Use of Fly Ash Layer as a Barrier to Prevent Contamination of Rainwater by Contact with Hg-Contaminated Debris

Abstract

1. Introduction

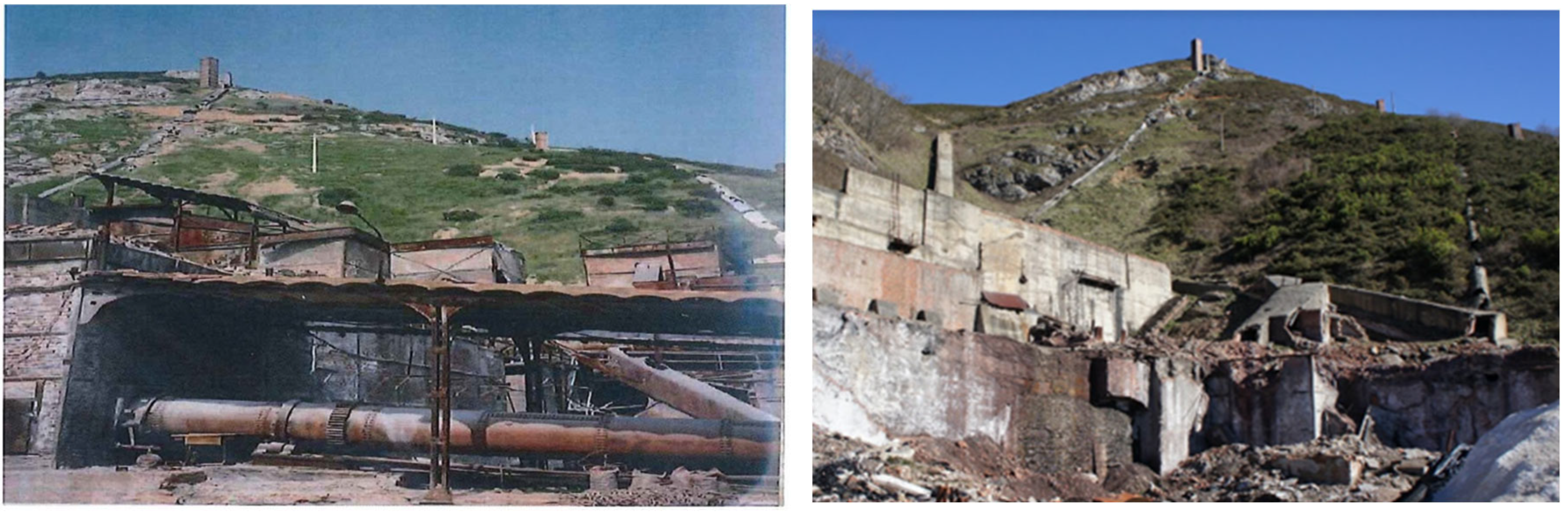

2. Site Description and Rainwater Contamination

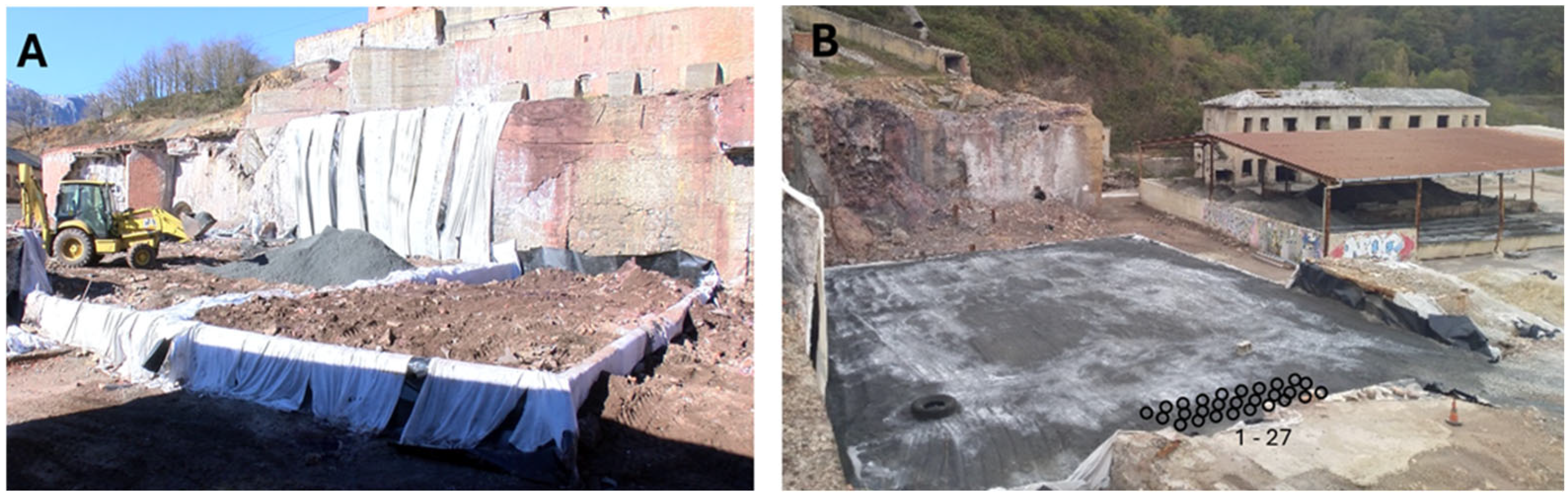

2.1. Abandoned Mercury Mining Facilities

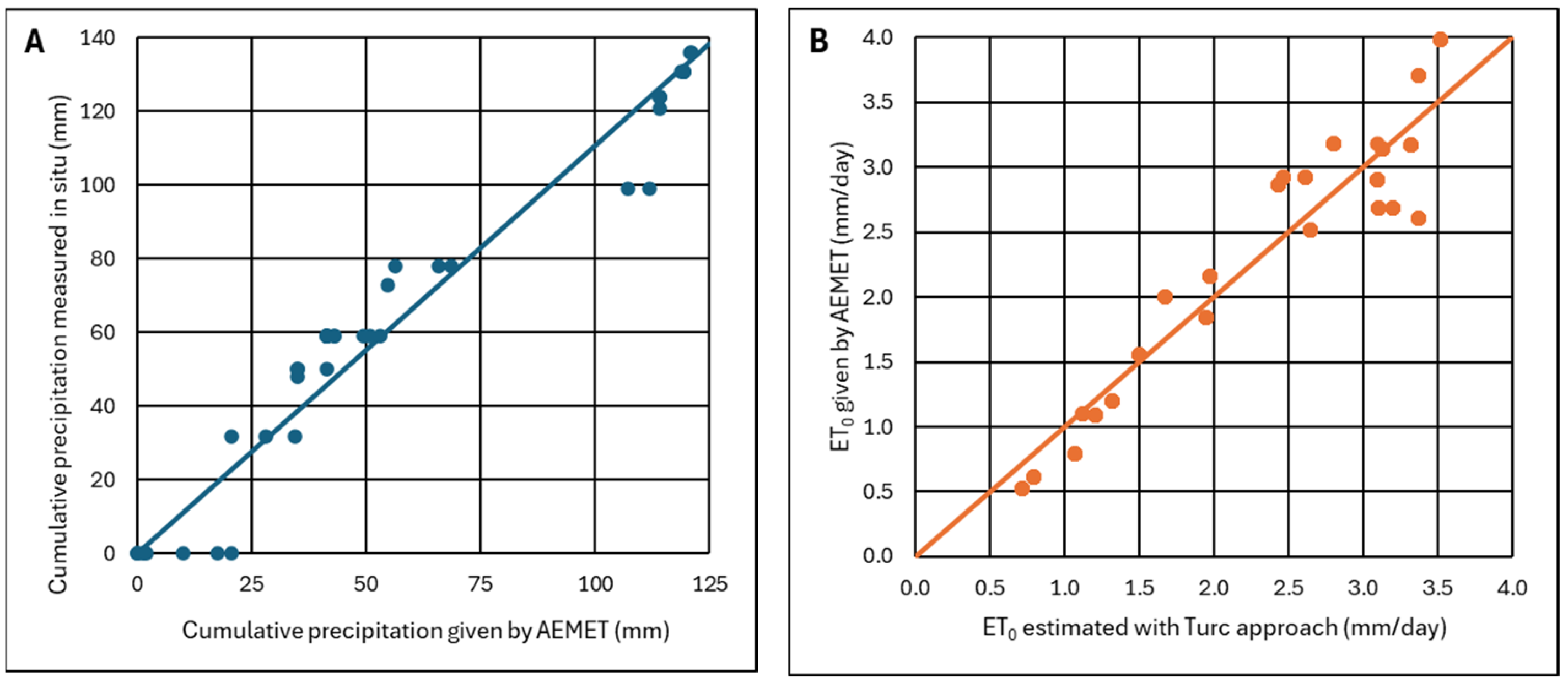

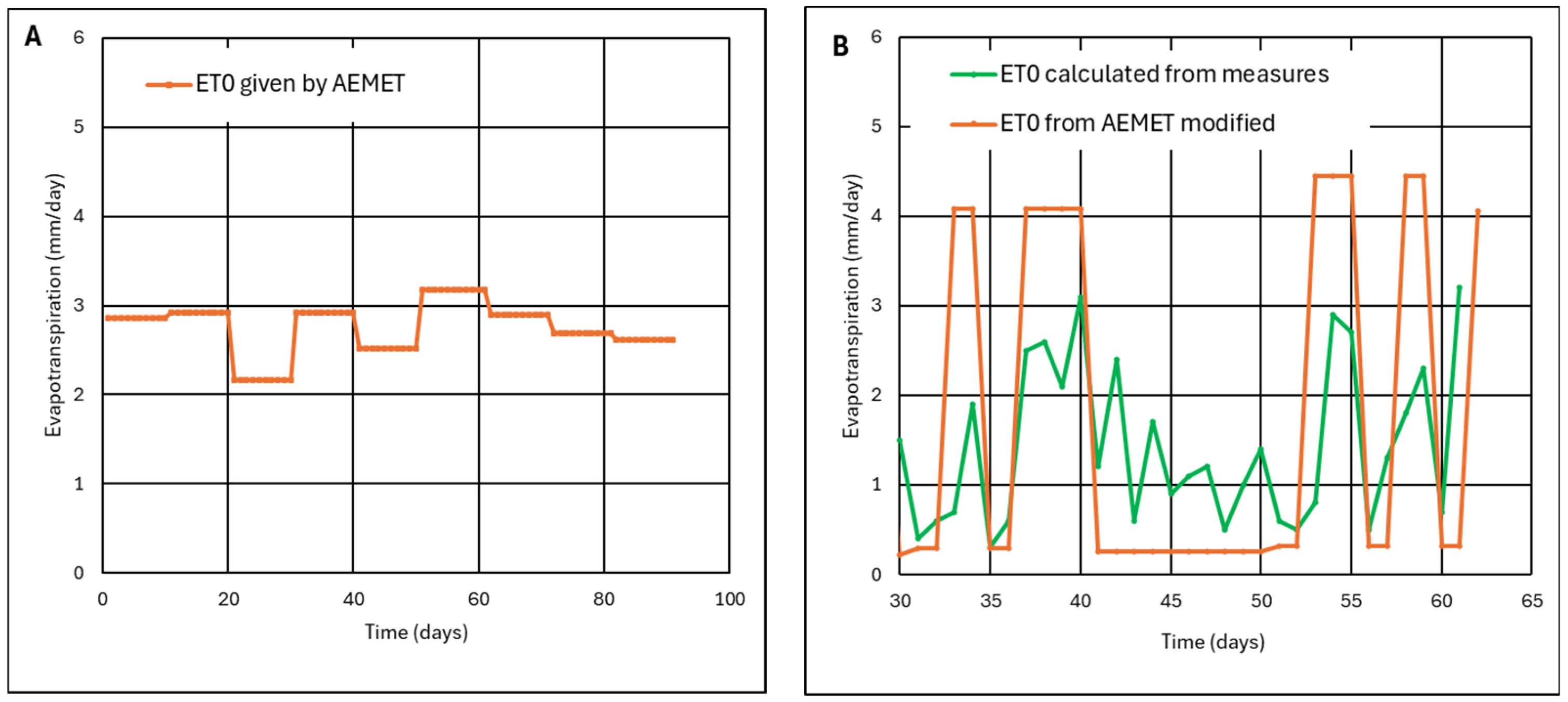

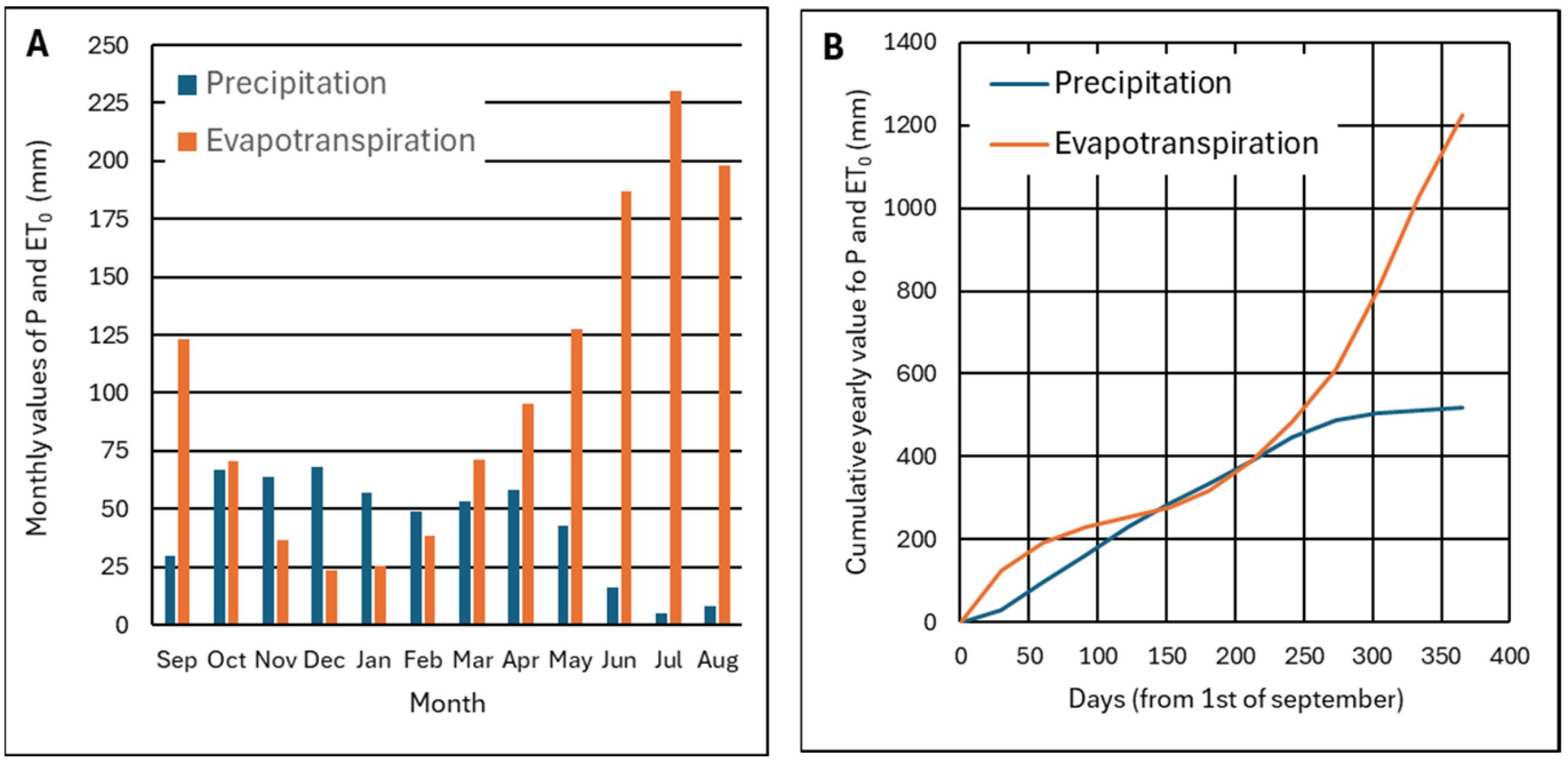

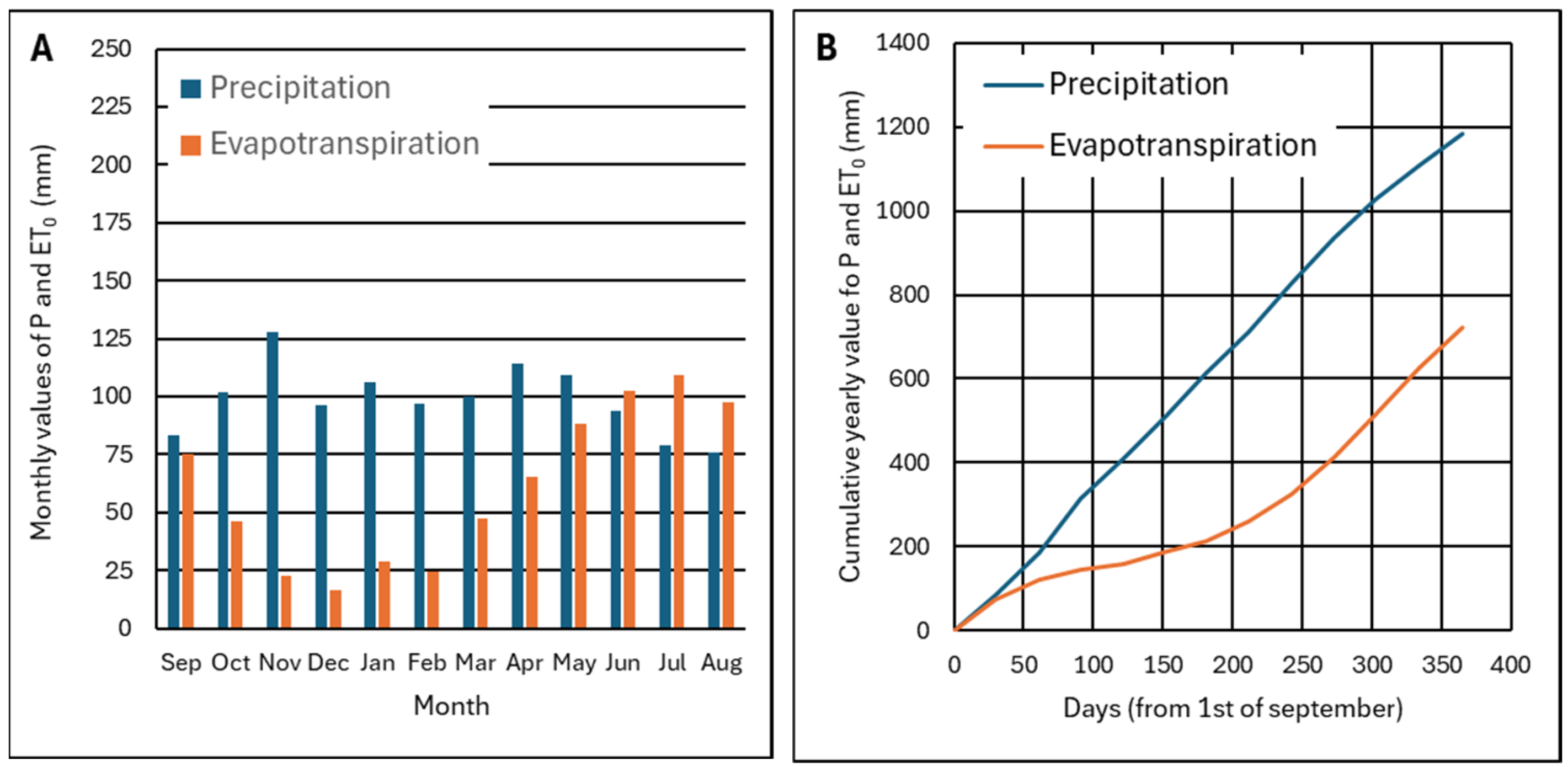

