Spatial and Multivariate Analysis of Groundwater Hydrochemistry in the Solana Aquifer, SE Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

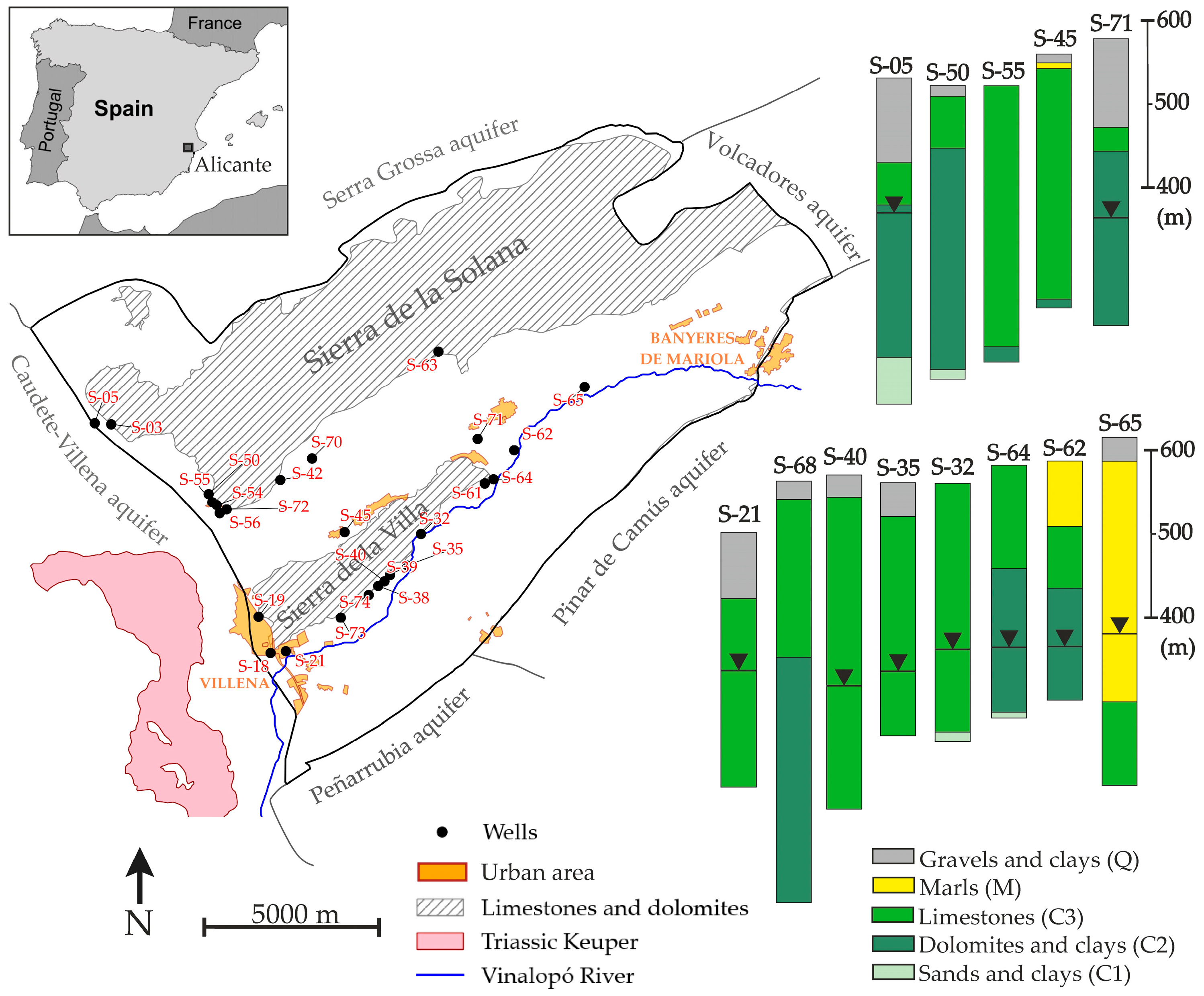

2.1. Study Area Overview

2.1.1. Climate and Recharge Processes

2.1.2. Geology

2.2. Sample Collection and Analysis

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

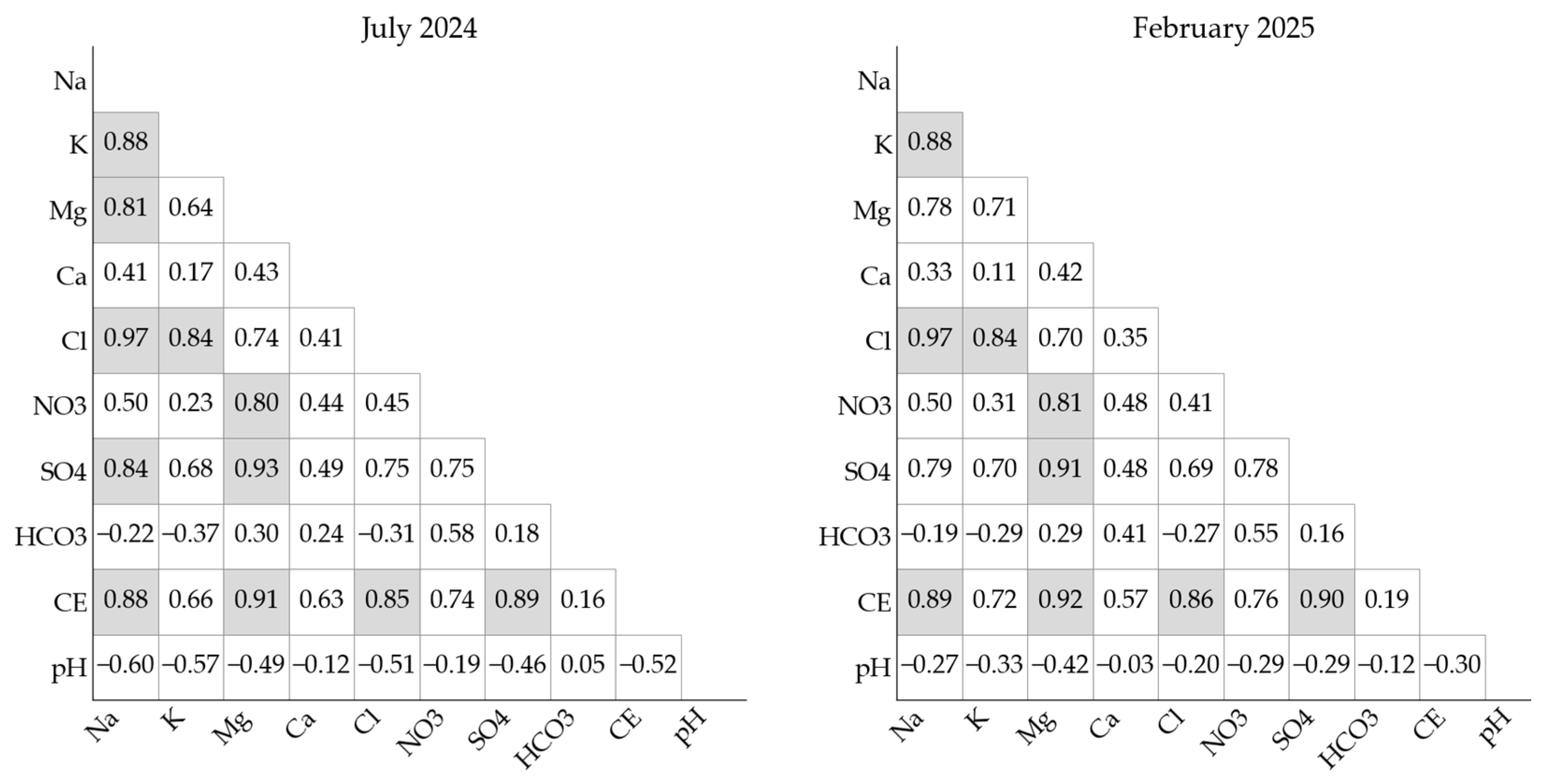

3.1. Hydrochemical Characteristics of Groundwater

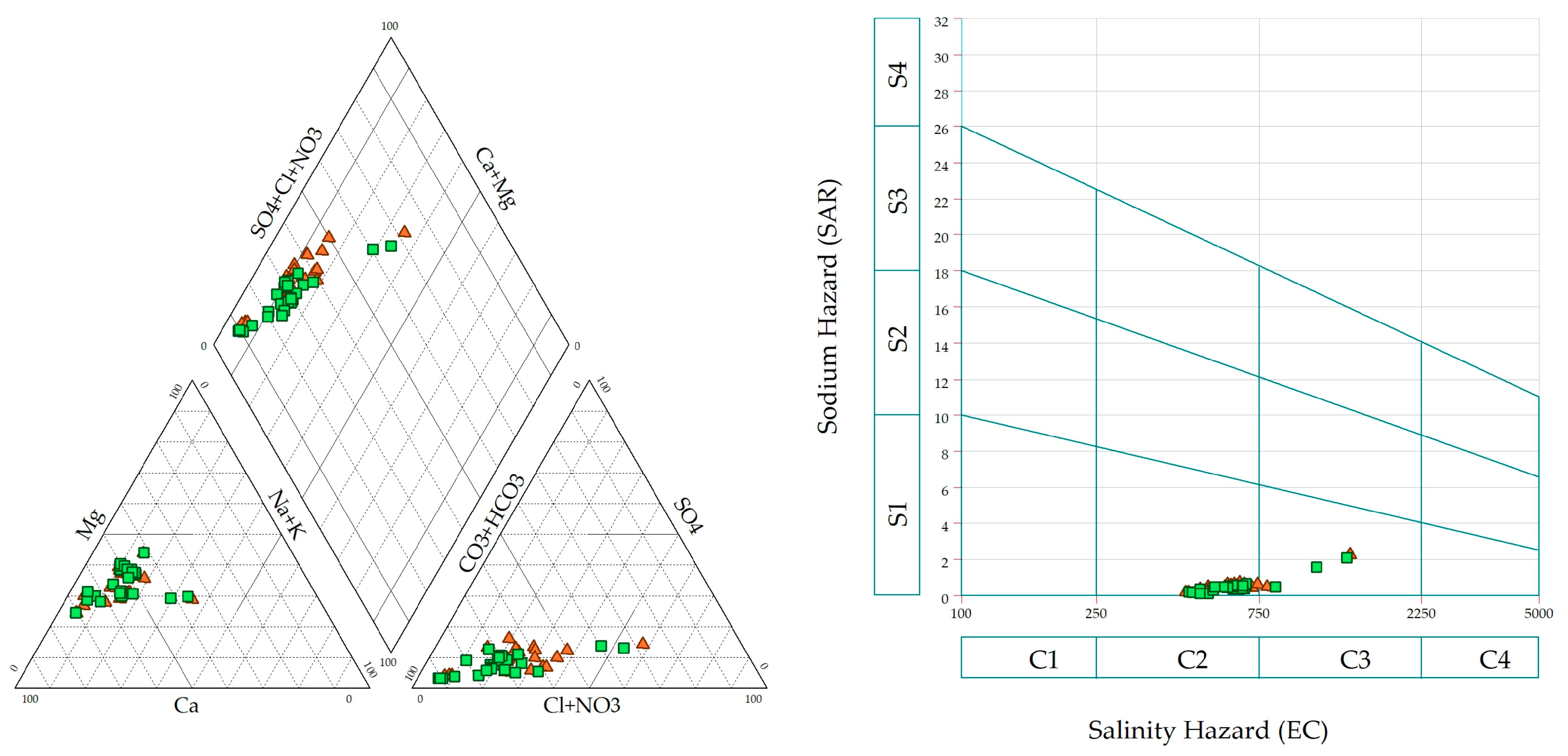

3.2. Hydrochemical Classification and Water Quality Assessment

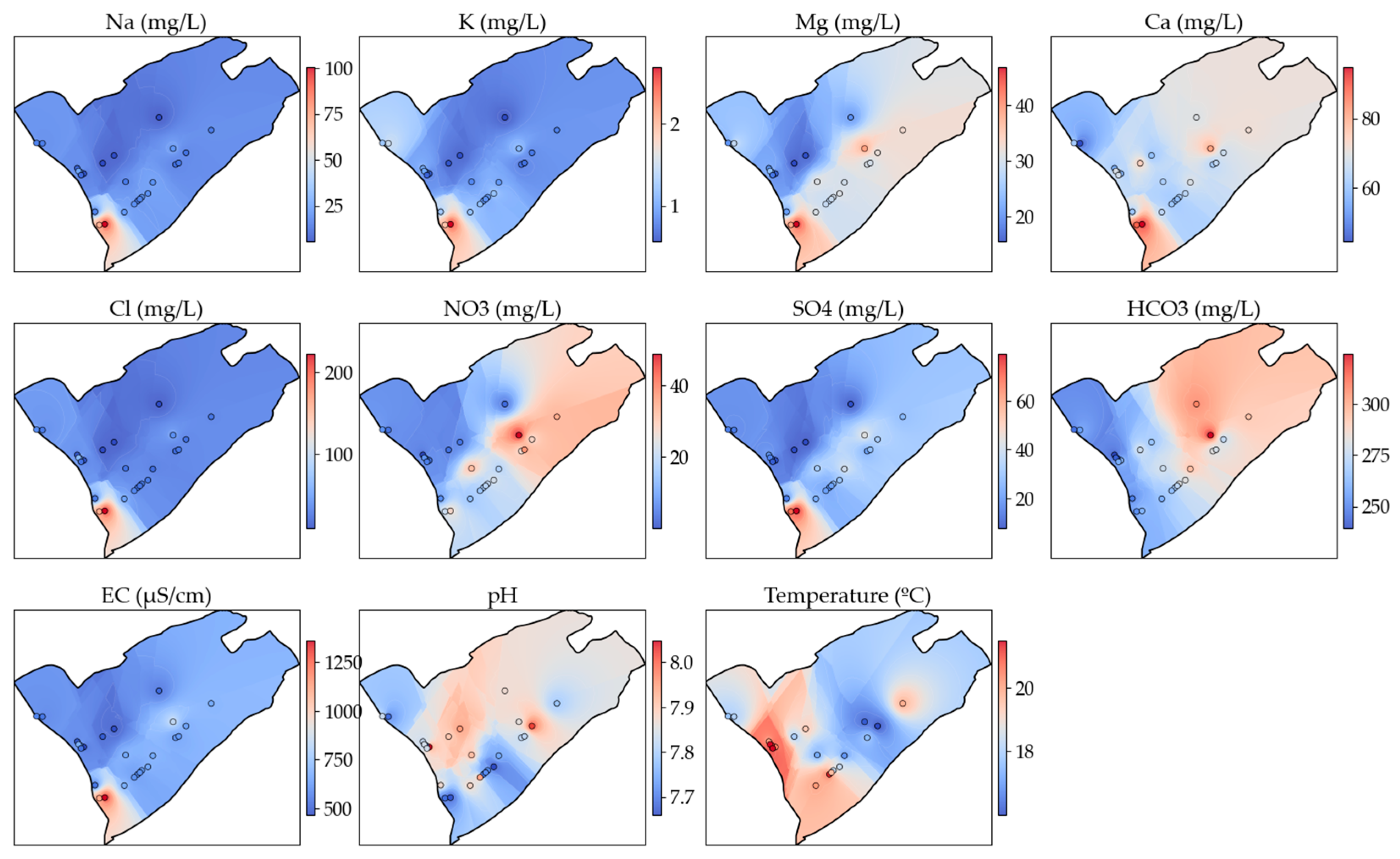

3.3. Spatial Distribution of the Hydrochemical Parameters

3.4. Hydrochemical Variability Analysis Using PCA and HCA

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2024: Water for Prosperity and Peace; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2024; ISBN 978-92-3-100657-9. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000388948 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- UNESCO. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2022: Groundwater: Making the Invisible Visible; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2022; ISBN 978-92-3-100507-7. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000380721 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The State of Food and Agriculture 2023—Revealing the True Cost of Food to Transform Agrifood Systems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrocicco, M.; Colombani, N. The issue of groundwater salinization in coastal areas of the Mediterranean region: A review. Water 2021, 13, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanale, C.; Losacco, D.; Triozzi, M.; Massarelli, C.; Uricchio, V.F. An overall perspective for the study of emerging contaminants in karst aquifers. Resources 2022, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexakis, D.E.; Kiskira, K.; Gamvroula, D.; Emmanouil, C.; Psomopoulos, C.S. Evaluating toxic element contamination sources in groundwater bodies of two Mediterranean sites. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 34400–34409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Custodio, E. Groundwater pollution in Spain: General aspects. J. Inst. Water Environ. Manag. 1992, 6, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Haj, R.; Merheb, M.; Halwani, J.; Ouddane, B. Hydrogeochemical characteristics of groundwater in the Mediterranean region: A meta-analysis. Phys. Chem. Earth. 2023, 129, 103351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Bosch, A.; Vallejos, A.; Martín-Rosales, W.; Molina, L.; Andreu Rodes, J.M.; Calaforra, J.M. La surexploitation dans certains aquifères du sud-est espagnol. In Proceedings of the International Conference on World Water Resources at the Beginning of the 21st Century, Paris, France, 3–6 June 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Custodio, E. Aquifer overexploitation: What does it mean? Hydrogeol. J. 2002, 10, 254–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custodio, E.; Andreu-Rodes, J.M.; Aragón, R.; Estrela, T.; Ferrer, J.; García-Aróstegui, J.L.; Manzano, M.; Rodríguez-Hernández, L.; Sahuquillo, A.; del Villar, A. Groundwater intensive use and mining in south-eastern peninsular Spain: Hydrogeological, economic and social aspects. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 559, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahuquillo, A. La explotación intensa de los acuíferos en la cuenca baja del Segura y en la cuenca del Vinalopó. Ing. Agua 2016, 20, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mammadova, L.; Negri, S. Understanding the impacts of overexploitation on the Salento aquifer: A comprehensive review through well data analysis. Sustain. Futures 2024, 1, 100188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, K.; Taheri, M.; Parise, M. Impact of intensive groundwater exploitation on an unprotected covered karst aquifer: A case study in Kermanshah Province, western Iran. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu Rodes, J.M. Contribución de la Sobreexplotación al Conocimiento de los Acuíferos Kársticos de Crevillente, Cid y Cabeçó d’Or (Provincia de Alicante). Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de Alicante, Alicante, Spain, 6 June 1997. Available online: https://rua.ua.es/dspace/handle/10045/3196 (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Andreu, J.M.; Pulido-Bosch, A.; Llamas, M.R.; Bru, C.; Martínez-Santos, P.; García-Sánchez, E.; Villacampa, L. Overexploitation and water quality in the Crevillente aquifer (Alicante, SE Spain). WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2008, 111, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Geológico y Minero de España; Diputación Provincial de Alicante. Desarrollos Metodológicos en Geología del Subsuelo para la Caracterización de Recursos Hidrogeológicos Profundos de la Provincia de ALICANTE (HIDROPROAL): Modelo Geológico 3D del Acuífero de Solana–Onteniente–Volcadores y Evaluación de las Reservas Totales de Agua Subterránea; Instituto Geológico y Minero de España: Madrid, Spain, 2013; ISBN 978-84-96979-40-6. [Google Scholar]

- Diputación Provincial de Alicante. Mapa del Agua. Provincia de Alicante, 2nd ed.; Diputación Provincial de Alicante: Alicante, Spain, 2007.

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Anuncio de la Confederación Hidrográfica del Júcar sobre declaración en riesgo de no alcanzar el buen estado cuantitativo de la masa de agua subterránea 080.160 Villena-Benejama. Boletín Oficial Del Estado 2020, 266, 45583–45586. Available online: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2020/10/08/pdfs/BOE-B-2020-34158.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Pérez Bielsa, C.; Lambán Jiménez, L.J. Caracterización hidrogeoquímica e isotópica de las aguas subterráneas en el acuífero carbonatado Solana (Alicante). Bol. Geol. Min. 2006, 117, 589–592. [Google Scholar]

