Getting Nothing from Something: Unfulfilled Promises of Current Dominant Approaches to Entrepreneurial Decision-Making

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Critical Assessment of Dominant Approaches

3. Assessing the Creativity School’s Approach

4. Assessing the Metaphysics behind the Approaches

5. Assessing the Effectuation Logic

6. Alternative Approaches

7. Alternative Approach No. 1—Focusing on Different Relevant Windfalls

8. Alternative Approach No. 2—A Co-Evolutionary Story

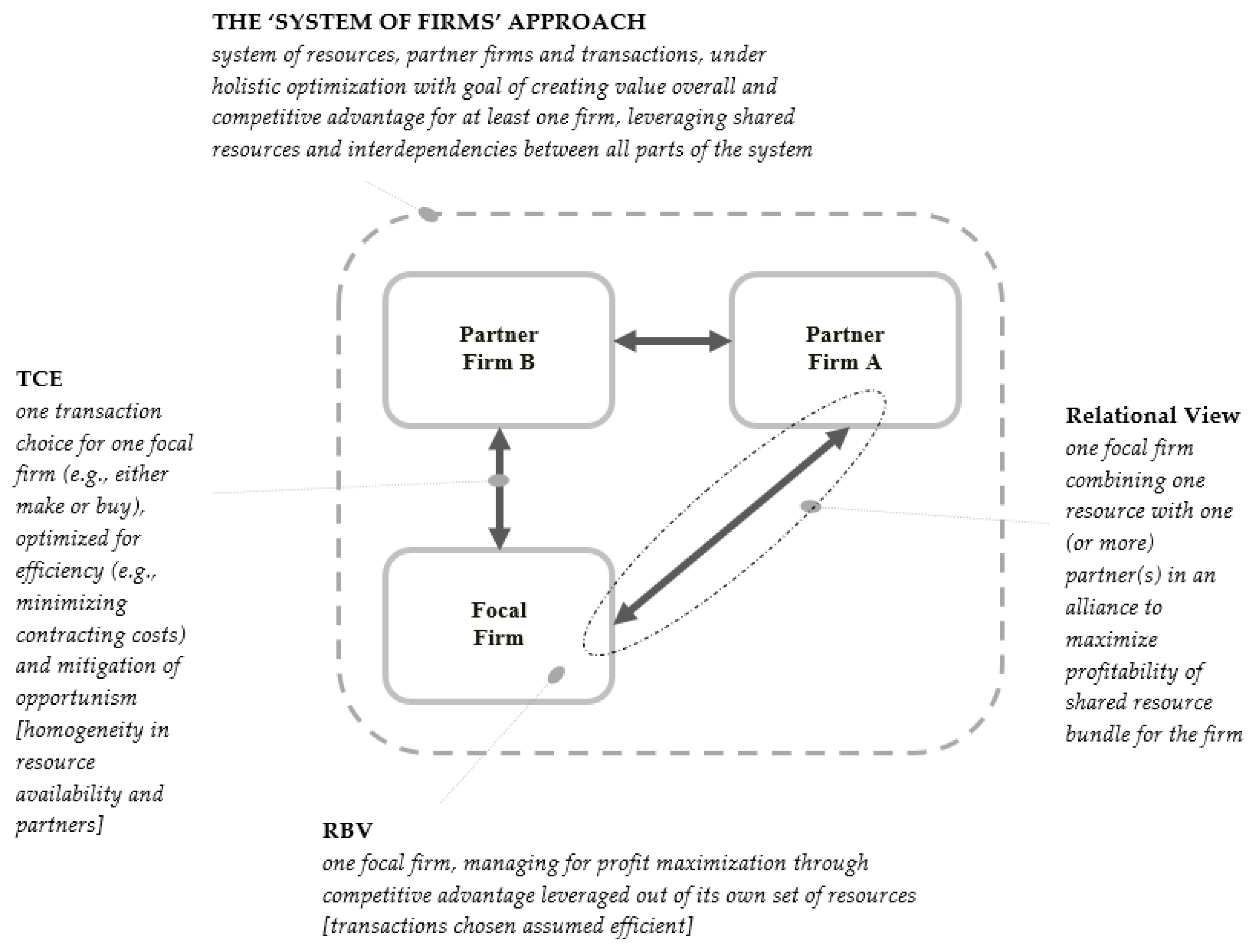

9. Alternative Approach No. 3—Breaking Theoretical Assumptions

10. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abatecola, Gianpaolo. 2014. Research in organizational evolution. What comes next? European Management Journal 32: 434–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatecola, Gianpaolo, Andrea Caputo, and Matteo Cristofaro. 2018. Reviewing Cognitive Distortions in Managerial Decision Making. Towards an Integrative Co-Evolutionary Framework. Journal of Management Development 37: 409–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatecola, Gianpaolo, Dermot Breslin, and Johan Kask. 2020. Do organizations really co-evolve? Problematizing co-evolutionary change in management and organization studies. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 155: 119964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alchian, Armen Albert. 1977. Some Economics of Property Rights. In Economic Forces at Work. Edited by Armen Albert Alchian. Indianapolis: Liberty Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, Sharon A., and Jay B. Barney. 2007. Discovery and Creation: Alternative Theories of Entrepreneurial Action. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 1: 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, Sharon A., and Jay B. Barney. 2010. Entrepreneurship and Epistemology: The Philosophical Underpinnings of the Study of Entrepreneurial Opportunities. Academy of Management Annals 4: 557–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, Sharon A., Jay B. Barney, and Philip Anderson. 2013. Forming and Exploiting Opportunities: The Implications of Discovery and Creation Processes for Entrepreneurial and Organizational Research. Organization Science 24: 301–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, Richard J. 2006. Tests of the Resource-Based View: Do the empirics have any clothes? Strategic Organization 4: 409–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, Richard J. 2015. Mobuis’ Edge: Infinite Regress in the Resource-Based and Dynamic Capabilities View. Strategic Organization 13: 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, Richard J. 2019. Conflicts of interest as corrupting the checks and balances in the post publication oversight of academic business journals. Journal of Management Inquiry 28: 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, Richard J., and M. Levesque. 