Three Years Later: Landfill Proximity Alters Biomarker Dynamics in White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) Nestlings

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (I)

- Biomarker responses would vary significantly among years, reflecting changes in environmental pollutant exposure over time;

- (II)

- Extracellular (plasma) and intracellular (S9) fractions would exhibit distinct patterns reflecting their different biochemistry: plasma represents circulating, extracellular processes, whereas the S9 fraction contains intracellular enzymes and substrates. Due to different biomarker activity or concentration, availability, and cell regulation, analysing both fractions allows detection of complementary physiological responses;

- (III)

- We expected that the landfill would continue to impose detectable neurotoxic and oxidative challenges on nestlings, consistent with previous reports from partially remediated landfills, although evaluating long-term trends was beyond the scope of this dataset.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Field Work and Blood Sampling

2.3. Chemicals

2.4. Esterase Activity

2.5. Oxidative Stress Biomarkers

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zalasiewicz, J.; Waters, C.N.; Wolfe, A.P.; Barnosky, A.D.; Cearreta, A.; Edgeworth, M.; Ellis, E.C.; Fairchild, I.J.; Gradstein, F.M.; Grinevald, J.; et al. Making the Case for a Formal Anthropocene Epoch: An Analysis of Ongoing Critiques. Newsl. Strat. 2017, 50, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramankutty, N.; Graumlich, L.; Achard, F.; Alves, D.; Chhabra, A.; DeFries, R.S.; Foley, J.A.; Geist, H.; Houghton, R.A.; Goldewijk, K.K.; et al. Global Land-Cover Change: Recent Progress, Remaining Challenges; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 9–39. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman, D. Landfill Urbanism: Opportunistic Ecologies, Wasted Landscapes. Detritus 2020, 11, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noreen, Z. A Global Modification in Avifaunal Behavior by Use of Waste Disposal Sites (Waste Dumps/Rubbish Dumps): A Review Paper. Pure Appl. Biol. 2021, 10, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasley, J.C.; Olson, Z.H.; Selva, N.; DeVault, T.L. Ecological Functions of Vertebrate Scavenging; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 125–157. [Google Scholar]

- Iravanian, A.; O Ravari, S. Types of Contamination in Landfills and Effects on The Environment: A Review Study. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 614, 012083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheswa, N.; Gokul, A.; Obame-Nkoghe, J.; Dube, N. Arthropod Assemblages in Municipal Solid Waste Landfills: Decomposers or Hidden Hazards? Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2025, 21, 1186–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjedov, D.; Mikuška, A.; Velki, M. From Wetlands to Landfills: White Stork (Ciconia ciconia L., 1758) as a Reliable Bioindicator of Ecosystem Health. Arch. Ind. Hyg. Toxicol. 2025, 76, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catry, I.; Franco, A.M.A.; Acácio, M. Where Have All the Storks Gone? Impact of Landfill Use on White Stork Behaviour and Population Dynamics. Waterbirds 2025, 47, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, N.I.; Correia, R.A.; Silva, J.P.; Pacheco, C.; Catry, I.; Atkinson, P.W.; Gill, J.A.; Franco, A.M.A. Are White Storks Addicted to Junk Food? Impacts of Landfill Use on the Movement and Behaviour of Resident White Storks (Ciconia ciconia) from a Partially Migratory Population. Mov. Ecol. 2016, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arizaga, J.; Resano-Mayor, J.; Villanúa, D.; Alonso, D.; Barbarin, J.M.; Herrero, A.; Lekuona, J.M.; Rodríguez, R. Importance of Artificial Stopover Sites Through Avian Migration Flyways: A Landfill-Based Assessment with the White Stork Ciconia ciconia. Ibis 2018, 160, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Casa-Resino, I.; Hernández-Moreno, D.; Castellano, A.; Pérez-López, M.; Soler, F. Breeding near a Landfill May Influence Blood Metals (Cd, Pb, Hg, Fe, Zn) and Metalloids (Se, As) in White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) Nestlings. Ecotoxicology 2014, 23, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, G.; Gómez-Ramírez, P.; Espín, S.; Sánchez-Virosta, P.; Frías, Ó.; García-Fernández, A.J. Domestic Waste and Wastewaters as Potential Sources of Pharmaceuticals in Nestling White Storks (Ciconia ciconia). Antibiotics 2023, 12, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjedov, D.; Velki, M.; Toth, L.; Filipović Marijić, V.; Mikuška, T.; Jurinović, L.; Ečimović, S.; Turić, N.; Lončarić, Z.; Šariri, S.; et al. Heavy Metal(loid) Effect on Multi-Biomarker Responses in Apex Predator: Novel Assays in the Monitoring of White Stork Nestlings. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 324, 121398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjedov, D.; Velki, M.; Kovačić, L.S.; Begović, L.; Lešić, I.; Jurinović, L.; Mikuska, T.; Sudarić Bogojević, M.; Ečimović, S.; Mikuška, A. White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) Nestlings Affected by Agricultural Practices? Assessment of Integrated Biomarker Responses. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaverková, M.D.; Paleologos, E.K.; Goli, V.S.N.S.; Koda, E.; Mohammad, A.; Podlasek, A.; Winkler, J.; Jakimiuk, A.; Černý, M.; Singh, D.N. Environmental Impacts of Landfills: Perspectives on Bio-Monitoring. Environ. Geotech. 2025, 12, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Pampliega, J.; Ramiro, Y.; Herrera-Dueñas, A.; Martinez-Haro, M.; Hernández, J.M.; Aguirre, J.I.; Höfle, U. A Multidisciplinary Approach to the Evaluation of the Effects of Foraging on Landfills on White Stork Nestlings. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 775, 145197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Pampliega, J.; Herrera-Dueñas, A.; de la Puente, J.; Aguirre, J.I.; Camarero, P.; Höfle, U. Influence of Climatic Conditions on the Link between Oxidative Stress Balance and Landfill Utilisation as a Food Resource by White Storks. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 903, 166116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adami, M.A.; Bertellotti, M.; Agüero, M.L.; Frixione, M.G.; D’Amico, V.L. Assessing the Impact of Urban Landfills as Feeding Sites on Physiological Parameters of a Generalist Seabird Species. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 202, 116327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogorb, M.A.; Ganga, R.; Vilanova, E.; Soler, F. Plasma Phenylacetate and 1-Naphthyl acetate Hydrolyzing Activities of Wild Birds as Possible Non-Invasive Biomarkers of Exposure to Organophosphorus and Carbamate Insecticides. Toxicol. Lett. 2007, 168, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oropesa, A.-L.; Gravato, C.; Sánchez, S.; Soler, F. Characterization of Plasma Cholinesterase from the White stork (Ciconia ciconia) and Its in Vitro Inhibition by Anticholinesterase Pesticides. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013, 97, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, L.G.; Hayes, J.D. Mechanisms of Induction of Cytosolic and Microsomal Glutathione Transferase (GST) Genes by Xenobiotics and Pro-Inflammatory Agents. Drug Metab. Rev. 2011, 43, 92–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, S.; Ganjayi, M.S.; Yellanurkonda, P.; Basha, S.; Meriga, B. Role of Glutathione S-Transferases in Detoxification of a Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon, Methylcholanthrene. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2018, 294, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, N.A.; Arukwe, A.; Jaspers, V.L.; Eulaers, I.; Mennilo, E.; Ibor, O.R.; Frantz, A.; Covaci, A.; Malik, R.N. Oxidative Stress Responses in Relationship to Persistent Organic Pollutant Levels in Feathers and Blood of Two Predatory Bird Species from Pakistan. Sci. Total. Environ. 2017, 580, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraguna, S.; Tur, S.M.; Sobočanec, S.; Pinterić, M.; Belić, M. Assessment of Oxidative Stress and Associated Biomarkers in Wild Avian Species. Animals 2025, 15, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikuška, A.; Alić, S.; Levak, I.; Bernal-Alviz, J.; Velki, M.; Nekić, R.; Ečimović, S.; Bjedov, D. Bayesian Structure Learning Reveals Disconnected Correlation Patterns Between Morphometric Traits and Blood Biomarkers in White Stork Nestlings. Birds 2025, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivula, M.J.; Eeva, T. Metal-Related Oxidative Stress in Birds. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 2359–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surai, P.F.; Kochish, I.I.; Fisinin, V.I.; Kidd, M.T. Antioxidant Defence Systems and Oxidative Stress in Poultry Biology: An Update. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjedov, D.; Mikuška, A.; Lackmann, C.; Begović, L.; Mikuška, T.; Velki, M. Application of Non-Destructive Methods: Biomarker Assays in Blood of White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) Nestlings. Animals 2021, 11, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barčić, D.; Ivančić, V. Impact of the Prudinec/Jakuševec Landfill on Environment Pollution. Sumar List. 2010, 137, 347–358. [Google Scholar]

