Balancing Durability and Sustainability: Field Performance of Plastic and Biodegradable Materials in Eastern Oyster Breakwater Reef Restoration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

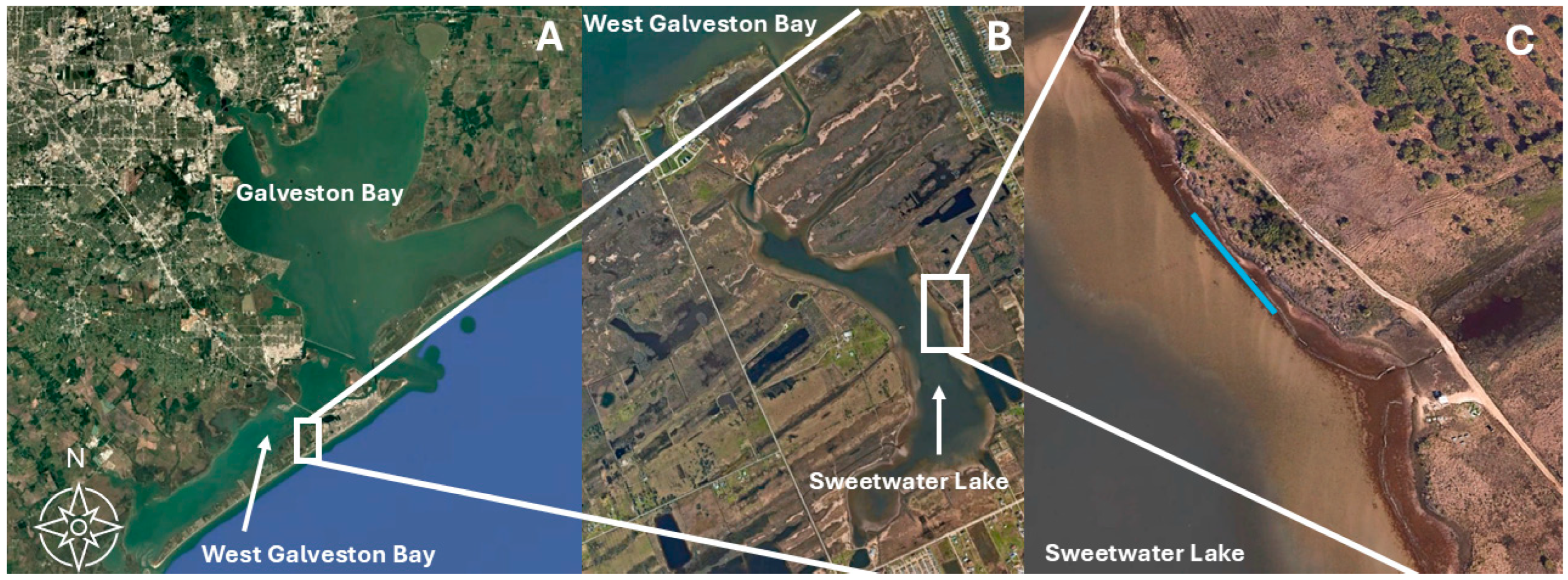

2.1. Study Site and Bag Deployment

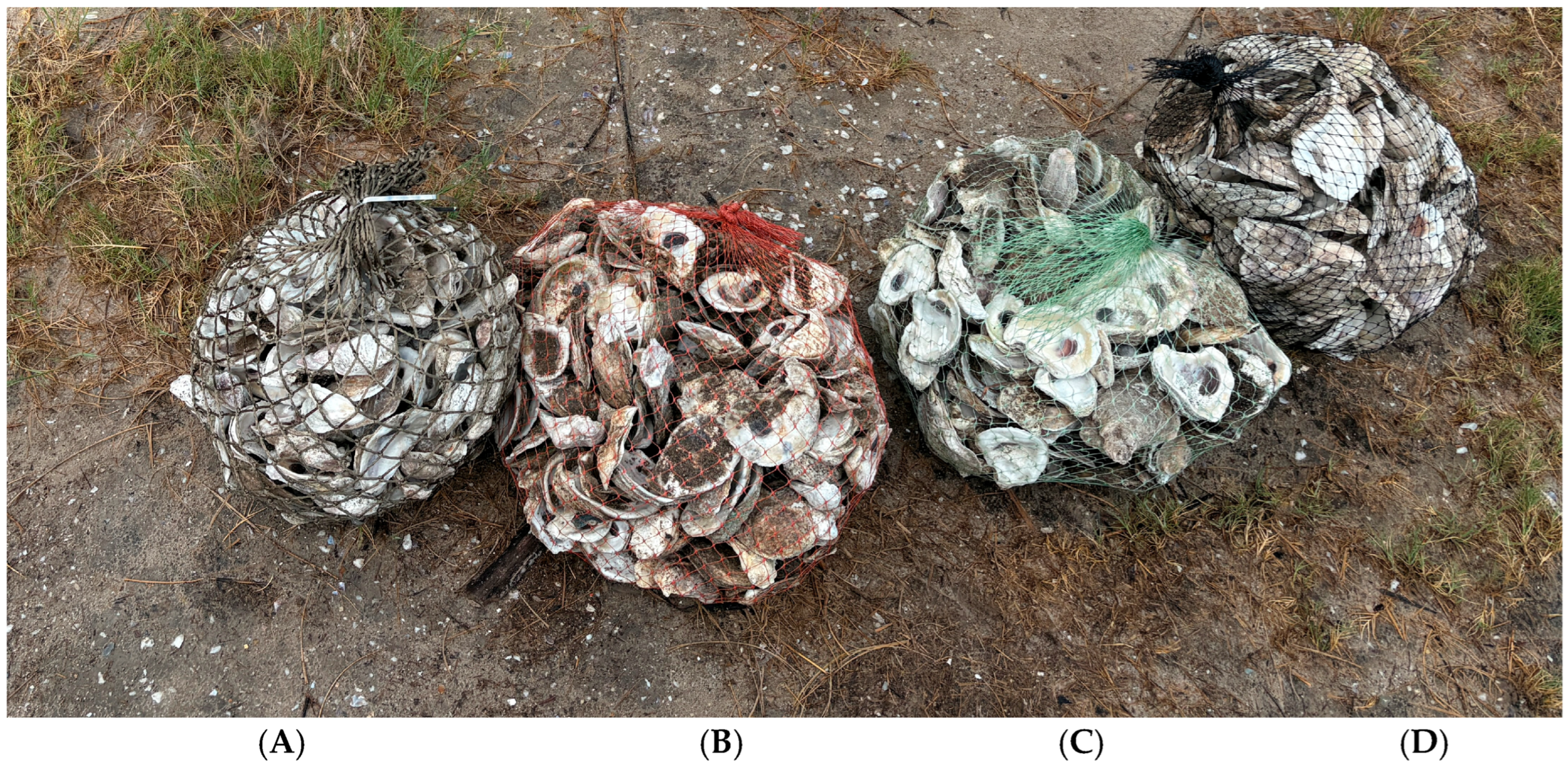

