Abstract

Leachates from municipal organic waste contain high concentrations of ammonium and organic matter, making their treatment a top priority. The present study addressed leachate treatment under nitrification and focused on the diversity and abundance of comammox bacteria and their interaction with other canonical microorganisms. Batch reactors (1L) were fed with synthetic (100 mg HN4+-N/L) or leachate ammonium and operated at 150 rpm, 3 mg DO/L, pH 7, and 30 °C. Reactor performance was evaluated using metabolic response variables and the microbial community by shotgun metagenomic sequencing. The results showed ammonium and organic matter (5200 mg COD/L) consumption efficiencies above 95%. The abundance and richness of the microbial community decreased in the presence of leachates. Sequences of the genus Nitrosomonas predominated with the synthetic medium, while the genus Nitrospira was the most abundant when fed with leachates. Archaea and anammox sequences were also detected. Comammox sequences of Candidatus Nitrospira inopinata, C. N. nitrificants, C. N. kreftii, C. N. neomarina, C. N. nitrosa, and C. N. allomarina were also detected, with the first species being predominant in the presence of leachates. These findings demonstrate that comammox and canonical microorganisms coexist during ammonium removal from leachates.

1. Introduction

An estimated 2.1 billion tons (BT) of municipal solid waste (MSW) were produced worldwide in 2020, and this number is predicted to grow to 3.8 BT by 2050 [1]. Managing MSW poses a major challenge, and a common practice is to dispose of this waste in sanitary landfills using poor engineering or open dumps, which results in significant damage to the environment and human health [2]. Municipal solid waste is mainly composed of organic matter, with a mean percentage of around 46%, although it usually varies between 40% and up to 60% depending on the socioeconomic conditions of each country [3]. The organic fraction can be transformed into various products of human interest, such as bioenergy production by anaerobic digestion and soil-amending biosolids via composting. Leachates comprise the liquid fraction resulting from the percolation of rainwater through MSW and the biodegradation of its organic fraction [4]. Organic solid waste usually contains high concentrations of heavy metals (higher than 2 mg/L), organic matter (chemical oxygen demand, COD, higher than 30,000 mg/L), and ammoniacal nitrogen (N-NH4+, between 500–2000 mg/L) [5,6,7]. Excessive levels of these compounds are highly contaminating and therefore require adequate treatment to reduce them. Leachates have been treated through the separate or combined application of nitrogen cycle-related microbial processes such as nitrification, denitrification, or anammox [8,9,10,11].

The application of the most appropriate treatment is based primarily on the chemical composition, which depends on the type of waste and the age of the landfill. For example, for the treatment of young leachate (<5 years) that has high concentrations of COD (>10,000 mg/L), ammonia nitrogen (>1000 mg/L), and a BOD5/COD ratio (between 0.5 and 1.0), the use of an aerobic process (e.g., constructed wetlands) may be effective, while for mature leachate (>10 years) that has low concentrations of COD (<4000 mg/L) and a BOD5/COD ratio (<0.1), the application of an anaerobic process (anammox process) could be more effective [12,13]. However, the prevailing recommendation in the literature is to implement a combination of physical, chemical, and biological processes to achieve more efficient results [14,15]. Among the physical-chemical processes that have been used are reverse osmosis, adsorption, filtration, air stripping, sedimentation, electrocoagulation, and Fenton [13,16,17]. For example, Smaoui et al. (2020) evaluated the combined process of air stripping, anaerobic digestion (AD), and aerobic activated sludge treatment for the treatment of landfill leachates [18]. The authors reported that the physical process removed 80% of ammonia and increased the carbon/nitrogen ratio to 25, proving suitable for the AD, which removed up to 81% of COD and, in conjunction with the aerobic treatment, removed up to 98% of the organic matter. Becerra et al. (2020) evaluated the coupling of a heterogeneous TiO2/UV photocatalysis system to an activated sludge reactor in the treatment of landfill leachates and reported that the biological process removed 38% of COD and 24% of dissolved organic carbon (DOC), while with the combined system, it was 68% and 76%, respectively [19]. The photocatalytic process generates reactive oxygen species such as hydroxyl radicals that favor the breaking down of recalcitrant compounds, facilitating their subsequent oxidation through biological processes [19,20].

Ammonium oxidation is an essential phase of the nitrogen cycle and was initially attributed to nitrification mediated by ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB) [21]. Anaerobic ammonium oxidation (ANAMMOX) was subsequently included, followed by ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) [22,23]. Nitrification carried out by two different microbial groups was accepted for over 100 years. However, in 2006, a theory was proposed suggesting that a single microorganism could oxidize ammonia to nitrate, and this was experimentally tested in 2015, which led to the discovery of complete ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (CAOB), and the process was called COMAMMOX (complete ammonia oxidation) [24,25].

To date, all described CAOB are classified within the genus Nitrospira. Their genome encodes both oxidation pathways (ammonia and nitrite), which are concomitantly expressed during growth by ammonia oxidation to nitrate [25]. Physiological studies indicate that CAOB have a high affinity for NH3, which is up to 2500 times lower than that of other AOB, and thus their populations are usually larger in oligotrophic environments [26]. Their affinity for NO2− is also lower than that of other NOB [26]. These microorganisms tend to oxidize NH3 more than NO2− under very low oxygen conditions, which favors their coexistence with other ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms such as anammox bacteria [27,28]. Some comammox strains can utilize O2 or NO3− as terminal electron acceptors and oxidize other substrates, such as H2 and formate [29]. Such metabolic versatility allows them to colonize different natural and artificial ecosystems, such as terrestrial and marine environments, groundwater, freshwater, and wastewater treatment systems [28,30,31].

To date, studies about the diversity and abundance of comammox bacteria in artificial systems have mainly focused on domestic wastewater treatment in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), whereas studies involving leachates are very scarce. For example, Wang et al. (2024) investigated the performance and microbial mechanisms in the treatment of incineration leachate from municipal solid waste employing a combined anaerobic digestion (AD)-anoxic-oxic (A/O) process and found a higher number of sequences of comammox Nitrospira compared to Nitrosomonas, although no specific comammox species were reported [32]. In another study, Wu et al. (2019) reported the cooperation between partial-nitrification, comammox, and anammox during the treatment of sludge digester liquor in a sequencing batch reactor (SBR) [33]. The authors reported that the relative abundance of comammox Nitrospira (0.20%) was higher than that of anammox bacteria (0.10%), and thus Nitrospira was predominant, although the phylogenetic description in this study was only at the genus level [33]. Zhang et al. (2022) investigated the abundance and diversity of comammox microorganisms in the sludges of five WWTPs operated under an anaerobic–anoxic–aerobic process and reported that comammox clade A.1 was widely distributed and mostly comprised Candidatus Nitrospira nitrosa [34]. Zheng et al. (2019) investigated the transcriptional activity, diversity, and phylogeny of CAOB, AOA, and AOB in eight full-scale WWTPs operated under nitrifying conditions and found that the levels of the CAOB amoA gene were higher than those of canonical microorganisms [35]. These authors also found that the relative abundance of the N. nitrosa phylogenetic cluster dominated the CAOB amoA sequences, and a smaller number of sequences corresponded to C. N. nitrificans.

It is noteworthy that, to date, studies on CAOB bacteria in artificial systems have been mainly carried out in domestic wastewater treatment systems, and many of them have identified microorganisms at the genus level. The present study investigated the abundance and diversity of CAOB bacteria during the treatment of leachates from municipal organic waste under nitrifying conditions. There are still very few reports on the presence of these microorganisms in this type of effluent. The main focus of the study was the interaction with other ammonia- and nitrite-oxidizing microorganisms, and results are provided at the species level.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inoculum Source

The inoculum source was obtained from a wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) operated under aerobic conditions located in the city of Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico. The inoculum was washed at least twice with saline solution (0.8% NaCl), the SSV concentration was determined, and it was subsequently stored at 4 °C until use.

