Cyber-Sexual Crime and Social Inequality: Exploring Socioeconomic and Technological Determinants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data on Sexual Cybercrime in Spain

2.2. Structure of the Spanish Educational System

2.3. Income Levels, Digital Behavior, and Household Technological Equipment

2.4. Classification of Cyber-Sex Crimes and Victim Age Criteria

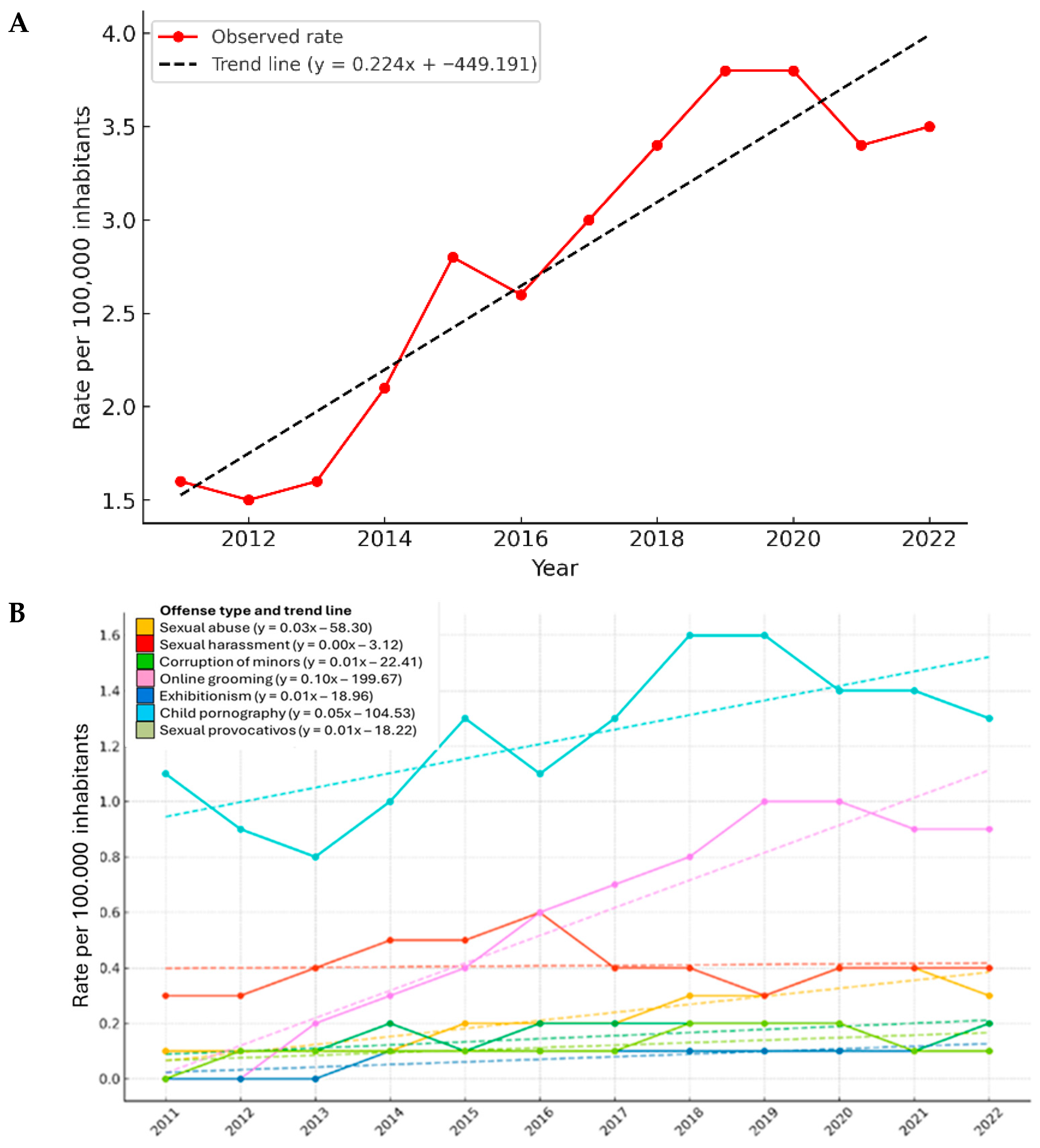

2.5. Temporal Trend Analysis

2.6. Cluster Analysis of Sexual Crime Rates Across Spanish Regions

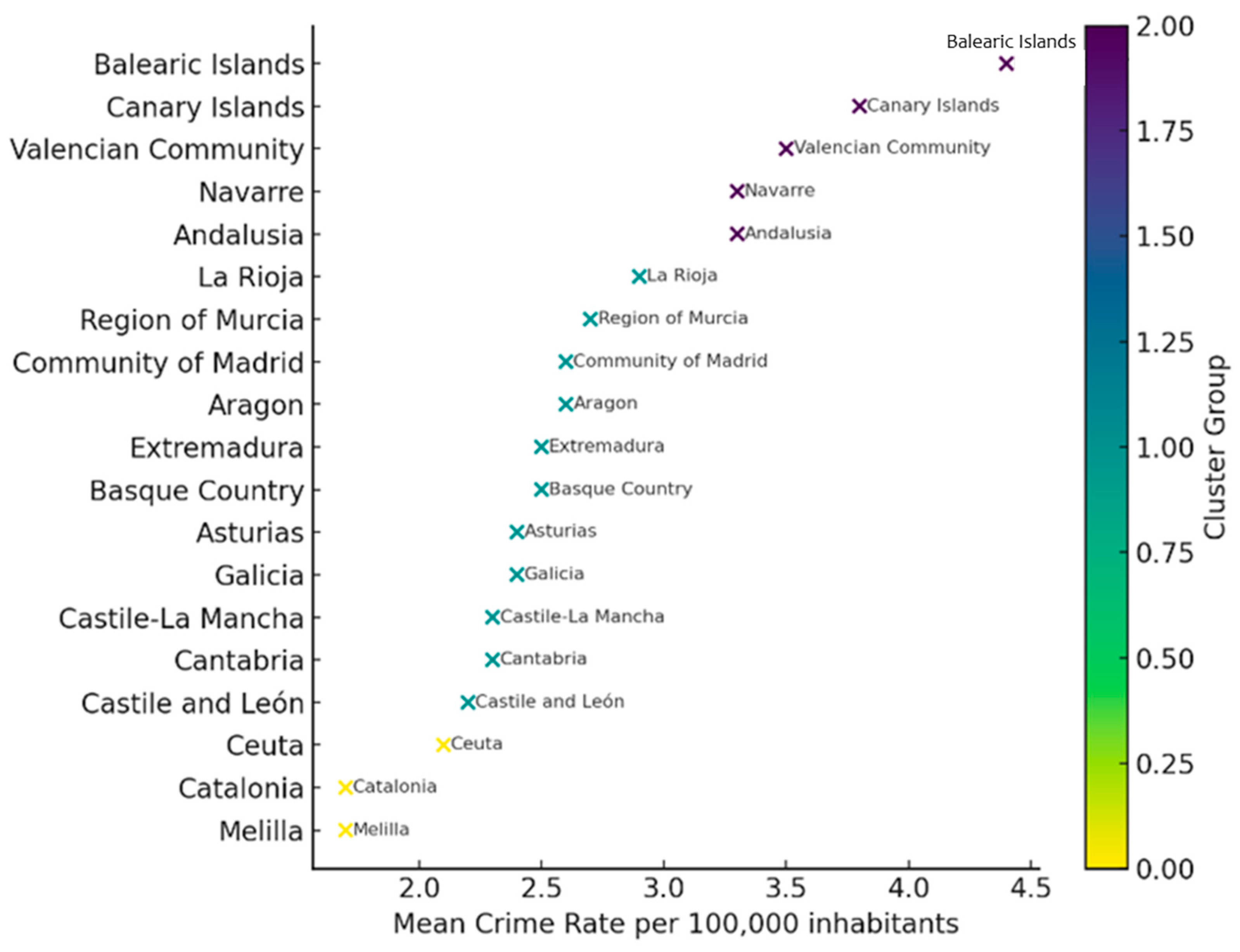

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. National Trends in Cyber-Sex Crimes (2011–2022)