2010. Testing the Resource-Based View: Simulation Results for Violating VRIO. Organization Science 21: 913–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, Richard J., Hessamoddin Sarooghi, and Andrew Burkemper. 2015. Effectuation as ineffectual? Applying the 3E theory-assessment framework to a proposed new theory of entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Review 40: 630–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, Richard J., Hessamoddin Sarooghi, and Andrew C. Burkemper. 2016. Effectuation, not being pragmatic or process theorizing, remains ineffectual: Responding to the commentaries. Academy of Management Review 41: 549–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, Beth, and Paul De Lange. 2004. Enron: An examination of agency problems. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 15: 751–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, Joe S. 1954. Economies of scale, concentration, and the condition of entry in twenty manufacturing industries. The American Economic Review 44: 15–39. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Ted, and Reed E. Nelson. 2005. Creating something from nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly 50: 329–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, Jay B. 1986. Strategic factor markets: Expectations, luck and business strategy. Management Science 32: 1231–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, Jay B. 1989. Asset stocks and sustained competitive advantage: A comment. Management Science 35: 1511–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, Jay B. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management 17: 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, Jay B., and Mark H. Hansen. 1994. Trustworthiness as a source of competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal 15: 175–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, Robert A. 2009. Effectual versus predictive logics in entrepreneurial decision making: Differences between experts and novices. Does experience in starting new ventures change the way entrepreneurs think? Perhaps, but for now, “caution” is essential. Journal of Business Venturing 24: 310–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, Léandre F. 2017. How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Barzel, Yoram. 1997. Economic Analysis of Property Rights, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, David. 1994. Objectivity. In A Companion to Epistemology. Edited by Jonathan Dancy and Ernest Sosa. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 310–13. [Google Scholar]

- Beugré, Constant D. 2017. A Neurocognitive Model of Entrepreneurial Opportunity. Intelligence, Sustainability, and Strategic Issues in Management: Current Topics in Management 18: 17–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bijker, Wiebe E. 1987. The social construction of Bakelite: Toward a theory of invention. In The Social Construction of Technological Systems. Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. 159–87. [Google Scholar]

