1. Introduction

The concept of core competencies was introduced to the scientific discussion in 1990 by C. K. Prahalad and G. Hamel (

Prahalad and Hamel 1990). Since then, it has gained much attention in the world management literature. The precursors understood core competencies as “the collective learning in the organization, especially how to coordinate diverse production skills and integrate multiple streams of technologies.” As they indicate in their work, core competence does not diminish with use, unlike physical assets, which do deteriorate over time—they are enhanced as they are applied and shared (

Prahalad and Hamel 1990). According to Petts (

Petts 1997), core competencies are a unique combination of technologies, knowledge, and skills that are possessed by one company in a market. Referring in turn to Grønhaug and Nordhaug, core competence is what a firm is able to perform with excellence compared to its competitors (

Grønhaug and Nordhaug 1992). Core competencies define the shape of a company’s operations, including how effectively its strategic objectives are achieved.

It should be stressed that the core competencies are the product of the organization’s intangible resources, which include, in particular, the company’s knowledge and capabilities. Imitation of the core competencies is significantly impeded or even impossible, thanks to which they gain permanent character. In discussing this relationship, causal ambiguity must be taken into account. It refers to situations where the causal link is not obvious. Two types of causal ambiguity can be distinguished—characteristic ambiguity and linkage ambiguity. The first one refers to the characteristics of the resource itself. The second is understood as the ambiguity of the relationship between resources and competitive advantages (

King and Zeithaml 2001). If both the company’s managers and its competitors do not fully understand the reasons for its competitive advantage, this advantage is likely to be maintained as it will not be copied (

Ambrosini and Bowman 2010). On the other hand, causal ambiguity makes it difficult for a company to learn from its own experience and improve its performance over time (

McEvily et al. 2000). Consequently, when causal ambiguity is reduced, it can also erode a company’s performance.

According to the concept of core competencies, competitive advantage is based on the ability to build core competencies at lower cost and faster than competitors to generate new and improved products and services. In other words, the real source of competitive advantage is the ability of managers to consolidate across the entire corporation, production technologies, and skills, and translate them into competencies that will allow specific business units to adapt quickly to changing opportunities (

Haffer 2003, p. 69).

The concept of dynamic capabilities, as well as the concept of core competencies, extends the resource-based theory. It directs the research interest to the role of changes taking place in the business environment and the problem of the organization adapting to them in order to develop and maintain competitive advantages. The scientific discourse was started by D. J. Teece, G. Pisano, and A. Shuen in 1990 (

Teece et al. 1990). At that time, the authors pointed out the importance not only of a specific bundle of resources, but also of mechanisms through which enterprises learn and accumulate new abilities and forces that limit the pace and direction of realized processes. Hence, there is a clear suggestion to change the way the strategic situation of enterprises is analysed. The authors presented a complete concept model in 1997 (

Teece et al. 1997). Since then, interest in the issues in management science has been constantly growing.

According to C.E. Helfat et al., dynamic capability is the capacity of an organization to purposefully create, extend, or modify its resource base (

Helfat et al. 2007). This definition, in my opinion, accurately reflects the essence of the problem. Presently, interest in the issues, including, among others, opportunities to operationalize dynamic capabilities, has been growing intensely. Dynamic capabilities can take a variety of forms and involve different functions, such as marketing, product development, or process development (

Easterby-Smith et al. 2009, pp. S6–S7). There is no obstacle to overlap between the categories of core competencies and dynamic capabilities in a specific case, i.e., that a core competence meets all the characteristics of a dynamic capability, and vice versa.

For analytical purposes, the proposal made by D. J. Teece in 2007 (

Teece 2007,

2018) was applied, according to which dynamic capabilities are divided into three groups, i.e., sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring. It can be perfectly used for empirical research, including case study. Dynamic capabilities allow to identify a need or a chance for change, to prepare a way of responding to these needs and opportunities, and to implement an appropriate course of action or take the right direction. However, it should be borne in mind that not all dynamic capabilities serve the three functions (

Helfat et al. 2007).

