Formation Mechanism of Legal Motivation Among College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model Involving Core Self-Evaluation and Social Support

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

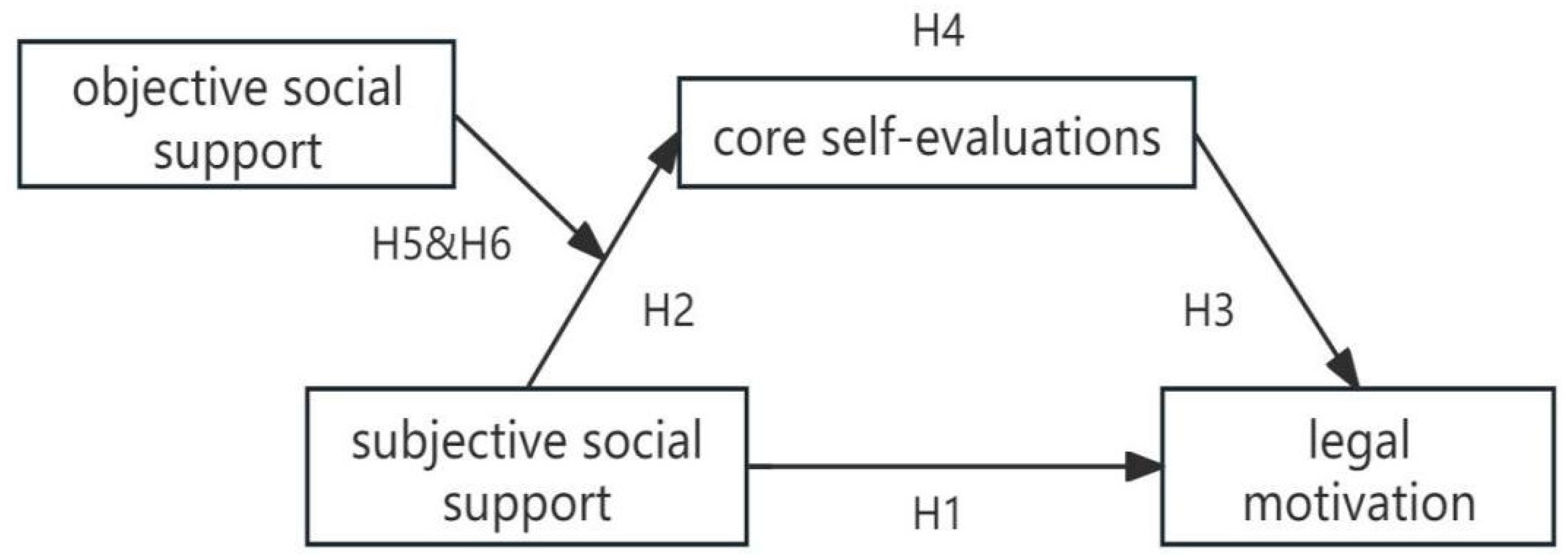

2.1. Relationship Between Subjective Social Support and Legal Motivation

2.2. Mediating Role of Core Self-Evaluation

2.3. Moderating Role of Objective Social Support

2.4. The Current Study

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of Common Method Variance