2.2. Leachates

Young leachates were obtained directly from trucks used exclusively for the collection of the organic fraction of municipal solid waste (MSW) upon arrival at the composting plant of the city of Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico. The leachates were transported to the laboratory and kept at 4 °C until use. These were characterized by determining the concentrations of ammonium (NH4+), nitrite (NO2−), nitrate (NO3−), COD, and the pH.

2.3. Experimental Conditions

Experiments were conducted in two phases using 1 L reactors with a work volume of 0.8 L. In order to obtain a stable physiological consortium, the reactors were first fed with synthetic medium (mg/L) NH4Cl 385, (NH4)2SO4 470, KH2PO4 560, MgSO4 400, NaCl 400, NaHCO3 3500, and CaCl2 20. Ferrous sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO4·7H2O) was added daily at a concentration of 10 mg/L. The initial NH4+ concentration was 100 mg NH4+-N/L, and 250 mg of NaHCO3-C/L was added to maintain a C/N ratio of 2.5. The reactors were inoculated with a concentration of 2000 ± 150 mg of volatile suspended solids (VSS)/L and operated at 150 rpm, 30 °C, dissolved oxygen (DO) concentrations between 2.1 and 3.2 mg/L, and an initial pH of 7.00 ± 0.15. In the second phase, after the consortium showed stable behavior, the reactors were fed with diluted leachates. Liquid and sludge samples were taken to measure physicochemical parameters and the microbial community structure. Analyses were performed at least in duplicate.

2.4. Analytical Methods

Ammonium was determined using an ion selective electrode (Cole-Parmer model K-27503, Vernon Hills, IL, USA) connected to a multiparameter meter (Mettler Toledo model SevenMulti S47, Schwerzenbach, Switzerland). Nitrite was quantified by the ferrous sulfate method using a high-range nitrite colorimeter checker (HANNA instruments HI708, Eibar, Gipuzkoa, Spain). Nitrate was analyzed by the salicylic acid nitration method using a UV–Visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, UV 1280, Tokyo, Japan) at 410 nm. The pH was determined using an electrode (Thermo Scientific Orion 8102bnuwp ross ultra, Beverly, MA, USA) connected to an Orion Versa Star Advanced Electrochemistry Meter (Thermo Scientific, Beverly, MA, USA). VSS and COD were analyzed following standard methods [36].

2.5. DNA Extraction

Sludge samples were collected from the reactors before and after the addition of leachates. The DNA was extracted from the samples using a commercial kit (Dneasy Power Soil pro kit, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The quality and quantity of the DNA were determined by agarose gel electrophoresis (2%) and with a spectrophotometer (Eppendorf, BioSpectrometer kinetic, Hamburg, Germany).

2.6. Total Genomic DNA Sequencing

Total genomic DNA from sludge samples was analyzed using shotgun metagenomic sequencing methodology according to Novogene Co. Briefly, genomic DNA (1 μg) was randomly fragmented into segments of 350 bp using a Covaris ultrasonic disruptor, which were used to construct the library. The library preparation included end repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, purification, and PCR amplification. The integrity of the library fragments was assessed using an Advanced Analytical Technologies, Inc. (AATI) analysis system. Library quality was analyzed by qPCR and then subjected to PE150 sequencing. The generated sequences were deposited in the NCBI repository (accession number: PRJNA1348307).

2.7. Metagenomic Data Processing and Analysis

Fastp was used for preprocessing the raw data to obtain clean data for subsequent analysis. MEGAHIT was used for the assembly analysis. Contigs from each sample shorter than 500 base pairs (bp) were discarded and effective contigs were used for further analysis. DIAMOND was used for the alignment of unigene sequences using the Micro_NR database, which includes sequences of bacteria, fungi, archaea, and viruses extracted from NCBI’s NR database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 2 march 2024)). MEGAN (MEtaGenome ANalyzer 6.25.10) was used to determine the species annotation of the aligned sequences. The Krona analysis, relative abundance, and bioinformatics analyses were based on the abundance table of each taxonomic hierarchy.

Alpha and beta biodiversity analyses were calculated based on the obtained sequences. The ACE and Chao1 estimators and Shannon and Simpson’s indices were also determined for the bacterial community.

2.8. Analysis of Microbial Behavior

The microbial behavior of the nitrifying sludges was evaluated in terms of substrate consumption efficiency (E, [mg substrate consumed/mg substrate fed] × 100) and production yield (Y, [mg product/mg substrate consumed]). Specific rates of substrate consumption or product generation were calculated using the adjusted Gompertz model and according to Equation (1) [37,38]. In Equation (1), the concentration of NH4+ or COD consumed and NO3− produced (Y [mg/L]) at time t [d] can be expressed as a function of time, where A is the maximum concentration of consumed substrate (NH4+-N or COD [mg/L]) or generated product when time tends to infinity, C is the inflection time [d], B is the volumetric consumption or production rate [mg/L d], and t is time [d]. Regression coefficients were calculated using the statistics 7.0 program.

The maximum volumetric rates (Vmax) of consumption or production, lag time or lag phase (l), and specific rates of consumption or production were calculated according to Martinez-Jardines et al. (2018) [38]. Some parameters were statistically compared between the synthetic medium and leachate assays using t tests (∝ = 0.05). The microbial community results are expressed in terms of relative abundance and are related to the physiological results before and after leachate addition.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physiological Behavior of the Microbial Consortium Subjected to Nitrifying Conditions Fed with Synthetic Medium or Leachates from Municipal Organic Waste

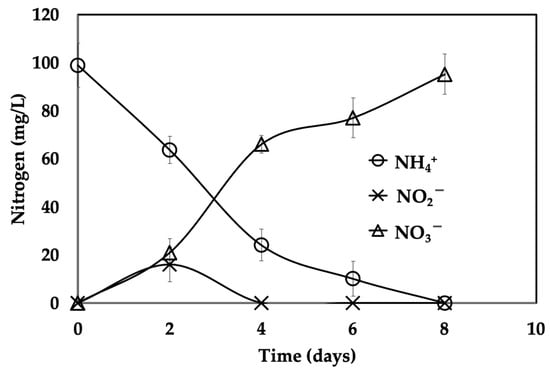

The reactor was fed periodically with synthetic ammonium (100 mg N-NH4+/L) and inorganic carbon (C/N of 2.5) and was considered stable when the mean consumption efficiencies were above 90% and the coefficient of variation was below 10%. Kinetic assays were subsequently performed to evaluate the respiratory process (Figure 1). Ammonium was completely consumed within 8 days. Nitrite generation was transitory, and nitrate generation was concomitant with substrate consumption. Ammonium consumption efficiency (E NH4+-N) was 100% and nitrate production yield (Y NO3−-N) was 0.96 ± 0.01. These results indicate a stable and efficient microbial process.

Figure 1.

Nitrifying profile of a microbial consortium batch-fed with synthetic medium.

