1. Introduction

Organisations and their leadership face the significant challenge of becoming adaptable in complex environments, where change and uncertainty are paramount (

Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018). Today’s fast-paced environments, driven for instance by technological progress, globalisation, and vastly increased customer expectations, require them to attribute an increased level of relevance to innovation and renewal (

Jung et al. 2003). Organisational adaptability, the ability of an organisation to adapt to a changing environment and shifting market conditions (

Birkinshaw et al. 2016;

Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018), according to the seminal theory by

Teece et al. (

1997) and

Teece (

2012), can be attributed to a distinct set of dynamic capabilities. Organisations must be able to sense and assess new opportunities, to seize value from these opportunities, and ultimately reconfigure organisational structures in order to enable organisational change and maintain a competitive edge (

Teece et al. 1997;

Teece 2012). Since creating such organisational capabilities is first and foremost a leadership challenge (

Lopez-Cabrales et al. 2017;

Schoemaker et al. 2018;

Teece 2012), we must understand the specific leadership actions that propel organisational adaptability and thus long-term survival.

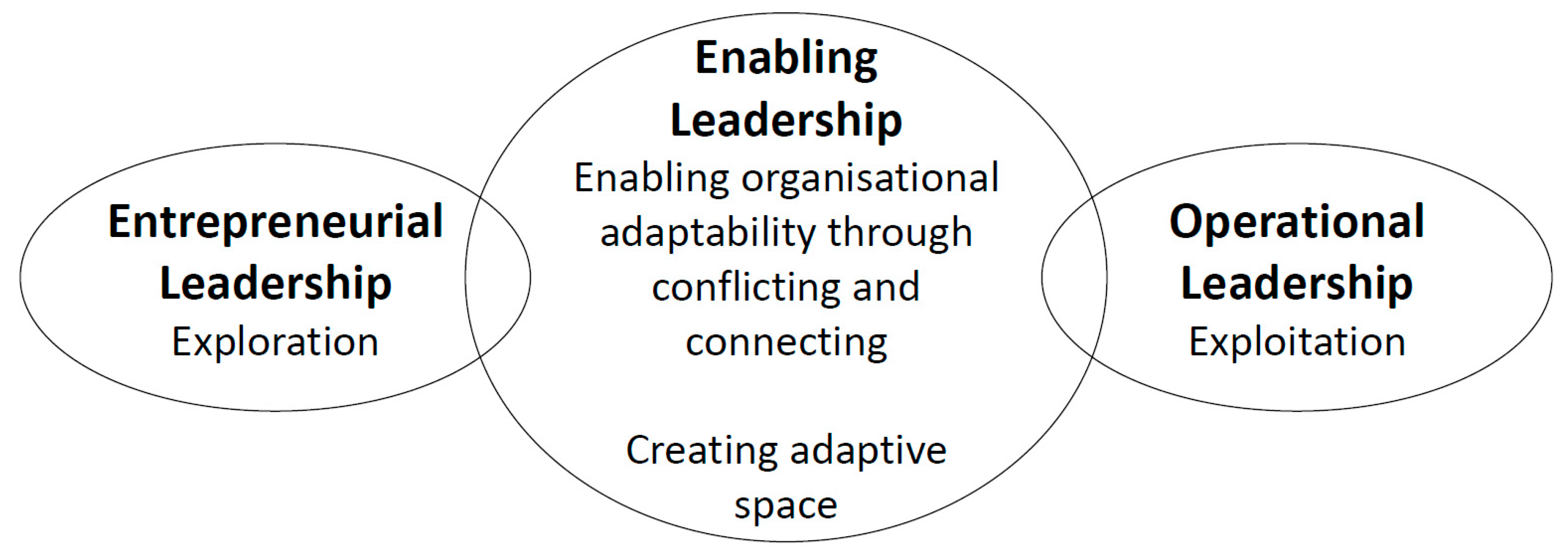

A recent conceptual model by

Uhl-Bien and Arena (

2018) integrates different research streams from a leadership perspective, and proposes a model of

leadership for organisational adaptability. At the core, this model revolves around the extensively discussed ambidexterity theme (

Rosing et al. 2011;

Simsek 2009;

Tuan Luu 2017;

Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018) which has been identified to be acting as a dynamic capability (

Birkinshaw et al. 2016;

O’Reilly and Tushman 2008). On the one hand, it entails the tensions between an organisation’s need to efficiently leverage existing capabilities and, on the other, to create new capabilities to ensure the future viability of the firm (

Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018). These target dimensions require different forms of leadership. While scholars frequently created dichotomous concepts of leadership types, such as transactional and transformational leadership as described by

Avolio et al. (

1999),

Uhl-Bien and Arena (

2018) suggest

enabling leadership as a third leadership style that combines the ambidextrous tasks of exploration and exploitation. By creating

adaptive space, that is, the conditions required to engage in the tension between exploration and exploitation, enabling leaders initiate an adaptive process within an organisation.