- Brecht, Bertolt. 1978. Brecht on Theatre. Edited and Translated by John Willet. New York: Hill and Wang, Eyre Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- Breslin, Dermot. 2008. A review of the evolutionary approach to the study of entrepreneurship. International Journal of Management Reviews 10: 399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslin, Dermot, and Colin Jones. 2012. The evolution of entrepreneurial learning. International Journal of Organizational Analysis 20: 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Steve, and Paul D. Cousins. 2004. Supply and operations: Parallel paths and integrated strategies. British Journal of Management 15: 303–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, Gaylen N., Dawn R. DeTienne, A. McKelvie, and Troy V. Mumford. 2011. Causation and effectuation processes: A validation study. Journal of Business Venturing 26: 375–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, Yanto. 2017. A time-based process model of international entrepreneurial opportunity evaluation. Journal of International Business Studies 48: 423–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, Clayton M., and Joseph L. Bower. 1996. Customer power, strategic investment, and the failure of leading firms. Strategic Management Journal 17: 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, Ronald H. 1937. The nature of the firm. Econometrica 4: 386–405. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Wesley M., and Daniel A. Levinthal. 1990. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly 35: 128–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, Kathleen R. 1991. An historical comparison of resource-based theory and five schools of thought within industrial organization economics: Do we have a new theory of the firm? Journal of Management 17: 121–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofaro, Matteo. 2020. “I feel and think, therefore I am”: An Affect-Cognitive Theory of management decisions. European Management Journal 38: 344–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daston, Lorraine, ed. 2000. Biographies of Scientific Objects. Chicago: University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Davidsson, Per. 2015. Entrepreneurial opportunities and the entrepreneurship nexus: A re-conceptualization. Journal of Business Venturing 30: 674–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delios, Andrew, and Witold J. Henisz. 2000. Japanese firms’ investment strategies in emerging economies. Academy of Management Journal 43: 305–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dubin, Robert. 1969. Theory Building. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, Jeffrey H., and Harbir Singh. 1998. The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review 23: 660–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, Kirsten, and Nicolai J. Foss. 2005. Resources and transaction costs: How property rights economics furthers the resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal 26: 541–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, Ted, and Jennifer Lewis. 2002. ‘Relationships mean everything’: A typology of small-business relationship strategies in a reflexive context. British Journal of Management 13: 317–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, Denis A., and Naïma Cherchem. 2020. A structured literature review and suggestions for future effectuation research. Small Business Economics 54: 621–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, Ranjay. 1995. Does familiarity breed trust? The implications of repeated ties for contractual choice in alliances. Academy of Management Journal 38: 85–112. [Google Scholar]

- Günzel-Jensen, Franziska, and Sarah Robinson. 2017. Effectuation in the undergraduate classroom: Three barriers to entrepreneurial learning. Education+Training 59: 780–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Zisheng, Jianqi Zhang, and Linrui Gao. 2018. It is not a panacea! The conditional effect of bricolage in SME opportunity exploitation. Rand D Management 48: 603–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacking, Ian. 1999. The Social Construction of What? Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hagedoorn, John, Nadine Roijakkers, and Hans Van Kranenburg. 2006. Inter-firm RandD networks: The importance of strategic network capabilities for high-tech partnership formation. British Journal of Management 17: 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, Albert O. 1958. The Strategy of Economic Development. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobides, Michael G., Thorbjørn Knudsen, and Mie Augier. 2006. Benefiting from innovation: Value creation, value appropriation and the role of industry architectures. Research Policy 35: 1200–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirzner, Israel. 1973. Competition and Entrepreneurship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kirzner, Israel M. 1979. Perception, Opportunity, and Profit: Studies in the Theory of Entrepreneurship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 142–43. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, Frank Hyneman. 1921. Risk, Uncertainty and Profit. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, vol. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Strauss, Claude. 1966. The Savage Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liedtka, Jeanne, and Tim Ogilvie. 2011. Designing for Growth: A Design Thinking Tool Kit for Managers. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mansoori, Yashar, and Martin Lackeus. 2019. Comparing effectuation to discovery-driven planning, prescriptive entrepreneurship, business planning, lean startup, and design thinking. Small Business Economics 54: 791–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, Russ, and Robert Wuebker. 2020. Social Objectivity and Entrepreneurial Opportunities: Implications for Entrepreneurship and Management. Academy of Management Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrpouya, Afshin, and Hugh Willmott. 2018. Making a Niche: The Marketization of Management Research and the Rise of ‘Knowledge Branding’. Journal of Management Studies 55: 728–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montuschi, Eleonora. 2007. 11 Real, invented or applied? Some reflections on scientific objectivity and social ontology. Contributions to Social Ontology 15: 177–91. [Google Scholar]