The reactor was subsequently fed periodically with leachates diluted with distilled water (1/20). Leachates were diluted because the concentrations of ammonium and COD were higher than 1700 mg NH4+-N/L and 75,000 mg/L, respectively, in the raw leachate, and the main aim was to decrease the initial concentration of COD, since physiological inhibition was observed in the microbial consortium in preliminary assays. Leachate dilution is a suitable strategy for its biological treatment because it prevents osmotic inhibition by reducing the high conductivity caused by high salt concentrations [39]. Conductivity was not measured in the present study, but the COD values obtained were found to be reduced after leachate dilution. High organic matter concentrations can also lead to the inhibition of nitrification because it is a lithoautotrophic process.

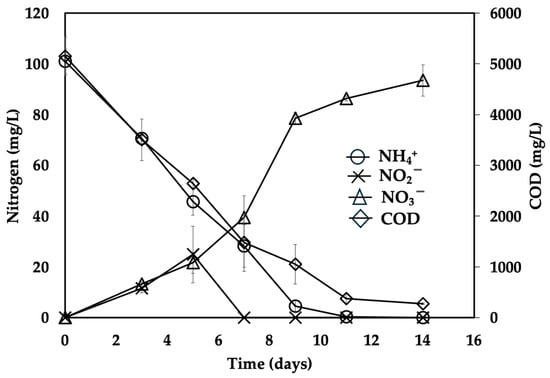

Figure 2 shows the total ammonium consumption at approximately 10 days. Nitrite production was transitory, and nitrate production occurred simultaneously with substrate consumption. Ammonium consumption efficiency was 100% and nitrate production yield was 0.91 ± 0.02. The initial concentration of COD was 5147 ± 374 mg/L and its consumption efficiency was 94.7 ± 1.3%.

Figure 2.

Nitrifying profile of a microbial consortium batch-fed with diluted leachates derived from municipal organic waste.

Table 1 shows the specific rates of ammonium and COD consumption and nitrate production. The values of q NH4+-N obtained with synthetic medium were significantly higher (a = 0.023) than those obtained with leachates (19.29 ± 1.3 mg/g VSS d). The model predictions of the duration of the lag phase of ammonium consumption were less than 0.2 days in both assays, which indicates a very close association with the experimental behavior. The values of q NO3−-N were slightly higher in the assays without leachates, but the difference was not significant. The duration of the lag phase of nitrate production was less than 0.16 days. The q COD was 823 mg/g VSS d, and the duration of the lag phase was very similar to that of ammonium consumption. The values of the determination coefficients of the parameters calculated were higher than 0.97, which indicates an almost perfect fit between the model curve and the experimental data.

Table 1.

Specific rates and lag phase, calculated using a modified Gompertz equation, obtained from nitrifying assays fed with synthetic medium or leachates.

González-Cortés et al. (2022) reported similar specific rates of ammonium consumption (0.98 ± 0.4 mg N-NH4+/g TSS h) when evaluating two different types of landfill leachates from a municipal solid waste treatment plant under nitrifying conditions using a continuous stirred tank bioreactor (CSTBR) of 5 L, although biomass concentration is reported as total suspended solids (TSS) [40]. Torres-Herrera (2025) also reported similar q NH4+-N values after evaluating the treatment of leachates using a pilot-scale SBR nitrification system [39]. These authors mention that q NH4+-N was reduced because of an increase in the pH, which reached values of up to 9.5. They also reported organic matter removal efficiencies of 54 ± 16%. Low removal efficiencies may be attributed to low organic matter biodegradability related to leachate age, where mature leachates show lower biodegradability due to the presence of recalcitrant organic matter. Jiang et al. (2021) also reported low leachate biodegradability when evaluating a combined partial nitrification-Anammox and partial denitrification-Anammox (PnA/PdA) process using a sequencing batch biofilm reactor (SBBR) [41]. These authors attributed this result to the low relation between biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and the total inorganic nitrogen content of the mature leachate evaluated (0.18). In the present study, organic matter (measured as COD) consumption efficiencies reached values of up to 94%. High removal values may be related to the use of young leachates, which exhibit a higher concentration of biodegradable organic matter.

3.2. Analysis of the Microbial Community Subjected to Nitrifying Conditions Fed with Synthetic Medium or Municipal Organic Waste Leachates

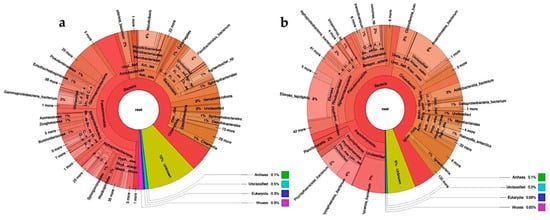

The microbial community was analyzed before (synthetic medium feeding) and during leachate feeding (Figure 3). The performance of the metagenomic sequencing was very similar between the two assays, with total values of approximately 24,586,318 sequences. In the sample without leachates, 88% of the sequences corresponded to the domain Bacteria, 0.1% to Archaea, and the rest to Eukaryota, viruses, unclassified, and unknown (Figure 3a). The domain Bacteria was mainly composed of the phyla Pseudomonadota (44%), Bacteroidota (14%), Actinomycetota (8%), Thermodesulfobacteriota (4%), Acidobacteriota (3%), Verrucomicrobiota (2%), and Planctomycetota (1%). In the sample with leachates, 94% of the sequences corresponded to the domain Bacteria and the rest were similar to the sample without leachates (Figure 3b). In this case, the domain Bacteria also showed a predominance of Pseudomonadota (33%), followed by Planctomycetota (20%), chloroflexota (17%), Actinomycetota (7%), Acidobacteriota (4%), and Myxomicoccota (3%).

Figure 3.

Diversity and abundance of a microbial consortium under nitrifying conditions fed with synthetic medium (a) or diluted leachates from municipal organic waste (b). Abundance corresponds to the total number of sequences quantified in the community (absolute abundance).

A predominance of the phylum Pseudomonadota (formerly known as proteobacteria) has previously been reported in studies evaluating leachate treatment with nitrification. Torres-Herrera et al. (2025) reported a predominance of the phyla Proteobacteria and Bacteroidota in a nitrifying bioreactor fed with landfill leachates [39]. Jian et al. (2021) reported a predominance of the phyla Chloroflexi, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteriota during the treatment of mature landfill leachate using a combined partial nitrification-Anammox and partial denitrification-Anammox (PnA/PdA) single sequencing batch biofilm reactor (SBBR) [41]. González-Cortés et al. (2022) evaluated the acclimatization of a nitrifying biomass fed with two different types of landfill leachates and found that Proteobacteria, Actinobacteriota, and Chloroflexi were the dominant phyla in the biomass without leachates, while leachate feeding favored the presence of Bacteroidetes, Euryarchaeota, and Proteobacteria [40]. Díaz et al. (2019) analyzed the bacterial population in raw leachate and in nitrification–denitrification reactors and reported that Proteobacteria represented more than 50% of the total population [42]. The predominance of Pseudomonadota may be attributed to the high diversity of microbial groups within this phylum and their varied metabolic capabilities. Most microorganisms within this phylum are heterotrophic, but there are also autotrophs and phototrophs. It includes anaerobic, aerobic, and facultative microorganisms. Their metabolic diversity allows these microorganisms to predominate in adverse environments such as the one evaluated in the present study, where a nitrifying consortium was exposed to municipal organic waste leachates. The predominance of these phyla may be related to the high COD removal efficiencies observed in this study.

