Preschoolers’ Win–Stay/Lose–Shift Strategy Use in the Children’s Gambling Task

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Children’s Gambling Task

1.2. Win–Stay and Lose–Shift as a Decision-Making Strategy

1.3. Individual Differences in Cognitive Self-Regulation: Executive Function and Metacognition

1.4. Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

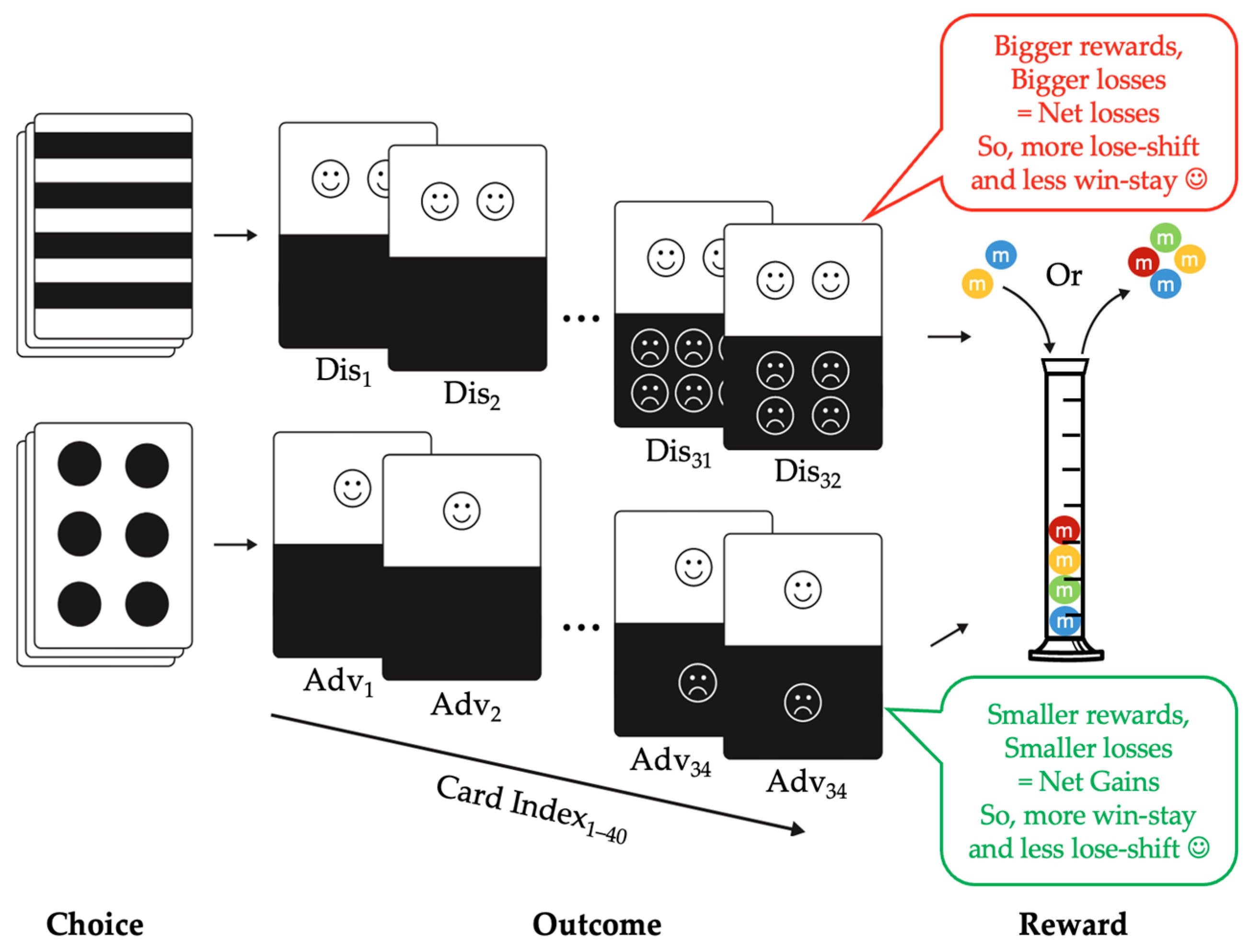

2.3.1. Children’s Gambling Task (CGT)

2.3.2. Metacognition Interview

2.3.3. Minnesota Executive Function Scale (MEFS)

2.3.4. Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scales for Early Childhood (5th)

