Gender Diversity in Academic Sector—Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Gender is one of the aspects of diversity in organizations, and gender diversity deals with the equal representation of men and women in the workplace. A work-team is a social group within which people should work collectively to achieve a synergic effect (Seroka-Stolka 2016). Understanding the factors of the diversity in a work environment is crucial to underline the source of people’s behavior and to foresee its impact on collective work.

- The issue is important, as there are barriers for women in the labor market. In the European Union, the phenomenon of women’s presence on boards of directors has been present since 2010, when the European Commission introduced the “Strategy for equality between women and men 2010–2015”. One of its targets was to have 40 percent of women represented in committees and expert groups established by the Commission (European Commission 2011). Moreover, in November 2012, the Commission proposed another target of 40 per cent representation of women in the board of directors in stock-listed companies in Europe by 2020. Despite the policy in Western Europe, only 17 percent of executive-committee members are women, and women comprise just 32 percent of members of corporate boards for companies listed in Western Europe’s major market indexes (exhibit) (Devillard et al. 2016). Additionally, for example, women still work more unpaid hours than men and suffer from gender pay gaps (Arulampalam et al. 2007). It seems that stereotypes and prejudices remain as the main barriers in terms of gender diversity in organizations. Discrimination concerning gender, namely unequal treatment of women, is specifically evident, which is not justified by any objective reasons (Wieczorek-Szymańska and Leoński 2017). What is more, women are overrepresented in so called “feminized professions”, like teachers and nurses (Kaźmierczyk and Żelichowska 2017), but face a “glass ceiling” in professions dominated by men (Furmańczyk and Kaźmierczyk 2017). That is why there is a need to join the discussion about gender diversity and its impact on the work environment.

2. Material and Methods

3. Analyzing Organizational Maturity in Gender Diversity Management

3.1. Conceptual Model of Organizational Maturity in Gender Diversity Management

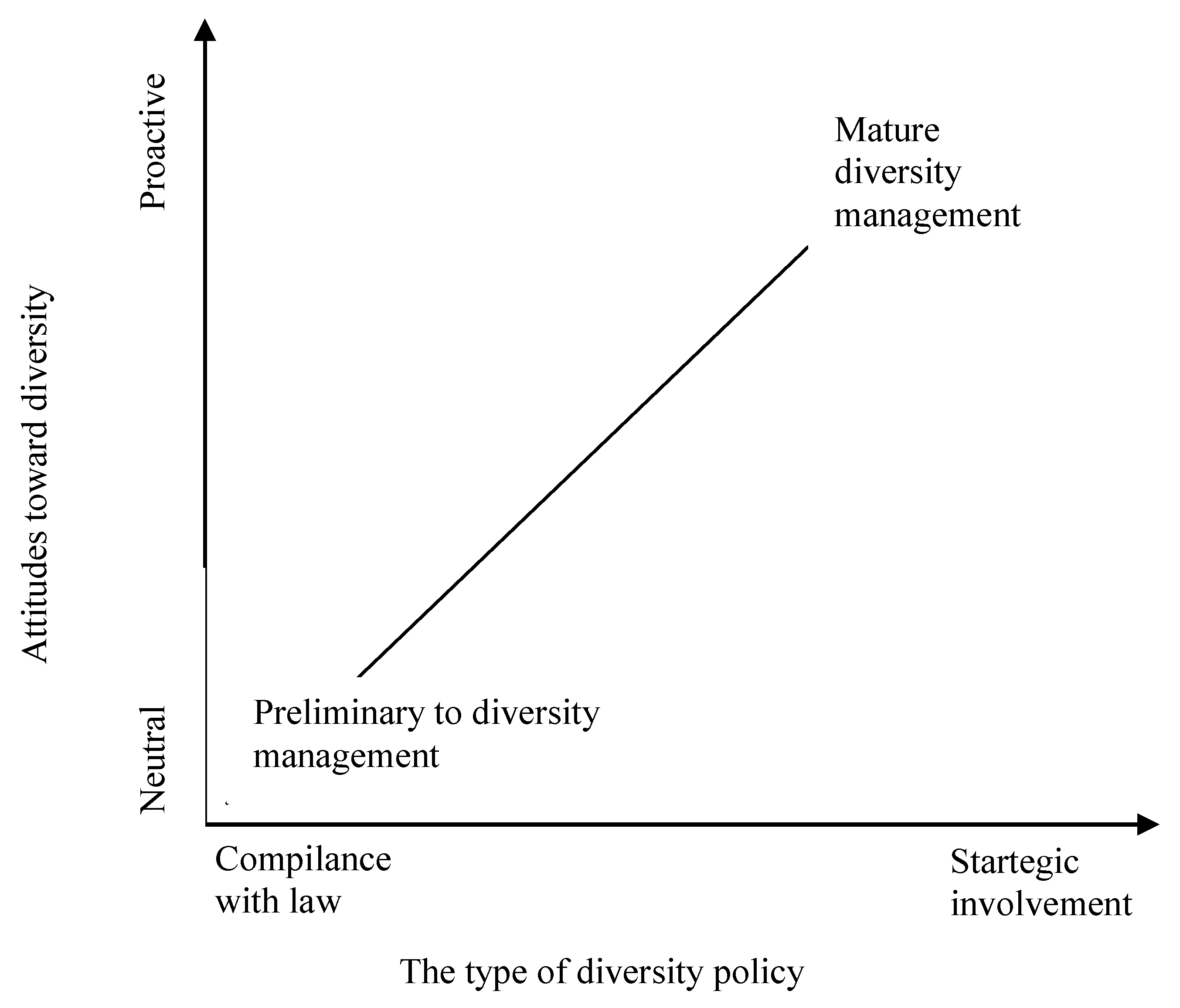

- The model is a sort of continuum on which one can place an organization according to two factors (Figure 1): organizational attitudes toward GD of employees, which vary from neutral to proactive, and the type of GD policy which varies from compliance with antidiscrimination law to strategic policy.