- Newbert, Scott L. 2007. Empirical research on the resource-based view of the firm: An assessment and suggestions for future research. Strategic Management Journal 28: 121–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, Jack. 1997. Toward an Economizing Theory of Strategy: The Choice of Strategic Position, Assets, and Organizational Form. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, Edith T. 1959. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. New York: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, John T., Gaylen N. Chandler, and Gergana Markova. 2012. Entrepreneurial effectuation: A review and suggestions for future research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36: 837–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peteraf, Margaret A. 1993. The Cornerstones of Competitive Advantage: A Resource-Based View. Strategic Management Journal 14: 179–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, Michael E. 1980. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Priem, Richard L., and John E. Butler. 2001. Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Academy of Management Review 26: 22–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ranabahu, Nadeera, and Mary Barrett. 2019. Does practice make micro-entrepreneurs perfect? An investigation of expertise acquisition using effectuation and causation. Small Business Economics 54: 883–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, Douglas W., Dermot Breslin, and Ilfryn Price. 2019. Nurturing novelty: Toulmin’s greenhouse, journal rankings and knowledge evolution. European Management Review 16: 167–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuer, Jeffrey J., Maurizio Zollo, and Harbir Singh. 2002. Post-formation dynamics in strategic alliances. Strategic Management Journal 23: 135–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasvathy, Saras D. 2001. Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Academy of Management Review 26: 243–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeat, Jemimah J., and Alison A. Perry. 2008. Exploring the implementation and use of outcome measurement in practice: A qualitative study. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders 43: 110–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokal, Alan D. 1996. A physicist experiments with cultural studies. Lingua Franca 6: 62–64. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, David J. 1986. Profiting from technological innovation. Research Policy 15: 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, David J., Gary Pisano, and Amy Shuen. 1997. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal 18: 509–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataraman, Sankaran. 1997. The distinctive domain of entrepreneurship research. In Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence and Growth. Edited by Jerome A. Katz. Oxford: Elsevier/JAI, vol. 3, pp. 119–38. [Google Scholar]

- Welter, Chris, René Mauer, and Robert Wuebker. 2016. Bridging behavioral models and theoretical concepts: Effectuation and bricolage in the opportunity creation framework. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 10: 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, Birger. 1984. A resource based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal 5: 171–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westgren, Randall, and Robert Wuebker. 2019. An economic model of strategic entrepreneurship. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 13: 507–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, Oliver E. 1975. Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, Oliver E. 1979. Transaction-cost economics: The governance of contractual relations. Journal of Law and Economics 22: 233–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, Oliver E. 1985. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zott, Christoph, and Raphael Amit. 2010. Business Model Design: An Activity System Perspective. Long Range Planning 43: 216–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The RBV has also been proposed as a new theory of the firm (Conner 1991). Additionally, as with most recent theories, the RBV has received its share of critical analyses over time, across both fundamental empirical and logical issues. Critiques exist questioning how the RBV has been empirically tested. These suggest that the RBV has never been tested in its proposed complete form, but has only found support in loose and convenient statistically significant correlations between specific internal factors and performance outcomes (e.g., Arend 2006; Arend and Levesque 2010; Newbert 2007). Critiques also exist questioning its logic. These include concerns over the tautological nature of the value characteristic that defines focal RBV resources, a characteristic that has neither an independent definition nor a convincing origin story (Priem and Butler 2001). |

