1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified the workplace as an ideal setting for health promotion because it provides a prime environment for influencing people’s health behaviors. Even in countries with high unemployment rates, most of the adult population is still employed, making the workplace a strategic platform for improving public health [

1,

2]. Since 2003, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has supported the integration of measures to protect occupational safety and health with interventions to promote the health and well-being of workers. Adherence to proper nutrition and active lifestyle is, to date, a key part of workplace health promotion (WHP) programs. In Italy, the National Strategic Plan for Prevention drafted for the five-year period 2020–2025 calls for the need to adopt more effective intervention models for strengthening the overall health of workers, such as the WHO Healthy Workplace Model and the NIOSH Total Worker Health Model. The evolution of the WHP concept led, in 2011, to the creation of the Total Worker Health

® (TWH) program. The Total Worker Health

® approach is defined as a set of policies, programs and practices that integrate protection from occupational safety and health hazards with the promotion of injury and illness prevention initiatives to improve worker well-being. Worker well-being is an integrative concept that characterizes quality of life in relation to individual health and work-related environmental, organizational and psychosocial factors [

3]. Poor nutrition is a modifiable and preventable risk factor that can lead to the onset or worsening of some chronic noncommunicable diseases. As is well known, habitual consumption of unhealthy foods can result in weight gain and subsequent obesity [

4], which in turn influence the development of chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular problems and diabetes [

5,

6]. Adherence to a proper diet is therefore, to date, a key part of workplace health promotion programs. The Mediterranean diet, recognized by UNESCO as an intangible heritage of humanity, represents a healthy eating pattern, rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, fish, olive oil and moderate consumption of wine. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with numerous health, socio-cultural, economic and environmental benefits [

7] that make it one of the healthiest and most sustainable food models [

8]. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet also results in lower mortality from cardiovascular and neoplastic diseases [

9], and in addition to health effects, additional benefits include low environmental impact, biodiversity of products consumed, high socio-cultural value of foods and support for the local economy [

10]. Sedentariness is a condition that can be fostered by the type of work performed, but it can also be a habit maintained in leisure time [

11]. In Europe, it is estimated that more than 35 percent of people sit for more than 7 h a day [

2]. In Italy, sedentary behavior, determined by long periods spent standing or sitting, throughout the day, is also widespread among the active adult population. According to the PASSI survey in the two-year period 2021–2022, among adults living in Italy, the “physically active” are 47% of the population, the “partially active” 24% and the “sedentary” 29% [

12]. Existing scientific evidence shows that physical activity is a protective factor for health. The level of exercise is inversely related to mortality risk and thus associated with longer life expectancy [

13]. Regular practice of adequate aerobic physical activity has been shown to act as a protective factor against high-incidence diseases in the general population, such as cardiovascular disease. For example, compared with inactive individuals, those who exercise for an average of 92 min per week or 15 min a day had a 14% reduced risk of all-cause mortality (0·86, 0·81–0·91) and had a 3-year longer life expectancy [

14]. The primary purpose of this study is to assess the need for corrective health promotion interventions aimed at improving the lifestyle of young adults. Given that Italian university students engaged in internships are regarded as workers when exposed to health and safety risks, the occupational context represents an ideal setting for health promotion. Specifically, the study seeks to examine the dietary habits and metabolic health of young adults enrolled in health-related degree programs at Vanvitelli University in Naples, with a focus on adherence to the Mediterranean diet, the intensity of daily physical activity and body mass index (BMI).

2. Materials and Methods

A prospective observational epidemiological study was conducted to assess proper lifestyles in terms of adherence to the Mediterranean diet and performance of physical activity in a population of young adults enrolled in health-related degree programs. The study involved the administration of questionnaires during preventive visits carried out as part of the University’s Health Surveillance Program as well as the direct detection of participants’ weight and height. The study population is represented by students in the first year of the degree courses of the following health professions of the “Luigi Vanvitelli” University: Dentistry and Dental Prosthetics, Physiotherapy, Speech Therapy, Psychiatric Rehabilitation Technique, Neuropsychomotricity Therapy, Biomedical Laboratory Techniques, Orthotics, Medical Radiology Techniques, Dental Hygiene and Prevention Techniques in the Environment and Workplaces, and students attending the third year of the degree course in Medicine and Surgery.

Inclusion criteria were students equated with workers under Article 2 of Legislative Decree 81/2008 and belonging to the 18–34 age group. Exclusion criteria included the following: (1) the presence of known chronic diseases that affect metabolism or appetite; (2) the presence of pathologies or disabilities that prevent a proper active lifestyle; (3) pregnancy status; (4) taking medications that affect body weight or physical activity; and (5) failure to sign the informed consent. Indeed, the subjects involved in the study are students attending health study courses, subjected to preventive visits carried out as part of the University Health Surveillance Program, prior to the commencement of their internships and clinical placements. Therefore, recruitment was planned during the scheduled preventive visits. An information sheet on data processing for experimental purposes and an explanatory sheet on the contents and objectives of the study were distributed during the students’ access to the University Health Surveillance Service. Informed consent was then collected using the forms prepared for data collection, processing and publication. Two questionnaires, one related to adherence to the Mediterranean diet (PREDIMED) and one to daily physical activity (IPAQ), were administered during the medical examination, and body weight and height measurements were taken with standardized instruments for calculating BMI.

