Abstract

So far, issues related to the effects of ageing have been studied mainly from the perspective of national policy and international analyses. The study fills the research gap in this area focusing on the impact of demographic changes on the policy of local government units (LGUs). In the first section, a literature review of the research conducted so far has been performed. The empirical part contains the results of the study that was carried out on a sample of 131 municipalities of the Małopolska Voivodeship. The results obtained were subject to statistical analysis, based upon elements of descriptive statistics, cluster analysis and hierarchical clustering (k-means algorithm, Ward’s method) and statistical inference (Chi-square tests). It was found that the most important social problems identified by municipalities include in particular: demographic processes (indicated as significant by 71% of municipalities), population migrations (76%), unemployment (88%), alcoholism (93%) and poverty (75%). On the other hand, the following problems are perceived to a lesser extent: deficits in the level of education (15%) and social capital (36%), as well as participation in public (31%) and cultural (34%) life. However, only a few municipalities, mainly ones that are larger and more urbanised, see the key importance of the intensity of the ageing process (33% of cities with powiat rights, 14% of urban municipalities and only 4% of rural municipalities). Studies also indicate that in the light of the diagnosis of current problems, the greatest challenges associated with an ageing population are related to the lack of adequate financial resources, a decrease in a municipality’s income, a deteriorating situation in the local labour market, reduced family care potential, increased health care costs and social aid. It was also noted that from the municipalities’ point of view, the consequences of an ageing population will not only have a financial dimension, but will also require a certain redefinition of the catalogue of tasks to be carried out.

1. Introduction

One of the effects of population ageing are numerous challenges in different areas of government policies. In this context, attention shall be paid in particular to the long-term sustainability of public finances, for which the main threat is constituted by the growing costs associated with the functioning of areas such as: the pension system, healthcare, social assistance and elderly care, education system, public infrastructure, etc. Although state tasks in these areas are financed mostly from budgetary funds, the principle of subsidiarity also imposes the heavy burden of their implementation on local government units (LGUs). Hence, the demographic changes taking place enforce the revaluation of the current hierarchy of objectives as well as attribution of a new dimension to ageing-related issues both at the central level and at the local scale. At this point, two questions arise which form the basis of the research problem addressed in the study: (1) In which areas of LGU functioning are the effects of an ageing population felt and what are their consequences for the implementation of public tasks? (2) What challenges for the implementation of tasks by LGU emerge due to the progressive population ageing?

Based on the research problem expressed in such a way, the main objectives of the study were defined, namely: (1) determination of the characteristics of areas in which the effects of demographic changes are felt for the implementation of LGU tasks; (2) identification of the current LGU issues resulting from the ageing population; and (3) identification of the greatest challenges for LGUs related to this process.

The literature query indicates that although issues related to the economic effects of ageing are increasingly the subject of research and analysis, this area still constitutes an important research gap, and many questions related to the issues and challenges that this process generates remain unsettled. In the search for an answer to the questions posed, in contrast to the majority of research conducted so far, the authors focused on analysis of the influence of population ageing on the realisation of public tasks on a local level rather than from the national perspective. Furthermore, the paper takes into account not only the territorial aspect or the perspective of demographic data analysis, but also presents how municipalities themselves perceive the occurring correlated phenomena and challenges.

Local self-government has a significant position in the whole public administration system, as it is not only responsible for providing and managing a substantial share of public services, but also for the economic and social development of the local communities and areas. On average, in the European Union, 70% of public sector investments in Europe come from local and regional governments (Local and Regional Governments in Europe 2016).

The administrative structure and detailed catalogue of tasks implemented in various countries by local governments are different. In each country, however, LGUs aim to provide access to a similar set of goods and services to local communities. The fact that the conditions for the functioning of local government are similar in all countries means that they face similar problems. This applies in particular to the economic and social problems associated with an ageing population. Hence, even though the issues discussed in the paper are based on the experience of the local government in Poland (municipalities of the Małopolskie voivodship), the conclusions drawn from the analyses can be generalised to the national and international level.

The research methods used in the paper include, in the review section, a critical analysis of literature and a synthesis of the emerging conclusions, as well as an analysis of results of a questionnaire conducted among municipalities of the Małopolska Voivodeship implemented under the patronage of the Regional Chamber of Audit in Cracow in the empirical section. The research used statistical analysis, including descriptive statistics, methods of statistical inference as well as agglomerative clustering.

The structure of the paper is derived from the aforementioned objectives. The first part comprises a review of literature. The second part contains considerations regarding the effects of ageing on the implementation of individual objectives of LGUs. The third part discusses the methodology of the conducted research, and the fourth part presents the results, which allowed us to answer the research questions. The study is finished with a summary, which contains the most important conclusions from the conducted analyses and indicates the potential directions for further research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Phenomenon of Population Ageing

At present, most developed countries experience ageing of the population, which is the effect of both decreasing fertility and a rise in life expectancy. There is widespread agreement in the literature on the occurrence of the phenomenon of population aging, and the scientific debate focuses on the scale and consequences of this trend. Demographic forecasts are prepared by both international institutions (World Bank, OECD, European Commission) and national statistical centres. The issue of demographic changes is also of interest to the scientific community. For example, Lutz et al. (2008) indicate that the median population age will increase from 26.6 years in 2000 to 37.3 years in 2050, and later to 45.6 years in 2100. The broad overview of the global demography of aging is provided in Bloom and Luca (2016). On the other hand, Schoeni and Ofstedal show a synthetic presentation of the main currents in research on population ageing (Schoeni and Ofstedal 2010).

The demographic changes taking place in the European Union countries in the coming years will be more strongly felt. The effects of these changes are particularly noticeable in Poland, which for many years has ranked amongst the top 30 demographically old countries in the world. Demographic forecasts for Poland prepared by both international (UN, OECD) and national institutions point to three significant effects of the ageing of society.

First, there will be a decrease in population, which will be accompanied by a change in its structure. With a view to 2050, the total population of Poland will decrease by over 4.5 million compared to 2018 (GUS 2014). People in the post-working age will constitute an increasing share, while the percentage of people in the pre-working and working ages will drop. The demographic dependency ratio calculated as the ratio of the number of people of a non-working age (0–19 and 65+) to the number of those of a working age (20–64) is used to assess the advancement of population ageing. For example, in 2018 this ratio was 60.12% in Poland, and in 2050 it will be at a level of 96.03%. Secondly, in the group of people at a post-working age, an increasing share will be people over 80 years of age. This phenomenon is referred to as double ageing and it involves a faster than usual growth rate of the share of population aged 80 and over. In 2025–2050, the percentage of people aged 80 and over in the elderly group (60 years and more) will increase from 16.1% to 25.8% in 2050. This process is a result of the third observed demographic trend, i.e., the extended duration of life. In 1950, the life expectancy for males was slightly above 56 years, while for females it was almost 62 years. Currently, males in Poland live 17.7 years longer than they did in the middle of the last century, while the lifespan of women has been extended by 20 years (GUS 2019).

The issue of an ageing population constitutes a subject of interest for many scientific disciplines. The social issue of old age began to play an important role as a separate research trend in the 1950s (Błędowski 2002, p. 77). In the 1960s, this approach was extended to other aspects of ageing, including medical and biopsychic issues (Hobman 1978). The research conducted at that time consisted mainly of combining various aspects of old age, but it was not conducive to a thorough analysis of the studied issues (Błędowski 2002, p. 78). With the beginning of the 1970s, research once more concentrated on a separate analysis of individual aspects of population ageing. This research was first and foremost of a cross-sectional character and involved the description and assessment of the demographic-social characteristics of the researched populations. An example of such a research is an international study (Shanas et al. 2017) carried out in five countries, including Poland, which included a comparison regarding the social situation of the elderly. Another example of international research is the study of people’s living situations after retirement in France, Great Britain, the Netherlands, Sweden and the USA (Casey 1983). Subsequent research of this type was undertaken, among others by Arber and Gilbert (1989) in Great Britain and Baltes et al. (1993) in Germany.

