Ecological and Microbial Processes in Green Waste Co-Composting for Pathogen Control and Evaluation of Compost Quality Index (CQI) Toward Agricultural Biosafety

Abstract

1. Introduction

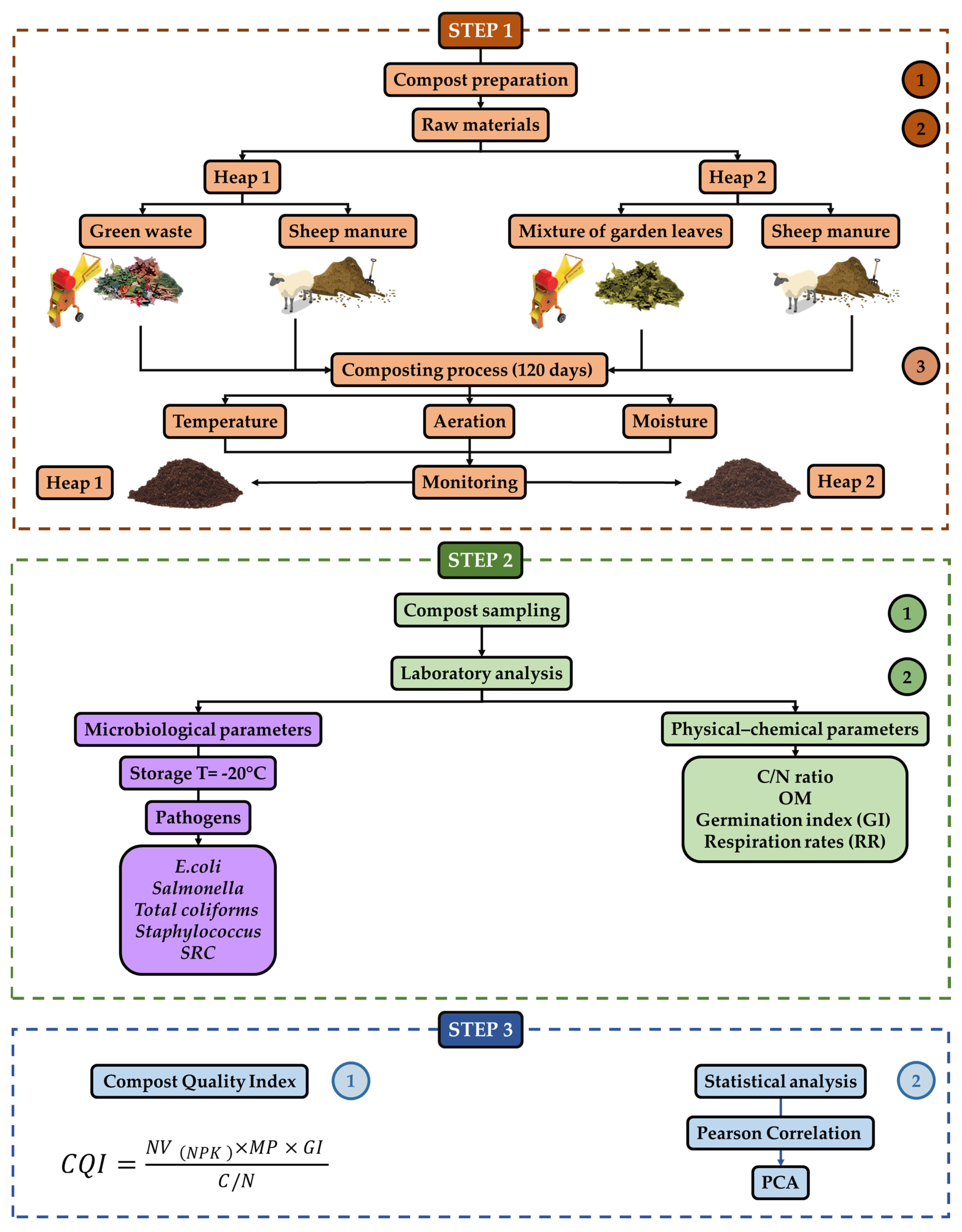

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Composting and Sampling Process