| 2 | We use the term ‘product’ here in the broadest sense as an ‘output’ of entrepreneurial action—e.g., as a consumable product, as a new process, as a new business model, as a new form of organization, as a means to identify a new factor market, and so on. |

| 3 | Alvarez and Barney have at least two other publications that effectively mirror and amplify their original piece in Alvarez and Barney (2007)—in Alvarez et al. (2013) and in the Alvarez and Barney (2010). |

| 4 | While Venkataraman (1997) does state that opportunities can be discovered or created (Venkataraman 1997, p. 122), he also states that they are discovered and created (Venkataraman 1997, p. 136) or discovered, created and exploited (Venkataraman 1997, p. 120). However, given he does not detail the difference in discovery versus creation, the implication appears to be more likely that all opportunities are discovered and then must be acted upon through creation to be exploited, a process which does not actually suggest this dichotomy. |

| 5 | We use the term ‘strategic factor’ to include any resource, capability, asset, routine, organizational form or otherwise firm-accessible or—owned ‘thing’ that has the potential to provide the organization with a competitive advantage (i.e., if exploited efficiently, it is a source of SCA [super-normal economic rents]). Such strategic factors have been described in the RBV as having a particular set of characteristics often termed VRIO or VRIN—standing for Valuable, Rare, Inimitable, Organizationally appropriable, and Non-substitutable (Barney 1986). |

| 6 | It is realistic to acknowledge heterogeneity in entrepreneurship and strategic management: all firms and contexts do differ from each other (in space and time), and often in non-trivial ways. That said, it is common to assume homogeneity over most firm factors when theorizing in order to simplify the competitive context, as that allows more focus on the main drivers of performance (e.g., Bain 1954; Porter 1980; Venkataraman 1997). Homogenization is also done in practice so that heterogeneous factors can made to serve standardized functions in order to be of use in the firm’s business model (e.g., unique people are trained to operate a welder on a mass assembly line). That homogenization provides several benefits, including improved skill applicability, larger scalability, greater share-ability, easier training, and more effective internal communication and coordination. Those benefits, in turn, generate higher production consistency, quality, and predictability. While heterogeneity is often homogenized so that the firm can do its business efficiently, heterogeneity is also often leveraged to protect how it does that business so that it is not imitated through external homogenization. That said, it is important to note that most heterogeneous firm factors are not potential sources of advantage (e.g., the heterogeneity of factors is usually not useful, or it is difficult to commercialize, or it is easy to imitate or to substitute for). Identifying what is and what is not a potentially advantageous heterogeneity is not a trivial exercise, and one that many firms do not attempt proactively for many reasons (including the difficulties in predicting uncertain possible futures—Hirschman 1958). We note that the creativity school does not identify either where advantageous heterogeneity originates or even how to identify any endowment of it. Instead, it implicitly assumes that the heterogeneity is there and that a plucky entrepreneur can take steps to identify and exploit its inherent potential value. |

| 7 | Editorial discretion appears as one of the reasons for the persistence of these dominant models. When authors of these schools also act as editors for their co-author’s and co-faculty’s pieces that support and cite that work then several apparent conflicts of interest arise that should be, but are not, checked by our journals and our academies even when these appear to violate our ethics codes and the blindness in our reviewing processes that lies at the core of the legitimacy of the quality of research in our field. |

| 8 | It is worthwhile to note that all social science phenomena confront this metaphysical debate. Most have recognized it and moved on in the practice of wissenschaft in their fields where even the mind-dependent objects and events can be (and have been successfully) scientifically studied in the empirical and experimental traditions (Daston 2000). |

| 9 | Consider the entrepreneurial activity of Warren Buffett: he represents the epitome of a Knightian entrepreneur despite the fact that he is squarely in the discovery school, searching for mispricing and exploiting it for profit, rather than creating anything new. He represents a blatant counter-example to the core metaphysical premises of the creation school. This is because even though he supposedly deals in that realm—as the entities he deals with are mostly mind-dependent, the uncertainties ‘beyond risk’, and the market failures mainly informational asymmetries—his data and models do not focus on any score of social objectivity but yet remain highly successful. |