2.2. Assessment of Bag Types

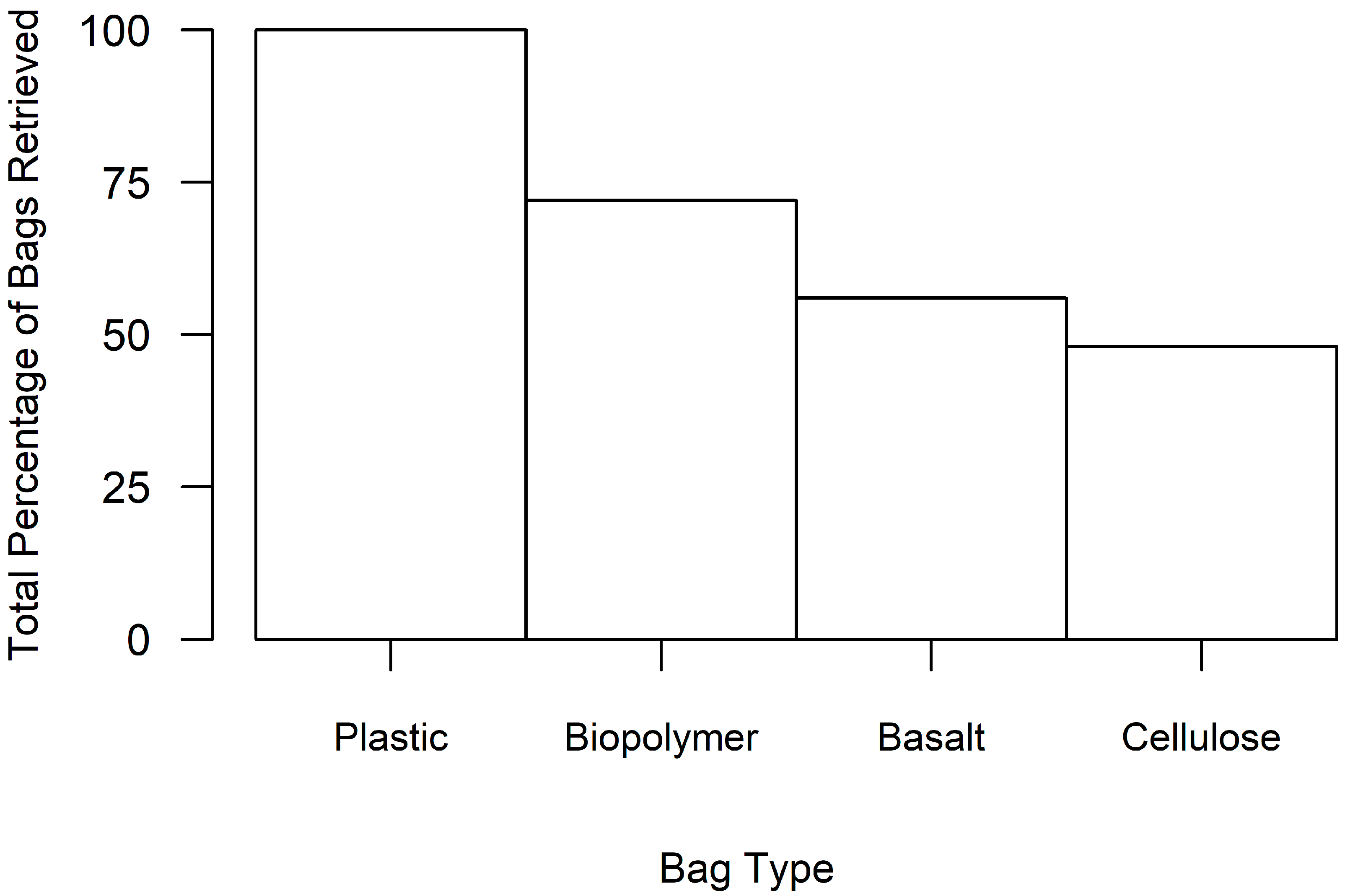

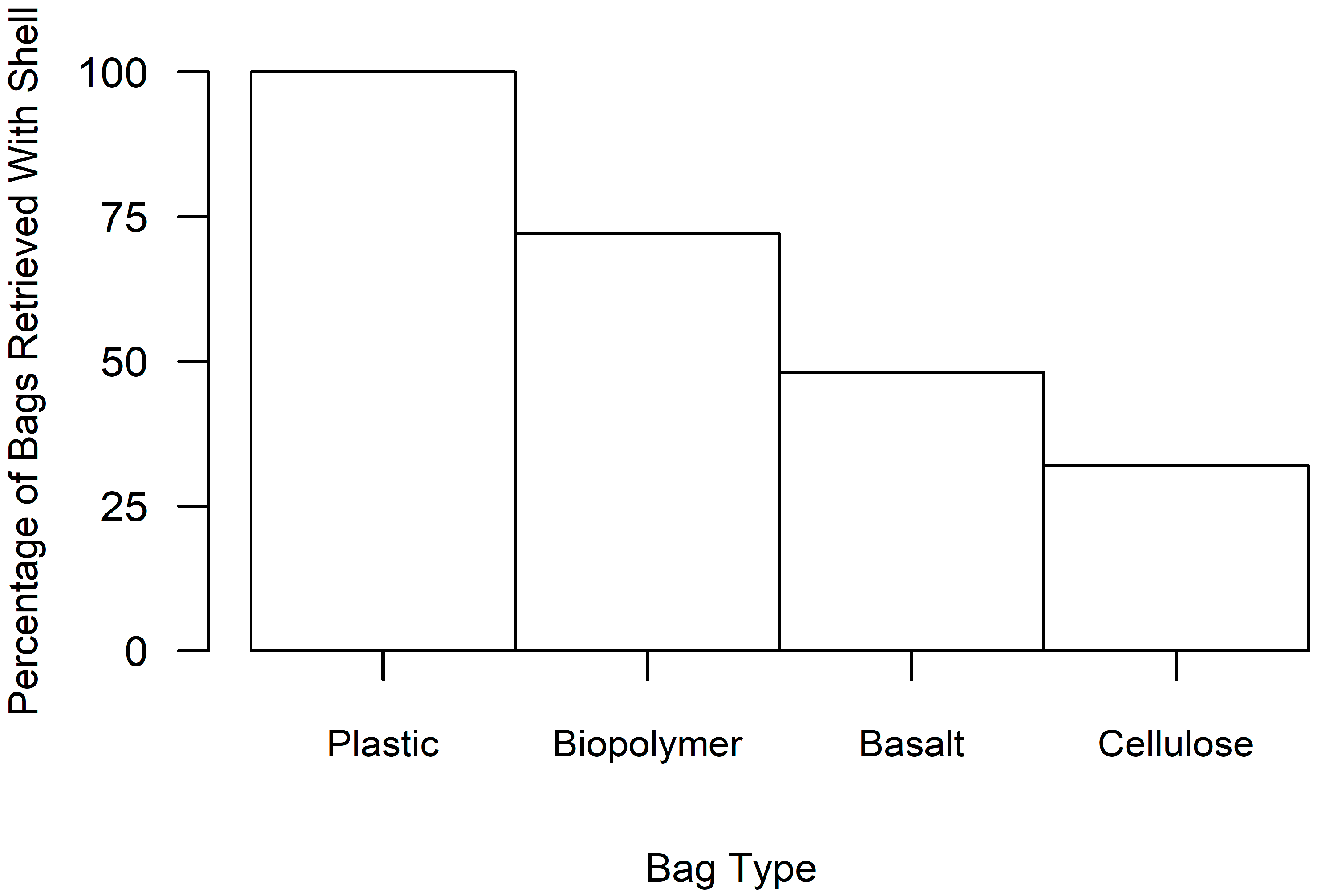

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Deployment Duration | Plastic | Biopolymer | Basalt | Cellulose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ~4 months | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ~7 months | 7 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| 10–11 months | 16 | 14 | 7 | 4 |

| Total | 25 | 18 | 12 | 7 |

| Bag Material | Cost of 25 Bags (in USD) | Deployment Costs (in USD) | Retrieval Costs (in USD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plastic | 66.00 | 556.64 | 67.14 |