However, since their work remains on a conceptual level, the authors stay very vague as to the actual manifestations of the proposed types of leadership, including enabling leadership. While they provide an exhaustive conceptualisation, they do not describe how enabling leadership, and the adaptive space that is thereby created, are applied in practice. Thus, following the authors’ call to action, the purpose of this work is to “study the … ways leaders enable (or stifle) the adaptive process” (

Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018, p. 100), focusing on enabling leadership and using the example of management consulting firms. Consulting firms were chosen primarily because the consulting industry is shaped by ever changing market conditions and new requirements for their consulting portfolio. The following research question will further guide this work: How do enabling leaders create adaptive space in order to position their organisation for adaptability?

This work addresses the research question by applying a qualitative research design and conducting expert interviews. These will be analysed employing a template analysis approach in order to derive implications as to the role of enabling leadership for organisational adaptability in practice. This contributes to the literature by providing practical examples of the behaviour, processes, and structures that enabling leaders apply to create adaptive spaces, and of instances of adaptive space itself.

3. Materials and Methods

Uhl-Bien and Arena (

2018) call to action by suggesting to “study the … ways leaders enable (or stifle) the adaptive process” (

Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018, p. 100). They highlight that in other areas of organisational research, theories have been primarily built on qualitative case studies (

Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018) as a means to generate propositions. As

Baur and Blasius (

2019) state, case studies are regarded as a paradigm from the field of qualitative empirical social research. Approaches from this field aim to “observe a certain section of the social world in order to contribute to the further development of theories with these observations” (

Baur and Blasius 2019, p. 13). Guided by theories, they observe social reality and draw theoretical conclusions from the observations (

Gläser and Laudel 2009).

Case studies, in particular, analyse social processes, for example at the level of organisations, and generally limit themselves to a single case (

Baur and Blasius 2019). This clearly defined object of investigation is examined in depth in order to present it as comprehensively as possible in its complexity. With regard to existing theories, as is the case in this work, the epistemological interest of a case study lies in the further refinement or scrutiny of these theories, or in pointing out a typical example of the same (

Hering and Schmidt 2019).

As a research strategy which is directed at the examination of social processes, case studies can employ various research methods. While a direct observation of these processes would be the most suitable approach, as

Bogner et al. (

2014) explain, it is unfeasible for the ex-post examination of non-reconstructable processes or when field research is not possible. Under said conditions, expert interviews can be the means of choice to collect information which is available in the form of process knowledge of the experts to be interviewed. Additionally, from an economic perspective, expert interviews frequently are the most viable option (

Bogner et al. 2014).

According to

Gläser and Laudel (

2009), anyone with the required knowledge for the subject of research is relevant and can be considered as an interview partner. Thus, an interviewee is deemed an expert if he is or was involved in any situation or process related to the subject of research (

Bogner et al. 2014).

Alvesson and Ashcraft (

2012), however, advise to account for a balance between the principles of representativeness and quality of interviewee responses. Hence, in order to allow for a sufficient breadth and variation among experts, and for extensive coverage of the management consulting industry as the object of research, interviewees were chosen across hierarchy levels, from different organisations, and from different countries. This complies with the defined concept of distributed leadership as the underlying notion of enabling leadership (

Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018). Furthermore, to ensure a sufficient depth and quality of responses, only participants with an industry expertise of at least one year were considered. Thus, it is assumed that interviewees have deeper knowledge of the organisation and have experienced at least one cycle of annually recurring processes.

Since the epistemological interest of this work is to point out the different ways by which leaders in management consulting firms create adaptive spaces, it was deemed appropriate to follow a non-standardised, semi-structured interview approach. The interview guide was constructed based on the theoretical fundamentals, specifically on the work of

Uhl-Bien and Arena (

2018), and was structured into three blocks: a general section, that served as an introduction and comprised questions regarding innovation within the organisations, and two sections that each addressed a core process introduced in the model of leadership for organisational adaptability, that is, conflicting and connecting. The questions were used in a variable order and in variable formulations, and were supplemented by ad hoc additions in the course of the conversations (

Gläser and Laudel 2009). In a natural conversation flow, interviewees thus were guided to move in directions which were of relevance to the research, covering all aspects necessary to reconstruct a social process (

Gläser and Laudel 2009), without restricting them in bringing up thoughts, topics, and themes they regarded as important (

Alvesson and Ashcraft 2012).

