Coaching Bilingual Speech-Language Student Clinicians and Spanish-Speaking Caregivers to Use Culturally Adapted NDBI Techniques with Autistic Preschoolers

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Does a culturally adapted cascading coaching model lead to an increase in bilingual student clinician and Spanish-speaking caregivers’ use of NDBI techniques?

- What are caregiver and student clinician’s perspectives regarding the effectiveness of the program and areas for improvement?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Screening Assessments

2.2. Researchers

2.3. Setting, Materials, and Cultural Adaptations

2.4. Research Design

2.5. Dependent Variables

2.6. Data Collection

2.6.1. Coding of Dependent Variables and Interobserver Agreement (IOA)

2.6.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

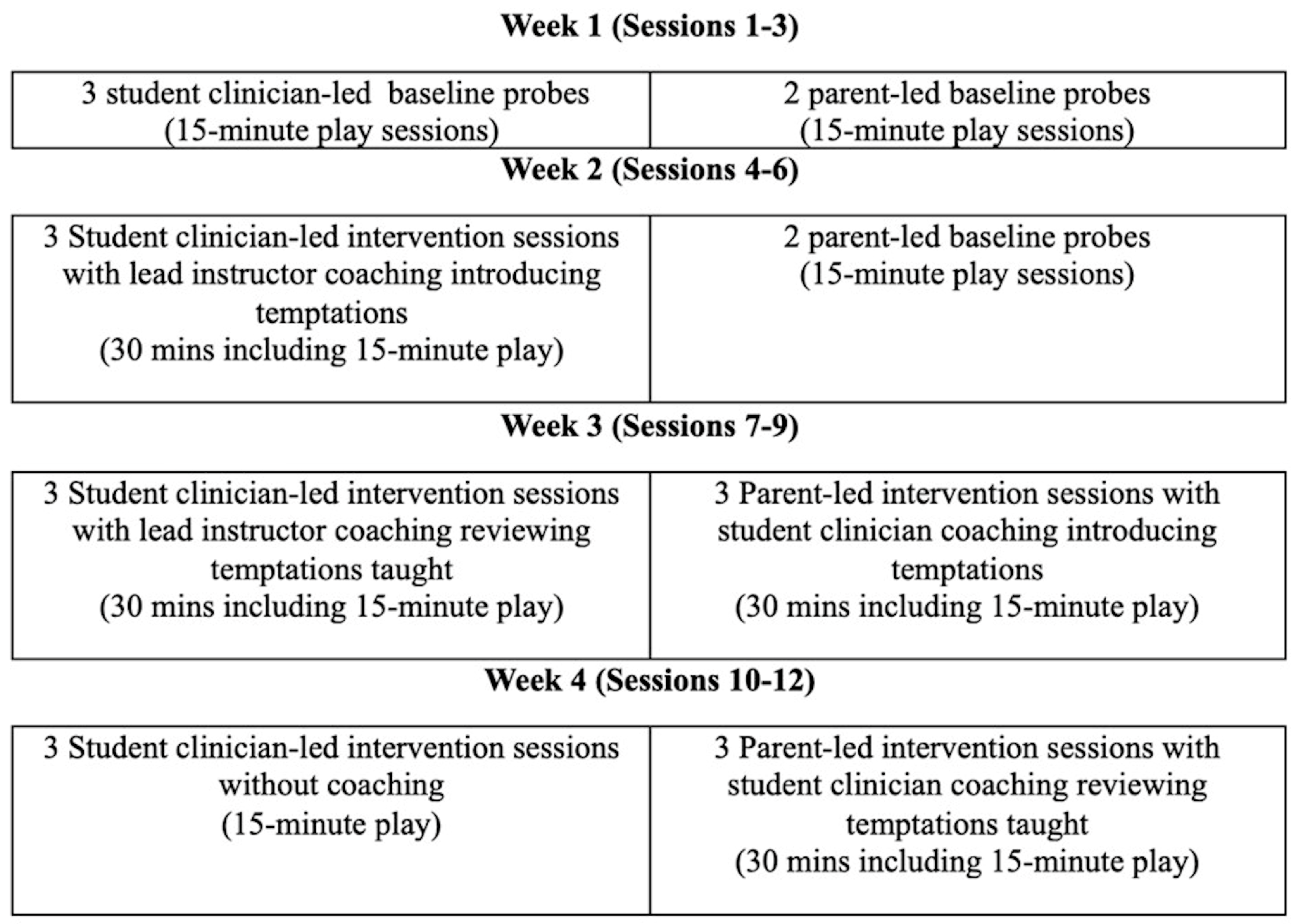

2.7. Procedures for Multiple Probe Design

2.7.1. Baseline and Target Selection

2.7.2. Group Instruction and Coaching of Students

2.7.3. Student Group Instruction in Coaching and Student-Led Caregiver Coaching

2.8. Treatment Fidelity

2.9. Data Analysis

2.9.1. Experimental Design Analysis

2.9.2. Social Validity Interview Analysis

3. Results

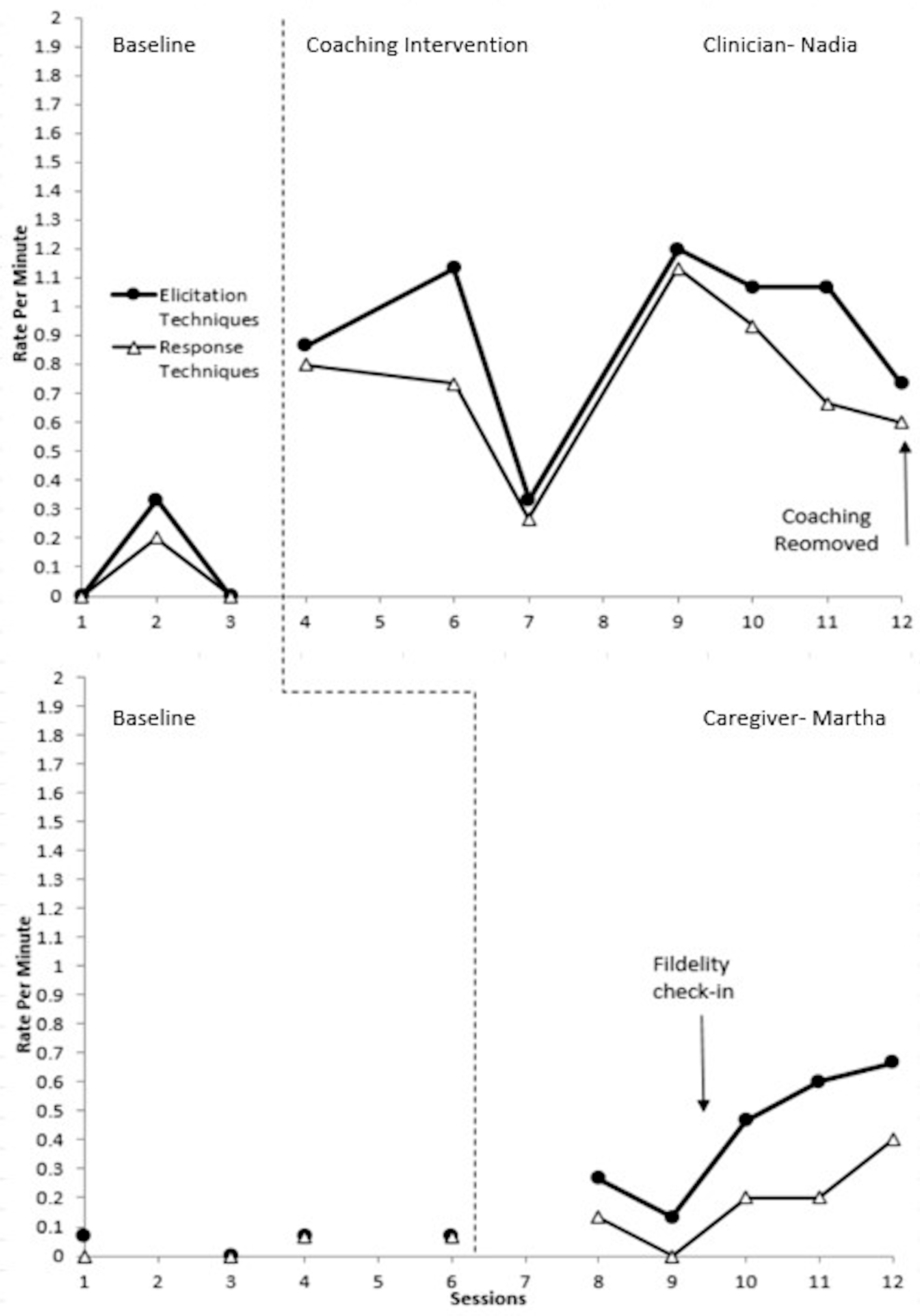

3.1. Triad 1 Experimental Results

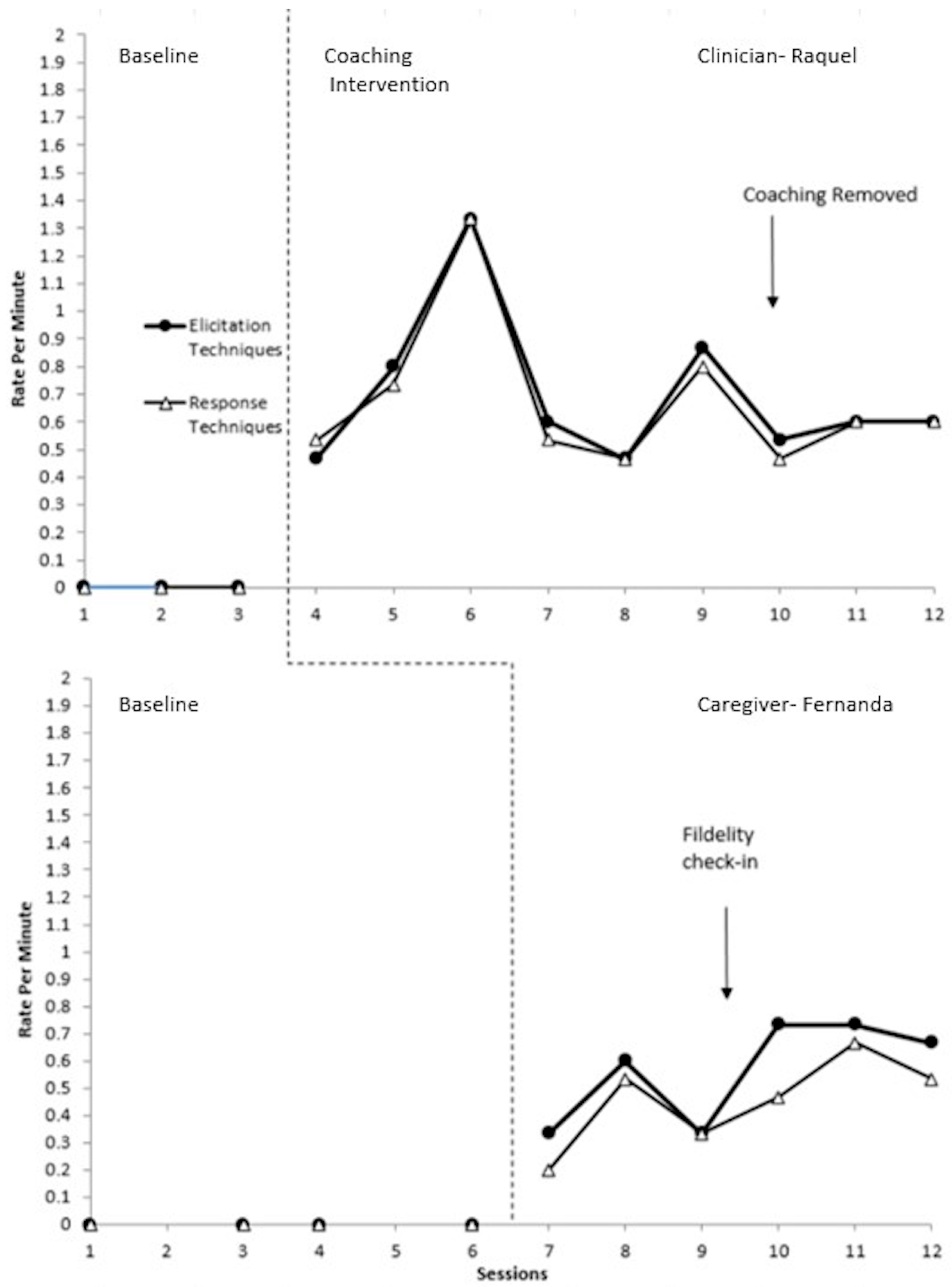

3.2. Triad 2 Experimental Results

3.3. Social Validity Results

3.3.1. Area for Improvement-Learning

3.3.2. Area for Improvement-Perspectives

3.3.3. Effectiveness-Learning

3.3.4. Effectiveness-Perspectives

3.3.5. Effectiveness-Behaviors

3.3.6. Effectiveness-Relationships

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The authors are intentionally switching between identity first language and person first language to acknowledge the diverse perspectives on language preferences. |

| 2 | While the terms Hispanic, Latino, and Latina are used in this work to reflect the self-identification of the adult participants, the author acknowledges the evolving and complex nature of racial, ethnic, and cultural terminology, and recognizes that alternative terms such as Latinx, Latine, and Latin@ are also used in various contexts. |

