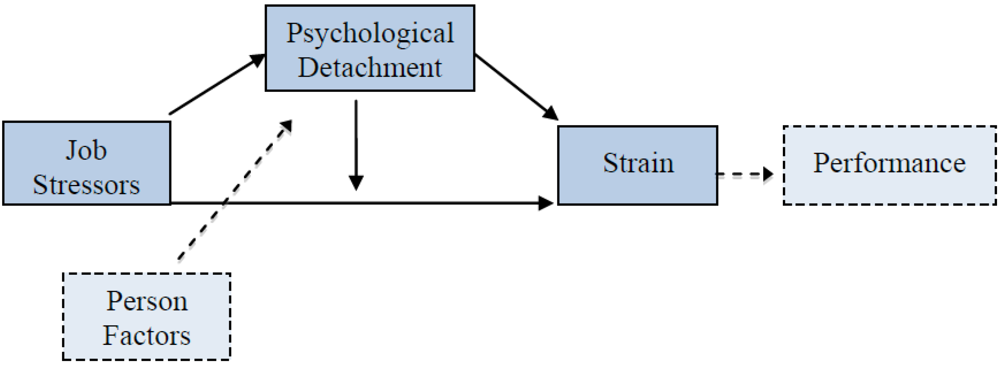

Psychological Detachment in the Relationship between Job Stressors and Strain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Job Demands

2.2.2. Stress

2.2.3. Cognitive Failures

2.2.4. Satisfaction with Life

2.2.5. Psychological Detachment

2.2.6. Control Variables

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Tests of Mediation

3.1.1. Perceived Stress as the Outcome

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | --- | --- | ||||||||||

| 2. Program | --- | --- | 0.07 | |||||||||

| 3. Deadline | --- | --- | 0.02 | −0.73 ** | ||||||||

| 4. Academic work weekdays | 30.71 | 12.07 | 0.16 * | −0.20 ** | −0.09 | |||||||

| 5. Academic work weekends | 6.21 | 3.88 | −0.00 | 0.27 ** | −0.16 * | 0.46 ** | ||||||

| 6. Negative affectivity | 1.99 | 0.57 | 0.11 | 0.13 | −0.15 | 0.03 | 0.19 * | |||||

| 7. Job demands | 3.16 | 0.60 | 0.04 | 0.44 ** | −0.35 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.35 ** | ||||

| 8. Detachment | 2.05 | 0.81 | −0.09 | −0.30 ** | 0.23 ** | −0.35 ** | −0.49 ** | −0.27 ** | −0.52 ** | |||

| 9. Stress | 1.82 | 0.66 | 0.29 ** | 0.26 ** | −0.24 ** | 0.14 | 0.20 ** | 0.67 ** | 0.48 ** | −0.41 ** | ||

| 10. Cognitive failures | 1.79 | 0.47 | 0.03 | 0.08 | −0.07 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.54 ** | 0.36 ** | −0.20 ** | 0.55 ** | |

| 11. Life satisfaction | 4.83 | 1.14 | 0.15 | −0.09 | 0.14 | 0.01 | −0.12 | −0.40 ** | −0.21 ** | 0.21 ** | −0.44 ** | −0.37 ** |

| Perceived Stress | Cognitive Failures | Satisfaction with Life | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SEB | t | B | SEB | t | B | SEB | t | |

| Control variables | |||||||||

| Gender | 0.352 | 0.089 | 3.97 *** | 0.008 | 0.072 | 0.114 | 0.407 | 0.179 | 2.278 * |

| Deadline | −0.108 | 0.089 | −1.22 | 0.053 | 0.073 | 0.727 | 0.104 | 0.180 | 0.575 |

| Acad. Work weekends | −0.011 | 0.013 | −0.904 | −0.007 | 0.010 | −0.676 | 0.003 | 0.026 | 0.118 |