2.2. Precipitation and Evapotranspiration in the Study Area

2.3. Rainwater Contamination

3. Materials and Methods

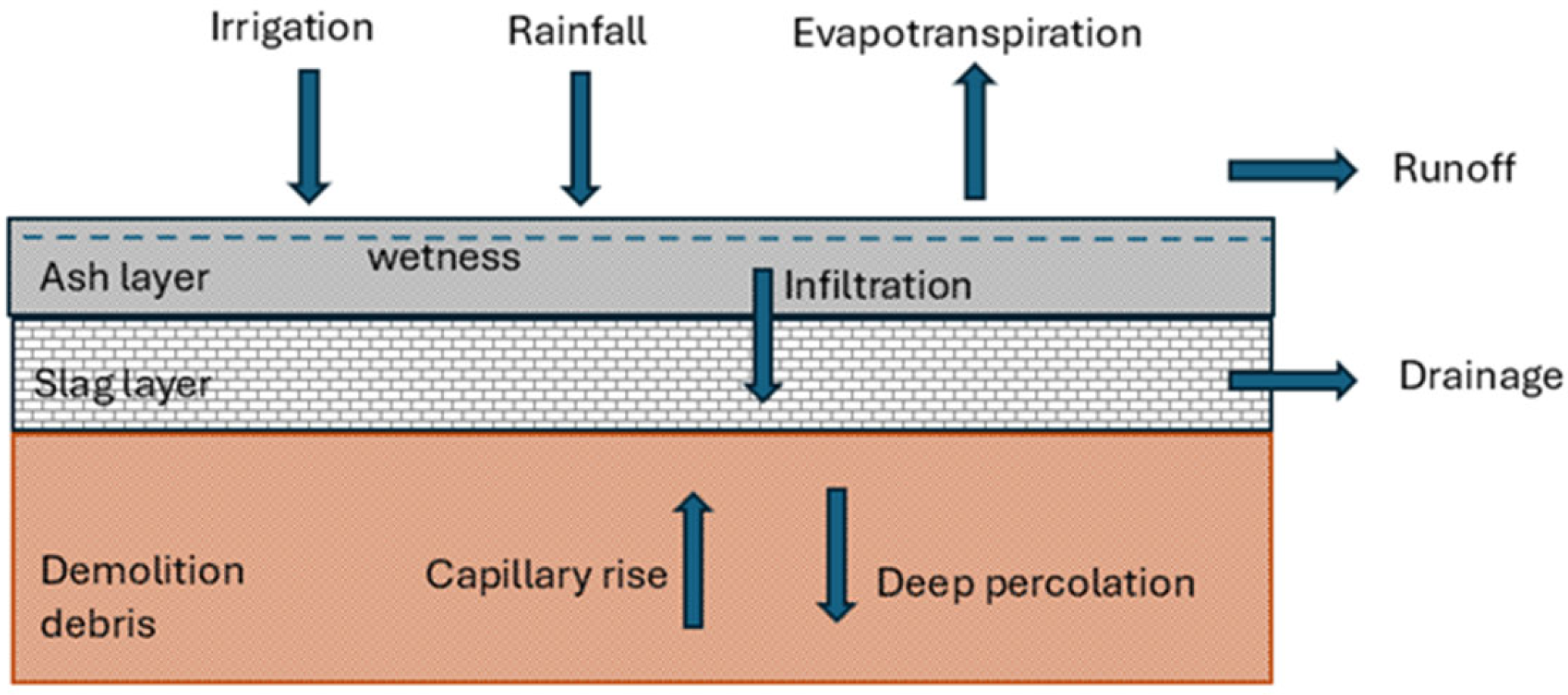

3.1. Water Balance

3.2. Tests’ Description

3.2.1. Laboratory Tests

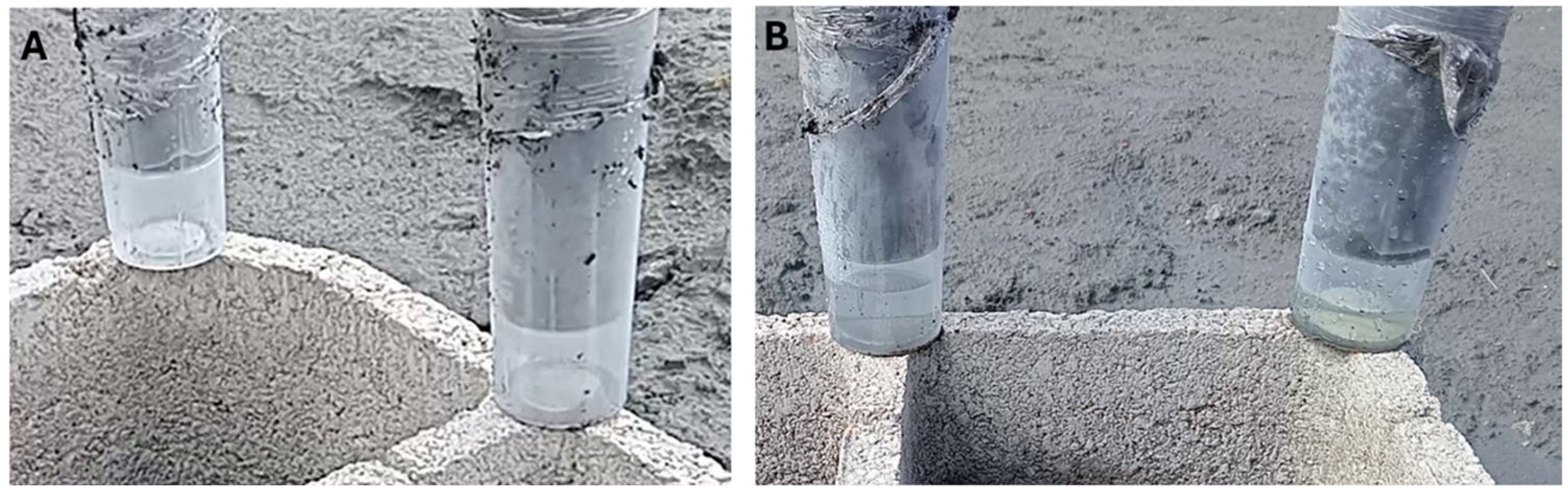

3.2.2. Full-Scale Tests in the Abandoned Mine Facilities

- Summary of precipitation, temperature, etc., hour by hour.

- Summary of precipitations, temperatures, etc., of the previous days.