- Each organization that meets at least two conditions, namely neutral attitude toward diversity and the observance of antidiscrimination law, can be place on the continuum. The location on the graph depends on the type of activities undertaken within DM.

- The organization that does not fulfill the conditions mentioned in the second point cannot be taken into consideration in the model of maturity in DM, as they do not manage diversity at all.

3.2. Research Findings

3.2.1. Case Study 1: The University of Szczecin

Socio-Economic Conditions in Poland

The Characteristics of the Polish Academic Sector

Gender Diversity Management in the University of Szczecin

3.2.2. Case Study 2: The University of Cordoba

Socio-Economic Conditions in Spain

The Characteristic of Spanish Academic Sector

Gender Diversity Management in the University of Cordoba

4. Results and Discussion

- Polish universities function in a society with a bigger gender gap and lower women’s participation in the labor market than in the case of Spain. At the same time, Polish women work more unpaid hours.

- On the other hand, Polish women, more often than Spanish ones, occupy higher positions, such as legislators, senior officials and managers. Additionally, the wage gap between men and women is lower in Poland than in Spain.

- In both cases, there are more women than men in the societies, but, at the same time, they are a minority in being members of boards of publicly traded companies.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- About the University. 2018. Available online: http://en.foreigners.usz.edu.pl/o-nas (accessed on 10 July 2018).

- About UCO. 2019. Available online: http://www.uco.es/internacional/extranjeros/en/about-uco (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- Achim, Moise Ioan, Lucia Căbulea, Maria Popa, and Silvia-Ştefania Mihalache. 2009. On the role of benchmarking in the higher education quality assessment. Annales Universitatis Apulensis Series Oeconomica 11: 850–57. [Google Scholar]

- Adusei, Michael, Samuel Y. Akomea, and Kwasi Poku. 2017. Board and management gender diversity and financial performance of microfinance institutions. Cogent Business and Management 4: 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpinar-Sposito, Cansu. 2013. Career Barriers for Women Executives and the Glass Ceiling Syndrome: The Case Study Comparison between French and Turkish Women Executives. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 75: 488–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Muhammad. 2016. Impact of gender-focused human resources management and performance: The mediating effects of gender diversity. Australian Journal of Management 41: 376–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulampalam, Wiji, Alison L. Booth, and Mark L. Bryan. 2007. Is There a Glass Ceiling over Europe? Exploring the Gender Pay Gap across the Wage Distribution. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 60: 163–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besler, Senem, and Hakan Sezerel. 2012. Strategic Diversity Management Initiatives: A Descriptive Study. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 58: 624–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella, Carmen, Silvia Rueda, Emilia López-Inesta, and Paula Marzal. 2019. Gender Diversity in STEM Disciplines: A Multiple Factor Problem. Entropy 21: 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, Josephine, Deborah A. Cook, Deidre McDonald, and Sarah North. 2009. We, They, and Us: Stories of Women STEM Faculty at Historically Black Colleges and Universities. In Doing Diversity in Higher Education: Faculty Leaders Share Challenges and Strategies. Edited by Winnifred. R. Brown-Glaude. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, pp. 103–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cech, Erin A. 2013. The self-expressive edge of occupational sex segregation. American Journal of Sociology 119: 747–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Statistical Office. 2017. Higher Education Institutions and their Finances in 2016; Warszawa: Central Statistical Office. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/en/defaultaktualnosci/3306/2/10/1/higher_education_institutions_and_their_finances_in_2016.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2018).

- Charles, Maria, and Karen Bradley. 2009. Indulging our gendered selves? Sex segregation by field of study in 44 countries. American Journal of Sociology 114: 924–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, Thoo Ai, and Huam Hon Tat. 2015. Does gender diversity moderate the relationship between supply chain management practice and performance in the electronic manufacturing service industry? International Journal of Logistic-Research and Application 18: 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Sangmi, Ahraemi Kim, and Michálle E. Mor Barak. 2017. Does diversity matter? Exploring workforce diversity management, and organizational performance in social enterprises. Asian Social Work and Policy Review 11: 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Sungjoo, and Hall G. Rainey. 2010. Managing diversity in US Federal Agencies: Effects of Diversity Management on employee Perceptions of Organizational Performance. Public Administration Review 70: 109–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claeys-Kulik, Anna L., Thomas Ekman Jørgensen, and Henriette Stöber. 2019. Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in European Higher Education Institutions. Results from the INVITED Project. Brussel: European University Association Asil. 51p. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell, Christopher, and Edward J. Kellough. 1994. Women and minorities in federal government agencies: Examining new evidence from panel data. Public Administration Review 54: 265–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, Tayllor. 1991. The Multicultural Organization. Academy of Management Executive 5: 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, Faye J., and Alison Konrad. 2002. Affirmative action in employment. Diversity Factor 10: 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Devillard, Sandrine, Sandra Sancier-Sultan, Alix de Zelicourt, and Cécile Kossoff. 2016. Women Matter 2016 Reinventing the Workplace to Unlock the Potential of Gender Diversity. McKinsey & Company: pp. 1–34. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/featured%20insights/women%20matter/reinventing%20the%20workplace%20for%20greater%20gender%20diversity/women-matter-2016-reinventing-the-workplace-to-unlock-the-potential-of-gender-diversity.ashx (accessed on 9 July 2020).