- Olcina Cantos, J.; Moltó Mantero, E. Climas y Tiempos del País Valenciano; Publicacions Universitat d’Alacant: Alicante, Spain, 2019; ISBN 978-84-9717-659-0. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Geológico y Minero de España; Diputación Provincial de Alicante—Ciclo Hídrico. Atlas Hidrogeológico de la Provincia de Alicante; IGME–DPA: Madrid/Alicante, Spain, 2015; ISBN 978-84-7840-959-4. [Google Scholar]

- Cantos Conejero, J.M. Estudio hidrogeológico del acuífero detrítico del entorno de Caudete-Villena. Rev. Estud. Albacetenses 2001, 2, 5–43. [Google Scholar]

- American Public Health Association. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 23rd ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-87553-047-5. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, D. Water Quality Assessments: A Guide to the Use of Biota, Sediments and Water in Environmental Monitoring, 2nd ed.; Chapman, D., Ed.; CRC Press (Taylor & Francis Group): London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10304-1; Water Quality—Determination of Dissolved Anions by Liquid Chromatography of Ions—Part 1: Determination of Bromide, Chloride, Fluoride, Nitrate, Nitrite, Phosphate and Sulfate. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Freeze, R.A.; Cherry, J.A. Groundwater; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1979; ISBN 978-0-13-365312-0. [Google Scholar]

- Piper, A.M. A graphic procedure in the geochemical interpretation of water-analyses. Trans. AGU 1944, 25, 914–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simler, R. DIAGRAMMES: Logiciel D’hydrochimie Multilangage [software], Version 9.3; Université d’Avignon: Avignon, France, 2025.

- Wilcox, L.V. Classification and Use of Irrigation Waters; U.S. Geological Survey: Washington, DC, USA, 1955; Circular 969.

- U.S. Salinity Laboratory Staff. Diagnosis and Improvement of Saline and Alkali Soils; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1954. Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/20360500/hb60_pdf/hb60complete.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Thapa, R.; Gupta, S.; Kaur, H. Introducing an irrigation water quality index (IWQI) based on the case study of the Dwarka River basin, Birbhum, West Bengal, India. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2020, 6, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, P.D.; Porter, J.R.; Wilson, D.R. A test of the computer simulation model ARCWHEAT1 on wheat crops grown in New Zealand. Field Crops Res. 1991, 27, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.S. A note on the multiplying factors for various χ2 approximations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1954, 16, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T. Principal Component Analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0387954424. [Google Scholar]

- Abdi, H.; Williams, L.J. Principal component analysis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2001, 2, 433–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.H. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1963, 58, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.A.; Wichern, D.W. Applied Multivariate Statistical Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0131877153. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, M. Chemometrics: Statistics and Computer Application in Analytical Chemistry, 3rd ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2017; ISBN 978-3-527-34097-2. [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike, R.L. Who belongs in the family? Psychometrika 1953, 18, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 978-92-4-154995-0. [Google Scholar]

- Helsel, D.R.; Hirsch, R.M. Graphical data analysis. In Statistical Methods in Water Resources; United States Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, D.; Barberá, J.A.; Mudarra, M.; Andreo, B. Hydrogeochemical tools applied to the study of carbonate aquifers: Examples from some karst systems of Southern Spain. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Márquez, J.M.; Barberá, J.A.; Andreo, B.; Mudarra, M. Geochemical evolution of groundwater in an evaporite karst system: Brujuelo area (Jaén, S Spain). Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2017, 17, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hounslow, A.W. Water Quality Data: Analysis and Interpretation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1995; ISBN 0-8493-9090-2. [Google Scholar]

- Güler, C.; Thyne, G.D.; Mccray, J.E.; Turner, K.A. Evaluation of graphical and multivariate statistical methods for classifcation of water chemistry data. Hydrogeol. J. 2002, 10, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Vasic, L.; Wu, X.; Cao, J.; Milanovic, S. Hydrochemical features and their controlling factors in the Kucaj-Beljanica Massif, Serbia. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ. Psychol. Measur. 1960, 20, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.C.; Sampson, R.J. Statistics and Data analysis in Geology, 3rd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0471172758. [Google Scholar]