2.3.5. Family Information Questionnaire

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

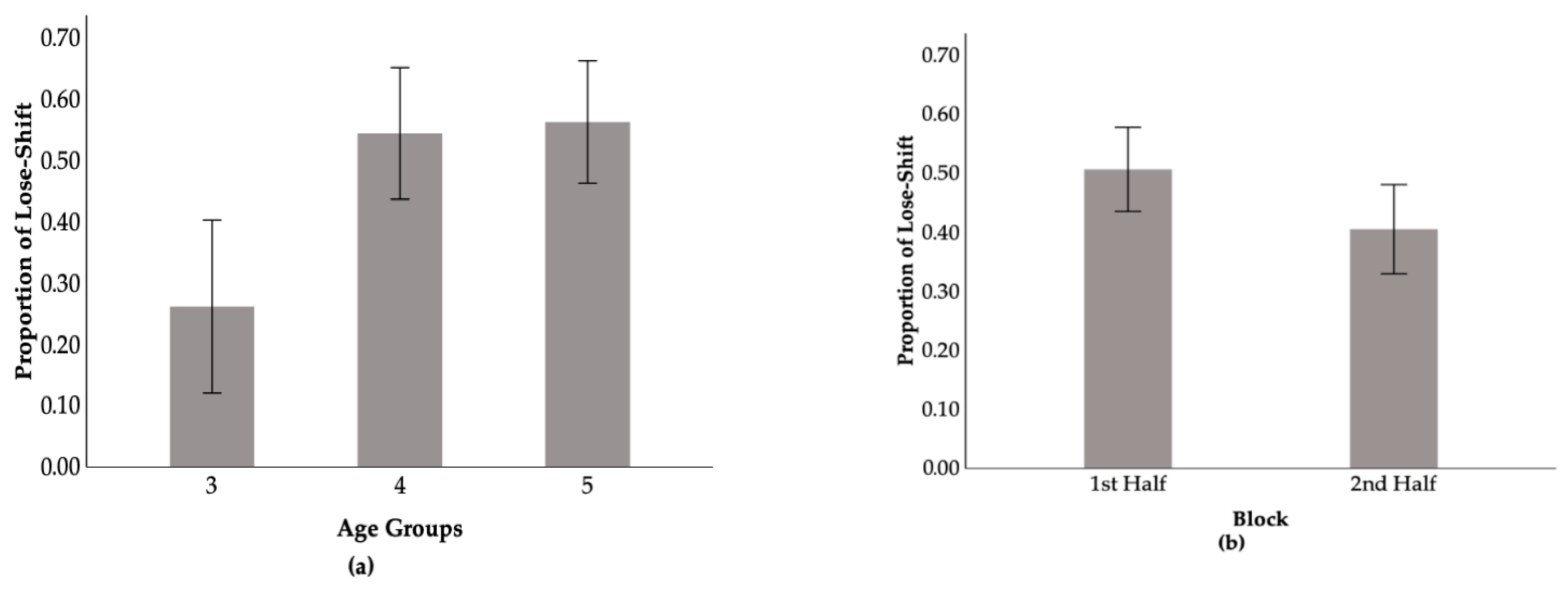

3.2. Deck-Specific Strategy Use Across Time

3.3. Relations Between Effective Deck-Specific Strategy Use and Cognitive Self-Regulation

4. Discussion

4.1. Increasing Win–Stay Behaviors for Rewarding Options

4.2. Developmental Patterns in Lose–Shift Behaviors

4.3. Metacognition Predicts Strategic Learning

4.4. Strengths, Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CGT | Children’s Gambling Task |

| EF | Executive Function |

| IGT | Iowa Gambling Task |

| MEFS | Minnesota Executive Function Scale |

| PGT | Preschool Gambling Task |

| SES | Socioeconomic Status |

Appendix A

| No. | Dis | Adv | No. | Dis | Adv | No. | Dis | Adv | No. | Dis | Adv |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 31 | −6 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 12 | −6 | −1 | 22 | −6 | 0 | 32 | −4 | 0 |

| 3 | −4 | −1 | 13 | 0 | −1 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 33 | −5 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 14 | −5 | 0 | 24 | −6 | −1 | 34 | 0 | −1 |

| 5 | −6 | −1 | 15 | −4 | 0 | 25 | 0 | −1 | 35 | 0 | −1 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 26 | −4 | −1 | 36 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | −4 | −1 | 17 | −6 | −1 | 27 | −5 | 0 | 37 | −4 | −1 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 18 | −4 | −1 | 28 | −4 | 0 | 38 | −6 | 0 |

| 9 | −5 | −1 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 0 | −1 | 39 | 0 | −1 |

