene. 2020. Women and Gender in the Qur’an. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jalajel, David. 2017. Women and Leadership in Islamic Law. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, Arif. 2018. Islam, Law and the Modern State. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Pauly, Christina. 2011. Women under Islam: Gender, Justice and the Politics of Islamic Law. London: I. B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, Suad, and Susan Slyomovics. 2001. Introduction. In Women and Power in the Middle East. Edited by Suad Joseph and Susan Slyomoics. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylania Press, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer, Naila. 1999. Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change 30: 435–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, Naila. 2001. Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. In Discussing Women’s Empowerment. Edited by Anne Sisask. Stockholm: SIDA, pp. 17–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantari, Behrooz. 1998. In Search of a Public Administration Paradigm: Is there anything to be Learned from Islamic Public Administration? International Journal of Public Administration 12: 1821–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, Mohammad. 2002. Freedom, Equality and Justice in Islam. Cambridge: Islamic Texts Society. [Google Scholar]

- Kamaly, Hossein. 2019. A History of Islam in 21 Women. London: Oneworld. [Google Scholar]

- Keddie, Nikki. 2002. Women in the limelight: Some recent books on Middle Eastern women’s history. International Journal of Middle East Studies 34: 553–75. [Google Scholar]

- Keddie, Amanda. 2011. Framing discourses of possibility and constraint in the empowerment of Muslim girls: Issues of religion, race, ethnicity and culture. Race Ethnicity and Education 14: 175–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keddie, Nikki, and Beth Baron, eds. 1991. Women in Middle Eastern History: Shifting Boundaries in Sex and Gender. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Mariam, ed. 2006. Islamic Democratic Discourse Theory, Debates, and Philosophical Perspectives. Lanham: Lexington. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Sher. 2017. Sovereign Women in a Muslim Kingdom: The Sultanahs of Aceh, 1641–1699. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Mariam, ed. 2019. It’s Not about the Burqa. London: Picador. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, Wanda. 2008. Women in Civil Society: The State, Islamism, and Networks in the UAE. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, Keith, and Michael Williams, eds. 1997. Critical Security Studies. London: UCL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kruk, Remke. 2014. The Warrior Women of Islam: Female Empowerment in Arabic Popular Literature. London: I. B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Kundu, Suman, and Ananya Chakraborty. 2012. An empirical analysis of women empowerment within Muslim community in Murshidabad district of West Bengal, India. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences 2: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Küng, Hans. 2004. Islam: Past, Present, and Future. Oxford: Oneworld. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtiş, Tuğçe, Glenn Adams, and Sara Estrada-Villalta. 2016. Decolonizing empowerment: Implications for sustainable well-being. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 16: 387–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzman, Charles. 2019. The Missing Martyrs: Why Are There So Few Muslim Terrorists? Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lamrabet, Asma. 2016. Women in the Qur’an: An Emancipatory Reading. Markfield: Square View. [Google Scholar]

- Lean, Nathan. 2012. The Islamophobia Industry: How the Right Manufactures Fear of Muslims. London: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lion, Brigitte, and Cécile Michel, eds. 2016. The Role of Women in Work and Society in the Ancient Near East. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Lynham, Susan. 2002. A general method of theory-building research in applied disciplines. Advances in Developing Human Resources 4: 221–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, Anju, Sidney Schulerm, and Carol Boender. 2002. Measuring Women’s Empowerment as a Variable in International Development. Background Paper Prepared for the World Bank Workshop on Poverty and Gender, New Perspectives. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Measuring-Women%27s-Empowerment-as-a-Variable-in-Malhotra-Schuler/77dc832fa3899054ce001e7d47c44cb47f1af106 (accessed on 5 January 2021). [CrossRef]