4.2. Tests for Demographic Variable Differences

4.3. Intercorrelations Among Key Variables

4.4. Mediation Analysis of Subjective Social Support → CSE → Legal Motivation

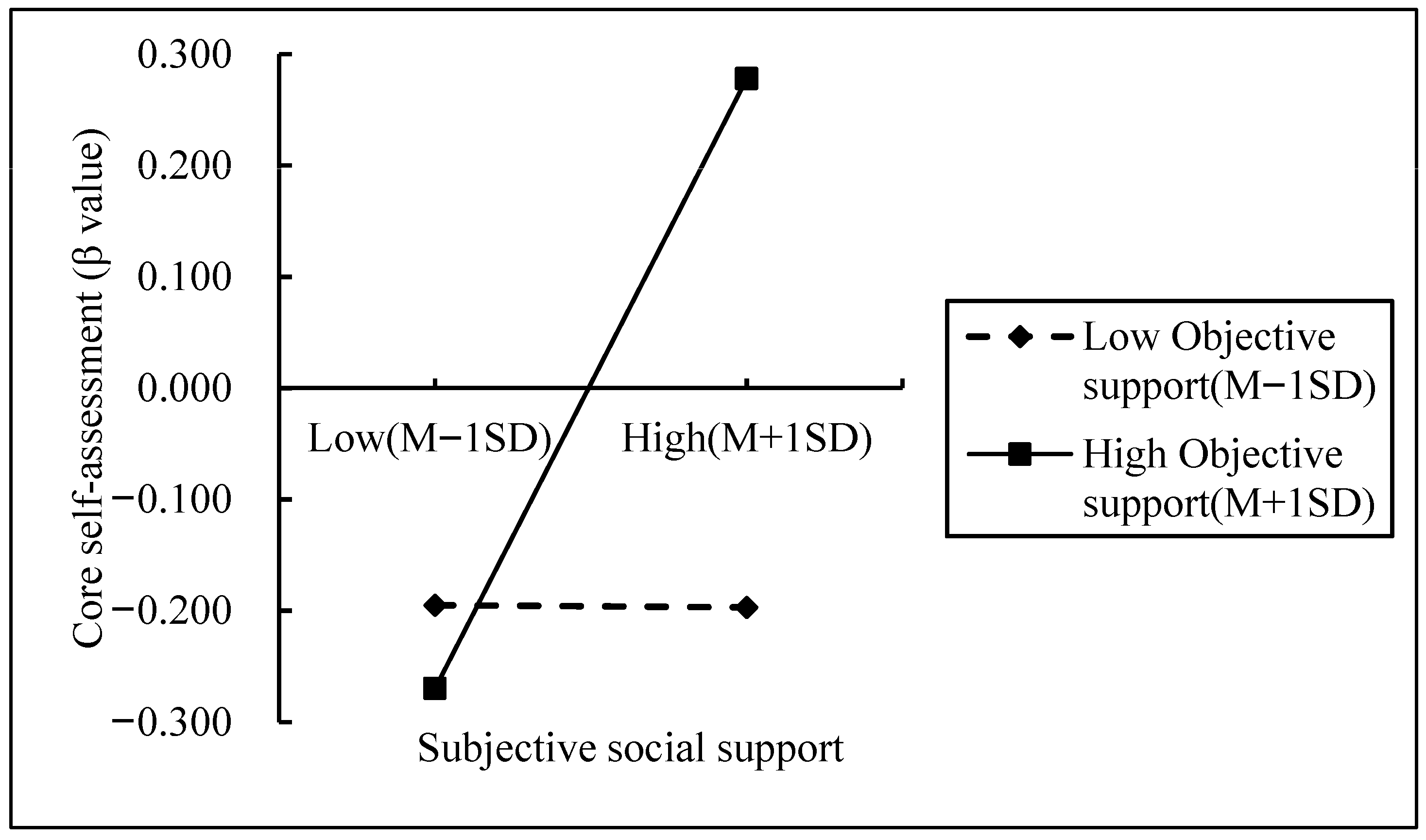

4.5. Moderated Mediation with Objective Social Support

5. Discussion

5.1. The Influence of Subjective Social Support on College Students’ Legal Motivation

5.2. The Mediating Function of Core Self-Assessment

5.3. The Moderating Role of Objective Social Support

5.4. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.5. Limitations and Strengths

