Life Cycle Assessment of an Innovative Biogas Plant: Addressing Methodological Challenges and Circular Economy Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

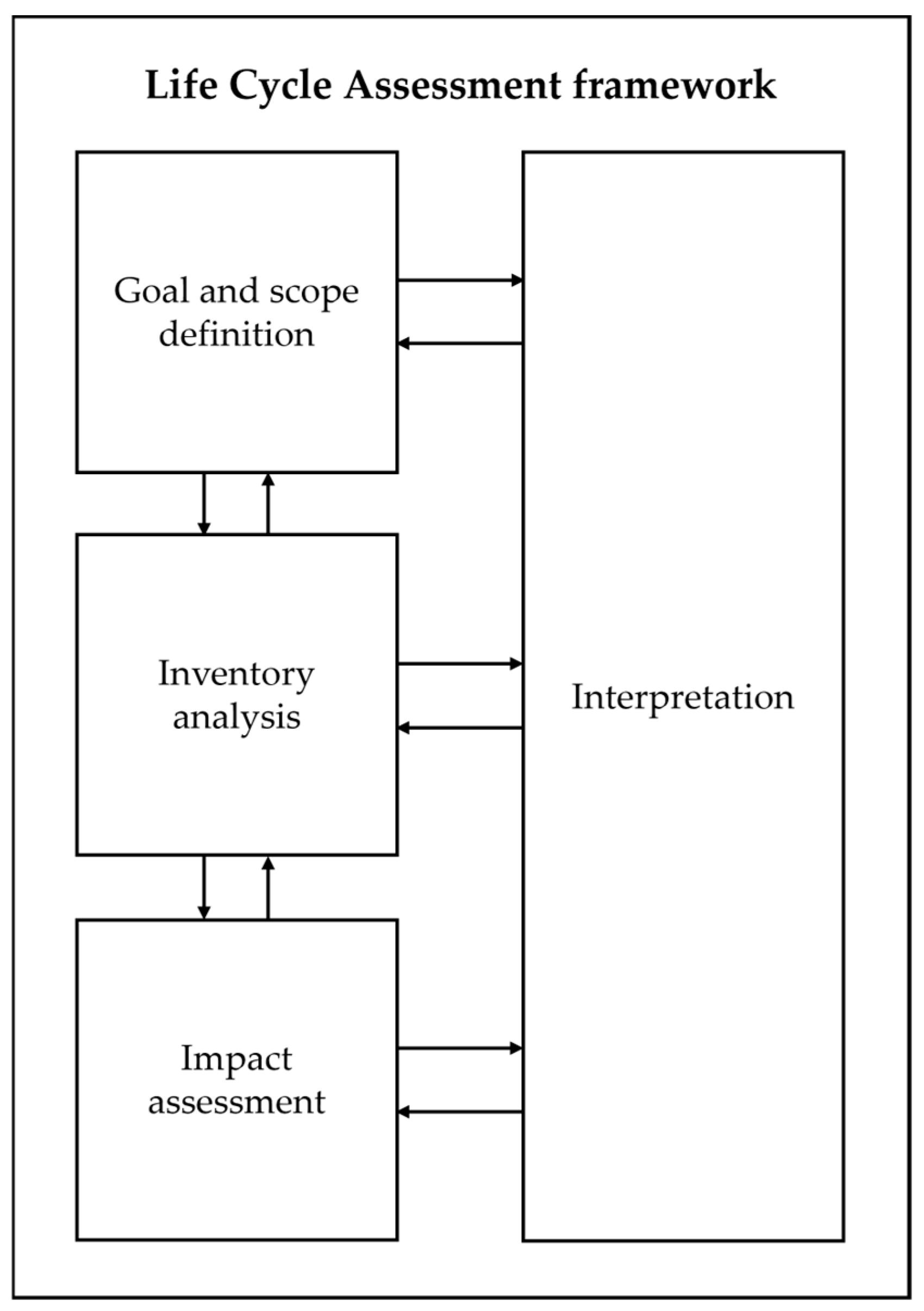

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Goal of the Study

2.2. Scope of the Study

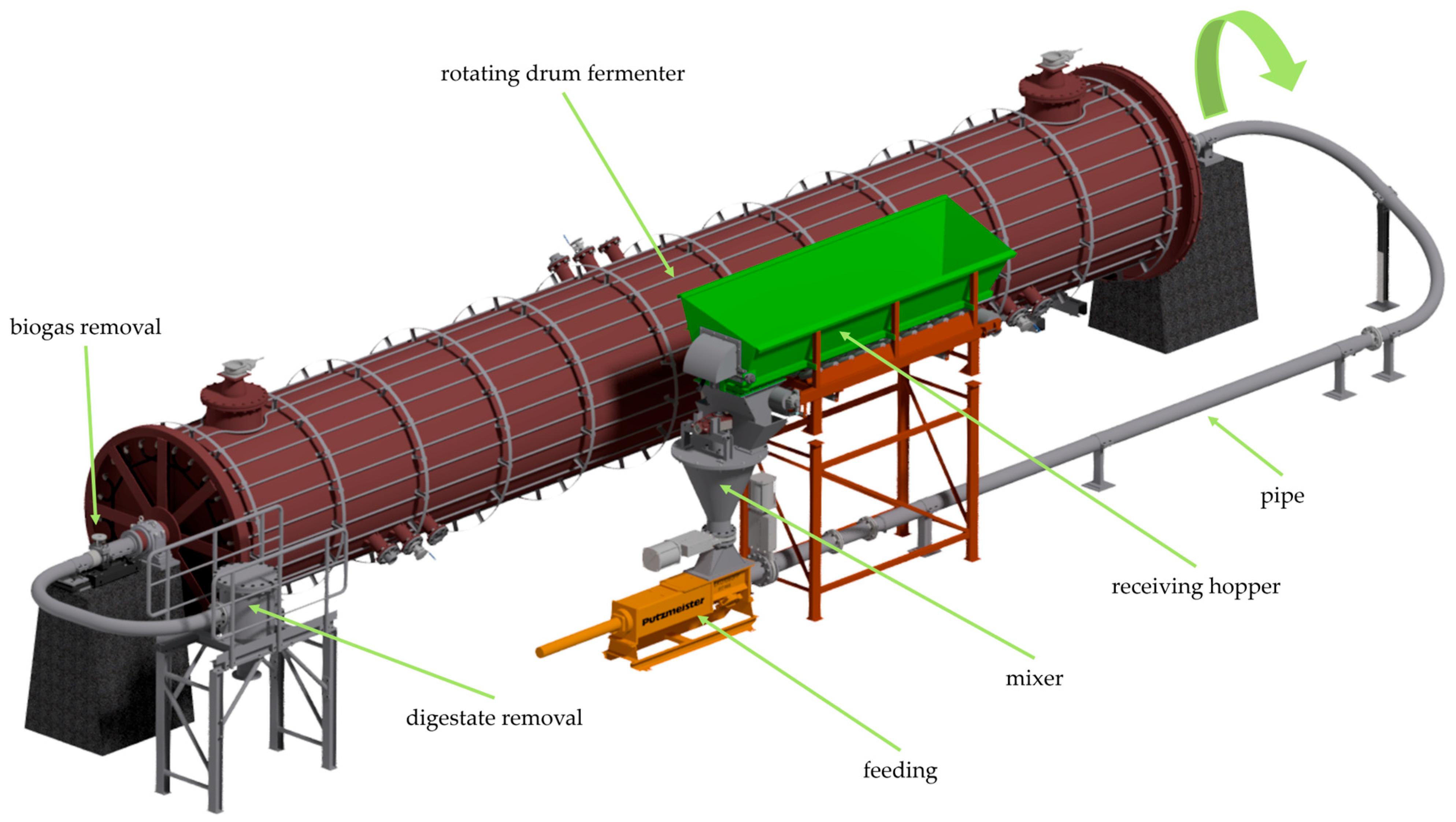

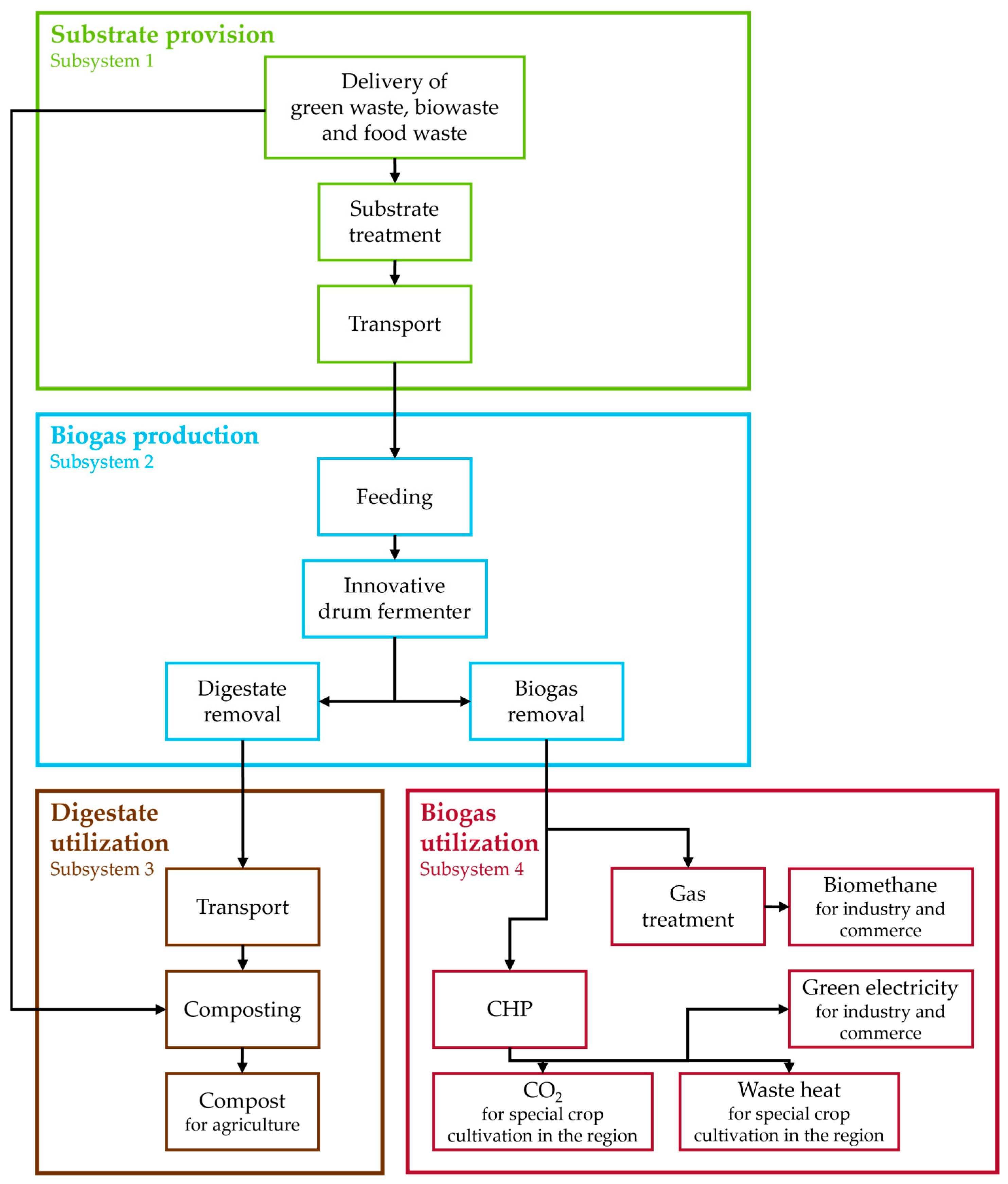

2.2.1. Product System: Biogas Plant

2.2.2. Functional Unit

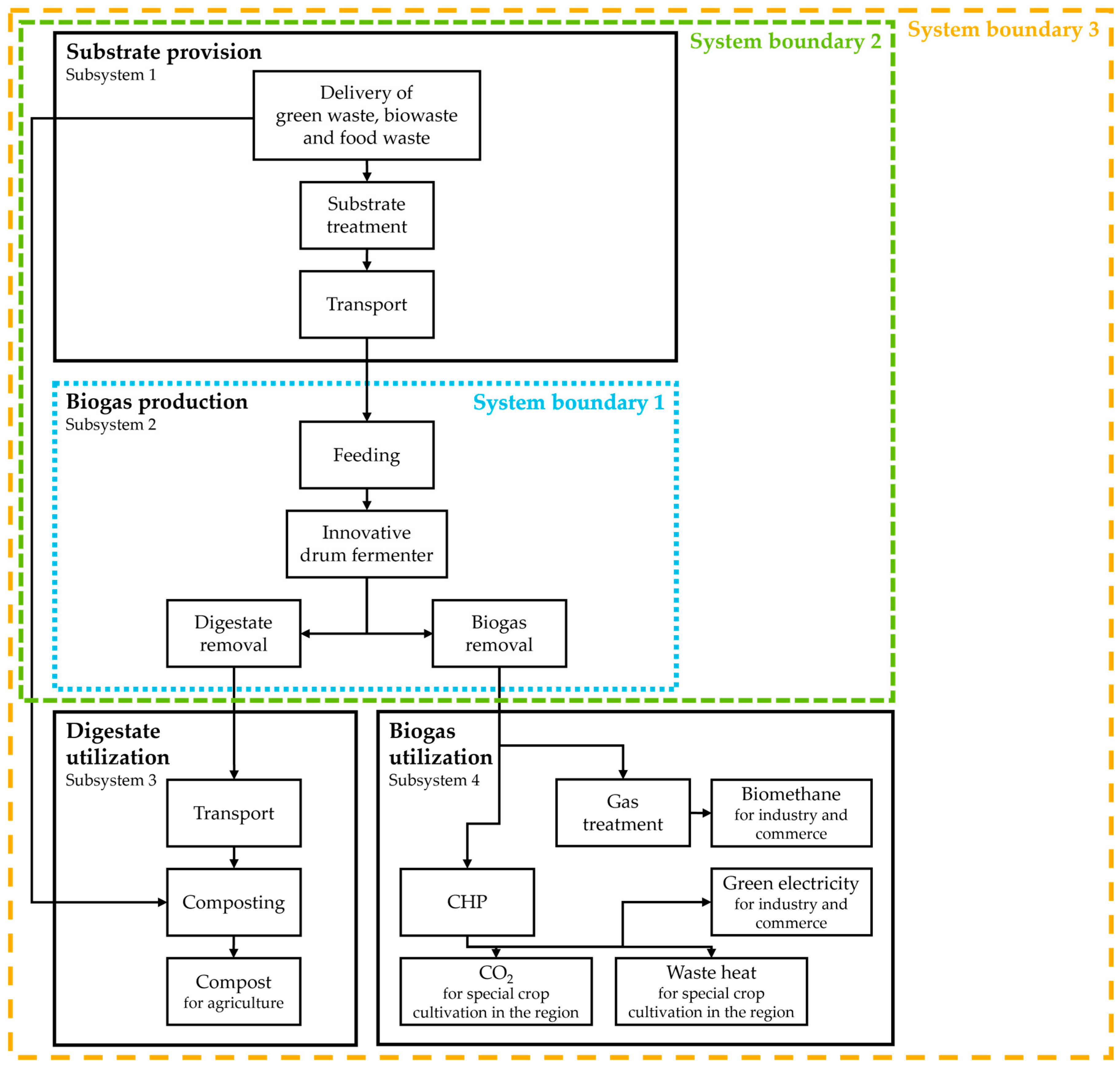

2.2.3. System Boundaries

2.2.4. Allocation Procedure

2.2.5. Impact Assessment

2.2.6. Data Sources and Data Quality

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Umweltbundesamt. Grundlagen des Klimawandels. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/themen/klima-energie/grundlagen-des-klimawandels (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Umweltbundesamt. Klima und Treibhauseffekt. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/themen/klima-energie/klimawandel/klima-treibhauseffekt (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Umweltbundesamt. Klima- und Ressourcenschutz: Beides ist möglich. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/themen/klima-ressourcenschutz-beides-ist-moeglich (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Europäisches Parlament. Reduktion von CO2-Emissionen: Ziele und Maßnahmen der EU. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/de/article/20180305STO99003/reduktion-von-co2-emissionen-ziele-und-massnahmen-der-eu#klimaziele-der-eu-und-der-europische-grne-deal-4 (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Bundesregierung. Klimaschutzgesetz und Klimaschutzprogramm: Ein Plan fürs Klima. Available online: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/aktuelles/klimaschutzgesetz-2197410 (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Destatis. Europäischer Green Deal: Ziele, Daten und Fakten 2023. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/Europa/DE/Thema/GreenDeal/_inhalt.html (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- European Commission. The European Green Deal: A Growth Strategy That Protects the Climate. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/stories/european-green-deal/ (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Bundesregierung. Transformation Gemeinsam Gerecht Gestalten: Deutsche Nachhaltigkeitsstrategie: Weiterentwicklung 2025. 2025. Available online: https://www.bundesregierung.de/resource/blob/975274/2335292/c4471db32df421a65f13f9db3b5432ba/2025-02-17-dns-2025-data.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Gesetz für den Ausbau Erneuerbarer Energien (Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetz): EEG 2023. 2014. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/eeg_2014/EEG_2023.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Gesetz zur Förderung der Kreislaufwirtschaft und Sicherung der Umweltverträglichen Bewirtschaftung von Abfällen (Kreislaufwirtschaftsgesetz): KrWG. 2012. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/krwg/KrWG.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- BMWK; BMEL; BMUV. Eckpunkte für eine Nationale Biomassestrategie (NABIS). 2022. Available online: https://www.bmleh.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/_Landwirtschaft/Nachwachsende-Rohstoffe/eckpunkte-nationale-biomassestrategie-nabis.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- BMUV. Bundeskabinett Verabschiedet Nationale Kreislaufwirtschaftsstrategie. [Press Release]. Available online: https://www.bmuv.de/pressemitteilung/bundeskabinett-verabschiedet-nationale-kreislaufwirtschaftsstrategie (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Europäisches Parlament. Kreislaufwirtschaft: Definition und Vorteile. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/de/article/20151201STO05603/kreislaufwirtschaft-definition-und-vorteile (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Directive (EU) 2018/851 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 Amending Directive 2008/98/EC on Waste: Waste Framework Directive. 2008. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32018L0851 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Umweltbundesamt. Bioabfälle. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/daten/ressourcen-abfall/verwertung-entsorgung-ausgewaehlter-abfallarten/bioabfaelle (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Britz, W.; Delzeit, R. The impact of German biogas production on European and global agricultural markets, land use and the environment. Energy Policy 2013, 62, 1268–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theuerl, S.; Herrmann, C.; Heiermann, M.; Grundmann, P.; Landwehr, N.; Kreidenweis, U.; Prochnow, A. The Future Agricultural Biogas Plant in Germany: A Vision. Energies 2019, 12, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMWK. Aktualisierung des Integrierten Nationalen Energie- und Klimaplans. 2024. Available online: https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Energie/20240820-aktualisierung-necp.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- European Commission. A Sustainable Bioeconomy for Europe: Strengthening the Connection Between Economy, Society and the Environment: Updated Bioeconomy Strategy. 2018. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/792130 (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Malet, N.; Pellerin, S.; Girault, R.; Nesme, T. Does anaerobic digestion really help to reduce greenhouse gas emissions? A nuanced case study based on 30 cogeneration plants in France. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 384, 135578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN EN ISO 14040; Deutsches Institut für Normung. Umweltmanagement—Ökobilanz—Grundsätze und Rahmenbedingungen. Beuth: Berlin, Germany, 2021.

- DIN EN ISO 14044; Deutsches Institut für Normung. Umweltmanagement—Ökobilanz—Anforderungen und Anleitungen. Beuth: Berlin, Germany, 2021.

