Abstract

Drawing on a micro-phenomenological paradigm, we discuss Contact Improvisation (CI), where dancers explore potentials of intercorporeal weight sharing, kinesthesia, touch, and momentum. Our aim is to typologically discuss creativity related skills and the rich spectrum of creative resources CI dancers use. This spectrum begins with relatively idea-driven creation and ends with interactivity-centered, fully emergent creation: (1) Ideation internal to the mind, the focus of traditional creativity research, is either restricted to semi-independent dancing or remains schematic and thus open to dynamic specification under the partner’s influence. (2) Most frequently, CI creativity occurs in tightly coupled behavior and is radically emergent. This means that interpersonal synergies emerge without anybody’s prior design or planned coordination. The creative feat is interpersonally “distributed” over cascades of cross-scaffolding. Our micro-genetic data validate notions from dynamic systems theory such as interpersonal self-organization, although we criticize the theory for failing to explain where precisely this leaves skilled intentionality on the individuals’ part. Our answer is that dancers produce a stream of momentary micro-intentions that say “yes, and”, or “no, but” to short-lived micro-affordances, which allows both individuals to skillfully continue, elaborate, tweak, or redirect the collective movement dynamics. Both dancers can invite emergence as part of their playful exploration, while simultaneously bringing to bear global constraints, such as dance scores, and guide the collective dynamics with a set of specialized skills we shall term emergence management.

1. Introduction: Being Creative Together

Creativity and interaction research can glean new concepts from careful qualitative research on creative events. We observed Contact Improvisation (CI) dance couples, who agreed to participate in workshop-based think-alouds. The dancers explicated in minute detail what they perceived, thought, and planned in key creative moments. This first-person viewpoint, as well as the participatory experience of two of the authors (one of them with 25 years of CI experience), enables us to contrast different sources of embodied co-creation.

1.1. The Interactive Turn in Creativity and Improvisation Research

Creativity is commonly defined as behavior that combines functionality and novelty [1]. In traditional creativity theories, the subject of study are inventors, mathematicians, musicians, scientists, designers, and artists [2,3,4,5,6]. An implicit assumption dominates here that generativity is internal to the mind (i.e., individual creative achievements are in focus).

Against this backdrop, we must appreciate critical differences in performative domains where moments evanesce and ephemerality is inscribed in the modus operandi. For example, certain postmodern dance practices are not outcome-oriented, but oriented towards a continuous process and, often, towards the esthetics of experience. They also engage as much in problem finding as in problem solving, as the creativity literature would term it. The most fundamental difference, however, is that CI and many other types of improvised dance, when practiced in duets or groups, reach beyond “internal” (i.e., mentally and individually developed) creativity. The internal represents just one pole on a wider creativity spectrum. The analysis of performative creativity demands a transactional and thus also more “externalist” view, as philosophers would say. This approach has some important precursors we can build on.

First, concessions to interactivity are made by cognitive micro-process models, which conceive of creativity as an ongoing to-and-fro between generation of ideas, exploration, selection, and idea refinement. Notably, “geneplore” theory [7,8] proposes that generation stages cyclically alternate with exploration to further interpret implications and emergent structures of ideas one has. The generation stages operate through mechanisms such as retrieval of structures from memory, formation of associations between them, as well as combination, synthesis, and transformation of these structures; they also allow for analogy building, inter-domain mappings, as well as decomposition of existing structures into components. The exploration stages, in contrast, include searching for novel attributes, implications, functions, the evaluation from different perspectives, and thinking about conceptual limitations. At both stages, resource limits and practicality concerns may constrain the process. Hence, the generation of ideas, in effect, is cyclic and evolves by recursively harnessing different resources together. In this process, pre-inventive structures precede the final product, which can “be generated with a particular goal in mind or simply as a vehicle for open ended-discovery. They can be complex and conceptually focused, or simple and relatively ambiguous, depending on the situation or the requirements of the task” [8]. The mechanisms for generation and exploration include mental synthesis, mental transformation, and exemplar retrieval.

The interactive range of the creativity spectrum is also prefigured by studies of design and artistic creativity which emphasize continuous explorative activity over time, such as Schön’s [9] theory of design, and in particular interactions with objects and materials [10,11]. In some kinds of creative tasks, goals and emerging means co-evolve [12,13]. In cognitive science, similar ideas have been expressed by distributed and extended cognition theorists [14,15,16] who study how “thinking” happens in interaction with objects and environments. Agents engage in continuous solution probing [15,17,18], where serendipity plays a role, yet explorations also have a direction and involve “intelligent fumbling” [16,19].

Unfortunately, however, the most highly developed creativity theories to date bypass domains that involve multiple rapidly interacting agents such as in social dances, team sports, or collaborative music making. The interest in collective co-creation has largely remained limited to phenomena such as team brainstorming, while joint performance-based creativity is still ill-understood. The critical difference is that co-creation, under conditions of real-time joint performance, must happen rapidly and with extant resources, yet must also be coordinated. It subjects the participating individuals to moment-by-moment adaptive pressures that arise through the interaction itself. Joint performance is in this sense inherently improvisational, hence a “combined behavioural and cognitive activity that requires serial creativity under tight time constraint in order to meet performance objectives” ([20] p. 350). Furthermore, since jointly improvised performances are created in real time, the question of generativity commingles with issues of rapid motor implementation and how agents precisely coordinate their activities. Consequently, the participatory dynamic over time is central for explaining co-creation, a topic that we shall briefly introduce now and pursue in depth in several later parts of this paper.

1.2. Theories of Performative Co-Creation

Keith Sawyer, whose seminal work covers play, improvisation theater, small-group jazz, and everyday conversation [21,22], emphasizes that joint improvisation heightens all central characteristics of group creativity [23]: First, performative domains are inherently process oriented, and different from so-called product creativity as we might find in invention or design. Second, there is unpredictability, with a wide range of options at any point (although this may vary from context to context), as well as combinatorial complexity. Third, meaning is determined by interaction itself; a particular action may receive its meaning only through its response by other performers (often via retrospective interpretation). Therefore, group creativity ontologically “occurs on a collaborative, social plane rather than in performer’s heads” (ibid, p. 9). Fourth, there is complex (systemically constrained) communication where the communicative negotiation between agents occurs in parallel to the actual performance. Fifth, the performance creates higher-level structures that emerge from the interactions among individuals and exhibit global system behavior.

Our present contribution will explore another of Sawyer’s central performance related notions, the idea of distributed creativity [22], a derivative of the term “distribution cognition” proposed by Hutchins [24]. Distributed approaches situate cognitive functions beyond the mind: in interaction dynamics, social communication channels, structured work environments, organizational infrastructures, shared procedures, and—often—tools such as charts and instruments. Concerning creativity, the key insight of the distributed approach is that interaction supplies not only the medium for joint action, but becomes its generative source. We followed Sawyer’s agenda of developing an interactional semiotics of collaborative creativity, although we aimed to do it in a more micro-phenomenologically informed way that his social theorizing would suggest and we aimed to go well beyond his sign-based semiotics. As dance creativity is mediated by embodied processes and structures, our analysis was fundamentally indebted to post-cognitivist strands of embodied, embedded, extended, and enactive (“4E”) cognition [25], with at least three tributaries to the stream.

- Interactivity theory [17,18,26] and, closely related, participatory sense-making theory [27,28], and coregulation theory [29]: These accounts de-emphasize internal mechanisms and focus on what coupling based mechanisms do for explaining collective cognition and behavior. They focus on how continuous engagements provide progressively elaborated task solutions or lead to the negotiation of new interaction frames. This school of thinking has recently spawned important enactive approaches to creativity [30,31].