- Helena, B.; Pardo, R.; Vega, M.; Barrado, E.; Fernández, J.M.; Fernández, L. Temporal evolution of groundwater composition in an alluvial aquifer (Pisuerga River, Spain) by principal component analysis. Water Res. 2000, 34, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan, D.; Şen, Z.; Öztürk, T. Assessment of Groundwater Quality through Hydrochemistry Using Principal Component Analysis in the Kızılırmak Delta (Turkey). Water 2024, 16, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenico, P.A.; Schwartz, F.W. Physical and Chemical Hydrogeology, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0471597629. [Google Scholar]

- Appelo, C.A.J.; Postma, D. Geochemistry, Groundwater and Pollution, 2nd ed.; CRC Press/Balkema: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.J. Chemometrics in Analytical Spectroscopy; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 1998; ISBN 978-0-85404-555-6. [Google Scholar]

- Everitt, B.S.; Landau, S.; Leese, M.; Stahl, D. Cluster Analysis, 5th ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-470-74991-3. [Google Scholar]

- Elango, L.; Kannan, R. Rock–water interaction and its control on chemical composition of groundwater. In Developments in Environmental Science; Sarkar, D., Datta, R., Hannigan, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 5, pp. 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadori, M.; Pennisi, M.; Masciale, R.; Fidelibus, M.D.; Frollini, E.; Ghergo, S.; Parrone, D.; Preziosi, E.; Passarella, G. Isotopic study for evaluating complex groundwater circulation patterns, hydrogeological zoning, and water-rock interaction in a Mediterranean coastal karst environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 176850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leduc, C.; Pulido-Bosch, A.; Remini, B. Anthropization of groundwater resources in the Mediterranean region: Processes and challenges. Hydrogeol. J. 2017, 25, 1529–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakalowicz, M. Karst groundwater: A challenge for new resources. Hydrogeol. J. 2005, 13, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudry, J. Apport du Traçage Physico–Chimique Naturel à la Connaissance Hydrocinématique des Aquifères Carbonatés. Doctoral Thesis, Université de Franche-Comté, Besançon, France, May 1987. Available online: https://theses.hal.science/tel-00654518 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Ford, D.C.; Williams, P.W. Karst Hydrogeology and Geomorphology, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldscheider, N.; Drew, D.P. (Eds.) Methods in Karst Hydrogeology; CRC Press: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narany, T.S.; Bittner, D.; Disse, M.; Chiogna, G. Spatial and temporal variability in hydrochemistry of a small-scale dolomite karst environment. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu Rodes, J.M.; García Sánchez, E.; Pulido Bosch, A.; Jorreto, S.; Francés, I. Influence of Triassic deposits on water quality of some karstic aquifers to the south of Alicante (Spain). Estud. Geol. 2010, 66, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Gavilán, P. Caracterización Hidrogeológica de Acuíferos Carbonáticos del sur de España a Partir de sus Respuestas Naturales. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, España, 12 July 2010. Available online: https://digibug.ugr.es/handle/10481/5641 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Pardo-Igúzquiza, E.; Durán, J.J.; Robledo-Ardila, P.A. A Three-Dimensional Karst Aquifer Model: The Sierra de Las Nieves Case (Málaga, Spain). In Hydrogeological and Environmental Investigations in Karst Systems. Environmental Earth Sciences; Andreo, B., Carrasco, F., Durán, J., Jiménez, P., LaMoreaux, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Bosch, A. Investigación y exploración de acuíferos kársticos. Bol. Geol. Min. 2001, 112, 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, S.S.D.; Chilton, P.J. Groundwater: The processes and global significance of aquifer pollution. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2003, 358, 1957–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, D.C.; Kim, Y.-C.; Lee, J.-Y.; Ko, K.-S.; Lee, S.-G.; Kim, K.-M.; Kim, T.-Y.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, C.-W.; Kim, D.-Y.; et al. Impact of leaky wells on nitrate cross-contamination in a layered aquifer system: Methodology for and demonstration of quantitative assessment and prediction. J. Hydrol. 2016, 540, 1068–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy. Off. J. Eur. Communities 2000, L327, 1–73. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32000L0060 (accessed on 4 August 2025).