4. Results

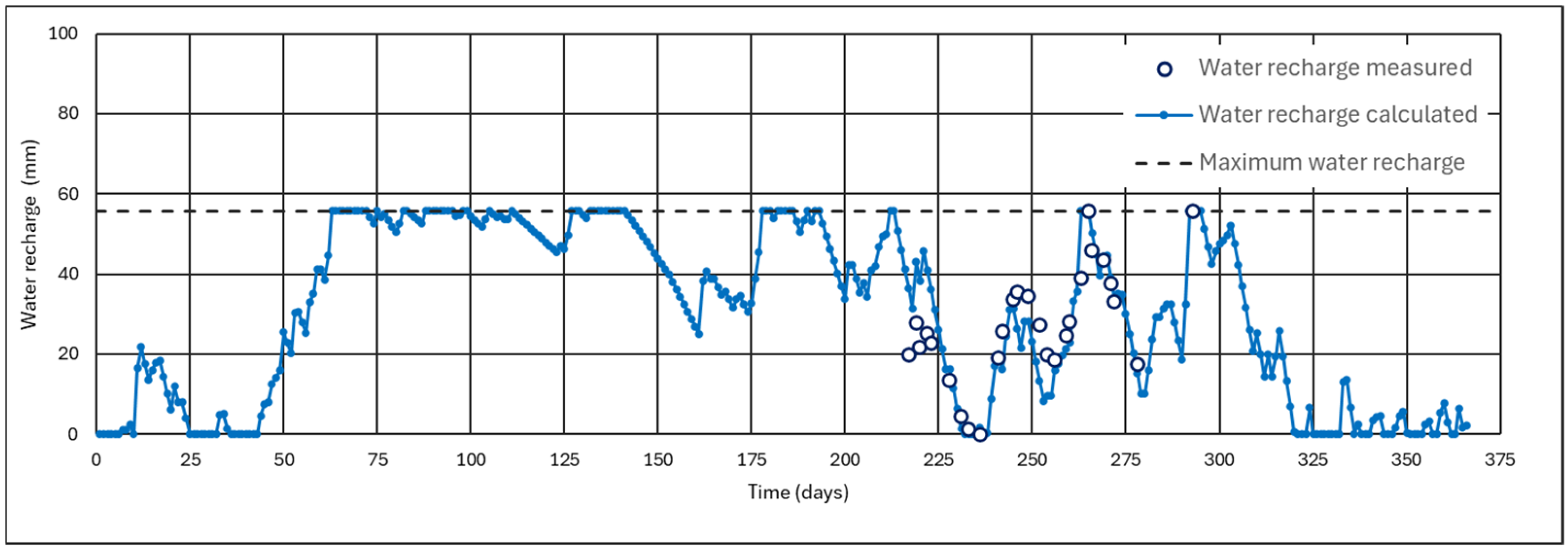

4.1. Results of the Tests in the Contaminated Debris Treatment Cell

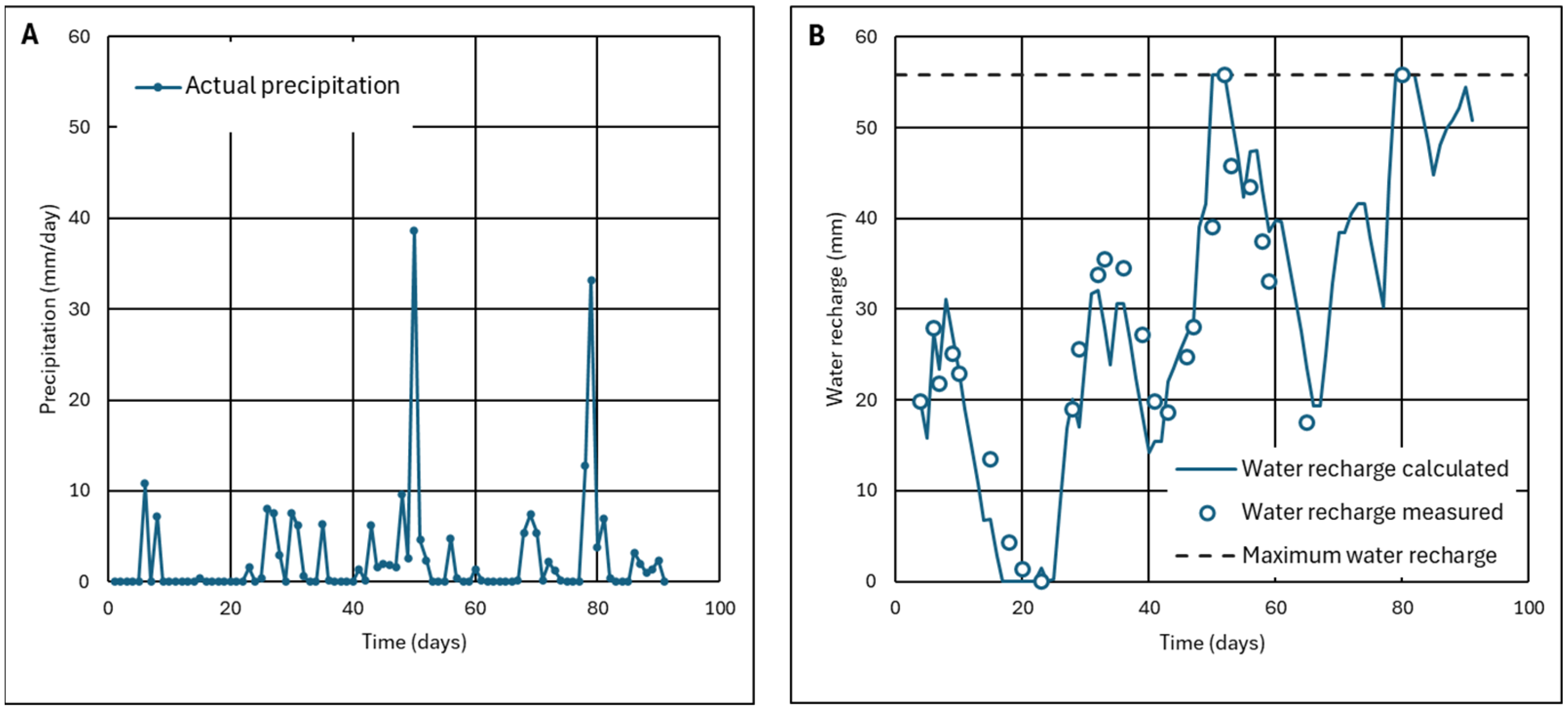

4.1.1. Results of the Monitoring of Ash Wetness for Three Months

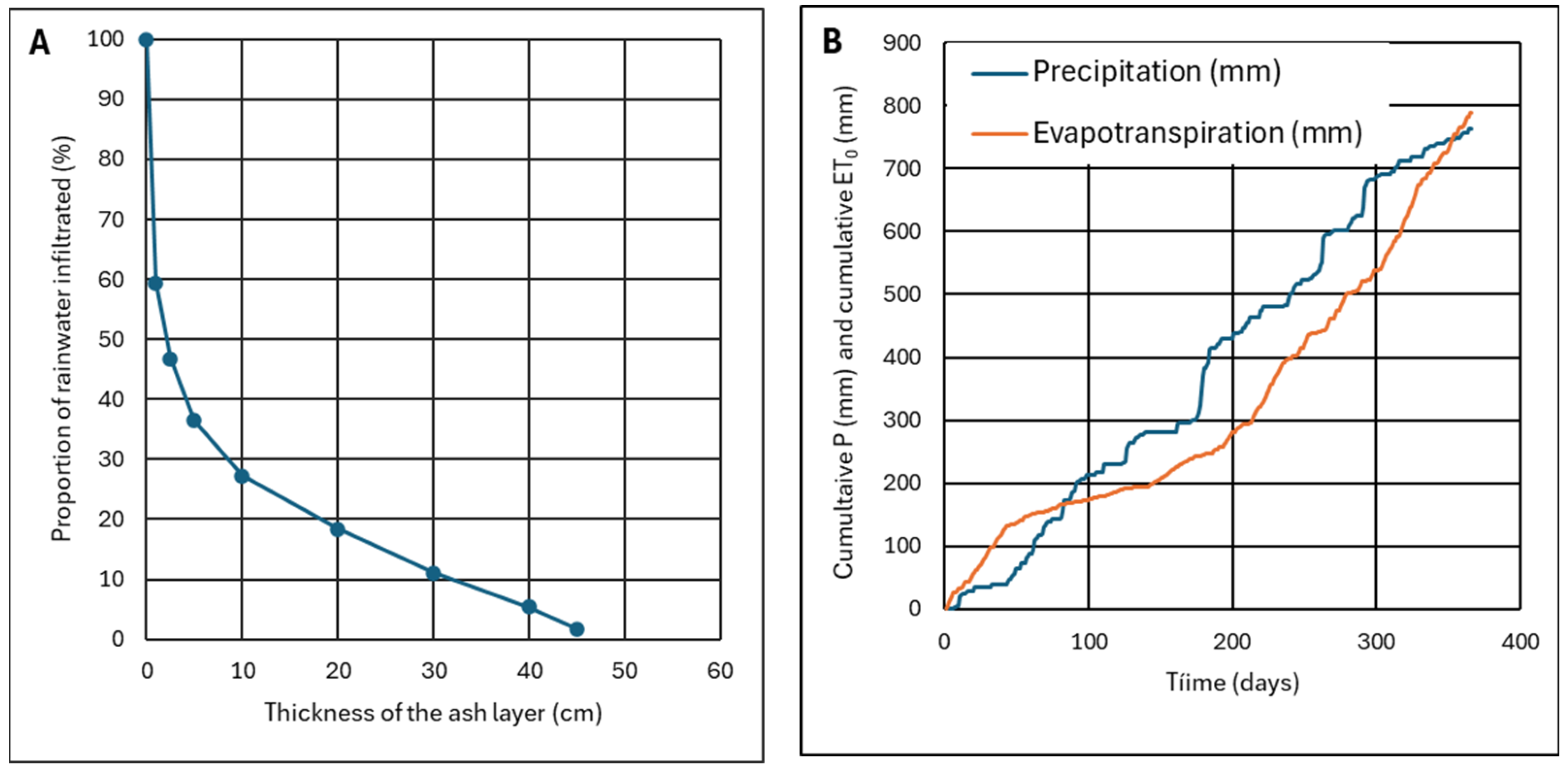

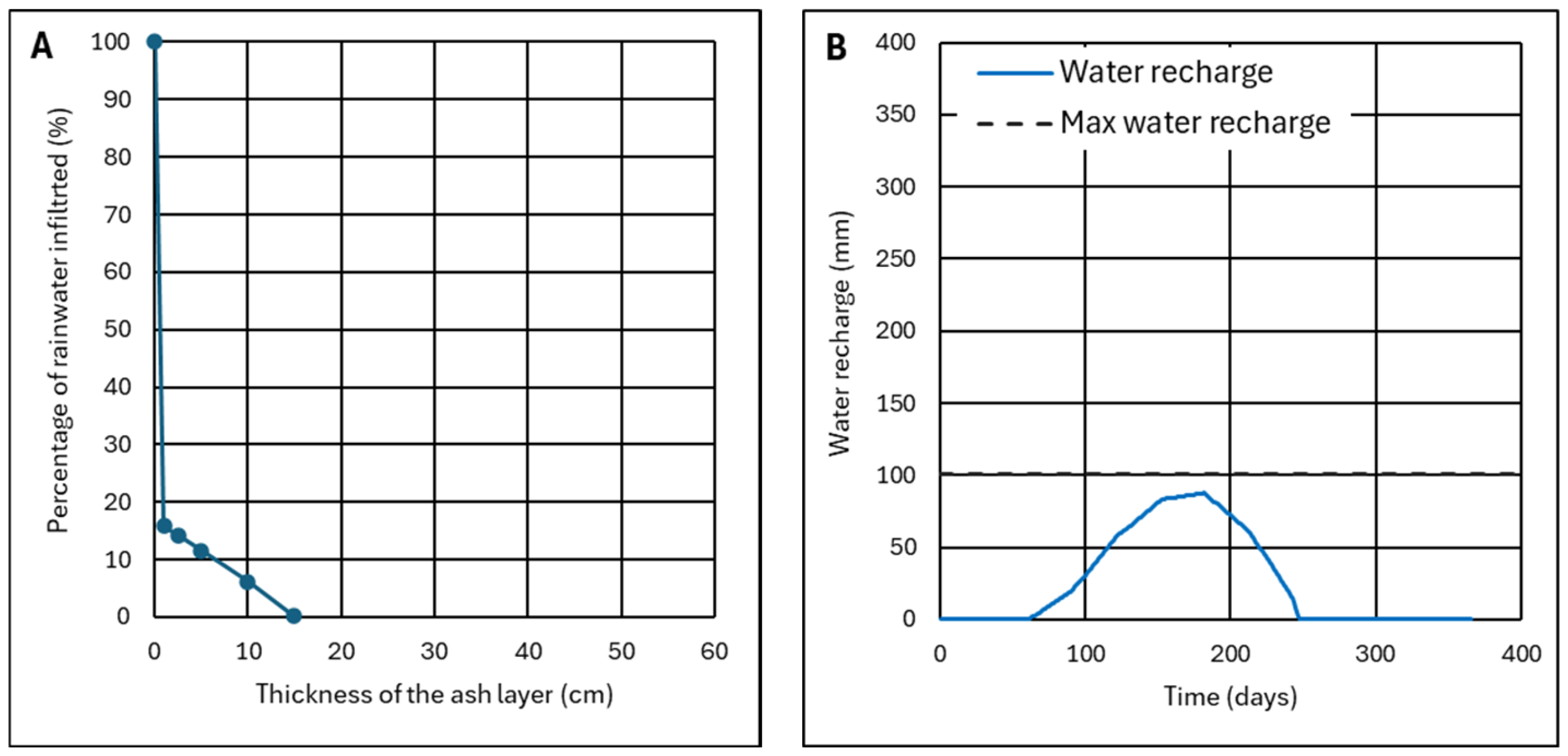