- Interactional self-organization and other complexity-theory concepts have been brought into play by sports and dance scientists, who study domains such as soccer, rugby or basketball that are co-improvised as well as creative [32,33,34,35]. These authors equally de-emphasize representations and mainly model collective dynamics mathematically.

- Integrative approaches combine first and third person inquiry. Interaction-dynamic, e.g., playful, and cognitive mechanisms were combined by Brian Magerko’s group [30,36,37,38]. Some of our own work [39,40,41] also falls into this category.

1.3. Togetherness Constrains and Enables Creativity

Across all domains, joint improvisational ideation needs a more complex treatment than solo performances. In creative duets or groups, we see information transactions, the building of joint resources, action-based synergy, and mutual reactivity and stimulation. Experts readily agree that being creative together is more challenging than it is in soloing, because one’s actions must also fit the concurrent actions of others. Thus, togetherness constrains: Many things that can tempt a soloist are ruled out, because they would mismatch the partner’s ongoing activities (or even abilities). The necessity for finely tuned coordination and—especially in dance—for looking after one’s partner’s physical safety imposes considerable constraints. Especially when all participants have equal decision power, interaction results in strict constraints on an individual’s creativity. After all, if agents develop their own separate creative intentions, these potentially clash unless agents manage to connect or negotiate them somehow.

On the other hand, togetherness equally confers benefits. It infuses the creative potential of individuals in multiple ways: (1) one can use immediate physical impulses between connecting bodies; (2) one can use the partner’s moves as thematic inspiration; (3) one can play, provoke, challenge, and surprise or playfully develop something together; (4) one can attain things that are physically impossible alone, i.e., “social synergies” [42] such a being lifted; (5) one can exploit re-afferences to self-produced stimuli of the partner; and (6) interactional cross-scaffolding can give rise to joint affordances or, as we show, let novel patterns emerge by and by. Thus, on the asset side, interaction itself can—if properly cultivated—become a resource and an explorative platform.

In both discussed respects, real-time coordination skills are irreducible, as studies of groups practicing jazz, classical music, flamenco, improvised theater, as well as CI [37,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52] clearly indicate. Smooth micro-coordination furnishes the baseline for togetherness, synergy, mutual inspiration and support, the factors upon which joint creativity builds. That is, a couple who interacts smoothly is also more successful regarding creativity. Quality coordination is, thus, not mere task execution. It becomes a principle of generation itself, a theme we explore at length in this paper.

2. Contact Improvisation

CI is a dance practiced in duets, but sometimes also in trios or small groups. It is pursued with an exploratory and experiential focus [53]. We have investigated this practice using a bundle of cognitive ethnographic tools.

2.1. A Short Introduction to CI from an Ethnographic Angle

CI dancing thrives on playful and explorative creativity and emphasizes inter-corporeal experimentation, curiosity, and self-surprise. It plays with the tension between one’s own impulses and collaborative opportunities inspired by the moment-to-moment dynamics and inter-body configurations. The dancers are mostly engaged in tactile-kinesthetic interaction, but may move in-and-out of contact. Weight-sharing situations predominate, and when dancers are in tactile contact, momentum is used to move in concert [54]. Observing the dance, bodies appear in a rather unpredictable succession of forms. The dancers may be upright, walking, jumping, lying and rolling; they may create counter-pull configurations, build cantilevers, allow a “rolling point” to move across the partner’s body or both bodies, “slough off” (i.e., slide down) another person, go into supported handstands, flips, or lifts, and a virtually endless number of possibilities. Physical contact may be restricted to one single point of contact, or extend to a larger area of the body. Shared weight, such as leaning into each other or counterbalancing each other, opens a doorway to the creation of momentum. This invites risk-taking, reflexes, controlled falling and rising, as well as disorientation, and moving through space together. The dynamics range from high, often acrobatic speed, to slow moving with more focused investment into details.

CI was founded in the 1970s to explore “reflex reactions of two bodies sharing weight through a moving point of physical contact” ([55] p. 42). Steve Paxton, who started the practice, describes this dance “as a spontaneous mutual investigation of the energy and inertia paths created when two people engage actively and dance freely, using their sensitivity to guide and safeguard them” ([56] p. 79). The open and transpersonal nature of the dance is what makes it interesting for its practitioners. CI dancers love to be “taken by surprise” [57]. Their joint creativity thrives on not knowing what will happen next. Dancers either look out for unfamiliar territories within familiar ones by modifying “known places” ([55] p. 42) or they move to “new places” altogether. Their dancing is motivated by “posing questions” to embodied attention [58]. Especially since CI is commonly practiced in the format of a silent jam, attentional skills are cultivated that result in a “heightened ability to sense through their skin and enhanced peripheral vision” ([55] p. 43). The inspiration to move can come from one’s own body, or from external stimuli (besides music). In exercising their creativity, dancers can choose to be completely free (apart from the physical forces that govern the movement) or follow some self-imposed task constraint or rule for some time [59].

Movement vocabulary in CI is not based on esthetic lines or shapes, but on interactively created challenges and sensation itself while playing with gravity and falling [55]. CI is known for its formal freedom and open vocabulary, especially when compared with traditional social dances. Besides safety, respect, and cooperation, CI has few constraints, being notable for its unique moments and fluidly emerging forms. All directions and body levels (upright, leaning, kneeling, lying, etc.), all kinds of interfaces (e.g., belly-to-foot, back-to-leg), and various kinds of dynamics and rhythms are admissible. Pausing or extremely subtle motion are equally possible.

It is true that novices may at first train “ready-mades” to learn deeper principles of CI; it is also true that on a CI jam one sees a certain amount of recognizable modules such as back flips, handstands, or lifts. However, experienced dancers point out that these familiar forms can arise as reflexes of their bodies, rather than as cognitive “ready-mades”, as we explain in detail below. As the essence of CI, experts emphasize unique qualities of encounter and connection as opposed to form. For these reasons, it is also rather misguided to analyze CI through the lens of serial combinations of familiar basic elements, a way of thinking cognitive scientists have applied, for example, to Lindy Hop [60] and ballet [61]. Applied to CI, this angle would miss the point, as its dance dynamics have no set junctures or elements of a pre-determined length that would suggest such an analysis. Finally, as Torrents et al. [59] pointed out, the (experiential as well as analytic) unit of action in CI is not the individual but the biomechanical and informational macro-system formed by the two dancers.

2.2. Research Findings on CI Creativity

Recent studies have piloted quantitative measures of CI creativity: A study by Carlota Torrents and colleagues [34] manually codes movements in six 5-min duets and four solos into CI-typical action classes. Compared to solos, the duets tended to generate higher dynamics and variability of action, as interaction produces a “divergent productions of responses” (p. 16). Moreover, creative fluency and flexibility vary with the pairings. Another study [59] analyzes dance processes as time-series in which dancers hop between locally stable behavioral attractors, without permanently settling anywhere. The authors applied dynamic systems metrics to compare: (a) the rate/breadth of exploratory behavior; (b) the coupling strength between partners; and (c) the way in which persistent (and from a skill perspective elementary) framing dynamics such as moments with both legs and both hands on the ground provide “seeds” for shorter-lived forms. Pertinent to our present topic, these findings link the breadth of exploration and creativity with skill- and task-based constraints. First, creative breadth shrinks under extreme instructional constraints such as having to stop when someone else in a group stops [62]. Instructions to keep the pelvises close together resulted in less creativity, whereas the (more CI-atypical) instruction to keep pelvises distant apparently enforced creative solution finding (and unconstrained dancing lay mid-way). Secondly, however, task constraints vary in power at different timescales. They impact creative breadth when measured at the 10-s timescale, but at the 1-s timescale constraints from the partner seemed more essential. Finally, creative breadth, somewhat predictably, grows with skill level [59]. For example, only novices find it difficult to dance with pelvises close and therefore produce stereotypical behavior [51].