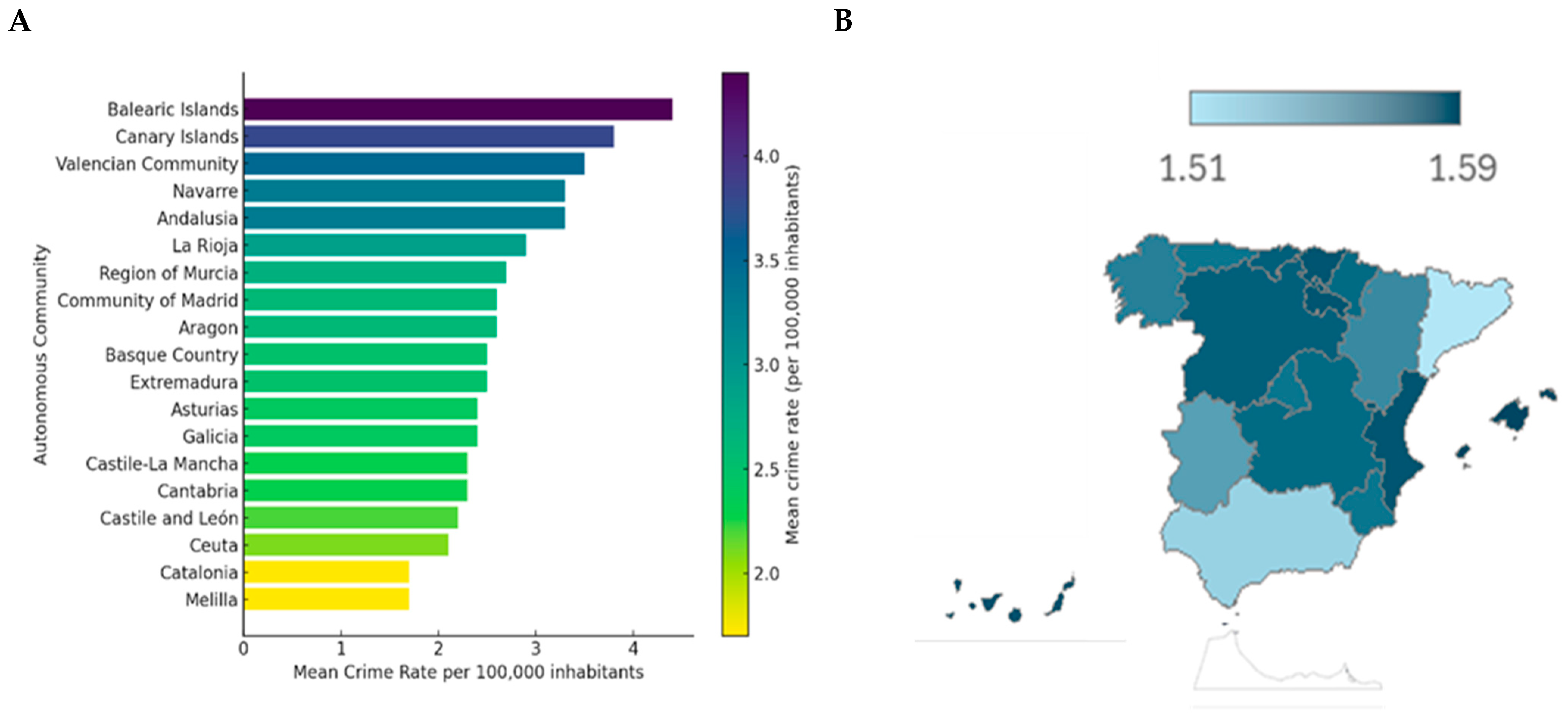

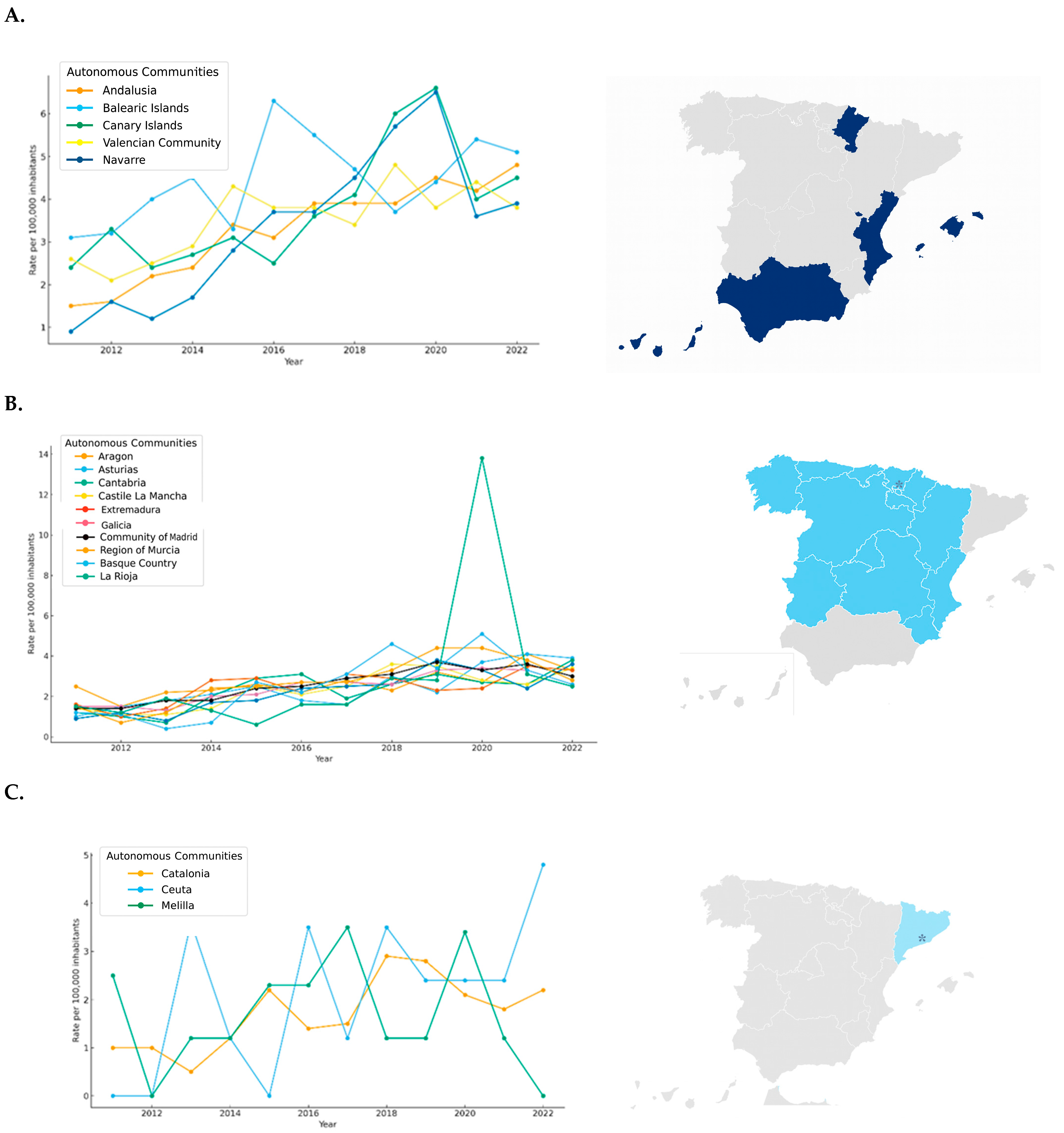

3.2. Analysis of Regional Variation and Temporal Progression of Cyber-Sex Crimes in Spain

3.3. Mean Cyber-Sex Crime Rates by Spanish Region (2011–2022)