While considering political consequences of population ageing and the new pronatalism policy in selected European Union countries, Grant and Hoorens (2006) discussed three approaches of politicians to this issue: (1) promoting increased immigration of working-age people; (2) reforming the welfare state; and (3) encouraging more childbearing. In recent years the importance of the issue of population aging has also been stressed by the World Health Organisation. In the World Report on Ageing and Health (2015), WHO indicated that one of the most important aspects of ageing is health. The response to population ageing will require a transformation of health systems from disease-based curative models to the provision of older-person-centred healthcare.

2.2. Influence of Population Ageing on Economic Growth and Public Policy

In terms of the economy, research regarding population ageing must take into account the influence of this process on long-term economic growth. An example of research focusing on economic growth is the international Lepas project which combined the modern economy with the biologically complex process of individual ageing, in other words ageing understood as a gradual deterioration of the functioning of the body and mind. Using an innovative approach to the life cycle, the project investigated how ageing affects health and productivity, with particular attention to health inequalities across the EU. The endogenous economic growth configuration model was used to study the impact of ageing on education, the labour supply, long-term economic growth, and social well-being. As part of international comparisons, the influence of ageing on creating human capital and migration flows in Europe was also analysed (Strulik et al. 2012).

The main body of literature argues that the relation between the economic growth and population ageing is negative (Bloom et al. 2010; Narciso 2010; Aigner-Walder and Döring 2012). Lee et al. (2017) argued that population ageing has a negative impact on economic growth in both the short and long term. Similarly, Maestas et al. (2016) and Eggertsson et al. (2018) proved the negative correlation between ageing and GDP growth. In their very recent study, Lee and Shin (Lee and Shin 2019) showed that population ageing negatively affects economic growth only when it reaches a certain level, and its negative effects grow nonlinearly as population ageing deepens.

However, some authors, such as Prettner (2013), proved that this relation is reversed. He examined the influence of the population ageing on long-term endogenous economic growth. His results show that the increase in longevity has a positive impact on GDP per capita output growth, while the decrease in fertility has a negative effect on per capita output. Furthermore, he claims that the positive longevity effect dominates the negative fertility effect, and as a consequence, population aging fosters long-run growth in the endogenous growth framework.

Börsch-Supan, Härtl, and Ludwig (Börsch-Supan et al. 2014) pointed out that the direct quantity and indirect behavioural effects of population aging are substantial. They claim that direct effects are due to the release of restrictions on European labour markets, which increases labour supply and entails the raise of retirement saving and the development of domestic capital stock. On the other hand, indirect behavioural effects strengthen savings, but they also weaken the labour supply. Both of the effects have a remarkable influence on transitional economic growth and living standards.

Extensive studies on the economic consequences of population aging in developed countries using the example of the Czech Republic were carried out by Arltová et al. (2016). In their opinion, population ageing is primarily an economic problem, and one of the inevitable consequences of that process in developed countries will be a rapid increase in the number of immigrants in the coming decades. As a result, there will be a necessity to modernize educational programs and introduce assimilation programs.

When considering the relation between the population ageing and economic growth, one should also note the research made by Nagarajana et al. (2016) who performed a large meta-analysis of the existing literature and deeply analysed different mechanisms through which an ageing population has an impact on economic growth.

On the more detailed level, studies on the economic consequences of population ageing focus mainly on the impact of the demographic changes on social policy, in particular on financing pension benefits from public pension schemes (Börsch-Supan 2003). It should be noted, however, that demographic changes also significantly affect other areas of socio-economic life. For example, the substitution of the workforce in the context of aging was considered already in the 1980s by Ferguson (1986). In a most recent study, Berk and Weil (Berk and Weil 2015) examined the impact of the aging of the workforce on the labour market performance and economic growth in the context of the knowledge of new technologies obtained by employees. They proved the existence of a strong correlation between the age structure of the population and the rate of labour productivity growth. Lisenkova et al. (2013) claimed that in order to compensate for production losses due to aging of the population and maintain constant output per person, an increase in labour productivity of around 15% is necessary over the next 100 years (0.14% annually). Other empirical studies on the impact of aging on the labour market on the example of Canada were conducted by Bélanger et al. (2016) and on the example of Portugal by de Albuquerque (de Albuquerque 2018).

Other examples of research areas on economic effects of ongoing demographic changes are economic activity (Lawson 2016), private consumption (Aigner-Walder and Döring 2012), expenses for health care (Hyun et al. 2016), demand for housing (Coleman 2014), and the political economy of public investments (Jäger and Schmidt 2016).

The influence of ageing on public finances in the European Union countries was addressed by Zokalj (2016), who examined the fiscal consequences of demographic changes. What is more, EU institutions are seen to examine this topic more and more often in reports and studies. The analysis of the impact of an ageing population on the stability of public finances has become the basis to present propositions for future labour programmes in the EU (Economic Policy Committee 2003). The European Commission also stresses the need to take account of demographic changes taking place in government policy planning, indicating that the sustainability of public finances in the EU can be better monitored and protected if the analyses include reliable and comparable information on possible challenges, including expected tensions caused by demographic change. To determine the effects of population ageing on public expenses, prognoses have been created related to healthcare, long-term care, education, and unemployment on the basis of a common forecast model for each position of expenses, assuming solutions that are specific for a given country in relevant cases. Subsequently, the results of these projections were aggregated to provide a general forecast of public expenditure related to an ageing population in member countries (European Commission 2018).

Taking into account the impact of the ageing process on the broadly understood public sector in Poland, the most frequently analysed areas are: pro-family policy, labour supply, intergenerational distribution of consumption and income, sources of increased employment of the elderly, retirement age, population ageing in conditions of intensive international migration, and long-term care (Lewandowski and Rutkowski 2017). In addition, research in this area also deals with the organisation of the healthcare system (Bień 2008) and changes in the education system (Maj-Waśniowska 2018). In other studies, Racław and Rosochacka-Gmitrzak (2013) analysed population ageing in the context of demographic challenges and social policy. On the other hand, Leśna-Wierszołowicz (2018) addressed the issues of the economic effects of ageing in Poland, with a particular emphasis on the pension system. The issue was also dealt with by Ciesielska and Paryna (2013). In turn, Szymańczak and Ciura (2012) analysed the challenges for social and economic policy resulting from population ageing.

2.3. Impact of Population Aging on the Local Communities

The issue of the impact of aging on the local community level is relatively rarely examined in the literature. A few studies in this field include Saito et al. (2016), who analysed the relationship between the aging population in local areas and the subjective well-being of older people. O’Brien (2014) examined the challenges of local infrastructure in the context of an aging population. The study results revealed that local councils have different abilities to provide age-friendly local infrastructure, and the challenges in rural municipalities are greater than in metropolitan areas. Supromin and Choonhakhlai (2019) investigated various models of public service provision in municipalities to improve the quality of life of older people. They indicated the factors which are essential for providing these services successfully. Almeida (2018) analysed the policy of the local and central authorities in the face of the demographic crisis and compared the economic strategies of different municipalities.

Governmental institutions and non-governmental organizations also conduct research on aging in the local dimension. The British institutions are particularly active in this area. The Age UK organisation conducts periodical analyses regarding the outcomes and scope of local government units’ activity in relation to the ageing process, while indicating the potential resulting from the development of services addressed to the elderly and the development of the silver economy (Mortimer 2014). A similar study was conducted by the Local Government Association or LGA (Local Government Association 2015). The LGA focused on opportunities and challenges for local government units in the era of an ageing society. The report investigated public services related to economic activity, civic engagement, housing, outdoor spaces and buildings, transport, social participation, and health. The financial impact of an ageing population for local government units in the UK was audited by the Audit Commission (2009). The report included analyses of five policy areas (government policy, social welfare, housing, transport, and other costs), in which demographic changes exert certain financial consequences most often associated with an increase in public expenditure.