2.2. Microbial Analyses

2.2.1. Escherichia coli

2.2.2. Salmonella

2.2.3. Total Coliforms

2.2.4. Staphylococcus aureus

2.2.5. Sulfite-Reducing Clostridia

2.3. Compost Quality Index

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Compliance

3. Results and Discussion

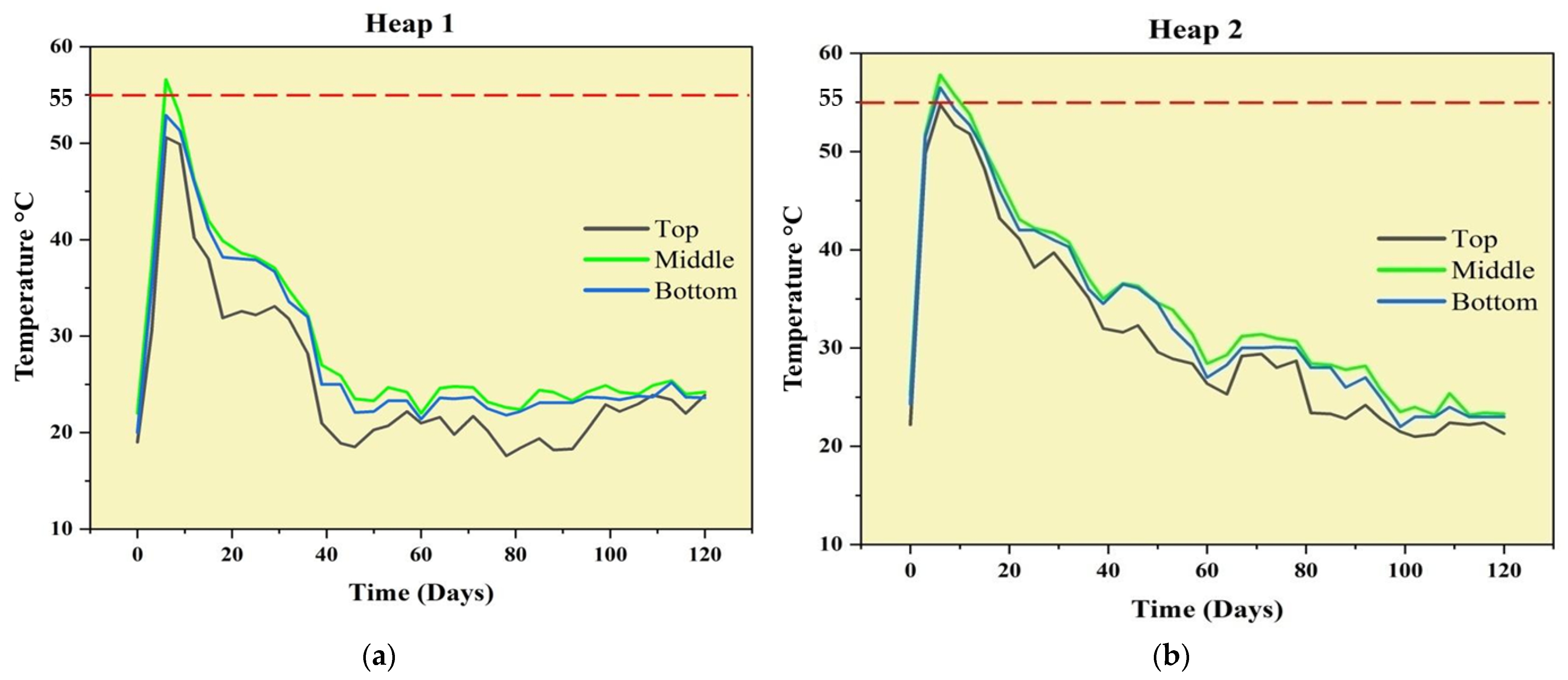

3.1. Temperature Monitoring and Pathogen Inactivation

3.2. Escherichia coli

3.3. Salmonella

3.4. Total Coliforms

3.5. Staphylococcus aureus

3.6. Sulfite-Reducing Clostridia

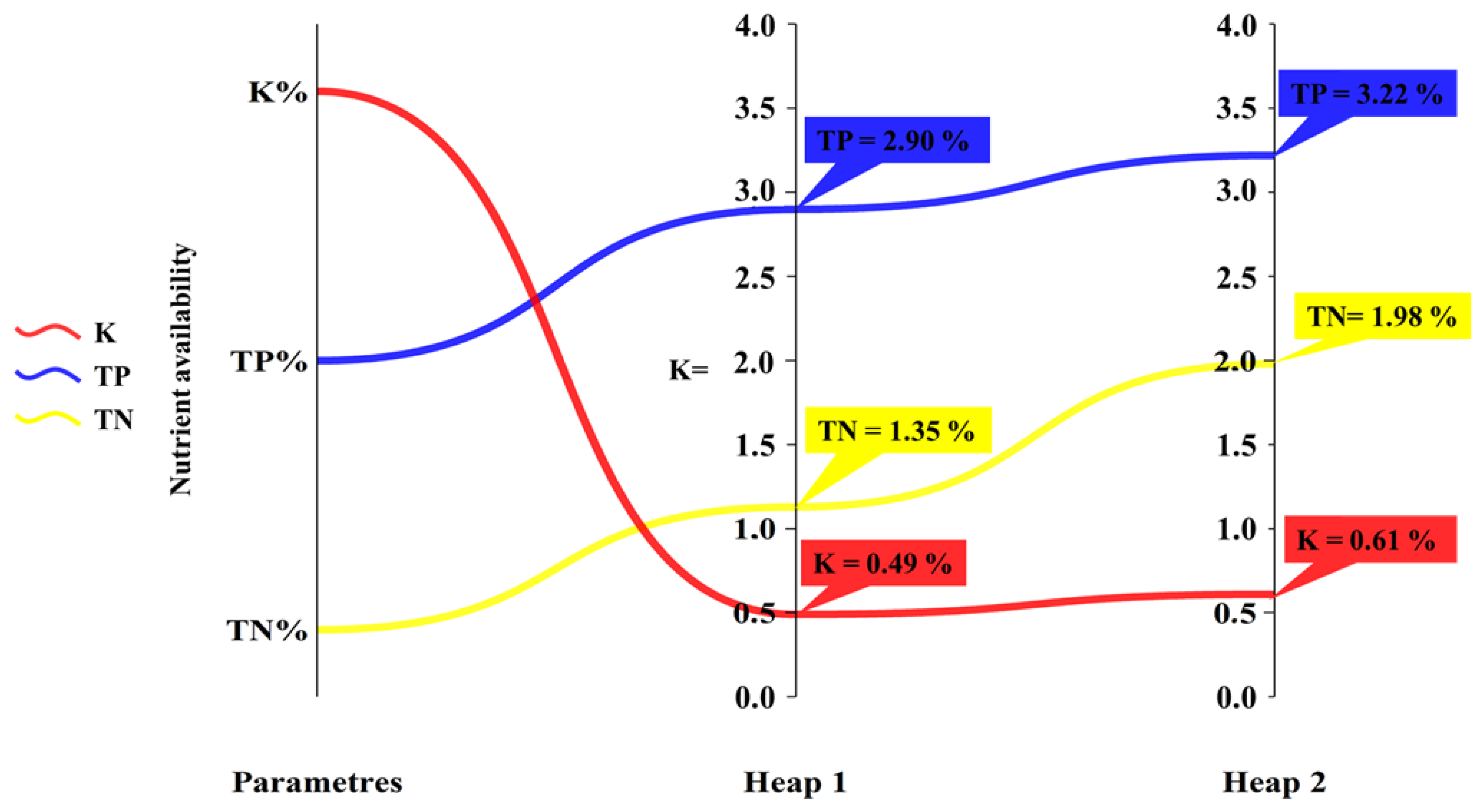

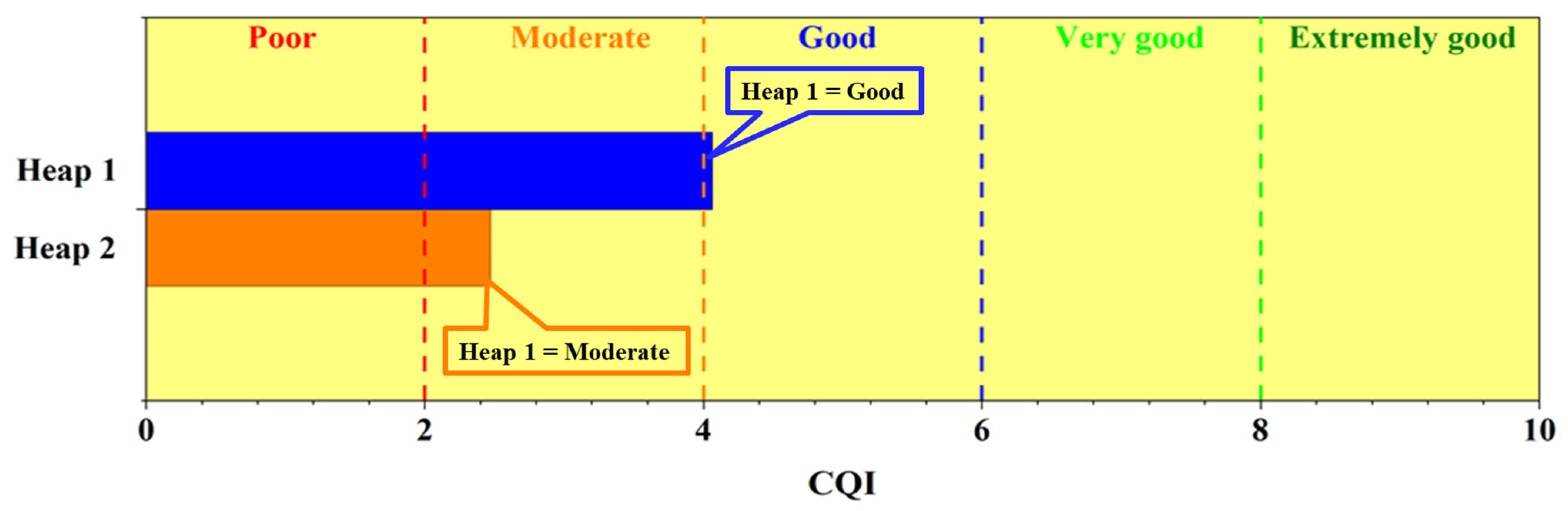

3.7. Compost Quality Index

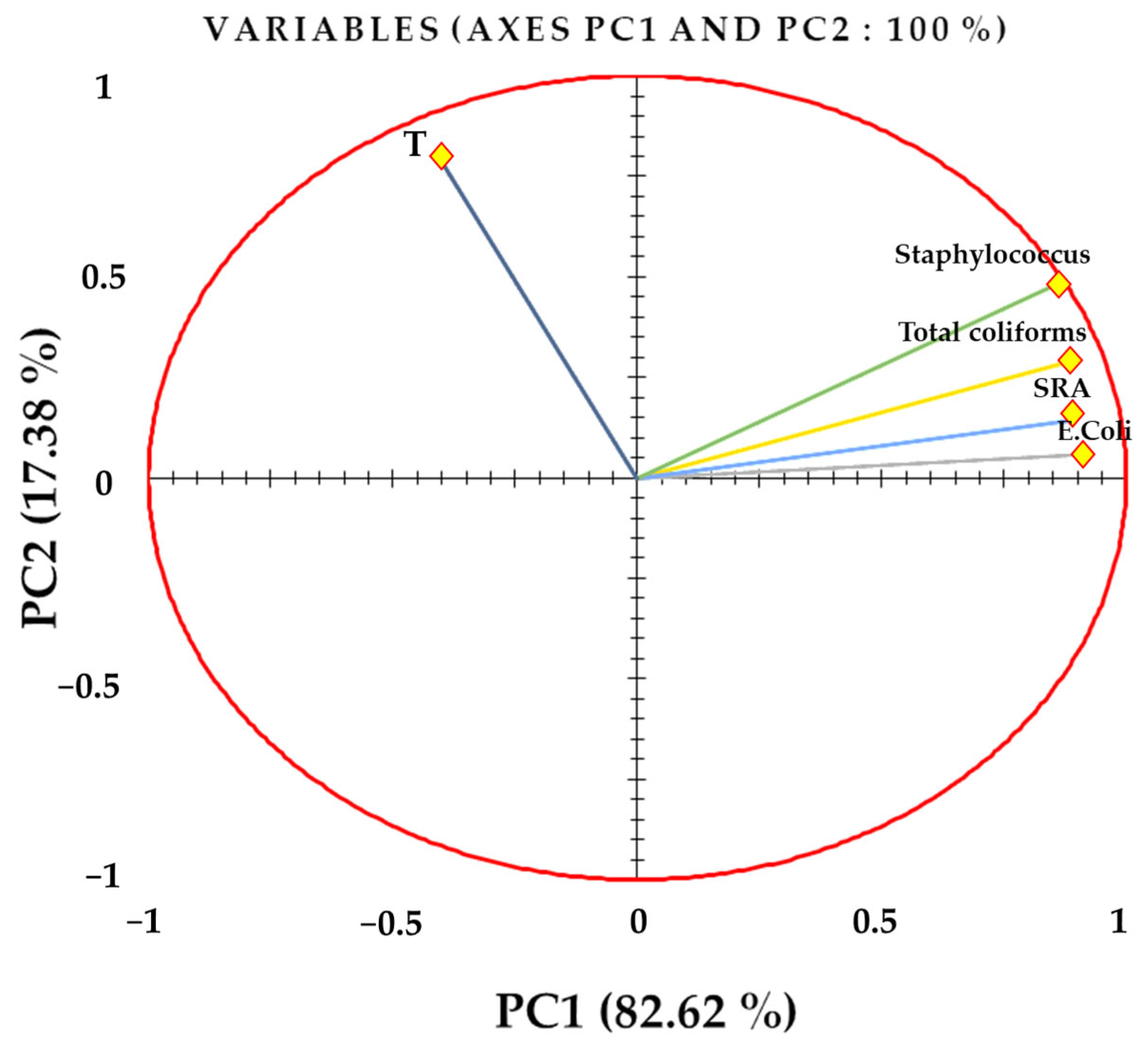

3.8. Statistical Analysis

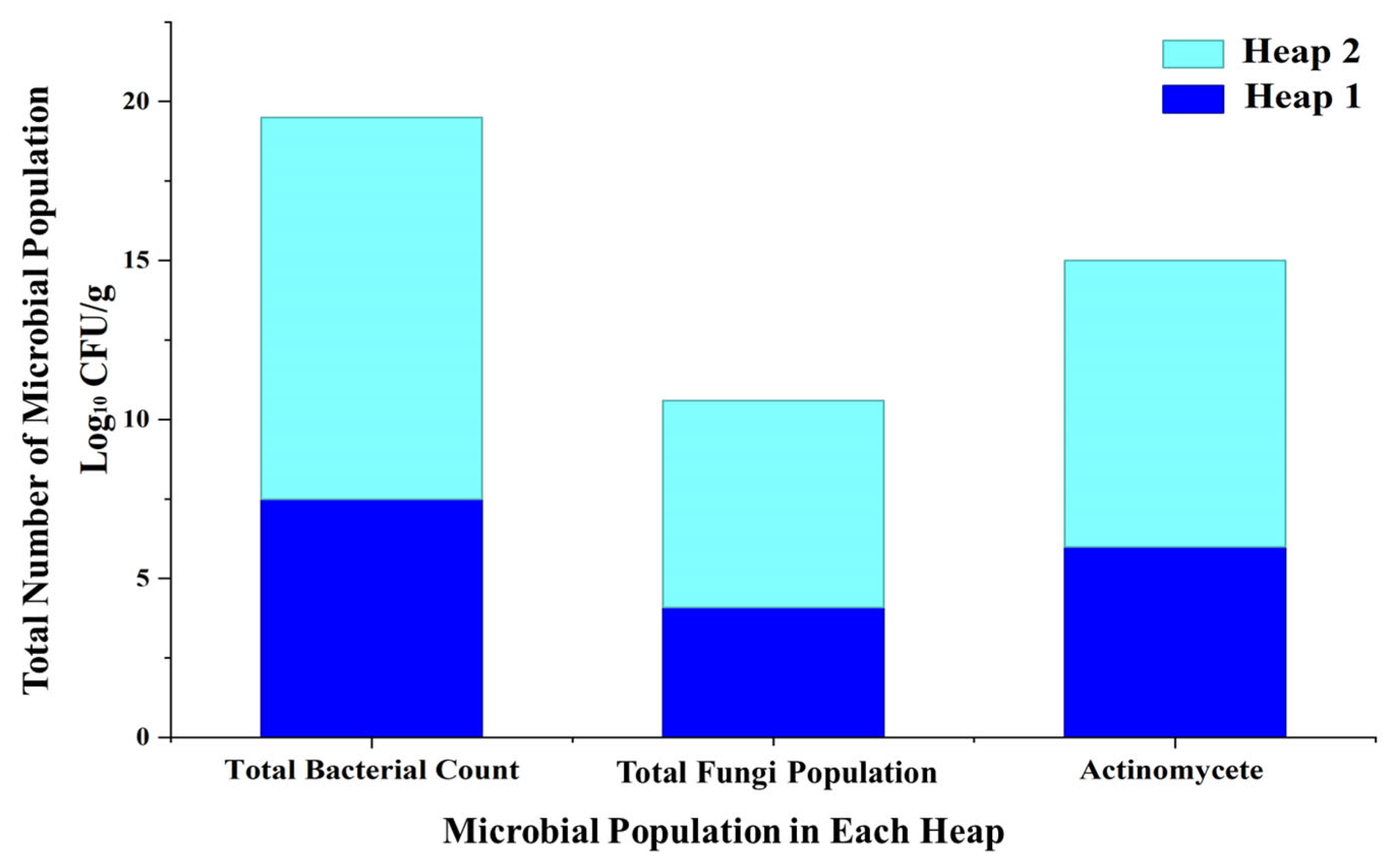

4. Assessment of Hygienization, Microbial Composition Changes, and Compost Quality Index

5. Ecological Risk Mitigation and Public Health Considerations

6. Implications for Circular Economy and Agricultural Sustainability and Organic Waste Valorization

7. Limitations of This Study and Future Recommendations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sortino, O.; Montoneri, E.; Patanè, C.; Rosato, R.; Tabasso, S.; Ginepro, M. Benefits for Agriculture and the Environment from Urban Waste. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 487, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oueld Lhaj, M.; Moussadek, R.; Zouahri, A.; Sanad, H.; Saafadi, L.; Mdarhri Alaoui, M.; Mouhir, L. Sustainable Agriculture Through Agricultural Waste Management: A Comprehensive Review of Composting’s Impact on Soil Health in Moroccan Agricultural Ecosystems. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboutayeb, R.; El-MriNi, S.; Zouhri, A.; IdriSsi, O.; AziM, K. Hygienization Assessment during Heap Co-Composting of Turkey Manure and Olive Mill Pomace. Eurasian J. Soil Sci. 2021, 10, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyon, L.; Burton, C.H.; Misselbrook, T.; Webb, J.; Philippe, F.X.; Aguilar, M.; Doreau, M.; Hassouna, M.; Veldkamp, T.; Dourmad, J.Y.; et al. Best Available Technology for European Livestock Farms: Availability, Effectiveness and Uptake. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 166, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oueld Lhaj, M.; Moussadek, R.; Mouhir, L.; Mdarhri Alaoui, M.; Sanad, H.; Iben Halima, O.; Zouahri, A. Assessing the Evolution of Stability and Maturity in Co-Composting Sheep Manure with Green Waste Using Physico-Chemical and Biological Properties and Statistical Analyses: A Case Study of Botanique Garden in Rabat, Morocco. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanad, H.; Moussadek, R.; Mouhir, L.; Oueld Lhaj, M.; Dakak, H.; El Azhari, H.; Yachou, H.; Ghanimi, A.; Zouahri, A. Assessment of Soil Spatial Variability in Agricultural Ecosystems Using Multivariate Analysis, Soil Quality Index (SQI), and Geostatistical Approach: A Case Study of the Mnasra Region, Gharb Plain, Morocco. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldan, E.; Nedeff, V.; Barsan, N.; Culea, M.; Panainte-Lehadus, M.; Mosnegutu, E.; Tomozei, C.; Chitimus, D.; Irimia, O. Assessment of Manure Compost Used as Soil Amendment—A Review. Processes 2023, 11, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Cai, R.; Luo, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yu, W.; Yang, Z. Reducing Moisture Content Can Promote the Removal of Pathogenic Bacteria and Viruses from Sheep Manure Compost on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nartey, E.G.; Sakrabani, R.; Tyrrel, S.; Cofie, O. Assessing Consistency in the Aerobic Co-Composting of Faecal Sludge and Food Waste in a Municipality in Ghana. Environ. Syst. Res. 2023, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, K.A.; Castro-Herrera, D.; Yimer, F.; Tadesse, M.; Kim, D.