| Direct effect ofJob Demands on Detachment | −0.476 | 0.095 | −5.00 *** | −0.476 | 0.095 | −5.00 *** | −0.476 | 0.095 | −5.00 *** |

| Direct effect ofDetachment onoutcome | −0.177 | 0.066 | −2.69 ** | −0.018 | 0.054 | −0.341 | 0.268 | 0.133 | 2.017 * |

| Total effect of Job Demands on outcome | 0.472 | 0.082 | 5.75 *** | 0.0312 | 0.066 | 4.756 *** | −0.332 | 0.164 | −2.020 * |

| Effect of Job Demands on outcome after adjustment forDetachment | 0.388 | 0.086 | 4.49 *** | 0.304 | 0.071 | 4.298 *** | −0.205 | 0.175 | −1.171 |

| Model summary | |||||||||

| R2 | 0.337 | 0.135 | 0.097 | ||||||

| (R2adj) | 0.317 | 0.109 | 0.069 | ||||||

| p | < 0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.0046 | ||||||

3.1.2. Cognitive Failures as the Outcome

3.1.3. Satisfaction with Life as the Outcome

3.1.4. Additional Control for Negative Affectivity

3.2. Test of Moderation

3.2.1. Perceived Stress as the Outcome

3.2.2. Cognitive Failures as the Outcome

| Perceived stress | Cognitive failures | Satisfaction with life | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SEB | t | B | SEB | t | B | SEB | t | |

| Control variables | |||||||||

| Gender | 0.354 | 0.090 | 3.917 *** | 0.010 | 0.074 | 0.136 | 0.430 | 0.183 | 2.357 * |

| Deadline | −0.107 | 0.090 | −1.193 | 0.54 | 0.073 | 0.733 | 0.114 | 0.181 | 0.630 |

| Academic work weekends | −0.011 | 0.013 | −0.894 | −0.007 | 0.010 | ˗0.669 | 0.004 | 0.026 | 0.144 |

| Job Demands | 0.388 | 0.087 | 4.475 *** | 0.304 | 0.071 | 4.286 *** | −0.203 | 0.175 | −1.163 |

| Detachment | −0.175 | 0.068 | −2.579 * | −0.017 | 0.055 | −0.302 | 0.288 | 0.137 | 2.108 * |

| Job demands × Detachment | 0.013 | 0.085 | 0.154 | 0.009 | 0.070 | 0.126 | 0.112 | 0.172 | 0.650 |