2.3. What Kind of Creativity Does CI Highlight?

We now turn to some basic observations about the nature of CI creativity. Dancers report that creativity benefits from sensorimotor awareness of the here-and-now and “forgetting of the past”, from serendipity and happenstances. They do not always aim at novelty for its own sake; rather a rapport-based and kinesthetically aware attitude is deemed to lead to creativity as a welcome by-product. Taking up interpersonal stimulation and the act of joint exploration are fundamental. Consequently, an esthetics encapsulated in co-action itself is valued more than “Big C” creativity, as it is sometimes called.

Concerning the novelty aspirations of CI dancers, various loci may be distinguished: The most obvious locus lies in new forms, configurations, and dynamics, including hybrids of known material. The novelty here can consist in athletic virtuosity or ease of execution, or the relation to the own or other body and/or surrounding spatiality. Similarly, dynamic qualities of the dance can be exceptional, and some dancers like to invest much creativity, for example, into the “musicality” of the dance. The fact that dancing has a sequential aspect to it opens the possibility of building meaningful temporal gestalts, rhythms, and combinations. Aspects of such serial creativity can go as far as creating “narrative” developments or motif building, often at the timescale of minutes. In the smaller interstices of the moment, we observe two phenomena: On the one hand, virtually all dancers seek novelty at the interpersonal level concerning communication, as well as curiosity about partner reactions and the affective dynamics between the partners. On the other hand, dancers can fill “familiar places” with new qualities, including micro-dynamic qualities, communicative qualities, a new relationship to context, or a hitherto unachieved naturalness of initiation from ongoing dynamics. Even a handstand can be creative with respect to how it figures in context and how it arose dynamically. One dancer spoke of “a new pathway to a situation that itself was …more conventional”. Thus, new contexts, accentuations, specific new tactile or proprioceptive qualities, as well as dynamic variations may endow what otherwise would appear as a “ready-made” with creative qualities. Accordingly, our experts agree that creativity can relate to subtle, even unobservable qualities in the movement or nuances of perception. Here, the creative “how” is more in focus than the “what”. Both the communication level and the qualities of movement can be captured by what we would term micro-creativity. Occasionally, CI practice is also open to transformational creativity [63] which shifts the implicit boundaries and conventions of a domain (or creates genre hybrids such as Contact Tango).

From a comparative angle, and informed by questions that speak to the general creativity literature, seven defining characteristics of CI creativity meet the eye:

(1) As mentioned, CI is process-oriented and improvisational. A constant stream of action decisions is made without delay, using present resources, and in response to current constraints and adaptive pressures. Any creative process must build on what is readily at hand, often rapidly. Although creative processes need not be exceptional, great priority is placed on the action being highly situation-aware, and transparently communicated.

(2) CI creativity is biomechanically constrained and spatially located. Whatever comes next must fit the current situation. The dancers cannot skip between constellations in space as a keyboard player might. CI practitioners always need to pick up from where they are and their actions should offer continuation options for the moment that follows. Although this is not a strict constraint, constancy and continuous movement flow are considered important. Lesser constraints operate on the level of sequentiality. Although dancers continuously add to an emergent structure (Sawyer speaks of “emergents”, [23]), the movements are causally cumulative only to a limited degree, i.e., only when acrobatic moves demand closure for the sake of safety. (This contrasts with improvisation theater where additions have to make sense retrospectively and with respect to prospective narrative closure [21], and with soft martial arts where a defence is built up over several stages [64].)

(3) Most CI creativity happens intercorporeally, through joint kinesthesia. Joint exploration of space, mutual sensory explorations of the partner’s body, functional interpenetration with the partner are vital, where a macro-system of two bodies arises. Sharing surface contact provides the ideal medium for ceaseless negotiation. At the same time one adapts to the partner, the partner is adapting to oneself. Analytically, we may speak of mutual incorporation and kinesthetic interconnectivity [65,66,67], and a bidirectional coupling between sensorimotor systems that allows minimally delayed reactions as well as co-modulations of ongoing contributions of the partner. At many moments, shared weight systems or force vectors that run through both bodies are maintained through touch. The moment when weight is carried through another moving body is full of potential for encounter, surprise, and emergence.

(4) Even when dancers are not aiming for creativity, they are ready to react and to adapt to momentum or gravity. After all, the partner might always come up with an idea, the configuration may flip into something different, or new short-range goals emerge. In fact, dealing with surprises, novelty, and emergent risks is the dancers’ raison d’etre. Creativity acts often arise as response to biomechanical adaptation pressures. What counts as adaptive reaction can mean different things in CI: In many instances efficiency and biomechanical economy are given priority, yet in others dancers do not follow the natural path of energy flow, but seek creativity by leaving their comfort zone and by courting risk on purpose (albeit without compromising the quality or continuity of rapport).

(5) In addition to biomechanically necessary adaptations, interior experiential qualities in the ephemeral present are cherished. CI has a domain-specific esthetics that goes beyond just managing one’s way out of tricky situations or the search for physical efficiency alone. We need to think of CI as exemplifying a sort of “survival-creativity-plus” (to adapt Torrance’s [68] idea of survival creativity). CI embodies what creativity researcher Welling [6] has noted more generally: the implicit selection criteria that determine what an acceptable solution is comes from a mix of survival value and esthetic criteria. Although the dancers need to mind safety before getting creative, CI cultivates embodied curiosity for its own sake and, furthermore, provides an arena to explore cultural semiotics of touch and kinesthesia. In its experiential orientation and exploration, CI is similar to other art forms, and challenges merely adaptability-focused theories of creativity [69].

(6) CI creativity is explorative and playful. The participants regard the joy of discovery and curiosity as purposes in themselves, an embodied esthetics with immediate affective payoffs [38,70]. Time and time again, we have heard emphasized the gratification of sharing physical exploration and surprise. As in any playful activity, problems need to be found or even invited rather than being set. In this capacity, CI combines problem solving (albeit not always of well-defined problems) with problem finding [71]. Another factor related to playfulness is that the dance system is kept very malleable and responsive. The degree of constraints dancers wishes to set at a given moment is largely up to them (as opposed to social dances such as salsa or tango with a strict “grammar”).

(7) CI creativity is not only a joint process, but also a constantly interactive one that links the dancers in a double loop of simultaneous feedforward and feedback. This type of interaction has been called coregulation [29], a real-time process of meaning making, or—as we might say—of continuous decision-making-in-action [64]. The dancers source themes, inspirations, challenges, as well as solutions from the transaction of information and physical momentum. Since information flows and actions are mostly simultaneous (and in this respect quite unlike conversational turn-taking) physical impulses can mix into something genuinely new. Hereby, the creative process may become interactive in a deeper ontological sense. Collective dynamics and the participatory process of engagement over time [72] drive generativity (see Section 5.7 and Section 5.8).

3. Methodology

After this general outline, we are ready to introduce the particular methodology used in this study. As a first step in our data collection, we conducted dialogical interviews with five individual CI dancers. The participating dancers have been practicing CI for 15 years or longer, and teach CI internationally. One of our informants, Nita Little, co-developed CI together with CI founder Steve Paxton and others in the early 1970s and has been teaching it since. The interviews gave us an idea of our informants’ dance personalities and histories; as well as allowing us to probe resources, personal styles, and creativity interests. In a second step, we aimed at a genuine interactional semiotics for joint improvisation [23], using methods that are incident-based and can provide a high-zoom factor on the process of co-creation.