- Mandal, Keshab. 2013. Concept and Types of Women Empowerment. International Forum of Teaching & Studies 9: 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, Robert. 1994. The Changing Face of National Security: A Conceptual Analysis. Westport: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- McSweeney, Brendan. 2002. Hofstede’s model of national cultural differences and their consequences: A triumph of faith-a failure of analysis. Human Relations 55: 89–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mernissi, Ftima. 1993. The Forgotten Queens of Islam. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Mernissi, Ftima. 2011. Beyond the Veil: Male-Female Dynamics in a Modern Muslim Society. London: Saqi Books. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe, Beverly. 2011. Women, empowerment and development in Arab Gulf states: A critical appraisal of goernance, culture and national human resource development (HRD) frameworks. Human Resource Development International 14: 131–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignolo, Walter. 2000. The geopolitics of knowledge and the colonial difference. Southern Atlantic Quarterly 101: 57–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignolo, Walter. 2011. The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nadwi, Mohammed. 2013. Al-Muhaddithat: The Women Scholars in Islam. Oxford: Interface Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, Jamal. 2009. The Status of Women under Islamic Law an Modern Islamic Legislation, 3rd ed. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ozgules, Muzaffer. 2017. Women Who Built the Ottoman World. London: I. B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, Douglas, and Rachel Woodlock, eds. 2016. Fear of Muslims? International Perspectives on Islamophobia. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan, Tariq. 2009. Islamic Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ripsman, Norrin, and T. Paul. 2010. Globalization and the National Security State. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, Lawrence. 1989. The Anthropology of Justice: Law as Culture in Islamic Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, Lawrence. 2018. Islam and the Rule of Justice: Image and Reality in Muslim Law and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sadiqi, Fatima, ed. 2011. Women in the Middle East and North Africa: Agents of Change. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Said, Edward. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Sakr, Naomi, ed. 2007. Women and Media in the Middle East. London: I. B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Saliba, George. 2007. Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Samier, Eugenie A. 2015a. Emirati Women’s Higher Educational Leadership Formation under Globalisation: Culture, Religion, Politics and the Dialectics of Modernisation. Gender and Education 27: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samier, Eugenie A. 2015b. The globalization of higher education as a societal and cultural security problem. Policy Futures in Education 13: 683–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarayrah, Yasin. 2004. Servant Leadership in the Bedouin-Arab Culture. Global Virtue Ethics Review 5: 58–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sayeed, Asma. 2013. Women and the Transmission of Religious Knowledge in Islam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Amartya. 1999. Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, Laura. 2013. Critical Approaches to Security. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Shiraev, Eric, and David Levy. 2017. Cross-cultural Psychology: Critical Thinking and Contemporary Applications. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi, Faegheh. 2010. Muslim Women in War and Crisis: Representation and Reality. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smither, Robert, and Alireza Khorsandi. 2009. The implicit personality theory of Islam. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 1: 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonbol, Amira. 2006. Beyond the Exotic: Women’s Histories in Islamic Societies. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sonneveld, Nadia, and Monika Lindbekk. 2017. Women Judges in the Muslim World. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Spellberg, Denise A. 1994. Politics, Gender, and the Islamic Past: The Legacy of ‘A’isha bint Abi Bakr. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spierings, Niels. 2015. Women’s Employment in Muslim Countries. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzeck, Heiko, Michael Pirson, Wolfgang Amann, Shiban Khan, and Ernst von Kimakowitz, eds. 2009. Humanism in Business. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spivak, Gayatri. 1988. Can the subaltern speak? In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. Edited by Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, pp. 271–313. [Google Scholar]

- Syed, Jawad, and Abbas Ali. 2010. Principles of employment relations in Islam. Employee Relations 32: 454–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaat, Nor, Aida Talaat, Syazrin Sharifuddin, Habibah Yahya, and Mohamed Majid. 2016. The Implementation of Islamic Management Practices at MYDIN. International Journal of Business and Management Invention 5: 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Thiong’o, Ngūgī. 1987. Decolonising the Mind. Harare: Zimbabwe Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Trompenaars, Fons, and Charles Hampden-Turner. 1997. Riding the Waves of Culture. London: Nicholas Brealey. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, Judith. 2008. Women, Family, and Gender in Islamic Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge, Jean M., and W. Keith Campbell. 2009. The Narcissism Epidemic: Living in the Age of Entitlement. New York: Atria. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2018. Cultural Rights and the Protection of Cultural Heritage. Geneva: United Nations Office of the High Commissioner. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/issues/escr/pages/culturalrightsprotectionculturalheritage.aspx (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Varghese, Thresiamma. 2011. Women empowerment in Oman: A study based on Women Empowerment Index. Far East Journal of Psychology and Business 2: 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Vivante, Bella. 2017. Daughters of Gaia: Women in the Ancient Mediterranean World. Westport: Greenwood. [Google Scholar]

- Wadud, Amina. 1999. Qur’an and Woman: Rereading the Sacred Text from a Woman’s Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wadud, Amina. 2006. Aishah’s legacy: The struggle for women’s rights within Islam. In The New Voices of Islam: Rethinking Politics and Modernity. Edited by Mehran Kamrava. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 201–4. [Google Scholar]

- Walther, Wiebke. 1993. Women in Islam: From Medieval to Modern Times. Princeton: Markus Wiener. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Max. 1968. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Bronwyn, Poh Ng, and Bettina Bastian. 2021. Hegemonic conceptualizations of empowerment in entrepreneuriship and their suitability for collective contexts. Administrative Sciences 11: 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, Darwish. 2000. Islamic work ethic: A moderator between organizational commitment and job satisfaction in a cross-cultural context. Personnel Review 30: 152–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahidi, Saadia. 2018. Fifty Million Rising: The New Generation of Working Women Transforming the Muslim World. New York: Nation Books. [Google Scholar]

- Zilfi, Madeline, ed. 1997. Women in the Ottoman Empire. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Samier, E.; ElKaleh, E. Towards a Model of Muslim Women’s Management Empowerment: Philosophical and Historical Evidence and Critical Approaches. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11020047

Samier E, ElKaleh E. Towards a Model of Muslim Women’s Management Empowerment: Philosophical and Historical Evidence and Critical Approaches. Administrative Sciences. 2021; 11(2):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11020047

Chicago/Turabian StyleSamier, Eugenie, and Eman ElKaleh. 2021. "Towards a Model of Muslim Women’s Management Empowerment: Philosophical and Historical Evidence and Critical Approaches" Administrative Sciences 11, no. 2: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11020047

APA StyleSamier, E., & ElKaleh, E. (2021). Towards a Model of Muslim Women’s Management Empowerment: Philosophical and Historical Evidence and Critical Approaches. Administrative Sciences, 11(2), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11020047