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abhishek, R., & Balamurugan, J. (2024). Impact of social factors responsible for juvenile delinquency—A literature review. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 13(1), 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annie, C. M. (2011). Social learning theory and behavioral therapy: Considering human behaviors within the social and cultural context of individuals and families. Social Work in Public Health, 26(5), 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristotle. (1997). Politics (S. Wu, Trans.). The Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Brissette, I., Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (2002). The role of optimism in social network development, coping, and psychological adjustment during a life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, N. Y., Li, Z. S., & Zhu, X. D. (2024). Relationship between negative life events and emotional eating in college students: The mediating effect of self-control and moderating effect of self-esteem. Psychological Research, 17(06), 554–561. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C. H. D., Ferris, D. L., Johnson, R. E., Rosen, C. C., & Tan, J. A. (2012). Core self-evaluations: A review and evaluation of the literature. Journal of Management, 38(1), 81–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C., & Jia, C. X. (2024). Law awareness and abidance and radicalism prevention among Hong Kong youth. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 19, 2267–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coplan, R. J., Rose-Krasnor, L., Weeks, M., Kingsbury, A., Kingsbury, M., & Bullock, A. (2013). Alone is a crowd: Social motivations, social withdrawal, and socioemotional functioning in later childhood. Developmental Psychology, 49(5), 861–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dağ, İ., & Şen, G. (2018). The mediating role of perceived social support in the relationships between general causality orientations and locus of control with psychopathological symptoms. European Journal of Psychology, 14(3), 531–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahò, M. (2025). Emotional responses in clinical ethics consultation decision-making: An exploratory study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J., Zhang, X., & Zhao, Y. (2012). Reliability, validation and construct confirmatory of core self-evaluations scale. Psychological Research, 5(3), 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan, J., & Tyler, T. R. (2005). Legal socialization of children and adolescents. Social Justice Research, 18(3), 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangemi, A., Rizzotto, V., Riggio, F., Dahò, M., & Mancini, F. (2025). Guilt emotion and decision-making under uncertainty. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1518752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottfredson, M., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grey, I., Arora, T., Thomas, J., Saneh, A., Tohme, P., & Abi-Habib, R. (2020). The role of perceived social support on depression and sleep during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z. Y. (2023). Relationship between migrant children’s parenting style and self-control: The chain mediation role of family function and self-esteem. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 21(4), 503–509. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- He, J., Wang, Z., & Xu, S. (2025). How legal motivation buffers the effects of moral disengagement on school bullying among Chinese college students. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1583706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, T. (1996). Theory without ideas: Reply to Akers. Criminology, 34, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, L. P., & Graham, E. (2012). Resilience and well-being among children of migrant parents in South-East Asia. Child Development, 83(5), 1672–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—Self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—With job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T. A., Erez, A., & Bono, J. E. (2003). The core self-evaluations scale (CSES): Development of a measure. Personnel Psychology, 56(2), 303–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuan, H., Judijanto, L., & Lubis, A. F. (2024). The effect of legal awareness, access to justice, and social support on legal compliance behavior in MSMEs in Jakarta. West Science Social and Humanities Studies, 2(2), 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, N. (1987). Understanding the stress process: Linking social support with locus of control beliefs. Journal of Gerontology, 42(6), 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, N. (1997). Anticipated support, received support, and economic stress among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 52B(6), P284–P293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., & Nie, Y. (2010). Reflection and prospect on core self-evaluations. Advances in Psychological Science, 18(12), 1848–1857. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, N. (2001). Social capital: A theory of social structure and action. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J., & Wang, Q. (2018). Stressful life events and the development of integrity of rural-to-urban migrant children: The moderating role of social support and beliefs about adversity. Psychological Development and Education, 34(5), 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Fan, X., & Shen, J. (2007). Relationship between social support and problem behaviors of left-home-kids in junior middle school. Psychological Development and Education, 2007(3), 98–102. [Google Scholar]

- Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2002). Measuring perceived social support: Development of the child and adolescent social support scale (CASSS). Psychology in the Schools, 39(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S. E., & Cole, D. A. (2007). Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mladineo, M. (2019). Tom R. Tyler and Rick Trinkner (Eds.): Why children follow rules: Legal socialization and the development of legitimacy. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(5), 1022–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orehek, E., & Lakey, B. (2011). Relational regulation theory: A new approach to explain the link between perceived social support and mental health. Psychological Review, 118(3), 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrenas, R. S. (2001). Mothering from a distance: Emotions, gender, and intergenerational relations in Filipino transnational families. Feminist Studies, 27(2), 361–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S., Niu, G. F., Wang, X., Zhang, H. P., & Hu, X. E. (2021). Parental autonomy support and adolescents’ positive emotional adjustment: Mediating and moderating roles of basic need satisfaction. Psychological Development and Education, 37(2), 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15(3), 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisig, M. D., & Pratt, T. C. (2011). Low self-control and imprudent behavior revisited. Deviant Behavior, 32(7), 589–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisig, M. D., Wolfe, S. E., & Holtfreter, K. (2011). Legal cynicism, legitimacy, and criminal offending: The nonconfounding effect of low self-control. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38(12), 1265–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rullo, M., Lalot, F., & Heering, M. S. (2021). Moral identity, moral self-efficacy, and moral elevation: A sequential mediation model predicting moral intentions and behaviour. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 17(4), 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorr, M. T., Tietbohl-Santos, B., Oliveira, L. M., Terra, L., Telles, L. E. B., & Hauck, S. (2020). Association between different types of childhood trauma and parental bonding with antisocial traits in adulthood: A systematic review. Child Abuse & Neglect, 107, 104621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K. M., & Krieger, L. S. (2004). Does legal education have undermining effects on law students? Evaluating changes in motivation, values, and well-being. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 22(2), 261–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodeify, R., & Moghaddam Tabrizi, F. (2020). Nursing students’ perceptions of effective factors on mental health: A qualitative content analysis. International Journal of Community Based Nursing and Midwifery, 8(1), 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J., & Fan, H. (2013). A meta-analysis of the relationship between social support and subjective well-being. Advances in Psychological Science, 21(8), 1357–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekely, R. D., Opre, A., & Miu, A. C. (2015). Religiosity enhances emotion and deontological choice in moral dilemmas. Personality and Individual Differences, 79, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinkner, R., & Cohn, E. S. (2014). Putting the “social” back in legal socialization: Procedural justice, legitimacy, and cynicism in legal and nonlegal authorities. Law & Human Behavior, 38(6), 602–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinkner, R., Jackson, J., & Tyler, T. R. (2018). Bounded authority: Expanding “appropriate” police behavior beyond procedural justice. Law and Human Behavior, 42(3), 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T. R. (2003). Why people obey the law. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T. R. (2006). Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Annual Review of Psychology, 57(1), 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T. R. (2009). Legitimacy and criminal justice: The benefits of self-regulation. Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law, 7, 307–359. [Google Scholar]

- Tymoshenko, V. (2025). The role of the concept of “legal awareness” in the study of delinquent behaviour. Law Journal of the National Academy of Internal Affairs, 15(1), 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C., Tao, Y., & Jing, L. (2022). Core self-evaluation and subjective well-being: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 1036071. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, S. (1994). Theoretical foundation and research application of the social support rating scale. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 2, 98–100. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Y., Wang, J., & Wei, W. (2016). Perceived social support and anxiety in adolescents: The mediating role of emotion regulation. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 24(6), 1079–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., & Yan, W. (2022). The development characteristics, influencing factors and mechanisms of adolescents’ legal consciousness. Zhejiang University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yanovska, T. (2023). Awareness of guilt by juvenile criminals as a condition for successful resocialization. Psychology and Personality, 13(2), 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R., & Guo, M. (2018). The mediating effects of hope on the relationship between social support and social happiness in college students. Psychological Exploration, 38(2), 164–170. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y., & Dai, X. (2008). Development of social support scale for university students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 2008(5), 456–458. [Google Scholar]