“Sensing” includes the acquisition of knowledge about the external and internal environment for strategic decision-making. In other words, it is a set of dynamic capabilities that includes gaining knowledge about competitors, exploring new technological opportunities, researching markets, listening to customers and suppliers, and exploring other elements of the business system. Through systematic use of identification activities, companies can discover new and significant opportunities, reveal latent demand, discover early moves by both suppliers and competitors, and identify risks in a timely manner (

Wilhelm et al. 2015). “Seizing” involves mobilizing and inspiring organizations to develop a readiness to take the opportunities and reduce risk. Among the key activities within its framework, one can point out, among others, drawing up a business analysis and communicating it, raising capital, planning the implementation of the strategy, and implementing innovative business models (

Feiler and Teece 2014). “Reconfiguring” refers to procedures designed to maintain the company’s strategic importance in changing markets by continuously modifying its tangible and intangible resources (

Feiler and Teece 2014).

Strategic intangible resources, among them capabilities and dynamic capabilities, which determine the creation of core competencies, according to the resource-based theory, should meet a number of features. Among them it is indicated that resources may become a source of competitive advantage to the degree that they are scarce, specialized, appropriable (

Amit and Schoemaker 1993), valuable, rare, imperfectly imitable, and have no strategic equivalents (

Barney 1991;

Cegliński 2016), complexity, invisibility, durability, and appropriability (

Petts 1997). Therefore, the literature points to the great difficulty of developing core competencies (

Ljungquist 2007).