| Model Summary | |||||||||

| R2 | 0.337 | 0.136 | 0.099 | ||||||

| (R2adj) | 0.313 | 0.104 | 0.066 | ||||||

| p | 0.878 | 0.900 | 0.517 | ||||||

3.2.3. Satisfaction with Life as the Outcome

3.2.4. Additional Control for Negative Affectivity

3.3. Discussion

3.3.1. Limitations of the Study

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Meijman, T.F.; Mulder, G. Psychological Aspects of Workload. In Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology, 2nd ed.; Drenth, P.J.D., Thierry, H., de Wolff, C.J., Eds.; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 1998; Volume 2, Work psychology; pp. 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Bayer, U.V. Switching of mentally: Predictors and consequences of psychological detachment from work during off-job time. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S. Recovery from Fatigue: The Role of Psychological Detachment. In Cognitive Fatigue: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Current Research and Future Applications, 1st ed.; Ackerman, P.L., Ed.; APA Sciences Volumes: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 253–268. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.T.; Ashforth, B.E. A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; LePine, J.A.; LePine, M.A. Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, Turnover intention, Turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 438–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siltaloppi, M.; Kinnunen, U.; Feldt, T. Recovery experiences as moderators between psychosocial work characteristics and occupational well-being. Work Stress 2009, 23, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Fritz, C. Recovery experience questionnaire: Development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 204–221. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnentag, S.; Kruel, U. Psychological detachment from work during off-job time: The role of job stressors, Job involvement, and recovery-related self-efficacy. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2006, 15, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, C.; Yankelevich, M.; Zarubin, A.; Barger, P. Happy, Healthy, And productive: The role of detachment from work during nonwork time. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Kuttler, I.; Fritz, C. Job stressors, Emotional exhaustion, and need for recovery: A multi-source study on the benefits of psychological detachment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 76, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, A.; Pastor, J.C.; Sanz-Vergel, A.; Garrosa, E. The moderating effects of psychological detachment and thoughts of revenge in workplace bullying. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2009, 46, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Binnewies, C.; Mojza, E.J. Staying well and engaged when demands are high: The role of psychological detachment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Mayo, M.; Sanz-Vergel, A.I.; Geurts, S.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, A.; Garrosa, E. Effects of work-family conflict on employees’ well-Being: The moderating role of recovery strategies. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, Strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, K.; Elo, A.-L.; Skogstad, A.; Dallner, M.; Gamberale, F.; Hottinen, V.; Knardahl, S.; ∅rhede, E. User’s Guide for the QPSNordic: General Nordic Questionnaire for Psychological and Social Factors at Work; No. TemaNord 2000:603; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Williamson, G. Perceived Stress in a Probability Sample of the United States. In The Social Psychology of Health: Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology; Spacapan, S., Oskamp, S., Eds.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, B. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, D.E.; Cooper, P.F.; Fitzgerald, P.; Parkes, K.R. The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) and its correlates. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 1982, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allvin, M.; Aronsson, G.; Hagström, T.; Johansson, G.; Lundberg, U. Gränslöst arbete: Socialpsykologiska perspektiv på det nya arbetslivet; Liber: Stockholm, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, T.; Johansson, G.; Kylin, C. Residence in the social ecology of stress and restoration. J. Soc. Issues 2003, 59, 611–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Tyrell, D.A.J.; Smith, A.P. Negative life events, perceived stress, negative affect, and susceptibility to the common cold. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrecht, M.; Hextall, J.; Kirtley, L.G.; Taylor, A.; Dyson, M.; Weinman, J. Perceived stress and cortisol levels predict speed of wound healing in healthy male adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2004, 29, 798–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiran, N.; Israeli, A.; Levi, H.; Grafi, R. Individual differences in self-reported cognitive failures: The attention hypothesis revisited. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1994, 17, 727–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J.C.; Vodanovich, S.J. Can accidents and industrial mishaps be predicted? Further investigation into the relationship between cognitive failure and reports of accidents. J. Bus. Psychol. 2003, 17, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Zapf, D.; Chen, P.Y.; Frese, M. Why negative affectivity should not be controlled in job stress research: Don’t throw out the baby with the bath water. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Meth. 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnentag, S.; Binnewies, C.; Mojza, E.J. Did you have a nice evening? A day-level study on recovery experiences, sleep, and affect. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Kylin, C.; Johansson, G. The telework tradeoff: Stress mitigation vs. constrained restoration. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2007, 56, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, U.; Lindfors, P. Psychophysiological reactions to telework in female and male white-collar workers. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2002, 7, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondo, D.M.; Carlson, D.S.; Kincaid, J.F. Coping with multiple dimensions of work-family conflict. Pers. Rev. 2003, 32, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Safstrom, M.; Hartig, T. Psychological Detachment in the Relationship between Job Stressors and Strain. Behav. Sci. 2013, 3, 418-433. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs3030418

Safstrom M, Hartig T. Psychological Detachment in the Relationship between Job Stressors and Strain. Behavioral Sciences. 2013; 3(3):418-433. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs3030418

Chicago/Turabian StyleSafstrom, My, and Terry Hartig. 2013. "Psychological Detachment in the Relationship between Job Stressors and Strain" Behavioral Sciences 3, no. 3: 418-433. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs3030418

APA StyleSafstrom, M., & Hartig, T. (2013). Psychological Detachment in the Relationship between Job Stressors and Strain. Behavioral Sciences, 3(3), 418-433. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs3030418