-G.; Prost, K.; Brüggemann, N.; Grohmann, E. Microbial Risk Assessment of Mature Compost from Human Excreta, Cattle Manure, Organic Waste, and Biochar. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Wang, J. Biological Control of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in Dairy Manure-Based Compost Using Competitive Exclusion Microorganisms. Pathogens 2024, 13, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Hashim, S.; Humphries, U.W.; Ahmad, S.; Noor, R.; Shoaib, M.; Naseem, A.; Hlaing, P.T.; Lin, H.A. Composting Processes for Agricultural Waste Management: A Comprehensive Review. Processes 2023, 11, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Xin, Y.; Wang, D.; Yuan, Q. Pyrolysis Characteristics of Cattle Manures Using a Discrete Distributed Activation Energy Model. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 172, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Brandón, M.; Lazcano, C.; Domínguez, J. The Evaluation of Stability and Maturity during the Composting of Cattle Manure. Chemosphere 2008, 70, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanad, H.; Moussadek, R.; Dakak, H.; Zouahri, A.; Oueld Lhaj, M.; Mouhir, L. Ecological and Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Groundwater within an Agricultural Ecosystem Using GIS and Multivariate Statistical Analysis (MSA): A Case Study of the Mnasra Region, Gharb Plain, Morocco. Water 2024, 16, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanad, H.; Mouhir, L.; Zouahri, A.; Moussadek, R.; El Azhari, H.; Yachou, H.; Ghanimi, A.; Oueld Lhaj, M.; Dakak, H. Assessment of Groundwater Quality Using the Pollution Index of Groundwater (PIG), Nitrate Pollution Index (NPI), Water Quality Index (WQI), Multivariate Statistical Analysis (MSA), and GIS Approaches: A Case Study of the Mnasra Region, Gharb Plain, Morocco. Water 2024, 16, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhou, K.; Moussadek, R.; Yachou, H.; Zouahri, A.; Douaik, A.; Hilal, I.; Ghanimi, A.; Hmouni, D.; Dakak, H. Assessing the Impact of Saline Irrigation Water on Durum Wheat (Cv. Faraj) Grown on Sandy and Clay Soils. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhou, K.; Mouna, T.; Moussadek, R.; Zouahri, A.; Ghanimi, A.; Sanad, H.; Lhaj, M.O.; Hmouni, D.; Dakak, H. Genetic Diversity and Performance of Durum Wheat (Triticum turgidum L. Ssp. Durum Desf.) Germplasm Based on Agro-Morphological and Quality Traits: Experimentation and Statistical Analysis. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oueld Lhaj, M.; Moussadek, R.; Mouhir, L.; Sanad, H.; Manhou, K.; Iben Halima, O.; Yachou, H.; Zouahri, A.; Mdarhri Alaoui, M. Application of Compost as an Organic Amendment for Enhancing Soil Quality and Sweet Basil (Ocimum Basilicum L.) Growth: Agronomic and Ecotoxicological Evaluation. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viaene, J.; Van Lancker, J.; Vandecasteele, B.; Willekens, K.; Bijttebier, J.; Ruysschaert, G.; De Neve, S.; Reubens, B. Opportunities and Barriers to On-Farm Composting and Compost Application: A Case Study from Northwestern Europe. Waste Manag. 2016, 48, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, F.L.F.; Martins, M.F. Thermochemically-Driven Treatment Units for Fecal Matter Sanitation: A Review Addressed to the Underdeveloped World. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabañas-Vargas, D.; De Los Ríos Ibarra, E.; Mena-Salas, J.; Escalante-Réndiz, D.; Rojas-Herrera, R. Composting Used as a Low Cost Method for Pathogen Elimination in Sewage Sludge in Mérida, Mexico. Sustainability 2013, 5, 3150–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengistu, T.; Gebrekidan, H.; Kibret, K.; Woldetsadik, K.; Shimelis, B.; Yadav, H. Comparative Effectiveness of Different Composting Methods on the Stabilization, Maturation and Sanitization of Municipal Organic Solid Wastes and Dried Faecal Sludge Mixtures. Environ. Syst. Res. 2017, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manga, M.; Muoghalu, C.; Camargo-Valero, M.A.; Evans, B.E. Effect of Turning Frequency on the Survival of Fecal Indicator Microorganisms during Aerobic Composting of Fecal Sludge with Sawdust. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizwan, H.M.; Naveed, M.; Sajid, M.S.; Nazish, N.; Younus, M.; Raza, M.; Maqbool, M.; Khalil, M.H.; Fouad, D.; Ataya, F.S. Enhancing Agricultural Sustainability through Optimization of the Slaughterhouse Sludge Compost for Elimination of Parasites and Coliforms. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Kim, J.; Shepherd, M.W.; Luo, F.; Jiang, X. Determining Thermal Inactivation of Escherichia Coli O157:H7 in Fresh Compost by Simulating Early Phases of the Composting Process. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 4126–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, R.; Roberts, S.J. Eradication of Plant Pathogens and Nematodes during Composting: A Review. Plant Pathol. 2004, 53, 548–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanad, H.; Oueld Lhaj, M.; Zouahri, A.; Saafadi, L.; Dakak, H.; Mouhir, L. Groundwater Pollution by Nitrate and Salinization in Morocco: A Comprehensive Review. J. Water Health 2024, 22, 1756–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.N.; Parsai, T. A Comprehensive Review on the Decentralized Composting Systems for Household Biodegradable Waste Management. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manga, M.; Camargo-Valero, M.A.; Anthonj, C.; Evans, B.E. Fate of Faecal Pathogen Indicators during Faecal Sludge Composting with Different Bulking Agents in Tropical Climate. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2021, 232, 113670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boni, A.; Melucci, F.M.; Acciani, C.; Roma, R. Community Composting: A Multidisciplinary Evaluation of an Inclusive, Participative, and Eco-Friendly Approach to Biowaste Management. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2022, 6, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berset, F.C.D.; Stoll, S. Microplastic Contamination in Field-Side Composting in Geneva, Switzerland (CH). Microplastics 2024, 3, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iswahyudi, I.; Widodo, W.; Warkoyo, W.; Sutanto, A.; Garfansa, M.P.; Septia, E.D. Determination and Quantification of Microplastics in Compost. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2024, 34, e22184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, T.; Vergara, S.E.; Silver, W.L. Assessing the Climate Change Mitigation Potential from Food Waste Composting. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Douglas, P.; Hansell, A.L.; Simmonds, N.J.; Piel, F.B. Assessing the Health Risk of Living near Composting Facilities on Lung Health, Fungal and Bacterial Disease in Cystic Fibrosis: A UK CF Registry Study. Environ. Health 2022, 21, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubini, S.; Galletti, G.; Bolognesi, E.; Bonilauri, P.; Tamba, M.; Savini, F.; Serraino, A.; Giacometti, F. Comparative Evaluation of Most Probable Number and Direct Plating Methods for Enumeration of Escherichia coli in Ruditapes Philippinarum, and Effect on Classification of Production and Relaying Areas for Live Bivalve Molluscs. Food Control 2023, 154, 110005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Robertson, I.D.; Guo, A.; Aleri, J.W. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Resistance of Salmonella and the Enumeration of ESBL E. Coli in Dairy Farms in Hubei Province, China. Prev. Vet. Med. 2023, 212, 105822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooijman, K.A.; Pielaat, A.; Kuijpers, A.F.A. Validation of ENISO 6579-1-Microbiology of the Food Chain-Horizontal Method forthe Detection, Enumeration and Serotyping of Salmonella—Part 1 Detection of Salmonella spp. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 288, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soobhany, N. Preliminary Evaluation of Pathogenic Bacteria Loading on Organic Municipal Solid Waste Compost and Vermicompost. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 206, 763–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kureljušić, J.M.; Vesković Moračanin, S.M.; Đukić, D.A.; Mandić, L.; Đurović, V.; Kureljušić, B.I.; Stojanova, M.T. Comparative Study of Vermicomposting: Apple Pomace Alone and in Combination with Wheat Straw and Manure. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiquia, S.M.; Wan, H.C.; Tam, N.F.Y. Microbial Population Dynamics and Enzyme Activities During Composting. Compost Sci. Util. 2002, 10, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiquia, S.M. Microbiological Parameters as Indicators of Compost Maturity. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 99, 816–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandna, P.; Nain, L.; Singh, S.; Kuhad, R.C. Assessment of Bacterial Diversity during Composting of Agricultural Byproducts. BMC Microbiol. 2013, 13, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutsanedzie, F.; Ofori, V.; Diaba, K.S. Maturity and Safety of Compost Processed in HV and TW Composting Systems. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2015, 3, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, K.; Zhang, B.; Lye, L.M. Assessment of Microbial Communities and Their Relationship with Enzymatic Activity during Composting. World J. Eng. Technol. 2017, 5, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta, G.; García-de-la-Fuente, R.; Abad, M.; Fornes, F. Isolation and Identification of Actinomycetes from a Compost-Amended Soil with Potential as Biocontrol Agents. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 95, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, R.; Datta, A.; Bose, S.; Dolui, A.K.; Chatterjee, A.; Dey, G.C.; Barik, A.; Sarkar, R.; Mazumdar, D.; Seal, A. Comparative Evaluation of Compost Quality, Process Convenience and Cost under Different Composting Methods to Assess Their Large Scale Adoptability Potential as Also Complemented by Compost Quality Index. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2013, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bedolla-Rivera, H.I.; Conde-Barajas, E.; Galván-Díaz, S.L.; Gámez-Vázquez, F.P.; Álvarez-Bernal, D.; de la Luz Xochilt Negrete-Rodríguez, M. Compost Quality Indexes (CQIs) of Biosolids Using Physicochemical, Biological and Ecophysiological Indicators: C and N Mineralization Dynamics. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manu, M.K.; Kumar, R.; Garg, A. Decentralized Composting of Household Wet Biodegradable Waste in Plastic Drums: Effect of Waste Turning, Microbial Inoculum and Bulking Agent on Product Quality. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan Topal, E.I.; Ünlü, A.; Topal, M. Effect of Aeration Rate on Elimination of Coliforms during Composting of Vegetable–Fruit Wastes. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2016, 5, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboutayeb, R.; Elgharous, M.; Abail, Z.; Elhari, M.; Koulali, Y. Stabilization and Sanitation of Chicken Litter by Heap Composting. Int. J. Eng. Res. 2013, 2, 124–139. [Google Scholar]