3.4. Spatial Patterns and Cluster-Based Classification of Cyber-Sex Crimes in Spanish Regions

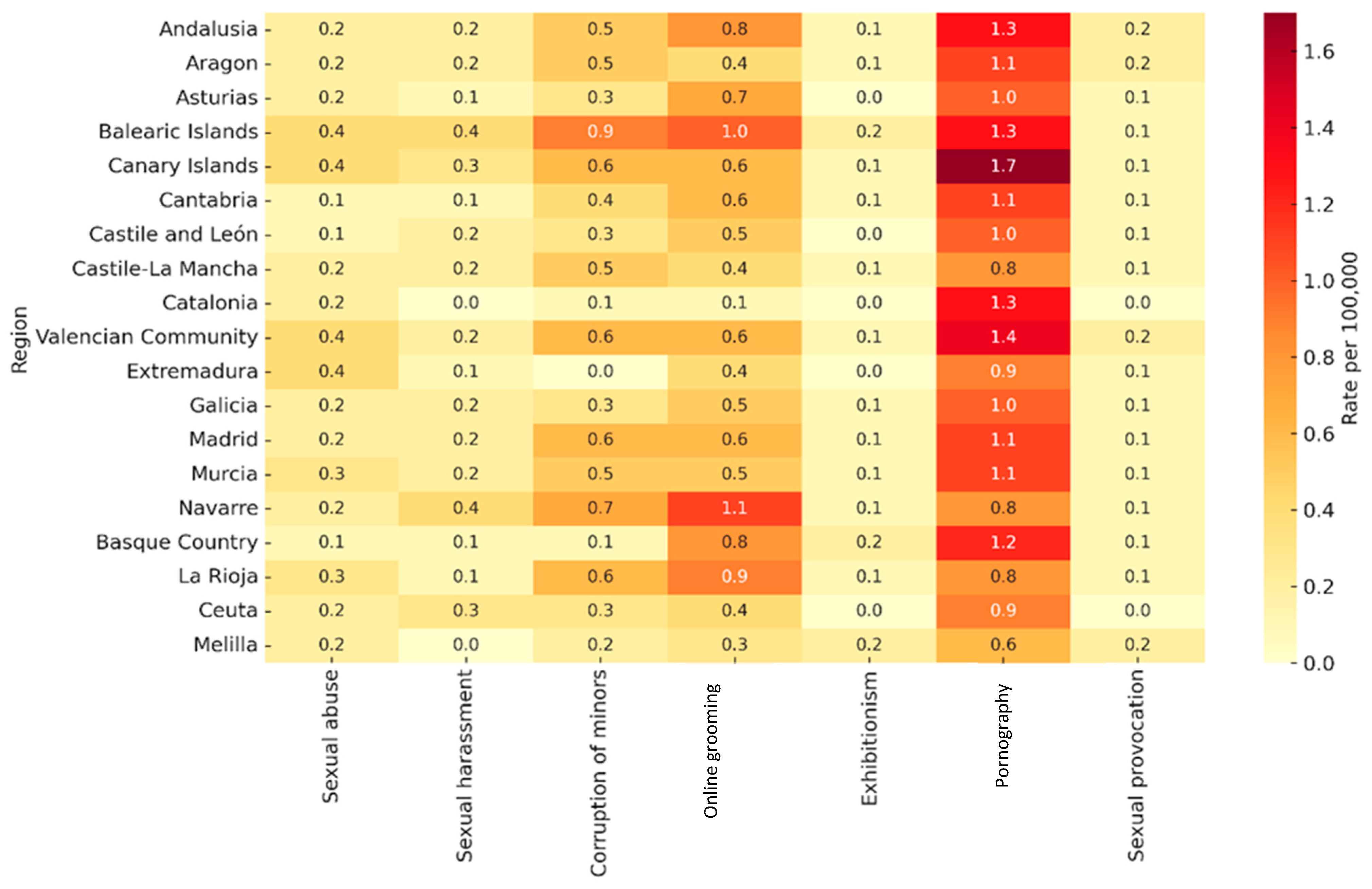

3.5. Comparative Analysis of Mean Cyber-Sex Crime Rates by Offense Type and Region