Table 2 shows the results of species richness and diversity. The number of observed species was 15% higher in the assays with synthetic medium. Similar values were obtained for ACE (abundance-based coverage estimator), which estimates the number of species in the community, and Chao 1, which estimates the total number of species. The Shannon index showed significantly higher values (a = 0.01) with the synthetic medium, indicating greater species richness. Simpson’s index, which estimates species diversity and evenness within a community, also showed higher, albeit not significant, values with the synthetic medium. Jian et al. (2021) reported similar results, where they observed a decrease in the values of ACE, Chao, and Simpson’s index throughout the operation time (day 1 vs. 245) of a reactor during the treatment of mature landfill leachate using a PnA/PdA system [41]. In the present study, a coverage value of 1 was obtained, which indicates high sequencing depth across the entire community. Beta diversity was estimated using a Bray–Curtis dissimilarity-based principal components analysis (Figure S1). The results showed a considerable distance between the two types of feeding evaluated in the reactor. Overall, the data obtained with the ecological estimators and indices indicated that the addition of diluted leachates produced an adverse effect that resulted in a decrease in the total number of species, richness, diversity, and evenness of the microbial community. These data also indicate that not all taxa present at the beginning of the experiment were able to adapt to the presence of leachates.

Table 2.

Ecological estimator and index values obtained from a nitrifying microbial consortium fed with synthetic medium or leachates from municipal organic waste.

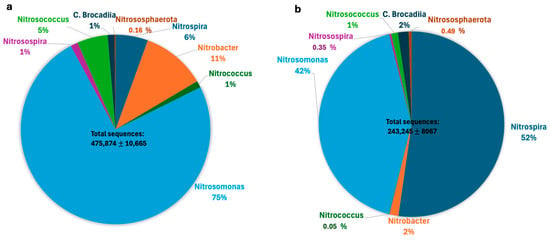

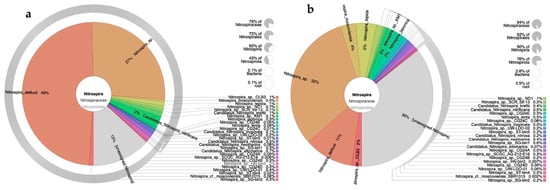

The number of sequences of the ammonium and nitrite oxidizing microbial groups was obtained from the total abundances and defined as ammonium-nitrite oxidizing guild. The sequences of this guild were added together, the proportions of each microbial group were obtained and expressed as a percentage (Figure 4). Therefore, these percentages correspond to relative abundances within the ammonium-nitrite oxidizing guild. The number of detected sequences of microorganisms with these metabolic characteristics during the assay with synthetic medium was 475,585 ± 10,665 (corresponding to 1.93% with respect to the absolute abundance) (Figure 4a). The highest percentage within this guild corresponded to microorganisms belonging to the genus Nitrosomonas, followed by Nitrobacter, Nitrospira, Nitrosococcus, Nitrosospira, and Nitrococcus. Anammox bacteria, classified within the class C. Brocadiia, represented 1%, while ammonia-oxidizing archaea, within the phylum Nitrososphaerota, represented 0.16%. The microbial consortium fed with diluted leachates showed a total number of 243,245 ± 8067 sequences (corresponding to 0.98% with respect to the absolute abundance) (Figure 4b). This value corresponded to a decrease of 50% compared to that observed with the synthetic medium, indicating a negative effect of the addition of organic waste. The highest percentage of sequences within this guild corresponded to the genus Nitrospira, followed by Nitrosomonas, Nitrobacter, class C. Brocadiia, Nitrosococcus, phylum Nitrososphaerota, Nitrosospira, and Nitrococcus.

Figure 4.

Relative percentage of microbial group sequences within the oxidizing ammonium-nitrite guild obtained from the total abundance of a consortium under nitrifying conditions fed with synthetic medium (475,874 ± 10,665 total sequences) (a) or diluted leachates (243,245 ± 8067 total sequences) (b) from municipal organic waste.

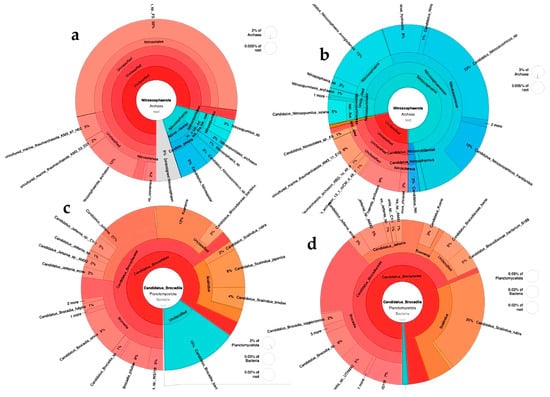

Figure 5 shows the diversity and percentages (obtained from absolute abundance) of ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms belonging to the domain Archaea and the anammox group. In the assay with synthetic medium, the Archaea sequences with the highest percentage corresponded to Candidatus nitrosotalea, followed by Nitrosophaerota archaeon, Candidatus Nitrosopolaris wilkensis, Candidatus Nitrosocosmicus sp., and Nitrosopumilus sp. (Figure 5a). In the assay with leachates, the predominant sequences corresponded to Candidatus Nitrosocosmicus sp., followed by microorganisms of the genera Nitrososphaera, Nitrosopumilus, and Nitrosotalea (Figure 5b). In the case of anammox bacteria, the sequences that predominated in the assays with synthetic medium corresponded to the genus Candidatus Brocadia, such as C. Brocadia sinica, followed by C. Jettenia ecosi, C. Scalindua japonica, and C. Kuenenia (Figure 5c). In the reactors fed with leachates, the same four genera were observed, with a predominance of C. Brocadia, followed by C. Scalindua (Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Diversity and abundance of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and anammox microorganisms in a microbial consortium under nitrifying conditions fed with synthetic medium or diluted leachates from municipal organic waste. Archaea: (a) synthetic medium, (b) diluted leachates; anammox: (c) synthetic medium, (d) diluted leachates. Abundance corresponds to the total number of sequences quantified in the community (absolute abundance).

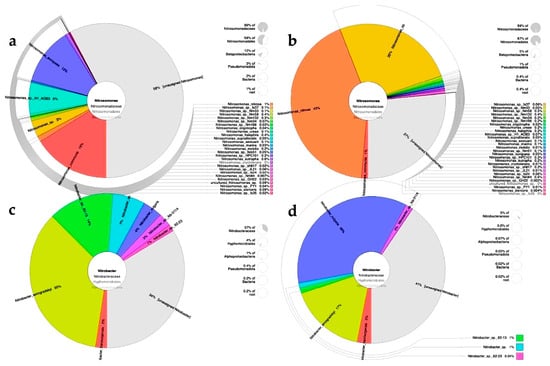

Figure 6 shows the diversity and percentages (obtained from absolute abundance) of microorganisms of the genera Nitrosomonas and Nitrobacter. Regarding the Nitrosomonas genus, the predominant sequences corresponded to the species N. communis, followed by N. europaea, N. sp., and N. nitrosa (Figure 6a). When fed with leachates, the predominant species were N. Nitrosa and N. sp., while there was a pronounced decrease in the abundance of N. communis (Figure 6b). Regarding the Nitrobacter genus, the most representative species, regardless of the feeding source, in descending order were N. winogradskyi, N. sp., N. vulgaris, and N. hamburgensis. With respect to Nitrosococcus, the most predominant species in descending order were N. halophilus, N. wardiae, N. oceani, and N. watsonii (Figure S2). Regarding the Nitrosospira genus, the species detected were N. sp., N. lacus, N. multiformes, and N. briensis (Figure S2). With respect to Nitrococcus genus, N. mobilis was the only species detected.

Figure 6.

Diversity and abundance of microorganisms of the genera Nitrosomonas and Nitrobacter in a microbial consortium under nitrifying conditions fed with synthetic medium or diluted leachates from municipal organic waste. Nitrosomonas: (a) synthetic medium, (b) diluted leachates; Nitrobacter: (c) synthetic medium, (d) diluted leachates. Abundance corresponds to the total number of sequences quantified in the community (absolute abundance).