2.1. PREDIMED and IPAQ Questionnaires

The PREDIMED (PREvención con DIeta MEDiterránea) questionnaire was designed to assess adherence to the Mediterranean diet. It is mainly used in the PREDIMED study, a major clinical trial that analyzed the effects of the Mediterranean diet on cardiovascular disease prevention [

15]. The questionnaire contains 14 questions that address the consumption of specific foods (e.g., fruits, vegetables, legumes, fish, olive oil), indicating frequency, portions and eating habits (e.g., use of fat from seasoning). The result of the PREDIMED questionnaire is a score (varying between 1 and 14), the interpretation of which involves division into 3 classes: 1–5, poor adherence; 6–9 medium adherence; and greater than 10, good adherence.

The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) is designed to measure adults’ physical activity in various settings and is used to quantify physical activity level to assess adherence to international physical activity recommendations and to correlate physical activity levels with various health conditions. For this study, the IPAQ-S (Short Form), a short questionnaire about physical activity performed in the past 7 days, was used. It consists of 7 questions and measures time spent in physical activities of different intensities (light, moderate and vigorous) and time spent sitting [

16]. The result of the IPAQ questionnaire is reported in MET (Metabolic Equivalent of Task), which is the unit of measurement that estimates the amount of energy used by the human body during an activity compared to when at rest. Based on the frequency of activity during the past 7 days, a subject is described as inactive (<700 METs), sufficiently active (701–2519 METs) and active (>2520 METs).

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Each participant was assigned an anonymous ID to comply with the principles established by the GDPR. The collected data were organized into a structured database using Microsoft Excel (Office 365 version), where each row represented an individual participant and the columns contained the variables of interest. The database was exported for statistical analysis conducted with JASP software 0.19.3, while Julius AI, a specialized artificial intelligence system utilizing Python 3.11.6-based data science libraries (pandas for data manipulation, matplotlib and seaborn for visualization and scipy/statsmodels for statistical validation), was employed to generate graphical visualizations and validate the accuracy of statistical analyses. To ensure the integrity and quality of the data, periodic checks were conducted for completeness and accuracy, and any changes or corrections were documented.

4. Discussion

Italian Legislative regarding Health and Safety at Work has put trainees, interns and apprentices on the same footing as workers, recognizing their rights and protections in the workplace. This legislation is particularly important for a segment of the population that is going through a delicate phase of the life cycle, marked by fundamental choices such as the completion of studies, entry into the world of work and the development of social and territorial relations. Consequently, it is crucial to understand their state of well-being and monitor its evolution over time, as these challenges can profoundly affect not only their psychological health, but also their lifestyles, including diet and physical activity. In fact, as reported in the previous paragraph, while numerous studies demonstrate the positive impact of healthy eating habits on general health, research shows a progressive abandonment of the Mediterranean diet among young Italians, despite its documented benefits for the prevention of chronic diseases and for psychophysical well-being [

17]. Young adults face intense life rhythms and social pressures that often lead them to prefer convenience and processed foods, which meet their needs for convenience but do not fully satisfy their nutritional needs [

18]. In addition, there is a growing tendency towards physical inactivity, often sacrificed due to stress and study or workloads [

19].

