Time Trends in Peer Violence and Bullying Across Countries and Regions of Europe, Central Asia, and Canada Among Students Aged 11, 13, and 15 from 2013 to 2022

Abstract

1. Introduction

Purpose of the Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Instrument

2.2.1. Bullying Perpetration and Victimization

2.2.2. Cyberbullying Perpetration and Victimization

2.2.3. Physical Fighting

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physical Fighting

3.2. Bullying Perpetration

3.3. Bullying Victimization

3.4. Cyberbullying Perpetration

3.5. Cyberbullying Victimization

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Practice

4.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agnew, R. (1992). Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology, 30(1), 47–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, R. (2001). Building on the foundation of general strain theory: Specifying the types of strain most likely to lead to crime and delinquency. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 38(4), 319–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Cohen, P., & Chen, S. (2010). How big is a big odds ratio? Interpreting the magnitudes of odds ratios in epidemiological studies. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation, 39(4), 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44(4), 588–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, W., Boniel-Nissim, M., King, N., Walsh, S. D., Boer, M., Donnelly, P. D., Harel-Fisch, Y., Malinowska-Cieślik, M., Gaspar de Matos, M., Cosma, A., Van den Eijnden, R., Vieno, A., Elgar, F. J., Molcho, M., Bjereld, Y., & Pickett, W. (2020). Social media use and cyber-bullying: A cross-national analysis of young people in 42 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(Suppl. S6), S100–S108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, L. L. (1998). Youth violence in the United States: Major trends, risk factors, and prevention approaches. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J., Zhou, F., Hou, W., Heybati, K., Lohit, S., Abbas, U., Silver, Z., Wong, C. Y., Chang, O., Huang, E., Zuo, Q. K., Moskalyk, M., Ramaraju, H. B., & Heybati, S. (2023). Prevalence of mental health symptoms in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1520(1), 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froggio, G., Vettorato, G., & Lori, M. (2023). COVID-19 pandemic as subjective repeated strains and its effects on deviant behavior in a sample of Italian youth. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 68(16), 1717–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study. (2023). Data browser (findings from the 2021/22 international HBSC survey) [Data set]. Available online: https://data-browser.hbsc.org (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2012). A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(4), 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, L. T., Dotson, M. P., Suleiman, A. B., Burke, N. L., Johnson, J. B., & Cohen, A. K. (2023). Internalizing the COVID-19 pandemic: Gendered differences in youth mental health. Current Opinion in Psychology, 52, 101636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N., Zhang, S., Mu, Y., Yu, Y., Riem, M. M. E., & Guo, J. (2024). Does the COVID-19 pandemic increase or decrease the global cyberbullying behaviors? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 25(2), 1018–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, D., Popovich, D. L., Moon, S., & Román, S. (2023). How to calculate, use, and report variance explained effect size indices and not die trying. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 33(1), 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchley, J., Currie, D., Samdal, O., Jåstad, A., Cosma, A., & Nic Gabhainn, S. (Eds.). (2023). Health behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study protocol: Background, methodology and mandatory items for the 2021/22 survey. MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow. [Google Scholar]