The few analyses conducted in Poland in the field of population ageing in the local dimension include the Richert-Kaźmierska study (Richert-Kaźmierska 2016), in which the author analyses the level of awareness of Polish local government units regarding the demographic changes taking place as well as their consequences. The issue of the elderly for implementing social policy when demographic changes occur was also analysed by Błędowski (2002), who pointed out the premises for implementation of local social policy as well as its goals and principles, and identified local tasks within this scope. In turn, Kuś and Szwed (2012) analysed the possibilities of meeting the needs of the elderly in connection with the tasks of local government units.

Research on ageing in terms of spatial diversity of this process in Poland was conducted by Zeug-Żebro (2014) and Stańczak et al. (2017). Taking into account the spatial aspect of ageing, demographic changes observed in the Lubelskie Voivodeship and their implications for the implementation of social and economic policy in this region were subject to in-depth analyses. One of the most comprehensive surveys covering the implementation of tasks by local government units in Poland under the conditions of demographic changes indicates several areas of LGUs’ activity in which the effects of ageing will be particularly important: health and care services (mainly related to long-term care), tasks in the field of education and transport, and construction (GUS 2018). This research comprises detailed analyses regarding politics for the elderly (so-called senioral policy) together with the identification of expenses borne as part of the realised tasks, including those of the local government unit.

3. The Effects of Ageing Population on the Implementation of Public Tasks by LGUs

3.1. The Role of LGU in Realization of Public Tasks

With the ongoing civilizational and social changes, the nature of public tasks changes. In view of the lack of normative definition of a public task, the subject literature undertakes numerous attempts to define it.

A comprehensive approach to the issue of public tasks under administrative law is presented by Stasikowski (2009), who distinguishes between public tasks, state tasks, and administrative tasks. Under this perspective, the widest category is constituted by public tasks aimed at satisfying collective needs and pursuing the public interest. State tasks are understood as a subset of public tasks exercised primarily by the state and subordinate public entities. On the other hand, administrative tasks are the narrowest category and constitute the portion of national tasks whose implementation was entrusted to administrative authorities.

Taking into account the state’s functions, public tasks should be associated with the allocative function of public finance. Hence, the literature describes public tasks as commodities and services which are financed from public funds by entities of the public finance sector. The literature also notes accentuated legal regulations for these tasks and increased content regarding the provision of particular services (Malinowska-Misiąg and Misiąg 2014, p. 14). Szewczuk and Zioło (2008, p. 23) focusing on the functions of the state, recognise that the most important task of the public sector is the performance or financing of tasks, which by virtue of binding law is the duty of the state and local government units.

Local self-government units in Poland play a major role in the implementation of public tasks. Local self-government in Poland was reactivated after the political transformation in 1990 at the lowest municipal level. Two further levels of self-government, i.e., poviat and voivodships, were established in 1999. The basic unit of local self-government is the municipality, while municipalities and voivodships are obligatory levels, and poviats are optional, i.e., they are introduced where needed. Territorial self-government carries out public tasks not reserved by the Constitution or statutes for other public authorities. As a consequence, local self-government units at all levels participate in the implementation of public tasks that are transferred to them in accordance with the principles of decentralization, deconcentration, and subsidiarity. The catalogue and the scope of cases for the assignments to municipalities, poviats, and voivodships is similar. However, it is necessary to specify that the principle of presumed competence applies to the municipality, which means that it carries out all tasks not reserved in legal provisions for other local self-government units.

In accordance with the constitutional principle of subsidiarity, public tasks should be carried out by entities closest to the citizens, who are able to recognise the needs of the local community to the greatest extent and satisfy them. In this way, the legislator is granted the basic direction and general competence to perform a number of important public tasks for the municipality. This key importance for the municipalities is confirmed in the Act on local government units. According to article 6 of this Act, all matters of local significance are located within the scope of the municipality’s activity, and not reserved by law for other entities and local government levels. The detailed catalogue of the municipality’s own tasks contained in article 7 of the Local Government Law is open, which provides the possibility of transferring new own tasks to the municipality, and constitutes the basis for the implementation of tasks that, according to local authorities, are within the spheres of public interest and utilities (Gilowska et al. 2002).

Four groups can be identified within the municipality’s tasks. Those include assignments of: technical infrastructure (e.g., roads, water supply, and communications), social infrastructure (e.g., education, health care, social protection), security and social order (civil defence, fire protection, municipal guards), as well as spatial and ecological order (e.g., planning and spatial development, environmental protection) (Dobosz 2007). Similar groups of assignments occur in poviat and voivodships. As the second level of local self-government, the poviat performs supra-municipal public tasks, and the voivodeship realizes assignments of a regional nature. The differences in implemented tasks come down to specific measures in a given area. For example, as part of educational tasks, municipalities are responsible for running kindergartens and primary schools, poviats for secondary schools, and voivodships, among other things, for establishing and running special primary schools, secondary schools with regional and supra-regional designation, as well as for establishing and running public teacher training facilities and pedagogical libraries.

3.2. The Specificity of Selected Municipal Tasks in the Context of the Needs of the Elderly

Taking into account the descriptions defined in the introduction, particular attention is given in this section to the municipal tasks whose realisation is affected by the observed transformation of the demographic structure. These ongoing social changes, in particular those resulting from population ageing, force municipalities to confront new challenges related to the implementation of public tasks. The growing percentage of the elderly results in the necessity of a wider consideration of the needs of this social group.

In the subject literature, the starting point for considering these needs is the classical Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which constitutes an accurate reflection of the needs of older people. A closer look at the characteristics of older people, however, leads to the conclusion that in the phase of old age, the importance and intensity of selected needs changes. Moreover, as argued by Staręga-Piasek (1975), the psychosocial needs of older people are conditioned by gender, level of education, profession, personality type, health status, and family structure. Hence, in gerontology and senile psychology, there are various needs that dominate in old age (Table 1).

Table 1.

Dominant needs in old age.

From the point of view of the issues raised in the article, the proposition of Brubaker (1987) seems to be of particular importance; he analyses the needs of older people, indicating those which are the most important from the point of view of the organisation of their satisfaction system. He lists three categories of key needs for the elderly, specifically financial needs, physical needs, and socio-emotional needs. The first group is related to the dependence of older people on one source of income. The second group includes the needs related to decreased efficiency and progressive weakness of the body, and the third one constitutes the totality of needs resulting from the desire to maintain contacts and social interactions. Importantly, the indicated needs result in the necessity of not only changing the scope and nature of tasks performed by local government units, but also extending their current catalogue.

In the context of the analysed issues of the challenges of local and regional government units in the era of population ageing, tasks that are part of broadly understood social policy towards the elderly are of particular importance. On theoretical grounds, the priority objectives of this policy are to carry out activities aimed at enabling elderly people to live independently, counteracting the processes of social marginalisation of seniors, and enabling the elderly to fulfil their needs in various forms (Szarota 2010).

At the operational level, an example of the implementation of objectives of social policy towards older people is the document adopted by the Polish Council of Ministers in October 2018 “Social Policy for Older People 2030. Safety. Participation. Solidarity” (Council of Ministers 2018). This document assumes the implementation of activities for the elderly in seven basic areas: (1) building a positive image of old age; (2) supporting participation in social life and in various forms of civic, social, cultural, artistic, sports, and religious activity (3) creating conditions enabling the use of the potential of older people in economic life and in the labour market; (4) health protection, including disease prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation; (5) increasing safety by counteracting violence and neglect of older people; (6) building solidarity and intergenerational integration; (7) education: for old age (care and medical staff), until reaching old age (the whole society), through old age (from the youngest generation), and at old age (the elderly).

The listed priority areas of social policy relate to the whole of the social sphere and cover relations between politics at national, regional, and local levels. Through its bodies, the state sets general goals of social policy and creates legal and financial frameworks for their implementation. Regional policy constitutes a concretisation of the policy objectives pursued at the central level, taking into account the social characteristics of the population living in a given area. In turn, local social policy is implemented mainly at the municipal level, although this does not exclude support in selected areas by poviats (Błędowski 2002, pp. 43–47). The objectives of the local social policy approach result to the greatest extent from the situation of the local community, its living conditions, and its identified needs (Kurzynowski 1999). However, it should not be forgotten that local policy also reflects the priorities of central policy through commissioned tasks and the scope of the municipality’s statutory tasks.