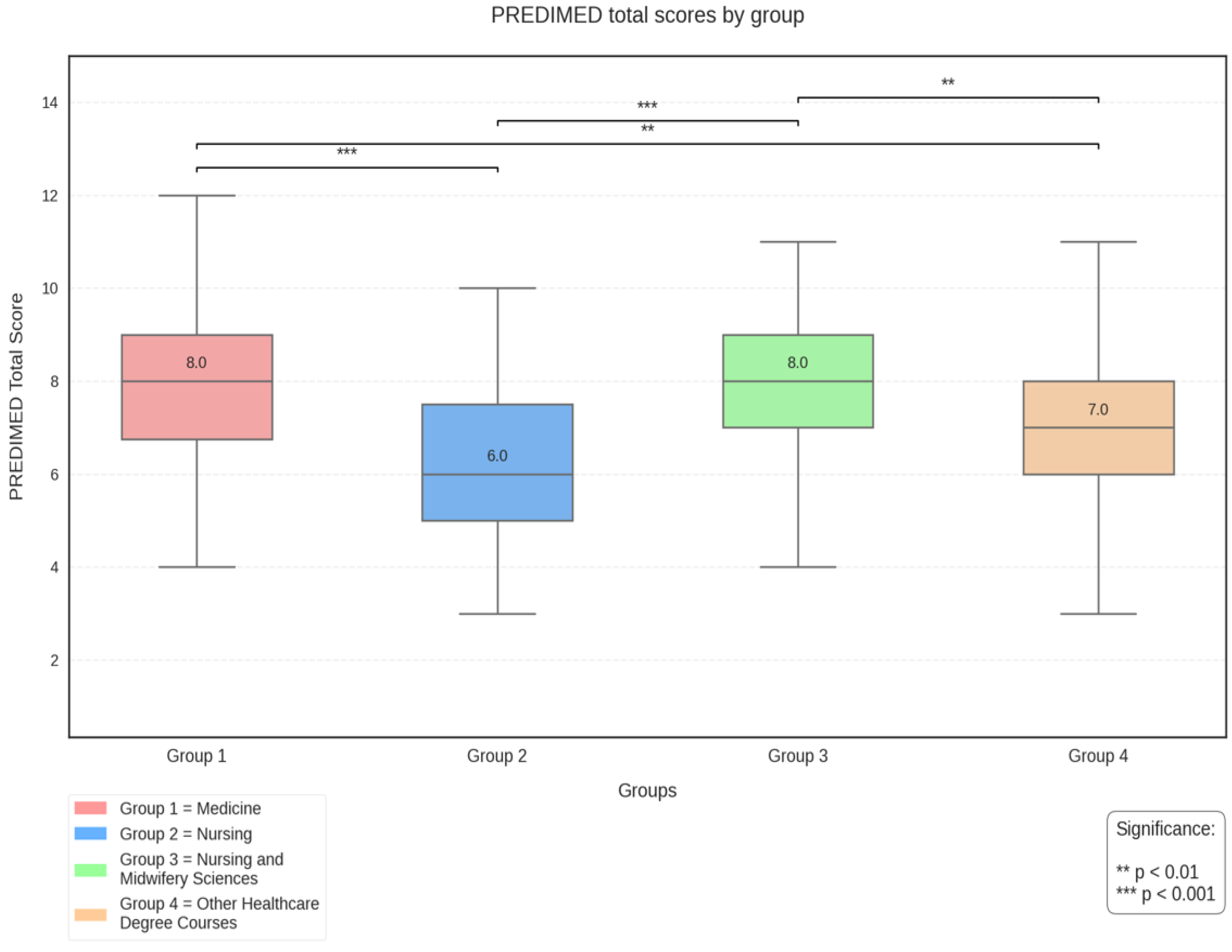

The analysis conducted in this work revealed significant differences in adherence to the Mediterranean diet between the different groups of healthcare workers, while no gender-related differences emerged. In particular, Group 2 (nurses) showed lower scores than the other groups, suggesting the need for possible targeted interventions for this group. The analysis of the individual responses to the questions of the PREDIMED questionnaire revealed interesting patterns in the distribution of positive responses among the participants (where ‘positive’ refers to the response indicating greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet). The questions with the highest rate of positive responses were those on the use of extra virgin olive oil (95.5%), less use of butter or margarine (90.5%) and low consumption of sugary drinks (81.4%). On the other hand, the questions with the lowest rate of positive answers were those on the consumption of wine (1.2%), fruit (10.3%) and fish (23.6%). Also interesting were the data on the consumption of vegetables (two or more portions per day for only 44.6%) and red meat and sausages (more than one portion per day for 41.3%). While virtuous behavior is observed in the use of healthy fats (extra virgin olive oil) and in limiting saturated fats (butter and margarine), significant criticism emerges in the low consumption of fundamental foods of the Mediterranean diet such as fruit, vegetables and fish, as well as in the excessive consumption of red meat and sausages for a good percentage of participants. It should be remembered that even the most recent WHO recommendations indicate the introduction in the diet of at least five portions of fruit and vegetables per day and two to three portions of fish per week and the reduction in red meat to once a week, while sausages should be avoided.

Concerning wine consumption, the latest scientific evidence is challenging the traditional paradigm of the benefits of moderate alcohol consumption. In particular, a meta-analysis published in 2023 [

20] provided significant results that contradict previous beliefs on the subject, demonstrating the absence of a statistically significant correlation between moderate alcohol consumption and reduced mortality in general, thus disproving previously accepted assumptions about the supposed cardioprotective effects and other health benefits of alcohol taken in low doses. This new perspective finds further support in the official WHO position: there is no threshold of alcohol consumption that can be considered completely safe for an individual’s health. These findings are particularly important in the context of the Mediterranean diet, whose moderate consumption of wine is historically considered one of its defining elements. Thus, the very low percentage of daily wine drinkers revealed in the study seems to be positive and not negative. The study shows that the surveyed population generally has a good propensity for moderate physical activity, especially when compared to regional data (17.3% partially active and 34.4% active). Taking the WHO guidelines for physical activity as a reference [

11], to achieve substantial health benefits, adults should perform 150 to 300 min of moderate aerobic activity per week, 75 to 150 min of intense aerobic activity per week or an equivalent combination of both within the week. In general, the majority of students in all groups exceed the WHO minimum recommendations, with a relatively low percentage (between 8.3% and 12.5% depending on the graduating class group) not reaching the minimum recommended levels.