| 10 | Additionally, it remains unclear what social value there is to (re)defining epistemological objectivity alone. Prescribing greater attention be paid by entrepreneurs to selling the sizzle without any explicit assessment of quality of the steak is to promote the next Theranos or Madoff. Making others believe deeper and wider about an idea does not alone make it worthy of pursuit let alone of social benefit. |

| 11 | The dictionary definitions of these established words are clear, and clearly not what effectuation went on to cast them as: effectuate—to bring about, to cause to happen, to accomplish, to achieve (from latin, and having nothing to do with the five characteristics of the ‘logic’ described); causation—the action of producing, anything that produces an effect (from latin, and having nothing to do with the opposite of the ‘logic’, given causing and effectuating mean the same thing); control—to exercise restraint or direction over, to manage, to operate (from middle English, and having nothing to do with a lack of prediction or planning); contingency—dependence on chance or on the fulfillment of a condition (from 1560s English, and not being the ‘opposite of knowledge’); isotropy—uniformity in all orientations (from Greek, and not being a type of real-world decision context because individual reality is not homogeneous given practical path-dependencies and neurobiological functioning). There is no scientific justification for re-defining existing words rather than naming possible new constructs that have very different meanings relative to those words. If terms have changeable meanings, involving changes that are not corrections, then any version of science allowing that is unsound. |

| 12 | Neuroscience-based experiments prove that effectuation’s core premise is wrong. It is wrong to assert that the brain works without predicting the future regardless of uncertainties. It is wrong to assert that the brain makes decisions without goals, including immediate ones. Non-predictive control does not exist. Ignoring threats like competition does not happen. The brain is a ‘real-world simulation’ machine (e.g., Barrett 2017) that continuously predicts, in order to fulfill goals, considering available means, losses, risks, contingencies, and interactions with others. |

| 13 | Each currently dominant approach enjoyed good timing, offering something different from the rational, planned, computed, search-optimizing, probability-based world of micro-economics that dominated previously. Effectuation and the creativity school promised a shift to divergent thinking as a contrast to the previous focus on analytical convergent thinking. However, neither substantively fulfilled that promise, and that is not surprising. If creativity could be boiled down to a repeatable and trainable process, it would not be creativity any more. Nowhere does effectuation actually explain how to be more creative; it is just supposed to occur at the right time and within the right budget. That promise of solving creativity is the core of the creation school, as well as many of its predecessors, like bricolage (e.g., Baker and Nelson 2005). These approaches push the idea that ex nihilo invention is possible. However, to be absolutely clear, at any metaphysical level, only nothing arises from nothing, period (Brecht 1978). Physical inventions are created from existing physical objects (by discovering new properties and uses). New beliefs are based on existing beliefs (even admitted to in the definition of subjective objectivity above). In other words, there is no way to generate something from nothing, regardless of one’s metaphysical stance. Each dominant approach also appeared to promise something like a full theory would emerge. In neither case has it. For example, effectuation remains a logic, or a process description, or some pragmatic advice, and does not rise to what it has proposed to be—a theory. Effectuation simply fails to meet the common standards for explanatory models, as has been explained in detail elsewhere (Arend et al. 2015, 2016). Despite references to ontology and epistemology, the creativity school is also not a theory, but instead simply an inconsistent and incomplete story involving social construction. In the end, neither provides a complete theory, nor new prescriptions for entrepreneurs. New prescriptions simply do not arise from only being descriptive of how real entrepreneurs were already not acting in accordance to the dominant models prior. |

| 14 | We newly propose a connection of the RBV’s definitional VRIO characteristics to the opportunity’s definitional market failure by having the opportunity define the SF’s value (i.e., the SF is valuable because it can be used to exploit a current competitive market imperfection). Therefore, a SF’s value is no longer tautologically defined as being ‘in demand’ (Priem and Butler 2001), but instead arises from the potential of the SF to address an existing market failure (a condition that differs from simple demand). |

