Factorial Structure and Psychometric Analysis of the Persian Version of Perceived Competence Scale for Diabetes (PCSD-P)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Objectives

2.2. Study Sample

2.3. Measurements

2.4. Procedure and Ethical Considerations

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Content and Face Validity

3.3. Construct Validity

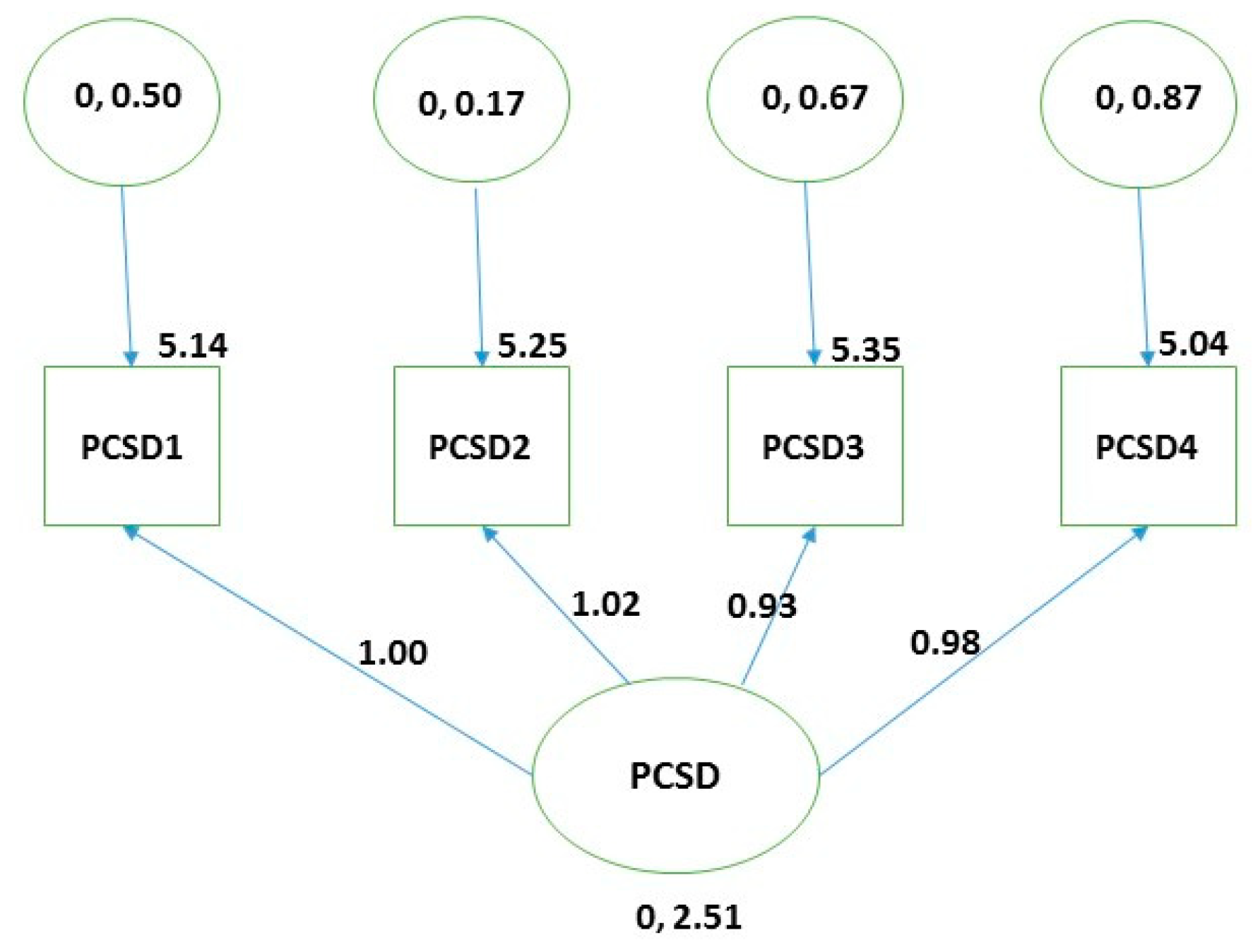

3.4. Reliability

4. Discussion

5. Limitation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mohn, J.; Graue, M.; Assmus, J.; Zoffmann, V.; Thordarson, H.B.; Peyrot, M.; Rokne, B. Self-reported diabetes self-management competence and support from healthcare providers in achieving autonomy are negatively associated with diabetes distress in adults with Type 1 diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2015, 32, 1513–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Report on Diabetes. Available online: http://www.who.int/diabetes/global-report/en/ (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Diabetes Programme. Available online: https://www.who.int/diabetes/goal/en/ (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Koponen, A.M.; Simonsen, N.; Laamanen, R.; Suominen, S. Health-care climate, perceived self-care competence, and glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes in primary care. Health Psychol. Open 2015, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, A.T.; Crittendon, D.R.; White, N.; Mills, G.D.; Diaz, V.; LaNoue, M.D. The effect of diabetes self-management education on HbA1c and quality of life in African-Americans: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 16, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- selfdeterminationtheory.org. Available online: http://selfdeterminationtheory.org/ (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1985; Available online: https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9780306420221 (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Nagai, Y.; Nomura, K.; Nagata, M.; Ohgi, S.; Iwasa, M. Children’s Perceived Competence Scale: Reference values in Japan. J. Child Health Care 2015, 19, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, A.M.; Brezausek, C.M.; Hendricks, P.S.; Agne, A.A.; Hankins, S.L.; Cherrington, A.L. Development of a Tool to Assess Resident Physicians’ Perceived Competence for Patient-centered Obesity Counseling. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2015, 3, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trew, K.; Scully, D.; Kremer, J.; Oghle, S. Sport, Leisure and Perceived Self-Competence among Male and Female Adolescents. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 1999, 5, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollerhed, A.C.; Apitzsch, E.; Råstam, L.; Ejlertsson, G. Factors associated with young children’s self-perceived physical competence and self-reported physical activity. Health Educ. Res. 2008, 23, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Empelen, R.V.; Jennekens-schinkel, A.; Rijen, P.C.V.; Helders, P.J.M.; Nieuwenhuisen, O.V. Health-related quality of life and self-perceived competence of children assessed before and up to two years after Epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia 2005, 46, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, J.M.; Goggins, K.M.; Nwosu, S.K.; Schildcrout, J.S.; Kripalani, S.; Wallston, K.A. Perceived Health Competence Predicts Health Behavior and Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 2071–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, P.A.; Palmer, R.T.; Miller, M.F.; Thayer, E.K.; Estroff, S.E.; Litzelman, D.K.; Biagioli, F.E.; Teal, C.R.; Lambros, A.; Hatt, W.J.; et al. Tools to Assess Behavioral and Social Science Competencies in Medical Education: A Systematic Review. Acad. Med. 2016, 91, 730–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instruments, Perceived Competence Scale (PCS). Available online: http://stelar.edc.org/instruments/perceived-competence-scale-pcs/ (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Williams, G.C.; Freedman, Z.R.; Deci, E.L. Supporting Autonomy to Motivate Patients with Diabetes for Glucose Control. Diabetes Care 1998, 21, 1644–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juul, L.; Maindal, H.T.; Zoffmann, V.; Frydenberg, M.; Sandbaek, A. Effectiveness of a Training Course for General Practice Nurses in Motivation Support in Type 2 Diabetes Care: A Cluster-Randomised Trial. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Koponen, A.; Simonsen, N.; Suominen, S. Health care climate and outcomes of care among patients with type 2 diabetes in Finland in 2011. J. Public Health 2014, 24, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, E.P.; Collinsworth, A.W.; Schmidt, K.L.; Brown, R.M.; Snead, C.A.; Barnes, S.A.; Fleming, N.S.; Walton, J.W. Improving diabetes care and outcomes with community health workers. Fam. Pract. 2016, 33, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, G.C.; Deci, E.L. Internalization of Biopsychososial Values by Medical Student: A Test of Self Determination Theory. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbek Minet, L.K.; Wagner, L.; Lønvig, E.M.; Hjelmborg, J.; Henriksen, J.E. The effect of motivational interviewing on glycaemic control and perceived competence of diabetes self-management in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus after attending a group education programme: A randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 2011, 54, 1620–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.C.; McGregor, H.A.; King, D.; Nelson, C.C.; Glasgow, R.E. Variation in perceived competence, glycemic control, and patient satisfaction: Relationship to autonomy support from physicians. Patient Educ. Couns. 2005, 57, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteghamati, A.; Larijani, B.; Aghajani, M.H.; Ghaemi, F.; Kermanchi, J.; Shahrami, A.; Saadat, M.; Esfahani, E.N.; Ganji, M.; Noshad, S.; et al. Diabetes in Iran: Prospective Analysis from First Nationwide Diabetes Report of National Program for Prevention and Control of Diabetes (NPPCD-2016). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islamic Republic of Iran. World Health Organization—Diabetes Country Profiles. 2016. Available online: https://www.who.int/diabetes/country-profiles/irn_en.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Nasli-Esfahani, E.; Farzadfar, F.; Kouhnavard, M.; Ghodssi-Ghassemabadi, R.; Khajavi, A.; Peimani, M.; Razmandeh, R.; Vala, M.; Shafiee, G.; Rambod, C.; et al. Iran Diabetes Research Roadmap (IDRR) Study: A Preliminary Study on Diabetes Research in the World and Iran. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2017, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Peimani, M.; Abrishami, Z.; Nasli Esfahani, E.; Bandarian, F.; Ghodsi, M.; Larijani, B. Iran Diabetes Research Roadmap (IDRR) Study: Analysis of Diabetes Comorbidity Studies in Iran: A Review Article. Iran J. Public Health 2017, 46, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Islam Saeed, K.M. Diabetes Mellitus among Adults in Herat, Afghanistan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cent. Asian J. Glob. Health 2017, 6, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajikistan. World Health Organization—Diabetes Country Profiles. 2016. Available online: https://www.who.int/diabetes/country-profiles/tjk_en.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Lawshe, C.H. A Quantitative Approach to Content Validity. Pers. Psychol. 2006, 28, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. The Content Validity Index: Are You Sure You Know What’s Being Reported? Critique and Recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2006, 29, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shultz, K.S.; Whitney, D.J.; Zickar, M.J. Measurement Theory in Action: Case Studies and Exercises, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 83–87. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=GjEkAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA87&lpg=PA87&dq=Formalizing+content+validity (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- Mirfeizi, M.; Asghari Jafarabadi, M.; Mehdizadeh Toorzani, Z.; Mohammadi, S.M.; Dehghan Azad, M.; Vizheh Mohammadi, A.; Teimori, Z. Feasibility, reliability and validity of the Iranian version of the Diabetes Quality of Life Brief Clinical Inventory (IDQOL-BCI). Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2012, 96, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, A.G.; Pearce, S. A Beginner’s Guide to Factor Analysis: Focusing on Exploratory Factor Analysis. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2013, 9, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohn, J.; Graue, M.; Assmus, J.; Zoffmann, V.; Thordarson, H.; Peyrot, M.; Rokne, B. The effect of guided self-determination on self-management in persons with type 1 diabetes mellitus and HbA1c ≥64 mmol/mol: A group-based randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemeth, C.P. Human Factors Methods for Design: Making Systems Human-Centered; CRC Press LLC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Process of Translation and Adaptation of Instruments. Available online: https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/ (accessed on 13 March 2019).