Participants received a brief textual introduction and information about the purpose of the study in advance, and further information regarding the subject of the work immediately prior to the interviews. Interviews were conducted in person where possible, otherwise by telephone, and were recorded (

Gläser and Laudel 2009). Furthermore, with regard to the conduct of the interviews, the recommendations in (

Saunders et al. 2009) were considered. Increased attention was paid, e.g., to using open questions and not to create interviewer bias through formulations or behaviour (

Saunders et al. 2009).

The evaluation process began already during data collection as an early analysis of the gathered data helped to further shape the ongoing data collection. This concurrent approach in terms of an interim data analysis allowed us to reflect on the interview technique and interview guide, “to go back and refine questions … and pursue emerging avenues of inquiry in further depth” (

Pope et al. 2000, p. 114).

A total of six interviews were conducted, transcribed non-verbatim and resulting in an extensive body of complex textual data, as is regularly the case with qualitative research (

King 2012). In order to “produce an understanding of the experiences captured in the texts” (

King 2012, p. 426), this work employed a template analysis technique as proposed by

King (

2012). He positions this type of thematic analysis in the middle ground between bottom up styles of analysis, such as grounded theory or interpretative phenomenological analysis, and top down styles of analysis, such as the framework analysis technique proposed by

Pope et al. (

2000). The approach leverages an iterative process to identify themes, as is the case in grounded theory, but does not completely avoid existing theoretical or practical knowledge. Instead, some a priori themes that were defined in advance were used tentatively, and refined, supplemented or discarded later. That is, an initial coding template was developed based on existing theory, specifically considering