Taking into account the current considerations, it should be concluded that a growing percentage of the elderly in the population will continue to have a stronger influence on the scope and hierarchy of the tasks realised by municipalities in relation to the needs of this social group. This will be particularly visible in the case of municipal tasks in the fields of: long-term care, education, culture, social activation of seniors, counteracting social exclusion, infrastructure adapted to the needs and capabilities of older people, and housing policy.

The first area (long-term care) consists of two main categories of tasks: social security and health care. The former is implemented as part of the social welfare system. On the one hand, they aim to provide income at a level that allows them to meet basic needs, including through the payment of various types of benefits. This is particularly important in the context of the dependence of households of older people on one source of income. On the other hand, these tasks are related to the provision of various types, including: care services in the place of residence, daily services provided in support centres, 24-h services provided in nursing homes and social assistance centres, as well as services provided in 24-h care centres. The second group of tasks in the field of long-term care involves providing care to bedridden and chronically ill persons who do not require hospitalisation, but have significant deficits in self-care for continuous and professional care and rehabilitation, and also require a continuation of pharmacological treatment. These tasks seem particularly important in connection with the old age-specific complaints and deterioration of general health. Although the basic source of financing healthcare is the resources of the National Health Fund, the progressive ageing of the population also requires growing involvement of municipalities in this area.

Within the area of education there are three groups of engaged participants in social life: seniors, staff (clerks), and society. The education of seniors includes various forms of lifelong learning and activities being part of the so-called informal education. The municipalities’ tasks in this area are focused on supporting and promoting the participation of older people in the process of lifelong learning (e.g., organisation of workshops, lectures, educational undertakings, Universities of the Third Age). However, it should be noted that unlike other social groups, the main tasks of the elderly’s education are not related to raising professional competences but are generally an expression of personal cognitive needs, as well as a desire to find a place in contemporary reality and learn about the mechanisms that create it. Tasks in the field of staff education include activities aimed at improving the competences of employees of the municipality’s local government units that provide services for the elderly, as well as the promotion of care professions. Education of the society boils down to building a sense of intergenerational bonding and solidarity among the local community, raising awareness of the needs of older people and ways of satisfying them, and stressing the need for an inclusive approach to seniors. The formation of socially desirable attitudes seems to be an element that can help municipalities meet the challenges of an ageing population. Greater awareness in this respect may result in an increase in the activities of the local community in meeting the needs of seniors (e.g., through volunteering or the activities of self-help organisations).

An important task of a local social policy is the creation of possibilities of the elderly’s broad participation in the cultural life and undertaking activities for the popularisation of culture. These activities are implemented by institutions established for this purpose, within which three basic groups stand out: specialised institutions for popularising culture (e.g., theatres, cinemas, galleries, philharmonics, museums, libraries), cultural and educational facilities (e.g., houses, clubs and culture or community centres) as well as socio-cultural foundations and associations. In the case of cultural and educational institutions, a special role belongs to senior clubs, whose aim is to compensate the elderly people for the loss of their social roles and to create conditions for a successful course of their adaptation to their new life situation (Zych 2007). By enabling older people to spend their free time together, clubs also enable them to meet social and emotional needs, such as the need for affiliation to a group, acceptance, emotional bond, life satisfaction, and being useful. These clubs to some extent play the role of providing self-help groups for the elderly (Kowalik 2006).

From the point of view of the elderly, the essential task of LGUs is also social activation and the counteracting of social exclusion. The aim of this task is to answer the elderly’s needs to enhance their activities, participation in social life, and interpersonal relations. The nature of this task means that they are implemented mainly in the areas of educational tasks, social assistance, and tasks in the field of culture and sport. In particular, this concerns tasks which aim to support various forms of independence and participation of the elderly in social life, their education, and enrichment of the offer of services dedicated to this social group. In addition, these tasks also include preventing discrimination based on age as well as dependence and strengthening of the development of social initiatives.

Another task which affects the quality of life of elderly people is providing infrastructure tailored to their needs and capabilities. This group of tasks is associated with shaping the broadly understood physical environment in urbanised areas, as well as green areas for recreation and leisure. The role of the municipality is to care for the quality of public infrastructure and social participation in planning and managing this infrastructure. The adaptation of space and infrastructure to the needs of seniors enables the implementation of their social and professional activities influencing the quality of their lives. These tasks are aimed at organising public space so that it is equally accessible to all, regardless of age. All members of the local society should be able to use this public space in an independent and self-sufficient way and feel safe in it (Wysocki 2015). It should be noted, however, that creating a public space that takes into account the needs of seniors is a particularly difficult task due to the huge heterogeneity of this group.

The last group of tasks involves LGU’s housing policy. The basic task of the municipality in the area of housing policy is to adapt the housing resource to the needs of seniors. At the same time, local housing policy can be active (e.g., development of instruments supporting senioral construction) or adaptation, resulting from the diagnosis of the needs of seniors. Tasks in this area can be implemented in two ways. The first is a traditional method consisting of activities related to removing architectural barriers and adapting spaces to the needs of people with limited mobility (e.g., creating multi-family buildings with the possibility of using social services such as laundry and cleaning). The second form of realisation of these tasks is the introduction of technological innovations such as remote control of devices, motion detectors, digital information services, or health telecare. The use of such techniques and adaptation of the housing stock to the needs of seniors allows for greater independence in the self-management of the household, which reduces the number of people that need to be admitted to social welfare homes (Kłobukowska 2014).

The analysis of the presented tasks of the municipality indicated that the occurring demographic changes are reflected practically in all areas of its activity. In the aspect of senioral needs, this leads to the conclusions that in the era of population ageing, it is necessary to distribute elements of local social policy differently. The theoretical considerations made on the basis of the thesis allow us to indicate general trends and conditions in which municipalities will function in the future. In order to thoroughly diagnose the existing issues in this area and ways of solving them, as well as to determine the key challenges which the ageing population poses for municipalities in the subsequent stage of analysis, a detailed empirical study was carried out.

4. Research Methodology and Sample

The results of empirical research are based upon a survey conducted under the patronage of the Regional Chamber of Audit in Cracow. These surveys were conducted in the period of September-December 2018 among all municipalities of the Małopolska Voivodeship. Małopolska Voivodeship is one of the sixteen voivoidships in Poland. With a population of 3.4 million (nearly 9% of the Polish population), it is the 4th largest voivodeship in the country. The population density of the voivodship is 223 people per square kilometre and is the second highest in the country. In 2017 gross domestic product of Małopolska amounted for nearly PLN 142.1 billion (around EUR 32 billion), which was 7.9% of Poland’s GDP. The Małopolska voivodship consists of 19 poviats formed by 182 communes, including 14 urban communes (including 3 cities with poviat status), as well as 120 rural and 48 urban-rural ones.

Of the total of 182 Małopolska municipalities, 131 units provided complete answers, which gives a level of participation in research of over 71.9% (cf. Table 2). The questionnaire was carried out using the CAWI method. In addition, taking into account technical conditions, it was also possible to provide answers in the form of a questionnaire in paper form containing a set of questions identical to the electronic version. On behalf of individual municipalities, the answers were mainly provided by the treasurers (49.62% of the total responders), secretaries of the office (16.79%), heads of relevant departments or projects (13.74%), local government executives (6.87%), persons employed as an inspector (3.05%), as well as deputies of local government executives (1.53%) and deputy treasurers (1.53%).

Table 2.

Actual structure of municipalities in Malopolska Voivodeship and the structure of the surveyed sample.

The structure of the municipalities that participated in the study, according to the type and number of inhabitants, is presented in Table 2.