In the present study, the decrease observed in the number of sequences of ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms was similar to that reported by González-Cortés et al. (2022) during the acclimatization of a nitrifying biomass to two different landfill leachates (12 and 19 operation years) obtained from a municipal solid waste treatment plant [40]. These authors found that feeding with landfill leachate affected the AOB population, reducing its relative abundance from 10.5% to 1.0%, and the relative abundances of Nitrosomonas and Nitrosospira were lower than 0.02%. This decrease may be attributed to the sensitivity of AOB to the presence of different toxic organic compounds, changes in pH, and high salinity [43]. In the present study, the initial COD concentration in the assays with diluted leachates was 5147 ± 374 mg/L, which could have had a negative effect on the abundance of these bacteria. Díaz et al. (2019) used personal genome machine (PGM) sequencing to evaluate the bacterial communities in a nitrification–denitrification process fed with urban landfill leachates [42]. The authors reported the presence of Nitrosomonas, Nitrosospira, and Nitrosococcus, although data on their relative abundance were not provided. Fitzgerald et al. (2015) analyzed the ammonia-oxidizing microbial communities in nitrifying chemostat reactors inoculated with sludge from a WWTP and fed with synthetic medium (30 mg NH4+-N/L) under low dissolved oxygen (DO < 0.3 mg/L) conditions at a temperature between 21 and 23 °C [44]. The authors reported that 1% of the obtained DNA sequences of AOB corresponded to species of the genus Nitrosomonas, such as N. oligotropha, N. eutropha, and N. europaea, and to the genus Nitrosococcus sp. They also obtained sequences of AOA, which corresponded to Nitrosopumilus maritimus and Ca. Nitrosoarchaeum koreensis MY1. These authors also reported sequences of NOB (2.3%) related to Nitrospira defluvii but did not obtain sequences of anammox microorganisms. Xie et al. (2013) evaluated an aged refuse bioreactor in the removal of nitrogen in a mature landfill leachate [45]. The bioreactor consisted of a PVC column (30 cm inner diameter, 100 cm height) fed with total nitrogen (TN) between 0.73 and 2.03 g TN/kg VS d, with DO concentrations between 0.2–0.5 mg/L and a temperature of 30 °C, resulting in TN removal efficiencies of 96%. The analysis of the microbial community in this study showed a predominance of the AOB genera Nitrosomonas, Nitrosospira, and Nitrosococcus, with percentages between 0.49 and 1.78%. The predominating NOB genera were Nitrospira (0.13%) and Nitrobacter (0.05). Anammox bacteria accounted for 0.27%, where the main species detected was Kuenenia stuttgartiensis.

In the present study, the abundance of each of these ammonia-oxidizing microbial groups did not reach percentages above 1% with respect to the total. A low presence of these microorganisms is considered typical in the treatment of leachates with nitrification [39,40,41]. Torres-Herrera et al. (2025) reported relative abundances of the genus Nitrosomonas between 0.1 and 0.4%, while those of Nitrobacter ranged between 0.2 and 1.4% [39]. Jiang et al. (2021) evaluated nitritation and denitritation with anammox in an SBR for the treatment of mature leachates using floc sludge and biofilm [41]. The results showed that the relative abundance of Nitrosomonas decreased from 2.75 to 0.78% in the floc sludge and from 1.51 and 0.34% in the biofilm, which was attributed to the duration of the experiment and the increase in organic matter concentration. In the same study, the relative abundance of Nitrospira increased from 0.01 to 0.08% in the floc sludge and decreased from 0.18 to 0.09% in the biofilm, which was attributed to the diffusion of dissolved oxygen. Regarding anammox microorganisms, these authors reported that the family Brocadiaceae showed a greater decrease in the floc sludge (0.25 to 0.02%) than in the biofilm (1.06 to 0.98%), indicating a preference for the latter. The genera Kuenenia and Jettenia showed an increase in the floc sludge (0.02 to 1.14%) and the biofilm (0.08 to 0.98%) over time, which was attributed to their capacity to persist in leachate treatment systems with high ammonium concentrations [46].

Figure 7 shows the diversity and abundance (obtained from absolute abundance) of bacteria of the genus Nitrospira, which includes comammox microorganisms. This genus was the only one that showed an increase in the percentage of its sequences when the reactor was fed with diluted leachates (Figure 4). When the reactor was fed with synthetic medium, the predominant canonical species was Nitrospira defluvii (49%, 12,799 sequences), followed by N. sp., Nitrospira unassigned, and Candidatus N. nitrificants. When the reactor was fed with leachates, species abundances were as follows: 11% N. defluvii (14,290 sequences), 32% N. sp., 5% N. tepida, 4% N. moscoviensis, 2% N. japonica, and 36% corresponded to Nitrospira unassigned.

Figure 7.

Diversity and abundance of the genus Nitrospira, including comammox bacteria, in a microbial consortium under nitrifying conditions fed with synthetic medium (a) or diluted leachates from municipal organic waste (b). Abundance corresponds to the total number of sequences quantified in the community (absolute abundance).

In the case of comammox microorganisms, the predominant species observed in the assays with synthetic medium were Candidatus Nitrospira nitrificants, C. N. kreftii, C. N. allomarina, C. N. nitrosa, C. N. inopinata, and C. N. neomarina. When fed with leachates, the same species were still observed but in the following descending order: C. N. inopinata, C. N. nitrificants, C. N. kreftii, C. N. neomarina, C. N. nitrosa, and C. N. allomarina. The total number of sequences of comammox microorganisms in the synthetic medium was 1321, which was essentially doubled in the presence of leachates, where 2585 sequences were observed. The number of sequences of C. N. nitrificants was similar with both types of feeding, while the rest of the species increased at least twofold in the presence of leachates, except for C. N. allomarina, which decreased by 50%. These results indicated that comammox microorganisms were able to adapt and increase in number when exposed to organic waste leachates. Despite their relatively low number of sequences in the presence of leachates, these microorganisms showed higher values compared to other canonical genera such as Nitrococcus (141) and Nitrosospira (871) and were somewhat similar to Nitrosococcus (2851). The total number of sequences of the genera Nitrobacter and Nitrosomonas was 0.5 and 40 times higher, respectively, than those of comammox microorganisms. However, comammox sequences doubled the number of those obtained for ammonia-oxidizing archaea (Nitrososphaerota) but were 50% less than those detected for anammox microorganisms (C. Brocadiia). These results indicate that comammox microorganisms co-participate in leachate treatment at levels similar to or exceeding those of canonical groups. These results could also indicate the ability of comammox microorganisms to co-participate in systems for the treatment of polluting effluents with high concentrations of ammoniacal nitrogen and organic matter.