- Dwyer, Sean, Orlando C. Richard, and Ken Chadwick. 2003. Gender diversity in management and firm performance: the influence of growth orientation and organizational culture. Journal of Business Research 56: 109–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2011. Strategy for Equality between Women and Men 2010–2015. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/?uri=LEGISSUM%3Aem0037 (accessed on 15 October 2019).

- European Social Charter. 1961. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/CoERMPublicCommonSearchServices/DisplayDCTMContent?documentId=090000168006b642 (accessed on 14 July 2019).

- Foldy, Erica G. 2004. Learning from diversity: A theoretical exploration. Public Administration Review 64: 529–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furmańczyk, Joanna, and Jerzy Kaźmierczyk. 2017. Zaangażowanie biznesowe pracowników naukowych (na przykładzie Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Poznaniu. Studia Oeconomica Posnaniensia 5: 100–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrick, Delwyn. 2014. Comparative Case Studies: Methodolical Briefs—Impact Evaluation No 9. Methotolical Briefs 9: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Howe-Walsh, Liza, and Sarah Turnbull. 2016. Barriers to women leaders in academia: tales from science and technologies. Studies in Higher Education 41: 415–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamka, Beata. 2011. Czynnik Ludzki we Współczesnym Przedsiębiorstwie—zasób czy Kapitał? Od Zarządzania Kompetencjami do Zarządzania Różnorodnością. Warszawa: Oficyna Wolters Kluwer Business. 384p. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, William B., and Arnold H. Packer. 1987. Workforce 2000: Work and Workers for the 21st Century. Indianapolis: Hudson Institute. 143p. [Google Scholar]

- Joplin, Janice R. W., and Catherine S. Daus. 1997. Challenges of Leading Diverse Workforce. The Academy of Management Executive 11: 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandola, Rajvinder, and Johana Fullerton. 1998. Diversity in Action: Managing the Mosaic, 2nd ed. London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD). [Google Scholar]

- Kaźmierczyk, Jerzy, and Elżbieta Żelichowska. 2017. Satisfaction of Polish bank employees with incentive systems: an empirical approach. Baltic Region 9: 58–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenawinna, K. A. S. T., and Thuduwage Lasanthika Sajeevanie. 2015. Impact of Glass Ceiling on Career Development of Women: A Study of Women Branch Managers in State Owned Commercial Banks in Sri Lanka. Paper presented at 2nd International HRM Conference, Nugegoda, Sri Lanka, October 17. [Google Scholar]

- Konrad, Alison M., Yang Yang, and Cara C. Mauer. 2016. Antecedents and Outcomes of Diversity and Equality Management Systems: an Integrated Institutional Agency and Strategic Human Resources Management Approach. Human Resources Management 55: 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawthom, Rebecca. 2003. Przeciw wszelkiej nierówności: Zarządzanie różnorodnością. In Psychologia pracy i Organizacji. Edited by Nik Chmiel. Gdańsk: GWP, pp. 417–38. [Google Scholar]

- McMahan, Gary C., Myrtle P. Bell, and Meghna Virick. 1998. Strategic Human Resources Management: Employee Involvement, Diversity, and International Issues. Human Resources Management Review 3: 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meric, Ismail, Mustafa Er, and Mustafa Gorun. 2015. Managing Diversity in Higher Education: USAFA Case. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 195: 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades. 2019. Datos y Cifras del Sistema Universitario Español. Publicación 2018–2019. Available online: https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/dam/jcr:2af709c9-9532-414e-9bad-c390d32998d4/datos-y-cifras-sue-2018-19.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Moore, Sarah. 1999. Understanding and Managing Diversity among Groups at Work: Key Issues of Organizational Training and Development. Journal of European Industrial Training 23: 208–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (European Commission). 2019. She Figures 2018. Gender in Research and Innovation. Statistics and Indicators. Luxemburg: Office of the European Commision. 216p. [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowska-Grunt, Joanna, and Judyta Kabus. 2014. Zarządzanie różnorodnością na uczelniach wyższych na przykładzie Politechniki Częstochowskiej. Zeszyty Naukowe Politechniki Częstochowskiej, Zarządzanie 14: 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Opstrup, Niels, and Anders R. Villadsen. 2015. The Right Mix? Gender Diversity in Top Management Teams and Financial Performance. Public Administration Review 75: 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, Heather R., Kimberly M. Ellis, and Peggy Golden. 2015. Performance effects of top management team gender diversity during the merger and acquisition process. Management Decision 53: 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, Laurie J., Amy Kirschke, Seaton Pamela, and Leslie Hossfeld. 2009. Challenges for Women Department Chairs. In Academic Chairpersons Conference Proceedings. 33rd Academic Chairpersons Conference, Charleston, SC. Charleston: New Prairie Press. Available online: https://newprairiepress.org/accp/2016/Trends/2 (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Pits, David, and Elisabeth Jarry. 2007. Ethnic diversity and organizational performance: Assessing diversity effects at the managerial and street levels. International Public Management Journal 10: 233–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Podsiadlowski, Astrid, Sabine Otten, and Karen I. van der Zee. 2009. Diversity Perspectives. Paper presented at Symposium on Workplace Diversity, Groningen, The Netherlands, April 15. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, Gary N., and Anthony D. Butterfield. 2015. The Glass Ceiling: What have we learned 20 years on? Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance 2: 306–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccucci, Norma. 2002. Managing Diversity in Public Sector Workforces. Oxford: Westview Press. 183p. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, Orlando C., Tim Barnett, Sean Dwyer, and Ken Chadwick. 2004. Cultural diversity in management, firm performance, and the moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation dimensions. Academy of Management Journal 47: 255–66. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, Orlando C., Susan L. Kirby, and Ken Chadwick. 2013. The impact of racial and gender diversity in management on financial performance: how participative strategy making features can unleash a diversity advantage. International Journal of Human Resources Management 24: 2571–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, Michelle. 2017. Relationships between Women’s Glass Ceiling Beliefs Career Advancement Satisfaction and Quit Intention. Walden Dissertation and Doctoral Studies 3830: 1–149. [Google Scholar]