The study comprises two essential steps: (1) diagnosis of key social issues currently affecting municipalities, with particular emphasis on the issue of old age and issues affecting the elderly; and (2) identification of areas in which the ageing population will have the greatest impact on the implementation of a municipality’s tasks. As part of the research, the surveyed municipalities were analysed in three cross-sections taking into account their demographic structure, type of municipality, and subjective assessment of the degree of intensity of population ageing. This measure was aimed at identifying potential differences in the scale of the occurrence of individual social issues and the perception of key challenges related to population ageing in various municipalities.

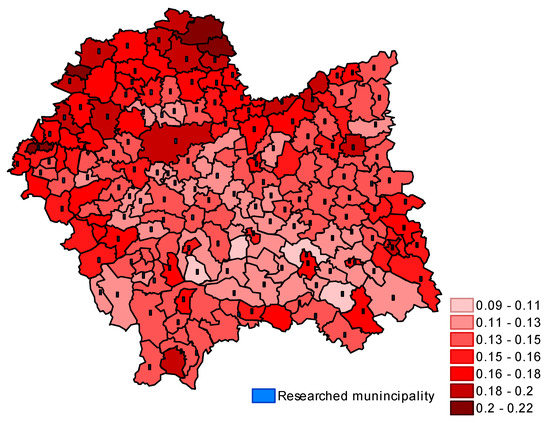

In order to verify whether the given age structure of the local community affects the given answers, all municipalities of the Małopolska Voivodship were divided into two subgroups using the k-means algorithm—‘old’ municipalities and ‘young’ municipalities. There were 74 municipalities which qualified for the first group, in which the percentage of the population over 65 exceeded 15.2% (the average percentage of people over 65 in this group was 17.2%). The second group included 108 municipalities with an average percentage of people over 65, at the level of 13.2%. After applying the division to the municipalities participating in the study, we found that there were 49 old municipalities and 82 young municipalities, which we analysed in detail (cf. Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Age structure of municipalities in Małopolska and municipalities participating in the study (percentage of people over 65). Source: Own study based on a questionnaire survey and the Local Data Bank (https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/BDLS/pages/Home.aspx).

To investigate whether the occurrence of current social issues and the areas generating the greatest risks due to the population’s ageing are influenced by the type of municipality, the analyses took into account the division of municipalities into urban, urban-rural, rural, and cities with poviat rights.

Moreover, in order to include the subjective factor in the research, the examined units were divided into five groups depending on the answer given to one of the questions in the survey. In this question, the respondent was to determine his assessment of the intensity of the ageing process in the municipality he represented on the 5-point Likert scale. The summary of answers given to this question is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Assessment of the degree of intensity of the aging process in the analysed municipalities.

Taking into account the demographic structures of municipalities and their division into old and young, it is clear that the vast majority of municipalities belonging to the first group (nearly 90% of the surveyed entities) perceive the issues of ageing and nearly 40% of them consider the intensity of this process as being high or rather high. In the case of young municipalities, such an assessment of the intensity of the ageing process was made by less than 20% of the surveyed entities. The vast majority of them assessed the occurrence of this process as being average (63%). The results of statistical verification indicate that with the significance level α = 0.05, the observed differences are not statistically significant. However, increasing the level of significance to α = 0.1 (and thus the margin of type I error) leads to the rejection of the hypothesis on an equal distribution of the ageing process assessment in the analysed types of municipalities.

In the case of dividing municipalities into types in the assessment of the degree of demographic changes, in relation to other types of municipalities, they are particularly visible in the case of cities with poviat rights, which consider the intensity of the analysed issue as being high (33% of entities in this group). In other types of municipalities, the intensity of population ageing was assessed as high by merely 16.7% of municipalities, 9.1% in urban-rural areas, and less than 5% in rural areas. However, in the case of evaluating the process intensity as average, the differences in responses are much smaller. Statistical verification of the null hypothesis with the same distribution of the assessment of the degree of ageing process intensity in the analysed municipalities showed that there are no grounds for its rejection. However, when interpreting the results of the Chi-square test, attention should be paid to the numerical value of sets of the analysed types of municipalities, which could have influenced the obtained results.

5. Results

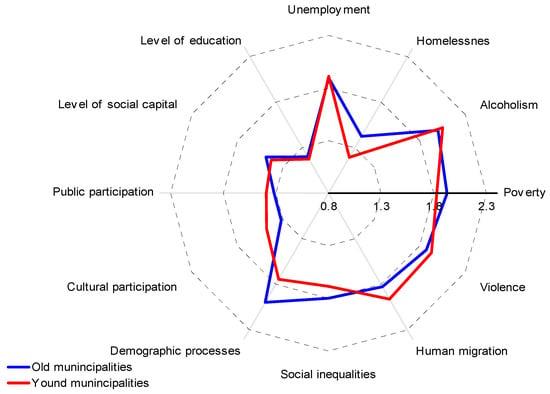

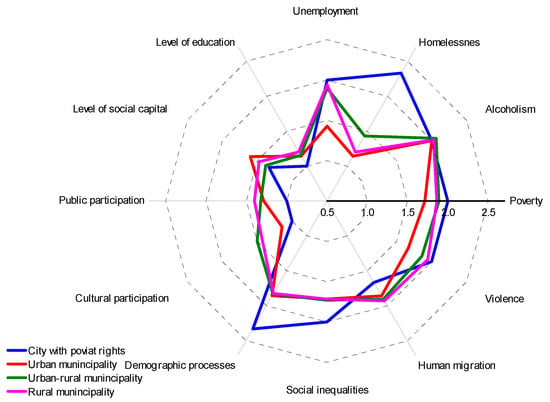

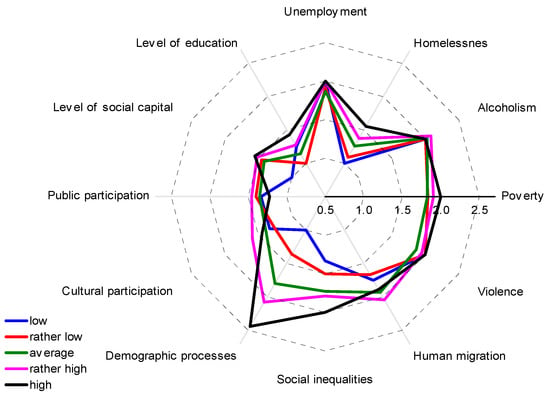

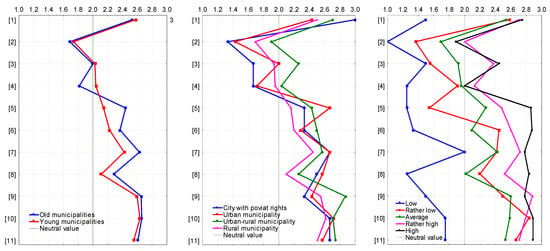

The results of analyses carried out in the area of diagnosis of social issues currently affecting municipalities are illustrated in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 in the form of radar charts. The respondents representing municipalities provided answers on a three-point scale, where 1 meant that the given issue did not occur and 3 meant that the phenomena was very intense. The purpose of the synthetic presentation of data in diagrams is to present the arithmetic averages of the response value, whereas in-depth analyses were carried out on raw data.

Figure 2.

The persistence of selected social issues in the analysed municipalities depending on the demographic structure.

Figure 3.

The prevalence of selected social problems in the analysed municipalities depending on the type of municipality.

Figure 4.

The prevalence of selected social issues in the analysed municipalities depending on the assessment of intensity of the ageing process.

Analysis of Figure 2 indicates the existence of differences in the assessment of particular social issues. The researched entities pointed to issues related to the occurring demographic processes, with unemployment, alcoholism, poverty, violence and migration process being some of the most important ones. However, taking into account the demographic structure of municipalities and their division into old and young municipalities, there are some differences in the assessment of the prevalence of these issues. The biggest discrepancies are visible in the assessment of demographic processes, which are much more widely perceived in the first group of municipalities. This is confirmed by previous observations according to which old municipalities assessed the extent of the prevalence of the ageing process as being high or rather high much more frequently. Differences in the assessment of the occurrence of social issues are also visible in the case of homelessness. This issue is more common in old municipalities than in young ones. However, younger municipalities more often indicate the occurrence of human migration. It is worth noting that long-term migration processes can lead to a change in the municipalities’ demographic structure, which will result in the intensification of issues characteristic of old municipalities.