| Biopolymer | 38.75 | 556.64 | 88.35 |

| Basalt | 612.75 | 278.32 | 119.90 |

| Cellulose | 50.00 | 556.64 | 186.51 |

References

- Levinton, J.; Doall, M.; Allam, B. Growth and Mortality Patterns of the Eastern Oyster Crassostrea virginica in Impacted Waters in Coastal Waters in New York, USA. J. Shellfish Res. 2013, 32, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, L.J.; Sacks, P.E.; Bobo, M.Y.; Richardson, D.L.; Coen, L.D. Impact of Hurricanes and Boat Wakes on Intertidal Oyster Reefs in the Indian River Lagoon: Reef Profiles and Disease Prevalence. Fla. Sci. 2007, 700, 506–521. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Park, K.; Jensen, C.; Dellapenna, T.M.; Zhang, W.G.; Shi, Y. Massive Oyster Kill in Galveston Bay Caused by Prolonged Low-Salinity Exposure after Hurricane Harvey. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 774, 145132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenihan, H.S.; Micheli, F.; Shelton, S.W.; Peterson, C.H. The Influence of Multiple Environmental Stressors on Susceptibility to Parasites: An Experimental Determination with Oysters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1999, 44, 910–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenihan, H.; Peterson, C. How Habitat Degradation through Fishery Disturbance Enhances Impacts of Hypoxia on Oyster Reefs. Ecol. Appl. 1998, 8, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.W.; Brumbaugh, R.D.; Airoldi, L.; Carranza, A.; Coen, L.D.; Crawford, C.; Defeo, O.; Edgar, G.J.; Hancock, B.; Kay, M.C.; et al. Oyster Reefs at Risk and Recommendations for Conservation, Restoration, and Management. Bioscience 2011, 61, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okon, E.M.; Birikorang, H.N.; Munir, M.B.; Kari, Z.A.; Téllez-Isaías, G.; Khalifa, N.E.; Abdelnour, S.A.; Eissa, M.E.H.; Al-Farga, A.; Dighiesh, H.S.; et al. A Global Analysis of Climate Change and the Impacts on Oyster Diseases. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, D.M. History of the Virginia Oyster Fishery, Chesapeake Bay, USA. Front. Mar. Sci. 2017, 4, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, C. Causes Underlying the Historical Decline in Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica Gmelin, 1791) Landings. J. Shellfish Res. 2007, 26, 927–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellei, P.; Torres, I.; Solstad, R.; Flores-Colen, I. Potential Use of Oyster Shell Waste in the Composition of Construction Composites: A Review. Buildings 2023, 13, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Park, S.; Lee, K.; Park, J. Oyster Shell as Substitute for Aggregate in Mortar. Waste Manag. Res. 2004, 22, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanke, M.H.; Bobby, N.; Sanchez, R. Can Relic Shells Be an Effective Settlement Substrate for Oyster Reef Restoration? Restor. Ecol. 2021, 29, e13371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, V.D.; Rick, T.; Garland, C.J.; Thomas, D.H.; Smith, K.Y.; Bergh, S.; Sanger, M.; Tucker, B.; Lulewicz, I.; Semon, A.M.; et al. Ecosystem Stability and Native American Oyster Harvesting along the Atlantic Coast of the United States. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba9652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitburg, D.L.; Coen, L.D.; Luckenbach, M.W.; Mann, R.; Posey, M.; Wesson, J.A. Oyster Reef Restoration: Convergence of Harvest and Conservation Strategies. J. Shellfish Res. 2000, 19, 371–377. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, E.N.; Morson, J.M.; Ashton-Alcox, K.A.; Kim, Y. Accommodation of the Sex-Ratio in Eastern Oysters Crassostrea Virginica to Variation in Growth and Mortality across the Estuarine Salinity Gradient. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2013, 93, 533–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, E.N.; Klinck, J.M.; Ashton-Alcox, K.A.; Kraeuter, J.N. Multiple Stable Reference Points in Oyster Populations: Implications for Reference Point-Based Management. Fish. Bull. 2009, 107, 133–147. [Google Scholar]