Specifically, we organized 21 think-alouds in the dance studio with pairs of dancers in sessions that lasted between 2.5 and 4.5 hours. Our aim was to closely track unique dance incidents of approximately 2–7 seconds, which we had selected together with the dancers. To elicit micro-genetic descriptions, we then encouraged the dancers to inspect the event from different angles. Recursive probe question were asked and our informants were required to stay close to the sensorimotor level while abstaining from generalizations. A detailed description of short perception–action cascades emerged from this dialogue, complemented by a final synopsis, comparisons to similar events, and how the event related to their dance experience in general (hence, we wrapped up by allowing a certain amount of more general reflections). On a few occasions, we elicited responses during the dance, but predominantly we engaged in a dialogue immediately after dancing while the dancers inspected video feedback on a tablet computer. In several of the think-alouds, we also used quasi-experimentation. For example, a dancer was asked to strategically perturb the interaction so we could observe the partner’s adaptations. To better understand adaptive constraints, we also asked dancers to progressively degenerate a specific movement pattern or subtly alter the context until another action strategy became more attractive.

Throughout, we employed micro-genetic interviewing techniques that help informants access tacit or embodied knowledge and elevate it above the threshold of consciousness. A tried-and-true micro-phenomenological method, the Explication interview [73,74,75], was customized for topics in sensorimotor interactions. This format allows informants to jointly explore their experience in a dialogue. The researcher’s role is to help sustain attention on a precisely circumscribed micro-experience, often a decision or pre-decision moment. Explication interview techniques are known to enable informants to verbalize subtle details of their embodied coping skills, and allow for tacit knowledge to become accessible in the first place. The sustained attention allows “blowing up” micro-moments of around one second or less for fine-grained inspection.

In the subsequent data analysis, the (recursive and cyclic) questions were reworked into a timeline model that shows how the dancers mutually cue and enable one another. Thus, detailed scores of dance snippets were reconstructed, as to who felt what when and where, which affordances were recognized, what information they consisted of, when actions set in, how actions complemented each others, or when transitions set in.

Up to now, 20 think-alouds were transcribed and analyzed, which we screened for instances of conspicuous creativity (defined as psychological creativity after Margaret Boden [63], not historical creativity). We then matched up the most notable examples with theories of creativity and from this created a functional taxonomy of creativity types. Short empirical examples to illustrate this taxonomy, as well as a more detailed process vignette, are reported in Section 5. (For space reasons, we had to condense the extended case descriptions; we instead supply selected quotations, which—although incident-based—were selected to be representative of our data pool.) Moreover, our think-alouds and interviews led to a useful survey of creativity skills in CI, as we report next.

4. Results I: Skills that Make Dancers Creative

Our survey of empirical findings begins with skills that our dancers deem central. In the field of CI, embodied and creative abilities cannot be neatly disentangled, since the latter presuppose the former. By degree, however, we may distinguish: (a) skills that enable joint creativity and provide conditions of possibility, as it were (Section 4.1, Section 4.2, Section 4.3 and Section 4.4); and (b) creativity techniques in the narrower sense (Section 4.5).

4.1. Enabling Sensorimotor Skills

Our team has learned from various previous studies on martial artists, dancers, and bodyworkers that improvisation never happens out of the blue. It presupposes highly prepared background structures and a readiness of mind and body. We therefore began by asking our CI informants specifically which habits kick in when the dance begins and how they bestow a “joint-improvisation-friendly” structure on their bodies. Precise technical habits are of paramount importance for the dancers: They are able to align one’s weight along the skeletal structure. They habitualize the ability to shift weight in any direction in space, independently of what the base support is (which can be any combination of extremities and/or torso), which enables reacting to subtle external impulses in any position. They remain, as a default, permeable and cultivate softness of muscle tone. Other habits are interpersonal: These include respecting constraints on dyadic geometries that allow for stable weight sharing, providing safe support in some positions, and many others. The primary purpose of good habits is to enable efficient movement, readiness, and rapport. Only if the right degrees of freedom are perfectly controlled, the body is optimally ready for situated action. However, good habits are no less creativity enabling. With an organized system of habits in place rapid motor cognition is facilitated: (1) the mind is freed for creativity; and (2) the number of effortlessly accessible affordances for action grows, notably when agents stay poised in a state of constant readiness so their body remains available for moving into any direction.

Technical training of specific action skills is equally vital to good improvisation. Dancers learn to modulate and vary muscle tones across body parts and to use different qualities of touch to adapt in variable ways. Moreover, acrobatic skills such as rolling, falling, going upside down, falling backwards prove helpful in many situations. They learn to create “architectures” between bodies such as cantilevers and support the body weight of the partner through structural intelligence and the least amount of effort. Dancers learn to retain their agency even in disoriented states such as spinning, hanging or other upside down positions.

Furthermore, a rich set of perceptual skills underpins improvisation. Dancers acquire kinesthetic interconnectivity, i.e., to let the senses reach forth into the partner’s body, even into distal locations, through a point of contact and send impulses there. Quite generally, our informants report that it takes particular kinds of attention to know what is going on and exploit sudden opportunities. Specific skills for “listening”—as dancers metaphorically call it—allow them to respond in the very moment. Their gaze apperceives the whole configuration. They hone their attention to tactility (friction and warmth), pressure, and their internal proprioceptive or kinesthetic states, and, when touching someone, can selectively focus on the skeleton, skin, muscles/fascia or other internal structures. Dancers learn to track their partner’s scope of attention and even recognize intentions based on incipient actions and gaze. To refine their reflexes, dancers train to become precisely aware of balance, momentum, weight distribution, weight sharing, and their partner’s as well as their own relationship to the ground. Experienced dancers are aware of the quality of touch, temperature, heartbeat, gaze, the dynamics of posture and limb placement, muscle tone, its distribution across the body, and tissue compression; they read the interpersonal body geometry, speed differentials, distances, angles, trajectories, and force vector configurations (levers, fulcrums, etc.).

4.2. Skill Refinement at High Proficiency Levels

The CI teacher Nita Little ([76] p. 251) suggests that dancers should cultivate a specific kind of embodied attention that increases their proprioceptive and kinesthetic potentials:

To teach embodiment that is both located and expansive in spacetime, I support the dancers’ attentional articulation. I want to move them into the experience of the very small in oscillation with the very large (or scale changing) and places in oscillation with actions that feel spatial. This work is an extension of the attention training I learned when Steve Paxton taught the ‘small dance’ of balance as a means to study embodied conscious states. It is what he calls an ‘interior technique’ [...]. As with the small dance, interior techniques teach dancers to experience themselves as organizing spatially along trajectories and other geometries, perceiving changes and their potentials, while making multifaceted, finely tuned decisions along the way. This practice teaches a deep relaxation in counterpoint to a quickening and the ability to be touched while touching, to be changed while changing and to awaken attention to the polyrhythms of bodies, including to a body ‘standing’ in the small dance.

Similarly, our informants mention the importance of “listening” and expanding their attention, especially when entering into risky or unpredictable dynamics:

The less predictable we are, the more we have to listen to each other. […] if you have the intention of honing your attention to smaller and smaller... quantity of details. […] the thin-slicing will take you into improvisation.

With “thin-slicing”, the dancer here refers to a mode of perceptual awareness and control, which continuously stays with the ongoing dynamics. This supports motor control. It allows making a continuous stream of micro-decisions without overshooting or lagging behind, i.e., a mode of dynamic immediacy [77]. Dancers can now confirm or disconfirm extant dynamics with “homeopathic” responses. This means they scale their movements very precisely and just as much as they need, which a dancer describes as follows:

It’s definitely not plan making and it’s also not “when this happens, that happens” so it’s not a cause-effect learned thing. In some way, it’s even faster than thinking, in the sense of thinking as a conscious score or creating a conscious intention. It’s much faster than that. Sometimes it’s just mirroring her like responding kind of like homeopathically—like the same thing she gives me, I give back and see what comes then. Sometimes it’s kind of like feeling like completing it or following it, but sometimes it gives me an idea that is suddenly there and I just do it.