- Nakić, Z.; Prce, M.; Posavec, K. Utjecaj Odlagališta Otpada Jakuševec-Prudinec Na Kakvoću Podzemne Vode. Rud. Zb. 2007, 19, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ahel, M.; Terzić, S.; Tepić, N. Organska Onečišćenja u Odlagalištu Otpada Jakuševec i Njihov Utjecaj Na Podzemne Vode. Arh Hig. Rada. Toksikol. 2006, 57, 307–315. [Google Scholar]

- Ellman, G.L.; Courtney, K.D.; Andres, V., Jr.; Featherstone, R.M. A New and Rapid Colorimetric Determination of Acetylcholinesterase Activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961, 7, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosokawa, M.; Satoh, T. Measurement of Carboxylesterase (CES) Activities. Curr. Protoc. Toxicol. 2001, 10, 4.7.1–4.7.14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habig, W.H.; Jakoby, W.B. Assays for Differentiation of Glutathione S-Transferases. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1981; pp. 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, Version 4.5.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Lenth, R.; Singmann, H.; Love, J.; Buerkner, P.; Herve, M. Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, Aka Least-Squares Means (Version 1.3.4). Emmeans Estim Marg Means Aka Least-Sq Means 2019, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Searle, S.R.; Speed, F.M.; Milliken, G.A. Population Marginal Means in the Linear Model: An Alternative to Least Squares Means. Am. Stat. 1980, 34, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiljević, R. Identifikacija Utjecaja Odlagališta Jakuševec—Prudinec Na Podzemne Vode Zagrebačkog Vodonosnika; University of Zagreb: Zagreb, Croatia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, D.M. Acetylcholinesterase: Enzyme Structure, Reaction Dynamics, and Virtual Transition States. Chem. Rev. 1987, 87, 955–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, P.; Wadkins, R. Carboxylesterases—Detoxifying Enzymes and Targets for Drug Therapy. Curr. Med. Chem. 2006, 13, 1045–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redinbo, M.R.; Potter, P.M. Mammalian Carboxylesterases: From Drug Targets to Protein Therapeutics. Drug Discov. Today 2005, 10, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morcillo, S.M.; Perego, M.C.; Vizuete, J.; Caloni, F.; Cortinovis, C.; Fidalgo, L.E.; López-Beceiro, A.; Míguez, M.P.; Soler, F.; Pérez-López, M. Reference Intervals for B-Esterases in gull, Larus michahellis (Nauman, 1840) from Northwest Spain: Influence of Age, Gender, and Tissue. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 1533–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Meharg, A.; Pain, D.J.; Ellam, R.M.; Baos, R.; Olive, V.; Joyson, A.; Powell, N.; Green, A.J.; Hiraldo, F. Isotopic Identification of the Sources of Lead Contamination for White Storks (Ciconia ciconia) in a Marshland Ecosystem (Doñana, S.W. Spain). Sci. Total. Environ. 2002, 300, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartkowiak, D.J.; Wilson, B.W. Avian Plasma Carboxylesterase Activity as a Potential Biomarker of Organophosphate Pesticide Exposure. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1995, 14, 2149–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oropesa, A.-L.; Gravato, C.; Guilhermino, L.; Soler, F. Antioxidant Defences and Lipid Peroxidation in Wild White Storks, Ciconia ciconia, from Spain. J. Ornithol. 2013, 154, 971–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gard, N.W.; Hooper, M.J. Age-Dependent Changes in Plasma and Brain Cholinesterase Activities of Eastern Bluebirds and European Starlings. J. Wildl. Dis. 1993, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, L.; Parent, A. The Monoamine-Containing Neurons in Avian Brain: I. A Study of the Brain Stem of the Chicken (Gallus domesticus) by Means of Fluorescence and Acetylcholinesterase Histochemistry. J. Comp. Neurol. 1981, 196, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.H. Acetylcholinesterase in the Hypothalamo-Hypophyseal Axis of the White-Crowned Sparrow, Zonotrichia leucophrys gambelii. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1968, 11, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, T.N.; Osofsky, A.; Jowett, P.L.H.; Hosgood, G. Acetylcholinesterase Concentrations in Heparinized Blood of Hispaniolan Amazon Parrots (Amazona ventralis). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2003, 34, 411–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westlake, G.E.; Bunyan, P.J.; Martin, A.D.; Stanley, P.I.; Steed, L.C. Carbamate Poisoning. Effects of Selected Carbamate Pesticides on Plasma Enzymes and Brain Esterases of Japanese Quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica). J. Agric. Food Chem. 1981, 29, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, C.S.A.; Monteiro, M.S.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Loureiro, S. Characterization of Cholinesterases in Plasma of Three Portuguese Native Bird Species: Application to Biomonitoring. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossi, M.C.; Leonzio, C.; Massi, A.; Lari, L.; Casini, S. Serum Esterase Inhibition in Birds: A Nondestructive Biomarker to Assess Organophosphorus and Carbamate Contamination. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1992, 23, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corson, M.S.; A Mora, M.; E Grant, W. Simulating Cholinesterase Inhibition in Birds Caused by Dietary Insecticide Exposure. Ecol. Model. 1998, 105, 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, C.; Sturve, J.; Almroth, B.; Andersson, S. The Impact of Urban Environment on Oxidative Damage (TBARS) and Antioxidant Systems in Lungs and Liver of Great Tits, Parus major. Environ. Res. 2009, 109, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaver, M.; George, S. A Piscine Glutathione S-Transferase Which Efficiently Conjugates the End-Products of Lipid Peroxidation. Mar. Environ. Res. 1998, 46, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.D.; Pulford, D.J. The Glutathione S-Transferase Supergene Family: Regulation of GST and the Contribution of the lsoenzymes to Cancer Chemoprotection and Drug Resistance Part I. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1995, 30, 445–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijhoff, W.A.; Mulder, T.P.; Verhagen, H.; van Poppel, G.; Peters, W.H. Effects of Consumption of Brussels Sprouts on Plasma and Urinary Glutathione S-Transferase Class-α and -π in Humans. Carcinog. 