The Impact of Perceptual Load and Distractors’ Perceptual Grouping on Visual Search in ASD

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Advantages of Visual Search in ASD

1.2. Perceptual Load and Perceptual Grouping in Visual Search in ASD

1.3. Factors Influencing Asymmetry in Visual Search

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

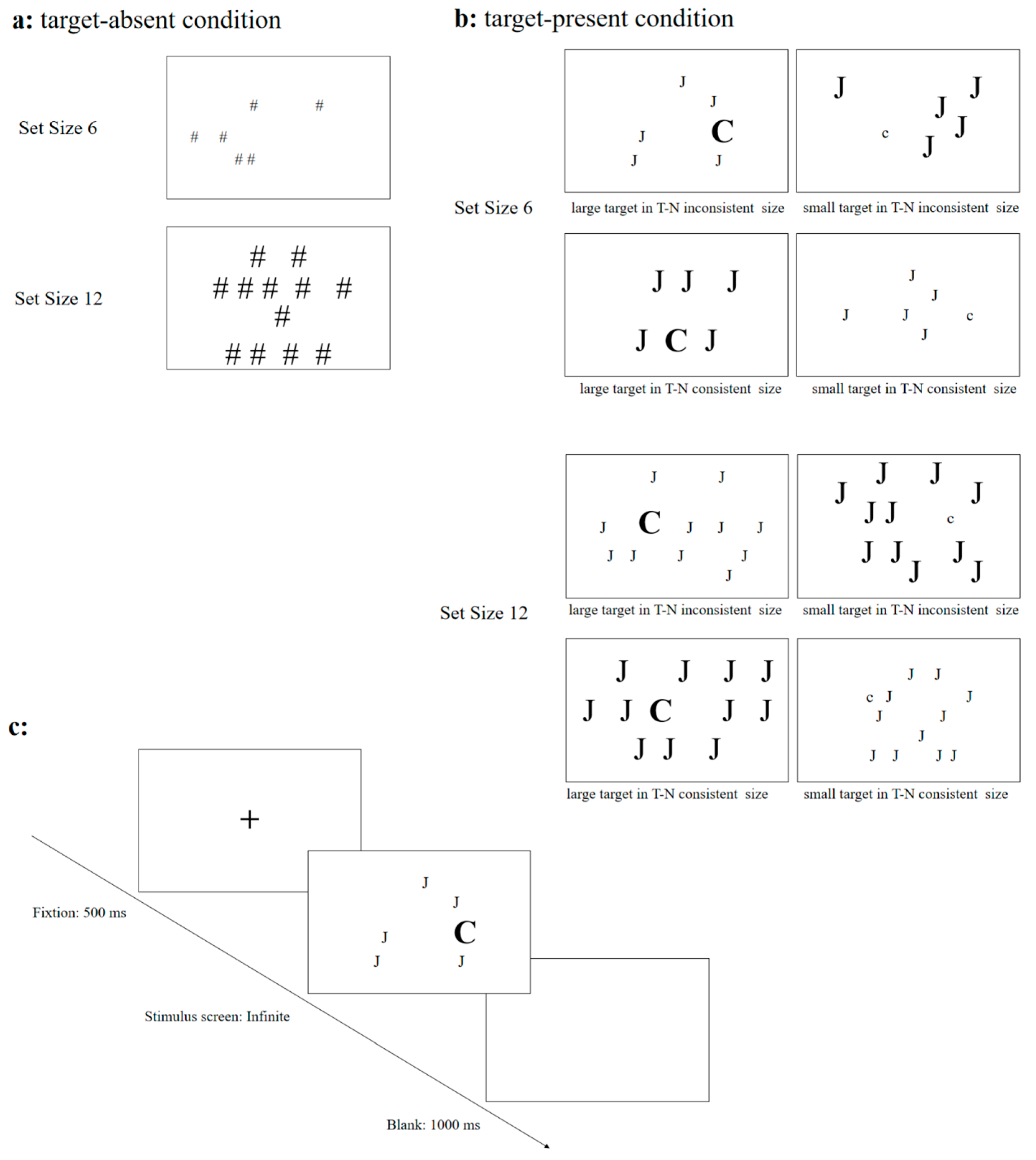

2.2. Design

2.3. Materials

2.4. Procedure

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allenmark, F., Shi, Z., Pistorius, R. L., Theisinger, A. L., Koutsouleris, N., Falkai, P., Müller, J. H., & Falter-Wagner, M. C. (2021). Acquisition and use of ‘Priors’ in autism: Typical in deciding where to look, atypical in deciding what is there. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(10), 3744–3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrita, P., Kami, K., & Kenith, S. (2014). Individuals with autism experience stronger visual capture by shape singletons than neurotypicals. Journal of Vision, 14(10), 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcangelo, U., Mauro, E., & Barbara, T. (2020). Compatibility between response position and either object typical size or semantic category: SNARC- and MARC-like effects in primary school children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 189, 104682–104699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, R., & Happé, F. (2018). Evidence of reduced global processing in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(4), 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkert, J., & Remington, A. (2020). Making sense of the perceptual capacities in autistic and non-autistic adults. Autism, 24(7), 1795–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, J., Davila, A., & Satish, A. (2017). Inter-Edge Grouping: Are many figure-ground principles actually perceptual grouping? Journal of Vision, 17(10), 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, C. O., Dixon, D. R., Novack, M., & Granpeesheh, D. (2017). A systematic review of assessments for sensory processing abnormalities in autism spectrum disorder. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 4(3), 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Cai, W., Xie, T., & Fu, S. (2020). The characteristics and neural mechanisms of visual orienting and visual search in autism spectrum disorders. Advances in Psychological Science, 28(1), 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z., Zhang, T., Hu, S., Tian, Y., Zhao, J., & Wang, Y. (2023). The influence of perceptual load on gaze-induced attentional orienting: The modulation of expectation. Consciousness and Cognition, 113, 103543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constable, P. (2010). Crowding and visual search in high functioning adults with autism spectrum disorder. Clinical Optometry, 2, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J. F., Wang, J., Fan, H. Z., Yao, J., Chen, N., Duan, J. H., & Zhou, Y. (2017). Norm development of the Chinese edition of wechsler adult intelligence scale-fourth edition. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 31(8), 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellapiazza, F., Vernhet, C., Blanc, N., Miot, S., Schmidt, R., & Baghdadli, A. (2018). Links between sensory processing, adaptive behaviours, and attention in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Psychiatry Research, 270, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, B. R., Charman, T., Johnson, M. H., Scerif, G., Gliga, T., & BASIS Team. (2018). Visual search and autism symptoms: What young children search for and co-occurring ADHD matter. Developmental Science, 21(5), e12661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dresp-Langley, B., & Reeves, A. (2020). Color for the perceptual organization of the pictorial plane: Victor Vasarely’s legacy to Gestalt psychology. Heliyon, 6(7), e04375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, D., Lymer, E., Gibson, B. E., Desarkar, P., & Nalder, E. (2017). Assessing sensory processing dysfunction in adults and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: Ascoping review. Brain Sciences, 7(8), 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J., & Humphreys, G. W. (1989). Visual search and stimulus similarity. Psychological Review, 96(3), 433–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evers, K., Hallen, R., Noens, I., & Johan, W. (2018). Perceptual