- Sabharwal, Meghna. 2014. Is Diversity Management Sufficient? Organizational Inclusion to Future Performance. Public Personnel Management 43: 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, Paulo, José J. Brunner, Guy Haug, Salvador Malo, and Paola di Pietrogiacomo. 2009. OECD Reviews of Tertiary Education: Spain 2009. Paris: OECD. 171p. [Google Scholar]

- Seroka-Stolka, Oksana. 2016. Zespoły pracownicze w ewolucji zarządzania środowiskowego przedsiębiorstw—analiza empiryczna. Przegląd Organizacji 2: 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, Lesley. 2007. Negotiating Institutional Transformation: A Case Study of Gender-Based Change in a South African University. Cape Town: University of Cape Town. 357p. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Jie, Ashok Chanda, Brian D’Netto, and Manjit Monga. 2009. Managing diversity through human resources management: an international perspective and conceptual framework. The International Journal of Human Resources Management 20: 235–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, Lynn M., Beth G. Chung-Herrera, Michelle A. Dean, Karen Holcombe Ehrhart, Don I. Jung, Amy E. Randel, and Gangaram Singh. 2009. Diversity in Organizations: Where are we now and where are we going? Human Resources Management Review 19: 117–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, Stanley F., Robert A. Weigand, and Thomas J. Zwirlein. 2008. The business case for commitment to diversity. Business Horizons 51: 201–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talke, Katrin, Søren Salomo, and Alexander Kock. 2011. Top Management Team Diversity and Strategic Innovation Orientation: The Relationship and Consequences for Innovativeness and Performance. Journal of Product Innovation Management 28: 819–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Roosevelt R. 1990. From affirmative action to affirming diversity. Harvard Business Review 68: 107–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- UNESCO. 2017. Cracking the Code: Girls’ and Womens’ Education in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM). Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 85p. [Google Scholar]

- Urbaniak, Bogusława. 2014. Zarządzanie różnorodnością zasobów ludzkich w organizacji. ZZL (HRM) 3– 4: 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- van Knippenberg, Daan, Jeremy F. Dawson, Michael A. West, and Astrid C. Homan. 2011. Diversity faultiness, shared objectives, and top management team performance. Human Relations 64: 307–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Cupeiro, Susana, and Mary A. Elston. 2006. Gender and academic career trajectories in Spain from gendered passion to consecration in a Sistema Endogamico? Employee Relations 28: 588–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, Patrick, Marc Eulerich, and Carolin van Uum. 2014. Impact of management board diversity on corporate performance. Betriebswirtchaftliche Forschung und Praxis 66: 581–601. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, Pieter. 2010. Diversity Management in Higher Education: A South African Perspective in Comparison to a Homogeneous and Monomorphous Society Such as Germany. Gütersloh: Centre for Higher Education Development gGmbH. 157p. [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek-Szymańska, Anna. 2017. Organizational maturity in diversity management. Journal of Corporate Responsibility and Leadership 4: 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek-Szymańska, Anna, and Wojciech Leoński. 2017. Gender Diversity in Polish Enterprises. Social, Economic and Law Research 4: 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worldwide Economic Forum. 2016. The Global Gender Gap Report 2016. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-gender-gap-report-2016 (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Worldwide Economic Forum. 2017. The Global Gender Gap Report 2017. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-gender-gap-report-2017 (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Worldwide Economic Forum. 2018. The Global Gender Gap Report 2018. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2018.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2019).