1995, 16, 955–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, N.A.; Eulaers, I.; Jaspers, V.L.B.; Pauw, J. Oxidative Stress Responses in Relationship to Persistent Organic Pollutant Levels in Feathers and Blood of Two Predatory Bird Species from Pakistan. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 231, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Virosta, P.; Espín, S.; Ruiz, S.; Panda, B.; Ilmonen, P.; Schultz, S.L.; Karouna-Renier, N.; García-Fernández, A.J.; Eeva, T. Arsenic-Related Oxidative Stress in Experimentally-Dosed Wild Great Tit Nestlings. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 259, 113813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berglund, Å.; Sturve, J.; Förlin, L.; Nyholm, N. Oxidative Stress in Pied Flycatcher (Ficedula hypoleuca) Nestlings from Metal Contaminated Environments in Northern Sweden. Environ. Res. 2007, 105, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, Å.M.M.; Rainio, M.J.; Kanerva, M.; Nikinmaa, M.; Eeva, T. Antioxidant Status in Relation to Age, Condition, Reproductive Performance and Pollution in Three Passerine Species. J. Avian Biol. 2014, 45, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Casa-Resino, I.; Hernández-Moreno, D.; Castellano, A.; Soler Rodríguez, F.; Pérez-López, M. Biomarkers of oxidative status associated with metal pollution in the blood of the white stork (Ciconia ciconia) in Spain. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2015, 97(5), 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espín, S.; Martínez-López, E.; León-Ortega, M.; Martínez, J.E.; García-Fernández, A.J. Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Eurasian Eagle Owls (Bubo bubo) in Three Different Scenarios of Heavy Metal Exposure. Environ. Res. 2014, 131, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D.J.; Spalding, M.G.; Frederick, P.C. Subchronic Effects of Methylmercury on Plasma and Organ Biochemistries in Great Egret Nestlings. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2005, 24, 3078–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espín, S.; Martínez-López, E.; Jiménez, P.; María-Mojica, P.; García-Fernández, A.J. Effects of Heavy Metals on Biomarkers for Oxidative Stress in Griffon Vulture (Gyps fulvus). Environ. Res. 2014, 129, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivula, M.J.; Kanerva, M.; Salminen, J.-P.; Nikinmaa, M.; Eeva, T. Metal Pollution Indirectly Increases Oxidative Stress in Great tit (Parus major) Nestlings. Environ. Res. 2011, 111, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainio, M.J.; Kanerva, M.; Salminen, J.-P.; Nikinmaa, M.; Eeva, T. Oxidative Status in Nestlings of Three Small Passerine Species Exposed to Metal Pollution. Sci. Total. Environ. 2013, 454–455, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiński, P.; Kurhalyuk, N.; Jerzak, L.; Kasprzak, M.; Tkachenko, H.; Klawe, J.J.; Szady-Grad, M.; Koim, B.; Wiśniewska, E. Ecophysiological Determinations of Antioxidant Enzymes and Lipoperoxidation in the Blood of White Stork Ciconia ciconia from Poland. Environ. Res. 2009, 109, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiński, P.; Kurhalyuk, N.; Kasprzak, M.; Jerzak, L.; Tkachenko, H.; Szady-Grad, M.; Klawe, J.J.; Koim, B. The Impact of Element–Element Interactions on Antioxidant Enzymatic Activity in the Blood of White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) Chicks. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2009, 56, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Rueda, G.; Redondo, T.; E Trenzado, C.; Sanz, A.; Zúñiga, J.M. Oxidative Stress Mediates Physiological Costs of Begging in Magpie (Pica pica) Nestlings. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko, H.; Kurhaluk, N. Blood Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Defense Profile of White Stork Ciconia ciconia Chicks Reflect the Degree of Environmental Pollution. Ecol. Quest. 2014, 18, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Upton, J.R.; Edens, F.W.; Ferket, P.R. The Effects of Dietary Oxidized Fat and Selenium Source on Performance, Glutathione Peroxidase, and Glutathione Reductase Activity in Broiler Chickens. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2009, 18, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Shafy, H.I.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Al-Sulaiman, A.M.; Okasha, R.A. Landfill Leachate: Sources, Nature, Organic Composition, and Treatment: An Environmental Overview. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Chardi, A.; Peñarroja-Matutano, C.; Borrás, M.; Nadal, J. Bioaccumulation of Metals and Effects of a Landfill in Small Mammals Part III: Structural Alterations. Environ. Res. 2009, 109, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Sang, N.; Guo, D. Oxidative Damage Induced in Hearts, Kidneys and Spleens of Mice by Landfill Leachate. Chemosphere 2006, 65, 1058–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimba, C.G.; Bakare, A.A.; Aina, O.O. Liver and Kidney Dysfunction in Wistar Rats Exposed to Municipal Landfill Leachate. Resour. Environ. 2012, 2, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farombi, E.O.; Akintunde, J.K.; Nzute, N.; Adedara, I.A.; Arojojoye, O. Municipal Landfill Leachate Induces Hepatotoxicity and Oxidative Stress in Rats. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2012, 28, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, J.; Alia, M.; Hernández, A.J.; Adarve, M.J.; Urcelay, A.; Antón, F.A. Ecotoxicological Studies on Effects of Landfill Leachates on Plants and Animals in Central Spain. Sci. Total. Environ. 1993, 134, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimba, C.G.; Bakare, A.A. In Vivo Micronucleus Test in the Assessment of Cytogenotoxicity of Landfill Leachates in Three Animal Models from Various Ecological Habitats. Ecotoxicology 2016, 25, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-García, A.; Sanz-Aguilar, A.; Aguirre, J.I. The Trade-Offs of Foraging at Landfills: Landfill Use Enhances Hatching Success but Decrease the Juvenile Survival of Their Offspring on White Storks (Ciconia ciconia). Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 778, 146217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Biomarker | Unit | Year | Fraction | n (individual) | n (nest) | Min | 25% | Median | 75% | Max | Range | Mean | SD | SE | CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AChE | (nmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 2025 | Plasma | 11 | 11 | 19.45 | 23.61 | 28.41 | 33.95 | 39.79 | 20.34 | 29.12 | 6.01 | 1.81 | 20.62% |