organization in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Child Development Perspectives, 12(3), 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3.1: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gliga, T., Bedford, R., Charman, T., Johnson, M. H., & The BASIS Team. (2015). Enhanced visual search in infancy predicts emerging autism symptoms. Current Biology, 25, 1727–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubb, M. A., Behrmann, M., Egan, R., Minshew, N. J., Heeger, D. J., & Carrasco, M. (2013). Exogenous spatial attention: Evidence for intact functioning in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Vision, 13(14), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happe, F. (1996). Studying weak central coherence at low levels: Children with autism do not succumb to visual illusions. A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 37, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happé, F., & Booth, R. D. L. (2008). The power of the positive: Revisiting weak coherence in autism spectrum disorders. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 61, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happé, F., & Frith, U. (2006). The weak coherence account: Detail-focused cognitive style in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(1), 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horstmann, G., Becker, S. I., Bergmann, S., & Burghaus, L. (2010). A reversal of the search asymmetry favoring negative schematic faces. Visual Cognition, 18(7), 981–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, R. M., Keehn, B., Connolly, C., Wolfe, J. M., & Horowitz, T. S. (2009). Why is visual search superior in autism spectrum disorder? Developmental Science, 12(6), 1083–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldy, Z., Giserman, I., Carter, A. S., & Blaser, E. (2016). The mechanisms underlying the ASD advantage in visual search. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(5), 1513–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keehn, B., & Joseph, R. M. (2016). Slowed search in the context of unimpaired grouping in autism: Evidence from multiple conjunction search. Autism Research, 9(3), 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keehn, B., Kadlaskar, G., & McNally Keehn, R. (2023). Elevated and accelerated: Locus coerceus activity and visual search abilities in autistic children. Cortex, 169, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keehn, B., Shih, P., Brenner, L. A., Townsend, J., & Müller, R. A. (2013). Functional connectivity for an “island of sparing” in autism spectrum disorder: An fMRI study of visual search. Human Brain Mapping, 34(10), 2524–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koehler, K., Guo, F., Zhang, S., & Eckstein, M. P. (2014). What do saliency models predict. Journal of Vision, 14(3), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koldewyn, K., Jiang, Y. V., Weigelt, S., & Kanwisher, N. (2013). Global/local processing in autism: Not a disability, but a disinclination. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(10), 2329–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, N. (2005). Distracted and confused? Selective attention under load. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(2), 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, N., & Cox, S. (1997). On the efficiency of visual selective attention: Efficient visual search leads to inefficient distractor rejection. Psychological Science, 8(5), 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindor, E., Rinehart, N., & Fielding, J. (2018). Superior visual search and crowding abilities are not characteristic of all individuals on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(10), 3499–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, S. A. (2011). A Study on Visual Search Asymmetries. Science of Social Psychology, 26(9), 29–33, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Manjaly, Z. M., Bruning, N., Neufang, S., Stephan, K. E., Brieber, S., Marshall, J. C., Kamp-Becker, I., Remschmidt, H., Herpertz-Dahlmann, B., Konrad, K., & Fink, G. R. (2007). Neurophysiological correlates of relatively enhanced local visual search in autistic adolescents. NeuroImage, 35(1), 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marciano, H., Gal, E., Kimchi, R., Hedley, D., Goldfarb, Y., & Bonneh, Y. S. (2021). Visual