Uhl-Bien and Arena (

2018), and then applied for analysis, revised, modified, and re-applied (

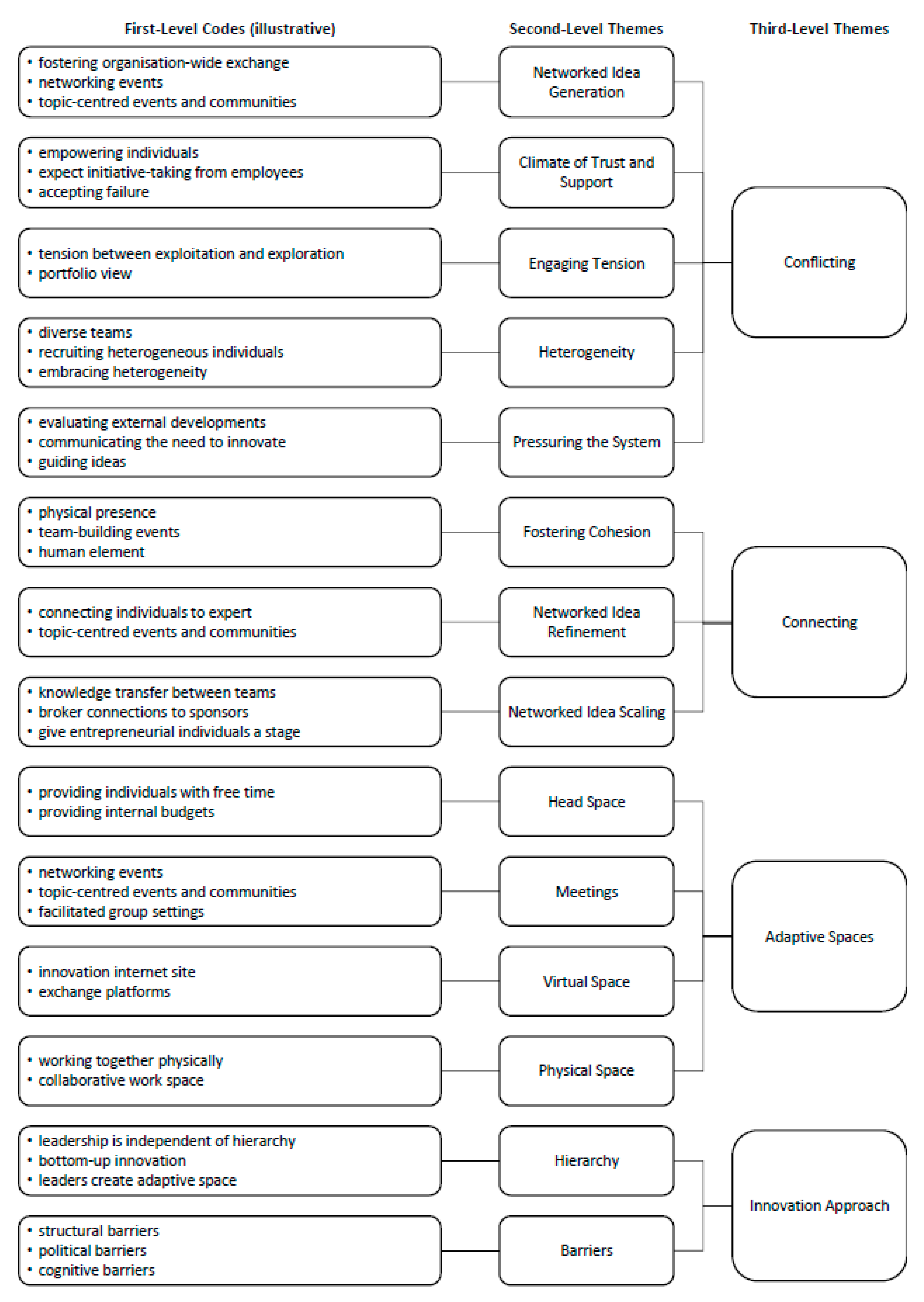

King 2012). Emerging themes were aggregated and structured hierarchically into three levels:

first-level codes on the lowest level,

second-level themes as a first layer of aggregation, and

third-level themes as a further aggregation into top-level concepts. This resulted in four third-level themes: Conflicting, Connecting, Adaptive Spaces, and Innovation Approach. The final coding template is illustrated in

Figure 2.

5. Discussion

In the following, the findings from the interviews will be discussed in relation to the research question and to relevant existing research. Connections, contradictions, differences, and similarities between the findings will be laid out. This section roughly applies the structure of the final coding template (see

Figure 2), but aggregates second-level themes where relationships were discovered.

5.1. Nurturing and Harnessing Creative Potential

The heterogeneity of individuals within organisations became apparent during the interviews. Respondents reported a high degree of diversity in terms of backgrounds, education, industry and functional expertise, locations, and personal backgrounds, which permeates the entire organisation. Heterogeneity is a core element of adaptive space (

Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018), first and foremost because it has been found to be a factor positively contributing to what is labelled an organisation’s

creative potential, and thus for idea generation and innovation. This is due to diversity in perspectives and knowledge sets within a group, and an increased idea space (

Paulus 2000;

Sarooghi et al. 2015) which can be leveraged to create novelty. It is considered essential for coping with difficult problems, as their complexity makes it imperative to unite skills from multiple domains (

Amabile and Pratt 2016).

Leaders seem to recognise and actively harness heterogeneity and creative potential. Firstly, they do so by paying attention to team composition, bringing together individuals with vastly different backgrounds to work on a given problem. Secondly, by encouraging the hiring of individuals from different fields of study, they build a diversity-promoting recruiting practice that further nurtures heterogeneity and creative potential.

Proposition 1. Enabling leaders nurture and harness the organisation’s creative potential by fostering team heterogeneity and diversity, thus creating adaptive space.

5.2. Constructing Pressure to Trigger the Adaptive Process

The adaptive process in organisations is triggered by pressures on the organisational system, that otherwise would be resistant to change and stay in equilibrium. These pressures, elsewhere described as activation triggers (

Zahra and George 2002) or disturbing elements (

Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018), can be both external, such as technology shifts or market developments, and internal, such as new product ideas generated by entrepreneurial leaders, who sense opportunities in changing environmental conditions (

Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018). However, the role of enabling leaders in this regard remains largely untouched in the model of leadership for organisational adaptability. The interview findings give an indication here.

