The Role of Multi-Actor Engagement for Women’s Empowerment and Entrepreneurship in Kerala, India

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Empowerment, Entrepreneurship and Multi-Actor Engagement

3. Context: Kerala

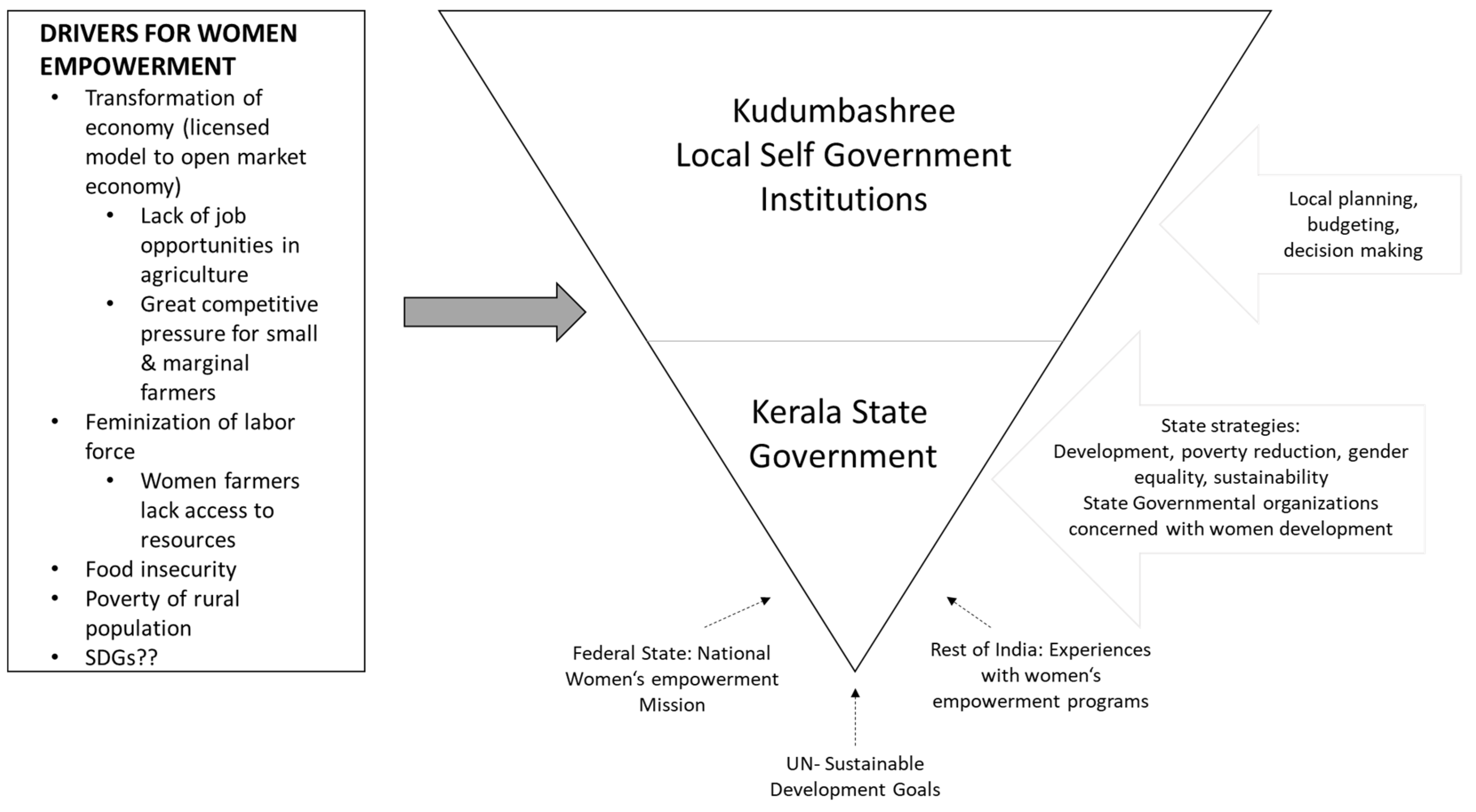

Drivers of the Need for Women’s Empowerment

4. Method

4.1. Case Study: Kudumbashree Mission

4.2. Evolution of the Multi-Actor Approach for Kudumbashree

4.3. The Working Model of Kudumbashree: The Role of Multiple Actors

4.3.1. State Actors

4.3.2. National and Federal State Actors

4.3.3. Local Actors

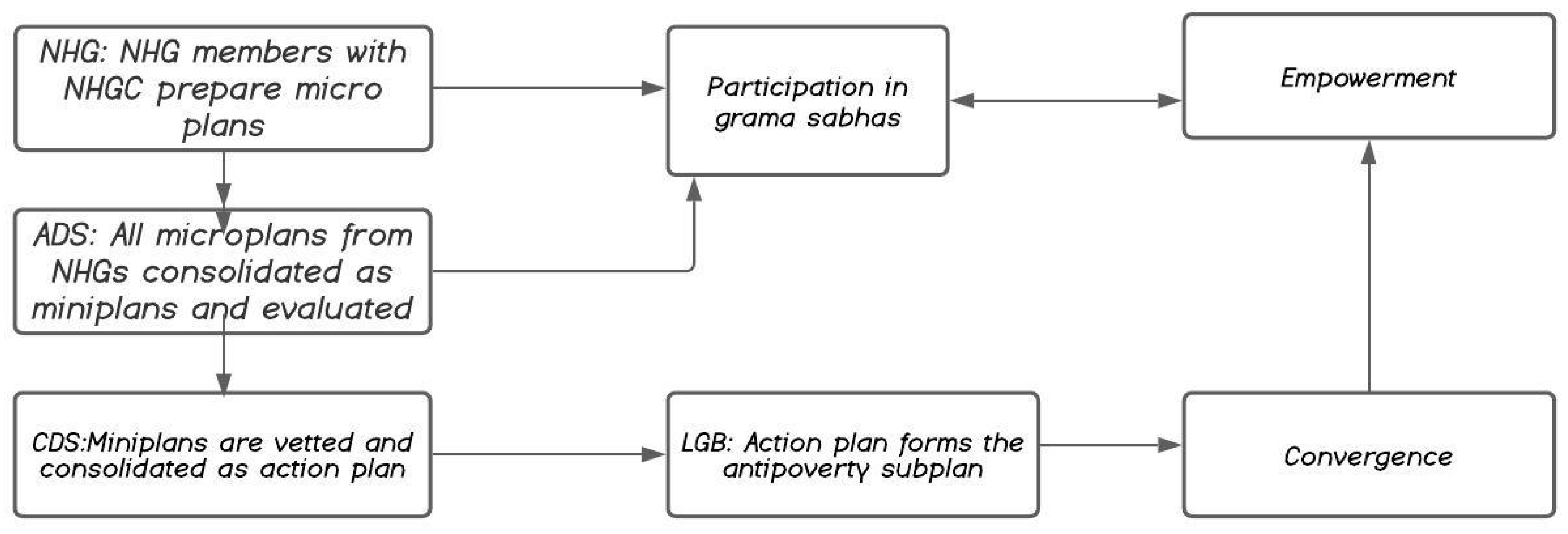

4.3.4. Convergence between Different Actors and Programmes

4.4. Micro-Enterprises: Key to Empowerment

4.5. Economic, Financial and Social Pillars of Empowerment

4.6. Multi-Actor Engagement Model for Successful Empowerment

4.7. Ownership-Role of the State Government for Women Empowerment

4.8. Decentralization of Decision Making in Favor of Local Governance and the Creation of Open Participation Spaces

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adjei, Stephen B. 2015. Assessing women empowerment in Africa: A critical review of the challenges of the gender empowerment measure of the UNDP. Psychology and Developing Societies 27: 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dajani, Haya, and Susan Marlow. 2013. Empowerment and entrepreneurship: A theoretical framework. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research 19: 503. [Google Scholar]