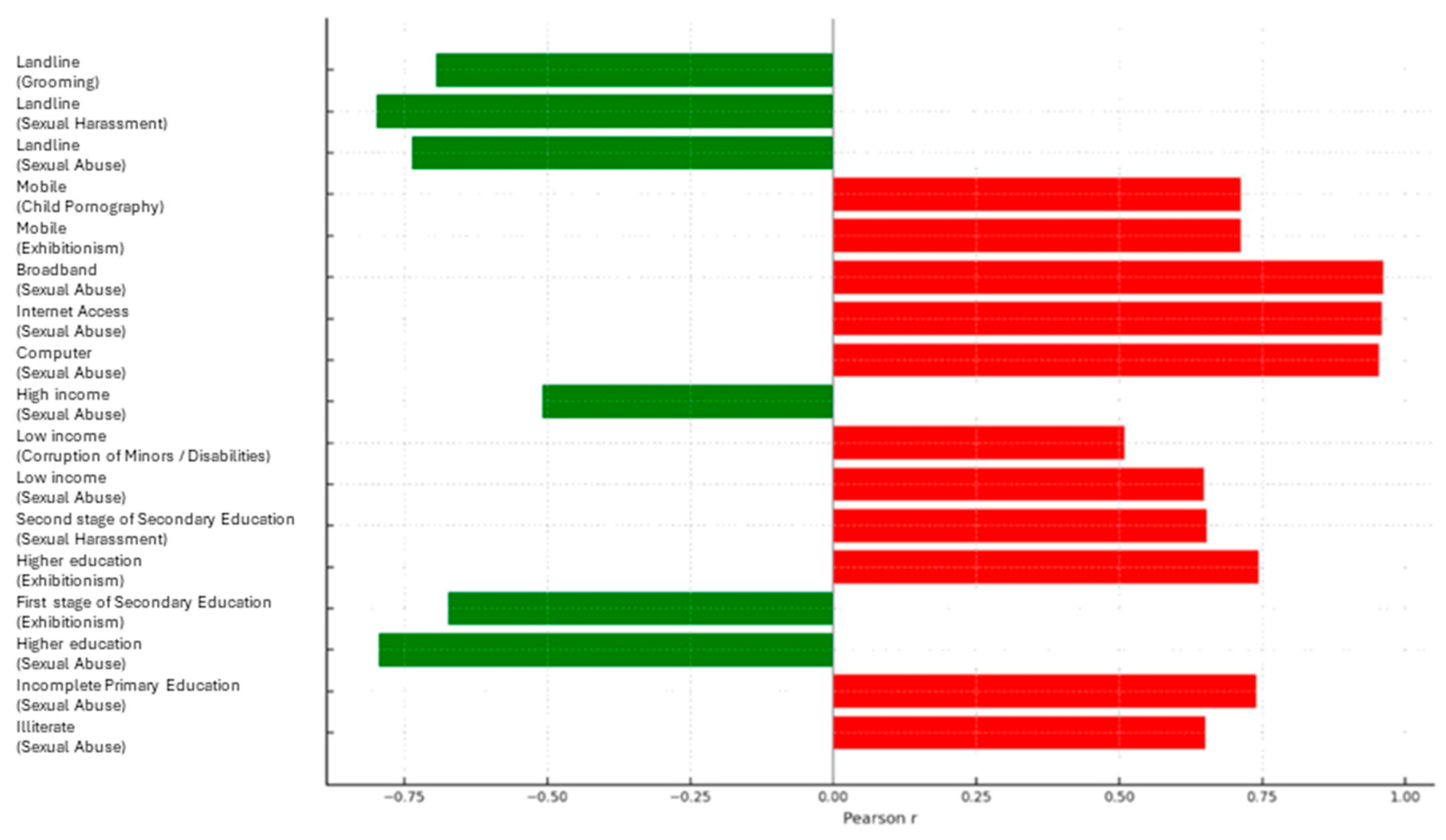

3.6. Analysis of Correlations Between Sociodemographic, Educational, Economic, and Technological Variables and the Incidence of Cyber-Sexual Crimes (2022)