| 1 | The Worldwide Economic Forum publishes a yearly Global Gender Gap Report ranking 149 countries in the world, in order of how equally women are treated compared to men, with respect to economic participation and opportunities, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment. The country classified as the first is the most equal in treating women to men. |

| 2 | The subindex is based on the survey and normalized on a 0–1 scale, where 0 means that, for similar work wages, men and women are not at all equal; 1 means that, for similar work wages, men and women are fully equal. |

| 3 | Senior roles are employees who plan, direct, coordinate and evaluate the overall activities of enterprises, governments and other organizations, or of organizational units, formulate and review their policies, laws, rules and regulations. |

| 4 | ISCED is International Standards Classification of Education. 5-8 means Short-cycle tertiary education, Bachelor or equivalent, Master or equivalent, Doctoral or equivalent. |

| 5 | The career-path in academic sector in Poland is as follows: 1. Assistant Lecturer (Asystent)—an early stage of an academic career after completing the Master Desgree or shortly after PhD 2. Tutors (Adiunkt)—PhD is mandatory, 3. Associate Professor (Profesor nadzwyczajny)—the stage after the habilitation, 4. Full Professor (Profesor zwyczajny)—the highest position full capacity for learning and research. There are some other positions like: Senior Lecturer (Starszy wykładowca) and Lecturer (Wykładowca)—these are positions for employees with or without PhD and the main responsibility of the employees is didactic. |

| 6 | In the academic year 2019/2020, the internal antidiscrimination regulation was introduced, called “Regulamin Pracy w Uniwesytecie Szczecińskim w Szczecinie”: http://usz.edu.pl/wp-content/uploads/Zarządzenie-nr-132.2019-zał.-Regulamin-pracy-w-US-1.pdf. The new regulations were introduced on 13.09.2019, and for this reason, they are not widely discussed, as the data for article were gathered before that date. |

| 7 | The index is based on the response to the following survey question: In your country, to what extent do companies provide women the same opportunities as men to rise to a position of leadership? The index is on a 0–1 scale (0 is worst, and 1 is best score). |

| 8 | Who enjoy nearly unconditional tenure form of an early stage in academic career, and various categories of salaried employed staff (or non-civil servant staff) (Santiago et al. 2009). The career path in Spain in academic sector is as follows: (1) PhD candidate/research assistant (“becario/a de investigación” or “ayudante”); (2) postdoctoral researcher (“profesor ayudante doctor”); (3) lecturer (“contratados/as doctor”); (4) professor/a B (“profesor/a titular”/associate professor); (5) professor/an A (“catedrático”/full professor). |

| 9 | Civil servant academic staff: full professors—Catedrático de Universidad (CU), associate professor—professor titular (TU), Catedraticos de Escuela Universitaria (CEU), college professor—Titulares de Escuela Universitaria (TEU) (Santiago et al. 2009). |

| Author Name/s | The Name of the Model and Main Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Podsiadlowski et al. (2009) | Reinforcing Homogeneity: avoiding or rejecting diversity in favor of homogeneous workforce. Color-blind approach: practices preventing discrimination. The approach is typical for equal employment opportunities. Fairness: ensuring equal and fair treatment by supporting minority groups or reducing social inequalities. The access perspective: underlines the ability to access diverse customers by hiring people who reflect the customer market. Integration and learning perspective: Both the organization, as a whole, and employees benefit from diversity, as it creates a learning environment where mutual acceptance of minority and majority groups alike exist. |

| Moore (1999) | Antagonistic approach: It emphasizes differences and problems resulting from diverse groups of employees, e.g., the risk of conflicts and lack of common organizational identity. Neutral acceptance of diversity: Diversity in the organization is assumed to be natural, as a result of demographic changes. No particular benefits of having diverse staff is perceived, so no specific management procedures are conducted. Naive positive attitude: Managers affirm differences between people and expect automatic benefits from hiring gender-diversified employees. In consequence, they ignore the challenges of gender diversity management. Realistic approach: emphasizes the need for active management of gender diversity in the organization, in order to achieve the intended results. Both the benefits and the possible problems resulting from hiring gender diversified employees are taken into account. |

| Konrad et al. (2016) | Classical disparity structures: Organizations are too small to be covered by employment equity legislation or are not federal contractors, so without institutional pressure, decision makers can deny the existence of labor-market discrimination. As a result, DEMS include relatively few employment equality, diversity or inclusion practices. Institutional DEMS: includes multiple activities to remove barriers to diversity hiring. Configurational DEMS: covers multiple aspects of the business case for diversity, as well as institutional requirements. |

| Jamka (2011); Urbaniak (2014) | Adaptive model: removing barriers to access, and observance of antidiscrimination law. Consolidation model: Diversity is a part of the strategy of Corporate Social Responsibility, so the organizational culture is diversity oriented. The idea of diversity is used to access diverse customers. Business model: Diversity is perceived as a source of competitive advantage for an organization. The analysis of effectiveness and the balance of costs/benefits of DM programs are conducted. |

| Professors | Assistant Professors | Tutors | Assistant Lecturers | Senior Lecturers | Lecturers | Lectors | Instructors | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grand total | 22,844 | 519 | 39,332 | 11,060 | 10,670 | 4900 | 1009 | 724 | 322 |

| Of whom are women (%) | 27.9 | 31.0 | 47.5 | 53.7 | 50.9 | 60.3 | 79.5 | 56.9 | 82.6 |

| Public higher schools | 18716 | 392 | 34,842 | 10,166 | 9992 | 4041 | 879 | 672 | 272 |

| Of whom are women (%) | 28.8 | 32.4 | 47.8 | 53.5 | 51.1 | 61.7 | 80.2 | 56.8 | 82.4 |