Enabling leaders seem to be able to translate opportunities or external developments into a constructed form of pressure, thus stimulating change within the organisation. By constantly observing and evaluating external developments, highlighting their relevance and subsequently communicating the need to innovate, and framing employees’ activities with guiding ideas, leaders encourage or even persuade employees to address an adaptive challenge. They thus foster endogenous entrepreneurship (

Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018) and trigger the adaptive process. In other words, enabling leaders sense relevant market developments, without being required to provide an immediate response to the newly imposed challenges. They pass the developments on into the organisation, relieving their co-workers of the need to possess sensing capabilities, and encouraging them to seize the opportunity (

Teece 2012). This could be deemed to be both external and internal forms of pressure, as it is internally created but to employees suggests the existence of external pressure. However, although the respective behaviours were found during the interviews, they were demonstrated by very few individuals only, and no common practice emerged. This weak evidence indicates that leaders do not exhaust their full potential, or are not even aware of their role in initiating the adaptive process. This is particularly noteworthy considering that some participants, and scholars as set out above, regard adapting to changing market demands as their organisation’s core business, which requires scanning of the environment for potential shifts.

Proposition 2. Leveraging their sensing capabilities, enabling leaders identify relevant external developments and translate them into internal pressure to activate employees’ seizing capabilities, which can subsequently trigger an adaptive process in the organisation.

5.3. Ambidexterity on Different Organisational Levels

Strong evidence for the existence of tensions on different organisational levels could be identified across multiple second-level themes. Respondents described tensions between exploitation and exploration on team level or business unit level, as well as individual level. The fact that they view their work as portfolios of both types of activities emphasises this. This tension is what sits at the core of organisational ambidexterity (

O’Reilly and Tushman 2013). On an individual level, it has been labelled contextual ambidexterity, which is considered more sustainable than structural separation of both types of work. This is because contextual ambidexterity “manifests itself in the specific actions of individuals” (

Gibson and Birkinshaw 2004, p. 211), thus deeply rooting the concept in the organisation.

In order to engage this tension and to enable individuals to be ambidextrous, leaders must provide space for employees to “use their own judgment as to how they divide their time” (

Gibson and Birkinshaw 2004, p. 211). In this respect, individuals are heavily dependent on their superiors to provide them with free time or internal budgets, as set out previously. It was further described, however, that leaders indeed successfully put this into practice, with consultants being enabled to split their time between both types of work. Similar observations could be made on other levels. On a team level, leaders were described to consciously assign personnel to either exploratory or exploitative tasks, therefore compromising between generating additional revenue and innovating. An instance of organisational separation, as a solution to structural ambidexterity (

Lavie et al. 2010), could also be observed. One respondent described a dedicated innovation unit that was decoupled from the core business.

These findings strongly suggest that formal leaders and individual employees do engage the tension between the pressure to innovate and the pressure to produce, which is deemed a core element of the conflicting process (

Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018). They create ambidextrous structures on various organisational levels to embrace this tension, and aim to strike a balance between exploration and exploitation.

Proposition 3. Creating adaptive space by providing necessary recourses in terms of free time and budgets is a substantial requirement for enabling leaders and their organisations pursuing a contextual approach to ambidexterity.

5.4. Leveraging Network Structures throughout the Innovation Process

It has been observed in leadership behaviour that network structures open up adaptive spaces and facilitate the innovation process. The behaviour described with regard to networked idea generation, fostering cohesion, networked idea scaling, and networked idea refinement works towards fostering interaction or strengthening relationships between employees within the organisation. When applying a process view to innovation, and relating the behaviour to the individual process steps, it becomes apparent that it partially resembles the networked innovation process as suggested by

Perry-Smith and Mannucci (

2017) and described by

Uhl-Bien and Arena (

2018). They divide the innovation process into the four stages of idea generation, elaboration, championing, and implementation, and highlight network structures that are beneficial for each stage.

At an early stage, leaders can foster idea generation by creating connections between individuals throughout the organisation, thus providing them with access to diverse knowledge (

Perry-Smith and Mannucci 2017). Corresponding behaviour was observed with regard to the conflicting process: interviewees described that leaders would strengthen organisation-wide engagement, encourage employees to maintain broad networks, and create a multitude of different formats to connect with others. Acknowledging the notion that the generation of ideas is a social process which primarily requires interaction through weak ties (

Perry-Smith and Mannucci 2017), broad networks among employees facilitate this process. This is because the strength of ties in a broad network tends to be rather weak due to the cost of maintaining strong ties in terms of time, attention, and reciprocity (

Perry-Smith and Mannucci 2017). These types of networks can also be considered a form of creative potential, which was introduced above.

Proposition 4. To facilitate the idea generation phase of the early innovation process, enabling leaders engage the conflicting process by creating weak ties amongst individuals through organisation-wide engagement formats and encouraging broad networks.