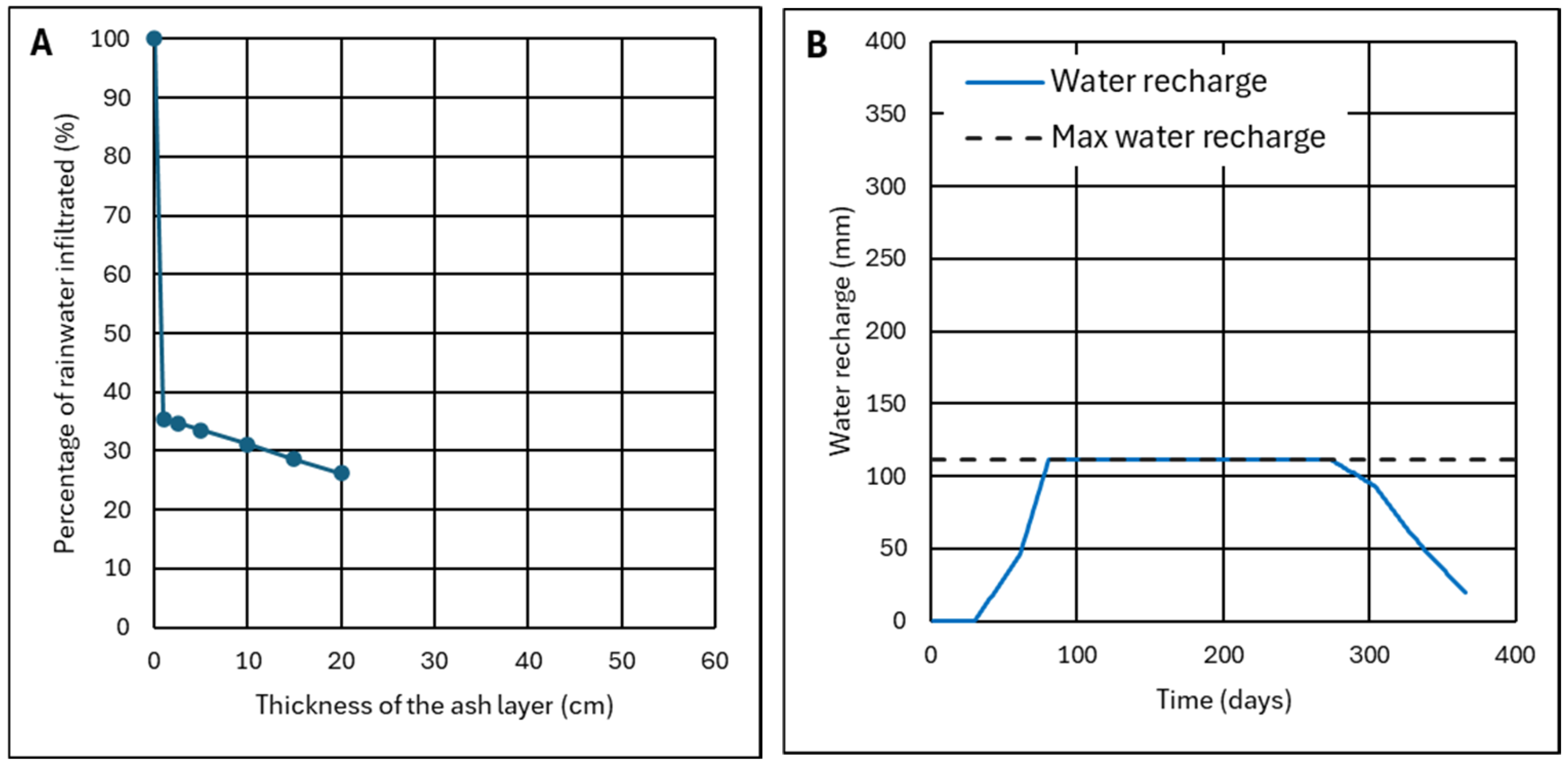

4.1.2. Effect of the Thickness of the Ash Layer

- The ash layer must be thick enough so that the recharge does not reach the maximum recharge, which is the limit for start infiltration.

- The recharge, at the end of a hydrological year, must be zero or have the same value as at the beginning of this year.