| Non-public higher schools | 4128 | 127 | 4490 | 894 | 678 | 859 | 130 | 52 | 50 |

| Of whom are women (%) | 23.8 | 26.8 | 45.3 | 55.8 | 47.4 | 53.9 | 74.6 | 57.7 | 84.0 |

| Assistants | Tutors | Tutors with habilitation | Associate Professors | Full Professors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The number of posts in total | 221.5 | 689 | 71 | 344 | 121 |

| Of whom are women (%) | 61.38 | 58.4 | 44.9 | 46.1 | 31.5 |

| Question | Given Answer |

|---|---|

| Gender diversity among teachers hired in our university is… | a result of demographic situation in the labor market |

| To secure gender diversity within work-teams in our university, we… | obey antidiscrimination law |

| Gender diversity is… | an effect of the diversity of the labor market |

| Civil Servant Positions | Non-Civil-Servant Positions | Other | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catedráticos/as de Univesidad CU (Full Professors A) | Titulares de Universidad TU (Associate Professors B) | Catedráticos/as de Escuela Universitaria CEU (Associate Professors) | Titulares de Escuela Universitaria TEU (College Professors) | Contratados/as CON (PhD Assistants, PhD Lecturers, Non PhD Lecturers) | Emeritos EM |

| 10,017 | 28,057 | 863 | 4284 | 52,847 | 694 |

| 21.3 | 40.3 | 31.0 | 40.2 | 44.7 | 25.8 |

| CU | TU | CEU | TEU | CON | EM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grand total | 251 | 345 | 18 | 29 | 810 | 1 |

| Of whom are women (%) | 24.70 | 41.45 | 27.78 | 41.38 | 40.99 | 0.00 |

| Question | Given Answer |

|---|---|

| Gender diversity among teachers hired in our university is… | a result of demographic situation in the labor market |

| To secure gender diversity within work-teams in our university, we… | create internal antidiscrimination regulations |

| Gender diversity is… | an effect of the diversity in the labor market |

| Poland | Spain | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender Gap Score | 42 | 29 |

| Sex ratio | 1.07 | 1.04 |

| Labor force participation | 62.5% | 69.3% |

| Wage gap | 0.56 | 0.50 |

| Estimated earned income | 35.16% lower than for men | 34.03% lower than for man |

| Positions of legislators, senior officials and managers | 41.2% | 30.6% |

| Minutes of unpaid work per day | 60.0 | 51.2 |

| Members of board of publicly traded companies | 20% | 20% |

| The most popular field of graduation | Business, administration and Law | Education |

| The least popular field of graduation | Information and Communication Technologies | Agriculture, Forestry, Fishery and Veterinary |