Research on comammox bacteria in landfill leachate treatment remains extremely limited. However, there are studies evaluating these microorganisms in nitrogen removal in other types of wastewaters. For example, Wang et al. (2024) investigated the treatment of incineration leachate from municipal solid waste employing a combined anaerobic digestion (AD)-anoxic-oxic (A/O) process [32]. The authors found that comammox Nitrospira was dominant over Nitrosomonas for nitrification due to the low NH4+-N concentration in the A/O tanks (<35 mg/L); however, comammox microorganisms were not reported at the species level. Wu et al. (2019) reported the cooperation between partial-nitrification, comammox, and anammox during sludge digester liquor treatment in an SBR [33]. The authors found that ammonium concentrations of 2200 mg/L of NH4+-N were removed by 98.82%. Furthermore, the relative abundance of the dominant ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (Chitinophagaceae) was 18.89%, and the abundance of anammox (Candidatus Kuenenia) and comammox (Nitrospira) bacteria was 0.10% and 0.20%, respectively, which indicates that comammox bacteria play an important role in nitrogen removal. However, this study does not provide the species of comammox microorganisms because the phylogenetic description was limited to the genus level. Koike et al. (2022) evaluated a full-scale bioreactor (13.5 m3) in the treatment of ammonium in groundwater (9.3 mg NH4+-N/L) and investigated the ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms present [30]. The authors reported that ammonium was oxidized and the microbial community showed a high abundance of Nitrospira (12.5–45.9%), where the dominant sequence was most closely related to Candidatus Nitrospira nitrosa (3.5–37.8%). Zhang et al. (2022) investigated the relative abundance and diversity of comammox microorganisms in sludges of five WWTPs that used an anaerobic–anoxic–aerobic process and reported that comammox clade A.1 was widely distributed and mostly comprised Candidatus Nitrospira nitrosa (>98% of all comammox) [34]. Zheng et al. (2019) investigated the transcriptional activity, diversity, and phylogeny of CAOB, AOA, and AOB in eight full-scale WWTPs operated under nitrifying conditions containing between 14 and 29 mg NH4+-N/L and 37 and 450 mg COD/L [35]. The results indicated that the transcriptional levels of the CAOB amoA gene were higher than those of canonical microorganisms. The results also showed that the relative abundance of N. nitrosa was dominant (97% of the total), and a smaller number of sequences corresponded to C. N. nitrificans, while C. N. inopinata was not detected.

In the present study, the highest number of sequences of comammox microorganisms in the presence of leachates corresponded to a C. N. Inopinata. This result may be attributed to the physiological characteristics described for this species, particularly its high affinity for ammonium, which is usually higher than that of many other ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms under oligotrophic conditions [47]. Kinetic studies have revealed that this species is able to compete at extremely low ammonia concentrations (Ks ≈ 60 nM) but has a low affinity for nitrite (Ks ≈ 500 μM), which indicates better metabolic performance in ammonia oxidation than in nitrite oxidation in oligotrophic environments where nitrite concentrations are typically low [26]. Other studies have also found that C. N. inopinata is able to biotransform a wide range of micropollutants using ammonia rather than nitrite as an energy source and is also able to biotransform various antibiotics [48,49]. This metabolic ability could have contributed to its increased presence in the assays fed with leachates from municipal organic waste, which have a complex chemical composition.

In general, based on the physiological and microbial community results, the following could be established. The addition of leachate had a negative effect on the total microbial community of the nitrifying reactor, decreasing species richness and diversity. Consequently, the metabolism and nitrifying community were also affected, decreasing the rates of ammonium consumption and nitrate production, although total ammonium consumption was achieved. Almost total COD consumption was also observed, attributed to the high abundance of heterotrophic microorganisms coexisting in the nitrifying reactor. These conditions may have favored an oligotrophic environment. The total abundance of ammonium- and nitrite-oxidizing microbial genera decreased dramatically, with the exception of Nitrospira, which increased from 0.1 to 0.5%, indicating greater tolerance to organic matter. Within the ammonium-nitrite-oxidizing guild, the relative abundance of the genus Nitrospira was also the only one to increase, from 5.5 to 52%. In turn, within the Nitrospira genus, comammox microorganisms doubled their number of sequences, with C. N. inopinata being predominant. This group of microorganisms, together with anammox bacteria and the archaeal domain, was the only ones that did not decrease in the presence of leachates. The co-occurrence of comammox microorganisms and anammox bacteria has been previously reported, indicating a cooperative effect [50]. Vilardi et al. (2023) evaluated ammonium removal (28 mg N-NH4+/L) of wastewater in full-scale reactors under dissolved oxygen concentrations of up to 6 mg/L [50]. The authors found predominant relative abundances of C. Brocadia and C. N. nitrosa compared to other ammonium-nitrite oxidizing microbial groups, concluding that there is cooperation between comammox and anammox bacteria, where the former improve the environment by providing nitrite and consuming oxygen, while the latter maintain nitrite at concentrations that are not inhibitory to comammox bacteria. In this work, a similar mechanism can be proposed, considering the operational conditions evaluated, such as oxygen concentrations around 3 mg/L and the aforementioned results on the total abundances of the ammonium and nitrite oxidizing groups. In this case, reporting the predominance of C. N. inopinata, which is attributed to its high affinity for ammonium and its ability to biotransform organic compounds. Another factor that may have contributed to the greater abundance of comammox microorganisms is the longer than 10 days of batch culture. It has been reported that solid retention times greater than 10 days in bioreactors favor the growth of slow-growing nitrifying microorganisms in oligotrophic environments [51,52,53]. In these environments, microorganisms of the genus Nitrospira have been considered to employ a k-strategy for their growth and reproduction [54]. This behavior has been observed in recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS), where comammox Nitrospira, along with ammonia-oxidizing archaea, have also been found to predominate over other groups of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria [55]. Bartelme et al. (2017) reported the predominance of ammonia-oxidizing archaea in RAS environments, indicating that the nucleotide sequences were affiliated with members of the genera Nitrososphaera and Candidatus Nitrosocosmicus [55]. In this regard, it has been indicated that ammonia-oxidizing archaea outcompete ammonia-oxidizing bacteria at low ammonia concentrations [56]. The interaction of comammox microorganisms and their predominance over other oxidizing ammonium-nitrite groups in environments contaminated by organic waste leachate is a matter that deserves further investigation.

4. Conclusions

The present study addressed the treatment of diluted leachates from municipal organic waste using nitrification with the main objective of evaluating the diversity and abundance of comammox bacteria and their interaction with other canonical microorganisms. The physicochemical characterization of the leachates showed ammoniacal nitrogen concentrations of up to 1700 mg/L and COD concentrations of 75,000 mg/L, and thus the leachates were diluted for the experiment. Batch reactors (1 L) were fed with either synthetic ammonium (100 mg HN4+-N/L) or leachates, which showed concentrations of 5200 mg COD/L after being diluted. Ammonium and COD consumption efficiencies were 100% and 95%, respectively. Specific rates of ammonium consumption decreased significantly in the presence of leachates. Nitrate production rates also decreased, but not significantly.