- Alsop, Ruth, Mette Bertelsen, and Jeremy Holland. 2005. Empowerment in Practice: From Analysis to Implementation. Washington: The World Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Alistair R., and Monica D. Lent. 2017. Enterprising the rural: Creating a social value chain. Journal of Rural Studies 70: 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, Shoba, Thankom Arun, and Usha Devi. 2011. Transforming livelihoods and assets through participatory approaches: The Kudumbashree in Kerala, India. International Journal of Public Administration 34: 171–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asian Development Bank. 2015. Gender Mainstreaming Case Study India. Kerala Urban Sustainable Development Project. Available online: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/160695/gender-mainstreaming-ind-kerala-urban.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Avelino, Flor, and Julia M. Wittmayer. 2016. Shifting power relations in sustainability transitions: A multi-actor perspective. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 18: 628–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bandhyopadhyay, D., B.N. Yugandhar, and Amitava Mukherjee. 2002. Convergence of programmes by empowering SHGs and PRIs. Economic & Political Weekly 37: 2556–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bastian, Bettina L. 2017. Empowerment Against All Odds: Women Entrepreneurs in the Middle East and North Africa. In Entrepreneurship: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 1975–87. [Google Scholar]

- Bastian, Bettina, and Mohammad Reza Zali. 2016. The impact of institutional quality on social networks and performance of entrepreneurs. Small Enterprise Research 23: 151–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, Bettina L., Beverly D. Metcalfe, and Mohamad R. Zali. 2019. Gender Inequality: Entrepreneurship Development in the MENA Region. Sustainability 11: 6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batliwala, Srilatha. 1994. The meaning of women’s empowerment: New concepts from action. In Population Policies Reconsidered: Health, Empowerment and Rights. Edited by Gita Sen, Adrienne Germain and Lincoln C. Chen. Harvard: Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Batliwala, Srilatha. 2007. Taking the power out of empowerment—An experiential account. Development in Practice 17: 557–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, Candida G., Anne De Bruin, and Frederieke Welter. 2009. A gender-aware framework for women’s entrepreneurship. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 1: 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calas, Marta B., Linda Smircich, and Kristina A. Bourne. 2009. Extending the boundaries: Reframing “entrepreneurship as social change” through feminist perspectives. Academy of Management Review 34: 552–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Census. 2011. Census Population Extrapolated; New Delhi: Government of India.

- Chesney, Barbara K., and Mark A. Chesler. 1993. Activism through self-help group membership: Reported life changes of parents of children with cancer. Small Group Research 24: 258–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craps, Marc, Inge Vermeesch, Art Dewulf, Koen Sips, Katrien Termeer, and René Bouwen. 2019. A relational approach to leadership for multi-actor governance. Administrative Sciences 9: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, Punita Bhatt, and Robert Gailey. 2012. Empowering women through social entrepreneurship: Case study of a women’s cooperative in India. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36: 569–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Chaux, Marlen, Helen Haugh, and Royston Greenwood. 2018. Organizing refugee camps: “Respected space” and “listening posts”. Academy of Management Discoveries 4: 155–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devika, J., and Binitha. V. Thampi. 2007. Between ‘Empowerment’ and ‘Liberation’: The Kudumbashree Initiative in Kerala. Indian Journal of Gender Studies 14: 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreze, Jean, and Amartya Sen. 1995. India: Economic Development and Social Opportunity. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dreze, Jean, and Amartya Sen. 2013. An Uncertain Glory: India and Its Contradictions. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duflo, Esther. 2012. Women Empowerment and Economic Development. Journal of Economic Literature 50: 1051–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, Crystal A. 2019. The gendered complexities of promoting female entrepreneurship in the Gulf. New Political Economy 24: 365–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, Arturo. 1992. Imagining a post-development era? Critical thought, development and social movements. Social Text 31/32: 20–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firstpost. 2021. The Promised Land: Kerala’s Female Emigrants Key Reason Behind Rise in Remittances. Available online: https://www.firstpost.com/long-reads/the-promised-land-keralas-female-emigrants-key-reason-behind-rise-in-remittances-3730831.html (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Franke, Richard. 1993. Life Is a Little Better: Redistribution as Development in an Indian State. Boulder: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaventa, John. 2006. Finding the spaces for change: A power analysis. IDS Bulletin 37: 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOK. 2021. Economic Review 2020–21; Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala: State Planning Board, vol. 1, p. 718. Available online: https://spb.kerala.gov.in/economic-review/ER2020/ (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Gopalan, S., R. Bhupathy, and H. Raja. 1995. Appraisal of Success Factors in Nutrition Relevant Programs: A Case Study of Alappuzha Community-Based Nutrition Programme. Chennai: United Nations Children’s Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Hooghe, Liesbet, Gary Marks, and Arjan H. Schakel. 2020. Multilevel governance. Comparative Politics 5: 193–210. [Google Scholar]