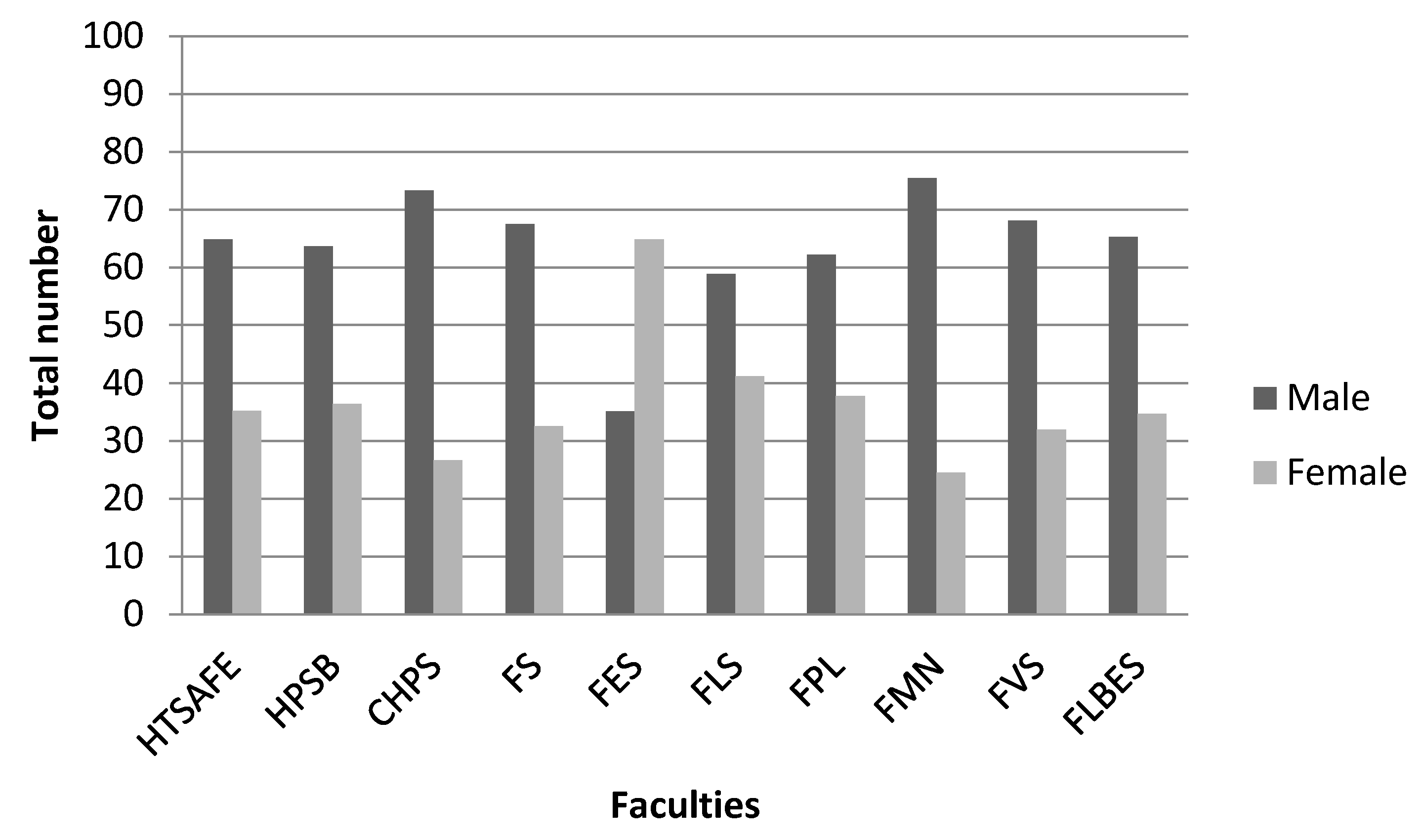

| Number of employees in academic sector | 95,400 (of which 45% are women) | 120383 (of which 40.8% are women) |