In terms of reactivity and micro-coordination, this indicates that CI dancers, instead of planning and anticipating, become capable of intelligent reflexes [78]. Some of our informants associate this interaction modality with a specific CI “idiom” of following the kinesthetic flow, as opposed to an extensive use of muscle force to shape and uphold acrobatic positions. The previous informant’s partner opines as follows on what makes ultra-rapid action and reaction possible in the first place:

She [her partner] said, it’s faster than call and response. So that means to me that what’s happening, has to be happening on the level of what I call, peripheral intelligence. Which is, it’s not getting up to the skull. It’s happening on the level of our interweaving as physical-mental forms. But there is creativity there, so there is some level at which choices are being made.

In this quote, the second dancer apparently attributes exceptional reaction speed to how features of the peripheral fascia and muscles are organized so that they react intelligently (for related ideas see Section 6.1).

Another special ability of experienced CI dancers is to maintain field awareness at each moment in the dance whereby the current situation gestures at the range of possible short-range futures. As part of pre-reflexive embodied orientations to contexts [79,80] dancers orient towards “different possibilities [that] appear on the horizon”, as one of our informants called it. CI practitioners typically notice several affordances simultaneously or even watch “alternatives attentively without using them”, as one informant dancer called it. Field awareness requires peripheral vision and, according to some dancers, non-canonical senses that expand a quasi-tactility beyond the body boundaries. This field awareness was called “spherical space” by CI founder Steve Paxton and refers to an “accumulated image gathered from several senses”. A spherical space of this kind is “the result of so many changes in spatial and kinesthetic orientation in a short time” [81]. Importantly, the concept of field awareness explains how creativity can have “partial sightedness” [82] and how dancers, accordingly, give direction to creativity, despite the irreducible role of exploration, playfulness, and chance discovery. Field awareness elucidates how dancers actively shape the possibility space of the dance. Dancers try “not to plan; but what I certainly do is to narrow down my options roughly”, as an informant expresses it. Field awareness provides a perceived horizon, which allows dancers to co-opt heuristics that “zoom in on a probable region of the solution space”, as creativity researcher Dietrich Haider calls it ([82] p. 901). Moreover, dancers strategically constrain this possibility space not only to make certain future more likely, but to affect how indeterminate the situation becomes as a whole (see Section 6.3).

To sum up, our observations on perceptual acuity clearly indicate that experienced dancers: (a) track and integrate multiple sources of information; (b) know which information sources to prioritize when; (c) use this information to select or rescale their actions in real time, or anyway as fast as nerve transduction allows; and (d) know how to “read” even novel situations based on this information [40]. The account that best describes all this is ecological theory [32,35,83,84,85,86], where continuous interpersonal coordination occurs because agents reciprocally respond to momentary affordances. The dancers’ real-time perceptual awareness signals adaptation needs, assistance requests, springboards into familiar synergies, and perhaps a hint of a crazy creative thing to try next. One basic creativity skill is to respond quickly to ad hoc affordances, while another skill is to actively sculpt, tweak, redirect, or rapidly “flip” them into a new configuration. As ecological theory predicts, what dancers perceive as afforded to them or their partner is encapsulated in invariants of the movement dynamics, balance, geometry, vectors, and all the other perceptual foci that we discovered (see above). As the father of affordance theory, James Gibson, would have said, the dancers’ “educated attention” allows them to read transient informational arrays arising from the engagement.

4.3. Organizing the Motor Repertoire for Flexibility

Moving from one “familiar place” to the next is not what CI is about. Dancers emphasize that they eschew using “ready-mades” and avoid chunky motor packages in general. As Nancy Stark Smith, a founder of CI, observes, “You can make a whole dance of very familiar moves. But you can also change it just a little bit to make it your own, to custom-make it in the moment—in the timing, phrasing, or the weight of it. It’s like practicing scales before you’re going to play” [87]. In fact, experienced dancers, time and again, note how they customize solutions and in doing so incorporate experiential traces from myriads of sources, which they co-assemble in real time.

To improvise effectively and come up with novel, yet functional movement material, it is imperative to organize one’s motor control system in a specific way which we term polysynthetic. Dancers must develop a strong capacity for variable cognitive (and motor) assembly. They must, figuratively speaking, come to freely play on the “keyboard” of CI-relevant dance parameters. In other words, dancers are faced with the challenge of assembling action in real time from a multi-dimensional array of motor sub-systems. We may analytically think of this ability as using multiple dynamic controllers pertinent to the current situation; dancers who improvise must scale and mix these controllers into fitting solutions and, even when the latter are unfamiliar, use active exploration skills and self-created feedback to “home in” on a properly balanced result.

We may link this to the theoretical notion of soft-assembly [88,89]. First, this implies that agents, instead of using pre-packaged movement units, operate flexibly within a field of constraints and synthesize actions from a set of dynamic primitives. Their motor control system must be “decompositionally” organized so that (semi-)independent movement parameters can be activated on demand. Agents must scale and orchestrate these primitives in concert. This requires some awareness of how parameters influence each other (and from what point on) when the dancers re-scale them. Finely decomposable repertoires allow myriad situated assemblies and almost unbounded creativity in the dance. An infinite range of compositional outcomes can emerge from a cleverly structured competence system such as this. Soft assembly gains further purchase for explaining interaction-based creativity in virtue of the notion’s deeply ecological nature: Authors who write on the topic emphasize that soft-assembling agents exploit the coupling with external dynamics, an idea that captures well what happens in CI. Dancers attain a highly reactive fit with situated constraints and ongoing movements by complementing what the partner does through appropriately scaled dynamic primitives. They minutely adapt to parametric changes in the other body, e.g., when the partner’s muscle tone during an acrobatic movement suddenly changes, they modulate their own movement accordingly. For viable collective synergies to arise “on-the-fly”, dancers must know how to balance collective parameters, e.g., the angle and amount of weight between two leaning bodies or the way force vectors run through their body when they lift someone. A third implication of soft-assembly for creativity is that there need not be any hardwiring of modules to tasks. Parts of the motor system may be used for different things in different contexts; inversely similar outcomes can be created in different ways.

4.4. Coordination Skills for Unplanned, Yet Complex Patterns

Joint creativity presupposes, as a basic skill, to coordinate complex collective forms that require perfect mutual timing and complementariness. Take the case of a lift of a partner onto one’s back, and then to the shoulders to spin him there. We had dancers dissect the small-scale structure of this and other sequences in thinking-aloud to understand its complexities. It turns out that the completion of the lift demands precise co-actions over three or four stages and partners must reciprocally provide green lights—“I’m safe and ready”, as one of our informants calls it—before continuing to the next stage. Tasks such as these are multi-phasic and path dependent. The final phase is only attainable after three prior actions.

There are many interaction researchers who argue that a keystone of complex coordination are shared task representations of “who does what when”, an implicit prior agreement (so-called planned coordination). Indeed, experiments on everyday actions such as joint object carrying show that short pre-agreed modules, albeit with fine-tuning potential, facilitate coordination [90,91,92]. Thus, from a naive viewpoint, this account would be tempting as an explanation of how well-timed complementary contributions in CI come about for collective forms such as lifts. The problem is that shared task representations are the very opposite of improvisation.