| 10 | −6 | −1 | 20 | 0 | −1 | 30 | 0 | −1 | 40 | 0 | −1 |

|

References

- Aïte, A., Cassotti, M., Rossi, S., Poirel, N., Lubin, A., Houdé, O., & Moutier, S. (2012). Is human decision making under ambiguity guided by loss frequency regardless of the costs? A developmental study using the soochow gambling task. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 113(2), 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, G., & Moussaumai, J. (2015). Improving children’s affective decision making in the children’s gambling task. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 139, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechara, A., Damasio, A. R., Damasio, H., & Anderson, S. (1994). Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to human prefrontal cortex. Cognition, 50, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (1997). Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science, 275(5304), 1293–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boseovski, J. J. (2010). Evidence for “Rose-colored glasses”: An examination of the positivity bias in young children’s personality judgments. Child Development Perspectives, 4(3), 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslav, A. D. S., Zucker, N. L., Schechter, J. C., Majors, A., Bidopia, T., Fuemmeler, B. F., Kollins, S. H., & Huettel, S. A. (2022). Shuffle the decks: Children are sensitive to incidental nonrandom structure in a sequential-choice task. Psychological Science, 33(4), 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunch, K. M., & Andrews, G. (2012). Development of relational processing in hot and cool tasks. Developmental Neuropsychology, 37(2), 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunch, K. M., Andrews, G., & Halford, G. S. (2007). Complexity effects on the children’s gambling task. Cognitive Development, 22(3), 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, S. M. (2005). Developmentally sensitive measures of executive function in preschool children. Developmental Neuropsychology, 28(2), 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, S. M., & Zelazo, P. D. (2014). Minnesota executive function scale: Test manual. Reflection Sciences, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, B. J., Somerville, L. H., Gotlib, I. H., Ayduk, O., Franklin, N. T., Askren, M. K., Jonides, J., Berman, M. G., Wilson, N. L., Teslovich, T., Glover, G., Zayas, V., Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (2011). Behavioral and neural correlates of delay of gratification 40 years later. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(36), 14998–15003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassotti, M., Houdé, O., & Moutier, S. (2011). Developmental changes of win-stay and loss-shift strategies in decision making. Child Neuropsychology, 17(4), 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crone, E. A., & van der Molen, M. W. (2004). Developmental changes in real life decision making: Performance on a gambling task previously shown to depend on the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Developmental Neuropsychology, 25(3), 251–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daw, N. D., O’Doherty, J. P., Dayan, P., Seymour, B., & Dolan, R. J. (2006). Cortical substrates for exploratory decisions in humans. Nature, 441(7095), 876–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defoe, I. N., Dubas, J. S., Figner, B., & van Aken, M. A. G. (2015). A meta-analysis on age differences in risky decision making: Adolescents versus children and adults. Psychological Bulletin, 141(1), 48–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, H., Aldecosea, C., Menéndez, Ñ., Rodríguez, R., Nin, V., Lipina, S., & Carboni, A. (2022). Socioeconomic status differences in children’s affective decision-making: The role of awareness in the children’s gambling task. Developmental Psychology, 58(9), 1716–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forder, L., & Dyson, B. J. (2016). Behavioural and neural modulation of win-stay but not lose-shift strategies as a function of outcome value in rock, paper, scissors. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 33809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S., Wei, Y., Bai, J., Lin, C., & Li, H. (2009). Young children’s affective decision-making in a gambling task: Does difficulty in learning the gain/loss schedule matter? Cognitive Development, 24(2), 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garon, N. (2016). A review of hot executive functions in preschoolers. Journal of Self-Regulation and Regulation, 2, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garon, N., & Doucet, E. (2024). To explore or exploit: Individual differences in preschool decision making. Cognitive Development, 70, 101432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garon, N., & English, S. D. (2022). Heterogeneity of decision-making strategies for preschoolers on a variant of the IGT. Applied Neuropsychology: Child, 11(4), 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garon, N., Hecker, O., Kwan, A., Crocker, T. A., & English, S. D. (2023). Integrated versus trial specific focus improves decision-making in older preschoolers. Child Neuropsychology, 29(1), 28–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garon, N., & Moore, C. (2004). Complex decision-making in early childhood. Brain and Cognition, 55(1), 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garon, N., & Moore, C. (2007). Developmental and gender differences in future-oriented decision-making during the preschool period. Child Neuropsychology, 13(1), 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopnik, A. (2020). Childhood as a solution to explore–exploit tensions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 375(1803), 20190502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happaney, K., & Zelazo, P. D. (2004). Resistance to extinction: A measure of orbitofrontal function suitable for children? Brain and Cognition, 55(1), 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilman, R. M., Miu, A. C., & Benga, O. (2008). Developmental and sex-related differences in preschoolers’ affective decision making. Child Neuropsychology, 15(1), 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hongwanishkul, D., Happaney, K. R., Lee, W. S. C., & Zelazo, P. D. (2005). Assessment of hot and cool executive function in young children: Age-related changes and individual differences. Developmental Neuropsychology, 28(2), 617–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivan, V. E., Banks, P. J., Goodfellow, K., & Gruber, A. J. (2018). Lose-shift responding in humans is promoted by increased cognitive load. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, A., & Zelazo, P. D. (2004). Development of “hot” executive function: The children’s gambling task. Brain and Cognition, 55(1), 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, C., Palmeri, H., & Aslin, R. N. (2013). Rational snacking: Young children’s decision-making on the marshmallow task is moderated by beliefs about environmental reliability. Cognition, 126(1), 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S., Berry, D., & Carlson, S. M. (2025). Should I stay or should I go? Children’s persistence in the context of diminishing rewards. Developmental Science, 28(1), e13585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., & Carlson, S. M. (2024). Understanding explore-exploit dynamics in child development: Current insights and future directions. Frontiers in Developmental Psychology, 2, 1467880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouklari, E.-C., Thompson, T., Monks, C. P., & Tsermentseli, S. (2017). Hot and cool executive function and its relation to theory of mind in children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Cognition and Development, 18(4), 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, F., Sallum, I., de Moraes, P. H. P., Miranda, D. M., & Malloy-Diniz, L. F. (2013a). Development of a computerised version of the children’s gambling task for the evaluation of affective decision-making in Brazilian preschool children. Estudos de Psicologia (Natal), 18(1), 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, F., Sallum, I., Miranda, D. M., Bechara, A., & Malloy-Diniz, L. F. (2013b). Do general intellectual functioning and socioeconomic status account for performance on the children’s gambling task? Frontiers in Neuroscience, 7(7), 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischel, W. (1974). Processes in delay of gratification. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 7, pp. 249–292). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “Frontal Lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41(1), 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, T. O. (1990). Metamemory: A theoretical framework and new findings. In Psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 26, pp. 125–173). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, J. P., Patterson, C. M., & Kosson, D. S. (1987). Response perseveration in psychopaths. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 96(2), 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussenbaum, K., & Hartley, C. A. (2019). Reinforcement learning across development: What insights can we draw from a decade of research? Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 40, 100733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overman, W. H. (2004). Sex differences in early childhood, adolescence, and adulthood on cognitive tasks that rely on orbital prefrontal cortex. Brain and Cognition, 55(1), 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, M. P., Hozack, N., Zauscher, B. E., McDowell, J. E., Frank, L. D., Brown, G. M., & Braff, D. L. (2001). Prefrontal, parietal, and temporal cortex networks underlie decision-making in the presence of uncertainty. NeuroImage, 13(1), 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland, S. E., Monks, C. P., & Tsermentseli, S. (2016). Cool and hot executive function as predictors of aggression in early childhood: Differentiating between the function and form of aggression. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 34(2), 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prencipe, A., & Zelazo, P. D. (2005). Development of affective decision making for self and other: Evidence for the integration of first- and third-person perspectives. Psychological Science, 16(7), 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roebers, C. M. (2017). Executive function and metacognition: Towards a unifying framework of cognitive self-regulation. Developmental Review, 45, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roid, G. H. (2003). Stanford-Binet intelligence scales for early childhood (5th ed.). Riverside Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, R. S., & Barto, A. (2018). Reinforcement learning: An introduction (2nd ed.). The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C., Barresi, J., & Moore, C. (1997). The development of future-oriented prudence and altruism in preschoolers. Cognitive Development, 12(2), 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toplak, M. E., Sorge, G. B., Benoit, A., West, R. F., & Stanovich, K. E. (2010). Decision-making and cognitive abilities: A review of associations between Iowa Gambling Task performance, executive functions, and intelligence. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(5), 562–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, T. W., Duncan, G. J., & Quan, H. (2018). Revisiting the marshmallow test: A conceptual replication investigating links between early delay of gratification and later outcomes. Psychological Science, 29(7), 1159–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wurm, F., Walentowska, W., Ernst, B., Severo, M. C., Pourtois, G., & Steinhauser, M. (2022). Task learnability modulates surprise but not valence processing for reinforcement learning in probabilistic choice tasks. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 34(1), 34–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P. D., & Carlson, S. M. (2012). Hot and cool executive function in childhood and adolescence: Development and plasticity. Child Development Perspectives, 6(4), 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age | Verbal IQ | MEFS | Metacognition | Total M&Ms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal IQ | 0.61 ** | – | |||