Subsequently, when it comes to idea refinement or elaboration, group cohesion is deemed beneficial (

Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018) for the development of innovation. Entrepreneurial individuals require a few trusted and supportive contacts who encourage them to share and further pursue their innovative ideas, instead of keeping them to themselves or abandoning them (

Perry-Smith and Mannucci 2017). In the interviews, two common practices were identified that contribute to team cohesion. Leaders were described to hold regular team-building events and promote physical presence of individuals, which are both supposed to build trust and personal relationships between employees. However, even if these means are deemed conducive to the emergence of strong relationships, it remains questionable to what extent leaders, or any other third party, can actively shape such social structures. Arguably, following the notion that these strong tie contacts can also be from a private environment (

Perry-Smith and Mannucci 2017), with regard to the innovation process, it may not necessarily be an obligation for leaders to foster strong relationships within the work environment.

Proposition 5. In the process of idea refinement and elaboration, the conflicting process benefits from group cohesion, which results from interaction of individuals with strong ties. Strong ties can be fostered by enabling leaders through team-building events and encouraging teams to physically work together.

An additional cluster of leadership behaviour has been identified, that leverages networked interactions, is relevant to the elaboration stage, and supplements the findings of

Perry-Smith and Mannucci (

2017) and

Uhl-Bien and Arena (

2018). It was found in

Section 4.2.3 that leaders regularly enable what can be labelled networked idea refinement by connecting entrepreneurial individuals with experts and creating topic-centred events and communities. While, arguably, this appears to be similar to what

Uhl-Bien and Arena (

2018), with regard to the conflicting process, described as “linking up ‘poised’ agents (i.e., agents with innovative approaches or seeking change)” (

Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018, p. 99), two differences can be recognised. First, networked idea refinement is about the elaboration of existing, novel ideas, whereas the linking activities in the conflicting process are supposed to work towards idea generation. Second, in order to enable networked idea refinement, enabling leaders connect entrepreneurial individuals with experts or specialists from the respective field. The linking activities in the conflicting process, on the other hand, are described to seek to connect multiple entrepreneurial individuals with each other.

In order to promote an innovative idea, entrepreneurial individuals are required to possess influence and legitimacy in order to persuade sponsors and obtain the mandate to scale it into the operational system. It is argued that, as innovators frequently lack these characteristics and because novel ideas come with a high degree of uncertainty, influence and legitimacy can be borrowed “to reduce the perceived uncertainty by associating with well-regarded contacts” (

Perry-Smith and Mannucci 2017, p. 58). Enabling leaders can support in this championing phase by brokering connections to sponsors and lending their influence and legitimacy (

Perry-Smith and Mannucci 2017;

Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018). However, there was little evidence found for this in the interviews. Few instances of leaders were observed that broker connections between entrepreneurial individuals and sponsors in order to promote novel ideas. This leads to the conclusion that enabling leaders contribute little to the network characteristics which would be beneficial in the championing phase. Interestingly, as demonstrated in a literature overview provided by

Perry-Smith and Mannucci (

2017), there is also a significant research gap with regard to the social drivers in this phase.

Finally, during implementation, network closure and cohesion are beneficial within a group that is set to adopt an innovation, due to normative pressure and enhanced information sharing. Furthermore, relationships between individuals of different teams or organisational units, spanning the boundaries between groups, help circulate and scale an innovation (

Perry-Smith and Mannucci 2017;

Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018). The leadership behaviour working to create cohesion, which has already been described with regard to the elaboration stage, can also be understood to work towards network closure within a group, especially through the regular team-building events that were mentioned. Furthermore, the activities which have already been associated with the idea generation stage can be conducive here, as they work towards building networks and creating closure by connecting individuals throughout the entire organisation. Lastly, evidence has been found in the interviews regarding the knowledge transfer between teams via boundary-spanning connections. As became apparent in the interviews, however, leaders assume a rather passive role here, and interaction occurs on employees’ own initiative without any encouragement. This indicates that leaders focus on idea implementation within their own teams, with little interest or awareness as to their role in scaling an innovation throughout the organisation.

Proposition 6. There is unexploited potential for enabling leaders in the idea championing and implementation phase to encourage individuals to create network structures within an organisation which could support leveraging and scaling new ideas. In view of the concept of distributed leadership, individuals may in this context be encouraged to adopt leadership responsibilities and build networks on their own initiative.

5.5. Passively Creating a Supportive Climate

Conflicting, as

Uhl-Bien and Arena (

2018) describe, requires a climate of trust and support in order to be productive.