4. Discussion

4.1. Structural and Regional Inequalities

4.2. Technological Factors and Emerging Digital Risks

4.3. Spatial Patterns, Prevention Strategies, and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abashidze, A. K., & Goncharenko, O. K. (2022). Protection of women from violence and domestic violence in the context of digitalization. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies, 254, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artículo 183 Del Código Penal | Codigo Penal Español. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.codigopenalespanol.com/codigo-penal-articulo-183/ (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Bock, H.-H. (2007). Clustering methods: A history of k-means algorithms. In Selected contributions in data analysis and classification (pp. 161–172). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullying and online experiences among children in England and wales: Year ending March 2023—Office for National Statistics. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/releases/bullyingandonlineexperiencesamongchildreninenglandandwalesyearendingmarch2023?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Calderón Gómez, D., Puente Bienvenido, H., & García Mingo, E. (2024). Generación expuesta: Jóvenes frente a la violencia sexual digital. Centro Reina Sofía de Fad Juventud. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14352/111138 (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Choi, K. S., & Lee, J. R. (2017). Theoretical analysis of cyber-interpersonal violence victimization and offending using cyber-routine activities theory. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data—Crime Statistics Portal. (n.d.). Available online: https://estadisticasdecriminalidad.ses.mir.es/publico/portalestadistico/en/ (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Espinosa Zárate, Z., Camilli Trujillo, C., & Plaza-de-la-Hoz, J. (2023). Digitalization in vulnerable populations: A systematic review in Latin America. Social Indicators Research, 170(3), 1183–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU guidelines for the International Classification of Crime for Statistical Purposes-ICCS 2017 edition. (n.d.). EU guidelines for the International Classifica-tion of Crime for Statistical Purposes-ICCS 2017 edition. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-manuals-and-guidelines/-/ks-gq-17-010 (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Evolución de datos de Viviendas (2006–2024) por tamaño del hogar, hábitat, tipo de equipamiento y periodo. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Datos.htm?tpx=70391#_tabs-tabla (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., & Colburn, D. (2022). Prevalence of online sexual offenses against children in the US. JAMA Network Open, 5(10), e2234471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, F. J. M., Del Pino, E., Cruz-Martínez, G., & Mari-Klose, M. (n.d.). Diagnosis of the situation for children in Spain before the implementation of the European Child Guarantee. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/eca/media/18851/file/Spanish%20Deep%20Dive%20Literature%20review%20EN.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Harduf, A. (2020). Rape goes cyber: Online violations of sexual autonomy. University of Baltimore Law Review, 50, 357. [Google Scholar]