2. Research Methodology

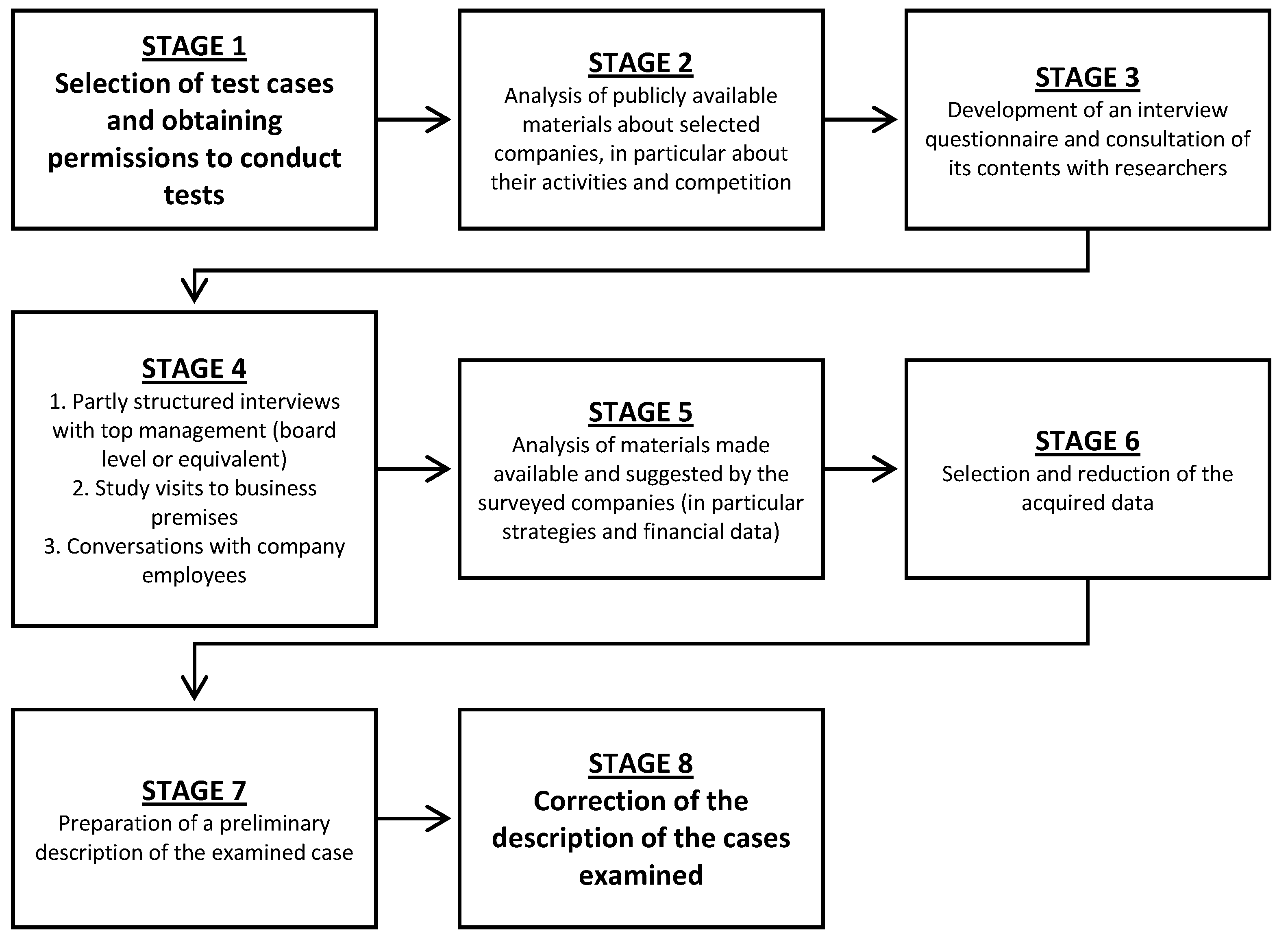

This part of the article presents the methodology of empirical research, the aim of which is to check the assumed relationship between dynamic capabilities, core competencies, and core and end products/services of companies (see

Figure 1). It was assumed that dynamic capabilities, as naturally associated with change at the strategic level, are the category starting the relationship. Core and end products are a tangible reflection of intangible core competencies (see also:

Hamel and Heene 1994;

Prahalad and Hamel 1990). The cases of the Panek S.A. and Cukiernia Sowa companies were examined. The main reasons for the choice are the size of both entities, above-average rate of development, and intensity of competition and competitive position allowing to assume that these organizations are leaders in their industries. It should be stressed that the companies invited to research were selected in such a way as to have as few similarities as possible between them, and thus to maximise the scope of potential research aspects. What these entities have in common is that they have developed long sustainable competitive advantages by dealing with negative and turbulent changes in the environment.

It should be stressed that the case study does not, in principle, serve to empirically test the conceptual model and formulate generalised conclusions, but provides a practical example that allows for a thorough understanding of a specific issue. Case studies are widely used in research. Among other things, they can support creating theory (

Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007;

Eisenhardt 1989;

Gersick 1988;

Pinfield 1986;

Kidder 1982). A case study is always set in a specific unique context, but this does not seem to allow for its depreciation (

Miles 2015;

Thomas 2010;

Flyvbjerg 2006). Research of this kind seems to be suitable for understanding the subtle phenomenon of creating and renewing resources, abilities, and competencies of a company. It should be remembered that the issue of strategic management is a complex phenomenon, almost always individualised for the needs of a particular entity. An obvious limitation of the case study method is the subjectivity of the researcher (limited by the proper research methodology), difficulty in repeating the research and being time-consuming.

After obtaining permissions to participate in the survey, the publicly available materials were carefully analysed, including the use of company websites, industry portals, and press articles about them. In a third stage, an interview questionnaire was developed. This instrument gave direction to the interviews, but some of them were necessarily unstructured, which is natural for this type of research. It is impossible to predict what answers will be given and what specific aspects will be addressed by the respondents. At stage four, a number of interviews were conducted with the management of selected companies, followed by the analysis of materials made available by them (stage five). It should be noted that the interviews had to correspond to the adopted procedure for the identification of core competencies. At stage 6, the first version of the text was prepared, while at stage 7, this content was consulted and corrected.