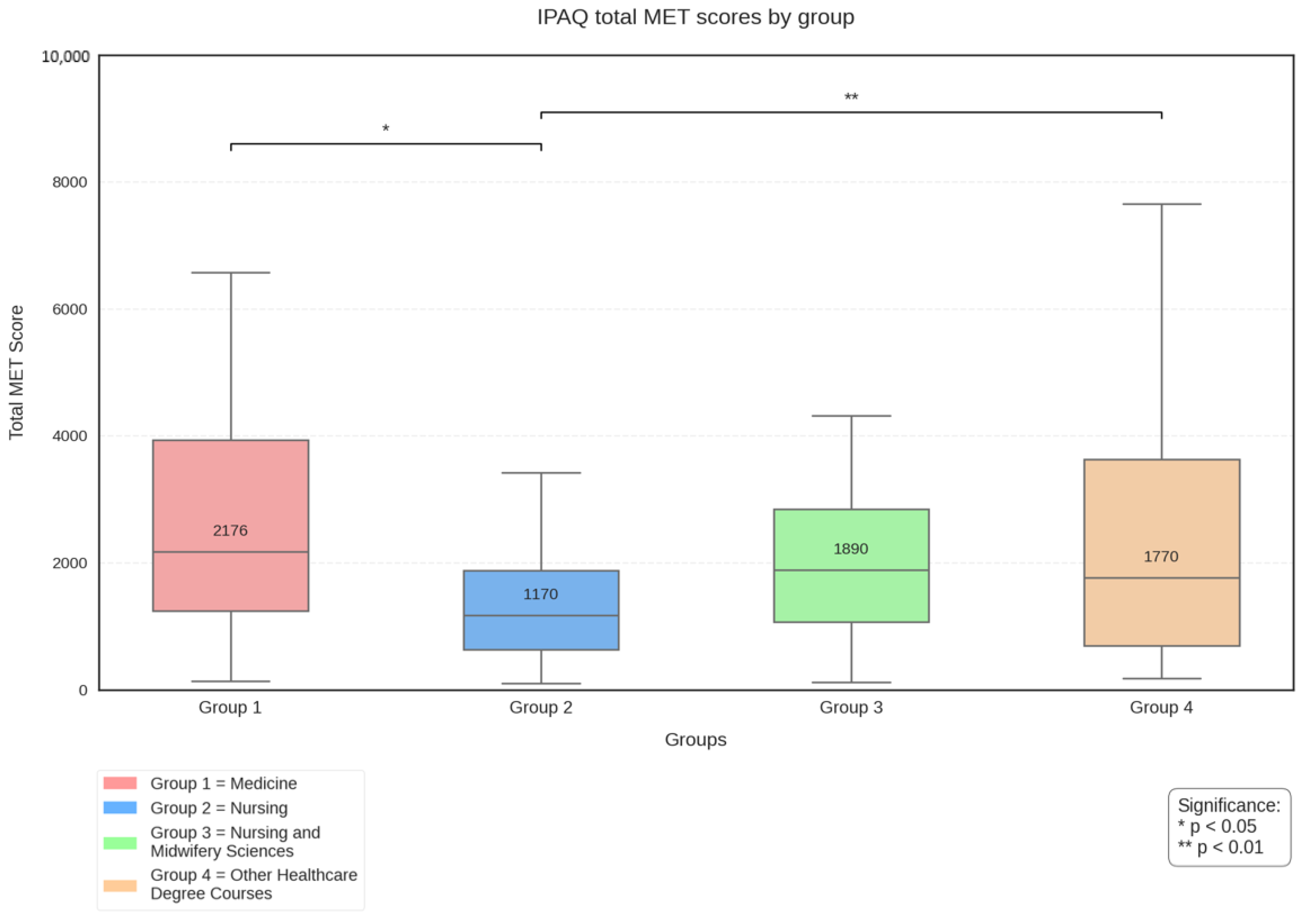

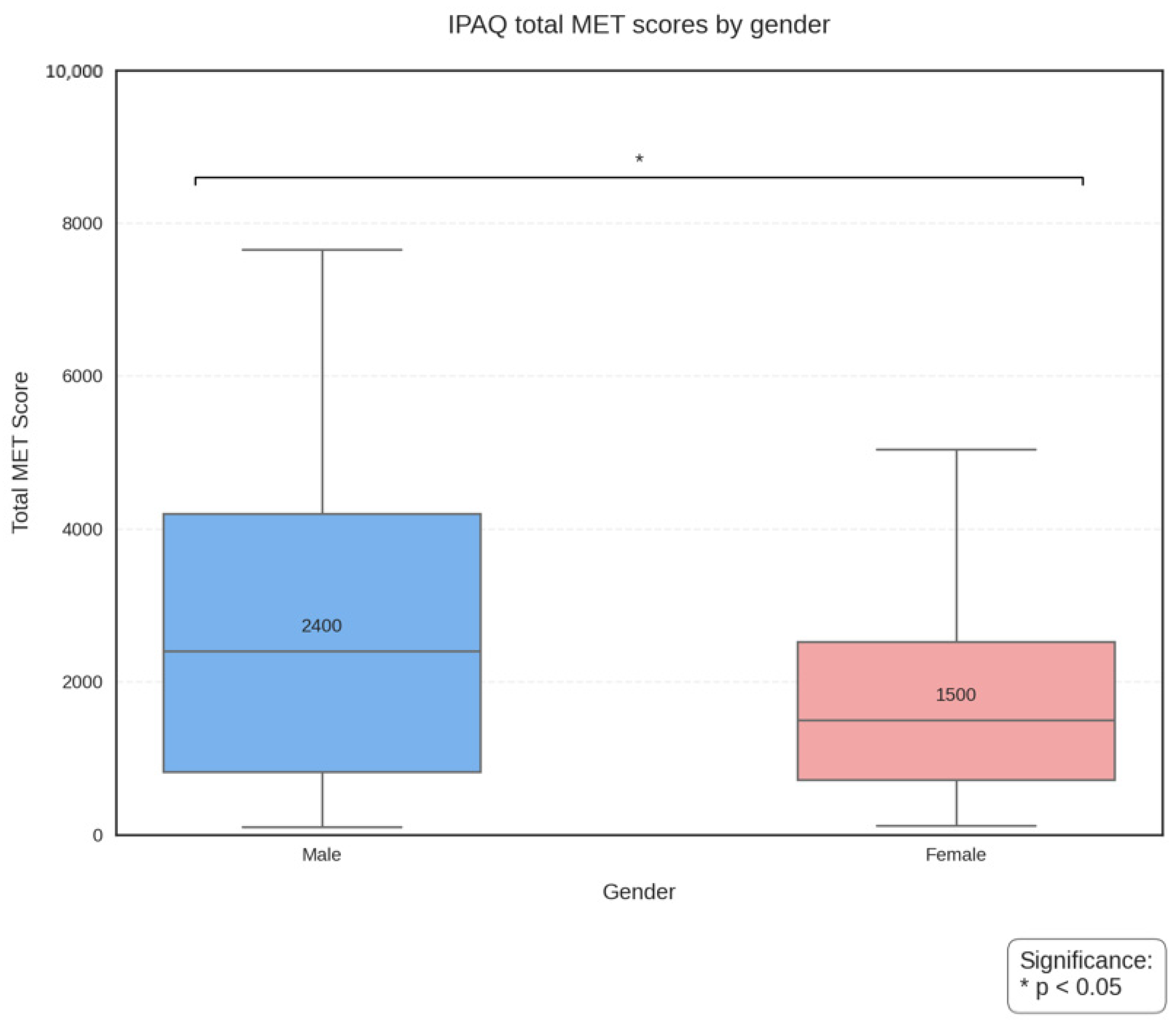

Examination of the four groups by degree course, however, revealed significant differences in the distribution of physical activity levels. Contingency table analysis showed a statistically significant association between occupational group and level of physical activity, while analysis of variance for total METs revealed significant differences between Group 2 (Nursing) compared to students in Medicine and other degree courses. The observed differences could be attributed to various factors, including workloads, schedules and the specific characteristics of each health profession, but it is clear that nursing students/workers are again a group worthy of attention for possible health promotion interventions. Similarly, the results regarding gender-related physical activity levels suggest that particular attention should be paid to the female gender when designing interventions to promote physical activity. Despite the sample being predominantly female (66.9%), 49% of men reached a level of physical activity, compared to 26% of women, indicating a greater male propensity for engaging in regular and high-intensity physical activity. On the other hand, the percentage of individuals with poor physical activity levels was higher among women (24.7%) compared to men (20.0%). Previous studies have demonstrated significant gender differences in physical activity levels among university students [

21], with females generally engaging in less vigorous physical activity than their male counterparts. These differences may be influenced by multiple factors, including socio-cultural barriers, psychological aspects and environmental constraints. Eventual gender-specific barriers and motivators should be carefully considered when designing workplace health promotion programs.