- Zang, H. Y., Zheng, D. W., Lang, F., Liu, J., Zhang, Z. G., & Zhu, L. N. (2018). Mediation effects of self-efficacy and self-esteem in the relationship between perceived social support and mental health in college students with left-behind experience. Chinese Journal of School Health, 39(9), 1332–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Kong, M., & Li, Z. (2017). Emotion regulation difficulties and moral judgment in different domains: The mediation of emotional valence and arousal. Personality and Individual Differences, 109, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1 | |||||

| 2. Grade Level | −0.100 * | 1 | ||||

| 3. Legal motivation | −0.224 *** | 0.042 | 1 | |||

| 4. Core self-evaluations | −0.017 | 0.191 *** | 0.163 ** | 1 | ||

| 5. Subjective social supports | −0.105 * | −0.031 | 0.431 *** | 0.183 *** | 1 | |

| 6. Objective social supports | −0.141 ** | −0.043 | 0.399 *** | 0.140 ** | 0.689 *** | 1 |

| M ± SD | 92.21 ± 12.58 | 35.02 ± 6.76 | 19.46 ± 3.26 | 24.73 ± 3.69 |

| Variables | Legal Motivation | Core Self-Evaluations | Legal Motivation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| constant | 0.319 | 1.166 | 0.585 | 1.9582 | 0.387 | 1.413 |

| Subjective social supports | 0.404 | 8.488 *** | 0.185 | 3.590 *** | 0.426 | 9.037 *** |

| Core self-evaluations | 0.116 | 2.427 * | ||||

| Gender | 0.009 | 0.086 | −0.421 | −3.602 *** | −0.040 | −0.371 ** |

| Grade Level | −0.208 | −3.117 ** | 0.047 | 0.648 | −0.202 | −3.015 |

| R2 | 0.229 | 0.067 | 0.216 | |||

| F | 21.334 *** | 6.505 *** | 24.858 *** | |||

| Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | 0.426 | 0.047 | 0.333 | 0.519 |

| Direct effect | 0.404 | 0.048 | 0.311 | 0.498 |

| Indirect effect | 0.022 | 0.013 | 0.002 | 0.052 |

| Variables | Legal Motivation | Core Self-Evaluations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | |

| constant | 0.319 | 1.166 | 0.415 | 1.40 |

| Gender | 0.009 | 0.086 | −0.379 | −3.264 ** |

| Grade Level | −0.208 | −3.117 ** | 0.052 | 0.721 |

| Subjective social supports | 0.404 | 8.488 *** | 0.137 | 1.944 |

| Core self-evaluations | 0.116 | 2.427 * | ||

| Objective social supports | 0.027 | 1.397 | ||

| Subjective supports × Objective supports | 0.037 | 3.720 *** | ||

| R2 | 0.229 | 0.104 | ||

| F | 21.334 *** | 6.913 *** | ||

| Indicator | Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderated mediation effects | eff1 (M − 1SD) | 0.000 | 0.048 | −0.106 | 0.092 |

| eff2 (M) | 0.061 | 0.047 | −0.010 | 0.170 | |

| eff3 (M + 1SD) | 0.123 | 0.070 | 0.012 | 0.281 | |

| Comparison of the Effects | eff2-eff1 | 0.062 | 0.037 | 0.006 | 0.148 |

| eff3-eff2 | 0.124 | 0.075 | 0.013 | 0.296 | |

| eff3-eff2 | 0.062 | 0.037 | 0.006 | 0.148 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, S.; Wang, Z. Formation Mechanism of Legal Motivation Among College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model Involving Core Self-Evaluation and Social Support. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1548. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111548

Xu S, Wang Z. Formation Mechanism of Legal Motivation Among College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model Involving Core Self-Evaluation and Social Support. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1548. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111548

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Shuhui, and Zhiqiang Wang. 2025. "Formation Mechanism of Legal Motivation Among College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model Involving Core Self-Evaluation and Social Support" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1548. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111548

APA StyleXu, S., & Wang, Z. (2025). Formation Mechanism of Legal Motivation Among College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model Involving Core Self-Evaluation and Social Support. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1548. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111548