- Kassambara, A. (2023). rstatix: Pipe-friendly framework for basic statistical tests (R package version 0.7.2). Available online: https://rpkgs.datanovia.com/rstatix/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Kasturiratna, K. T. A. S., Hartanto, A., Chen, C. H. Y., Tong, E. M. W., & Majeed, N. M. (2025). Umbrella review of meta-analyses on the risk factors, protective factors, consequences and interventions of cyberbullying victimization. Nature Human Behaviour, 9(1), 101–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R. S. (2019). Bullying Trends in the United States: A Meta-Regression. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(4), 914–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R. S., & Dendy, K. (2024). Traditional bullying and cyberbullying victimization before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Bullying Prevention. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, R. J. R. (2011). Externalizing and internalizing symptoms. In R. J. R. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 903–905). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, S., Racine, N., Vaillancourt, T., Korczak, D. J., Hewitt, J. M. A., Pador, P., Park, J. L., McArthur, B. A., Holy, C., & Neville, R. D. (2023). Changes in depression and anxiety among children and adolescents from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 177(6), 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. (1997). Bully/victim problems in school: Facts and intervention. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 12(4), 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, U., Salazar de Pablo, G., Franco, M., Moreno, C., Parellada, M., Arango, C., & Fusar-Poli, P. (2023). The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: Systematic review. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 32(7), 1151–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patte, K. A., Gohari, M. R., Lucibello, K. M., Bélanger, R. E., Farrell, A. H., & Leatherdale, S. T. (2024). A prospective and repeat cross-sectional study of bullying victimization among adolescents from before COVID-19 to the two school years following the pandemic onset. Journal of School Violence, 23(4), 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G., Albanesi, C., & Cicognani, E. (2018). The relationship between sense of community in the school and students’ aggressive behavior: A multilevel analysis. School Psychology Quarterly, 33, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G., & Ghinassi, S. (2025). Crime trends among Italian minors: Observed changes during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Crime Science, 14(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G., & Mancini, A. D. (2021). The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns: A review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychological Medicine, 51(2), 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G., & Tomasetto, C. (2022). Early pubertal development and deviant behavior: A three-year longitudinal study among early adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 193, 111621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regalado, J., Timmer, A., & Jawaid, A. (2022). Crime and deviance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sociology Compass, 16(4), e12974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repo, J., Herkama, S., & Salmivalli, C. (2023). Bullying interrupted: Victimized students in remote schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 5(3), 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signorell, A. (2025). DescTools: Tools for descriptive statistics (R package version 0.99.59). Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=DescTools (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Sorrentino, A., Sulla, F., Santamato, M., di Furia, M., Toto, G. A., & Monacis, L. (2023). Has the COVID-19 pandemic affected cyberbullying and cybervictimization prevalence among children and adolescents? A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(10), 5825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanrikulu, I. (2017). Cyberbullying prevention and intervention programs in schools: A systematic review. School Psychology International, 39(1), 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczak, M., & Tomczak, E. (2014). The need to report effect size estimates revisited. An overview of some recommended measures of effect size. Trends in Sport Sciences, 21(1), 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt, T., Brittain, H., Krygsman, A., Farrell, A. H., Landon, S., & Pepler, D. (2021). School bullying before and during COVID-19: Results from a population-based randomized design. Aggressive Behavior, 47(5), 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillancourt, T., Farrell, A. H., Brittain, H., Krygsman, A., Vitoroulis, I., & Pepler, D. (2023). Bullying before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Opinion in Psychology, 53, 101689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, S. D., Elgar, F., Craig, W., Cosma, A., Donnelly, P. D., Harel-Fisch, Y., Molcho, M., Malinowska-Cieslik, M., Ng, K., & Pickett, W. (2025). COVID-19 school closures and peer violence in adolescents in 42 countries: Evidence from the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Study. International Journal of Bullying Prevention. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