| CES | (nmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 2.63 | 3.07 | 3.98 | 5.18 | 6.41 | 3.78 | 4.13 | 1.24 | 0.37 | 30.03% | ||||

| GST | (nmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 4.97 | 5.16 | 6.53 | 9.01 | 12.21 | 7.24 | 7.47 | 2.34 | 0.71 | 31.31% | ||||

| GR | (pmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 27.74 | 49.58 | 65.32 | 106.24 | 118.12 | 90.38 | 74.26 | 32.25 | 9.72 | 43.43% | ||||

| ROS | (RFU) | 126 | 136 | 144 | 157 | 186 | 60 | 147 | 17.13 | 5.17 | 11.65% | ||||

| GSH | (RFU) | 5198 | 6936 | 7056 | 9602 | 9693 | 4495 | 7666 | 1524 | 459.6 | 19.89% | ||||

| AChE | (nmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | S9 | 0.61 | 0.69 | 0.76 | 0.88 | 1.08 | 0.47 | 0.78 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 16.46% | |||

| CES | (nmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 1.04 | 1.14 | 1.16 | 1.23 | 1.76 | 0.72 | 1.22 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 15.73% | ||||

| GST | (nmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 0.33 | 0.76 | 1.14 | 1.41 | 1.86 | 1.53 | 1.09 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 38.07% | ||||

| GR | (pmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 77.36 | 132.39 | 174.68 | 241.64 | 393.69 | 316.33 | 194.39 | 91.68 | 27.64 | 47.16% | ||||

| ROS | (RFU) | 70 | 75 | 89 | 133 | 304 | 234 | 111.60 | 67.86 | 20.46 | 60.79% | ||||

| GSH | (RFU) | 5497 | 10,429 | 13,859 | 16,256 | 16,409 | 10,912 | 12,957 | 3460 | 1043 | 26.70% | ||||

| AChE | (nmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 2022 | Plasma | 10 | 10 | 16.22 | 20.36 | 28.52 | 29.55 | 51.51 | 35.29 | 27.31 | 10.02 | 3.17 | 36.68% |

| CES | (nmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 10.22 | 23.00 | 28.68 | 45.99 | 62.77 | 52.55 | 32.89 | 16.43 | 5.20 | 49.95% | ||||

| GST | (nmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 9.87 | 11.13 | 11.94 | 15.82 | 17.22 | 7.35 | 13.17 | 2.64 | 0.83 | 20.01% | ||||

| GR | (pmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 141.47 | 200.60 | 273.86 | 331.96 | 364.71 | 223.24 | 266.29 | 79.16 | 25.03 | 29.73% | ||||

| ROS | (RFU) | 90 | 111 | 115.5 | 131 | 137 | 47 | 118.40 | 14.10 | 4.46 | 11.91% | ||||

| GSH | (RFU) | 2062 | 3601 | 3974 | 4731 | 6306 | 4244 | 4097 | 1116 | 353 | 27.24% | ||||

| AChE | (nmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | S9 | 3.29 | 3.66 | 4.14 | 6.44 | 7.00 | 3.71 | 4.76 | 1.42 | 0.45 | 29.93% | |||

| CES | (nmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 6.66 | 7.49 | 7.77 | 8.47 | 12.84 | 6.18 | 8.31 | 1.73 | 0.55 | 20.80% | ||||