| 15 | We believe that the future of the RBV-related decision-making research lies along several paths: One path separates out cases of certainty versus risk versus (forms of) uncertainty in specific, relevant decisions involving any firm factor-related path to competitive advantage. Another path separates out cases involving standard operating procedures versus tacit knowledge versus luck in specific, relevant process steps. Yet another path separates out ways to address asymmetric information for specific cases of arbitrage versus of legitimization versus of market creation. By focusing on understanding the constituent pieces of the RBV in terms of their separate possibilities, it will be easier to connect the SF-identification-exploitation-defense process backwards (e.g., to opportunities and new venture creation), forwards (e.g., to dynamic failure or reconstruction of past factor-based advantages), and sideways (e.g., to relation- or knowledge-based issues (Dyer and Singh 1998)). These connections can then be explained more clearly in what are likely to be behavior-focused, specific variants of an entrepreneurial RBV process. |

| 16 | We suggest that the best way to manage the meta-challenges described is to: first, break it down into recognizable pieces—i.e., the resources, partners and transactions; second, consider these pieces in combinations, optimizing, and evaluating them as possible (and interdependent) sub-systems; and, third, do this over several possible dynamic, evolving future scenarios, where sequencing has effects. |

| 17 | Failing to attend to the maintenance of the knowledge base of our field (e.g., by never removing ineffective or detrimental ideas) seems antithetical to a field’s health, let alone its legitimacy. In fact, it is illegitimate for a younger field that has been improving its research quality to be rejecting new papers that do not live up to that higher quality while retaining old papers that also do not. The failure to put any effort into maintenance of the field’s ideas is hypocritical given how very much effort we put into initial gatekeeping of ideas. We give peer editors and reviewers incredible power despite the potential conflicts of interest involved, despite the inexplicable utter lack of transparency involved (e.g., in how reviewers are assigned), despite an imperfect double-blind basis, and most often despite no guarantee that any underlying empirical data is valid (as most of it is primary and proprietary). We tolerate the standards imposed by the gatekeepers, regardless of the full knowledge that papers that should not have been accepted are and papers that should have been accepted are not. Yet, we balk at the mere suggestion that some entity should be responsible for correcting such errors or that peers should be held accountable for allowing them. Instead, we hold to the idea that the market will make the corrections naturally, even while we study a phenomenon that is only made possible due to market failures (Venkataraman 1997). Let us be clear, our ‘market for ideas’ is beset with failure. Call it Arend’s Law—that every self-regulated market will eventually drift towards corruption; and, that drift will accelerate as the market expands (in the number of participants and the size of the stakes involved). |

| Issue Approach | Lack of Originality | Characteristics | Weaknesses | Failures | Something from Nothing | Uncertainty | Prescriptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creativity School | Venkataraman described opportunity creation and origins of one opportunity-generating market failure. RBV’s inherit vs. build schools mirror discover vs. create schools. Discovery vs. invent debate ongoing in metaphysics for decades. Creativity school in entrepreneurship described by Bijkers in 1980s. | Based on contrast to a self-servingly narrowly defined ‘discovery’ school. A ‘hook’ of social constructivism—making an opportunity from nothing but belief. Timed to a spike in entrepreneurial activity and a disappointment with formal processes. | Ambiguous opportunity construct. Inapplicable to real entrepreneurs who see socially constructed (but socially objective) items, like money, as real, rather than something that they can influence others to believe in or not. Amoral—all selling is good (e.g., Theranos). | No explanation for origins of a market failure-producing opportunity. No explanation why creativity is harder than discovery. No explanation for origins for factor heterogeneity. No citing of previous metaphysics work on epistemologies involved. No citing of Bakelite case describing the creativity school | Effort, spunk, imagination and social manipulation alone can manufacture a profitable opportunity (even while others with more than that try to do the same). | Besides specifying Knightian uncertainty as a context, nothing more about which type or why it exists, is provided. | Training in social influence rather than in search and alertness. |

| Subjective Objectivity | Montuschi defines epistemological objectivity 13 years prior. Not cited, nor the relevant work of other metaphysics scholars. | Highly supportive of the creativity school. Tries to meet the need for social constructivists to find a measure of objectivity. | Prediction about un-hindering theorizing already proven wrong, given concepts needed to do so had existed for 13 years. | Knightian, without further specification (like that others facing it can be exploited). | Training in social influence/selling. | ||