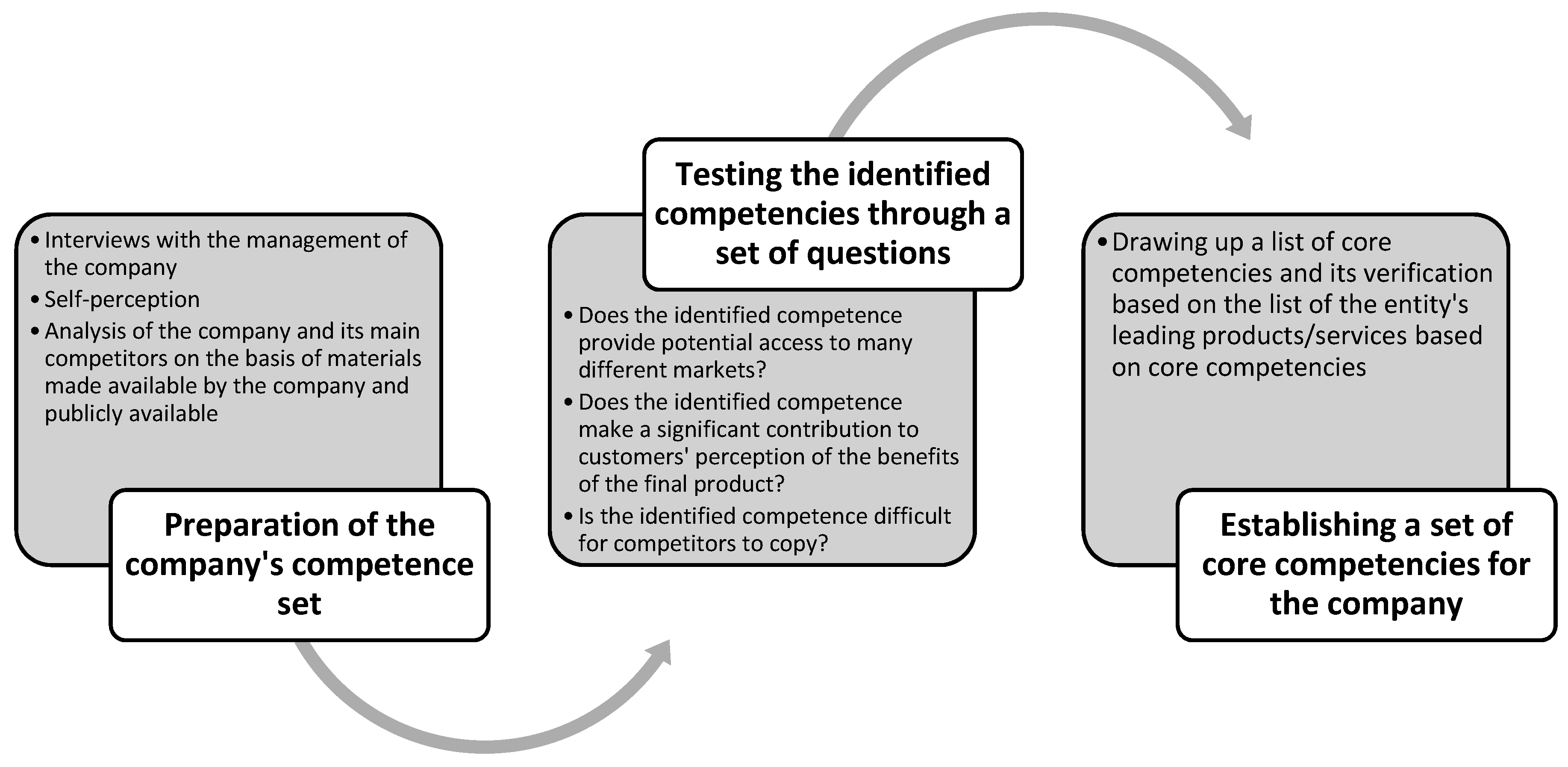

Within the framework presented in

Figure 2, a data analysis procedure consisting of three stages was adopted to identify the core competencies of the entities examined (

Figure 3; see also:

Siqueira and Bremer 2000). During the first stage, a set of competencies of the surveyed company was prepared. At this stage, care was taken to ensure that the indicated competencies were not assessed in any way, regardless of the source of the indication, including interviews with the managerial staff, author’s own observation (as part of study visits), and analysis of the company, its competitors, and their environment on the basis of available and publicly available materials, in particular, company reports including profit and loss accounts and annual balance sheets, internal studies, descriptions of organizational structures, promotional documents, press articles, and industry studies. In the second stage, it was verified whether and which of the identified competencies are core competencies. For this purpose, the test proposed by C. K. Prahalad and G. Hamel was used with a slight modification, which is based on three questions (

Prahalad and Hamel 1990):

- (1)

Does the identified competence provide potential access to many different markets?