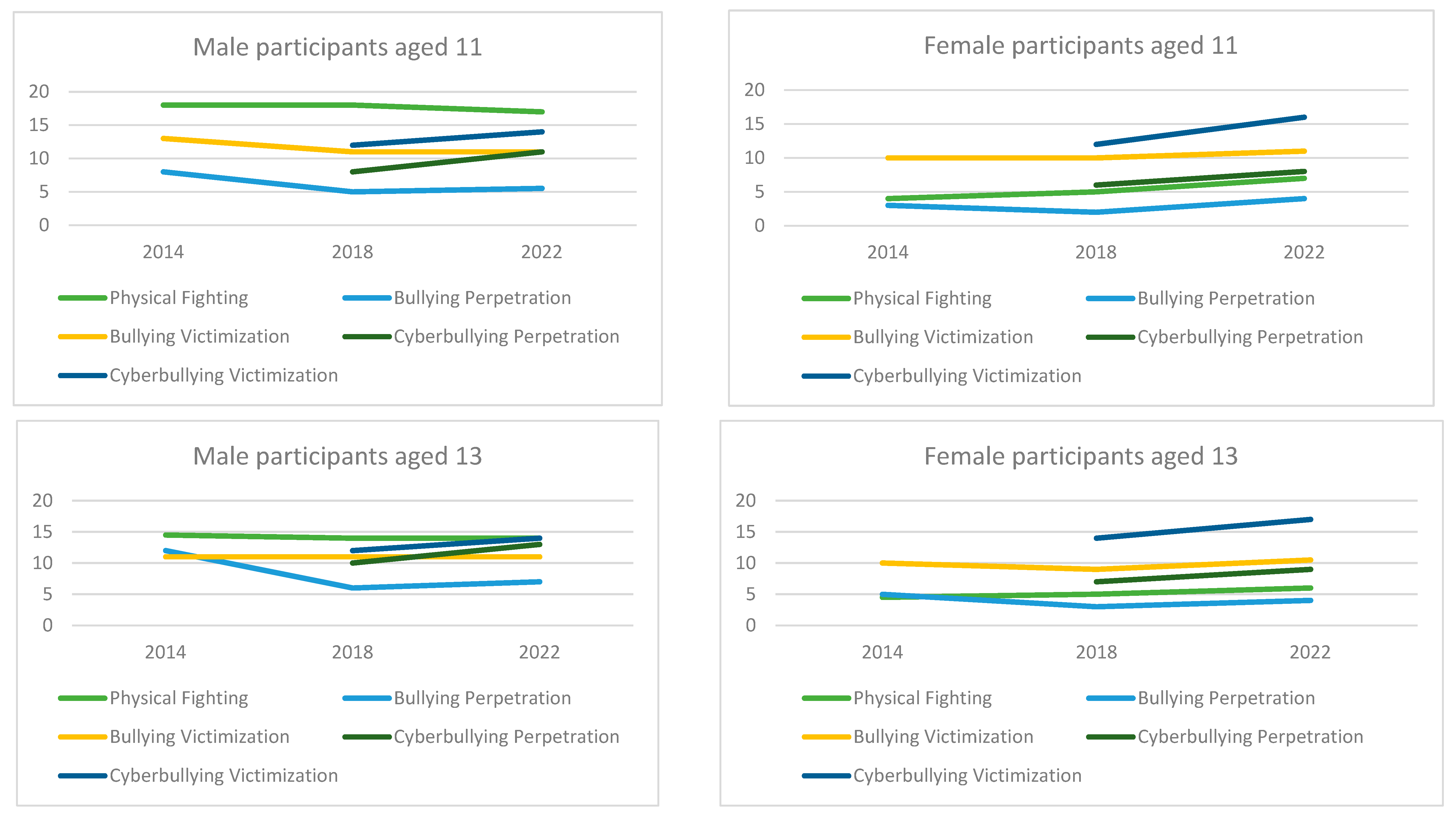

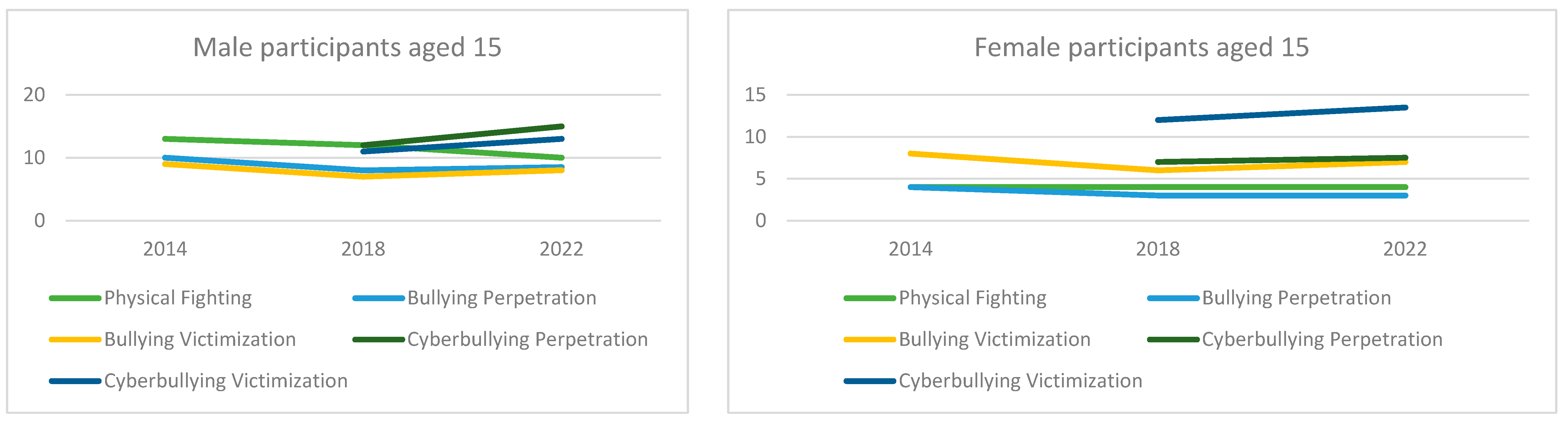

| Age | Year | Gender | Physical Fighting | Bullying Perpetration | Bullying Victimization | Cyberbullying Perpetration | Cyberbullying Victimization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mdn | IQR | Mdn | IQR | Mdn | IQR | Mdn | IQR | Mdn | IQR | |||

| 11 | 2014 | Male | 18.0 | 5.3 | 8.0 | 9.5 | 13.0 | 7.5 | — | — | — | — |

| 11 | 2018 | Male | 18.0 | 5.8 | 5.0 | 9.0 | 11.0 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 9.0 | 12.0 | 7.0 |

| 11 | 2022 | Male | 17.0 | 6.0 | 5.5 | 7.3 | 11.0 | 6.3 | 11.0 | 8.3 | 14.0 | 6.3 |

| 13 | 2014 | Male | 14.5 | 6.5 | 12.0 | 9.0 | 11.0 | 7.0 | — | — | — | — |

| 13 | 2018 | Male | 14.0 | 4.8 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 11.0 | 7.0 | 10.0 | 7.0 | 12.0 | 8.0 |

| 13 | 2022 | Male | 14.0 | 5.0 | 7.0 | 6.3 | 11.0 | 6.0 | 13.0 | 6.3 | 14.0 | 5.5 |

| 15 | 2014 | Male | 13.0 | 4.0 | 10.0 | 9.5 | 9.0 | 5.5 | — | — | — | — |

| 15 | 2018 | Male | 12.0 | 3.8 | 8.0 | 5.0 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 12.0 | 8.0 | 11.0 | 7.0 |

| 15 | 2022 | Male | 10.0 | 4.0 | 8.5 | 5.0 | 8.0 | 6.0 | 15.0 | 5.8 | 13.0 | 5.5 |

| 11 | 2014 | Female | 4.0 | 1.3 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 6.0 | — | — | — | — |

| 11 | 2018 | Female | 5.0 | 3.8 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 10.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 12.0 | 7.0 |

| 11 | 2022 | Female | 7.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 11.0 | 5.0 | 8.0 | 5.0 | 16.0 | 7.0 |

| 13 | 2014 | Female | 4.5 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 7.5 | 10.0 | 6.0 | — | — | — | — |