| July 2024 | February 2025 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Min | Max | SD | Mean | Min | Max | SD | |

| Na+ | 21.7 | 5.6 | 100.6 | 20.1 | 22.1 | 5.6 | 109.6 | 20.6 |

| K+ | 1.1 | 0.6 | 2.7 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 2.7 | 0.5 |

| Mg2+ | 27.5 | 15.5 | 47.0 | 7.5 | 28.9 | 15.4 | 47.7 | 7.7 |

| Ca2+ | 66.5 | 44.6 | 95.0 | 9.9 | 70.8 | 47.4 | 96.6 | 9.5 |

| Cl− | 43.7 | 9.0 | 223.7 | 46.6 | 48.8 | 10.0 | 248.2 | 48.7 |

| NO3− | 17.0 | 0.0 | 48.9 | 12.4 | 19.8 | 3.5 | 53.4 | 14.4 |

| SO42− | 26.0 | 7.7 | 79.7 | 17.4 | 29.1 | 8.2 | 88.5 | 18.0 |

| HCO3− | 270.4 | 239.4 | 324.7 | 20.3 | 226.2 | 198.9 | 274.7 | 17.9 |

| EC | 659.5 | 467.0 | 1363.0 | 190.8 | 648.2 | 458.0 | 1392.0 | 187.6 |

| pH | 7.8 | 7.7 | 8.1 | 0.1 | 7.8 | 7.6 | 8.0 | 0.1 |

| T | 19.0 | 16.0 | 21.5 | 1.7 | 16.7 | 13.2 | 20.3 | 2.1 |

| July 2024 | February 2025 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | |

| Na+ | 11.0 | 85.8 | 15.2 | 18.5 | 109.6 | 20.0 | 13.4 | 17.3 |

| K+ | 0.7 | 2.3 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| Mg2+ | 20.7 | 42.4 | 25.8 | 28.2 | 47.7 | 28.4 | 22.0 | 28.1 |

| Ca2+ | 59.5 | 91.8 | 66.4 | 65.0 | 96.6 | 72.0 | 67.2 | 70.9 |

| Cl− | 18.6 | 191.8 | 32.7 | 31.5 | 248.2 | 44.7 | 27.2 | 38.4 |

| NO3− | 9.7 | 24.4 | 16.6 | 18.2 | 28.2 | 21.1 | 10.8 | 21.5 |

| SO42− | 13.2 | 74.6 | 20.6 | 26.1 | 88.5 | 28.3 | 14.7 | 25.6 |

| HCO3− | 268.2 | 257.7 | 269.3 | 276.0 | 217.0 | 226.0 | 221.2 | 229.6 |

| EC | 522.3 | 1234.0 | 611.3 | 634.0 | 1392.0 | 629.5 | 529.7 | 615.4 |

| pH | 7.9 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sala-Sala, V.; Andreu, J.M.; Pérez-Gimeno, A.; Jordán, M.M.; Navarro-Pedreño, J.; Almendro-Candel, M.B. Spatial and Multivariate Analysis of Groundwater Hydrochemistry in the Solana Aquifer, SE Spain. Environments 2025, 12, 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12090323

Sala-Sala V, Andreu JM, Pérez-Gimeno A, Jordán MM, Navarro-Pedreño J, Almendro-Candel MB. Spatial and Multivariate Analysis of Groundwater Hydrochemistry in the Solana Aquifer, SE Spain. Environments. 2025; 12(9):323. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12090323

Chicago/Turabian StyleSala-Sala, Víctor, José Miguel Andreu, Ana Pérez-Gimeno, Manuel M. Jordán, Jose Navarro-Pedreño, and María Belén Almendro-Candel. 2025. "Spatial and Multivariate Analysis of Groundwater Hydrochemistry in the Solana Aquifer, SE Spain" Environments 12, no. 9: 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12090323

APA StyleSala-Sala, V., Andreu, J. M., Pérez-Gimeno, A., Jordán, M. M., Navarro-Pedreño, J., & Almendro-Candel, M. B. (2025). Spatial and Multivariate Analysis of Groundwater Hydrochemistry in the Solana Aquifer, SE Spain. Environments, 12(9), 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12090323