The microbial community analysis, which included ecological estimators and indices, showed a decrease in diversity and richness (15%) in the presence of leachates. When fed with synthetic medium, the highest percentage of detected sequences of the ammonia-and nitrite-oxidizing guild corresponded to the genus Nitrosomonas (75%), followed by Nitrobacter (11%), Nitrospira (6%), Nitrosococcus (5%), Nitrosospira (1%), and Nitrococcus (1%), and the rest corresponded to anammox and archaea sequences. When fed with leachates, the predominant sequences corresponded to Nitrospira (52%), Nitrosomonas (42%), Nitrobacter (2%), anammox (2%), and Nitrosococcus (1%), and the rest corresponded to Nitrosospira, Nitrococcus, and Archaea. The total number of sequences of comammox microorganisms was higher compared to those of other canonical genera such as Nitrococcus and Nitrosospira and was similar to that of Nitrosococcus. The number of sequences of Nitrobacter and Nitrosomonas was 0.5 and 40 times higher, respectively, than that of comammox sequences. Comammox sequences were twice as abundant as those of Archaea and half as abundant as those of anammox. The sequences of comammox microorganisms in synthetic medium or leachates corresponded to Candidatus Nitrospira inopinata, C. N. nitrificants, C. N. kreftii, C. N. neomarina, C. N. nitrosa, and C. N. allomarina. The sequences of C. N. inopinata were predominant in the presence of leachates, indicating its capacity to persist in environments with a complex chemical composition, as has been demonstrated by previous studies. These findings confirm that comammox and canonical microorganisms coexist during ammonium removal from leachates derived from municipal organic waste, thereby expanding the range of environments these microorganisms can colonize.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/environments12120479/s1, Figure S1: Beta diversity analysis of a nitrifying community fed with synthetic ammonium or leachates; Figure S2: Diversity and abundance of microorganisms of the genera Nitrosococcus and Nitrosospira in a microbial consortium under nitrifying conditions fed with synthetic medium or diluted leachates from municipal organic waste. Nitrosococcus: (a) synthetic medium, (b) diluted leachates; Nitrosospira: (c) synthetic medium, (d) diluted leachates.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.-H.; methodology, R.C.M.-Q., Á.I.O.-C. and S.M.-H.; formal analysis, S.M.-H.; investigation, R.C.M.-Q., Á.I.O.-C. and S.M.-H.; resources, S.M.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C.M.-Q. and S.M.-H.; writing—review and editing, R.C.M.-Q., Á.I.O.-C. and S.M.-H.; supervision, S.M.-H.; project administration, S.M.-H.; funding acquisition, S.M.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CONAHCYT (now SECIHTI), grant number CF-2023-I-345.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Roberto Carlos Moreno Quirós acknowledges the Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI), Mexico, for the doctoral scholarship (CVU: 1035411). The authors thank the Municipality of Xalapa, the staff of the Department of Environment and the Composting Center for the permission and support granted.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DO | Dissolved oxygen |

| COD | Chemical oxygen demand |

| BT | Billion tons |

| MSW | Municipal solid waste |

| AOB | Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria |

| NOB | Nitrite-oxidizing bacteria |

| ANAMMOX | Anaerobic ammonium oxidation |

| CAOB | Complete ammonia-oxidizing bacteria |

| AOA | Ammonia-oxidizing archaea |

| COMAMMOX | Complete ammonia oxidation |

| WWTPs | Wastewater treatment plants |

| AD | Anaerobic digestion |

| AO | Anoxic-oxic |

| SBR | Sequencing batch reactor |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleid acid |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| AATI | Advanced analytical technologies Inc |