Assuming the type of a municipality as a criterion, there is a markedly greater variation in the assessment of the severity of particular social issues than in the case of division into old and young municipalities (Figure 3). In particular, cities with poviat rights stand out; in their opinion, demographic processes and homelessness are more noticeable than in other types of municipalities. In turn, problems related to human migrations, low participation in cultural and public life, and low level of education are clearly moved to the background. In the case of other areas, their degree of intensification is similar for all types of entities studied. However, it should be noted that the most noticeable issues are social issues such as: alcoholism, unemployment, human migration, violence, poverty, and unfavourable demographic processes. All types of researched municipalities assessed that these issues occur at an increased level.

Figure 4 illustrates the occurrence of particular social issues against the background of subjective assessment of the intensity of the process of population ageing. The exceptionally high importance attributed to issues related to unfavourable demographic processes by municipalities assessing the degree of population ageing should not be surprising. It testifies to the good identification of existing issues by these entities. In municipalities which assessed the intensity of demographic processes as high, issues accompanying this phenomenon include above all social inequalities, alcoholism, unemployment, poverty and violence. These municipalities also indicate issues related to human migration. However, it is worth noting that in entities with high intensity of population ageing, issues related with low participation in public and cultural life occur relatively low. It can therefore be assumed that seniors form part of a population that is has an above-average level of engagement in the public and cultural life of local communities.

In the second stage of the study, an attempt was made to identify the biggest challenges related to population ageing in the municipalities of the Małopolska Voivodeship. To this end, based on the conducted epistemological analyses and review of current research in this area, 11 potential threats to LGUs resulting from the ageing process were identified and municipalities were asked to assess them on a three-point scale, where 1 meant that the given issue would not be a problem, and 3 meant that it would be a significant problem. A summary of the responses given in the breakdown into the three sections of the municipalities discussed above is shown in Figure 5. Similarly to for the analysis of current issues, for the purposes of a demonstrative presentation of the challenges for local government units in relation to ageing, the figure shows the arithmetic averages of responses given, and in-depth analyses were carried out on raw data. Table 4 summarises the statistical significance of observed differences in the assessment of individual threats in the analysed municipalities. The non-parametric Chi-square test verified the null hypothesis in relation to the equality of response distributions in individual cross-sections of the analysed municipalities.

Figure 5.

Surveyed municipalities opinion on the challenges related to the population ageing by demographic structure, type of municipality and subjective assessment of the intensity of the ageing process. Note: [1] Lack of adequate financial resources for the implementation of these tasks; [2] Lack of qualified employees at the municipality office and organisational units; [3] Increased processes related to social exclusion of older people; [4] Maladjustment of local infrastructure to the needs of older people; [5] The deteriorating situation on the local labour market due to the decline in the number of people at working age; [6] Decrease in municipality income; [7] Decrease of family care potential; [8] Reduction in the economic potential of the municipality [9] Increased health care costs; [10] Increase in the cost of institutional care; [11] Increased costs of community care.

Table 4.

The challenges related to population ageing in different types of local government units (LGUs) by demographic structure, type of municipality, and subjective assessment of the intensity of the ageing process.

Analysing Figure 6, firstly it should be pointed out that the division by demographic structure does not differentiate the researched municipalities in terms of prevalence of individual challenges related to population ageing. Large differences were observed only in the areas of maladjustment of local infrastructure to the needs of older people, a deteriorating situation in the local labour market, a decrease in municipality income and a decrease in the family’s care potential. Only differences regarding the labour market situation were statistically significant (Table 4). Similarly, the division due to the type of JST does not clearly differentiate the entities examined—only in the case of an increase in healthcare costs are there grounds to reject the null hypothesis with an equal distribution of responses in the four groups studied.

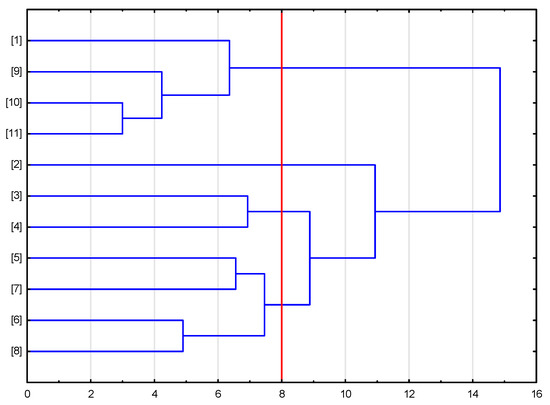

Figure 6.

Results of cluster analysis for threats of LGUs using the Ward method.

The division of the surveyed entities based on subjective assessment of demographic changes leads to the conclusion that the perception of the occurrence of individual issues depends on the assessment of the intensity of population ageing. Therefore, this means that depending on the perception of intensification of demographic changes, municipalities identify challenges related to this process differently. As a rule, municipalities that perceive the occurring changes to a greater extent point to greater individual issues. For example, municipalities assessing the ageing process as being rapid assign greater importance to challenges such as: a deteriorating situation in the local labour market, a decrease in municipality income, shrinking family care potential; a reduction in the economic potential of the municipality; and increases in the costs of community care. These observations are also confirmed by the verification of statistical hypotheses about the equality of response distributions in the studied groups of municipalities (Table 4).

In the next step of the research, an attempt to group major threats that co-occur in the analysed municipalities was made. To do so, the Ward’s hierarchical clustering method was applied. This method aims to minimize the sum of squares of deviations of any two clusters that can be formed at any stage (Ward 1963). As a measure of distance between considered objects with the standard Euclidean distance was adopted. In the study, the algorithm aimed to group eleven of the aforementioned variables into the larger clusters. The performed analysis leads to distinguishing several groups of threats that seem to co-occur in the analysed municipalities (cf. Figure 6). These areas are:

- Area 1: [9] increase in healthcare costs, [10] increase in the cost of institutional care; [11] increased costs of community care; and [1] lack of adequate resources for the realisation of tasks involving provision of these services.

- Area 2: [5] a deteriorating situation in the local labour market; [7] a reduction of the family care potential; [6] a decrease of the municipality’s income; and [8] a reduction in the economic potential of the municipality.

- Area 3: [3] maladjustment of local infrastructure to the needs of older people; [4] intensification of processes related to social exclusion of older people.

Moreover, as an independent factor distinguished can be [2] the lack of qualified employees in the municipality office and organisational units.

In light of the LGU tasks discussed in the context of the elderly’s needs (see Table 2), the problems highlighted in the first area will be particularly visible in the case of tasks related to long-term care and health protection. Problems occurring in the second area will be reflected first of all in municipal budgets on the revenue side, but also on the expenditure side, which will result from the necessity of LGUS’ greater involvement in the area of elderly care, which until now has been the domain of the family. The third area is connected with tasks in the field of culture, social activation of older people, and providing infrastructure adapted to the needs and capabilities of the elderly. On the other hand, the separately distinguished area related to lack of qualified employees in the municipality’s office and organisational units testifies to the need for educational activities for the education of personnel and society.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The occurring demographic changes are reflected in practically all areas of LGUs’ activity, and their results are visible particularly in areas related to the realisation of municipalities’ own tasks aimed at fulfilling the basic needs of the local community. According to the epistemological analyses carried out, these areas include, in particular, long-term care, including social welfare and health care, education, culture, social activation of seniors, and local infrastructure. The empirical studies of the authors presented in the study allowed for a detailed diagnosis of the currently occurring problems related to population ageing, as well as the identification of the key challenges for this main issue. In the context of the issues raised, it should also be noted that in the long-term, the intensification of the ageing process will mean not only an intensification of social issues, but also a significant increase in the costs of tasks related to meeting the needs of older people.