Are CI patterns such as lifts a case of planned coordination, or can they provide leeway enough to deserve the name “improvisation”, and if so how? Let us look at the phenomenological data: Our experts reported that planned coordination may be used by inexperienced dancers when their real-time skills are still undeveloped. In contradistinction, at their own more advanced level, multi-phasic or otherwise complex coordination becomes possible without implicitly agreeing beforehand on “who does what when”. After all, nothing commits them to doing the full lift. They remain ready for the situation to develop in many different ways. The lift can be converted to something different at certain junctures if one partner says “no”. Our data notably provide evidence that task planning in the narrow sense rarely happens. Even in scenarios such as lifts, dancers continue to “expect the unexpected”, albeit within narrower situational constraints. Consequently, they select motor commands at the shortest possible notice, as reflexes rather than as plans. Their motor system remains ready for surprises. Whatever anticipations of possible near-futures they might have, these anticipations remain non-priming at the motor level.

We found that the dancers’ ability to coordinate without strict planning builds on a combination of factors: First, they know they can embrace a real-time strategy since their dexterity provides enough reactivity to alleviate the need for motor anticipation. Second, once a lift begins, its biomechanics impose narrowed task constraints so skilled partners behave relatively predictably due to injury avoidance. Third, the situation logic itself hints at possible futures and provides a sense of field awareness, which they reported at least in lifts and other routine scenarios (see Section 4.2). This ability to “read” the situation provides a sense of the near futures the ongoing action is building up to. By perceiving the wider situated constraints (e.g., someone has both feet off the ground), dancers recognize slowly evolving aspects of the affordance landscape ([59], also see Section 2.2). In other words, aspects that cannot change abruptly in the next second provide crucial orientation. For example, dancers may be able to anticipate the role distribution into the near future if they are providing the support for a partner who is up in a lift. They know they will continue to be the support for about a second, irrespective of other details. Fourth, dancers understand the cumulative causal structure of sequences such as lifts and accept that “green lights” of the partner are functionally necessary at certain points to go further. Together, the last two factors—a grasp of the wider situation logic and of path dependencies—can provide the dancers with a roughly shared understanding of where they are and thus a constrained “horizon” despite indeterminacy.

All these orienting constraints are perceived in real time. Based on them, multiple scenarios can appear on a dancer’s inner radar concerning how actions complement each other and temporally mesh with the partner’s, albeit without premature commitment to any variant. The final say belongs to the real-time triggers, while recognition of possible contingencies readies dancers. Standing prepared for multiple futures could be interpreted as contingency sequences hovering in both dancers’ minds, hence possible co-action representations (“who does what when”) that are ready to kick in rapidly, but without priming the motor system prematurely. This model explains why a multi-timescale situation awareness is sufficient to coordinate complex tasks such as lifts. Thus, instead of prior agreements about the task specifics, experienced dancer partners are able to create finely fitting inter-body synergies on-the-fly. Planned coordination is not needed here. The synergies are emergently coordinated and devoid of real planning, whether they look like a familiar “ready-made” or create a novel pattern.

4.5. Creativity Techniques

To complement the picture, we now describe a set of techniques CI dancers use for creativity in the narrower sense. Creativity may take guidance from self-imposed task constraints or heuristics such as “avoid doing what comes to mind first”, “get off the beaten path/out of your own patterns”, “try to surprise your partner”, “surprise yourself”, or “try to reject offers when you can”. A similar heuristic that leads to novelty is to engage in purposeful variation and to court complexity:

There is kind of an intellectual risk or an intellectual engagement that is going on. Given it is physical and yet… I was messing constantly with how complex can I be in this moment. In how many different ways can I touch at one moment.

Improvisational creativity, at its core, involves accepting and working with whatever comes along. Dancers often emphasize how joyful “not knowing” what will happen next can be. Surprising emergence can even be courted on purpose: Uncertain, ambiguous, or even precarious zones are sought out where indeterminacy occurs, say, through a lack of physical support. Dancers take (reasonable) risks to experiment with ways of getting out of the situation. This “heightening the stakes”, as one informant calls it, jogs creativity. It challenges one’s reflexes and dexterity to rapidly find or create a resource. Dancers often mention how, for the sake of creative challenge, they relish difficult situations they could have avoided or aborted. For example, one of our participants mentioned a situation where it “takes really millisecond timing figuring out—am I being saved or am I saving?” Thus, creativity driven by external factors is invited. Similarly, a degree of provocation is held to be desirable for many dancers. Heightening the stakes in this sense depends on trusting the partner’s self-sufficiency and ability to fall safely. Another informant remarks that “joyful contact dancing is when you know, okay, the other person can look after herself, really physically and can maneuver out of various tricky situations”.

This echoes the improvisation literature where there is consensus about the importance of accepting risks [93,94]. Risk is something which improvisers use as an inspirational source for themselves or to challenge others to come up with creative solutions, as Miles Davis famously did [23,94]. For example, a recognized creativity heuristic in jazz is to immediately repair glitches by altering the wider context, where the glitch suddenly makes sense. Expressed differently: when one’s ideas fail in interaction and an instant repair or recontextualization is needed, creativity is stimulated. In one CI example that we observed, the partner failed to recognize an invitation and moved away so the first dancer ended up doing something awkward, but funny (the example will be reported in detail later and Figure 3 will show what the movement looks like). Moments such as these are not rejected, but embraced.

Dancers mention as a creativity technique that they enter regions with indeterminate biomechanical characteristics, such as tipping points. Indeterminacy can be actively favored, or, as a dancer says: “Where is the moment that neither one of us has a clue. […] That is a place I often go to. Where is the moment that we don’t know? It is not clear for either one of us what can happen.” Where the immediate future is unpredictable, creative challenges arise. In fact, dancers may actively tip the collective system to invite (not yet determined) creative adaptations. Notably, destabilizing an ongoing coordination pattern can lead to this. In one example we observed, a dancer altered his position and initiated a rocking motion. This motion grew to the point of making him unstable and receptive to external perturbations fed into his system by the partner. In a second example, the dancers jointly adapted and oscillated between support and non-support, resulting in a constant “disassembling and assembling” of balance. The moments when she was “off being supported […] [were] really short; immediately […] [she was] clicking back in”. This example suggests that a key skill is to find new structure in the indeterminate situation. Such brinkmanship is somewhat similar to soccer players who “ride the boundary between legality and illegality to gain a competitive advantage” [95] and to martial artists who explore a tipping point to find new dynamics [64].

It thus appears that a technique to stimulate creativity is to seek out the analogue of what dynamic systems theory (DST) refers to as metastable states [95,96,97,98]. In dancing, both the individual body and the interpersonal system can occupy a metastable position where agents are poised at the “edge” of different possible futures, and minimal nudges can tilt the dynamics either way. We see the same phenomenon in small improvisation experiments, where experts “stay in the zone” [99,100]. To paraphrase what CI experts report, interesting possibilities result when they gravitate towards this zone full of indeterminacy, yet pregnant with multiple futures. By lingering there, they empower collective self-organization dynamics and usable fluctuations (see Section 6.2).

4.6. Zoom Out

We have argued that dancers actively seek out stimulating situations, risks, challenges, and enter zones of indeterminacy. They react to self-stimulated challenges, but also stimulate the partner. They apply heuristics that constrain their own dancing to direct them away from the beaten path and to new regions of the action space. In this way, active strategies that reach slightly ahead in time are just as vital to creativity as rapid reactions to surprises and challenges. We may conclude that able improvisers actively sculpt or generate affordances that furnish creative “springboards”.

Apart from creativity techniques proper, dancers create conditions of possibility for flexible and variable movement improvisation [39]. To enable creative feats, dancers need to organize their bodies and relational parameters between them for action-readiness. They stay poised for novelty. Furthermore, improvisational creativity presupposes action skills that hand the dancers a polysynthetic, sufficiently flexible and wide repertoire. Finally, real-time creativity presupposes “educated attention” that supports rapid decision-making even in unfamiliar situations. As dancers monitor the ever-changing biomechanical constraints, they achieve momentary orientation as well as prospective field awareness about the range of possible continuations. The latter ability prepares them for nudging things in the general direction their creativity desires.

