Discovering Organisational Leadership Archetypes in Peru’s Circular Water Economy Using Latent Class Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

Literature Review

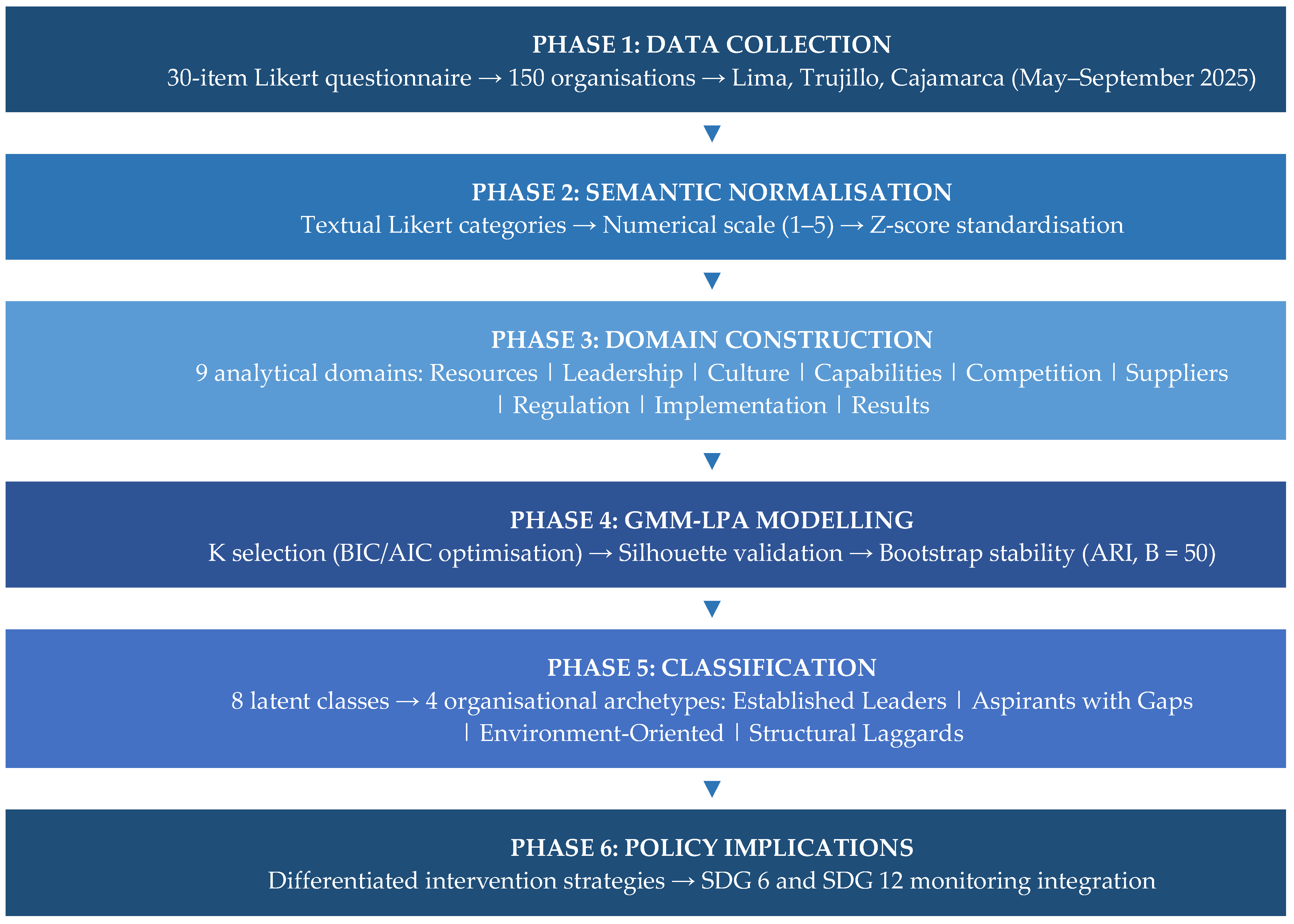

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Approach