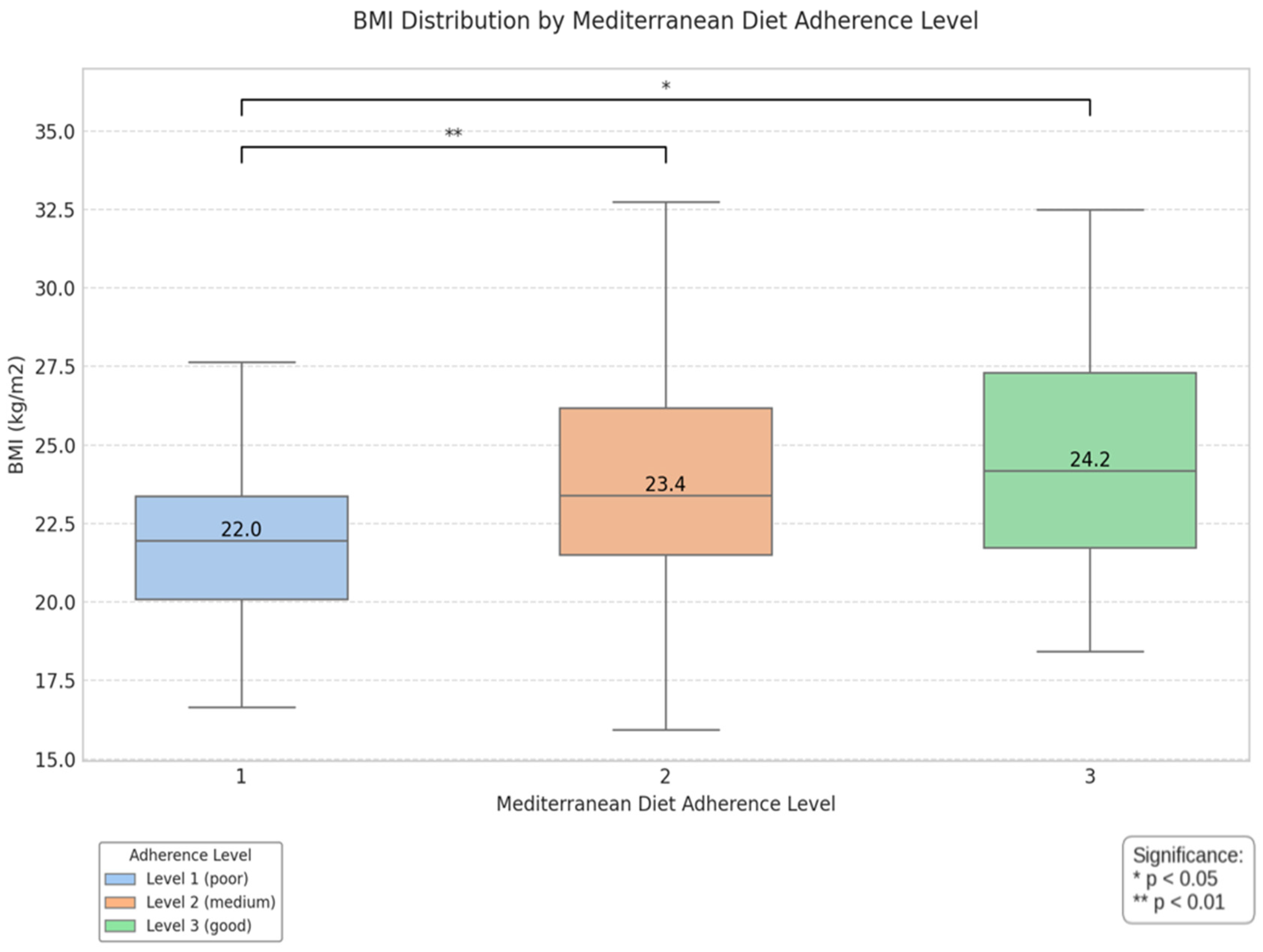

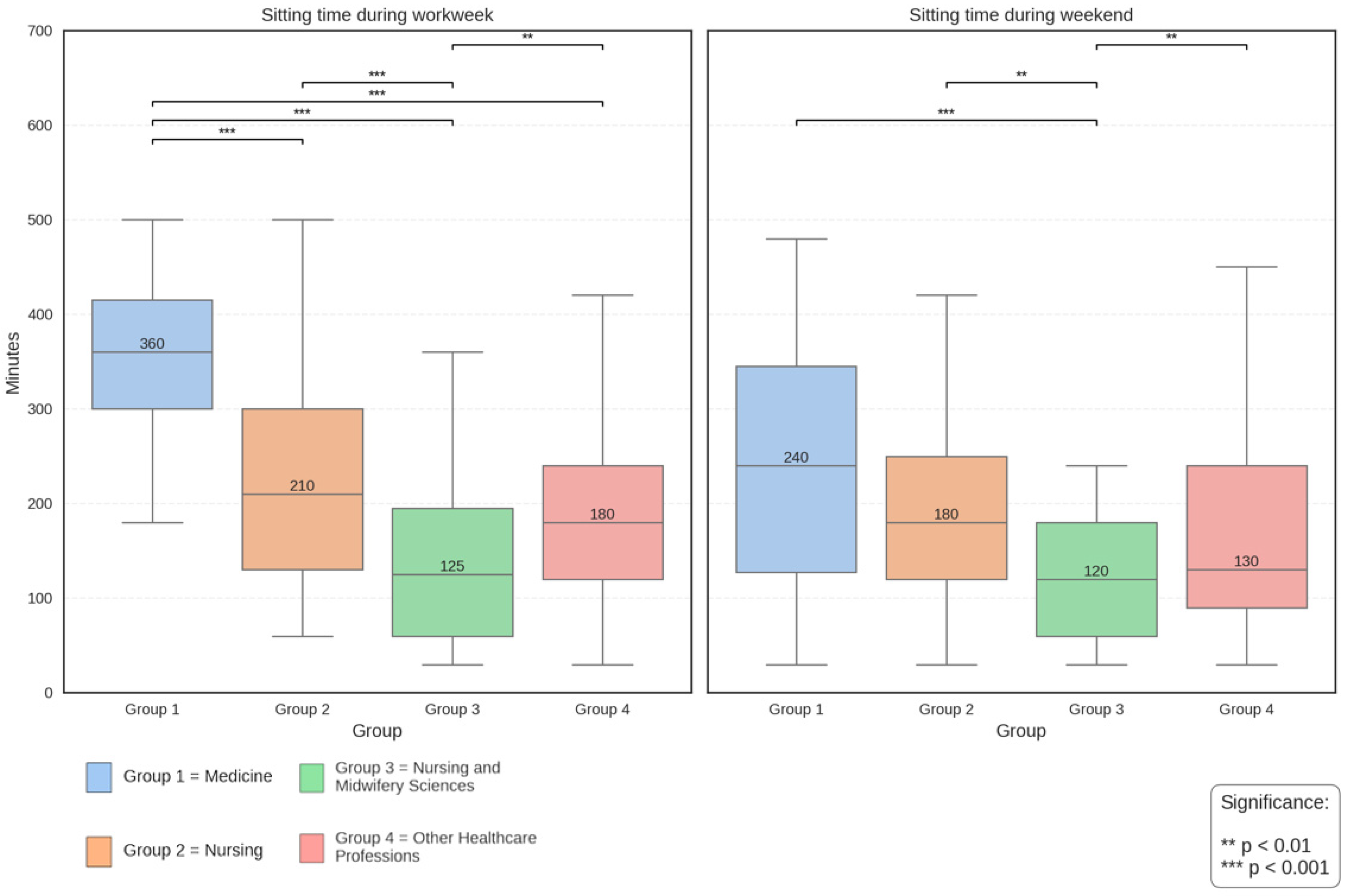

The assessment of the level and quality of physical activity performed cannot be separated from the analysis of sedentary habits. This analysis is based on the separate examination of time spent sitting on working days and days off (questions from the IPAQ questionnaire). In particular, Group 1 (Medicine) shows the highest levels of sedentariness during the working day (365.0 ± 124.0 min), followed by Group 2 (Nursing) with 245.6 ± 170.3 min and Group 4 (Other Health Professions) with 224.1 ± 144.3 min. Group 3 (Nursing and Midwifery) presents the lowest levels of sedentary work. On rest days, a trend towards a reduction in sedentary time is observed in all groups, with Group 1 maintaining the highest values, while Group 3 confirms the lowest levels. Interestingly, the differences between the groups decrease on rest days, suggesting a homogenization of behavior outside the work environment. Since there is moderate evidence that correlates a sedentary lifestyle with increased mortality from all causes (cardiovascular diseases and cancer in particular), but there are no minimum levels at which sedentariness is not considered harmful, it is advisable to raise awareness among the population to remain as active as possible in their free time, since exceeding the recommended minimum levels of moderate-to-intense physical activity established by the WHO may reduce the negative effects associated with sedentariness. The positive correlation between the level of adherence to the Mediterranean diet and BMI on the Kruskal–Wallis test, with a significant difference especially between poor and good adherence, would seem to be counterintuitive to traditional expectations of the benefits of the Mediterranean diet; in reality, this suggests the presence of more complex dynamics in the relationship between dietary patterns and body composition. The surveyed population generally has a good propensity for moderate physical activity, especially when compared to regional data (17.3% partially active and 34.4% active), with significant differences in the distribution of physical activity levels.