- Hedidi, M., & Hedidi, M. (2023). Perspective CHAPTER: Sexual cybercrime—The transition from the virtual aggression to the physical aggression. In Forensic and legal medicine—State of the art, practical applications and new perspectives. IntechOpen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeks, R. (2021). From digital divide to digital justice in the global south: Conceptualising adverse digital incorporation. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, N., McGlynn, C., Flynn, A., Johnson, K., Powell, A., & Scott, A. J. (2020). Image-based sexual abuse: A study on the causes and consequences of non-consensual nude or sexual imagery. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, N., & Powell, A. (2018). Technology-facilitated sexual violence: A literature review of empirical research. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 19(2), 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Informe “Silenciadas” | Save the Children. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.savethechildren.es/actualidad/informe-silenciadas (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). (n.d.). Available online: https://www.ine.es/dynt3/inebase/es/index.htm?padre=8921&capsel=8933 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- ISO—ISO 3166—Country Codes. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.iso.org/iso-3166-country-codes.html#2012_iso3166-2 (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Kostin, G. A., Chernykh, A. B., Andronov, I. S., & Pryakhin, N. G. (2021, April 14). The phenomenon of tolerance and non-violence in the development of the individual in the digital transformation of society. 2021 Communication Strategies in Digital Society Seminar (ComSDS) (pp. 213–216), St. Petersburg, Russia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. (2023). Cyber crime: A review. International Journal of Advanced Scientific Innovation, 5. Available online: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/111527316/Cyber_crime_paper_to_publish-libre.pdf?1708091713=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DCYBER_CRIME_A_Review.pdf&Expires=1762538559&Signature=Fkb5erCuo5aJhuXjQIOnDU74dMgC3r5LRqlnr9m3X1NsvzOqDqV (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Lee, E., & Lee, H. E. (2024). The relationship between cyber violence and cyber sex crimes: Understanding the perception of cyber sex crimes as systemic issues. Children, 11(6), 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martellozzo, E. (2019). Online child sexual abuse. In Child abuse and neglect: Forensic issues in evidence, impact and management (pp. 63–77). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlynn, C., Johnson, K., Rackley, E., Henry, N., Gavey, N., Flynn, A., & Powell, A. (2021). ‘It’s torture for the soul’: The harms of image-based sexual abuse. Social and Legal Studies, 30(4), 541–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlynn, C., & Rackley, E. (2017). Image-based sexual abuse. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 37(3), 534–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monitoring EU crime policies using the International Classification of Crime for Statistical Purposes (ICCS). (2018). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-manuals-and-guidelines/-/ks-gq-18-005 (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Nota de Prensa: Atlas de Distribución de Renta de los Hogares. Año 2022. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/Prensa/ADRH2022.htm (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Población de 16 y más años por nivel de formación alcanzado, sexo y comunidad autónoma. Porcentajes respecto del total de cada comunidad (6369). (n.d.). Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=6369#_tabs-grafico (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Policing Sex Crimes—Dale Spencer & Rosemary Ricciardelli—Google Libros. (n.d.). Available online: https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=tCmgEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=cyber-sex+crimes+represent+a+particularly+alarming+phenomenon+due+to+their+prevalence,+complexity,+and+the+lasting+harm+they+cause+to+individuals+and+communities.&ots=LqB7BJ-u9x&sig=jJH-zCIw3Hw4pd5ee57KfnDm5HQ#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Portal Estadístico de Criminalidad. (n.d.). Available online: https://estadisticasdecriminalidad.ses.mir.es/publico/portalestadistico/datos.html?type=pcaxis&path=/Datos5/&file=pcaxis (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Powell, A. (2022). Technology-facilitated sexual violence: Reflections on the concept. In Rape: Challenging contemporary thinking—10 years on (pp. 143–158). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rackley, E., McGlynn, C., Johnson, K., Henry, N., Gavey, N., Flynn, A., & Powell, A. (2021). Seeking justice and redress for victim-survivors of image-based sexual abuse. Feminist Legal Studies, 29(3), 293–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragnedda, M., Ruiu, M. L., & Addeo, F. (2022). The self-reinforcing effect of digital and social exclusion: The inequality loop. Telematics and Informatics, 72, 101852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A., & Henry, N. (2025). Sextortion: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 26(1), 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydzewski, N. (2024). Number 2 Perspectives on the International Criminal Court and International Criminal Law and Procedure: A Symposium in Memory of Megan Fairlie. FIU Law Review, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secinaro, S. F., Oppioli, M., Demarchi, L., & Novotny, O. (2025). Bridging borders and boundaries: The role of new technologies in international entrepreneurship and intercultural dynamics. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 21(1), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segate, R. V. (2022). Navigating Lawyering in the Age of Neuroscience: Why Lawyers Can No Longer Do Without Emotions (Nor Could They Ever). Nordic Journal of Human Rights, 40(1), 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syakur, M. A., Khotimah, B. K., Rochman, E. M. S., & Satoto, B. D. (2018). Integration K-means clustering method and elbow method for identification of the best customer profile cluster. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 336(1), 012017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J. B. (2020). Mediated interaction in the digital age. Theory, Culture & Society, 37(1), 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umbach, R., Henry, N., & Beard, G. (2025, April 26–May 1). Prevalence and impacts of image-based sexual abuse victimization: A multinational study. 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, D. S. (2015). The internet as a conduit for criminal activity. International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 10(2), 235–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, H., Hamilton-Giachritsis, C., Beech, A., & Collings, G. (2013). A review of online grooming: Characteristics and concerns. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18(1), 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M. S., & Pavlou, P. A. (2020). Technology-enabled interactions in digital environments:a conceptual foundation for current and future research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(1), 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Regions | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | 1.5 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 4.5 | 4.2 | 4.8 |

| Aragon | 2.5 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 4.1 | 3.3 |

| Asturias | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 3.9 |

| Balearic Islands | 3.1 | 3.2 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 3.3 | 6.3 | 5.5 | 4.7 | 3.7 | 4.4 | 5.4 | 5.1 |

| Canary Islands | 2.4 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 3.6 | 4.1 | 6.0 | 6.6 | 4.0 | 4.5 |

| Cantabria | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 3.8 |

| Castile and Leon | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 3.6 |

| Castile-La Mancha | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 3.4 |

| Catalonia | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 2.2 |

| Valencian Community | 2.6 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 4.3 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 4.8 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 3.8 |