detection and decoding skills of aerial photography by adults with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52(3), 1346–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masedu, F., Vagnetti, R., Pino, M. C., Valenti, M., & Mazza, M. (2022). Comparison of visual fixation trajectories in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder and typical development: A markov chain model. Brain Sciences, 12(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottron, L., Bouvet, L., Bonnel, A., Samson, F., Burack, J. A., Dawson, M., & Heaton, P. (2013). Veridical mapping in the development of exceptional autistic abilities. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 37, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottron, L., Dawson, M., Soulières, I., Hubert, B., & Burack, J. (2006). Enhanced perceptual functioning in autism: An update, and eight principles of autistic perception. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(1), 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, G., Groeger, J. A., & Greene, C. M. (2016). Twenty years of load theory—Where are we now, and where should we go next? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 23(5), 1316–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayar, K., Voyles, A. C., Kiorpes, L., & Di Martino, A. (2017). Global and local visual processing in autism: An objective assessment approach. Autism Research, 10(8), 1392–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neisser, U. (1963). Decision-time without reaction-time: Experiments in visual scanning. The American Journal of Psychology, 76(3), 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J. E., Falck-Ytter, T., & Bölte, S. (2018). Local and global visual processing in 3-year-olds with and without autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48, 2249–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oomen, D., Jan, R., Wiersema, G. O., & Emiel, C. (2024). Top-down biological motion perception does not differ between adults scoring high versus low on autism traits. Biological Psychology, 190, 108820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, S. E., & Beck, D. M. (2007). The repetition discrimination task: An objective method for studying perceptual grouping. Perception & Psychophysics, 69(1), 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X. L., & Huang, D. (2018). The influence of task difficulty on the emergence of visual search advantages in children with autism. Psychological Science, 41(2), 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkham, A. E., Griffin, M., Baron, R., Sasson, N. J., & Gur, R. C. (2010). The face in the crowd effect: Anger superiority when using real faces and multiple identities. Emotion, 10(1), 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaisted, K., O’Riordan, M., & Baron-Cohen, S. (1998). Enhanced visual search for a conjunctive target in autism: A research note. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 39(5), 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proulx, M. J. (2010). Size matters: Large objects capture attention in visual search. PLoS ONE, 5(12), e15293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A. F., Mihalas, S., von der Heydt, R., Niebur, E., & Etienne-Cummings, R. (2016). A model of proto-object based saliency. Vision Research, 94, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabrina, S., Letizia, P., & Emma, G. (2023). Symmetry detection in autistic adults benefits from local processing in a contour integration task. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 54, 3684–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlooz, W. A. J. M., & Hulstijn, W. (2014). Boys with autism spectrum disorders show superior performance on the adult embedded figures test. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W., Leng, Y., & Yu, Z. (2021). The roles of symbolic and numerical representations in asymmetric visual search. Acta Psychologica, 219, 103397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W., Yu, Z., & Leng, Y. (2024). The role of semantic size and stimulus quantity in asymmetric visual search. Psychological Research, 17(1), 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirama, A., Kato, N., & Kashino, M. (2017). When do individuals with autism spectrum disorder show superiority in visual search? Autism, 21(8), 942–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spek, A. A., Scholte, E. M., & Van Berckelaer-Onnes, I. A. (2010). Theory of mind in adults with HFA and Asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(3), 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshihiko, M., Shozo, T., Naoko, I., Naoya, O., Toshiaki, O., Shigenobu, K., & Yoko, K. (2011). Top-down and bottom-up visual information processing of non-social stimuli in high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treccani, B., Mulatti, C., Sulpizio, S., & Job, R. (2019). Does perceptual simulation explain spatial effects in word categorization? Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treisman, A., & Gelade, G. (1980). A feature-integration theory of attention. Cognitive Psychology, 12(1), 97–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treisman, A., & Gormican, S. (1988). Feature analysis in early vision: Evidence from search asymmetries. Psychological Review, 95(1), 15–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, Y., Kurosu, S., & Saiki, J. (2015). Intensity of visual search asymmetry depends on physical property in target-present trials and search type in target-absent trials. Journal of Vision, 15(12), 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, Y., Li, Q., & Kikuno, Y. (2023). Memorable scenes attract attention in visual search. Journal of Vision, 23(9), 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Cruys, S., Lemmens, L., Sapey-Triomphe, L. A., Chetverikov, A., Noens, I., & Wagemans, J. (2021). Structural and contextual priors affect visual search in children with and without autism. Autism Research, 14(7), 1484–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Hallen, R., Evers, K., Brewaeys, K., Van den Noortgate, W., & Wagemans, J. (2015). Global processing takes time: A meta-analysis on local-global visual processing in ASD. Psychological Bulletin, 141, 549–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Hallen, R., Manning, C., Evers, K., & Wagemans, J. (2019). Global motion perception in autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(12), 4901–4918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudeva, B. S., & Eric, H. (2017). Body dysmorphic disorder in patients with autism spectrum disorder: A reflection of increased local processing and self-focus. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(4), 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecera, S. P., & Behrmann, M. (2001). 6-Attention and unit formation: A biased competition account of object-based attention. Advances in Psychology, 130, 145–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagemans, J., Feldman, J., Gepshtein, S., Kimchi, R., Pomerantz, J. R., van der Helm, P. A., & van Leeuwen, C. (2012). A century of Gestalt psychology in visual perception: II. Conceptual and theoretical foundations. Psychological Bulletin, 138(6), 1252–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q., Li, X., Gong, X., Yin, T., Liu, Q., Yi, L., & Liu, J. (2023). Autistic children’s visual sensitivity to face movement. Development and Psychopathology, 36, 1616–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, J. M. (2021). Guided Search 6.0: An updated model of visual search. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 28(4), 1060–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, J. M., & Gancarz, G. (1997). Guided search 3.0. In Basic and clinical applications of vision science (pp. 189–192). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wühr, P., & Seegelke, C. (2018). Compatibility between physical stimulus size and left-right responses: Small is left and large is right. Journal of Cognition, 1(1), 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y., & Onyper, S. (2020). Visual search asymmetry depends on target-distractor feature similarity: Is the asymmetry simply a result of distractor rejection speed? Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 82(4), 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L. P., & Chen, Z. M. (2022). The current status and progress of visual search in children with autism spectrum disorder. Chinese Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 37(7), 977–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | ASD (n = 24) | TD (n = 25) | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 19.34 ± 2.44 | 20.36 ± 1.70 | 0.770 | 0.445 |