| GST | (nmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 8.30 | 9.89 | 12.71 | 16.93 | 17.90 | 9.60 | 13.25 | 3.64 | 1.15 | 27.51% | ||||

| GR | (pmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 535.42 | 742.04 | 907.15 | 1055.89 | 1533.64 | 998.22 | 923.05 | 285.17 | 90.18 | 30.89% | ||||

| ROS | (RFU) | 27 | 37.25 | 48.5 | 65.5 | 81 | 54 | 52.20 | 16.77 | 5.30 | 32.12% | ||||

| GSH | (RFU) | 17,294 | 19,450 | 21,536 | 22,534 | 23,564 | 6270 | 21,066 | 1987 | 628 | 9.433% | ||||

| AChE | (nmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 2021 | Plasma | 8 | 8 | 20.39 | 21.14 | 23.45 | 27.83 | 30.57 | 10.18 | 24.36 | 3.73 | 1.32 | 15.31% |

| CES | (nmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 20.47 | 34.37 | 48.44 | 72.87 | 79.10 | 58.63 | 50.45 | 20.63 | 7.30 | 40.90% | ||||

| GST | (nmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 6.35 | 6.67 | 8.30 | 8.66 | 8.98 | 2.63 | 7.93 | 1.01 | 0.38 | 12.74% | ||||

| GR | (pmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 91.13 | 192.85 | 216.71 | 251.06 | 267.71 | 176.58 | 209.87 | 57.35 | 20.28 | 27.33% | ||||

| ROS | (RFU) | 84 | 90 | 104 | 123 | 126 | 42 | 105.30 | 16.77 | 5.93 | 15.94% | ||||

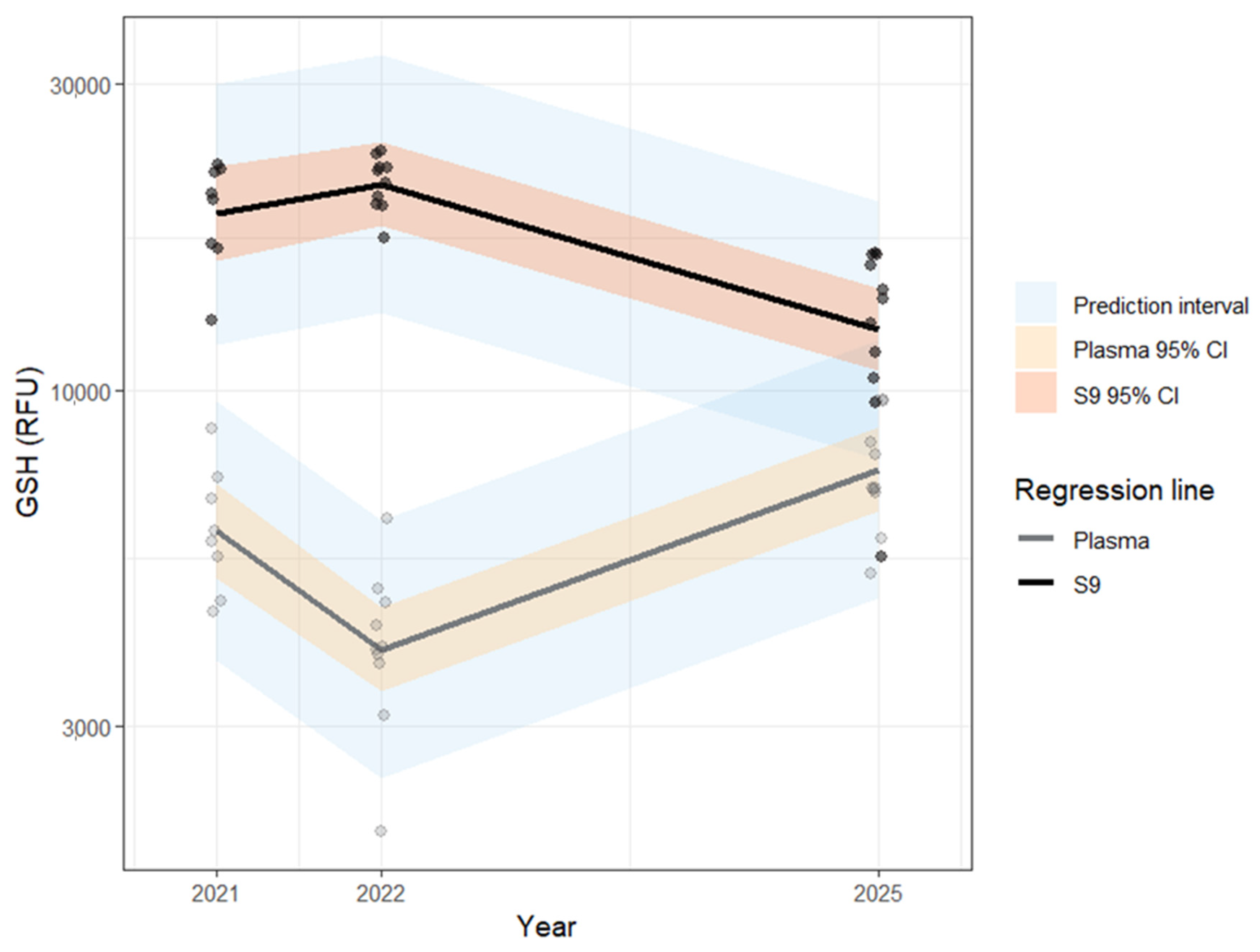

| GSH | (RFU) | 4535 | 4899 | 5938 | 7179 | 8741 | 4206 | 6180 | 1399 | 495 | 22.64% | ||||

| AChE | (nmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | S9 | 1.28 | 1.91 | 3.41 | 4.09 | 4.46 | 3.18 | 3.12 | 1.15 | 0.41 | 36.98% | |||

| CES | (nmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 2.05 | 2.34 | 3.17 | 5.49 | 6.31 | 4.26 | 3.92 | 1.72 | 0.65 | 44.01% | ||||

| GST | (nmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 18.98 | 20.05 | 23.80 | 45.20 | 54.42 | 35.44 | 30.63 | 13.93 | 4.93 | 45.48% | ||||

