Traumatic Brain Injury, Boredom and Depression

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.2.1. Boredom Proneness

2.2.2. Depression

| Group (N) | Age M (SD) | Age range | Years post injury | ACRM Criteria | BPS score M (SD) | Internal Scale M (SD) | External Scale M (SD) | BDI-II score M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (88) | 23 (1.4) | 17–51 | NA | NA | 93.42 (28.31) | 26.58 (15.3) | 64.51 (19.68) | 11.53 (11.62) |

| Mild TBI (38) | 24 (9) | 18–54 | GCS 13–15 w/in 30 mins LOC < 30 mins | 101.21 (23.12) | 30.31 (4.14) | 61.41 (19.51) | 10.58 (9.87) | |

| Mod-to-SevTBI (14) | 36 (12.1) | 18–56 | GCS ≤ 12 LOC > 30 mins | 106.21 (21.93) | 34.51 (8.12) | 68.43 (11.32) | 13.36 (9.96) | |

| Pt1 | 42 | 20 | Coma several weeks | 100 | 35 | 63 | 0 | |

| Pt2 | 36 | 30 | Coma several months | 75 | 28 | 50 | 4 | |

| Pt3 | 40 | 20 | Coma 6 weeks | 140 | 48 | 89 | 30 | |

| Pt4 | 56 | 30 | LOC = 40 mins | 100 | 16 | 11 | 8 | |

| Pt5 | 25 | 6 | Coma 6 weeks | 119 | 28 | 81 | 18 | |

| Pt6 | 34 | 14 | Coma 6 weeks | 123 | 39 | 18 | 16 | |

| Pt7 | 18 | 2 | LOC, PTA 2 weeks | 116 | 36 | 11 | 11 | |

| Pt8 | 54 | 10 | Coma 2 weeks | 80 | 21 | 52 | 10 | |

| Pt9 | 23 | 12 | LOC 2 hours | 143 | 35 | 102 | 32 | |

| Pt10 | 39 | < 1 | LOC, PTA 8 hours | 113 | 38 | 14 | 22 | |

| Pt11 | 39 | 2 | “Brief” LOC | 72 | 28 | 42 | 8 | |

| Pt12 | 19 | 10 | LOC unknown length | 104 | 31 | 63 | 20 | |

| Pt13 | 30 | 11 | Coma 2 weeks | 91 | 40 | 49 | 3 | |

| Pt14 | 49 | 2 | Collapsed with seizure | 111 | 49 | 61 | 5 |

3. Results

3.1. Boredom Proneness

3.2. Depression

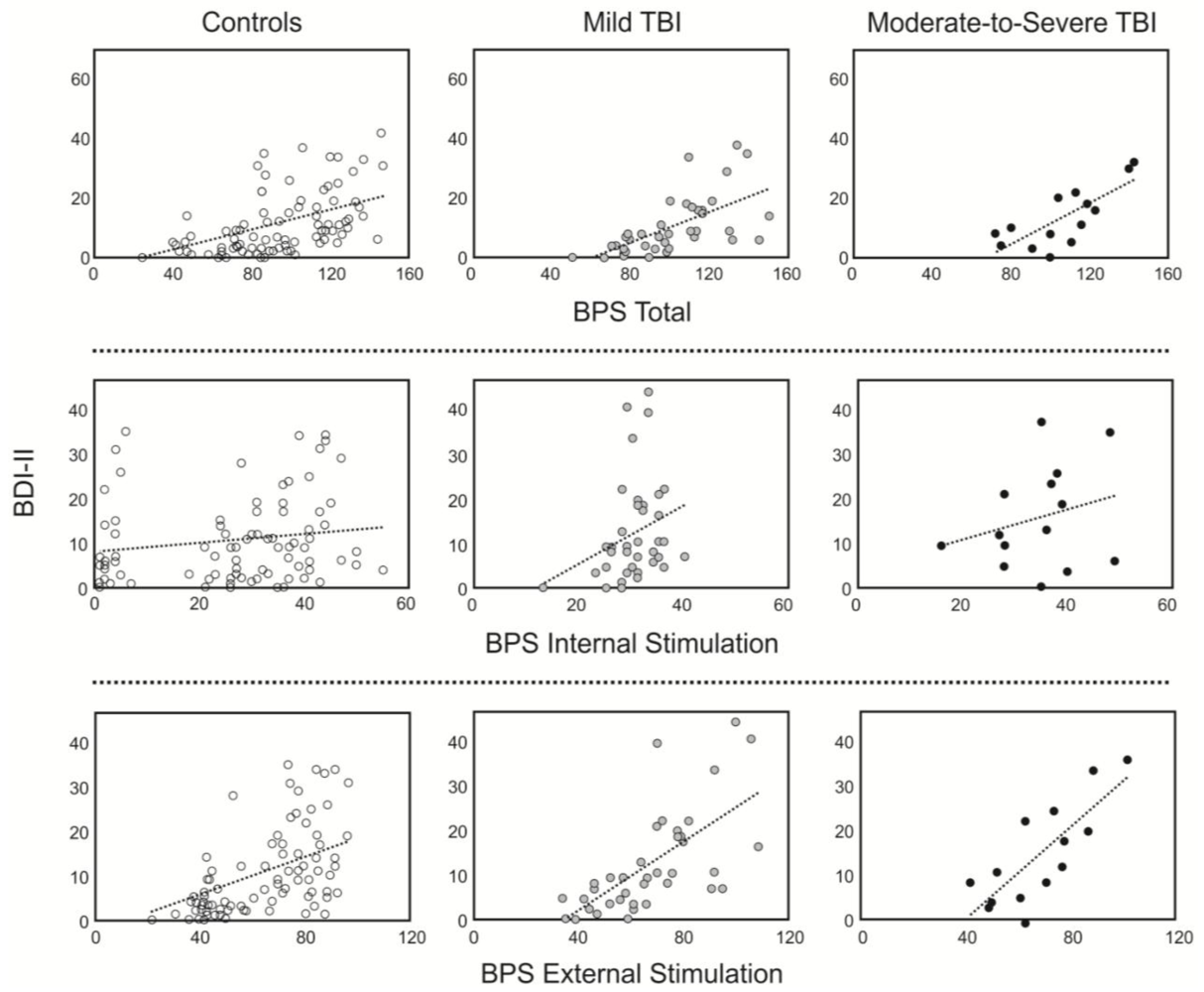