- India Planning Commission. 2008. Kerala Development Report. Cambridge: Academic Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Isaac, Thomas. 2001. Campaign for democratic decentralisation in Kerala. Social Scientist 29: 8–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, Maddy, and Jeanne M. Brett. 2006. Cultural intelligence in global teams: A fusion model of collaboration. Group & Organization Management 31: 124–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer, Naila. 1999. Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change 30: 435–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, Naila. 2005. Gender equality and women’s empowerment: A critical analysis of the third millennium development goals. Gender and Development 13: 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadiyala, Suneetha. 2004. Scaling up Kudumbashree Collective Action for Poverty Alleviation and women’s Empowerment. Washington: International Food Policy Research Institute USA, May. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan, K.P. 1999. Rural Labour Relations and Development Dilemmas in Kerala: Reflections on the Dilemmas of a Socially Transforming Labour Force in a Slowly Growing Economy. Journal of Peasant Studies 26: 140–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, K.P., and G. Raveendran. 2017. Poverty, Women and Capability: A Study of the Impact of Kerala’s Kudumbashree System on Its Members and Their Families. Thiruvananthapuram: Laurie Baker Centre for Habitat Studies. Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiYxrDxorbvAhWjyYsBHR1jA4AQFjAAegQIARAD&url=http%3A%2F%2Fkudumbashree.org%2Fstorage%2Ffiles%2F1yzdo_kshree%2520full%2520ms_kpkcorrected%2520with%2520cover_08.11.17-1.pdf&usg=AOvVaw3F9x64beqIf8ACBSDLMq7b (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Knüppe, Kathrin, and Claudia Pahl-Wostl. 2013. Requirements for adaptive governance of groundwater ecosystem services: Insights from Sandveld (South Africa), Upper Guadiana (Spain) and Spree (Germany). Regional Environmental Change 13: 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudumbashree. 2019. Annual Plan 2019-20. Available online: https://kudumbashree.org/pages/765 (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Kudumbashree. 2020. Kerala State Rural Livelihood Mission Day NRLM Annual Action Plan 2019–2020. Available online: qm0dp_kudumbashree nrlm aap 2019-20.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Kudumbashree. 2021. Kudumbashree. Available online: https://www.kudumbashree.org/ (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Kudumbashree-NRO. 2014. Imagining Convergence Kerala Context & an Ideation Framework. Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala: Kudumbashree-National Resource Organization, August, 21p, Available online: https://www.kudumbashreenro.org/resources/others/item/download/3_5f92507e2512b59aded65d53ca6cf9ce (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Kusters, Koen, Louise Buck, Maartje de Graaf, Peter Minang, Cora van Oosten, and Roderick Zagt. 2018. Participatory planning, monitoring and evaluation of multi-stakeholder platforms in integrated landscape initiatives. Environmental Management 62: 170–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mair, Johanna, Ignasi Marti, and Marc J. Ventresca. 2012. Building inclusive markets in rural Bangladesh: How intermediaries work institutional voids. Academy of Management Journal 55: 819–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, Anju, Sidney Ruth Schuler, and Carol Boender. 2002. Measuring Women’s Empowerment as A Variable in International Development. Washington: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, Matthew B., and A. Michael Huberman. 1984. Drawing valid meaning from qualitative data: Toward a shared craft. Educational Researcher 13: 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosedale, Sara. 2005. Assessing women’s empowerment: Towards a conceptual framework. Journal of International Development 17: 243–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, Swapna, ed. 2007. The Enigma of the Kerala Woman: A Failed Promise of Literacy. New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Muntean, Susan C., and Banu Ozkazanc-Pan. 2016. Feminist perspectives on social entrepreneurship: Critique and new directions. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 3: 221–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan-Parker, Deepa, ed. 2005. Measuring Empowerment: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives. World Bank Publications: Available online: worldbank.org (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Nawaz, Faraha. 2019. Microfinance and Women’s Empowerment in Bangladesh: Unpacking the Untold Narratives. London: PalgraveMacmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Nithya, N.R. 2013. Land question and the tribals of Kerala. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research 2: 102–5. Available online: http://www.ijstr.org/final-print/sep2013/Land-Question-And-The-Tribals-Of-Kerala.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Ojediran, Funmi O., and Alistair Anderson. 2020. Women’s Entrepreneurship in the Global South: Empowering and Emancipating? Administrative Sciences 10: 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parwez, Shazzad. 2016. A Comparative Study of Gujarat and Kerala Developmental Experiences. International Journal of Rural Management 12: 104–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratto, Felicia. 2016. On power and empowerment. British Journal of Social Psychology 55: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghavan, V.P. 2009. Micro-credit and Empowerment: A study of Kudumbashree Projects in Kerala, India. Journal of Rural Development 28: 478–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rajan, S. Irudaya. 2004. From Kerala to the Gulf: Impacts of Labor Migration. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 13: 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reheem, S. 2013. A case study on Kudumbashree: Political empowerment of women for sustainable poverty reduction. International Journal of Sustainability in Economic, Social, and Cultural Context 8: 121–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, Marilyn, and Trevor Hancock. 2016. Equity, sustainability and governance in urban settings. Global Health Promotion 23: 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, Jo. 1995. Empowerment examined. Development in Practice 5: 101–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowlands, Jo. 2016. Power in practice: Bringing Understandings and Analysis of power into Development Action in Oxfam. Institute of Development Studies. Available online: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/12663 (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Sachana, P.C., and A. Anilkumar. 2015. Differential perception of livelihood issues of tribal women: The case of Attappadi the state in Kerala. India. International Journal of Applied and Pure Science and Agriculture 1: 124–28. [Google Scholar]