- Hanke, M.H.; Leija, H.; Laroche, R.A.S.; Modi, S.; Culver-Miller, E.; Sanchez, R.; Bobby, N. Localized Placement of Breakwater Reefs Influences Oyster Populations and Their Resilience after Hurricane Harvey. Ecologies 2022, 3, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oldenborgh, G.J.; van der Wiel, K.; Sebastian, A.; Singh, R.; Arrighi, J.; Otto, F.; Haustein, K.; Li, S.; Vecchi, G.; Cullen, H. Attribution of Extreme Rainfall from Hurricane Harvey, August 2017. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 124009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyng, K.M.; Hetland, R.D.; Socolofsky, S.A.; Fernando, N.; Turner, E.L.; Schoenbaechler, C. Hurricane Harvey Caused Unprecedented Freshwater Inflow to Galveston Bay. Estuaries Coasts 2020, 43, 1836–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, P.M.; Palmer, T.A.; Beseres Pollack, J. Oyster Reef Restoration: Substrate Suitability May Depend on Specific Restoration Goals. Restor. Ecol. 2017, 25, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goelz, T.; Vogt, B.; Hartley, T. Alternative Substrates Used for Oyster Reef Restoration: A Review. J. Shellfish Res. 2020, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coen, L.D.; Luckenbach, M.W. Developing Success Criteria and Goals for Evaluating Oyster Reef Restoration: Ecological Function or Resource Exploitation? Ecol. Eng. 2000, 15, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckenbach, M.W.M.; Coen, L.D.L.; Ross, P.G., Jr.; Stephen, J.A.J. Oyster Reef Habitat Restoration: Relationships between Oyster Abundance and Community Development Based on Two Studies in Virginia and South Carolina. J. Coast. Res. 2005, 40, 64–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lipcius, R.N.; Burke, R.P.; McCulloch, D.N.; Schreiber, S.J.; Schulte, D.M.; Seitz, R.D.; Shen, J. Overcoming Restoration Paradigms: Value of the Historical Record and Metapopulation Dynamics in Native Oyster Restoration. Front. Mar. Sci. 2015, 2, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggett, L.P.; Powers, S.P.; Brumbaugh, R.D.; Coen, L.D.; Deangelis, B.M.; Greene, J.K.; Hancock, B.T.; Morlock, S.M.; Allen, B.L.; Breitburg, D.L.; et al. Guidelines for Evaluating Performance of Oyster Habitat Restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2015, 23, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coen, L.; Brumbaugh, R.; Bushek, D.; Grizzle, R.; Luckenbach, M.; Posey, M.; Powers, S.; Tolley, S. Ecosystem Services Related to Oyster Restoration. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2007, 341, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.R.; Pollack, J.; Fox, J.M.; Ferreira, J.G.; Cubillo, A.M.; Reisinger, A.; Bricker, S. Developing Nitrogen Bioextraction Economic Value via Off-Bottom Oyster Aquaculture in the Northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 211, 117396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, L.M.; De Santiago, K.; Palmer, T.A.; Beseres Pollack, J. Oyster Reef Restoration: Effect of Alternative Substrates on Oyster Recruitment and Nekton Habitat Use. J. Coast. Conserv. 2015, 19, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, D.L.; Townsend, E.C.; Thayer, G.W. Stabilization and Erosion Control Value of Oyster Cultch for Intertidal Marsh. Restor. Ecol. 1997, 5, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke, M.H.; Posey, M.H.; Alphin, T.D. The Influence of Habitat Characteristics on Intertidal Oyster Crassostrea virginica Populations. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2017, 571, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caretti, O.N.; Bohnenstiehl, D.W.R.; Eggleston, D.B. Spatiotemporal Variability in Sedimentation Drives Habitat Loss on Restored Subtidal Oyster Reefs. Estuaries Coasts 2021, 44, 2100–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, L.A.; Clements, J.C.; Davidson, J.D.P.; Miron, G.; Davidson, J.; Comeau, L.A. Sink before You Settle: Settlement Behaviour of Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica) Larvae on Artificial Spat Collectors and Natural Substrate. Aquac. Rep. 2019, 13, 100181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushek, D.; Richardson, D.; Bobo, M.Y.; Coen, L.D. Quarantine of Oyster Shell Cultch Reduces the Abundance of Perkinsus Marinus. J. Shellfish Res. 2004, 23, 369–373. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel, S.D.; Prevost, H.J.; Knoell, A.; Marcum, P.; Dix, N. Spatial and Temporal Variability in Oyster Settlement on Intertidal Reefs Support Site-Specific Assessments for Restoration Practices. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, E.N.; White, M.E.; Wilson, E.A.; Ray, S.M. Small-Scale Spatial Distribution of Oysters (Crassostrea virginica) on Oyster Reefs. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1987, 41, 835–855. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, R.P.; Eggleston, D.B.; Lindquist, N. Effects of Substrate Type on Demographic Rates of Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica). J. Shellfish Res. 2014, 33, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.J.; Smith, K.J.; Hargis, C.W. Development of Pervious Oyster Shell Habitat (POSH) Concrete for Reef Restoration and Living Shorelines. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 295, 123685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grizzle, R.E.; Brodeur, M.A.; Abeels, H.A.; Greene, J.K. Bottom Habitat Mapping Using Towed Underwater Videography: Subtidal Oyster Reefs as an Example Application. J. Coast. Res. 2008, 24, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scyphers, S.B.; Powers, S.P.; Heck, K.L. Ecological Value of Submerged Breakwaters for Habitat Enhancement on a Residential Scale. Environ. Manag. 