| Effectuation | Experimentation, risk-sharing, bricolage, flexibility, arbitrage, and control already exist as concepts prior to their collection under this label. | Based on contrast to oddly-defined ‘causation’ logic. A ‘hook’ of sufficient constructivism—making value from any existing means. Timed to a spike in entrepreneurial activity and a disappointment with business planning. | Implicitly requires expertise (e.g., in who to partner with) to not be potentially detrimental. Five-part logic never holds holistically under testing. | Not a full theory (as argued previously). The core premise of means over goals, and a defining directive to not predict, are each contradicted by neuroscience Fails to explain how to be creative. Fails to prove that anyone can be an entrepreneur | Implies that any individual can be a successful entrepreneur, given the means they have, in a competitive marketplace, by following five rules that summarize what 27 experts did in a lab. | Implied Knightian, given the unpredictability assumption, but yet is a type one can locally control, can diversify through partnering, and can react to better than others. | Training in leveraging available means and control; in risk-sharing; in conservative investment; in pivoting, rather than in planning. |

| Opportunity Identification | Origin of SF (in Product Market) | Execution Competence | Expected Profitability | Implication for Observation/Policy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-SF is endowed, guaranteeing an opportunity, and the value for the SF in the product market. | An opportunity is identified by actions (including search and social interaction) that leverage the pre-SF. That identifies the value of the SF. | SF emerges from the pre-SF endowment (it is indirectly endowed). It has value in the opportunity identified. | Assumed competent at execution of monetizing SF. | Guaranteed longer-term profitability (SCA). | Pre-SF and new opportunity related to SCA; invest in such firms. |

| Assumed not competent at monetizing SF. | Profitability not guaranteed; inefficiencies reduce any realized advantage. | Weak, if any, link between pre-SF and CA; have policy to increase execution abilities. | |||

| Pre-SF is not endowed, allowing any or no firm to identify an opportunity. | Opportunity is endowed, guaranteeing an SF (through arbitrage—purchasing the undervalued factor prior to revealing its higher value in the opportunity). | SF emerges from arbitraging the endowed opportunity (it is indirectly endowed). It has value in the opportunity identified. | Assumed competent at execution of monetizing SF. | Guaranteed longer-term profitability (SCA). | New opportunity with SF related to SCA; invest in such firms. |

| Assumed not competent at monetizing SF. | Profitability not guaranteed; inefficiencies reduce any realized advantage. | Weak, if any, link between opportunity (or SF) and CA; have policy to increase execution abilities. | |||

| Opportunity is not endowed. Either the firm can identify it, a rival can, or no firm does. | SF is directly endowed. It has value in the firm’s existing product market (not in any new opportunity). | Assumed competent at execution of monetizing SF. | Guaranteed profitability (CA). | SF related to CA; invest in such firms, encourage exploration activities longer-term. | |

| Assumed not competent at monetizing SF. | Profitability not guaranteed; inefficiencies reduce any realized advantage. | Weak, if any, link between SF and CA; policy to increase execution abilities. |

| TCE Assumptions | Examples of Assumption-Breaking Effects of RBV |

|

|

| RBV Assumptions | Examples of Assumption-Breaking Effects of TCE |

|

|

| TCE-RBV Assumption | Issue |

|

|

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arend, R.J. Getting Nothing from Something: Unfulfilled Promises of Current Dominant Approaches to Entrepreneurial Decision-Making. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030061

Arend RJ. Getting Nothing from Something: Unfulfilled Promises of Current Dominant Approaches to Entrepreneurial Decision-Making. Administrative Sciences. 2020; 10(3):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030061

Chicago/Turabian StyleArend, Richard J. 2020. "Getting Nothing from Something: Unfulfilled Promises of Current Dominant Approaches to Entrepreneurial Decision-Making" Administrative Sciences 10, no. 3: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030061

APA StyleArend, R. J. (2020). Getting Nothing from Something: Unfulfilled Promises of Current Dominant Approaches to Entrepreneurial Decision-Making. Administrative Sciences, 10(3), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030061