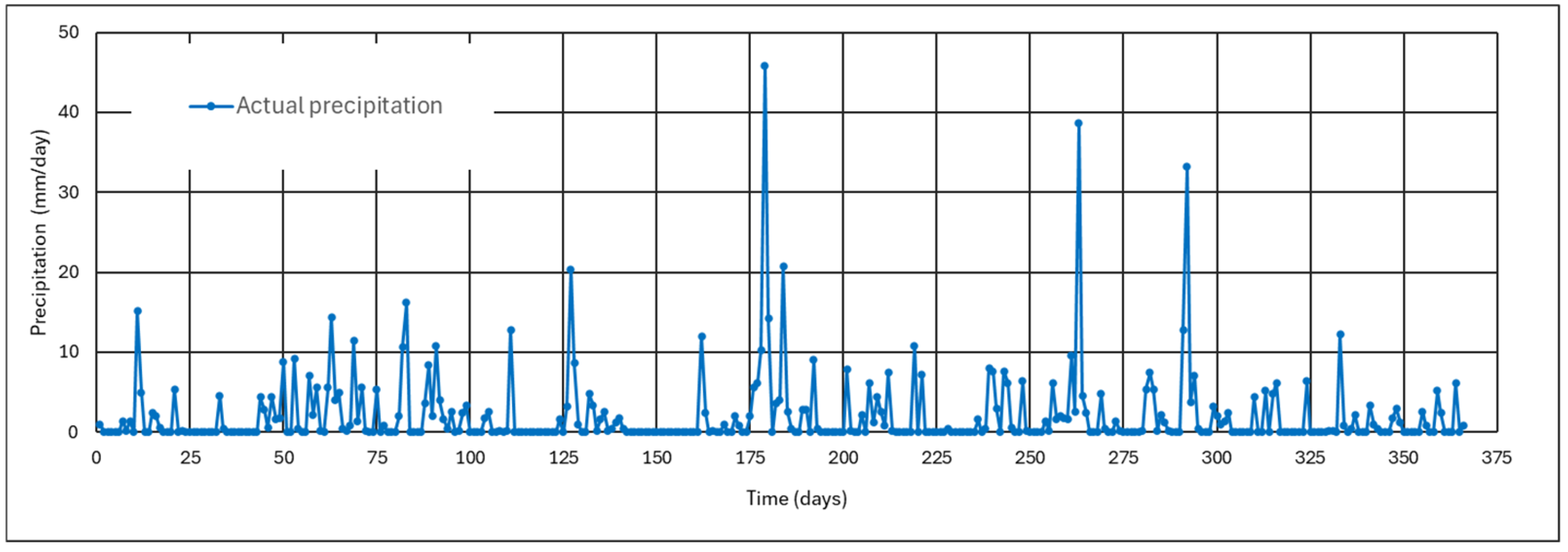

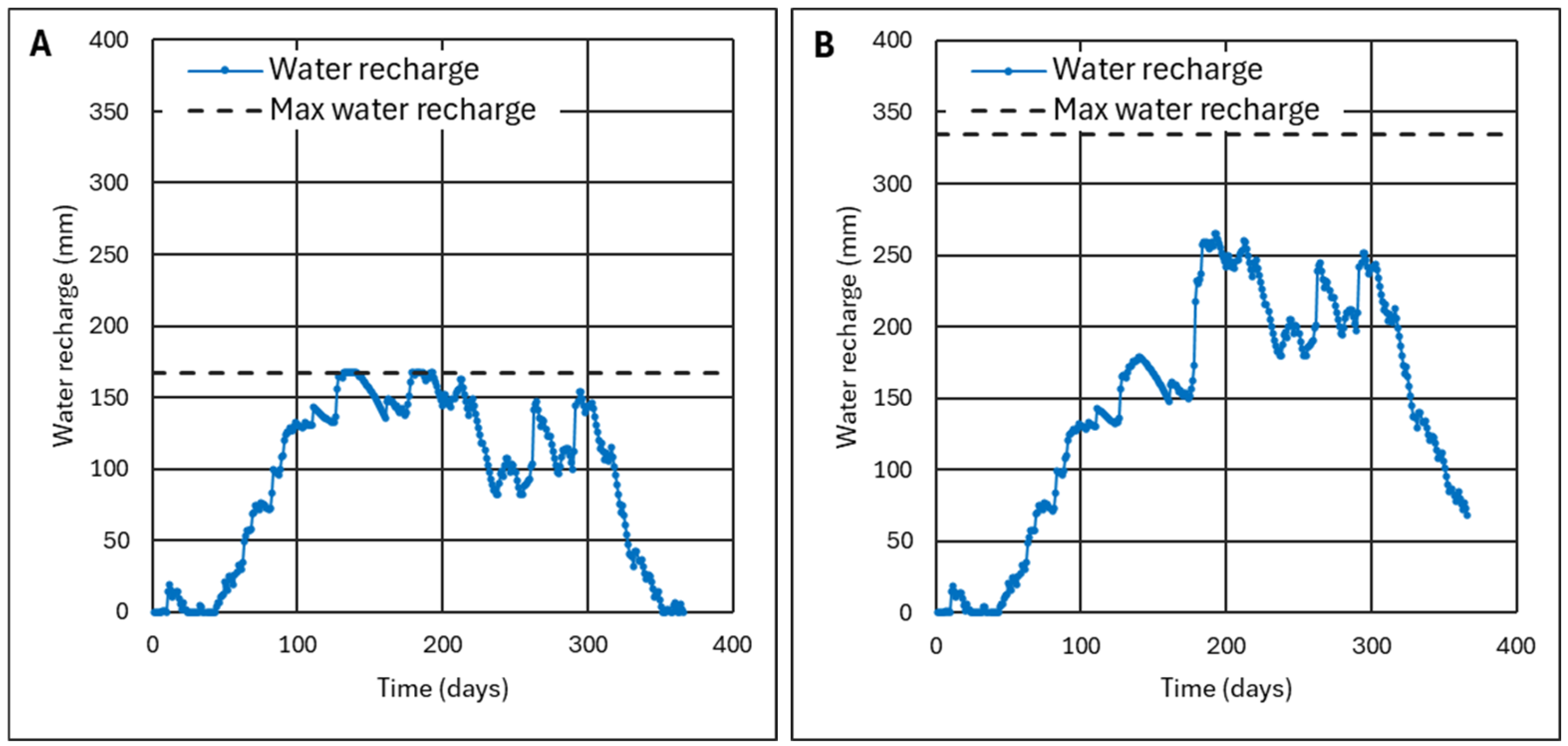

4.2. Analysis of Other Areas with Different Climatology

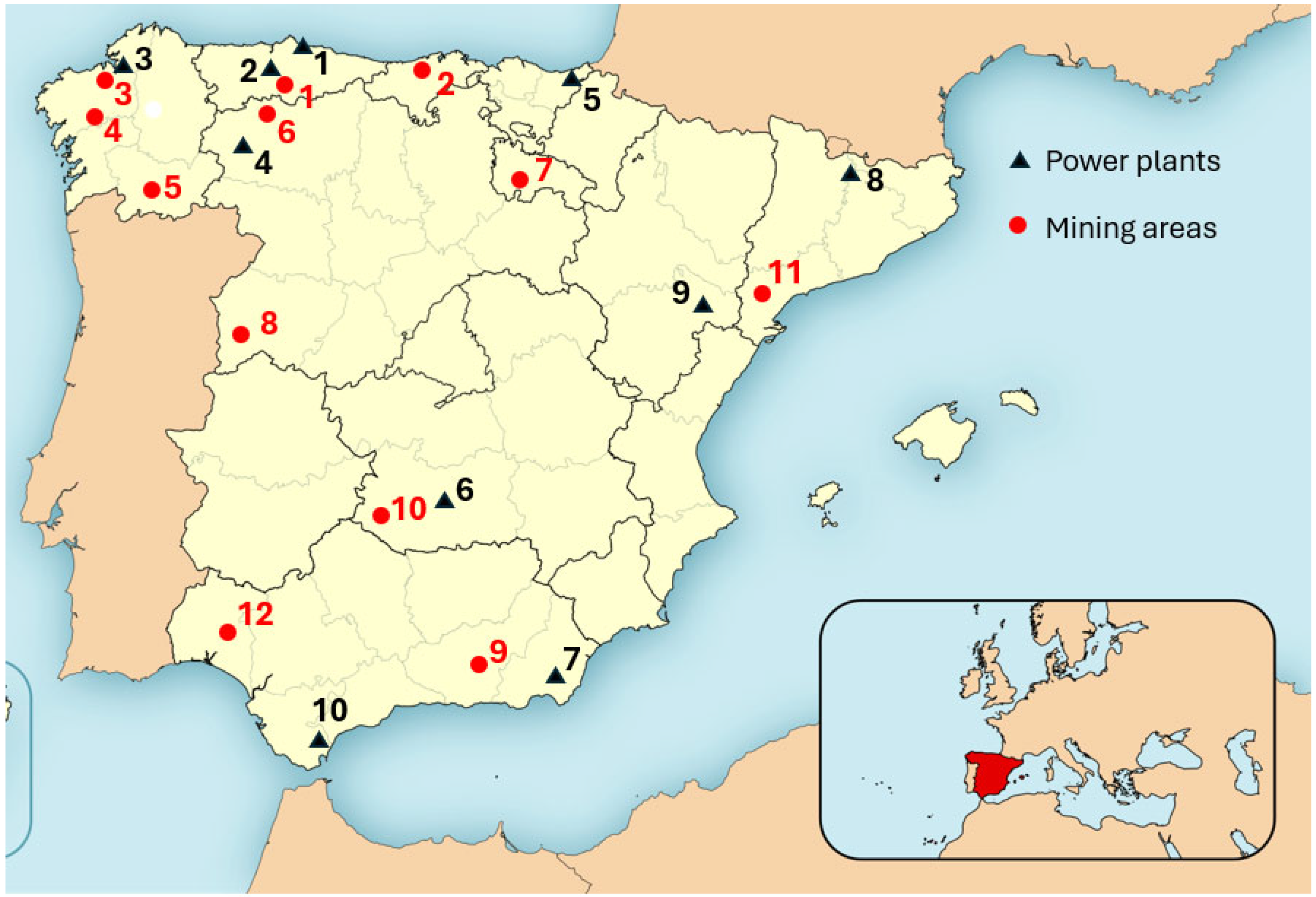

4.2.1. Selection of the Mining Areas

- There has been metal mining in the past and there may be abandoned waste dumps that need to be restored.

- There could be future mining projects driven by the existence of strategic raw materials.

- They are less than 500 km from a thermal power plant (in operation or closed) with an ash dump.