2015, 55, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.S.N.; Hossain, M.S.; Ysebaert, T.; Smaal, A.C. Do Oyster Breakwater Reefs Facilitate Benthic and Fish Fauna in a Dynamic Subtropical Environment? Ecol. Eng. 2020, 142, 105635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.S.N.; Walles, B.; Sharifuzzaman, S.; Shahadat Hossain, M.; Ysebaert, T.; Smaal, A.C. Oyster Breakwater Reefs Promote Adjacent Mudflat Stability and Salt Marsh Growth in a Monsoon Dominated Subtropical Coast. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.L.; La Peyre, M.K.; Webb, B.M.; Marshall, D.A.; Bilkovic, D.M.; Cebrian, J.; McClenachan, G.; Kibler, K.M.; Walters, L.J.; Bushek, D.; et al. Large-scale Variation in Wave Attenuation of Oyster Reef Living Shorelines and the Influence of Inundation Duration. Ecol. Appl. 2021, 31, e2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manis, J.E.; Garvis, S.K.; Jachec, S.M.; Walters, L.J. Wave Attenuation Experiments over Living Shorelines over Time: A Wave Tank Study to Assess Recreational Boating Pressures. J. Coast. Conserv. 2015, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comba, D.; Palmer, T.A.; Breaux, N.J.; Pollack, J.B. Evaluating Biodegradable Alternatives to Plastic Mesh for Small-Scale Oyster Reef Restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2023, 31, e13762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.L.; Bilkovic, D.M.; Boswell, M.K.; Bushek, D.; Cebrian, J.; Goff, J.; Kibler, K.M.; La Peyre, M.K.; McClenachan, G.; Moody, J.; et al. The Application of Oyster Reefs in Shoreline Protection: Are We over-Engineering for an Ecosystem Engineer? J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 56, 1703–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, B.P.; Banks, P.D.; La Peyre, M.K. The Potential for Created Oyster Shell Reefs as a Sustainable Shoreline Protection Strategy in Louisiana. Restor. Ecol. 2005, 13, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Peyre, M.; Furlong, J.; Brown, L.A.; Piazza, B.P.; Brown, K. Oyster Reef Restoration in the Northern Gulf of Mexico: Extent, Methods and Outcomes. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2014, 89, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scyphers, S.B.; Powers, S.P.; Heck, K.L.; Byron, D. Oyster Reefs as Natural Breakwaters Mitigate Shoreline Loss and Facilitate Fisheries. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinn, J.P.; Bredes, A.; Bushek, D.; Kerr, L.; Kreeger, D.; McCulloch, D.; Miller, J.; Moody, J.; Rothermel, E.; Zito-Livingston, A. Seven Years of Monitoring the Development of an Oyster Reef Living Shoreline. Estuaries Coasts 2025, 48, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salatin, R.; Wang, H.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, L. Assessing Wave Attenuation With Rising Sea Levels for Sustainable Oyster Reef-Based Living Shorelines. Front. Built Environ. 2022, 8, 884849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumway, S.E.; Cucci, T.L.; Newell, R.C.; Yentsch, C.M. Particle Selection, Ingestion, and Absorption in Filter-Feeding Bivalves. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1985, 91, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bom, F.C.; Sá, F. Concentration of Microplastics in Bivalves of the Environment: A Systematic Review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussarellu, R.; Suquet, M.; Thomas, Y.; Lambert, C.; Fabioux, C.; Pernet, M.E.J.; Le Goïc, N.; Quillien, V.; Mingant, C.; Epelboin, Y.; et al. Oyster Reproduction Is Affected by Exposure to Polystyrene Microplastics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 2430–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.; Fan, C.; Liu, M.; Wolfe-Bryant, B. Effect of High-Density Polyethylene Microplastics on the Survival and Development of Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica) Larvae. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Sun, C.; He, C.; Li, J.; Ju, P.; Li, F. Microplastics in Four Bivalve Species and Basis for Using Bivalves as Bioindicators of Microplastic Pollution. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 782, 146830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baechler, B.R.; Granek, E.F.; Hunter, M.V.; Conn, K.E. Microplastic Concentrations in Two Oregon Bivalve Species: Spatial, Temporal, and Species Variability. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 2020, 5, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, L.J.; Roddenberry, A.; Crandall, C.; Wayles, J.; Donnelly, M.; Barry, S.C.; Clark, M.W.; Escandell, O.; Hansen, J.C.; Laakkonen, K.; et al. The Use of Non-Plastic Materials for Oyster Reef and Shoreline Restoration: Understanding What Is Needed and Where the Field Is Headed. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsch, C.K.; Walters, L.J.; Sacks, J.S.; Sacks, P.E.; Chambers, L.G. Biodegradable Material for Oyster Reef Restoration: First-Year Performance and Biogeochemical Considerations in a Coastal Lagoon. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Monreal, D.; Anis, A.; Salas-de-Leon, D.A. Galveston Bay Dynamics under Different Wind Conditions. Oceanologia 2018, 60, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulich, W.M.; White, W.A. Decline of Submerged Vegetation in the Galveston Bay System: Chronology and Relationships to Physical Processes. J. Coast. Res. 1991, 7, 1125–1138. [Google Scholar]