- Geldermann, J.; Schmehl, M.; Rottmann-Meyer, M.L. Ökobilanzielle Bewertung von Biogasanlagen Unter Berücksichtigung der Niedersächsischen Verhältnisse. 2012. Available online: https://www.ml.niedersachsen.de/download/67480/Oekobilanzielle_Bewertung_von_Biogasanlagen_in_Nds._Georg-August-Universitaet_2012.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Aziz, N.I.H.A.; Gheewala, S.H.; Hanafiah, M.M. A review on life cycle assessment of biogas production: Challenges and future perspectives in Malaysia. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 122, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacenetti, J.; Sala, C.; Fusi, A.; Fiala, M. Agricultural anaerobic digestion plants: What LCA studies pointed out and what can be done to make them more environmentally sustainable. Appl. Energy 2016, 179, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, G.; Dhanorkar, M.; Kale, S.; Patil, Y.B. Life cycle assessment of anaerobic digestion systems: Current knowledge, improvement methods and future research directions. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2020, 31, 683–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijazi, O.; Munro, S.; Zerhusen, B.; Effenberger, M. Review of life cycle assessment for biogas production in Europe. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 1291–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morero, B.; Vicentin, R.; Campanella, E.A. Assessment of biogas production in Argentina from co-digestion of sludge and municipal solid waste. Waste Manag. 2017, 61, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankathi, S.K.; Chaudhari, U.S.; Handler, R.M.; Shonnard, D.R. Sustainability of Biogas Production from Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste and Animal Manure. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 4, 418–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawickrama, K.; Ruparathna, R.; Seth, R.; Biswas, N.; Hafez, H.; Tam, E. Challenges and Issues of Life Cycle Assessment of Anaerobic Digestion of Organic Waste. Environments 2024, 11, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-Ocaña, E.R.; Abendroth, C.; Domínguez, I.C.; Sánchez, A.; Dornack, C. Life cycle assessment of biowaste and green waste composting systems: A review of applications and implementation challenges. Waste Manag. 2023, 171, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serafini, L.F.; Praça, P.J.G.M.; González-Andrés, F.; Gonçalves, A. Life cycle approach as a tool for assessing municipal biowaste treatment units: A systematic review. Waste Manag. Res. 2025, 43, 1509–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewerenz, S.; Sailer, G.; Pelz, S.; Lambrecht, H. Life cycle assessment of biowaste treatment—Considering uncertainties in emission factors. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2023, 15, 100651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyng, K.-A.; Modahl, I.S.; Møller, H.; Saxegård, S. Comparison of Results from Life Cycle Assessment when Using Predicted and Real-life Data for an Anaerobic Digestion Plant. J. Sustain. Dev. Energy Water Environ. Syst. 2021, 9, 1080373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garkoti, P.; Thengane, S.K. Techno-economic and life cycle assessment of circular economy-based biogas plants for managing organic waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 504, 145412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Technology Readiness Levels (TRL): Extract from Part 19—Commission Decision C(2014)4995. 2014. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/wp/2014_2015/annexes/h2020-wp1415-annex-g-trl_en.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Brück, F.; Theilen, U.; Weigand, H.; Geipert, S.; Geipert, H. Abschlussbericht Gärtrommel: Hessen ModellProjekte—LOEWE 3: KMU-Verbundvorhaben. [HA project no. 388/13-27, Unpublished]. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brück, F.; Theilen, U.; Weigand, H.; Geipert, S.; Geipert, H. Abschlussbericht BioTrom: Hessen ModellProjekte—LOEWE 3: KMU-Verbundvorhaben. [HA project no. 451/14-41, Unpublished]. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Klöpffer, W.; Grahl, B. Ökobilanz (LCA): Ein Leitfaden für Ausbildung und Beruf; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Timonen, K.; Sinkko, T.; Luostarinen, S.; Tampio, E.; Joensuu, K. LCA of anaerobic digestion: Emission allocation for energy and digestate. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 1567–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesohl, S. Analyse und Bewertung der Nutzungsmöglichkeiten von Biomasse: Untersuchung im Auftrag von BGW und DVGW; Band 1: Gesamtergebnisse und Schlussfolgerungen; Wuppertal Institut: Wuppertal, Germany, 2006; Available online: https://epub.wupperinst.org/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/2274/file/2274_Nutzung_Biomasse.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Poeschl, M.; Ward, S.; Owende, P. Environmental impacts of biogas deployment—Part II: Life cycle assessment of multiple production and utilization pathways. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 24, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehl, T.; Müller, J. Life cycle assessment of biogas digestate processing technologies. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 56, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufvesson, L.M.; Lantz, M.; Börjesson, P. Environmental performance of biogas produced from industrial residues including competition with animal feed—Life-cycle calculations according to different methodologies and standards. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 53, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.K.V.; Vu, D.Q.; Jensen, L.S.; Sommer, S.G.; Bruun, S. Life Cycle Assessment of Biogas Production in Small-scale Household Digesters in Vietnam. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 28, 716–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistisches Bundesamt. 14,4 Millionen Tonnen Bioabfälle im Jahr 2020. [Press Release]. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2022/09/PD22_371_321.html (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Buxmann, K.; Chudacoff, M.; Frischknecht, R.; Hellweg, S.; Müller-Fürstenberger, G.; Schmidt, M. Ökobilanz-Allokationsmethoden: Modelle aus der Kosten- und Produktionstheorie Sowie Praktische Probleme in der Abfallwirtschaft. Unterlagen zum 7. Diskussionsforum Ökobilanzen vom 24. Juni 1998 an der ETH Zürich, 1998. Available online: http://www.lcaforum.ch/Portals/0/DF_Archive/DF%201%20bis%2012/df7.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Rosenberger, S.; Wawer, T.; Heiker, M.; Mertins, A.; Fedler, M.; Witte, A.; Große-Kracht, I. Regionalanalyse und Entwicklung von Geschäftsmodellen für Einen Post-EEG-Betrieb von Biogasanlagen auf Basis von Rest- und Abfallstoffen. Abschlussbericht, 2023. Available online: https://opac.dbu.de/ab/DBU-Abschlussbericht-AZ-34663_01-Hauptbericht.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Research Institute for Sustainability. Methane: A Short-Lived Gas with Far-Reaching Effects. Available online: https://www.rifs-potsdam.de/en/blog/2024/04/methane-short-lived-gas-far-reaching-effects (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Götz, M.; Drechsler, F.; Krebs, J.-M.; von Gagern, S. Einführung Klimamanagement: Schritt für Schritt zu Einem Effektiven Klimamanagement in Unternehmen. 2017. Available online: https://www.ihk-muenchen.de/ihk/Klimapolitik/Klimamanagement-Schritt-f%C3%BCr-Schritt-einf%C3%BChren_GCN.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- iPoint-systems gmbh. Umberto: Experten LCA-Software für Professionelle Ökobilanzen. Available online: https://www.ipoint-systems.com/de/software/umberto/ (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Igos, E.; Benetto, E.; Meyer, R.; Baustert, P.; Othoniel, B. How to treat uncertainties in life cycle assessment studies? Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2019, 24, 794–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.-C.; Ma, H.; Lo, S.-L. Quantifying and reducing uncertainty in life cycle assessment using the Bayesian Monte Carlo method. Sci. Total Environ. 2005, 340, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Option 1: 1 kWh of Energy Generated | Option 2: 1 Ton of Biogenic Waste | |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Biogas as an energy source, electricity and/or heat production | Entire material flow, fermentation of biogenic waste into biogas and digestate |

| Objective | Investigation of the energy efficiency of the system, comparability with other energy sources | Assessment of the environmental impact of the entire system |

| System boundary | Processes contributing to energy generation, system expansion for digestate utilization | Holistic approach that considers all processes |

| Advantages |

|

|

| Limitations |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tscherney, H.-S.; Weigand, H.; Rohn, H. Life Cycle Assessment of an Innovative Biogas Plant: Addressing Methodological Challenges and Circular Economy Implications. Environments 2026, 13, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13020078

Tscherney H-S, Weigand H, Rohn H. Life Cycle Assessment of an Innovative Biogas Plant: Addressing Methodological Challenges and Circular Economy Implications. Environments. 2026; 13(2):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13020078

Chicago/Turabian StyleTscherney, Hannah-Sophie, Harald Weigand, and Holger Rohn. 2026. "Life Cycle Assessment of an Innovative Biogas Plant: Addressing Methodological Challenges and Circular Economy Implications" Environments 13, no. 2: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13020078

APA StyleTscherney, H.-S., Weigand, H., & Rohn, H. (2026). Life Cycle Assessment of an Innovative Biogas Plant: Addressing Methodological Challenges and Circular Economy Implications. Environments, 13(2), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13020078