5. Results II: From Weakly to Radically Interactive Creativity

We have already introduced the notion that the ongoing engagement between the dancers, i.e., their coregulation, operates via a double loop of feedback and feedforward. From this reciprocal engagement, a momentary interactive milieu emerges that constrains and enables creativity, defines a field of affordances to select from, suggests springboards into new interpersonal synergies, or simply provides inspiration. We now investigate how these fundamental characteristics of the interaction relate to the dancers’ creativity.

5.1. A Taxonomic Criterion

We aim to bring together a couple of concise examples to delineate the spectrum of co-creation mechanisms that CI offers to the dancers. From a synoptic perspective, the data in our study suggest that in CI we are dealing with a continuum of weaker and stronger versions of interactive co-creation. These creativity types differ regarding the role and importance of ongoing interactivity. We distinguish, on a relatively broad spectrum, one pole where the collective milieu simply inspires and constrains creative ideas from a pole where the ongoing coupling dynamics and co-participation between dancers serve as the constitutive principle of generativity.

At the weakly interactive pole, we may still speak of an “internal” mode of creativity. An idea is prefigured in one dancer’s mind to create a potential fit to the situation, and the dancer tries to implement it. The act of creation is minimally planned, and reaches into the future by perhaps a second. These internal ideas sometimes can be followed through, but more frequently they need to be adapted as the situation has already changed slightly. Even when interactive adaptations occur, the generative act lies in the prior moment and in the mind of a single dancer.

At the radically interactive pole of the spectrum, dancers let creative patterns emerge fully through the on-going process. They avoid internal ideas that would reach ahead or anticipate what they or their partner might do. Primacy is given to participatory dynamics and emergence. This means that viable, yet unplanned interpersonal synergies are created in real-time. The dancers constantly explore, respond, and, in doing so, scaffold each other over time, rather than one dancer being strongly initiating. The processually extended “in between” of two dancers is the ontologically irreducible substrate of this type of co-creation. Self-organizing couplings become constitutive. This is a distinctive feature which more internal forms of creativity lack. In fact, the forward reaching intentions of an internally creative person would actively deselect or override many fertile micro-couplings that arise in the “in between” of two dancers.

5.2. Minimal Entanglement and Solicited/Enforced Cooperation

In some cases, dancers report that internal creativity scarcely needs interactive adaptation to begin with. First, this happens in dancing out of contact or, in contact, when some minor flourish has little impact on the partner. Secondly, dancers can also follow their ideas freely at moments where the partner is accommodating or implicitly agrees to follow, e.g., when a dancer says “there was a moment when [he] kind of surrendered to my idea in terms of: let’s see what she is doing, and let’s accommodate that doing”.

Another option to try to accommodate your own ideas is by manipulating the partner. For example, one of our experts with an Aikido background applied a wrist lever to force the partner into a fall (which the partner then creatively converted into a rotational figure on the ground). Besides manipulating, dancers may invite partners to share an idea of theirs, e.g., by ostentatiously extending the outstretched hand, as we observed during one of our think-alouds. Finally, dancers may create situations that offer a very limited field of affordances to the partner and will likely nudge his or her response into the desired direction.

5.3. Internal Creation Mechanisms

At the far end of the co-creation spectrum, an internal idea can creatively modulate familiar movement material: creatively adapting prototypes or varying the structure of known exemplars has been documented in musical improvisation [101]. In CI, working with “familiar places” such as handstands, lifts flips, or weight support in table position can proceed in a similar manner. The creative part is how the dancers tune the rhythm, spacing, dynamics, or the tactile and kinesthetic quality to the situation. A dancer commented that as soon as two people move dynamically “it is to a tremendous degree also a question of what the angles in space are precisely like […] changes in the minutiae […] have different effects in each case”. (In these cases, the creative part lies in the “how”, while the movement material itself, the “what”, can be very commonplace). Conversely, when a ready-made concerns only one body, it can combine creatively with the partner’s actions into larger patterns.

A notch up on the creativity scale, new movement material is created. This can be as simple as using an easily done, but bizarre movement such as sticking the head underneath the partner’s shirt in order to be provocative. Creative material such as this may arise through analogies from situations such as hiding under a blanket as a child. With a dancer who is drawn to musicality, creative material can arise from a rhythm he or she pursues for a time, or a dancer may be intrigued by particular spatial variations. Since these ideas are constrained they can often only come alive fully if the partner actively picks up on the idea. In one particular case, the partner began to mimic a rhythm until dancers were rhythmically reversing roles sitting on top of each other.

Another notch up the scale, generative mechanisms from the creativity literature, can be brought into play, of which we now discuss several: The first mechanism is to recombine aspects from different familiar dance scenarios. To illustrate, we observed dancers who creatively reversed roles in the commonplace “body-surfing” scenario, where a dancer is situated on the floor and the partner in a perpendicular position on top. Usually, the lower dancer will transport the upper dancer through space by rolling across the floor. A more creatively inclined dancer in the top position, however, need not follow the momentum of the partner below. He or she can instead approach things the other way around by locking hands or feet to the floor and then moving, stopping, or redirecting the bottom dancer with his or her body center. To provide another example of how elements are creatively combined, dancers might combine a handstand with a backward movement (which is atypical and needs great skill as well as overcoming fear reflexes). In such examples, dancers mentally “mesh” known action affordances into something new (see Glenberg and Robertson [102], who noted that a shirt stuffed with leaves can serve as a pillow, if someone combines these elements after simulating their fit mentally). A somewhat related classical creativity mechanism that dancers report is grafting a familiar element to a new context. This can happen by mimicking gestures and movements or quoting other dances.

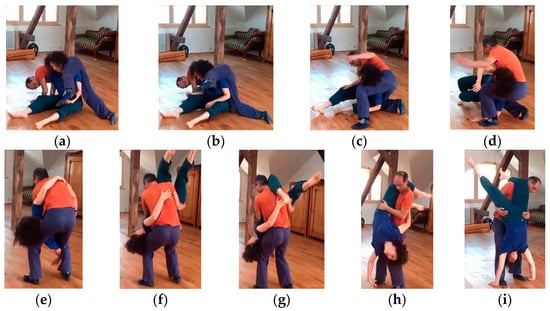

We may also illustrate the creativity mechanism of filling a task’s functional slots in unconventional ways: We observed a dancer (Figure 1) who replaced the canonical body part used for supporting the partner’s legs, namely the hands, to an unexpected option: his face. This solution is unusual, but fits perfectly into the dynamics since the face was already in position for giving its weight.

Figure 1.

Replacing hand support with face support for partner’s legs: (a) hand-to-foot support; (b) face-to-foot support.

Sometimes, even full-scale analogical mappings occur. For example, a dancer said he wanted to imply a metaphorical meaning by ostentatiously falling into the partner and hereby suggest the act of “falling in love”. In another example, two dancers strode forward hand in hand and bowed like in a baroque minuet. In this way, dancers may on occasion create entire narratives in an analogical thought-space. In this particular case, only the dancer who was leading at the movement was creating this narrative, while the partner was unaware of it and focused on following without losing contact. Interestingly, however, internally created narratives originating in one dancer’s mind may be picked up on and upheld by the partner. For example, in another duet, two female dancers evoked a dominance- and eroticism-imbued story through a caress with one partner lying below the other (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Exploring emotional bounds.