Birkinshaw and Gibson (

2004) integrate these characteristics of a work environment into what they call social support, “which is concerned with providing people with the security and latitude they need to perform” (

Birkinshaw and Gibson 2004, p. 51). They explain that this demands leadership to put effort into developing employees, shift decision-making authority to lower-level individuals, accept failure, and to take risks. As described above in

Section 4.1.4, to a large extent, this is the behaviour demonstrated by leaders within the examined organisations. They allow individuals to work in a self-determined way and make their own decisions, consider failure as learning opportunities, and give away control, which can be considered a risk for leaders.

However, this behaviour appears to be rather passive. There was little evidence for leaders actively devoting effort to the development of their subordinates. This can be interpreted as a first step towards embracing a distributed form of leadership, where leaders pass responsibility down the hierarchy, and only in a subsequent step start developing their employees to enable them to effectively assume their new responsibilities.

Proposition 7. The conflicting process benefits from a supportive climate within the organisation, which enabling leaders create by nurturing the concept of distributed leadership while developing their employees.

5.6. Strong Focus on Head Space and Meetings

Just like head space, which has been found to contribute to ambidexterity, the findings regarding meetings, virtual space, and physical space seem to affect the networked innovation process as set out above.

Uhl-Bien and Arena (

2018) view these as instances of adaptive space, as they combine different enabling leadership actions which are assumed to be opening up such space.

In a number of different forms of meetings, such as networking events or facilitated group settings, diverse individuals are brought together consciously in order for their different sets of knowledge to clash and to spark ideas. Thus, with regard to the conflicting process, this combines the characteristics of heterogeneity with the networked idea generation theme. In view of the connecting process, meetings can also be understood to enable networked idea refinement, e.g., through connecting individuals around specific topics.

Virtual space, primarily in the form of an organisation-wide innovation website, again supports networked idea generation by connecting diverse individuals. However, as they function in a similar way to topic-centred events and communities (but in a virtual way), they can mainly be seen to be conducive to networked idea refinement.

Physical spaces were reportedly not shaped very actively by leaders. However, the few observed instances differed greatly. A collaborative workspace, as described by one participant, clearly allowed employees to meet at random, thus contributing to the emergence of weak ties and broad networks, embracing heterogeneity, and enabling networked idea generation. Physically working together, like the dedicated innovation unit described by another respondent, on the other hand, works to create network closure and cohesion within the team. This creates a safe environment where individuals would share and refine their ideas.

Proposition 8. Individual enabling leadership actions with the aim of fostering collaboration and networking can impact both the conflicting and the connecting process, and are therefore crucial throughout the entire innovation process.

5.7. Abstract Nature of the Distributed Leadership Concept

As shown previously in

Section 4.4.1, interview findings seemingly suggest the prevalence of a distributed type of leadership in practice. As mentioned by

Uhl-Bien and Arena (

2018), enabling leadership happens across all levels of hierarchy, and this study found further evidence to support this claim. When the question was raised, respondents agreed that leadership was independent of hierarchy and formal roles. However, when talking about leaders during the interviews, it became apparent that respondents in many cases were nevertheless referring to their superiors, with formal decision-making authority over personnel and budgets. Arguably, in bureaucratic forms of organisations, characterised for example by hierarchical structures and coordination by rules, this is legitimate, as some means to create adaptive space are reserved to formal leaders, who have the authority to dispose certain resources. Other actions, however, such as maintaining broad networks, evaluating external developments, and brokering connections between employees, do not require any formal legitimacy, but are equally considered examples of enabling leadership. Similar to the findings discussed in

Section 5.5 regarding a supportive climate, this indicates that the idea of distributed leadership is still too abstract, intangible, and contradictory to traditional, focused leadership, and is therefore not fully internalised in the observed organisations.

Proposition 9. The establishment of the concept of distributed leadership is currently limited by the constraints of bureaucratic forms of organisation, as the disposal of resources remains with formal leaders.

5.8. Operational Leadership Is Perceived to Stifle Innovation

The barriers identified in the interviews provide further support for the findings discussed previously. Most hurdles were identified to be related to the characteristics of operational leadership that strives to order and leverages existing structures and processes. Being an opposing force to entrepreneurial leadership, they can be understood to work largely to create the tension between exploration and exploitation, and thus ambidexterity.