Although the PREDIMED questionnaire is a validated tool for assessing adherence to the Mediterranean diet, it has inherent limitations. In particular, it does not consider the amounts of food actually consumed, but relies primarily on the frequency of food intake. This methodological feature could mask substantial differences in total caloric intake between individuals who instead show similar adherence scores. In addition, interpretation of the results must take into account an important confounding factor: overweight people very often tend to seek the advice of nutrition professionals and adopt healthier eating patterns, such as the Mediterranean diet. This could explain the seemingly counterintuitive correlation between higher BMI and greater dietary adherence. However, in the absence of information on the duration and timing of nutrition initiation, it is impossible to determine the causal direction of this relationship.

Regarding physical activity level, the Kruskal–Wallis test shows that there are no statistically significant differences in BMI values (p = 0.0698 > 0.05), although level 2 (Sufficient) shows slightly higher BMI values, but this difference is not statistically significant. Finally, it is interesting to note that there is a weak but significant positive correlation between the parameters of physical activity levels and adherence to the Mediterranean diet (r = 0.16; p = 0.01; χ2 = 11.98; p = 0.017). This may suggest that there is a tendency, albeit modest, to associate higher levels of physical activity with greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet and vice versa, and that targeted health promotion interventions aimed at filling individual gaps in terms of information and education on these issues could be effective tools for improving lifestyles in general. Based on the analysis of the data collected, the discrepancy between some WHO recommendations and detected eating habits suggests the need to implement nutrition education programs for young health workers, focusing particularly on the nursing graduating class. It would be absolutely strategic to develop strategies to encourage general consumption of fruits, vegetables and fish and, at the same time, promote greater awareness of the importance of following international nutritional guidelines. The analysis of adherence to the Mediterranean diet showed different dietary patterns among the professional groups examined, with the nursing student group showing lower average adherence values than the other groups examined. In addition, the discrepancy observed between the eating habits of all participants and the WHO nutritional recommendations regarding the consumption of certain foods underscores the need for targeted educational interventions.

Regarding physical activity, the results showed a general propensity for moderate physical activity, with a relatively low percentage of individuals not reaching the minimum levels recommended by WHO. However, the significant differences found between occupational groups and between genders suggest the need for a differentiated approach in the design of physical activity promotion interventions. In particular, the nursing student group showed significantly lower levels of total physical activity, a finding that, combined with lower adherence to the Mediterranean diet, configures a risk profile that requires special attention. The assessment of sedentary behaviors also revealed significant differences between the groups, with the medical group showing the highest levels of sedentariness during the workday. This finding underscores the importance of implementing strategies to reduce time spent sitting, considering that it is an independent risk factor for many chronic diseases.

Finally, a weak but significant positive correlation was found between the parameters of physical activity levels and adherence to the Mediterranean diet, suggesting that there is a tendency, albeit modest, to associate higher levels of physical activity with greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet and vice versa, and that could target health promotion interventions. Another interesting finding from the study is the positive, albeit weak, correlation between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and body mass index (BMI). This seemingly counterintuitive result could be explained by several factors. The PREDIMED score, while validated for assessing Mediterranean diet adherence, may not fully capture the quantitative aspects of food consumption or other lifestyle factors that influence BMI. Additionally, it is possible that subjects with a higher BMI have already undertaken lifestyle modifications, including the adoption of healthier eating patterns, as a response to their condition. However, the cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow causal relationships to be established.

Strengths and Limitations

Our recruitment strategy through preventive health visits, while systematic, may have introduced selection bias: our sample of students belonging to health-related degree programs might represent a more health-conscious subset of the student population. Additionally, while participation was voluntary, those who chose to participate might have been more interested in health-related behaviors, potentially leading to self-selection bias. However, our achieved sample size (242) exceeded the minimum required sample size (174) calculated through G*Power analysis (α = 0.05, power = 0.80, medium effect size = 0.25), suggesting adequate statistical power for our analyses.

The use of self-administered questionnaires to assess eating habits and physical activity may be subject to bias; the PREDIMED questionnaire, while a validated instrument, focuses on frequency of food consumption rather than actual quantities, limiting the ability to assess total caloric intake. Another limitation concerns the PREDIMED questionnaire’s score regarding wine consumption, as future studies might benefit from modified scoring systems that better align with contemporary public health recommendations. Furthermore, although possible causal relationships between the variables are suggested, the cross-sectional design used does not allow for causal inferences to be drawn. Despite these limitations, the results provide important insights into health promotion for the University of Campania peer group. In particular, the following recommendations emerge: it would be necessary to implement specific nutrition education programs for different professional groups, with particular attention to nursing students. These programs should focus not only on the transmission of theoretical knowledge but also on the development of practical skills for the adoption of proper Mediterranean alimentation. In addition, physical activity promotion interventions should be differentiated according to gender and occupational group. Particular attention should be paid to reducing sedentary behavior during working hours.