2.2. Sample and Data Collection

2.3. Measurement Instrument

2.4. Theoretical Rationale for Analytical Domains

2.5. Methodological Processing

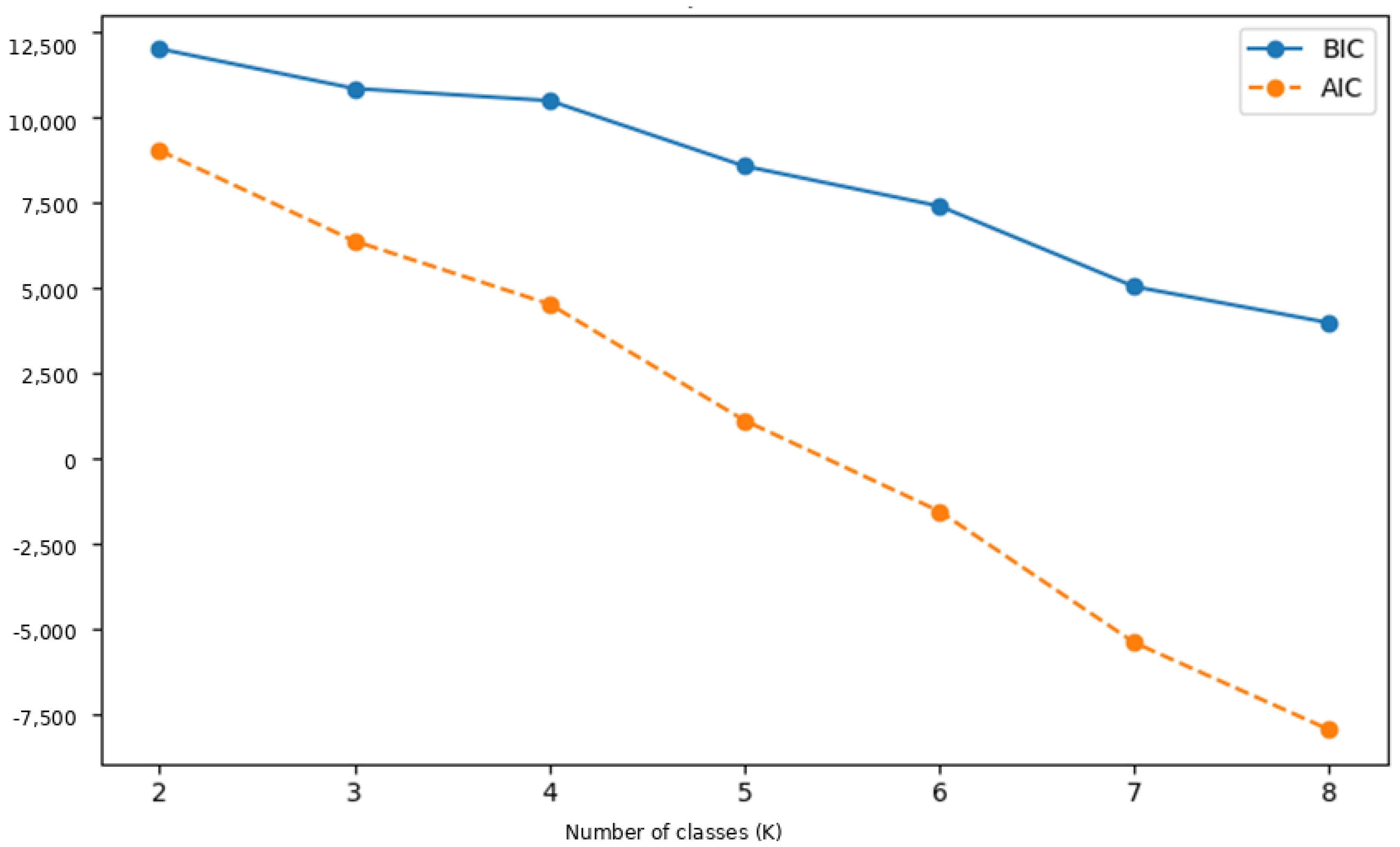

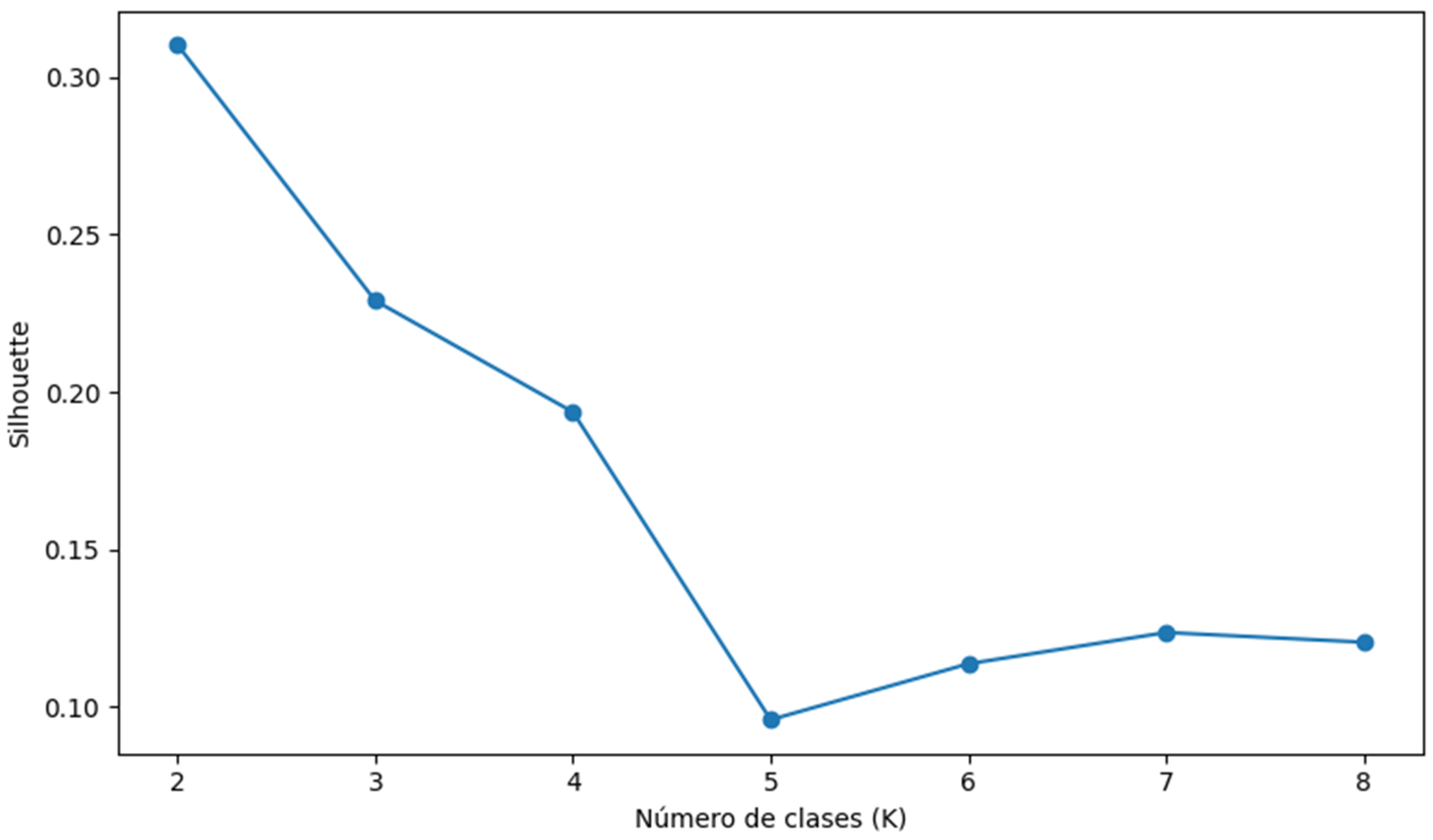

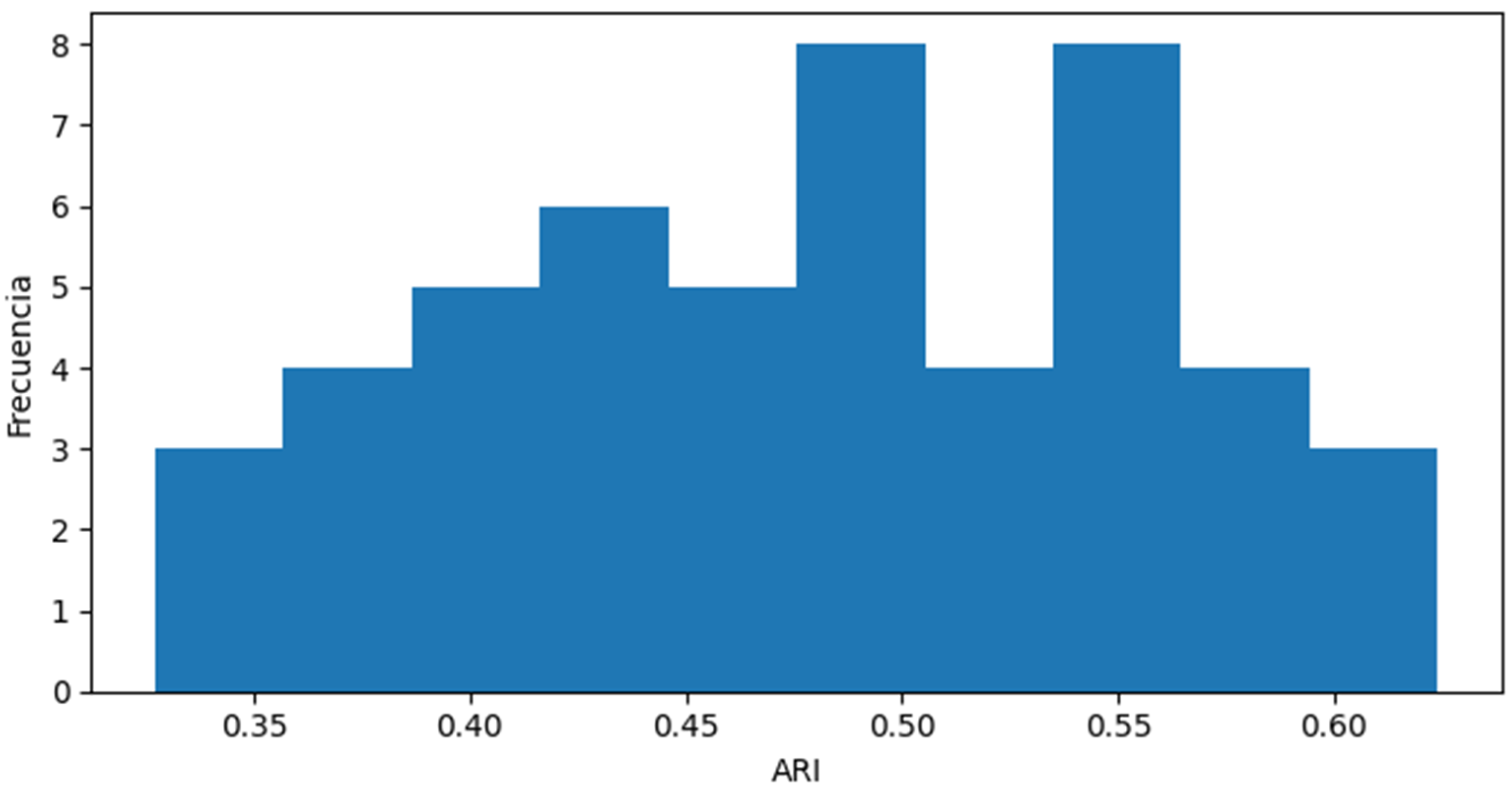

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Organisational Archetypes and Theoretical Convergences

4.2. Explanatory Factors, the Circular Paradox, and Environmental Implications

4.3. Policy Implications, Limitations, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| CE | Circular economy |

| CWE | Circular water economy |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| GMM-LPA | Gaussian Mixture Model–Latent Profile Analysis |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| ARI | Adjusted Rand Index |