From the conducted research, the results show that only a few municipalities, mainly larger and more urbanised, see the key importance of the intensity of the ageing process (33% of cities with poviat rights, 14% of municipalities and only 4% of rural municipalities). It should also be noted that in municipalities with a higher percentage of elderly residents, the awareness of ongoing changes is generally higher than in younger municipalities. Potentially, the biggest threat connected with demographic changes is a lack of awareness about the occurrence of these issues. It is impossible to effectively counteract unidentified threats.

Regardless of the division criterion applied, all the analysed municipalities indicate a similar catalogue of the most important social issues. These include in particular: demographic processes (indicated as being significant by 71% of municipalities), human migrations (76%), unemployment (88%), alcoholism (93%), and poverty (75%). To a lesser extent, these include issues such as: deficits in the level of education (15%) and social capital (36%), as well as participation in public (31%) and cultural life (34%). However, it should be noted that due to the applied research methodology, the indicated catalogue of social issues may be a reflection of the subjective view at the priorities related to the local policy, and not necessarily the actual intensity of particular issues.

Studies of the Małopolska municipalities indicate that in the light of the diagnosis of current issues, the greatest challenges associated with an ageing population are related to the lack of adequate financial resources (a significant problem for 60% of municipalities), a decrease in municipality income (38%), a deteriorating situation in the local labour market (38%), decreased family care potential (38%), increased healthcare costs (65%), and community care costs (62%). It follows that from the municipal point of view, the consequences of an aging population will not only have a financial dimension, but will also require a certain redefinition in the scope of the catalogue of tasks to be carried out. It should be remembered that the aging process is also accompanied by other civilisation processes, resulting inter alia in the change of the family model and way of life, which in turn leads to increasing municipal responsibility for this social group in the context of satisfying the needs of the elderly. Increasing life expectancy (double aging) also enforces the need to provide care and health services to a wider group of seniors.

Although the issues raised in the study are based on Polish experiences, the conclusions drawn from the conducted analyses have also a broader international context. The tasks implemented in individual countries by the local governments are aimed at providing access to basic goods and services for local communities. Despite the fact that there are visible differences in the structures of local governments in EU countries, in the way their tasks are implemented, or in the sources of their financing, the scope of implemented activities is comparable and subordinated to satisfy collective needs. The problems and conditions for the implementation of tasks and challenges facing local government are also similar. This is due to the two main reasons. First, almost 60% of the decisions taken by towns and regions are influenced by European legislation. European directives and regulations, in fields such as transport, environmental protection, or public procurement are frequently addressed to local authorities. Furthermore, LGUs have a specific voice in the decision-making process of the EU (e.g., Committee of the Regions and some of the European Parliament special committees) and take part in the implementation of several cohesion and structural funds (Moreno 2012). Second, the results of economic, political, and social problems are common to all of the EU member states. One such example of this is demographic changes, the effects of which are visible throughout the EU.

Finally, it is worth noting that the conducted research can constitute the basis for further in-depth analyses. For the theoretical aspect, considerations regarding the development of the sector of services targeted at the elderly as part of silver economy seem to be interesting. It may well be contemplated how local government units should create local policy in order to use the potential resulting from this sector of the economy. It is also worth verifying the formulated conclusions based on research in other voivodeships and at an international scale, analysing the experiences in other countries. It also seems interesting to examine what specific activities carried out by municipalities that are considered desirable through the prism of older people. Looking at the issue of local government units’ tasks from a slightly different angle, it is also worth attempting to precisely determine the financial consequences of demographic changes for LGUs, which, however, is a time-consuming and complicated task due to the current legal conditions related to drawing up a budget.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.J. and K.M.-W.; methodology, T.J. and K.M.-W.; validation, T.J. and K.M.-W.; formal analysis, T.J. and K.M.-W.; investigation, T.J. and K.M.-W.; resources, T.J. and K.M.-W.; data curation, T.J. and K.M.-W.; writing—original draft preparation, T.J. and K.M.-W.; writing—review and editing, T.J. and K.M.-W.; visualization, T.J. and K.M.-W.; funding acquisition, T.J. and K.M.-W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project has been financed by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education within the “Regional Initiative of Excellence” Programme for 2019-2022. Project no.: 021/RID/2018/19. Total financing: 11 897 131,40 PLN.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aigner-Walder, Birgit, and Thomas Döring. 2012. The Effects of Population Ageing on Private Consumption—A Simulation for Austria Based on Household Data up to 2050. Eurasian Economic Review 2: 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, Maria. 2018. Fighting Depopulation in Portugal: Local and Central Government Policies in Times of Crisis. Portuguese Journal of Social Science 17: 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arber, Sara, and Nigel Gilbert. 1989. Transitions in Caring: Gender, Life Course and the Care of the Elderly. In Becoming and Being Old. Sociological Approach to Later Life. Edited by William Bytheway. London: Sage, pp. 72–93. [Google Scholar]

- Arltová, Markéta, Luboš Smrčka, Jana Vrabcova, and Jaroslav Schönfeld. 2016. The Ageing of the Population in Developed Countries—the Economic Consequences in the Czech Republic. Economics & Sociology 9: 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audit Commission. 2009. Financial Implications for Local Authorities of an Ageing Population. Policy and Literature Review; London: Audit Commision. Available online: https://www.bl.uk/britishlibrary/~/media/bl/global/social-welfare/pdfs/non-secure/f/i/n/financial-implications-for-local-authorities-of-an-ageing-population-policy-and-literature-review-local-government.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2020).

- Baltes, Paul B., Karl Ulrich Mayer, Hanfried Helmchen, and Elisabeth Steinhagen-Thiessen. 1993. The Berlin Aging Study (BASE): Overview and Design. Ageing & Society 13: 483–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, Alain, Yves Carrière, and Patrick Sabourin. 2016. Understanding Employment Participation of Older Workers: The Canadian Perspective. Canadian Public Policy 42: 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, Jillian, and David N. Weil. 2015. Old Teachers, Old Ideas, and the Effect of Population Aging on Economic Growth. Research in Economics 69: 661–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bień, Barbara. 2008. Opieka Zdrowotna Nad Ludźmi w Starszym Wieku. Stan a Potrzeby w Perspektywie Starzenia Się Ludności Polski. Biuletyn Rządowej Rady Ludnościowej 53: 128–48. [Google Scholar]

- Błędowski, Piotr. 2002. Lokalna Polityka Społeczna Wobec Ludzi Starych. Warszawa: Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, David E., and Dara Lee Luca. 2016. Chapter 1—The Global Demography of Aging: Facts, Explanations, Future. In Handbook of the Economics of Population Aging. Edited by John Piggott and Alan Woodland. North-Holland: Amsterdam, vol. 1, pp. 3–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, David E., David Canning, and Günther Fink. 2010. Implications of Population Ageing for Economic Growth. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 26: 583–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börsch-Supan, Axel. 2003. Labor Market Effects of Population Aging. Labour 17: 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börsch-Supan, Axel, Klaus Härtl, and Alexander Ludwig. 2014. Aging in Europe: Reforms, International Diversification and Behavioral Reactions. MEA Discussion Paper Series 201425. Munich Center for the Economics of Aging (MEA) at the Max Planck Institute for Social Law and Social Policy. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/meameawpa/201425.htm (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- Brubaker, Timothy H. 1987. Aging, Health, and Family: Long-Term Care. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, Bernard. 1983. Work or Retirement?: Labour Market and Social Policy for Older Workers in France, Great Britain, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the USA. Aldershot: Gower Pub Co. [Google Scholar]

- Ciesielska, Monika, and Patrycja Paryna. 2013. Demografia a System Emerytalny. Wrocław: Centrum Analiz Stowarzyszenia KoLiber. Available online: https://analizy.koliber.org/files/2014/11/Wersja-ostateczna-raportu-pdf-2.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2020).