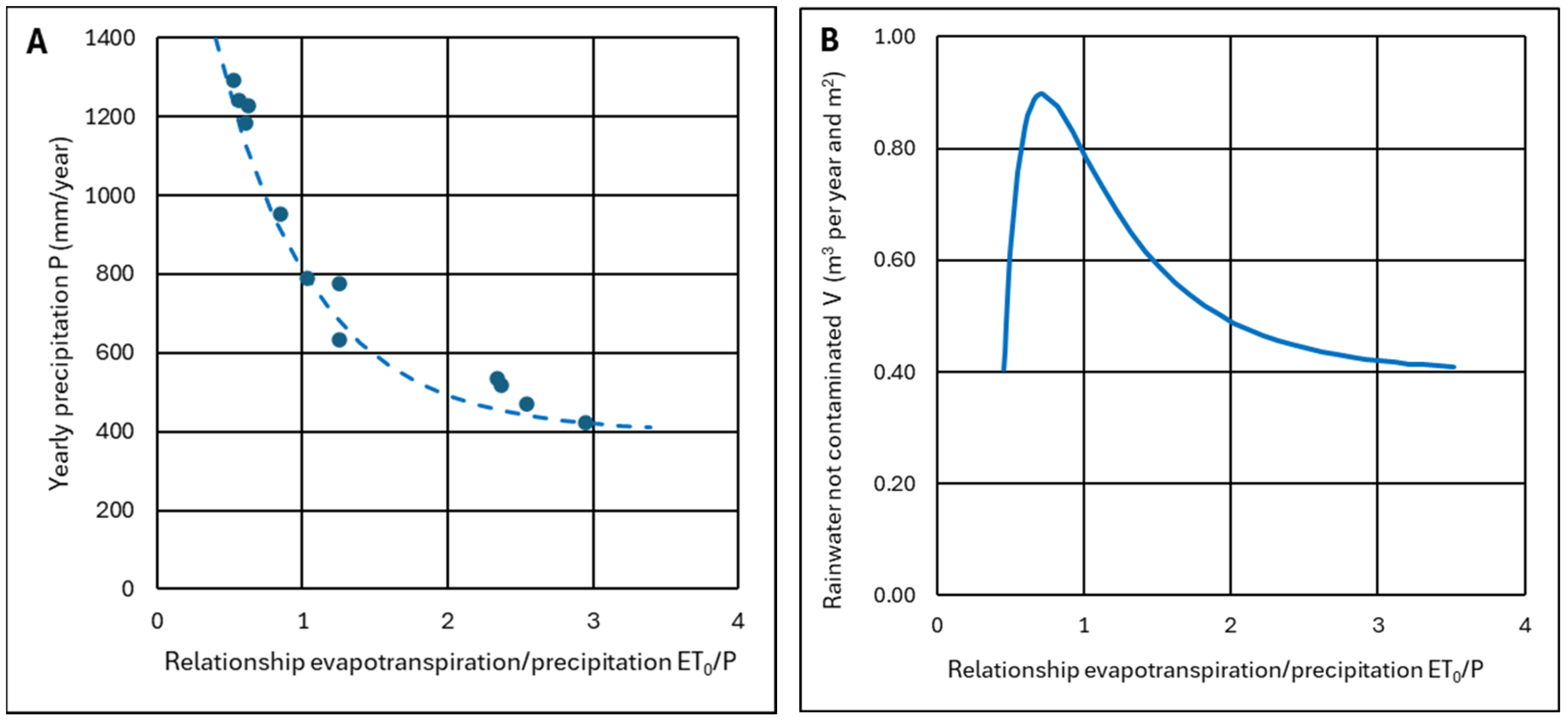

- They have different climatic conditions from each other, with the evapotranspiration to precipitation ratio ET0/P varying between 0.5 and 3.0.

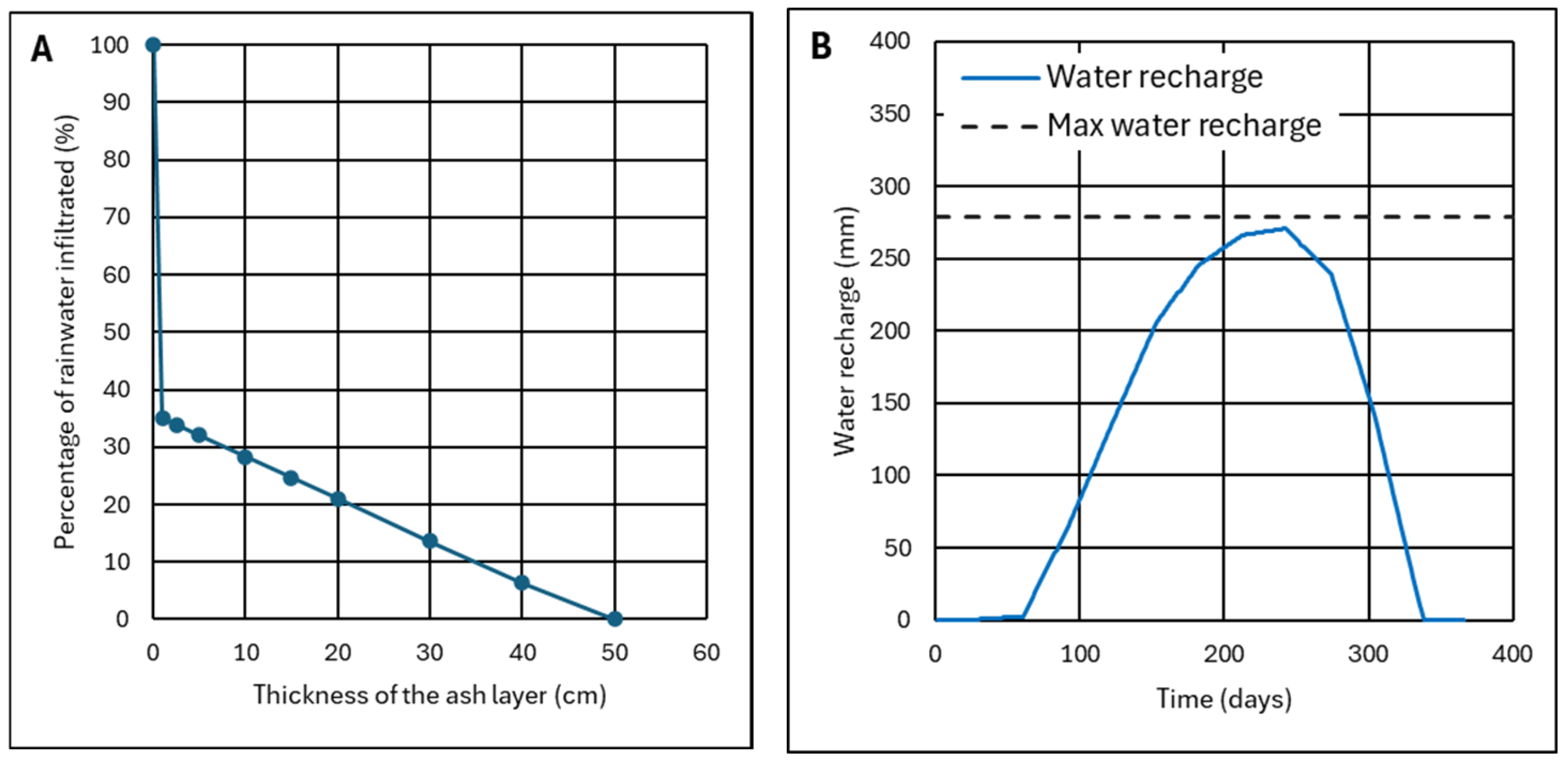

4.2.2. Analysis of Three Representative Cases

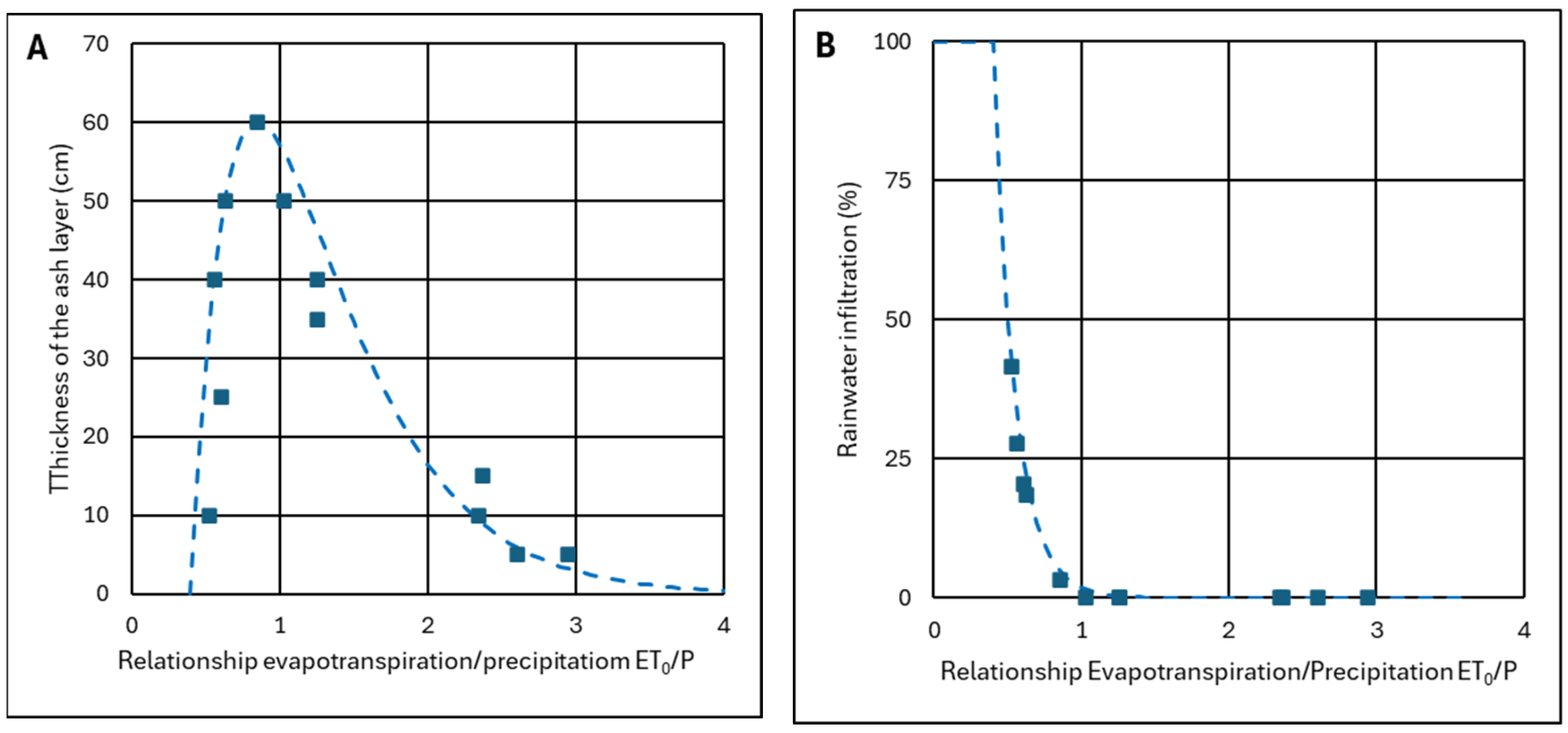

4.2.3. Criterion to Determine the Ash Layer Thickness for Minimum Infiltration

- For ET0/P ≥ 1, ash can be used as a barrier layer, achieving zero infiltration or waterproofing if the ash layer is thick enough; for values of ET0/P ≈ 1, thicknesses of h = 50–60 cm will be necessary, which are drastically reduced to h = 10–15 cm when ET0/P ≥ 2. This ensures that water will not pass through the ash layer because it has sufficient maximum recharge to absorb excess water during rainy seasons. Theoretically, the ash layer could replace a layer of clay or a layer of clay plus a HDPE sheet.