- Santhosh, Kumar S. 2012. Capacity building through women groups. Journal of Rural Development 31: 235–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal, P. 2009. From credit to collective action: The role of microfinance in promoting women’s social capital and normative influence. American Sociological Review 74: 529–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saradamoni, K. 1999. Matriliny Transformed. New Delhi: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, Donald, and Chris Argyris. 1996. Organizational Learning II: Theory, Method and Practice. Reading: Addison Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Selvi, S.C., and K.S. Pushpa. 2018. Factors influencing on rural women empowerment of Kudumbashree programme. International Journal of Current Advanced Research 7: 9220–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Amartya. 1999. Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Siwal, Beg Raj. 2009. Gender Framework Analysis of Empowerment of Women: A Case Study of Kudumbashree Programme. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1334478 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Tasan-Kok, Tuna, and Jan Vranken. 2008. From survival to competition? The socio-spatial evolution of Turkish immigrant entrepreneurs in Antwerp. Geojournal Library 93: 151. [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe, Jodie, and John Gaventa. 2020. Democratising Economic Power: The Potential for Meaningful Participation in Economic Governance and Decision-Making. IDS. Available online: ids.ac.uk (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- UNDP. 2018. Gender Equality Strategy 2018–2021. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/womens-empowerment/undp-gender-equality-strategy-2018-2021.html (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- UNICEF. 2021. The State of the World’s Children. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/reports/state-of-worlds-children (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Vangen, Siv, John Paul Hayes, and Chris Cornforth. 2015. Governing cross-sector, inter-organizational collaborations. Public Management Review 17: 1237–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, M. 2012. Women Empowerment through Kudumbasree: A Study in Ernakulam District. Available online: https://shodhgangotri.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/123456789/777/1/synopsis.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Venugopalan, K. 2014. Influence of Kudumbasree on Women Empowerment–a Study. IOSR Journal of Business and Management 16: 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véron, Rene. 2001. The “new” Kerala model: Lessons for sustainable development. World Development 29: 601–17. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan, P. K., and Amita Shah. 2016. Gender Impact of Trade Reforms in India: An Analysis of Tea and Rubber Production Sectors. In Globalisation, Development and Plantation Labour in India. Edited by K.J. Joseph and P.K. Viswanathan. London: Routledge, New Delhi: Routledge India (South Asia Edition), pp. 234–65. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan, P. K., and Varachai Thongthai. 2009. Gender Differences in Educational Attainments and Occupational Status in Thailand: A study based on Kanchanaburi DSS Data. Journal of Population and Social Studies 17: 83–122. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, Jeroen. 2005. Multi-stakeholder platforms: Integrating society in water resource management? Ambiente & Sociedade 8: 4–28. [Google Scholar]