3.3. Relationship between Boredom and Depression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Al-Adawi, S.; Powell, J.H.; Greenwood, R.J. Motivational deficits after brain injury: A neuropsychological approach using new assessment techniques. Neuropsychology 1998, 12, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chervinsky, A.B.; Ommaya, A.K.; de Jonge, M.; Spector, J.; Schwab, K.; Salazar, A.M. Motivation for traumatic brain injury rehabilitation questionnaire (MOT-Q): Reliability, factor analysis and relationship to MMPI-2 variables. Arch. Clin. Neuropsych. 1998, 13, 433–446. [Google Scholar]

- Mathias, J.L.; Beall, J.A.; Bigler, E.D. Neuropsychological and information processing deficits following mild traumatic brain injury. J. Int. Neuropsych. Soc. 2004, 10, 286–297. [Google Scholar]

- Seel, R.T.; Kreutzer, J.S. Depression assessment after traumatic brain injury: An empirically based classification method. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehab. 2003, 84, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, R.; Sundberg, N.D. Boredom proneness-The development and correlates of a new scale. J. Perso. Assess. 1986, 50, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, Y.; Eastwood, J.; LaGuardia, J.; Danckert, J. Boredom: An emotional experience distinct from apathy, anhedonia or depression. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 30, 646–665. [Google Scholar]

- Vodanovich, S.J. Psychometric measures of Boredom: A review of the literature. J. Psychol. 2003, 137, 569–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkovsky, E.; Merrifield, C.; Goldberg, Y.; Danckert, J. Exploring the relationship between boredom and sustained attention. Exp. Brain Res. 2012, 221, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melton, A.M.A.; Schulenberg, S.E. A confirmatory factor analysis of the boredom proneness scale. J. Psychol. 2009, 143, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenson, R.R. Apathetic and agitated boredom. Psychoanal. Q. 1951, 20, 346–347. [Google Scholar]