| Extremadura | 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 3.5 | 3.3 |

| Galicia | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 2.6 |

| Madrid | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 3.0 |

| Murcia | 1.5 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 2.8 |

| Navarre | 0.9 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 4.5 | 5.7 | 6.5 | 3.6 | 3.9 |

| Basque Country | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 4.6 | 3.4 | 5.1 | 3.3 | 2.6 |

| Rioja | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 13.8 | 3.1 | 2.5 |

| Ceuta | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.6 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 3.5 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 4.8 |

| Melilla | 2.5 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 3.4 | 1.2 | 0.0 |

| Types of Cyber-Sexual Crimes | Sexual Abuse | Sexual Harassment | Corruption of Minors/Disabilities | Grooming | Exhibitionism | Child Pornography | Sexual Provocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Educational level | |||||||

| Illiterate | 0.650 * | 0.111 | 0.233 | 0.185 | −0.310 | −0.193 | 0.497 |

| Incomplete Primary Education | 0.739 ** | 0.010 | 0.033 | 0.233 | −0.288 | −0.468 | 0.226 |

| Primary Education | 0.006 | 0.021 | 0.142 | −0.217 | −0.195 | 0.022 | −0.171 |

| First stage of Secondary Education | 0.600 | 0.079 | 0.243 | −0.074 | −0.673 * | −0.073 | 0.158 |

| Second stage of Secondary Education | 0.025 | 0.652 * | 0.407 | −0.011 | 0.016 | 0.296 | −0.005 |

| Secondary education, vocational training | −0.398 | 0.009 | 0.108 | 0.082 | 0.164 | 0.236 | 0.206 |

| Higher education | −0.795 ** | −0.351 | −0.481 | 0.020 | 0.743 ** | 0.093 | −0.256 |

| B. Mean annual net income per inhabitant | |||||||

| Low | 0.648 ** | −0.180 | 0.509 * | −0.083 | −0.246 | −0.017 | 0.338 |

| Lower middle | −0.031 | 0.004 | −0.148 | −0.294 | −0.125 | 0.304 | 0.011 |

| Upper middle | −0.366 | 0.361 | −0.365 | 0.017 | −0.173 | 0.180 | −0.066 |

| High | 0.508 ** | −0.014 | −0.278 | 0.261 | 0.462 | −0.271 | −0.358 |

| C. Internet and social media usage rate | |||||||

| Ever used the Internet | −0.154 | 0.130 | −0.084 | −0.217 | 0.062 | −0.176 | −0.063 |

| Use in the last 12 months | −0.149 | 0.109 | 0.008 | −0.262 | 0.031 | −0.073 | −0.145 |

| Use in the last 3 months | −0.21 | 0.136 | 0.005 | −0.114 | 0.111 | 0.045 | −0.166 |

| Weekly use | −0.176 | 0.078 | −0.019 | −0.153 | 0.000 | −0.033 | −0.085 |

| Daily use | 0.011 | 0.338 | −0.060 | −0.106 | 0.044 | −0.045 | 0.025 |

| Multiple daily uses | 0.065 | 0.214 | 0.016 | −0.181 | 0.086 | −0.259 | −0.081 |

| D. Type of Internet access equipment and computer connections | |||||||

| Computer | 0.954 *** | 0.931 *** | 0.189 | 0.956 *** | 0.773 ** | 0.748 ** | 0.501 |

| Internet Access | 0.959 *** | 0.936 *** | 0.255 | 0.972 *** | 0.800 *** | 0.762 ** | 0.530 |

| Broadband | 0.961 *** | 0.936 *** | 0.249 | 0.972 *** | 0.794 ** | 0.760 ** | 0.528 |

| Landline | −0.737 ** | −0.798 *** | −0.076 | −0.695 ** | −0.438 | −0.434 | −0.536 |

| Mobile | 0.960 *** | 0.926 *** | 0.225 | 0.939 *** | 0.712 ** | 0.712 ** | 0.575 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mármol, C.J.; Luna, A.; Legaz, I. Cyber-Sexual Crime and Social Inequality: Exploring Socioeconomic and Technological Determinants. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1547. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111547

Mármol CJ, Luna A, Legaz I. Cyber-Sexual Crime and Social Inequality: Exploring Socioeconomic and Technological Determinants. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1547. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111547

Chicago/Turabian StyleMármol, Carlos J., Aurelio Luna, and Isabel Legaz. 2025. "Cyber-Sexual Crime and Social Inequality: Exploring Socioeconomic and Technological Determinants" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1547. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111547

APA StyleMármol, C. J., Luna, A., & Legaz, I. (2025). Cyber-Sexual Crime and Social Inequality: Exploring Socioeconomic and Technological Determinants. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1547. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111547