- Asses, N.; Farhat, W.; Hamdi, M.; Bouallagui, H. Large Scale Composting of Poultry Slaughterhouse Processing Waste: Microbial Removal and Agricultural Biofertilizer Application. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2019, 124, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanad, H.; Moussadek, R.; Mouhir, L.; Lhaj, M.O.; Zahidi, K.; Dakak, H.; Manhou, K.; Zouahri, A. Ecological and Human Health Hazards Evaluation of Toxic Metal Contamination in Agricultural Lands Using Multi-Index and Geostatistical Techniques across the Mnasra Area of Morocco’s Gharb Plain Region. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 18, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soobhany, N.; Mohee, R.; Garg, V.K. Inactivation of Bacterial Pathogenic Load in Compost against Vermicompost of Organic Solid Waste Aiming to Achieve Sanitation Goals: A Review. Waste Manag. 2017, 64, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odey, E.A.; Li, Z. Optimization of Integrated Compost-Dewatering and Pyrolysis for Sustainable Faecal Sludge Management: Enhancing Pathogen Inactivation and Biochar Production. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 13171–13184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, F.; Shen, C. Survival Characteristics of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus Isolated from Sludge Compost under Heat and Drying Stress: Implications for Pathogen Inactivation during Composting. Environ. Int. 2025, 198, 109464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourcher, A.-M.; Morand, P.; Picard-Bonnaud, F.; Billaudel, S.; Monpoeho, S.; Federighi, M.; Ferré, V.; Moguedet, G. Decrease of Enteric Micro-Organisms from Rural Sewage Sludge during Their Composting in Straw Mixture. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 99, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manga, M.; Muoghalu, C.C.; Acheng, P.O. Inactivation of Faecal Pathogens during Faecal Sludge Composting: A Systematic Review. Environ. Technol. Rev. 2023, 12, 150–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboutayeb, R. Valorisation Des Fumiers de Volailles de Chair: Compostage, Épandage et Étude Des Effets Des Fumiers de Volailles et Leurs Composts Sur Les Propriétés Physicochimiques Du Sol Sous Cultures de Maïs Fourrager et de Menthe Verte. Ph.D. Thesis, University Hassan I, Settat, Morocco, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, A.; Tabashsum, Z.; Alvarado-Martinez, Z.; Scriba, A.; Sellers, G.; Kapadia, S.; Canagarajah, C.; Biswas, D. Ecological Distribution of Staphylococcus in Integrated Farms within Washington DC–Maryland. J. Food Saf. 2024, 44, e13123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, N.; Wan, J.; Jousset, A.; Jiang, G.; Wang, X.; Wei, Z.; Xu, Y.; Shen, Q. Exploring the Antibiotic Resistance Genes Removal Dynamics in Chicken Manure by Composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 410, 131309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Sun, P.; Liu, B.; Ahmed, I.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, B. Effect of Extending High-Temperature Duration on ARG Rebound in a Co-Composting Process for Organic Wastes. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainisalo, A.; Romantschuk, M.; Kontro, M.H. Evolution of Clostridia and Streptomycetes in Full-Scale Composting Facilities and Pilot Drums Equipped with on-Line Temperature Monitoring and Aeration. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 7975–7983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkmen, O. Isolation and Counting of Clostridium Perfringens. In Microbiological Analysis of Foods and Food Processing Environments; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 217–227. ISBN 978-0-323-91651-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante, M.A.; Moral, R.; Paredes, C.; Vargas-García, M.C.; Suárez-Estrella, F.; Moreno, J. Evolution of the Pathogen Content during Co-Composting of Winery and Distillery Wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 7299–7306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, J.; López-González, J.A.; Arcos-Nievas, M.A.; Suárez-Estrella, F.; Jurado, M.M.; Estrella-González, M.J.; López, M.J. Revisiting the Succession of Microbial Populations throughout Composting: A Matter of Thermotolerance. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 773, 145587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Yuan, Z. Improving Food Waste Composting Efficiency with Mature Compost Addition. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 349, 126830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Chang, R.; Ren, Z.; Meng, X.; Li, Y.; Gao, M. Mature Compost Promotes Biodegradable Plastic Degradation and Reduces Greenhouse Gas Emission during Food Waste Composting. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 172081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, K.A.; Poehlein, A.; Schneider, D.; El-Said, K.; Wöhrmann, M.; Linkert, I.; Hübner, T.; Brüggemann, N.; Prost, K.; Daniel, R.; et al. Thermophilic Composting of Human Feces: Development of Bacterial Community Composition and Antimicrobial Resistance Gene Pool. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 824–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S.; Devi, S.; Devi, D.; Arya, P.; Manorma, K.; Kesta, K.; Sharma, M.; Bishist, R.; Tomar, M. Microbial and Physico-Chemical Dynamics Associated with Chicken Feather Compost Preparation Vis-à-Vis Its Impact on the Growth Performance of Tomato Crop. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 54, 102885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, S.; Guo, X.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, B. Succession and Diversity of Microorganisms and Their Association with Physicochemical Properties during Green Waste Thermophilic Composting. Waste Manag. 2018, 73, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Yu, X.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Li, J. Effects of Compost as a Soil Amendment on Bacterial Community Diversity in Saline–Alkali Soil. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1253415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Lu, C.; Luo, J.; Gong, X.; Guo, D.; Ma, Y. Matured Compost Amendment Improves Compost Nutrient Content by Changing the Bacterial Community during the Composting of Chinese Herb Residues. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1146546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oviedo-Ocaña, E.R.; Soto-Paz, J.; Parra-Orobio, B.A.; Zafra, G.; Maeda, T.; Galezo-Suárez, A.C.; Diaz-Larotta, J.T.; Sanchez-Torres, V. Effect of Biochar Addition in Two Different Phases of the Co-Composting of Green Waste and Food Waste: An Analysis of the Process, Product Quality and Microbial Community. Waste Biomass Valorization 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, R.; Jia, L.; Wang, L.; Pan, C.; Zhang, R.; Wei, Z. Microbial Inoculants Reshape Structural Distribution of Complex Components of Humic Acid Based on Spectroscopy during Straw Waste Composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 359, 127472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Le, B.; Tan, C.; Dong, C.; Yao, X.; Hu, B. Fungi Play a Crucial Role in Sustaining Microbial Networks and Accelerating Organic Matter Mineralization and Humification during Thermophilic Phase of Composting. Environ. Res. 2024, 254, 119155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Paredes, A.; Valdés, G.; Araneda, N.; Valdebenito, E.; Hansen, F.; Nuti, M. Microbial Community in the Composting Process and Its Positive Impact on the Soil Biota in Sustainable Agriculture. Agronomy 2023, 13, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; He, J.; Zhou, Z.; Xia, L.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Chu, H.; Liu, W.; et al. Organic Amendments Enhance Soil Microbial Diversity, Microbial Functionality and Crop Yields: A Meta-Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 829, 154627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Yang, B.; Zhang, M.; Song, D.; Xu, X.; Ai, C.; Liang, G.; Zhou, W. Investigating the Effects of Organic Amendments on Soil Microbial Composition and Its Linkage to Soil Organic Carbon: A Global Meta-Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 894, 164899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Torres, M.; Oviedo-Ocaña, E.R.; Dominguez, I.; Komilis, D.; Sánchez, A. A Systematic Review on the Composting of Green Waste: Feedstock Quality and Optimization Strategies. Waste Manag. 2018, 77, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanad, H.; Moussadek, R.; Mouhir, L.; Lhaj, M.O.; Dakak, H.; Manhou, K.; Zouahri, A. Monte Carlo Simulation for Evaluating Spatial Dynamics of Toxic Metals and Potential Health Hazards in Sebou Basin Surface Water. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, P.; Diep, L.; Hofmann, P.; Tomei, J.; Campos, L.C.; Teh, T.