- LaRoche, R.A.; Doan, T.M.; Hanke, M.H. Habitat Characteristics of Artificial Oyster Reefs Influence Female Oystershell Mud Crab Panopeus simpsoni Rathbun, 1930 (Decapoda: Brachyura: Panopeidae). J. Crustac. Biol. 2022, 42, ruac033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke, M.H.; Hargrove, J.M.; Alphin, T.D.; Posey, M.H. Oyster Utilization and Host Variation of the Oyster Pea Crab (Zaops ostreum). J. Shellfish Res. 2015, 34, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, A.; Edwards, K.L. A State-of-the-Art Survey on the Influence of Normalization Techniques in Ranking: Improving the Materials Selection Process in Engineering Design. Mater. Des. 2015, 65, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantaphyllou, E.; Mann, S.H. An Examination of the Effectiveness of Multi-Dimensional Decision-Making Methods: A Decision-Making Paradox. Decis. Support Syst. 1989, 5, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; Ferreira, J.G.; Bricker, S.B.; DelValls, T.A.; Martín-Díaz, M.L.; Yáñez, E. Site Selection for Shellfish Aquaculture by Means of GIS and Farm-Scale Models, with an Emphasis on Data-Poor Environments. Aquaculture 2011, 318, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke, M.H.; Lambert, J.D.; Smith, K.J. Utilization of a Multicriteria Least Cost Path Model in an Aquatic Environment. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2014, 28, 1642–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamat, N.; Rasam, A.R.A.; Adnan, N.A.; Abdullah, I.C. GIS-Based Multi-Criteria Decision Making System for Determining Potential Site of Oyster Aquaculture in Terengganu. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 10th International Colloquium on Signal Processing and Its Applications, CSPA, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 7–9 March 2014; pp. 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke, M.H.; Posey, M.H.; Alphin, T.D. The Effects of Intertidal Oyster Reef Habitat Characteristics on Faunal Utilization. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2017, 581, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatchell, B.; Konchar, K.; Merrill, M.; Shea, C.; Smith, K. Use of Biodegradable Coir for Subtidal Oyster Habitat Restoration: Testing Two Reef Designs in Northwest Florida. Estuaries Coasts 2022, 45, 2675–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielski, M.; Hanke, M.; Jurgens, L.J.; Kamalanathan, M.; Mortuza, A.; Gahn, M.B.; Hala, D.; Kaiser, K.; Quigg, A. A Comparison of Methods to Quantify Nano- and/or Microplastic (NMPs) Deposition in Wild-Caught Eastern Oysters (Crassostrea virginica) Growing in a Heavily Urbanized, Subtropical Estuary (Galveston Bay, USA). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theuerkauf, S.J.; Puckett, B.J.; Eggleston, D.B. Metapopulation Dynamics of Oysters: Sources, Sinks, and Implications for Conservation and Restoration. Ecosphere 2021, 12, e03573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwell, M.W.; Veenstra, J.J.; Adams, C.D.; Scarlett, E.V.; Payne, K.B. Changes in Sediment Characteristics upon Oyster Reef Restoration, NE Florida, USA. J. Coast. Zone Manag. 2017, 20, 1000442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick-Ray, J. Historical Oyster Reef Connections to Chesapeake Bay—A Framework for Consideration. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2005, 64, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Koppel, J.; van der Heide, T.; Altieri, A.H.; Eriksson, B.K.; Bouma, T.J.; Olff, H.; Silliman, B.R. Long-Distance Interactions Regulate the Structure and Resilience of Coastal Ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2015, 7, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Bag Material | Source | Cost per Bag (in USD) |