| 13 | 2018 | Female | 5.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 9.0 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 14.0 | 9.0 |

| 13 | 2022 | Female | 6.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 10.5 | 6.3 | 9.0 | 5.0 | 17.0 | 8.3 |

| 15 | 2014 | Female | 4.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 8.0 | 4.0 | — | — | — | — |

| 15 | 2018 | Female | 4.0 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 3.0 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 12.0 | 7.0 |

| 15 | 2022 | Female | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 7.5 | 3.3 | 13.5 | 5.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Prati, G. Time Trends in Peer Violence and Bullying Across Countries and Regions of Europe, Central Asia, and Canada Among Students Aged 11, 13, and 15 from 2013 to 2022. Behav. Sci. 2026, 16, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010036

Prati G. Time Trends in Peer Violence and Bullying Across Countries and Regions of Europe, Central Asia, and Canada Among Students Aged 11, 13, and 15 from 2013 to 2022. Behavioral Sciences. 2026; 16(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010036

Chicago/Turabian StylePrati, Gabriele. 2026. "Time Trends in Peer Violence and Bullying Across Countries and Regions of Europe, Central Asia, and Canada Among Students Aged 11, 13, and 15 from 2013 to 2022" Behavioral Sciences 16, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010036

APA StylePrati, G. (2026). Time Trends in Peer Violence and Bullying Across Countries and Regions of Europe, Central Asia, and Canada Among Students Aged 11, 13, and 15 from 2013 to 2022. Behavioral Sciences, 16(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010036