| NGO | Non-governmental organisation |

References

- Avdiushchenko, A.; Meinrenken, C.J. Circular economy concepts for accelerating sustainable urban transformation: The case of New York City. Cities 2025, 166, 106223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajanayake, A.; Iyer-Raniga, U. If there is waste, there is a system: Understanding Victoria’s circular economy transition from a systems thinking perspective. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 227, 108395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy: A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damman, S.; Schmuck, A.; Oliveira, R.; Koop, S.H.A.; Almeida, M.C.; Alegre, H.; Ugarelli, R.M. Towards a water-smart society: Progress in linking theory and practice. Util. Policy 2023, 85, 101674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran-Romero, D.; Barquet, K. Business models for decentralized water services in urban and peri-urban areas. Clean. Water 2025, 4, 100138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palea, V.; Migliavacca, A.; Gordano, S. Scaling up the transition: The role of corporate governance mechanisms in promoting circular economy strategies. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voorwinden, A.; van Bueren, E.; Verhoef, L. Experimenting with collaboration in the Smart City: Legal and governance structures of Urban Living Labs. Gov. Inf. Q. 2023, 40, 101875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaculíková, Z.; Ramkissoon, H.; Dey, S.K. Circular intentions, minimal actions: The psychology of doing less in hospitality—An integrative review. Acta Psychol. 2025, 259, 105267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K. Circular economy and the separated yet inseparable social dimension: Views from European circular city experts. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 51, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendrakumar, S.; Mavhaire, D.; Shimly, S.; Rahut, D.B.; Tharanidevi, N.; Ramachandran, V.S.; Timilsina, R.R. Drivers and barriers towards achieving SDG 6 on clean water and sanitation for all—An Indian perspective. World Dev. Sustain. 2025, 7, 100228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Kumar, S.; Huang, Z.; Liu, R. Water resource management and policy evaluation in Middle Eastern countries: Achieving Sustainable Development Goal 6. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 320, 100829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brears, R.C. Sustainable Water-Food Nexus: Circular Economy, Water Management, Sustainable Agriculture; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Ravi, K.; Wani, A.W.; Mhaske, T.; Qureshi, S.N. Wastewater resources management for energy recovery: The circular economy perspective. In Water Use Efficiency, Sustainability and the Circular Economy; Bandh, S.A., Malla, F.A., Halog, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mannina, G.; Cosenza, A.; Gulhan, H. Water reuse from treated wastewater: Insights gained from the Italian demonstration case studies of the Wider-Uptake EU project. In Boosting the Transition to Circular Economy in the Water Sector; Mannina, G., Pandey, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Shafik, W. Circular economy in the urban water sector: Challenges and opportunities. In Water Use Efficiency, Sustainability and the Circular Economy; Bandh, S.A., Malla, F.A., Halog, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oral, H.V.; Boyacıoğlu, H.; Alkaya, E.; Dolgen, D.; Bladen, T.; Bayırtepe, B.; Atayol, A.A.; Alpaslan, N.; Saygın, H. Water management and sustainable development: Circular water management conception on a river basin. In Water Use Efficiency, Sustainability and the Circular Economy; Bandh, S.A., Malla, F.A., Halog, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cosenza, A.; Mannina, G. Governance assessment and business models for reuse of treated wastewater in agriculture: An Italian case study. In Boosting the Transition to Circular Economy in the Water Sector; Mannina, G., Pandey, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Trapani, D.; Cosenza, A.; Gulhan, H.; Mannina, G. Roadmap development and preliminary applications to foster the transition to the circular economy in the water sector: The case study of Corleone. In Boosting the Transition to Circular Economy in the Water Sector; Mannina, G., Pandey, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandala, E.R. Sustainable developing goals: SDG 6 and its significance for sustainable growth. In Circular Economy Applications for Water Security; Bandala, E.R., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akon-Yamga, G.; Quaye, W.; Essegbey, G.O.; Oduro, W.O.; Issahaku, A.; Onumah, J.A.; Williams, P.A.; Mahama, A. Fuel production from sewage sludge: Insights from a demonstration in Ghana. In Boosting the Transition to Circular Economy in the Water Sector; Mannina, G., Pandey, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Corsini, F.; Fontana, S.; Gusmerotti, N.M.; Iovino, R.; Iraldo, F.; Mecca, D.; Ruini, L.F.; Testa, F. Bridging gaps in the demand and supply for circular economy: Empirical insights into the symbiotic roles of consumers and manufacturing companies. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2024, 15, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Schmid, A.; Vásquez-Ibarra, L.; Guerrero, A.B.; Henninger, C.E.; Rebolledo-Leiva, R. Circular economy in a recently transitioned high-income country in Latin America and the Caribbean: Barriers, drivers, strengths, opportunities, key stakeholders and priorities in Chile. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 486, 144429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikelenboom, M.; van Marrewijk, A. Creating points of opportunity in sustainability transitions: Reflective interventions in inter-organizational collaboration. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2023, 48, 100748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, D.; Raven, R.; Farrelly, M. Pluralising place frames in urban transition management: Net-zero transitions at precinct scale. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2024, 50, 100803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, T.B.J.; Wiarda, M.; Visscher, K.; Penna, C.C.R.; Volker, L. Mission-Oriented Transition Assessment as a reflective approach to mission governance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 219, 124257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasinghe, I.; Stewart, R.A.; Sahin, O.; Liu, T. Enhancing construction material circularity: An integrated participatory systems model. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2025, 57, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijaya, A.; Qadri, F.D.; Angreani, L.S.; Wicaksono, H. ESGOnt: An ontology-based framework for enhancing Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) assessments and aligning with Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2025, 22, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncube, K. Sustainable communal septic tank systems in informal settlements: The case of Lebak Siliwangi, Indonesia. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2025, 23, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirumalla, K.; Balestrucci, F.; Sannö, A.; Oghazi, P. The transition from a linear to a circular economy through a multi-level readiness framework: An explorative study in the heavy-duty vehicle manufacturing industry. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, D.J.; Rosca, E.; Angelopoulos, M.; Kamminga, O.; Hooijer, C. Orchestrating a smart circular economy: Guiding principles for digital product passports. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 169, 114259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bais, B.; Molinaro, M.; Orzes, G. Assessing circular economy at company level: Comparison of tools and methodological challenges. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2025, 59, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schild, C.; Holly, F. Development of a framework for circular economy assessment: Indicators for circular value chains. Procedia CIRP 2025, 135, 1076–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofiyah, E.S.; Sianipar, I.M.J.; Rahman, A.; Caesarina, N.P.; Suhardono, S.; Suryawan, I.W.K.; Lee, C.H. Adaptive governance in the water-energy-food-ecosystem nexus for sustainable community sanitation. World Dev. Sustain. 2025, 6, 100220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Haddid, O.; Ahmad, A.; AbedRabbo, M. Unlocking water sustainability: The role of knowledge, attitudes, and practices among women. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 476, 143697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mango, F.; Vincent, R.C. Does polycentric climate governance drive the circular economy? Evidence from subnational spending and dematerialization of production in the EU. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 231, 108533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halidu, O.B.; Mwesigwa, R.; Alinda, K.; Tumwine, S.; Lwanga, F. Industrial circular ecosystem entrant: Examining small firms. Manag. Decis. 2025, 63, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Kumar, A.; Sassanelli, C.; Kumar, L. Exploring the role of finance in driving circular economy and sustainable business practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 486, 144480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariyani, D.; Hariyani, P.; Mishra, S. Digital technologies for the Sustainable Development Goals. Green Technol. Sustain. 2025, 3, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.S.; Ahmad, M.O.; Majava, J. Industry 4.0 innovations and their implications: An evaluation from sustainable development perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 405, 137006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, P.F. The circular economy concept and its application to SDG 6. In Circular Economy Applications for Water Security; Bandala, E.R., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazi, F.; Fidélis, T.; Teles, F. Fostering the transition to water reuse: The role of institutional arrangements in the European Union circular economy action plans. In Water Management and Circular Economy; Zamparas, M.G., Kyriakopoulos, G.L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ocampo, H.; Katusic, V.; Demetriou, G. Closing the loop in water management. In Water Management and Circular Economy; Zamparas, M.G., Kyriakopoulos, G.L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidélis, T.; Matos, M.V.; de Sousa, M.C.; Miranda, A.C.; Riazi, F.; Teles, F.; Capela, I. Assessing policy and planning contexts for the transition to water circular economy: Examples from Southern Europe. In Water Management and Circular Economy; Zamparas, M.G., Kyriakopoulos, G.L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 113–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakopoulos, G.L. Circular economy and sustainable strategies: Theoretical framework, policies and regulation challenges, barriers, and enablers for water management. In Water Management and Circular Economy; Zamparas, M.G., Kyriakopoulos, G.L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 197–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, S.; Lakhwan, N.; Bharat, G.K. Circular economy in water management as a driver to sustainable businesses. In Water Use Efficiency, Sustainability and the Circular Economy; Bandh, S.A., Malla, F.A., Halog, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, L.; Sowjanya, S.; Chakraborty, A.; Amrit, R.; Nurgat, M.Z.; Dutta, P.; Das, P.; Das, A.; Sivarajan, S.; Wagh, M. Economic, environmental, and social optimization of wastewater management in the context of circular economy. In Water Use Efficiency, Sustainability and the Circular Economy; Bandh, S.A., Malla, F.A., Halog, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 203–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryan, Y.; Nagare, N.; Dikshit, A.K.; Shinde, A.M. Circular economy in developing countries: Present status, pathways, benefits, and challenges. In Circular Economy: Applications for Water Remediation; Shah, M.P., Manna, S., Das, P., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amesho, K.T.T.; Shopati, A.K.; Shangdiar, S.; Kadhila, T.; Iikela, S.; Sithole, N.T.; Edoun, E.I.; Chowdhury, S. Integrating circular economy and sustainability strategy in water remediation applications. In Circular Economy: Applications for Water Remediation; Shah, M.P., Manna, S., Das, P., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhambhani, A.; Kapelan, Z. Circularity and efficiency assessment of resource recovery solutions. In Boosting the Transition to Circular Economy in the Water Sector: Insights from EU Demonstration Case Studies; Mannina, G., Pandey, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renfrew, D.; Nika, E.; Vasilaki, V.; Katsou, E. Selecting resource recovery technologies and assessment of impacts. In Water Management and Circular Economy; Zamparas, M.G., Kyriakopoulos, G.L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalavrouziotis, I.K.; Kyritsis, S.S.; Koukoulakis, P.H. Benefits from reclaimed wastewater and biosolid reuse in agriculture and in the environment. In Water Management and Circular Economy; Zamparas, M.G., Kyriakopoulos, G.L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 273–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, G.J.; Peel, D. Finite Mixture Models; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann. Stat. 1978, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Biswas, S. Circular economy in urban wastewater management: A concise review. In Circular Economy: Applications for Water Remediation; Shah, M.P., Manna, S., Das, P., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosenza, A.; Di Trapani, D.; Ugarelli, R.; Helness, H.; Mannina, G. Scenario analysis toward the implementation of a roadmap for transitioning to a circular economy in the case study of Corleone. In Boosting the Transition to Circular Economy in the Water Sector; Mannina, G., Pandey, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Questioning |