- Chehreay, A.; Haghdoust, A.A.; Freshteneghad, S.M.; Baiat, A. Statistical Analysis in Medical Science Researches Using SPSS Software, 1st ed.; Pezhvak e Elm e AriaL: Tehran, Iran, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, J.B.; Stage, F.K.; King, J.; Nora, A.; Barlow, E.A. Reporting Structural Equation Modeling and Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results: A Review. J. Educ. Res. 2006, 99, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frielink, N.; Schuengel, C.; Embregts, P.J.C.M. Autonomy support in people with mild-to-borderline intellectual disability: Testing the Health Care Climate Questionnaire-Intellectual Disability. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2018, 31, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Structural Equation Modeling Using AMOS an Introduction. Available online: https://stat.utexas.edu/images/SSC/Site/AMOS_Tutorial.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Schinka, J.A.; Velicer, W.F.; Weiner, I.B. Handbook of Psychology, Research Methods in Psychology, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; p. 92. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=MnOyiy5dtSsC&pg=PA92&lpg=PA92&dq=modification+indices (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Williams, G.C.; McGregor, H.A.; Freedman, Z.R.; Zeldman, A.; Deci, E.L. Testing a Self-Determination Theory Process Model for Promoting Glycemic Control through Diabetes Self-Management. Health Psychol. 2004, 23, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 63 | 35.6 |

| Female | 114 | 64.4 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 2 | 1.1 |

| Married | 151 | 85.3 | |

| Widowed | 22 | 12.4 | |

| Divorced | 2 | 1.1 | |

| Occupation | Employees | 10 | 5.6 |

| Retired | 26 | 14.7 | |

| Self-employed | 23 | 13 | |

| Housewife | 104 | 58 | |

| Unemployed | 3 | 1.7 | |

| Farmers/Stockbreeder | 11 | 6.2 | |

| Education | Illiterate | 63 | 35.6 |

| Primary education | 44 | 24 | |

| Secondary education | 23 | 13 | |

| High school level | 30 | 16.9 | |

| Post-graduate degree | 17 | 9.6 | |

| Place of residence | Urban | 145 | 81.9 |

| Rural | 32 | 18.1 | |

| Income level (RLs: The Iranian national currency) | <15 million | 106 | 59.9 |

| ≥15 million | 69 | 39 | |

| Without any income | 2 | 1.1 |

| Item | EFA Loadings |

|---|---|

| PCSD1 | 0.927 |

| PCSD2 | 0.953 |

| PCSD3 | 0.934 |

| PCSD4 | 0.927 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matin, H.; Nadrian, H.; Sarbakhsh, P.; Shaghaghi, A. Factorial Structure and Psychometric Analysis of the Persian Version of Perceived Competence Scale for Diabetes (PCSD-P). Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9050050

Matin H, Nadrian H, Sarbakhsh P, Shaghaghi A. Factorial Structure and Psychometric Analysis of the Persian Version of Perceived Competence Scale for Diabetes (PCSD-P). Behavioral Sciences. 2019; 9(5):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9050050

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatin, Habibeh, Haidar Nadrian, Parvin Sarbakhsh, and Abdolreza Shaghaghi. 2019. "Factorial Structure and Psychometric Analysis of the Persian Version of Perceived Competence Scale for Diabetes (PCSD-P)" Behavioral Sciences 9, no. 5: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9050050

APA StyleMatin, H., Nadrian, H., Sarbakhsh, P., & Shaghaghi, A. (2019). Factorial Structure and Psychometric Analysis of the Persian Version of Perceived Competence Scale for Diabetes (PCSD-P). Behavioral Sciences, 9(5), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9050050