|---|---|---|

| Plastic | masternetltd.com | 2.64 |

| Biopolymer | bese-products.com | 1.55 |

| Basalt | natrx.io | 24.51 |

| Cellulose | intermas.com | 2.00 * |

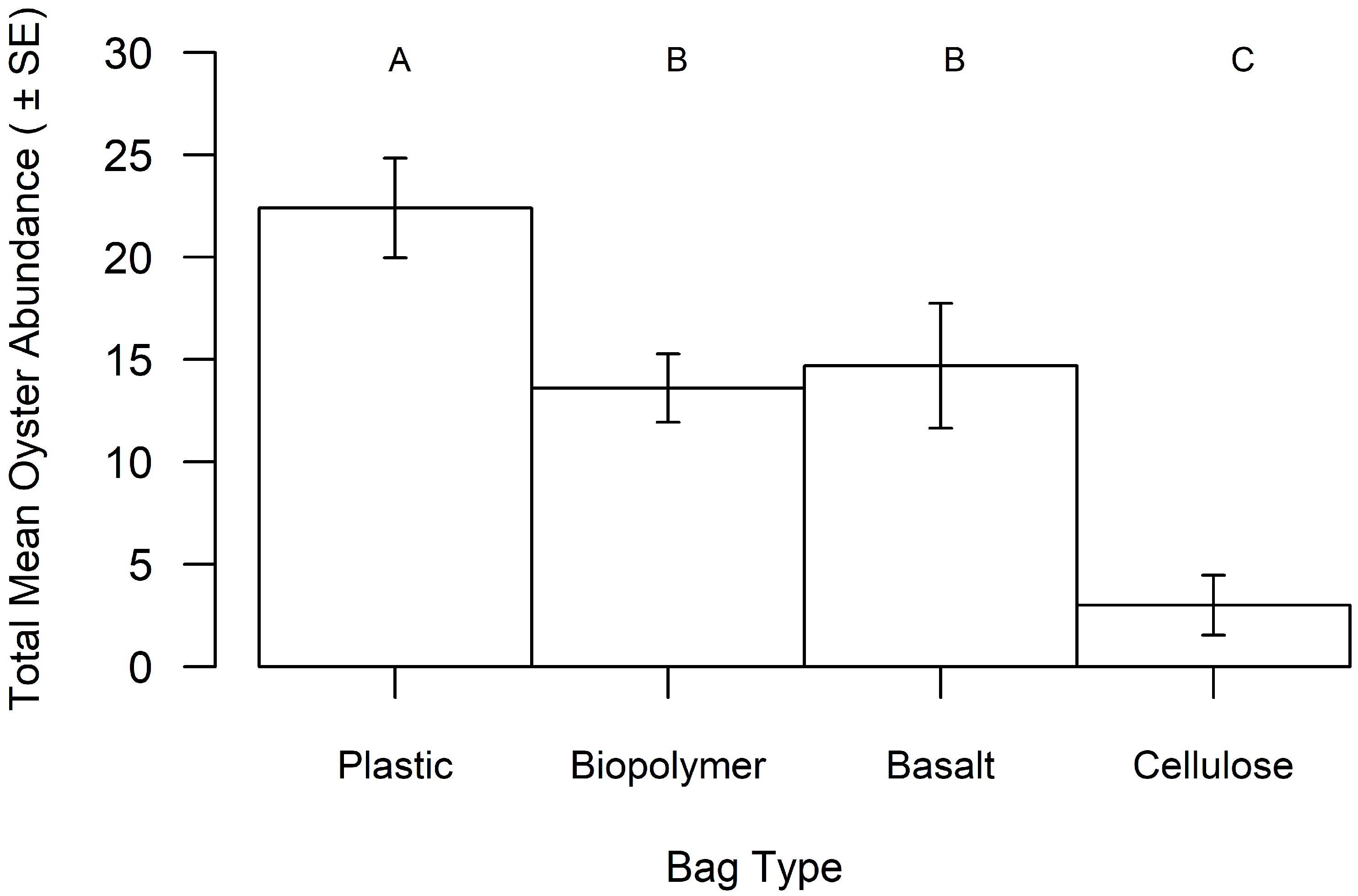

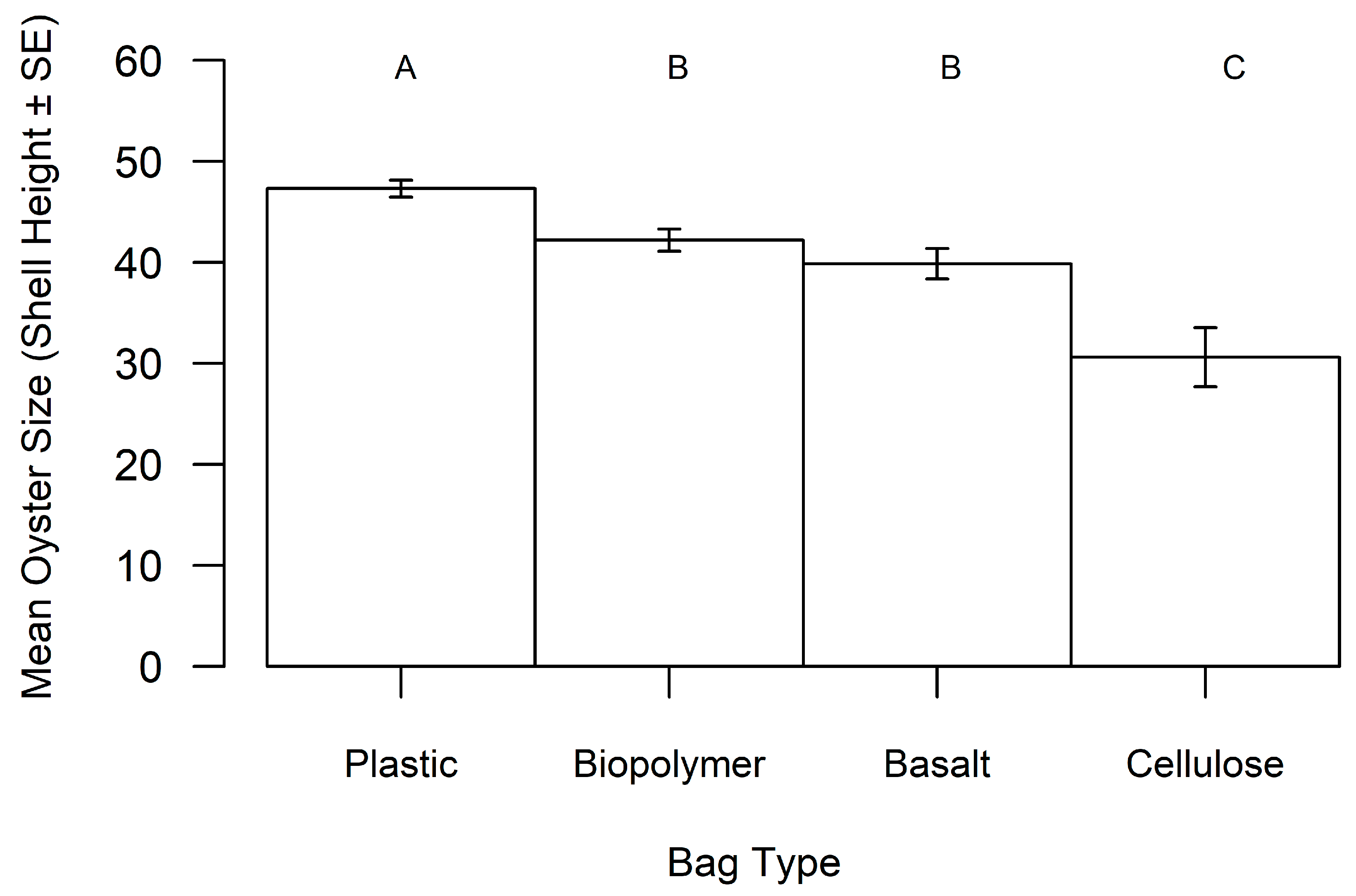

| Bag Material | Total Cost (in USD) 1 | Percent of Bags Retrieved | Mean Oyster Size (in mm) | Mean Oyster Abundance | Bag Preference Score 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plastic | 689.78 | 100% | 47.32 | 22.44 | 3.7 |

| Biopolymer | 683.74 | 76% | 42.20 | 13.37 | 9.4 |

| Basalt | 1010.97 | 56% | 39.87 | 14.71 | 177.8 |

| Cellulose | 793.15 | 36% | 30.66 | 4.22 | 495.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hanke, M.H.; Batte, S.; Goebel, R.C. Balancing Durability and Sustainability: Field Performance of Plastic and Biodegradable Materials in Eastern Oyster Breakwater Reef Restoration. Environments 2026, 13, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010042

Hanke MH, Batte S, Goebel RC. Balancing Durability and Sustainability: Field Performance of Plastic and Biodegradable Materials in Eastern Oyster Breakwater Reef Restoration. Environments. 2026; 13(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleHanke, Marc H., Shannon Batte, and Rachel C. Goebel. 2026. "Balancing Durability and Sustainability: Field Performance of Plastic and Biodegradable Materials in Eastern Oyster Breakwater Reef Restoration" Environments 13, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010042

APA StyleHanke, M. H., Batte, S., & Goebel, R. C. (2026). Balancing Durability and Sustainability: Field Performance of Plastic and Biodegradable Materials in Eastern Oyster Breakwater Reef Restoration. Environments, 13(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010042