To recap, internally creative CI dancers envisage a new pattern a fraction of second before trying to implement it. They do so by mentally simulating the idea to see if it is roughly functional [82], for instance by “meshing” affordances. The apparent cost of this creative strategy is that, during execution, something awkward happens because the partner’s concurrent actions are mismatched. Therefore, internally creative dancers are well advised to ensure partner compliance by implicit assistance, invitation, manipulation or nudging. Otherwise, they will probably need to adapt, redirect, or even abort their internal idea. A dancer concisely explained what the risks of fully specified movement intentions are: “The more definite imagination I put into it, the more likely I will get a no, because it will not correspond to your ideas”. In a striking example of this, a dancer experienced an awkward moment because she had over-committed herself to an idea of doing a small lift (Figure 3). She had assumed her partner was already going along with her idea, but in fact failed to communicate her invitation fully. The dancer had sensed a pre-affordance of sorts, but the lift then never got off the ground, because the all-important main affordance, the adequate support from the partner’s hips, was missing. She had interpreted the incipient dynamic as a shared preparation for her preferred co-action, while her partner felt no invitation. She remained unaware of this failure to communicate, nor did she attempt a repair. Our discussion of the event actually revealed that, if she had focused on the point where their bodies were to touch and had gauged the geometry, she could probably have corrected the lacking invitation on-the-fly. Instead of a late adjustment of this sort, she just stuck with her initial idea longer than was afforded by her partner’s actions. She commented that her failure had happened due to having focused too intensely on the lingering image of her desired idea.

Figure 3.

Unsuccessful lift.

5.4. Semi-Specific Ideas, Interactively Fleshed Out

Some internal CI ideas are inherently adaptable to the emergent dynamics with a partner (and thus keep the demonstrated dangers of over-commitment at bay). Many familiar dance techniques, even when a person envisages the idea to do them in advance, provide a good deal of leeway to begin with. Often, the reason is that a technique’s implementation details are not specified, e.g., in “sloughing” or creating a “rolling point” across the partner’s body. These techniques merely prescribe a general sort of control law, a simple behavioral algorithm that is defined relative to a collective variable, such as how a rolling point of contact moves along the partner’s body and at what angle pressure from one’s own body is directed to this point. This leaves open many paths along which to try this and any number of ways in which the limbs or torso implement the movement. In CI, the dancers’ applied knowledge of numerous familiar dance techniques revolves around broadly defined action categories, which follow an adaptable control heuristic or a general interaction principle.

In fact, even when it is not a familiar technique dancers have in mind, they may use internally generated ideas in adaptable ways: Frequently, a person envisages mere constraints on movement rather than a fully elaborated action pattern. The dancer specifies one selected parameter but leaves most other aspects open. The dancer may in fact reckon with dynamic specification through the interaction itself to flesh the other aspects out. Cognitively, such idea material comprises what Andreas Engel calls directives [103], rather than plans. In our data, many directives specify a particular biomechanical function, but not its implementation. Recall the earlier example where the face touches the partner’s foot (Figure 1). Here, the intended function was to support the lying partner’s legs, and to create a stable arc between their bodies. The dancer shifted rapidly from supplying the support through his hands to supplying it with his face. Apparently, he had not committed himself to a specific motor plan in advance, but was following ensuring the arc’s architecture in whatever way possible. His partial openness regarding means allowed him to embrace a rather uncommon, but perfectly functional option that the interaction presented him with. The perhaps most frequent case of directive-like internal ideas are general dance “scores” or thematic interests that impose one particular constraint, but leave enormous leeway in all other respects, e.g., intending “to experiment with relationality without touching the partner”. A typical CI score might “fixate” a particular biomechanical parameter for 20 or 30 s, such as keeping pelvises opposite or the interpersonal distance at a particular range. This self-imposed constraint allows the dancer to flexibly exercise all other degrees of freedom. With sufficient experience, almost any external dynamics, especially anything the partner may be concurrently up to, can be accommodated without violating a creative intention of a score. (Of course, the more parameters a dancer constrains in advance the greater the challenge and risk of mismatch with the partner.)

Another way to remain adaptable is to creatively plan a relatively specific initial action, but to keep the later stages of execution flexible enough to incorporate partner feedback. For example, a dancer decided to flip her pelvis across a sitting partner’s bent back (Figure 4). The details only became clear after momentum had already been generated, so the dancer on top had to adapt to how the partner moved the back (in terms of directional trajectory, contact point, and amount of energy).

Figure 4.

Back flipping.

In a related example, a dancer has envisaged his first impulse, but left later details open. Specifically, he reported that he was trying to find means to respond to a self-created challenge to test his own dexterity by letting his partner fall backwards and then quickly trying to find a way to catch her in time (Figure 5). His adaptability was called for too, as it turned out that anything beyond a minimal version of his original plan would have endangered his partner.

Figure 5.

Self-experiment: (a) let the partner fall; and (b) catch them.

To sum all this up, there is a broad category of ideation processes in CI that combine aspectual internal ideas with interactive specification of detail when feedback from the partner (or from one’s own actions, for that matter) arrives. This frequent creative strategy uses intentions that reach ahead in time, but eschews fully specified ready-mades and prefers something more flexible instead. Combining partial constraint settings and leaving many other degrees of freedom open to interactive tuning is inherently “improvisation-friendly” (see Section 6.4).

5.5. Elaborating, Echoing Motifs, and Body Memory

In a certain context, we may also speak of (partly) internal creativity when dancers pick up on aspects of the interaction dynamics to internally develop this further into new creative material. What has happened in the interaction so far may provide a creative “springboard” [104] or material to actively elaborate. The mechanisms of creative elaboration are recognized in different fields of esthetic creativity, including poetry [105]. In the CI context, we can apply the notion of elaboration to encompass anything from movement motifs experienced the night before down to ongoing physical impulses that inspire an idea.

In micro-scale elaboration, an internal idea is developed by moulding an active physical impulse. In one of the instances we observed, an arm-hooking action occurred with an intention that “was incidental, and then I used it more intentionally”. For instance, an impulse by the partner who has almost run its course can suggest a particular movement direction. As this category may come close to radically interactive creativity (see Section 5.6, Section 5.7 and Section 5.8), under this rubric, we restrict ourselves to cases of mere inspiration with independent execution, and leave synergistic biomechanics for later. To exemplify a merely inspirational case, a dancer “converted” a brief kicking impulse received from the partner into multiple rotations, but carried them out independently. Even if she added to the collective dynamic pattern in an esthetic sense, in a biomechanical sense, she acted more on the partner’s inspiration than to complement a physical synergy.

Much other creative elaboration happens after the inspiring physical impulse has run its course: At the temporal meso-scale, CI dancers like to speak of “compositional awareness”, a readiness to elaborate a lingering trace of perceptual memories. Dancers explain compositional dancing as involving a reflexive awareness of dance situations, for instance with respect to geometry, and a willingness to comment on, or to subvert them. Shared motifs can be repeatedly “quoted” or “echoed”, e.g., an earlier arm gesture gets mirrored in the reverse direction. Compositional dancing adds spice and dimensionality the basic operational mode of CI, as a dancer commented. It is often a momentary affordance that brings associated material and motifs back. More generally, certain imprints of moves, sensorial qualities, or themes can be, as a dancer said, “are more easily accessible to the nervous system” because they resonate with body memory [78,106,107]. Some reports from dancers would even suggest that they have a rich body-memory “sketchpad” on which they accumulate impressions.

At the highest timescale dancers can take inspiration across longer period of interaction, again in the form of “quoting” or “echoing” accumulated imprints from the present encounter or even in the form of resonating experiences from before this dance. To exemplify the latter case, our participants report having been primed by memories of riding on a tram earlier or by memories of last night’s CI teaching session, or by recollections of repeating themes with this particular partner.

5.6. “Survival” Creativity