| MEFS | −0.08 | 0.20 | – | ||

| Metacognition | 0.25 * | 0.16 | 0.17 | – | |

| Total M&Ms | 0.12 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.48 ** | – |

| Range | 36–71 | 0–28 | 90–119 | 0–4 | −21–24 |

| M | 55.47 | 19.44 | 102.59 | 1.60 | 0.49 |

| SD | 9.45 | 4.56 | 5.95 | 1.52 | 10.95 |

| Age Groups | Block | Win–Stay | Lose–Shift | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adv M (SD) | Dis M (SD) | Adv M (SD) | Dis M (SD) | ||

| All | 1st | 0.41(0.34) | 0.46 (0.38) | 0.53 (0.39) | 0.57 (0.39) |

| 2nd | 0.55 (0.40) | 0.36 (0.41) | 0.41 (0.39) | 0.46 (0.40) | |

| 3 | 1st | 0.29 (0.41) | 0.54 (0.45) | 0.29 (0.43) | 0.26 (0.36) |

| 2nd | 0.50 (0.46) | 0.52 (0.49) | 0.23 (0.38) | 0.26 (0.37) | |

| 4 | 1st | 0.43 (0.34) | 0.49 (0.39) | 0.57 (0.38) | 0.63 (0.37) |

| 2nd | 0.59 (0.38) | 0.32 (0.36) | 0.49 (0.39) | 0.49 (0.37) | |

| 5 | 1st | 0.45 (0.31) | 0.40 (0.32) | 0.61 (0.36) | 0.68 (0.34) |

| 2nd | 0.53 (0.40) | 0.31 (0.40) | 0.44 (0.37) | 0.52 (0.41) | |

| Predictors | Advantageous Deck Win–Stay | Disadvantageous Deck Lose–Shift | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | t | p | R2 | R2 | B (SE) | t | P | R2 | R2 | |||

| Block 1 | 0.01 | – | 0.17 ** | – | ||||||||

| Age | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.07 | 0.46 | 0.648 | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.48 | 3.23 | 0.002 | ||||

| Verbal IQ | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.08 | −0.51 | 0.613 | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.15 | −0.98 | 0.331 | ||||

| Block 2 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 0.20 ** | ||||||||

| Age | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.12 | 0.73 | 0.468 | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.38 | 2.85 | 0.006 | ||||

| Verbal IQ | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.11 | −0.66 | 0.511 | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.16 | −1.24 | 0.218 | ||||

| Opp Deck | 0.18 (0.13) | 0.18 | 1.41 | 0.165 | 0.46 (0.11) | 0.46 | 4.29 | <0.001 | ||||

| Block 3 | 0.20 | 0.16 ** | 0.47 | 0.11 ** | ||||||||

| Age | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.981 | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.29 | 2.22 | 0.030 | ||||

| Verbal IQ | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.09 | −0.57 | 0.569 | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.17 | −1.37 | 0.178 | ||||

| Opp Deck | 0.22 (0.12) | 0.23 | 1.90 | 0.062 | 0.50 (0.10) | 0.50 | 4.97 | <0.001 | ||||

| MEFS | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.07 | −0.56 | 0.579 | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.873 | ||||

| Metacognition | 0.10 (0.03) | 0.43 | 3.41 | 0.001 | 0.08 (0.02) | 0.34 | 3.33 | 0.002 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, S.; Carlson, S.M. Preschoolers’ Win–Stay/Lose–Shift Strategy Use in the Children’s Gambling Task. Behav. Sci. 2026, 16, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010023

Kim S, Carlson SM. Preschoolers’ Win–Stay/Lose–Shift Strategy Use in the Children’s Gambling Task. Behavioral Sciences. 2026; 16(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Seokyung, and Stephanie M. Carlson. 2026. "Preschoolers’ Win–Stay/Lose–Shift Strategy Use in the Children’s Gambling Task" Behavioral Sciences 16, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010023

APA StyleKim, S., & Carlson, S. M. (2026). Preschoolers’ Win–Stay/Lose–Shift Strategy Use in the Children’s Gambling Task. Behavioral Sciences, 16(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010023