| GR | (pmol min−1 mgPROT−1) | 275.21 | 894.25 | 1235.13 | 1416.04 | 1711.37 | 1436.16 | 1130.33 | 451.59 | 159.66 | 39.95% | ||||

| ROS | RFU(RFU) | 25 | 31 | 48 | 67 | 73 | 48 | 48.25 | 18.03 | 6.37 | 37.37% | ||||

| GSH | (RFU) | 12,834 | 16,734 | 20,044 | 22,051 | 22,434 | 9600 | 19,122 | 3373 | 1193 | 17.64% |

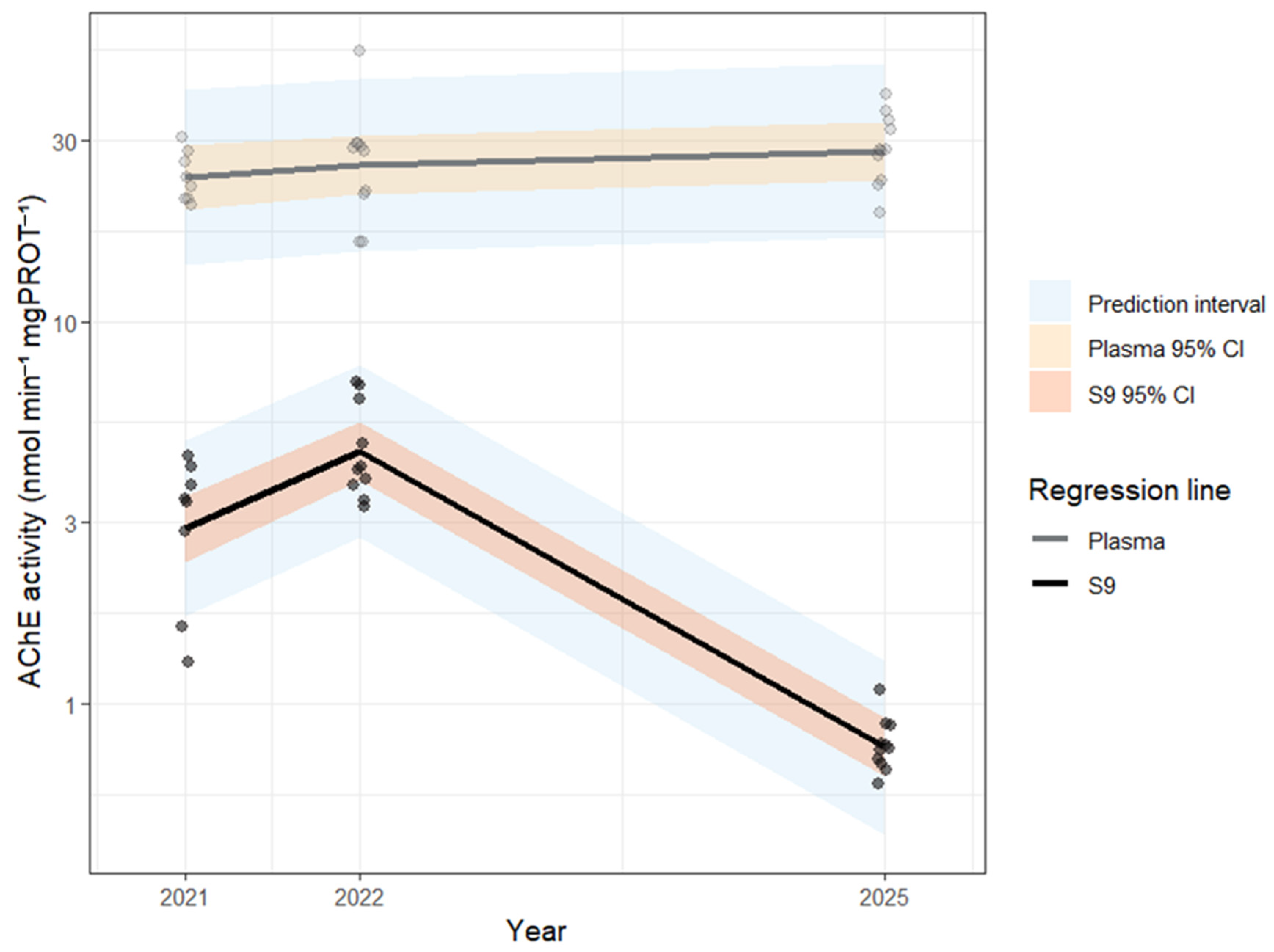

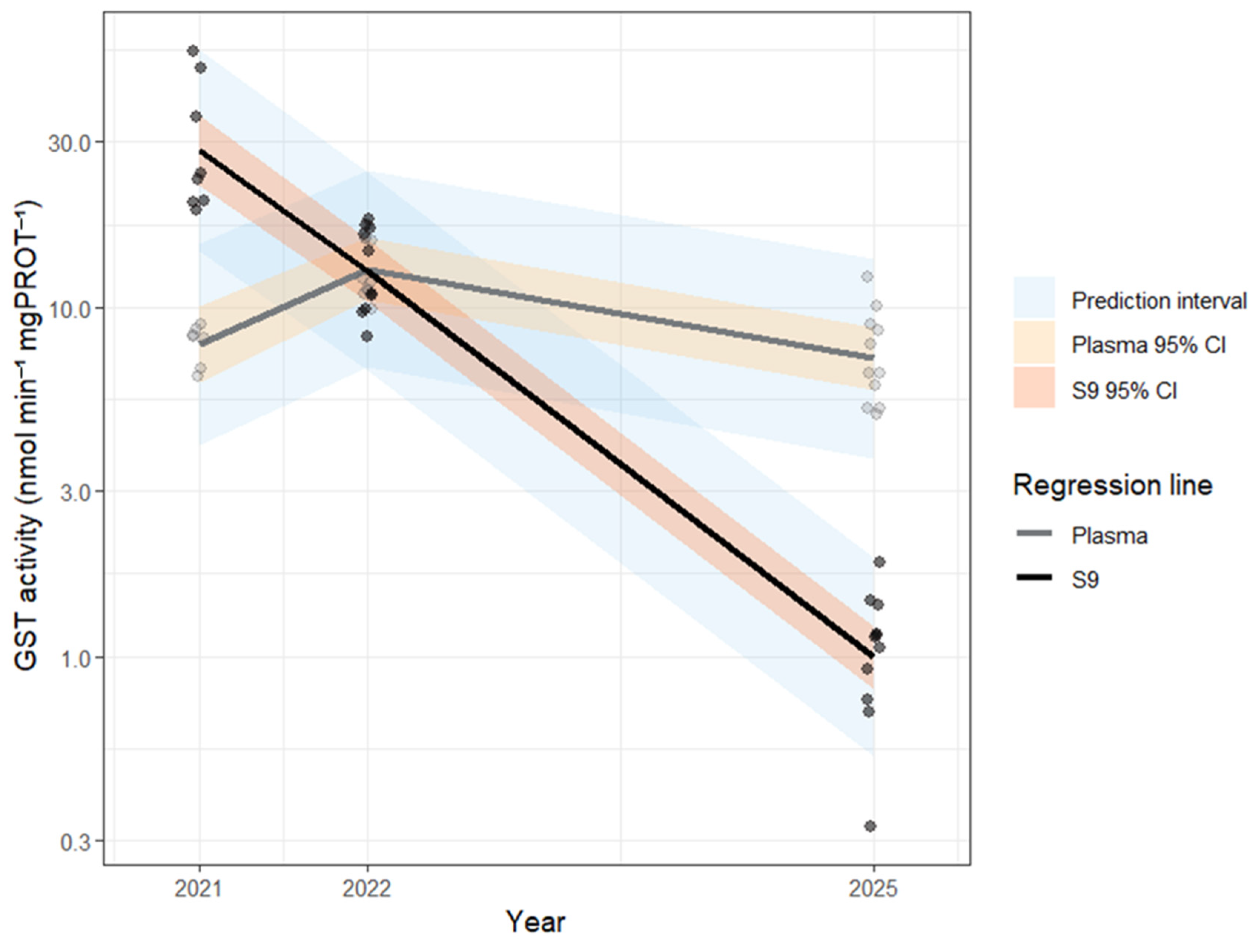

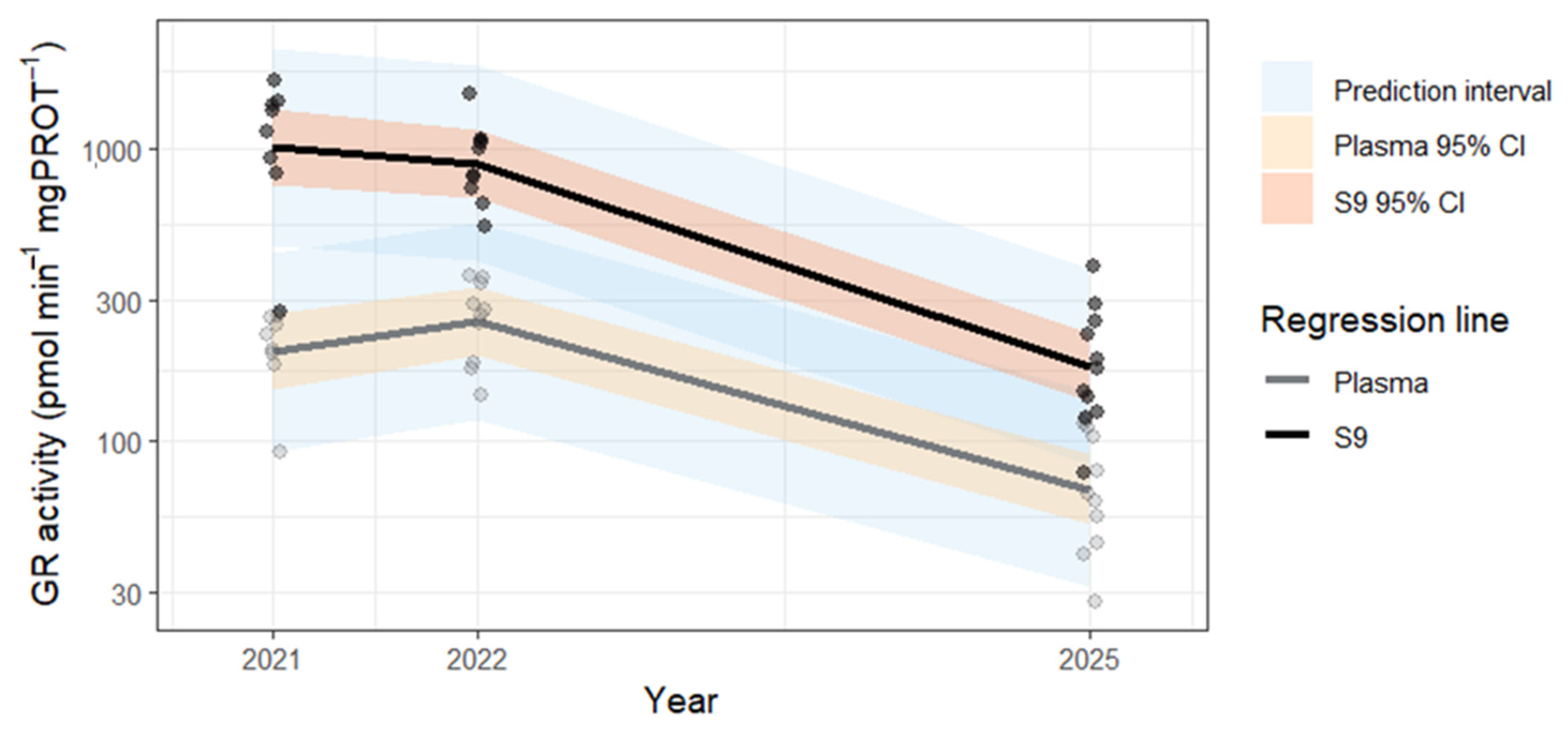

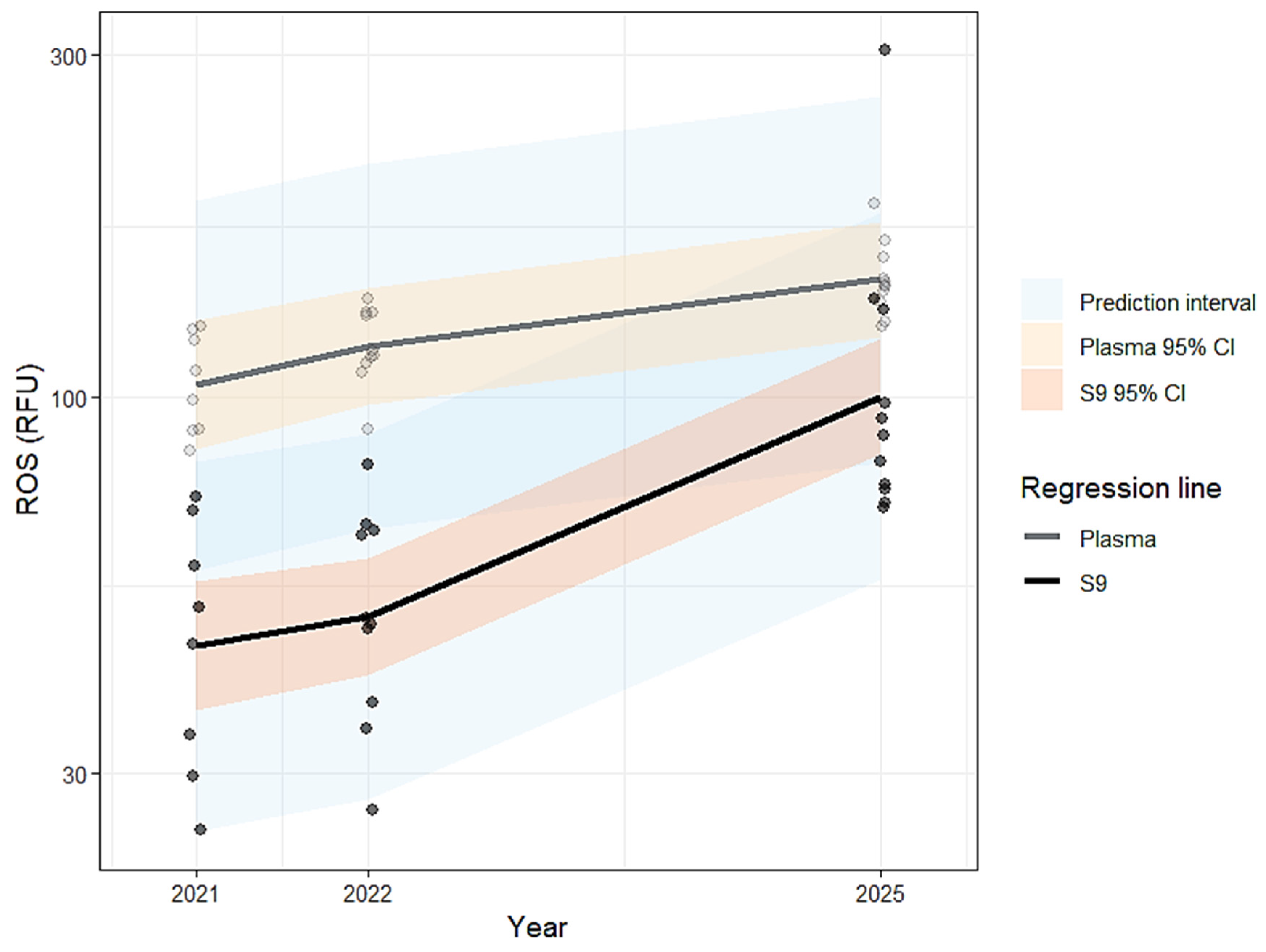

| Biomarker Response | Fraction | 2021 (Ref.) | 2022 (Δ vs. 2021) | 2025 (Δ vs. 2021) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative AChE activity | Plasma | 100 | ↑ +12% | ↑ +20% |

| S9 | 100 | ↑ +53% | ↓ −75% | |

| Relative CES activity | Plasma | 100 | ↓ −35% | ↓ −92% |

| S9 | 100 | ↑ +112% | ↓ −69% | |

| Relative GST activity | Plasma | 100 | ↑ +66% | ↓ −6% |