| % of women on the highest position of Full Professors | 30.0% | 21.3% |

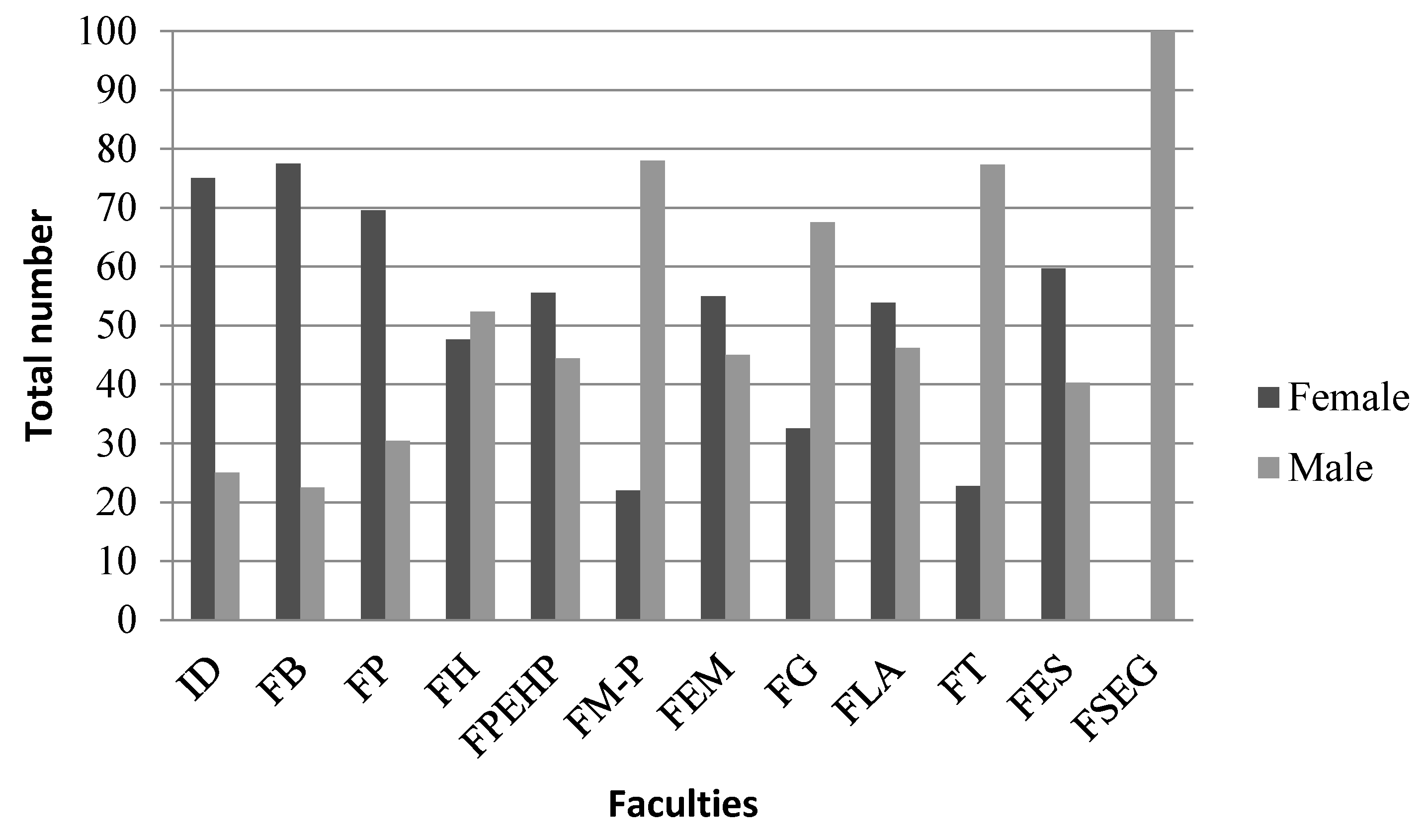

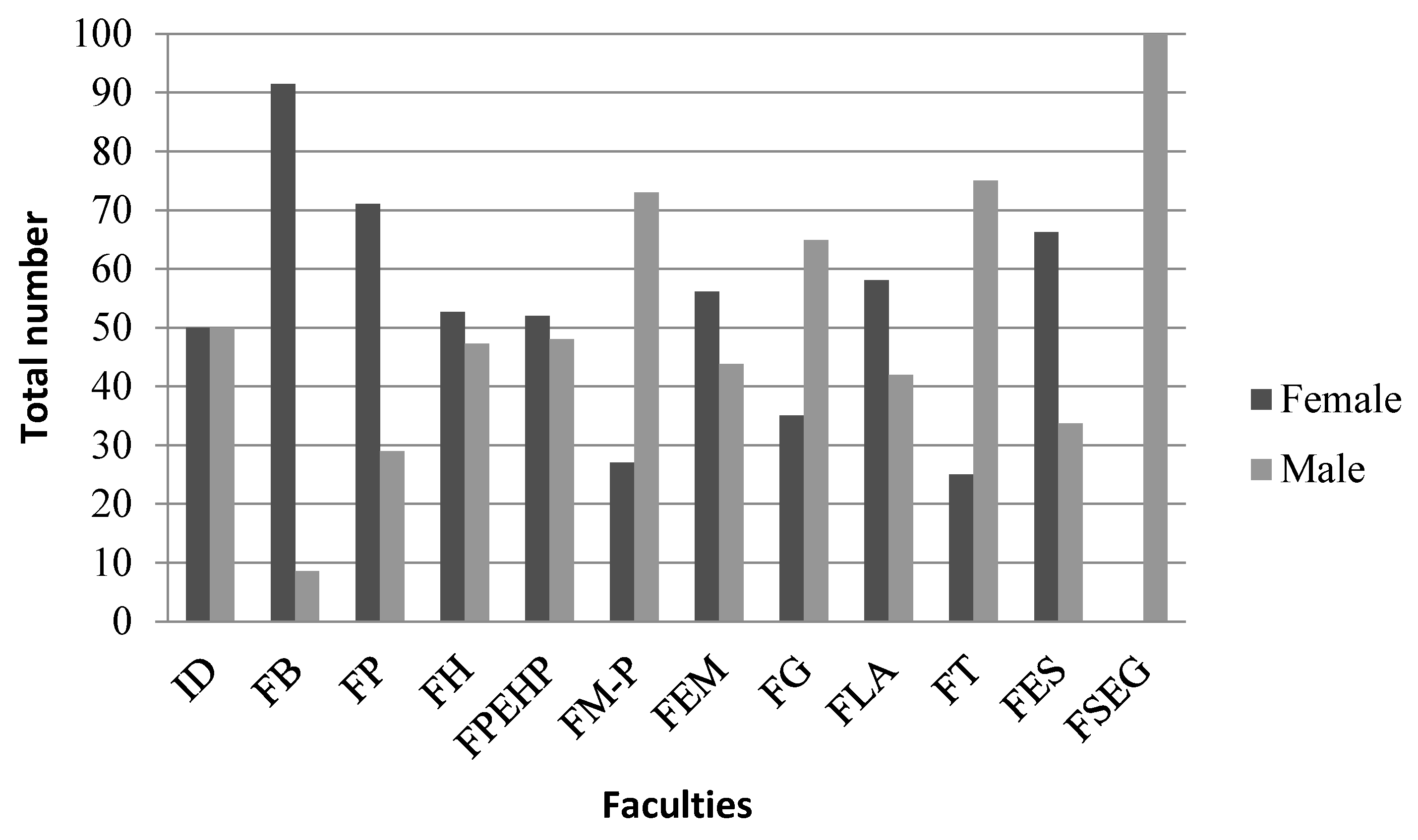

| University of Szczecin | University of Cordoba | |

| Established in | 1984 | 1972 |

| Number of faculties | 11 | 10 |

| Number of employees | 1097 (54% are women) | 1454 (38.1% are women) |

| Gender structure of employment in the faculties | 3 faculties are feminized, 4 faculties are dominated by men, 2 faculties are gender balanced | 9 faculties are dominated by men, 1 faculty is feminized |

| Gender structure of employment considering job positions | Not balanced—31.5% of full professors are women | Not balanced—24.7% of full professors are women |

| Activities that support gender diversity | No specific activities—as gender diversity is a result of diverse labor market | No specific activities—as gender diversity is a result of diverse labor market |

| The character of GDM policy | Not strategic as the policy is a result of legislation | Close to EEO approach as internal antidiscrimination procedures are introduced |

| The attitude toward GDM | Neutral—as gender diversity is a natural effect of the labor market structure | Neutral—as gender diversity is a natural effect of the labor market structure |

| The stage of maturity in DM | Preliminary stage | Preliminary stage |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wieczorek-Szymańska, A. Gender Diversity in Academic Sector—Case Study. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030041

Wieczorek-Szymańska A. Gender Diversity in Academic Sector—Case Study. Administrative Sciences. 2020; 10(3):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030041

Chicago/Turabian StyleWieczorek-Szymańska, Anna. 2020. "Gender Diversity in Academic Sector—Case Study" Administrative Sciences 10, no. 3: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030041

APA StyleWieczorek-Szymańska, A. (2020). Gender Diversity in Academic Sector—Case Study. Administrative Sciences, 10(3), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030041