- (2)

Does the identified competence make a significant contribution to customers’ perception of the benefits of the final product?

- (3)

Is the identified competence difficult for competitors to copy?

The three positive answers allow us to suppose, but not to be certain, that the examined competence of the company is a core competence, i.e., the one that significantly translates into the nature and competitiveness of the final product/service. Companies with above-average market success base their business on a few, not a dozen or a several dozen competencies. It should also be remembered that core competencies are not static categories, they are subject to both erosion and evolution, also without direct intervention of management. Similarly to dynamic capabilities, in order to maintain their positive impact on the business, enterprises should be constantly developed and modified. It is often advisable to work on new competencies, among other things, in a situation of major technological changes affecting the shape of industries and markets. As the third stage of the procedure, a final list of core competencies was prepared, which was additionally verified by analysing the leading products/services of the companies. The developed set of core competencies was juxtaposed with the identified components of the dynamic capabilities of the surveyed companies and assigned to individual categories.

3. Research Results

3.1. Panek S.A. Case Study

Panek S.A. is the leader of the Polish car rental industry. Its offer includes over 2000 cars in over 60 rental points in Poland and Lithuania. The company’s services are divided into short-, medium-, and long-term rental, rental from the offender’s liability insurance, and car rental for corporates. Moreover, since 2017, the offer has been complemented by the PANEK CarSharing service, which makes it possible to rent a car for minutes. The use of the system is based on the PANEKcs application designed for mobile devices, especially smartphones. With the help of this application, cars are searched, booked, and opened. It is worth pointing out that the users of cars as part of the sharing service benefit from a number of facilities, including no charges for parking in the paid parking zones in Warsaw and Lublin. Panek S.A. has won many industry awards. The more important ones include Fleet Awards in the “Best Short Term Rental” category and Fleet Derby in the “Best Fleet Service—Short Term Rental” category.

The company builds and bases its ability to adapt to the business environment on shortening the decision-making process to an absolute minimum. Such a system is part of the organizational culture developed in the company over the years. A relatively flat organizational structure allows for immediate information transfer directly to managers at all levels.