- Welter, Frederike, Baker Ted, and Wirsching Katharine. 2019. Three waves and counting: The rising tide of contextualization in entrepreneurship research. Small Business Economics 52: 319–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Glyn, Binitha V. Thampi, D. Narayana, Sailaja Nandigama, and Dwaipayan Bhattacharyya. 2011. Performing Participatory Citizenship—Politics and Power in Kerala’s Kudumbashree Programme. Journal of Development Studies 48: 1261–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Bronwyn P., Poh Yen Ng, and Bettina Lynda Bastian. 2021. Hegemonic Conceptualizations of Empowerment in Entrepreneurship and Their Suitability for Collective Contexts. Administrative Sciences 11: 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Robert K. 2014. Case Study Research Design and Methods, 5th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

| Date | Milestones & Description |

|---|---|

| 1991 | Government of Kerala launched a community-based nutrition program (CBNP): Objective was to improve nutritional levels of children and women. |

| 1993 | Establishment of community development society (CDS) system at Alappuzha and Malappuram: Alappuzha Municipality established CDS in 1993. National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) agrees to refinance bank loans to NHGs. CDS system was formed in 94 Gram Panchayats and five Municipalities in Malappuram district. |

| 1994 | Alappuzha Model extended to all five Municipalities and 94 Village Panchayats in Malappuram district. |

| 1995 | The CDS network was extended to cover all 58 Municipalities in the state. |

| 1996 | The Ministry led by the Left Democratic Front (LDF) launches Peoples Plan Campaign in Kerala that triggers people participation in local development process. |

| 1997 | A Task Force of the Government presents a report to extend the Alappuzha Model to the entire State under the name, Kudumbashree |

| 1998 | State Poverty Eradication Mission (SPEM) registered under the Travancore-Cochin Literary, Scientific and Charitable Societies Act 1955. Thus, Kudumbashree Mission becomes a legal entity in the state. |

| 1999 | State Urban Poverty Alleviation (UPA) Cell wound up; SPEM declared State Urban Development Agency (SUDA). Kudumbashree Mission becomes the nodal agency for urban poverty alleviation projects. |

| 2000 | Kudumbashree Mission Office set up in June and chalks out a 3-phase plan to form Kudumbashree CDSs in all Panchayats (based on NHGs). CDS system extended to 262 Gram Panchayats, which were selected based on their performance in the People’s Plan campaign. |

| Initiates training and other assistance schemes for starting Micro Enterprises by Kudumbashree women | |

| 2001 | The new government led by the United Democratic Front (UDF) assumes office. CDS system further expanded to cover 338 more Gram Panchayats, along with new guidelines. |

| 2002 | CDS system launched in 291 more Gram Panchayats. Kudumbashree assists the government in identifying beneficiaries under its Ashraya Scheme (care of the destitutes). |

| 2003 | CDS system was extended to cover the entire state of Kerala. Joint Liability Groups (JLGs) started to encourage Kudumbashree women’s groups to take up agriculture in leased in land. |

| 2005 | Government takes major policy decisions: (a) Implementation of the NREGS only through Kudumbashree; (b) Formation of exclusive SC and ST NHGs wherever feasible. |

| 2005 | (a) State launches national rural employment guarantee scheme (NREGS); (b) Promotes Bala Sabhas of Kudumbashree children; (c) Micro Enterprises formed to supply nutritional food to all ICDS centres; (d) Initiates setting up of BUDS Schools. |

| 2006 | New government led by LDF assumes office. Kudumbashree women demands more autonomy and elections at all levels, i.e., NHG’s; ADS; CDS) |

| 2007 | State government issues orders integrating SHGs under Swarnajayanthi Gram Sswarozgar Yojana (SGSY) with Kudumbashree. End of dual membership of poor families in SGSY SHGs and Kudumbashree NHGs. |