- Coleman, Andrew. 2014. Squeezed in and Squeezed out: The Effects of Population Ageing on the Demand for Housing. Economic Record 90: 301–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Ministers. 2018. Uchwała Nr 161 Rady Ministrów z Dnia 26 Października 2018 r. w Sprawie Przyjęcia Dokumentu Polityka Społeczna Wobec Osób Starszych 2030. Bezpieczeństwo—Uczestnictwo—Solidarność. M.P. 2018, poz. 1169. Warszawa: Rada Ministrów. [Google Scholar]

- de Albuquerque, Paula Cristina A. Mateus. 2018. Population Ageing and the Labour Market during the Recent Crisis in Portugal. Portuguese Journal of Social Science 17: 105–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobosz, Piotr. 2007. Komentarz Do Ustawy o Samorządzie Gminnym. Edited by Paweł Chmielnicki. Warszawa: LexisNexis. [Google Scholar]

- Economic Policy Committee. 2003. The Impact of Ageing Populations on Public Finances: Overview of Analysis Carried out at EU Level and Proposals for a Future Work Programme. EPC/ECFIN/435/. Brussels: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Eggertsson, Gauti B., Manuel Lancastre, and Lawrence H. Summers. 2018. Aging, Output Per Capita and Secular Stagnation. 24902. NBER Working Papers. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/nbr/nberwo/24902.html (accessed on 30 March 2020).

- European Commission. 2018. The 2018 Ageing Report: Economic and Budgetary Projections for the EU Member States (2016–2070). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/economy-finance/2018-ageing-report-economic-and-budgetary-projections-eu-member-states-2016-2070_en (accessed on 30 March 2020).

- Ferguson, Brian S. 1986. Labour Force Substitution and the Effects of an Ageing Population. Applied Economics 18: 901–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilowska, Zyta, Dariusz Kijowski, Ryszard Kulesza, Wojciech Misiąg, Stanisław Prutis, Mirosław Stec, Jacek Szlachta, and Janusz Zaleski. 2002. Podstawy prawne funkcjonowania terytorialnej administracji publicznej w RP. Samorząd Terytorialny 1–2: 19–220. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Jonathan, and Stijn Hoorens. 2006. The New Pronatalism, The Policy Consequences of Population Ageing. Public Policy Research 13: 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUS. 2014. Population Forecast for 2014–2050, Studies and Statistical; Warszawa: Główny Urząd Statystyczny.

- GUS. 2018. Gospodarka Senioralna w Polsce—Stan i Metody Pomiaru; Prace Studialne. Warszawa: Główny Urząd Statystyczny.

- GUS. 2019. Life Expectancy Tables of Poland 2018; Statistical Analyses. Warszawa: Główny Urząd Statystyczny.

- Hobman, David, ed. 1978. The Social Challenge of Ageing. London: Croom Helm. [Google Scholar]

- Hyun, Kyung-Rae, Sungwook Kang, and Sunmi Lee. 2016. Population Aging and Healthcare Expenditure in Korea. Health Economics 25: 1239–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, Philipp, and Torsten Schmidt. 2016. The Political Economy of Public Investment When Population Is Aging: A Panel Cointegration Analysis. European Journal of Political Economy 43: 145–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłobukowska, Justyna. 2014. Polityka mieszkaniowa wobec starzenia się społeczeństw – podstawowe wyzwania, Mieszkalnictwo, Świat Nieruchomości. World of Real Estate Journal 89: 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalik, Stanisław. 2006. Pedagogiczne Problemy Funkcjonowania i Opieki Osób w Starszym Wieku. In Pedagogika Specjalna. Edited by Władysław Dykcik. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM. [Google Scholar]

- Kurzynowski, Adam. 1999. Polityka Społeczna—Warunki Realizacji i Skuteczność. In Teoretyczne Problemy Nauki o Polityce Społecznej. Edited by Julian Auleyter and Jan Danecki. Warszawa: Elipsa. [Google Scholar]

- Kuś, Małgorzata, and Magdalena Szwed. 2012. Realizacja Potrzeb Ludzi Starszych a Zadania Samorządu Terytorialnego. Special Issue. Prace Naukowe Akademii Im. Jana Długosza w Częstochowie. Seria Res Politicae, 308–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, Tony. 2016. How the Ageing Population Contributes to UK Economic Activity: A Microsimulation Analysis. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 63: 497–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Hyun-Hoon, and Kwanho Shin. 2019. Nonlinear Effects of Population Aging on Economic Growth. Japan and the World Economy 51: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Hyun-Hoon, Kwanho Shin, and Donghyun Park. 2017. Population Aging and Its Impact on Economic Growth -Implications for Korea. Economic Analysis 196: 162–88. [Google Scholar]

- Leśna-Wierszołowicz, Elwira. 2018. The Consequences of Ageing Society in Poland. Studia i Prace WNEiZ US 51: 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, Piotr, and Jan Rutkowski, eds. 2017. Starzenie Się Ludności, Rynek Pracy i Finanse Publiczne w Polsce. Warszawa: Przedstawicielstwo Komisji Europejskiej w Polsce. [Google Scholar]

- Lisenkova, Katerina, Marcel Mérette, and Robert Wright. 2013. Population Ageing and the Labour Market: Modelling Size and Age-Specific Effects. Economic Modelling 35: 981–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Local and Regional Governments in Europe. 2016. Structures and Competences. Brussels: Council of European Munincipalities and Regions. [Google Scholar]

- Local Government Association. 2015. Ageing: The Silver Lining. The Opportunities and Challenges of an Ageing Society for Local Government; London: Local Government Association. Available online: https://www.local.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/ageing-silver-lining-oppo-1cd.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Lutz, Wolfgang, Warren Sanderson, and Sergei Scherbov. 2008. The Coming Acceleration of Global Population Ageing. Nature 451: 716–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestas, Nicole, Kathleen J Mullen, and David Powell. 2016. The Effect of Population Aging on Economic Growth, the Labor Force and Productivity. Working Paper 22452. Working Paper Series. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maj-Waśniowska, Katarzyna. 2018. Contemporary Demographic Challenges for the Education System in Poland in Comparison with Other Countries of the European Union. In International Relations 2018: Current Issues of World Economy and Politics. Conference Proceedings 19th International Scientific Conference Smolenice Castle. Bratislava: Publishing Ekonóm, University of Economics in Bratislava, Faculty of International Relations. [Google Scholar]

- Małecka, Barbara. 1985. Elementy Gerontologii Dla Pedagogów. Gdańsk: Uniwersytet Gdański. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowska-Misiąg, Elżbieta, and Wojciech Misiąg. 2014. Finanse Publiczne w Polsce. LexisNexis: Warszawa. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, Angel-Manuel. 2012. Local Government in the Member States of the European Union: A Comparative Legal Perspective. Madrid: National Institute of Public Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer, Jill. 2014. Local Government’s Role in Responding to an Ageing Population. Age UK. Available online: http://www.cpa.org.uk/cpa-lga-evidence/Age_UK/LGACallEvidenceLArole(Age%20UK).pdf (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- Nagarajana, Renuga N., Aurora A. C. Teixeira, and Sandra T. Silva. 2016. The Impact of an Ageing Population on Economic Growth: An Exploratory Review of the Main Mechanisms. Análise Social 51: 4–35. [Google Scholar]

- Narciso, Alexandre. 2010. The Impact of Population Ageing on International Capital Flows. 26457. MPRA Paper. Munich: University Library of Munich. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/pra/mprapa/26457.html (accessed on 29 March 2020).

- O’Brien, Elizabeth. 2014. Planning for Population Ageing: Ensuring Enabling and Supportive Physical-Social Environments—Local Infrastructure Challenges. Planning Theory & Practice 15: 220–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prettner, Klaus. 2013. Population Aging and Endogenous Economic Growth. Journal of Population Economics 26: 811–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racław, Mariola, and Magdalena Rosochacka-Gmitrzak. 2013. Proces Starzenia Się, w Kontekście Wyzwań Demografii, Polityki Społecznej Oraz Doniesień Badawczych. Projekt Aktywny senior—najlepszy rzecznik swoich społeczności. Warszawa: WRZOS, MPiPS. [Google Scholar]