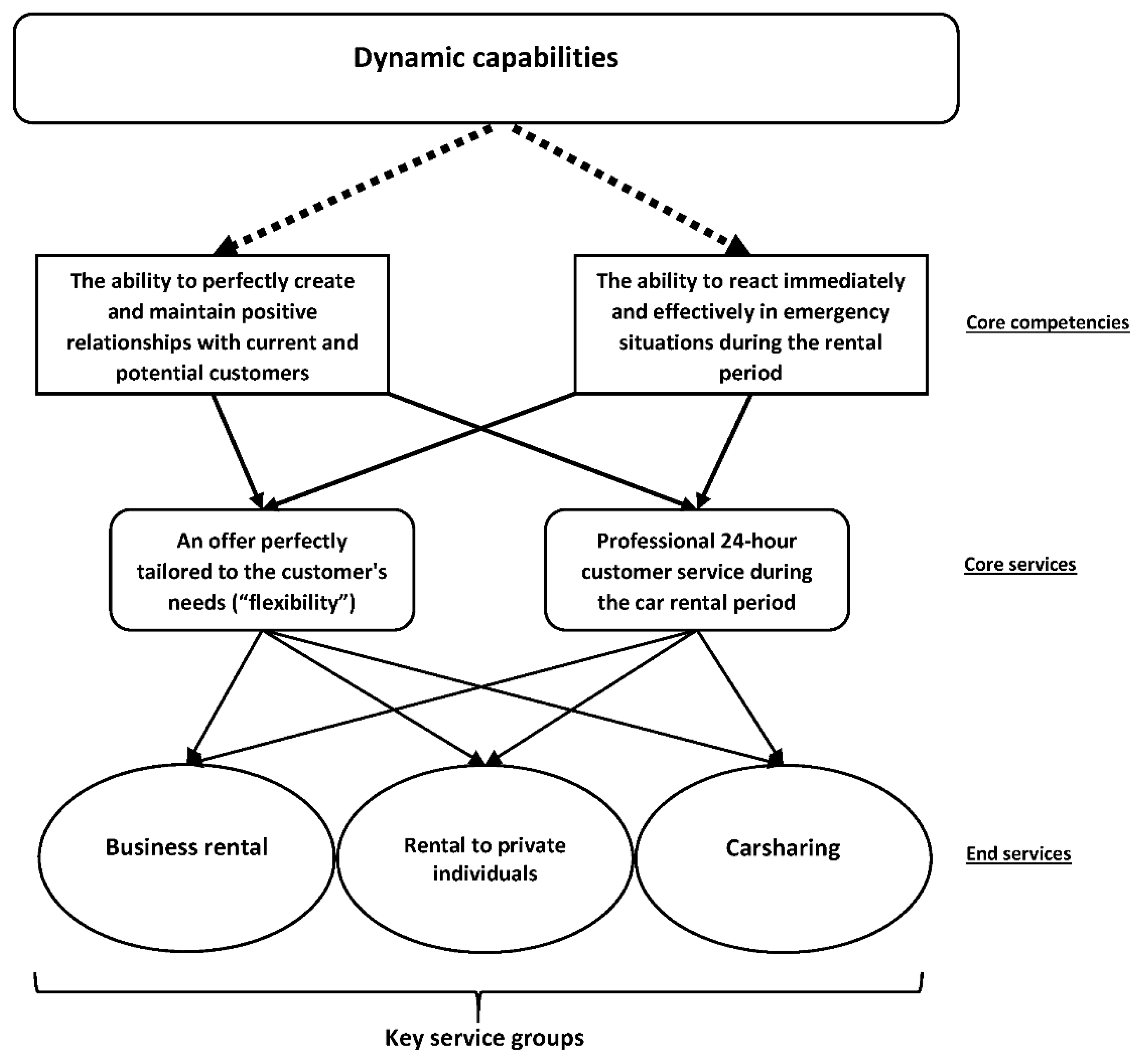

The identified core competencies of Panek S.A. are:

- -

the ability to perfectly create and maintain positive relations with current and potential customers before, during, and after the service provided;

- -

the ability to react immediately and effectively in emergency situations.

Both core competencies are reflected in the company’s services. It should be noted that a car rental service does not only consist of the vehicle itself, which is material and standardized, so it can be easily copied. The ownership of these resources by any other entity depends solely on its financial resources. As previously indicated, a sustainable competitive advantage cannot be built on a resource that is easily copied. Therefore, intangible elements accompanying the rental are decisive for the competitive position (see

Figure 4).

The core competencies of Panek S.A. are modified with the use of dynamic capabilities. The ability to perfectly create and maintain positive relations with current and potential customers (at each stage of the service provided, as well as before and after its performance) is shaped in particular by the following dynamic capabilities:

- (1)

the capability to adapt quickly to customers’ needs (“seizing”);

- (2)

the capability to shorten decision-making processes (“reconfiguring”);

- (3)

the capability to take risks and pro-innovative actions (“seizing”).

The ability to react immediately and effectively in crisis situations is shaped in particular by:

- (1)

the capability to create excellent working conditions for all employees (“sensing”/”seizing”);

- (2)

the capability to provide an almost unlimited circulation of information and knowledge within the enterprise (“sensing”/“seizing”).

The success of Panek S.A. is based on constant adaptation to the customer’s needs, searching for innovative solutions and taking care of the work comfort of the entire staff. These assumptions are the basis for a meticulously implemented business strategy of the company.

3.2. Cukiernia Sowa Case Study

Cukiernia Sowa is one of the most valued and recognizable confectionery brands in Poland. In 1946, in a tenement house on Pomorska Street in Bydgoszcz, Feliks and Stanisława Sowa opened their first bakery. In 1952, the first employees were hired, followed by students and an apprentice. In 1962, based on the family recipe, the first flagship product was introduced. It was a chocolate cake—a sponge cake with fruit jam coated in milk chocolate. In 1982, the current owner, Adam Sowa, entered the family business. Six years later, in 1988, a second outlet was opened. At the end of 1997, the construction of a new production plant at Ks. Schulz Street began. At present, the residence of the Cukiernia Sowa is located there. This allowed for a dynamic increase in production capacity, which resulted in the opening of further points of sale. In 2005, international expansion began. Confectionery products are already available in London and Berlin, among others. In 2008, under the guidance of Parisian confectionery masters, Cukiernia Sowa developed its own proprietary chocolate brand. In 2009, Sowa Caffè, a coffee traditionally roasted in its own roasting plant, made from South and Central American Arabica beans, was introduced to the offer.