| S9 | 100 | ↓ −57% | ↓ −96% | |

| Relative GR activity | Plasma | 100 | ↑ +27% | ↓ –65% |

| S9 | 100 | ↓ –18% | ↓ –83% | |

| Relative ROS fluorescence | Plasma | 100 | ↑ +12% | ↑ +40% |

| S9 | 100 | ↑ +8% | ↑ +131% | |

| Relative GSH fluorescence | Plasma | 100 | ↓ −34% | ↑ +24% |

| S9 | 100 | ↑ +10% | ↓ −32% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bjedov, D.; Levak, I.; Velki, M.; Alić, S.; Jurinović, L.; Ječmenica, B.; Ečimović, S.; Mikuška, A. Three Years Later: Landfill Proximity Alters Biomarker Dynamics in White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) Nestlings. Environments 2026, 13, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010034

Bjedov D, Levak I, Velki M, Alić S, Jurinović L, Ječmenica B, Ečimović S, Mikuška A. Three Years Later: Landfill Proximity Alters Biomarker Dynamics in White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) Nestlings. Environments. 2026; 13(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010034

Chicago/Turabian StyleBjedov, Dora, Ivona Levak, Mirna Velki, Sabina Alić, Luka Jurinović, Biljana Ječmenica, Sandra Ečimović, and Alma Mikuška. 2026. "Three Years Later: Landfill Proximity Alters Biomarker Dynamics in White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) Nestlings" Environments 13, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010034

APA StyleBjedov, D., Levak, I., Velki, M., Alić, S., Jurinović, L., Ječmenica, B., Ečimović, S., & Mikuška, A. (2026). Three Years Later: Landfill Proximity Alters Biomarker Dynamics in White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) Nestlings. Environments, 13(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010034