- Cheyne, J.A.; Carriere, J.S.A.; Smilek, D. Absent-mindedness: Lapses of conscious awareness and everyday cognitive failures. Conscious. Cognit. 2006, 15, 578–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastwood, J.D.; Frischen, A.; Fenske, M.J.; Smilek, D. The unengaged mind: Defining boredom in terms of attention. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 7, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keeffe, F.M.; Dockree, P.M.; Moloney, P.; Carton, S.; Robertson, I.H. Characterising error-awareness of attentional lapses and inhibitory control failures in patients with traumatic brain injury. Exp. Brain Res. 2007, 180, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dockree, P.M.; Bellgrove, M.A.; O’Keeffe, F.M.; Moloney, P.; Aimola, L.; Carton, S.; Robertson, I.H. Sustained attention in traumatic brain injury (TBI) and healthy controls: Enhanced sensitivity with dual-task load. Exp. Brain Res 2006, 168, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dockree, P.M.; Kelly, S.P.; Roche, R.A.P.; Hogan, M.J.; Reilly, R.B.; Robertson, I.H. Behavioural and physiological impairments of sustained attention after traumatic brain injury. Cognit. Brain Res. 2004, 20, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, I.H.; Manly, T.; Andrade, J.; Baddeley, B.T.; Yiend, J. ‘Oops!’: Performance correlates of everyday attentional failures in traumatic brain injured and normal subjects. Neuropsychologia 1997, 35, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, M.B.; Burke, D.T.; O’Neil-Pirozzi, T.; Goldstein, R.; Jacob, L.; Kettell, J. Cutoff score on the apathy evaluation scale in subjects with traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury 2002, 16, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II; The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- DeCoster, J. Applied Linear Regression Notes set 1. Available online: http://www.stat-help.com/notes.html (accessed on 1 September 2012).

- Theobald, D.E.; Kirsh, K.L.; Hotsclaw, E.; Donaghy, K.; Passik, S.D. An open label pilot study of citalopram for depression and boredom in ambulatory cancer patients. Palliative Support. Care 2003, 1, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, R.; Duffy, J.D.; Pivovarnik, A. Prevalence of apathy following head injury. Brain Injury 1998, 12, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregório, G.W.; Gould, K.R.; Spitz, G.; van Heugten, C.M.; Ponsford, J.L. Changes in Self-Reported Pre- to Post-injury Coping Styles in the First 3 Years after Traumatic Brain Injury and the Effects on Psychosocial and Emotional Functioning and Quality of Life. J. Head Trauma Rehab. 2013, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, T.; Hoffman, J.M.; Pretz, C.; Kennedy, R.; Clark, A.N.; Brenner, L.A. A Longitudinal study of major and minor depression following traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2012, 93, 1343–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seel, R.T.; Kreutzer, J.S.; Rosenthal, M.; Hammond, F.M.; Corrigan, J.D.; Black, K. Depression after traumatic brain injury: A National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Model Systems multicenter investigation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2003, 84, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; de Beurs, D.P.; van Spijker, B.A.; Berking, M.; Andersson, G.; Kerkhof, A.J. The effects of psychotherapy for adultdepressionon suicidality andhopelessness: A systematic reviewand meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 144, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryce, C.R.; Azzinnari, D.; Spinelli, S.; Seifritz, E.; Tegethoff, M.; Meinlschmidt, G. Helplessness: A systematic translationalreviewof theory and evidence for its relevance to understanding and treating depression. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 132, 242–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, N.S.; Martell, C.R.; Dimidjian, S. Behavioral Activation for depression: Returning to contextual roots. Clin. Psych. Sci. Prac. 2001, 8, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, L.K.; Naranjo, C.; Graham, S.J.; Herrmann, N.; Mayberg, H.S.; Hevenor, S.; Busto, U.E. Functional neuroanatomical substrates of altered reward processing in a major depressive disorder revealed by a dopaminergic probe. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 2005, 62, 1228–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kringelbach, M.L. The human orbitofrontal cortex: Linking reward to hedonic experience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005, 6, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Goldberg, Y.; Danckert, J. Traumatic Brain Injury, Boredom and Depression. Behav. Sci. 2013, 3, 434-444. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs3030434

Goldberg Y, Danckert J. Traumatic Brain Injury, Boredom and Depression. Behavioral Sciences. 2013; 3(3):434-444. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs3030434

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoldberg, Yael, and James Danckert. 2013. "Traumatic Brain Injury, Boredom and Depression" Behavioral Sciences 3, no. 3: 434-444. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs3030434

APA StyleGoldberg, Y., & Danckert, J. (2013). Traumatic Brain Injury, Boredom and Depression. Behavioral Sciences, 3(3), 434-444. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs3030434