-H.; Mulugetta, Y.; Milligan, B.; Lakhanpaul, M. Synergies and trade-offs between sanitation and the sustainable development goals. UCL Open Environ. 2021, 3, e016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akanmu, A.O.; Babalola, O.O.; Venturi, V.; Ayilara, M.S.; Adeleke, B.S.; Amoo, A.E.; Sobowale, A.A.; Fadiji, A.E.; Glick, B.R. Plant Disease Management: Leveraging on the Plant-Microbe-Soil Interface in the Biorational Use of Organic Amendments. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 700507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crovella, T.; Paiano, A.; Falciglia, P.P.; Lagioia, G.; Ingrao, C. Wastewater Recovery for Sustainable Agricultural Systems in the Circular Economy—A Systematic Literature Review of Life Cycle Assessments. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanad, H.; Moussadek, R.; Mouhir, L.; Lhaj, M.O.; Dakak, H.; Zouahri, A. Geospatial Analysis of Trace Metal Pollution and Ecological Risks in River Sediments from Agrochemical Sources in Morocco’s Sebou Basin. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahalagedara, A.S.N.W.; Gkogka, E.; Hammershøj, M. A Review on Spore-Forming Bacteria and Moulds Implicated in the Quality and Safety of Thermally Processed Acid Foods: Focusing on Their Heat Resistance. Food Control 2024, 166, 110716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remize, F.; Santis, A.D. Chapter 7—Spore-Forming Bacteria. In The Microbiological Quality of Food, 2nd ed.; Bevilacqua, A., Corbo, M.R., Sinigaglia, M., Eds.; Woodhead Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Elsevier Science Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2025; pp. 157–174. ISBN 978-0-323-91160-3. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, G.; Kong, X.; Kang, J.; Su, N.; Luo, G.; Fei, J. Community-Level Dormancy Potential Regulates Bacterial Beta-Diversity Succession during the Co-Composting of Manure and Crop Residues. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 772, 145506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepesteur, M. Human and Livestock Pathogens and Their Control during Composting. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 52, 1639–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orser, C.S. Pre- and Post-Harvest Processing and Quality Standardization. In Revolutionizing the Potential of Hemp and Its Products in Changing the Global Economy; Belwal, T., Belwal, N.C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 197–219. ISBN 978-3-031-05144-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Lara, A.; Ros, M.; Cuartero, J.; Bustamante, M.Á.; Moral, R.; Andreu-Rodríguez, F.J.; Fernández, J.A.; Egea-Gilabert, C.; Pascual, J.A. Bacterial and Fungal Community Dynamics during Different Stages of Agro-Industrial Waste Composting and Its Relationship with Compost Suppressiveness. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 805, 150330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, N.; Zhang, J.; Hu, R.; Liu, S.; Liu, F.; Fan, Y.; Yang, H.; Huang, J.; Ding, J.; Chen, R.; et al. Hidden Pathogen Risk in Mature Compost: Low Optimal Growth Temperature Confers Pathogen Survival and Activity during Manure Composting. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 136230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelan, G.; Kim, K.; Pelton, M.A.; Soller, J.A.; Castleton, K.J.; Molina, M.; Pachepsky, Y.; Zepp, R. An Integrated Environmental Modeling Framework for Performing Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessments. Environ. Model. Softw. 2014, 55, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, A.; Dada, A.C.; Prajapati, S.K.; Arora, P. Integrating Life Cycle Assessment with Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment for a Holistic Evaluation of Sewage Treatment Plant. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 862, 160842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, R.; Russell, L.; Nolan, S.; Auer, A.; Markey, B.K.; Whyte, P.; O’Flaherty, V.; Bolton, D.; Fenton, O.; Richards, K.G.; et al. Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment Associated with Ready-to-Eat Salads Following the Application of Farmyard Manure and Slurry or Anaerobic Digestate to Arable Lands. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 151227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhou, K.; Taghouti, M.; Moussadek, R.; Elyacoubi, H.; Bennani, S.; Zouahri, A.; Ghanimi, A.; Sanad, H.; Oueld Lhaj, M.; Hmouni, D.; et al. Performance, Agro-Morphological, and Quality Traits of Durum Wheat (Triticum turgidum L. ssp. Durum Desf.) Germplasm: A Case Study in Jemâa Shaïm, Morocco. Plants 2025, 14, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortas, I.; Lal, R. Long-Term Fertilization Effect on Agronomic Yield and Soil Organic Carbon under Semi-Arid Mediterranean Region. J. Exp. Agric. Int. 2014, 4, 1086–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T. Effects of Compost on Soil Health and Greenhouse Gas Emissions: A Case Study in a Mediterranean Vineyard. Master’s Thesis, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bremaghani, A. Utilization of Organic Waste in Compost Fertilizer Production: Implications for Sustainable Agriculture and Nutrient Management. Law Econ. 2024, 18, 86–98. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, M.I.; Shahzad, K. Food Waste Recycling for Compost Production and Its Economic and Environmental Assessment as Circular Economy Indicators of Solid Waste Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 317, 128467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalalipour, H.; Binaee Haghighi, A.; Ferronato, N.; Bottausci, S.; Bonoli, A.; Nelles, M. Social, Economic and Environmental Benefits of Organic Waste Home Composting in Iran. Waste Manag. Res. 2025, 43, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnodifar, Z.; Ataei, P.; Karimi, H. Recycling Date Palm Waste for Compost Production: A Study of Sustainability Behavior of Date Palm Growers. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2023, 20, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senadheera, U.E.; Jayasanka, J.; Udayanga, D.; Hewawasam, C.; Amila, B.; Takimoto, Y.; Hatamoto, M.; Tadachika, N. Beyond Composting Basics: A Sustainable Development Goals—Oriented Strategic Guidance to IoT Integration for Composting in Modern Urban Ecosystems. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediyawa, H.N.S.D.; Munidasa, W.T.S. Diversity and Ecological Significance of Vermicomposting Bacteria. In Transformative Applied Research in Computing, Engineering, Science and Technology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; ISBN 978-1-003-61636-8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Fu, Y.; Wang, F.; Jin, P.; Xu, P.; Li, H.; Xu, X.; Shen, C. The Risk of Viable but Non-Culturable (VBNC) Enterococci and Antibiotic Resistance Transmission during Simulated Municipal Sludge Composting. Waste Manag. 2024, 183, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, D. Identifying Risks Associated with Organic Soil Amendments: Microbial Contamination in Compost and Manure Amendments. Biol. Forum–Int. J. 2021, 120, 275–379. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Noor, S.; Huan, R.; Liu, C.; Li, J.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Wu, C.; He, H. Comparison of the Diversity of Cultured and Total Bacterial Communities in Marine Sediment Using Culture-Dependent and Sequencing Methods. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sadi, A.M.; Al-Mazroui, S.S.; Phillips, A.J.L. Evaluation of Culture-based Techniques and 454 Pyrosequencing for the Analysis of Fungal Diversity in Potting Media and Organic Fertilizers. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 119, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidriales-Escobar, G.; Rentería-Tamayo, R.; Alatriste-Mondragón, F.; González-Ortega, O. Mathematical Modeling of a Composting Process in a Small-Scale Tubular Bioreactor. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2017, 120, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walling, E.; Trémier, A.; Vaneeckhaute, C. A Review of Mathematical Models for Composting. Waste Manag. 2020, 113, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.C.; Then, Y.L.; Hwang, S.S.; Tam, Y.C.; Chua, C.C.N. Modelling Temperature Profiles in Food Waste Composting: Monod Kinetics Under Varied Aeration Conditions. Process Integr. Optim. Sustain. 2025, 9, 839–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Muhayodin, F.; Larsen, O.C.; Miao, H.; Xue, B.; Rotter, V.S. A Review of Composting Process Models of Organic Solid Waste with a Focus on the Fates of C, N, P, and K. Processes 2021, 9, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Heap | C/N | OM % | GI % | RR (mg/g) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Final | Initial | Final | Final | Initial | Final | |