- For ET0/P < 1, the ash layer can no longer be considered impermeable. With values of ET0/P ≈ 0.7, a layer of 40–50 cm can be used to stop more than 80% of rainwater. However, a HDPE waterproofing sheet may be required. With ET0/P ≈ 0.5 values, the worst conditions, it does not make sense for the ash layer to be very thick because it becomes totally saturated and does not have time to dry; however, the ash layer can still be useful since a thickness of only 10–15 cm allows less than 50% of the rainwater to pass through.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- The effect is permanent over time as it is based on a physical barrier effect.

- The contamination reduction is independent of the initial concentration.

- The contamination reduction is for any PTE (Hg, Pb, Zn, etc.).

- Not trying to achieve absolute waterproofing based only on a very low hydraulic conductivity.

- Using by-products such as fly ash, with sufficiently low hydraulic conductivity and sufficiently high porosity, with sufficient recharge capacity to facilitate evapotranspiration and reduce water infiltration as far as possible.

- Prevent the rainwater from being contaminated is always a good result and, even if 100% waterproofing is not achieved, it can be a successful result in many cases.

- Reducing the volume of contaminated water results in economic savings because treatments for eliminating PTEs of the contaminated water are usually expensive.

- The leachate contamination reduction, due to the dilution in the water of the rivers, greatly reduces the extent of contamination so that the maximum concentration levels are closer to the source of contamination.

- The recharge is sufficiently large to absorb the maximum difference between precipitation and evapotranspiration.

- Infiltration is theoretically null or as little as possible.

- The recharge balances evapotranspiration in the dry season, ensuring that the planted species always have moisture.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Model of the Water Balance

Appendix A.1. Infiltration and Evaporation Models

Appendix A.1.1. Infiltration and Evaporation Analytical Models

Appendix A.1.2. Empirical Evapotranspiration Models

Appendix A.2. Water Balance

Appendix A.2.1. Hypothesis and Basic Formulae

- The test is performed in a treatment cell with a waterproofing sheet on the walls and floor; therefore, water can only enter the cell from the top surface. The capillary rise and deep percolation components are null.

- Water can only exit the cell either by evaporating or through a drain that exists in the slag layer just below the ash; there are no plants and then there is no transpiration, and no drainage was observed.

- The only water supply from outside the cell is rainwater; there is no irrigation.

- The treatment cell is horizontal, so there is no horizontal water flow; water can only ascend/descend or evaporate.

- It is tested on an ash layer of thickness h; for it to become saturated with rainfall, a small area of ash layer is prepared by reducing its thickness to h = 10 cm.

- The rainwater evaporates or passes into the ashes, increasing their humidity. As long as a maximum degree of humidity is not reached, the water not evaporated remains retained in the ash layer.

- The water begins to infiltrate into the lower layer of slag as soon as the ashes are saturated with water, acting as a drainage layer.

- There are no plants, so there is no elimination of water by transpiration; it is only by direct evaporation.

- Capillarity does not enter directly into the calculations.

- It is assumed that the behavior described by the model is valid for an ash layer up to h ≈ 50–60 cm.

- (1)

- In the first scenario, precipitation of the analyzed day is less than potential evapotranspiration (Pi ≤ ETPi), but there is sufficient water recharge for all that evapotranspiration to occur (Pi + Ri-1 ≥ ETPi). Actual evapotranspiration, ETRi, will be equal to potential evapotranspiration, ETPi, since there is enough water. Recharge is increased by precipitation, but decreased by evapotranspiration (Equations (A1)–(A4)).

- (2)

- Scenario typical of very dry periods. Precipitation is less than potential evapotranspiration (Pi ≤ ETPi) and there is not enough recharge to produce all that possible evapotranspiration (Pi + Ri-1 < ETPi). The actual evapotranspiration ETRi will equal rainfall and whatever water remains in the recharge. Recharge is increased by precipitation, but recharge is depleted due to evaporation being so intense (Equations (A5)–(A8)).

- (3)

- The third scenario is typical of humid periods, in which precipitation is higher than evapotranspiration (Pi > ETPi), leading to increased recharge, but without reaching the state of soil saturation and without reaching the maximum moisture that the soil can store (Ri ≤ Rmax). The part of rainfall that does not evaporate increases soil water recharge (Equations (A9)–(A12)) is as follows:

- (4)

- The fourth scenario occurs in rainy periods (Pi > ETPi). After several days of rainfall, the maximum recharge (Ri > Rmax) is reached and water begins to percolate or infiltrate to the lower layers (Ii > 0). However, the precipitation intensity does not reach a minimum value (Pi ≤ PN) for runoff to occur (Equations (A13)–(A18)).

- (5)

- The fifth scenario occurs in times of continuous rainfall (Pi > ETPi), with days of very heavy rainfall, above a minimum value (Pi > PN), which causes runoff (Ei > 0), because the 1 h rainwater flow (I1) is greater than the maximum possible infiltration through the water-saturated ash (I1 > Imax) (Equations (A19)–(A26)).

Appendix A.2.2. Precipitation and Evapotranspiration

Appendix A.2.3. Maximum Water Recharge

Appendix A.2.4. Maximum Water Infiltration

- The piezometric level h is equal to the thickness of the ash layer, since the rainfall is not considered to accumulate on the ash and the bottom layer is a draining layer.

- Since the flow is vertical, the distance to be traveled by the water is equal to the thickness of the ash layer x = h.

Appendix A.2.5. Runoff Condition

| 26 February 2024 | P24max (mm/day) | 45.80 |

| I24 (mm/h) | 1.91 | |

| 20 May 2024 | P1max (mm/h) | 25.60 |

| I1 (mm/h) | 25.60 | |

| 20 May 2024 | P6max (mm/6 h) | 37.00 |

| I6 (mm/h) | 6.17 | |

| n24-1 | 0.82 | |

| n24-6 | 0.85 | |

| n6-1 | 0.79 | |

| n | 0.82 |

References

- Giusti, L. A Review of Waste Management Practices and Their Impact on Human Health. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 2227–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asokan, P.; Saxena, M.; Asolekar, S.R. Coal Combustion Residues—Environmental Implications and Recycling Potentials. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2005, 43, 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbitt, C.W.; Lindner, A.S. A life cycle comparison of disposal and beneficial use of coal combustion products in Florida. Part 1: Methodology and input and emissions inventory. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2008, 13, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, I.; Hughes, R.E.; DeMaris, P.J. Formation and Use of Coal Combustion Residues from Three Types of Power Plants Burning Illinois Coals. Fuel 2001, 80, 1659–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodella, N.; Pasquali, M.; Zacco, A.; Bilo, F.; Borgese, L.; Bontempi, N.; Tomasoni, G.; Depero, L.E.; Bontempi, E. Beyond waste: New sustainable fillers from fly ashes stabilization, obtained by low cost raw materials. Heliyon 2016, 2, e00163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, Z.; Komorek, J.; Białecka, B.; Nowak, J.; Klupa, A. Assessment of the potential of polish fly ashes as a source of rare earth elements. Ore Geol. Rev. 2020, 124, 103638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmaruzzaman, M. A review on the utilization of fly ash. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2010, 36, 327–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbitt, C.W.; Lindner, A.S. A Life Cycle Inventory of Coal Used for Electricity Production in Florida. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward-Clyde Consultants Report on Combustion By-Products in Florida; Provided courtesy of the Florida Electric Utility Coordinating Group: Tallahassee, FL, USA, 1994.

- Zhao, Y.P.; Zhao, L.; Feng, L.; Yang, Y. Hazardous Contaminants in the Environment and Their Laccase-Assisted Degradation—A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 234, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, V.M. Durability of concrete incorporating high-volume of lowcalcium (ASTM Class F) fly ash. Cem. Concr. Compos. 1990, 12, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.F.; Luna, Y.; Querol, X.; Antenucci, D.; Vale, J. Waste stabilization/solidification of an electric arc furnace dust using fly ash-based geopolymers. Fuel 2009, 88, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolev, K.; Vivian, I.F.; Saha, R.; Wasiuddin, N.M.; Saltibus, N.E. The effect of fly ash on the rheological properties of bituminous materials. Fuel 2014, 116, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, E.R.; Mateus, R.; Cames, A.F.; Bragana, L.; Branco, F.G. Comparative environmental life-cycle analysis of concretes using biomass and coal fly ashes as partial cement replacement material. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2221–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embong, R.; Kusbiantoro, A.; Shafiq, N.; Nuruddin, M.F. Strength and microstructural properties of fly ash based geopolymer concrete containing highcalcium and water-absorptive aggregate. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Liu, H.; Chen, C.; Li, J.; Hou, H.; Hewage, K.; Sadiq, R. An integrated geospatial correlation analysis and human health risk assessment approach for investigating abandoned industrial sites. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 293, 112891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlongo, S.E. Physical hazards of abandoned mines: A review of cases from South Africa. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2023, 15, 101285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Fernández, L.; Rodríguez, P.; Martínez-Madrid, M. Sediment Toxicity and Bioaccumulation Assessment in Abandoned Copper and Mercury Mining Areas of the Nalón River Basin (Spain). Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2015, 68, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teunen, L.; Belpaire, C.; De Boeck, G.; Blust, R.; Bervoets, L. Mercury Accumulation in Muscle and Liver Tissue and Human Health Risk Assessment of Two Resident Freshwater Fish Species in Flanders (Belgium): A Multilocation Approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 7853–7865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilhos, Z.C.; Rodrigues-Filho, S.; Rodrigues, A.P.; Villas-Bôas, R.C.; Siegel, S.; Veiga, M.M.; Beinhoff, C. Mercury Contamination in Fish from Gold Mining Areas in Indonesia and Human Health Risk Assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 368, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Gao, J.; Pierce, E.; Strong, P.J.; Wang, H.; Liang, L. In Situ Remediation Technologies for Mercury-Contaminated Soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 8124–8147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hylander, L.D.; Meili, M. 500 Years of Mercury Production: Global Annual Inventory by Region until 2000 and Associated Emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 2003, 304, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Larssen, T.; Vogt, R.D.; Feng, X. Identification of Fractions of Mercury in Water, Soil and Sediment from a Typical Hg Mining Area in Wanshan, Guizhou Province, China. Appl. Geochem. 2010, 25, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, A.; Álvarez, R.; Charlesworth, S.; Miguel, E.D.; Loredo, J. Risk Assessment of Soils Contaminated by Mercury Mining, Northern Spain. J. Environ. Monit. 2011, 13, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Castro, I.; Molina, L.; Prieto-Fernández, M.A.; Segura, A. Past, present and future trends in the remediation of heavy metal contaminated soil—Remediation techniques applied in real soil-contamination events. Heliyon 2023, 9, 16692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hou, D.; Cao, Y.; Ok, Y.S.; Tack, F.M.G.; Rinklebe, J.; O’Connor, D. Remediation of Mercury Contaminated Soil, Water, and Air: A Review of Emerging Materials and Innovative Technologies. Environ. Int. 2020, 134, 105281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parameswaran, K. Sustainability considerations in innovative process development. In Innovative Process Development in Metallurgical Industry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 257–280. [Google Scholar]

- Santibánez, C.; Verdugo, C.; Ginocchio, R. Phytostabilization of copper mine tailings with biosolids: Implications for metal uptake and productivity of Lolium perenne. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 395, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, R.; Hernández, Z.; Fernández, B.; Bascompta, M. A Novel Solution to Avoid Mercury Emissions Produced by Highly Contaminated Demolition Debris in Mining Site. Environments 2023, 10, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazarra, A.; Flórez, E.; Peraza, B.; Tohá, T.; Lorenzo, B.; Criado, E.; Moreno, J.V.; Romero, R.; Bote, R. Mapas Climáticos de España (1981–2010) y ETo (1996–2016); Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica, Agencia Estatal de Meteorología: Madrid, Spain, 2018; p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- Sancho, J.M.; Riesgo, J.; Jiménez, C.; Sánchez, M.C.; Montero, J.; López, M. Atlas de Radiación Solar en España Utilizando Datos del SAF de Clima de EUMETSAT; Agencia Estatal de Meteorología (AEMET): Madrid, Spain, 2012; p. 162. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala, J.; Fernández, B. Industrial waste materials as adsorbents for the removal of As and other toxic elements from an abandoned mine spoil heap leachate: A case study in Asturias. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 384, 121446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Standards UNE EN 12457-4:2003; Characterisation of Waste: Leaching: Compliance Test for Leaching of Granular Waste Materials and Sludges—Part 4: One Stage Batch Test at a Liquid to Solid Ratio of 10 L/kg for Materials with Particle Size Below 10 mm (without or with Size Reduction). Asociación Española de Normalización: Madrid, Spain, 2003.