Rosing et al. (

2011) state that ambidextrous leadership comprises

opening leadership behaviours, such as promoting heterogeneity and encouraging experimentation, and

closing leadership behaviours, such as keeping routines and adhering to rules. In line with the top obstacles to innovation observed by

Loewe and Dominiquini (

2006), the most prominent barriers to innovation identified in this study reportedly were the constraints imposed by the core business and a lack of free time, which worked against the availability of head space, as they hinder individuals from engaging in exploratory activities. Bureaucracy, top-down decision-making, and certain performance metrics, the fear of losing control, or an over-persistence on old structures can further be interpreted as examples of operational leadership behaviour. Thus, this study relates operational leadership to

closing leadership, imposing specific barriers to organisational adaptability. It should be noted that although this behaviour may be perceived as detrimental to innovation, it is still necessary for the effective operation of an organisation’s day-to-day business. In fact,

Rosing et al. (

2011) propose that the interplay of both leadership behaviours, opening and closing, positively affects innovation.

With regard to

Uhl-Bien and Arena’s (

2018) framework, entrepreneurial and operational leadership can be related to opening and closing leadership, respectively, and thus to the concept of ambidextrous leadership.

Proposition 10. The pursuit of exploratory activities is currently limited largely by operational leadership or closing leadership behaviours, which, at the same time, play a crucial role in operationalising novelty.

6. Conclusions

With regard to the research question of how enabling leaders create adaptive space that enables organisational adaptability, this study presented exemplary means by which adaptive space is created within organisations, in particular in management consulting firms. Leaders are reportedly proficient in creating ambidextrous structures and embracing the tension between exploration and exploitation, predominantly by providing employees with enough space to pursue innovative ideas. They also actively promote heterogeneity by composing diverse teams and recruiting individuals with greatly divergent backgrounds. Leadership further fosters cohesion and succeeds at enabling networked idea generation by providing numerous opportunities to connect with others and holding regular team-building events.

On the other hand, leaders do not seem to sufficiently translate external developments into internal pressure. Unused potential was identified with regard to leveraging network structures to scale innovation. Furthermore, leaders empower employees to make their own decisions, but were shown to be passive in developing their subordinates.

The most prominent instance of adaptive space was head space, where leadership would provide employees with free time to pursue their own agenda. What also stands out are the various events that leaders hold, such as networking formats or team meetings, in order to create connections between employees. It emerged, however, that leadership was not very active to create virtual or physical forms of adaptive space, since there was little evidence for both.

Furthermore, findings strongly suggested that the organisations had not internalised the notion of distributed leadership. While first steps reportedly were taken to implement a shared form of leadership, for example by moving responsibilities down the hierarchy, the idea seemed too abstract and too much of a departure from traditional concepts of leadership, as emerged from participant responses. The task of creating adaptive space is thus mostly left to formal leaders.

Eventually, a number of barriers were identified that work against the emergence of innovation. They were shown to be associated with operational leadership and thus stand in a natural tension relationship with innovation-promoting behaviour. However, both this operational type of leadership and entrepreneurial leadership need to be accepted as co-existing forces. Ambidexterity, and hence organisational adaptability, after all, are not about overcoming operational leadership and solely prioritising innovation, but about finding a balance between both.

This work offers an insight into the structures and processes leaders leverage to open up adaptive space and positively influence the adaptive process in organisations. However, due to the qualitative nature of this research, which bases findings on the views of respondents, it is not possible to derive implications that are universally valid (

Saunders et al. 2009). This study is limited to a sample in the consulting industry, which was considered a suitable industry due to the pressure for consulting firms to continuously adapt their portfolio to rapidly changing market conditions. Although the questionnaire was not designed to address specific aspects the consulting industry, there might be different findings in industries that operate in a less dynamic environment. Future research is encouraged to explore how, for instance, manufacturing firms holding a dominant market position that may limit the need for change and adaptability incorporate the notion of enabling leadership.

Moreover, the model of leadership for organisational adaptability is a meta-theory, or a framework, that integrates multiple theories. Hence, due to the large number of underlying theories and concepts, an in-depth consideration of each of these was not possible. Network structures, as an example, which play a significant role in both the conflicting and connecting processes, could not be analysed in detail. Thus, for the sake of depth of research, future research could address this by focusing on a single or a subset of the theories integrated into the framework. Furthermore, while the applicability of the model of leadership for organisational adaptability could be shown to some degree, it presumably requires an organisation to undergo a major transformation process to fully internalise the concept. Future work should therefore study this process in order to provide implications as to the successful implementation of the theory, and identify success factors. As distributed leadership entails an increased level of responsibility on lower hierarchical levels, scholars should seek to shed light on the acceptance of this notion by both employees and leaders.