| PE | Paired end |

| NCBI | National center for biotechnology information |

| BP | Base pairs |

| ACE | Abundance-based coverage estimator |

| TSS | Total suspended solids |

| VSS | Volatile suspended solids |

| CSTBR | Continuous stirred tank bioreactor |

| SBBR | Sequencing batch biofilm reactor |

| PNA/PDA | Partial nitrification-anammox/partial denitrification-anammox |

| BOD | Biochemical oxygen demand |

| PGM | Personal genome machine |

| PVC | Polyvinyl chloride |

| TN | Total nitrogen |

| VS | Volatile solids |

References

- United Nations Environmental Program. Global Waste Management Outlook 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.unep.org/ietc/resources/report/global-waste-management-outlook-2024 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Siddiqua, A.; Hahladakis, J.N.; Al-Attiya, W.A.K.A. An overview of the environmental pollution and health effects associated with waste landfilling and open dumping. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 58514–58536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, E.C.; Ragazzi, M.; Torretta, V. Management of municipal solid waste in developing countries: Current status and future perspectives. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijekoon, P.; Koliyabandara, P.A.; Cooray, A.T.; Lam, S.S.; Bandunee, C.L.; Athapattu, B.C.L.; Vithanage, M. Progress and prospects in mitigation of landfill leachate pollution: Risk, pollution potential, treatment and challenges. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 421, 126627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, T.A.; Lo, W.H.; Chan, G.Y. Physico–chemical treatments for removal of recalcitrant contaminants from landfill leachate. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 129, 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, J.L.; Zamora, P.P. Use of advanced oxidation processes to improve the biodegradability of mature landfill leachates. J. Hazard. Mater. 2005, 123, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Quirós, R.C.; Guzmán-López, O.; Leal-Ascencio, M.T.; Ortiz-Ceballos, A.I.; Castro-Luna, A.A.; Martínez-Hernández, S. Characterization of organic waste from the municipal composting center of Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico. Ecosistemas Y Recur. Agropecu. 2025, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gong, B.; Lin, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, J. Robustness and microbial consortia succession of simultaneous partial nitrification, ANAMMOX and denitrification (SNAD) process for mature landfill leachate treatment under low temperature. Biochem. Eng. J. 2018, 132, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, H.; Ma, Y.; An, F.; Huang, J.; Shao, Z. Achieving stable two-stage mainstream partial-nitrification/anammox (PN/A) operation via intermittent aeration. Chemosphere 2020, 245, 125650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Wang, L.; Cheng, L.; Yang, W.; Gao, D. Nitrogen Removal from Mature Landfill Leachate via Anammox Based Processes: A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Jardines, M.A.; Cuervo-López, F.M.; Martínez-Hernández, S. Physiological and Microbial Community Analysis During Municipal Organic Waste Leachate Treatment by a Sequential Nitrification-Denitrification Process. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 2024, 235, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyikoglu, R.; Karatas, O.; Rezania, H.; Kobya, M.; Vatanpour, V.; Khataee, A. A review on treatment of membrane concentrates generated from landfill leachate treatment processes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 259, 118182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tang, F.; Xu, D.; Xie, B. Advances in Biological Nitrogen Removal of Landfill Leachate. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamrah, A.; AL-Zghoul, T.M.; Al-Qodah, Z. An Extensive Analysis of Combined Processes for Landfill Leachate Treatment. Water 2024, 16, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Shafy, H.I.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Al-Sulaiman, A.M.; Okasha, R.A. Landfill leachate: Sources, nature, organic composition, and treatment: An environmental overview. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, H.A.; Ramli, S.F.; Hung, Y.T. Physicochemical Technique in Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) Landfill Leachate Remediation: A Review. Water 2023, 15, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qiao, Z. A comprehensive review of landfill leachate treatment technologies. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1439128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaoui, Y.; Bouzid, J.; Sayadi, S. Combination of air stripping and biological processes for landfill leachate treatment. Environ. Eng. Res. 2020, 25, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, D.; Soto, J.; Villamizar, S.; Machuca-Martínez, F.; Ramírez, L. Alternative for the Treatment of Leachates Generated in a Landfill of Norte de Santander–Colombia, by Means of the Coupling of a Photocatalytic and Biological Aerobic Process. Top. Catal. 2020, 63, 1336–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Sundaram, B. Efficacy of nanoparticles as photocatalyst in leachate treatment. Nanotechnol. Environ. Eng. 2022, 7, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winogradsky, S. Recherches sur les organismes de la nitrification. Ann. Inst. Pasteur. 1890, 4, 213–231. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, A.; Van de Graaf, A.; Robertson, L.A.; Kuenen, J.G. Anaerobic ammonium oxidation discovered in a denitrifying fluidized bed reactor. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1995, 16, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Könneke, M.; Bernhard, A.; de la Torre, J.; Walker, C.B.; Waterbury, J.B.; Stahl, D.A. Isolation of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing marine archaeon. Nature 2005, 437, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, E.; Perez, J.; Kreft, J.U. Why is metabolic labour divided in nitrification? Trends Microbiol. 2006, 14, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daims, H.; Lebedeva, E.V.; Pjevac, P.; Han, P.; Herbold, C.; Albertsen, M.; Jehmlich, N.; Palatinszky, M.; Vierheilig, J.; Bulaev, A. Complete nitrification by Nitrospira bacteria. Nature 2015, 528, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kits, K.D.; Sedlacek, C.J.; Lebedeva, E.V.; Han, P.; Bulaev, A.; Pjevac, P.; Daebeler, A.; Romano, S.; Albertsen, M.; Stein, L.Y.; et al. Kinetic analysis of a complete nitrifier reveals an oligotrophic lifestyle. Nature 2017, 549, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Kessel, M.A.H.J.; Speth, D.R.; Albertsen, M.; Nielsen, P.H.; Op den Camp, H.J.; Kartal, B.; Jetten, M.S.M.; Lücker, S. Complete nitrification by a single microorganism. Nature 2015, 528, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddela, N.R.; Gan, Z.; Meng, Y.; Fan, F.; Meng, F. Occurrence and Roles of Comammox Bacteria in Water and Wastewater Treatment Systems: A Critical Review. Engineering 2022, 17, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daims, H.; Wagner, M. Nitrospira. Trends Microbiol. 2018, 26, 462–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, K.; Smith, G.J.; Yamamoto-Ikemoto, R.; Lücker, S.; Matsuura, N. Distinct comammox Nitrospira catalyze ammonia oxidation in a full-scale groundwater treatment bioreactor under copper limited conditions. Water Res. 2022, 210, 117986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, M.; Zheng, M.; Liu, H.; Kuang, S.; Chen, H.; Li, X. Abundance, diversity, and community structure of comammox clade A in sediments of China’s offshore continental shelf. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 889, 164290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ma, X.; Ran, X.; Wang, T.; Zhou, M.; Liu, C.; Li, X.; Wu, M.; Wang, Y. Analyzing performance and microbial mechanisms in an incineration leachate treatment after waste separation: Integrated metagenomic and metaproteomic analyses. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Shen, M.; Li, J.; Huang, S.; Li, Z.; Yan, Z.; Peng, Y. Cooperation between partial-nitrification, complete ammonia oxidation (comammox), and anaerobic ammonia oxidation (anammox) in sludge digestion liquid for nitrogen removal. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254 Pt A, 112965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.N.; Wang, J.G.; Wang, D.Q.; Jiang, Q.Y.; Quan, Z.X. Abundance and Niche Differentiation of Comammox in the Sludges of Wastewater Treatment Plants That Use the Anaerobic–Anoxic–Aerobic Process. Life 2022, 12, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Wang, M.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, N.; He, S.; Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. Transcriptional activity and diversity of comammox bacteria as a previously overlooked ammonia oxidizing prokaryote in full-scale wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 656, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 21st ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zwietering, M.H.; Jongenburger, I.; Rombouts, F.M.; Van’t Riet, K. Modeling of the bacterial growth curve. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1990, 56, 1875–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Jardines, M.; Martínez-Hernández, S.; Texier, A.C.; Cuervo-López, F. 2-Chlorophenol consumption by cometabolism in nitrifying SBR reactors. Chemosphere 2018, 212, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Herrera, S.; Palomares-Cortés, J.; González-Cortés, J.J.; Cubides-Páez, D.F.; Gamisans, X.; Cantero, D.; Ramírez, M. Start-up and long-term operation of the nitrification process using landfill leachates in a pilot sequencing batch bioreactor. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 70, 106895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cortés, J.J.; Valle, A.; Ramírez, M.; Cantero, D. Characterization of Bacterial and Archaeal Communities by DGGE and Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) of Nitrification Bioreactors Using Two Different Intermediate Landfill Leachates as Ammonium Substrate. Waste Biomass Valor. 2022, 13, 3753–3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Yang, P.; Wang, Z.; Ren, S.; Qiu, J.; Liang, H.; Peng, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q. Efficient and advanced nitrogen removal from mature landfill leachate via combining nitritation and denitritation with Anammox in a single sequencing batch biofilm reactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 333, 125138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, A.I.; Oulego, P.; Laca, A.; González, J.M.; Díaz, M. Metagenomic analysis of bacterial communities from a nitrification-denitrification treatment of landfill leachates. Clean 2019, 47, 1900156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liang, X.; Han, Y.; Cai, Y.; Zhao, H.; Sheng, M.; Cao, G. The coupling use of advanced oxidation processes and sequencing batch reactor to reduce nitrification inhibition of industry wastewater: Characterization and optimization. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 360, 1577–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, C.M.; Camejo, P.; Oshlag, J.Z.; Noguera, D.R. Ammonia-oxidizing microbial communities in reactors with efficient nitrication at low-dissolved oxygen. Water Res. 2015, 70, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, B.; Lv, Z.; Hu, C.; Yang, X.; Li, X. Nitrogen removal through different pathways in an aged refuse bioreactor treating mature landfill leachate. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 9225–9234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, H.; Ren, S.; Wang, W.; Peng, Y. Enhanced nitrogen removal from nitrate-rich mature leachate via partial denitrification (PD)-anammox under real-time control. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 289, 121615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, K.M.; Caranto, J.D.; Majer, S.H.; Smith, M.A. Alternative bioenergy: Updates to and challenges in nitrification metalloenzymology. Joule 2018, 2, 421–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Tian, Z.; Li, Z.; Hou, L.; Liu, M.; Wu, Q.; Wagner, M.; Men, Y. Specific micropollutant biotransformation pattern by the comammox bacterium Nitrospira inopinata. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 8695–8705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.J.; Han, P.; Zhao, M.; Yu, Y.; Sun, D.; Hou, L.; Liu, M.; Zhao, Q.; Tang, X.; Klümper, U.; et al. Biotransformation of lincomycin and fluoroquinolone antibiotics by the ammonia oxidizers AOA, AOB and comammox: A comparison of removal, pathways, and mechanisms. Water Res. 2021, 196, 117003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilardi, K.; Cotto, I.; Bachmann, M.; Parsons, M.; Klaus, S.; Wilson, C.; Bott, C.B.; Pieper, K.J.; Pinto, A.J. Co-Occurrence and Cooperation between Comammox and Anammox Bacteria in a Full-Scale Attached Growth Municipal Wastewater Treatment Process. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 5013–5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How, S.W.; Nittami, T.; Ngoh, G.C.; Curtis, T.P.; Chua, A.S.M. An efficient oxic-anoxic process for treating low COD/N tropical wastewater: Startup, optimization and nitrifying community structure. Chemosphere 2020, 259, 127444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotto, I.; Dai, Z.; Huo, L.; Anderson, C.L.; Vilardi, K.J.; Ijaz, U.; Khunjar, W.; Wilson, C.; De Clippeleir, H.; Gilmore, K.; et al. Long solids retention times and attached growth phase favor prevalence of comammox bacteria in nitrogen removal systems. Water Res. 2020, 169, 115268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrani, M.J.; Sobotka, D.; Kowal, P.; Ciesielski, S.; Makinia, J. The occurrence and role of Nitrospira in nitrogen removal systems. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 303, 122936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowka, B.; Daims, H.; Spieck, E. Comparative oxidation kinetics of nitrite-oxidizing bacteria: Nitrite availability as key factor for niche differentiation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartelme, R.P.; McLellan, S.L.; Newton, R.J. Freshwater Recirculating Aquaculture System Operations Drive Biofilter Bacterial Community Shifts around a Stable Nitrifying Consortium of Ammonia-Oxidizing Archaea and Comammox Nitrospira. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzenpichler, R. Diversity, physiology, and niche differentiation of ammonia-oxidizing archaea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 7501–7510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).