| Gender (Male) | 20 | 21 | −0.062 | 0.951 |

| WAIS-IV-C Score | 91.21 ± 23.33 | 100.28 ± 7.16 | 1.825 | 0.079 |

| Block Design | 102.61 ± 20.21 | 99.60 ± 10.89 | −0.634 | 0.530 |

| General Knowledge | 97.39 ± 18.82 | 100.60 ± 15.30 | 0.650 | 0.519 |

| Arithmetic | 85.00 ± 18.22 | 97.20 ± 9.80 | 2.854 | 0.007 ** |

| Coding | 88.26 ± 23.38 | 104.40 ± 13.25 | 2.908 | 0.006 ** |

| Set Size 6 | Set Size 12 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD | TD | ASD | TD | |

| Large target in T-N size-consistency | 1082 ± 67 | 844 ± 66 | 1069 ± 57 | 874 ± 56 |

| Large target in T-N size-inconsistency | 1079 ± 66 | 818 ± 65 | 1061 ± 63 | 785 ± 62 |

| Small target in T-N size-consistency | 1190 ± 60 | 972 ± 59 | 1281 ± 86 | 1064 ± 84 |

| Small target in T-N size-inconsistency | 1003 ± 56 | 817 ± 55 | 1145 ± 66 | 840 ± 64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shen, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fu, S. The Impact of Perceptual Load and Distractors’ Perceptual Grouping on Visual Search in ASD. Behav. Sci. 2026, 16, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010080

Shen W, Huang Y, Zhang L, Fu S. The Impact of Perceptual Load and Distractors’ Perceptual Grouping on Visual Search in ASD. Behavioral Sciences. 2026; 16(1):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010080

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Wenyi, Yijie Huang, Lin Zhang, and Shimin Fu. 2026. "The Impact of Perceptual Load and Distractors’ Perceptual Grouping on Visual Search in ASD" Behavioral Sciences 16, no. 1: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010080

APA StyleShen, W., Huang, Y., Zhang, L., & Fu, S. (2026). The Impact of Perceptual Load and Distractors’ Perceptual Grouping on Visual Search in ASD. Behavioral Sciences, 16(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010080