- Vaselli, O.; Nisi, B.; Rappuoli, D.; Cabassi, J.; Tassi, F. Gaseous Elemental Mercury and Total and Leached Mercury in Building Materials from the Former Hg-Mining Area of Abbadia San Salvatore (Central Italy). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Standards UNE-EN 1097-3:1999; Tests for Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates—Part 3: Determination of Loose Bulk Density and Voids. Asociación Española de Normalización: Madrid, Spain, 1999.

- European Standards UNE-EN 1097-6:2014; Tests for Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates—Part 6: Determination of Particle Density and Water Absorption. Asociación Española de Normalización: Madrid, Spain, 2014.

- European Standards UNE-EN 450-1:2013; Fly Ash for Concrete—Part 1: Definition, Specifications and Conformity Criteria. Asociación Española de Normalización: Madrid, Spain, 2013.

- European Standards UNE-EN ISO 17892-11:2020; Geotechnical Investigation and Testing - Laboratory Testing of Soil—Part 11: Permeability Tests (ISO 17892-11:2019). Asociación Española de Normalización: Madrid, Spain, 2020.

- CEDEX; Centro de Experimentación y Estudios de Obras Públicas. Ficha Técnica: Cenizas Volantes de Carbón y Cenizas de Hogar o Escorias; Ministerio de Fomento y Ministerio de Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- García-Fraile, J. Caracterización de Cenizas de Centrales Térmicas del Norte de España para su Aplicación en Usos Alternativos. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Oviedo, Oviedo, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Lue, H.; Zhu, Y.; Drake, S.; Liang, C. Long-term effects of revegetation on soil hydrological processes in vegetation-stabilized desert ecosystems. Hydrol. Process 2010, 24, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J.T. Direct hydraulic parameter and function estimation for diverse soil types under infiltration and evaporation. Transp. Porous Media 2017, 116, 797–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, W.Q.; Zou, X.Y.; Liu, J.J.; Zhang, M.Z.; Lü, W.; Gu, J. Effects of residual plastic film mixed in soil on water infiltration, evaporation and its uncertainty analysis. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2016, 32, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.C.; Li, X.Y.; Shi, H.B.; Zhang, D.L.; Xu, P.C. Effects of residual plastic film on infiltration and evaporation for sandy loam and sandy soil. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2017, 48, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Guo, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, T. Effects of enclosure measures on soil water infiltration and evaporation in arid and semi-arid grassland in northern China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1410037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiat, I.; Mackey, H.R.; Al-Ansari, T. A Review of Evapotranspiration Measurement Models, Techniques and Methods for Open and Closed Agricultural Field Applications. Water 2021, 13, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration: Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements—FAO Irrigation and Drainage; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, FAO: Rome, Italy, 1998; Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/x0490e/x0490e00.htm (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Neukum, C.; Morales-Santos, A.; Ronelngar, M.; Bala, A.; Vassolo, S. Modelling groundwater recharge, actual evaporation, and transpiration in semi-arid sites of the Lake Chad basin: The role of soil and vegetation in groundwater recharge Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 27, 3601–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornthwaite, C.W. An approach toward a rational classification of climate. Geogr. Rev. 1948, 38, 55–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turc, L. Estimation of irrigation water requirements, potential evapotranspiration: A simple climatic formula evolved up to date. Ann. Agron. 1961, 12, 13–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, G.H.; Samani, Z.A. Reference crop evapotranspiration from temperature. Appl. Eng. Agric. 1985, 1, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coly, O.; Weihermüller, L.; Ba, K.; Faye, S.C.; Faye, S.; Vereckeen, H. Estimation of Turc reference evapotranspiration with limited data against the Penman-Monteith Formula in Senegal. J. Agric. Environ. Int. Dev. 2016, 110, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, M.M. Formulas for rainfall intensities of long durations. Trans. ASCE 1932, 96, 592–624. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, V.T. Hydrologic Determination of Waterway Areas for Drainage Structures in Small Drainage Basins; Bulletin No. 462, Engineering. Experimental Station; University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign: Champaign, IL, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro, R.; Abarza, A.; Farías, C.; Jordán, C. Construcción de Curvas IDF (Intensidad-Duración-Frecuencia) en zonas semiáridas de Chile Central. In Proceedings of the Actas del XII Congreso Forestal Mundial, Quebec, QC, Canada, 21–28 September 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Moncho, R.; Belda, F.; Caselles, V. Climatic study of the exponent n of the IDF curves of the Iberian Peninsula. J. Weather Clim. West. Mediterr. 2009, 6, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Solid Sample | As (g/kg) | Hg (g/kg) | Leachate Sample | As (mg/L) | Hg (μg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 84.28 | 14.64 | 1 | 94.44 | 40.69 |

| 2 | 254.07 | 41.50 | 2 | 83.87 | 31.49 |

| 3 | 46.18 | 6.35 | 3 | 203.33 | 14.94 |

| 4 | 54.80 | 34.69 | 4 | 160.98 | 14.34 |

| 5 | 44.42 | 7.49 | 5 | 137.82 | 10.14 |

| 6 | 44.12 | 22.19 | 6 | 188.63 | 8.47 |

| 7 | 29.64 | 19.05 | 7 | 246.11 | 8.03 |

| 8 | 603.34 | 25.29 | 8 | 820.38 | 12.88 |

| 9 | 210.00 | 16.00 | 9 | 732.89 | 12.24 |

| 10 | 48.00 | 0.53 | 10 | 571.92 | 16.05 |

| 11 | 98.59 | 1.45 | 11 | 332.06 | 12.51 |

| N | 11 | 11 | N | 11 | 11 |

| Min | 29.64 | 0.53 | Min | 83.87 | 8.03 |

| Max | 603.34 | 41.50 | Max | 820.38 | 40.69 |

| Average | 136.13 | 17.20 | Average | 324.77 | 16.53 |

| SD | 172.07 | 13.17 | SD | 261.85 | 10.20 |

| SiO2 (wt%) | 61.7 | Hg (mg/kg) | 34,691 |

| Fe2O3 (wt%) | 7.1 | As (mg/kg) | 54,801 |

| MgO (wt%) | - | Zn (mg/kg) | 0.03 |

| K2O (wt%) | 0.8 | Cu (mg/kg) | 420 |

| Al2O3 (wt%) | 7.1 | Cr (mg/kg) | 920 |

| CaO (wt%) | 3.9 | Pb (mg/kg) | 3400 |

| SO3 (wt%) | 7.2 | Ni (mg/kg) | 0.02 |

| TiO2 (wt%) | 0.55 | Cd (mg/kg) | 0.01 |

| MnO (wt%) | 0.02 | pH | 5.1 |

| SiO2 (wt%) | 56.5 | Hg (mg/kg) | 2 |

| Fe2O3 (wt%) | 9.5 | As (mg/kg) | 59 |

| MgO (wt%) | 0.9 | Zn (mg/kg) | 90 |

| K2O (wt%) | 2.61 | Cu (mg/kg) | 57 |

| Al2O3 (wt%) | 23.9 | Cr (mg/kg) | 83.6 |

| CaO (wt%) | 3.4 | Pb (mg/kg) | 16 |

| SO3 (wt%) | 2.04 | Ni (mg/kg) | 65.4 |

| TiO2 (wt%) | 0.85 | Cd (mg/kg) | 1.84 |

| MnO (wt%) | - | pH | 10.9 |

| Parameter | Value | Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Bulk density (g/cm3) | 0.96 | [35] |

| Actual particle density (g/cm3) | 2.38 | [36] |

| Moisture content of the ash in stockpile (% by weight) | 1.24 | [37] |

| Porosity (% by volume) | 58.8 | [35] |

| Hydraulic conductivity (m/s) | 2.83 × 10−6 | [38] |

| Zone | Mineral | Location | Province | Power Plant | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mercury | Mieres | Asturias | Soto de Ribera (2) | 15 km |

| 2 | Zinc | Torrelavega | Cantabria | Aboño (1) | 162 km |

| 3 | Wolframio | Santa Comba | La Coruña | Meirama (3) | 40 km |

| 4 | Copper | Santiago de Compostela | La Coruña | Meirama (3) | 55 km |

| 5 | Tin, Wolframio | Beariz | Orense | Compostilla (4) | 157 km |

| 6 | Iron | Villablino | León | Compostilla (4) | 62 km |

| 7 | Lead | Santa Engracia | La Rioja | Pasajes (5) | 190 km |

| 8 | Uranium | Ciudad Rodrigo | Salamanca | Puertollano (6) | 481 km |

| 9 | Iron | Alquife | Granada | Carboneras (7) | 149 km |

| 10 | Mercury | Almadén | Ciudad Real | Puertollano (6) | 91 km |

| 11 | Arsenic | Bellmunt del Priorat | Tarragona | Cercs (8) Escatrón (9) | 211 km 123 km |

| 12 | Copper, Silver | Riotinto | Huelva | Los Barrios (10) | 258 km |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez, R.; Bascompta, M.; García-Ordiales, E.; Ayala, J. Use of Fly Ash Layer as a Barrier to Prevent Contamination of Rainwater by Contact with Hg-Contaminated Debris. Environments 2025, 12, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12040107

Rodríguez R, Bascompta M, García-Ordiales E, Ayala J. Use of Fly Ash Layer as a Barrier to Prevent Contamination of Rainwater by Contact with Hg-Contaminated Debris. Environments. 2025; 12(4):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12040107

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez, Rafael, Marc Bascompta, Efrén García-Ordiales, and Julia Ayala. 2025. "Use of Fly Ash Layer as a Barrier to Prevent Contamination of Rainwater by Contact with Hg-Contaminated Debris" Environments 12, no. 4: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12040107

APA StyleRodríguez, R., Bascompta, M., García-Ordiales, E., & Ayala, J. (2025). Use of Fly Ash Layer as a Barrier to Prevent Contamination of Rainwater by Contact with Hg-Contaminated Debris. Environments, 12(4), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12040107