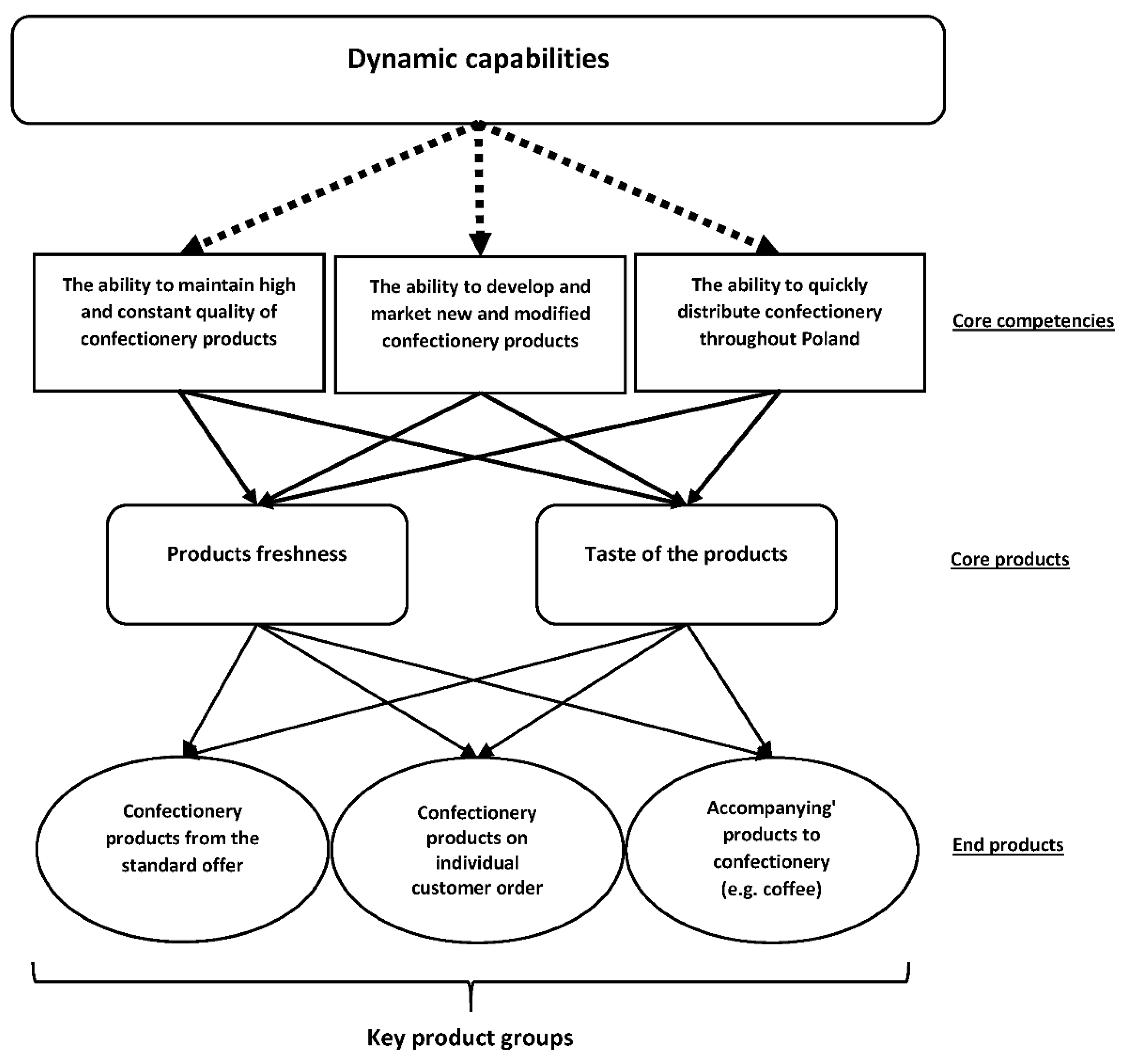

Due to the wide range of products and services offered, the focus is on confectionery products, i.e., the main branch of the company’s activity (see

Figure 5). Three core competencies were distinguished:

- -

the ability to maintain high and constant quality of confectionery products in mass production;

- -

the ability to quickly distribute confectionery products throughout Poland;

- -

the ability to develop and market new and modified confectionery products.