| Heap 1 | 28.68 | 12.49 | 24.85 | 29.00 | 86.93 | 0.45 | 6.00 |

| Heap 2 | 55.39 | 16.15 | 83.00 | 55.00 | 94.20 | 0.66 | 5.80 |

| CQI Values | Categories |

| CQI < 2 | Poor |

| 2 < CQI < 4 | Moderate |

| 4 < CQI < 6 | Good |

| 6 < CQI < 8 | Very good |

| 8 < CQI < 10 | Extremely good |

| Time | E. coli (CFU/g) | Total Coliforms (MNP/g) | SRC (CFU/g) | Staphylococcus (CFU/g) | Salmonella (CFU/g) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heap 1 | Heap 2 | Heap 1 | Heap 2 | Heap 1 | Heap 2 | Heap 1 | Heap 2 | Heap 1 | Heap 2 | |

| T0 | 3.0 × 104 | 3.1 × 104 | 6.7 × 107 | 6.8 × 107 | 3.9 × 104 | 4.8 × 104 | 4.4 × 105 | 3.9 × 105 | ND | ND |

| T 30 | 1.2 × 102 | 2.0 × 102 | 4.8 × 104 | 5.2 × 104 | 2.9 × 103 | 3.5 × 102 | 3.9 × 103 | 2.9 × 102 | ND | ND |

| T 60 | 1.0 × 102 | 1.0 × 102 | 6.0 × 102 | 4.9 × 103 | 1.2 × 102 | 1.0 × 102 | 2.3 × 102 | 1.1 × 102 | ND | ND |

| T 90 | <30 | <10 | 1.3 × 102 | 1.0 × 102 | <102 | <102 | 60 | <10 | ND | ND |

| T 120 | <10 | ND | 50 | 40 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | ND | ND |

| Variables | E. Coli | Total Coliforms | SRC | Staphylococcus | T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. Coli | 1 | ||||

| Total coliforms | 1.000 | 1 | |||

| SRC | 0.998 | 0.997 | 1 | ||

| Staphylococcus | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 1 | |

| T | −0.340 | −0.343 | −0.277 | −0.336 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Oueld Lhaj, M.; Moussadek, R.; Sanad, H.; Manhou, K.; Oueld Lhaj, M.; Mdarhri Alaoui, M.; Zouahri, A.; Mouhir, L. Ecological and Microbial Processes in Green Waste Co-Composting for Pathogen Control and Evaluation of Compost Quality Index (CQI) Toward Agricultural Biosafety. Environments 2026, 13, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010043

Oueld Lhaj M, Moussadek R, Sanad H, Manhou K, Oueld Lhaj M, Mdarhri Alaoui M, Zouahri A, Mouhir L. Ecological and Microbial Processes in Green Waste Co-Composting for Pathogen Control and Evaluation of Compost Quality Index (CQI) Toward Agricultural Biosafety. Environments. 2026; 13(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleOueld Lhaj, Majda, Rachid Moussadek, Hatim Sanad, Khadija Manhou, M’hamed Oueld Lhaj, Meriem Mdarhri Alaoui, Abdelmjid Zouahri, and Latifa Mouhir. 2026. "Ecological and Microbial Processes in Green Waste Co-Composting for Pathogen Control and Evaluation of Compost Quality Index (CQI) Toward Agricultural Biosafety" Environments 13, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010043

APA StyleOueld Lhaj, M., Moussadek, R., Sanad, H., Manhou, K., Oueld Lhaj, M., Mdarhri Alaoui, M., Zouahri, A., & Mouhir, L. (2026). Ecological and Microbial Processes in Green Waste Co-Composting for Pathogen Control and Evaluation of Compost Quality Index (CQI) Toward Agricultural Biosafety. Environments, 13(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010043