|---|---|

| 1 | Our organisation has adequate financial resources to invest in water reuse technologies |

| 2 | The costs of implementing reuse technologies are within our budgetary means |

| 3 | Senior management demonstrates visible commitment to the implementation of water reuse technologies |

| 4 | Organisational leaders actively communicate the importance of the circular water economy |

| 5 | There is a well-established culture of environmental responsibility in our organisation |

| 6 | Organisational values explicitly include sustainability and water conservation |

| 7 | We have technical staff who are sufficiently trained to operate reuse technologies |

| 8 | I believe that reuse technologies represent essential innovations for the future |

| 9 | I am genuinely motivated to lead the adoption of innovative environmental technologies |

| 10 | The economic and environmental benefits far outweigh the potential risks |

| 11 | I have complete confidence in the safety and effectiveness of modern reuse systems |

| 12 | In my sector, it is increasingly common and expected to adopt reuse technologies |

| 13 | There is a growing social expectation that we adopt circular economy practices |

| 14 | I have a solid understanding of the technologies available for water reuse |

| 15 | I clearly understand the technical and economic benefits of these technologies |

| 16 | Current regulations effectively facilitate the implementation of reuse technologies |

| 17 | The legal requirements for water reuse are clear, consistent, and achievable |

| 18 | There are attractive government economic incentives to adopt reuse technologies |

| 19 | Public policies effectively and consistently promote the circular water economy |

| 20 | In my sector, there is growing regulatory pressure to implement sustainable practices |

| 21 | Industry standards are progressively demanding greater efficiency in water use |

| 22 | Public institutions provide competent and timely technical advice |

| 23 | Our organisation has successfully implemented functional water reuse systems |

| 24 | We regularly use advanced treatment technologies for internal reuse |

| 25 | We have concrete and funded strategic plans to expand reuse |

| 26 | We systematically monitor and optimise our reuse systems |

| 27 | The systems implemented consistently exceed performance expectations |

| 28 | We have achieved significant quantifiable reductions in fresh water consumption |

| 29 | The implementation has generated measurable and substantial economic savings |

| 30 | Our stakeholders recognise and value our achievements in circular water economy |

| Domain | Ítems |

| Resources | 1, 2 |

| Leadership | 3, 4 |

| Culture | 5, 6 |

| Capabilities/Tech | 7, 8, 9, 10 |

| Competition | 11, 12 |

| Suppliers | 13, 14, 15 |

| Regulation/Support | 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 |

| Implementation | 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 |

| Results | 28, 29, 30 |

| Cluster | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resources | 3.92 | 1.65 | 5.00 | 3.07 | 2.21 | 2.18 | 4.17 | 3.56 |

| Leadership | 4.22 | 1.70 | 5.00 | 3.38 | 2.55 | 2.05 | 4.31 | 3.62 |

| Culture | 4.39 | 1.85 | 4.94 | 3.64 | 2.74 | 2.91 | 4.14 | 3.83 |

| Capabilities/Tech | 3.94 | 1.64 | 4.72 | 4.26 | 3.12 | 3.74 | 4.38 | 3.81 |

| Competition | 3.72 | 1.60 | 4.94 | 4.19 | 3.08 | 3.66 | 4.33 | 3.90 |

| Suppliers | 3.70 | 1.47 | 4.92 | 4.35 | 3.05 | 3.67 | 4.44 | 3.93 |

| Regulation/Support | 2.85 | 1.80 | 4.93 | 3.62 | 3.18 | 2.74 | 4.23 | 3.79 |

| Implementation | 3.52 | 1.70 | 4.95 | 3.04 | 3.15 | 1.60 | 4.32 | 3.90 |

| Results | 3.54 | 1.65 | 4.88 | 3.03 | 3.05 | 2.15 | 4.56 | 4.10 |

| K | BIC | AIC | Silhouette | MinCluster_n | ARI (K = 6 vs. K = 8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 7128.615079 | −1828.024921 | 0.143046 | 19 | 0.552 |