The following closely related dynamic capabilities of Cukiernia Sowa have been identified:

- (1)

the ability to react quickly to emerging opportunities and threats (“seizing”);

- (2)

the ability to maintain a relatively small distance of power within the company (“seizing”);

- (3)

the ability to search for and implement new product categories, respecting the core products (“sensing”/“reconfiguring”).

What is important, similarly as in the case of Panek S.A., is that the dynamic capabilities of Cukiernia Sowa have a great influence on the shape of core competencies and allow for their adaptation to the changing business reality. Due to the specific nature of the industry, the core competencies are subject to relatively fast depreciation, and without proper modification they would become useless.

First of all, the ability of the company to react quickly to opportunities and threats that arise should be indicated. Cukiernia Sowa is a family enterprise, built since 1946. Despite exceeding the employment level of 1000 people, the organization is still managed in a way that is considered to be specific to family businesses (

Gimeno et al. 2010). The partners do not limit their role in the company to office work and representation functions, which is allowed by the current shape and size of the company, as well as the competencies of the employees. In particular, as far as possible, the partners take care of the production process on their own and take an active part in the implementation of new organizational and assortment solutions.

The second ability that should be considered as dynamic is the ability to create and maintain a relatively small power distance in an enterprise (

Hofstede et al. 1990,

2011), which is based on the organizational culture formed in the enterprise. The result of this approach is a widespread openness to constructive criticism of each aspect of the company’s activities on the part of employees and excellent, non-formalised relationships between partners and lower-level management. In a large and complex company, where management is forced to make strategically important decisions almost every day, trust in employees plays an invaluable role. The process of building trust is long and requires from leaders, in addition to competence, kindness, justice, and openness (

Mayer et al. 1995;

Rudzewicz 2016).

The third of these capabilities is the near-perfect ability to find and implement new product categories. In the company, based on the passion for confectionery that has been passed on for years, great importance is attached to the constant search for new recipes and ways to improve the quality of the products offered. This aspect is the responsibility of both the partners themselves and, at least in principle, each of the employees. This is related to the openness outlined in the previous paragraphs and the relatively small distance of power in the company. The abovementioned abilities constitute the whole dynamic capabilities of Cukiernia Sowa, i.e., they make it possible to create and renew ordinary abilities, as a result of which they condition the maintenance of a sustainable competitive advantage and one of the strongest confectionery brands on the Polish market.

4. Conclusions

The obtained results of own research and the analysis of the literature on the subject indicate a positive relationship between the dynamic capabilities and core competencies of the company. Dynamic capabilities support the continuous modification of core competencies, which are reflected in core products and services, and ultimately also in the final products and services. In times of increasing complexity of the business environment, accelerating changes and increasingly limited possibilities to forecast them, adaptability may prove crucial, not only for achieving a sustainable competitive advantage in the sector, but even for the survival of the company. Both theory and practice indicate that dynamic capabilities and related core competencies are fundamental for adaptation to the business environment. They are, in principle, more durable than the vast majority of material and nonmaterial resources, difficult to copy by competitors, and are applied in many aspects of a company’s activity.

Based on the current scientific output in the undertaken research area, it is not possible to conduct a discussion that would be reliable from the point of view of the methodology of management sciences. Despite the large number of publications available in the field of dynamic capabilities and core competencies, there is a lack of content allowing for direct comparisons. Moreover, the empirical research carried out has been given the characteristics of exploratory research, i.e., research that is to a large extent only to help establish the directions of further in-depth empirical research. Similar studies have not been conducted in Poland so far or this fact has not been sufficiently documented in the literature.