| 2008 | Kudumbashree adopts Common Bye-Law for all CBOs. First election of Kudumbashree office bearers takes place. Launches Gender mainstreaming and Integration programmes. |

| 2011 | UDF forms a new Government. Kudumbashree holds the Second election of office bearers for CBOs. |

| 2013 | National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM) selects Kudumbashree as its state level nodal agency. |

| 2014 | Revised Election Guidelines: Secret ballot system replaces election through consensus at the general body meetings of the community organisation. Third election of office bearers within the Kudumbashree CBOs |

| 2016 | LDF forms new government in the state. |

| 2017 | Kudumbashree Mission starts to work with Haritha Karma Sena Project based on government order (GO number: 2420/2017-LSGD). This along with Suchitwa Mission and Clean Kerala Company work towards a garbage-free Kerala. The powers to select Haritha Keralam Sena are vested with the local bodies. |

| 2019–2020 | Kudumbashree focused on formation of special NHGs for addressing the specific needs of vulnerable communities/groups. 15,794 elderly NHGs (1.8 lakh members), 11 transgender NHGs (128 members) and 1610 NHGs (13,077 members) for persons with disability (PWD)were formed till 30th September 2019. |

| Physical Components | No/Quantity * |

|---|---|

| 1. No of NHGs | 2,87,723 |

| 2. No. of NHG Members | 4,51,0000 |

| 3. Transgender groups (Nos.) | 19 |

| 4. Differently abled (disabled) Person Groups | 754 |

| 5. Elderly Groups (Nos) | 2123 |

| 6. Women Micro Enterprises (Nos) | 87,239 |

| 7. No of JLGs | 71,572 |

| 8. No of JLG members | 3,54,122 |

| 9. Women JLGs (agriculture) | 50,620 |

| 10. Lease Land Farming (Hectares) | 43,744 |

| 11. Ashraya Destitute Rehabilitation project (no of families) | 174,443 |

| 12. BUDS schools (for mentally challenged students) | 3 |

| 13. Tailoring units | 359 |

| 14. IT Units & Survey Team# | 63 |

| 15. Railways (Parking and Waiting hall management) | 40 Stations |

| 16. Metro station management (Nos.) * | 70 |

| 17. Vulnerability mapping done (No of Panchayats) | 140 |

| Component | Amount (Rs. Million) * | (%) Share |

|---|---|---|

| I. Social Development & Empowerment | ||

| (a) Destitute Free Kerala | 514.04 | 46.19 |

| (b) BUDs | 18.65 | 1.68 |

| (c) Balasabha | 2.26 | 0.20 |

| (e) Gender Education and women empowerment | 27.15 | 2.44 |

| (f) Tribal Development | 15.98 | 1.44 |

| Sub Total | 578.08 | 51.95 |

| II. Local Economic Development & Empowerment | 0.00 | |

| (a) Microfinance | 359.14 | 32.27 |

| (b) Micro Enterprise Activities | 18.22 | 1.64 |

| (c) Agricultural Activities | 124.82 | 11.22 |

| (d) Animal Husbandry activities | 19.19 | 1.72 |

| (e) Marketing development | 13.32 | 1.20 |

| Sub Total | 534.69 | 48.05 |

| Grand total | 1112.78 | 100.00 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Venugopalan, M.; Bastian, B.L.; Viswanathan, P.K. The Role of Multi-Actor Engagement for Women’s Empowerment and Entrepreneurship in Kerala, India. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11010031

Venugopalan M, Bastian BL, Viswanathan PK. The Role of Multi-Actor Engagement for Women’s Empowerment and Entrepreneurship in Kerala, India. Administrative Sciences. 2021; 11(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleVenugopalan, Murale, Bettina Lynda Bastian, and P. K. Viswanathan. 2021. "The Role of Multi-Actor Engagement for Women’s Empowerment and Entrepreneurship in Kerala, India" Administrative Sciences 11, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11010031

APA StyleVenugopalan, M., Bastian, B. L., & Viswanathan, P. K. (2021). The Role of Multi-Actor Engagement for Women’s Empowerment and Entrepreneurship in Kerala, India. Administrative Sciences, 11(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11010031