| 8 | 3965.785325 | −7977.404886 | 0.120439 | 8 | 0.552 |

| Evidence | Main Result | Interpretation for Results |

|---|---|---|

| Crosswalk (K = 8 → K = 6 structure) | K6 = 0 aggregates K8 = [6, 2]; K6 = 4 aggregates K8 = [7, 3]; near 1–1 correspondences: K6 = 1 → K8 = 1; K6 = 5 → K8 = 5; K6 = 3 → K8 = 0; K6 = 2 → K8 = 4. | K = 8 refines two substantively relevant segments into sub-classes while preserving the overall structure; K = 6 acts as a parsimonious version. |

| Most discriminating domains (between-profile variance) | K = 6: Leadership (1.393), Implementation (1.326), Resources (1.271), Results (1.224). K = 8: Implementation (1.387), Leadership (1.362), Resources (1.322), Results (1.269). | Class differentiation is primarily organised by Implementation and Leadership, followed by Resources and Results; the pattern is stable across K. |

| Archetype robustness (4 archetypes) | ARI(archetypes) = 0.631 (K = 6 vs. K = 8); diagonal-dominant mapping (main diagonal counts: 39, 51, 20, 19). | The macro-level interpretation in four archetypes remains stable; K = 8 adds within-archetype granularity without changing the overarching logic. |

| Associations with performance (Spearman) | Implementation: Leadership ρ = 0.713; Culture ρ = 0.560; Regulation/Support ρ = 0.701. Results: Leadership ρ = 0.719; Culture ρ = 0.585; Regulation/Support ρ = 0.679. N = 150, p < 0.001. | Leadership and Regulation/Support show strong monotonic associations with Implementation and Results; reported as correlational support consistent with the profiles. |

| Characteristic | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic location | Lima | 68 | 45.3 |

| Trujillo | 49 | 32.7 | |

| Cajamarca | 33 | 22.0 | |

| Organisation type | Public utility (EPS) | 42 | 28.0 |

| Private company | 58 | 38.7 | |

| Public entity/Municipality | 31 | 20.7 | |

| NGO/Foundation | 19 | 12.7 | |

| Organisation size (employees) | Micro (1–10) | 27 | 18.0 |

| Small (11–50) | 48 | 32.0 | |

| Medium (51–250) | 52 | 34.7 | |

| Large (>250) | 23 | 15.3 | |

| Years of operation | <5 years | 22 | 14.7 |

| 5–10 years | 35 | 23.3 | |

| 11–20 years | 51 | 34.0 | |

| >20 years | 42 | 28.0 | |

| Primary sector of activity | Water supply/sanitation | 54 | 36.0 |

| Manufacturing/Industry | 38 | 25.3 | |

| Agriculture/Agroindustry | 29 | 19.3 | |

| Mining/Extractive | 17 | 11.3 | |

| Services/Other | 12 | 8.0 | |

| Respondent position | Senior management | 47 | 31.3 |

| Middle management | 68 | 45.3 | |

| Technical specialist | 35 | 23.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vera-Zelada, P.; Ríos-Villacorta, M.A.; Licapa-Redolfo, G.S.; Licapa-Redolfo, R.; Aranguri-Cayetano, D.J.; Castillo-Chung, A.R.; Haro-Sarango, A.F.; Ramos-Farroñán, E.V. Discovering Organisational Leadership Archetypes in Peru’s Circular Water Economy Using Latent Class Analysis. Environments 2026, 13, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13020074

Vera-Zelada P, Ríos-Villacorta MA, Licapa-Redolfo GS, Licapa-Redolfo R, Aranguri-Cayetano DJ, Castillo-Chung AR, Haro-Sarango AF, Ramos-Farroñán EV. Discovering Organisational Leadership Archetypes in Peru’s Circular Water Economy Using Latent Class Analysis. Environments. 2026; 13(2):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13020074

Chicago/Turabian StyleVera-Zelada, Persi, Mauro Adriel Ríos-Villacorta, Gladys Sandi Licapa-Redolfo, Rolando Licapa-Redolfo, Denis Javier Aranguri-Cayetano, Aldo Roger Castillo-Chung, Alexander Fernando Haro-Sarango, and Emma Verónica Ramos-Farroñán. 2026. "Discovering Organisational Leadership Archetypes in Peru’s Circular Water Economy Using Latent Class Analysis" Environments 13, no. 2: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13020074

APA StyleVera-Zelada, P., Ríos-Villacorta, M. A., Licapa-Redolfo, G. S., Licapa-Redolfo, R., Aranguri-Cayetano, D. J., Castillo-Chung, A. R., Haro-Sarango, A. F., & Ramos-Farroñán, E. V. (2026). Discovering Organisational Leadership Archetypes in Peru’s Circular Water Economy Using Latent Class Analysis. Environments, 13(2), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13020074