References

- Acosta, M., Kravzov, S., Costa, A., & Sanabria, A. (2024, December 6). Empowering Spanish-speaking SLP students: The impact and potential of Habla con Confianza [Conference presentation]. American Speech-Language Hearing Association, Seattle, WA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2025). 2024 demographic profile of ASHA members providing multilingual services. Available online: https://www.asha.org/siteassets/surveys/2024-profile-of-multilingual-service-providers.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Amsbary, J., & AFIRM Team. (2025a). Autism Focused Intervention Resources and Modules: Naturalistic intervention. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute. Available online: https://afirm-modules.fpg.unc.edu/Naturalistic-Intervention/content/ (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Amsbary, J., & AFIRM Team. (2025b). Autism Focused Intervention Resources and Modules: Parent-implemented intervention. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute. Available online: https://afirm-modules.fpg.unc.edu/Parent-Implemented%20Intervention/content/ (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2025). BACB certificant data. Available online: https://www.bacb.com/BACB-certificant-data/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Bernal, G., Bonilla, J., & Bellido, C. (1995). Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: Issues for the cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 23(1), 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brossart, D. F., Vannest, K. J., Davis, J. L., & Patience, M. A. (2014). Incorporating nonoverlap indices with visual analysis for quantifying intervention effectiveness in single-case experimental designs. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 24(3–4), 464–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruinsma, Y., Minjarez, M., Schreibman, L., & Stahmer, A. C. (2020). Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions for autism spectrum disorder. Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Buzhardt, J., Rusinko, L., Heitzman-Powell, L., Trevino-Maack, S., & McGrath, A. (2016). Exploratory evaluation and initial adaptation of a parent training program for Hispanic families of children with autism. Family Process, 55(1), 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coogle, C. G., Rahn, N. L., & Ottley, J. R. (2015). Pre-service teacher use of communication strategies upon receiving immediate feedback. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 32, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cycyk, L. M., Moore, H. W., De Anda, S., Huerta, L., Méndez, S., Patton, C., & Bourret, C. (2020). Adaptation of a caregiver-implemented naturalistic communication intervention for Spanish-speaking families of Mexican immigrant descent: A promising start. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 29(3), 1260–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiCicco, B. B., & Crabtree, B. F. (2006). The qualitative research interview. Medical Education, 40(4), 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, S. N., Dada, S., Tönsing, K., Samuels, A., & Owusu, P. (2024). Cultural considerations in caregiver-implemented naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: A scoping review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBay, M. (2022). Cultural adaptations to parent-mediated autism spectrum disorder interventions for Latin American families: A scoping review. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 31(3), 1517–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBay, M., Watson, L. R., & Zhang, W. (2018). In search of culturally appropriate autism interventions: Perspectives of Latino caregivers. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(5), 1623–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J. L., Cihon, J. H., Leaf, J. B., Van Meter, S. M., McEachin, J., & Leaf, R. (2018). Assessment of social validity trends in the journal of applied behavior analysis. European Journal of Behavior Analysis, 20(1), 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, W. W., Piazza, C. C., Bowman, L. G., & Amari, A. (1996). Integrating caregiver report with a systematic choice assessment. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 101, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, W. W., Piazza, C. C., Bowman, L. G., & Amari, A. (2021). Evaluación de reforzadores para personas con discapacidad grave, RAISD (J. Virues-Ortega, Trans.). ABA España. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M., Woods, J., & Salisbury, C. (2012). Caregiver coaching strategies for early intervention providers. Infants and Young Children, 25(1), 62–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, E., Gevarter, C., Binger, C., & Hartley, M. (2024). An interprofessional graduate student and family coaching program in naturalistic communication techniques. Seminars in Speech and Language, 45(03), 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gast, D. L., Lloyd, B. P., & Ledford, J. R. (2014). Multiple baseline and multiple probe designs. In Single case research methodology (pp. 251–296). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gevarter, C., Najar, A. M., Flake, J., Tapia-Alvidrez, F., & Lucero, A. (2021). Naturalistic communication training for early intervention providers and Latinx parents of children with signs of autism. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 34(1), 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliam, J. E. (2014). Gilliam autism rating scale (3rd ed.). GARS-3. Pro. Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, M. G. B., & Sobotka, S. A. (2022). Understanding the barriers to receiving autism diagnoses for Hispanic and Latinx families. Pediatric Annals, 51(4), e167–e171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamberger, R. J., Evmenova, A. S., Coogle, C. G., & Regan, K. S. (2022). Parent coaching in natural communication opportunities through bug-in-ear technology. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 42(3), 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, S., Rabagliati, H., Sorace, A., & Fletcher-Watson, S. (2017). Autism and bilingualism: A qualitative interview study of parents’ perspectives and experiences. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 60(2), 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K. R., Stevenson, N. A., & Kauffman, J. M. (2019). CEC division for research position statement: Negative effects of minimum requirements for data points in multiple baseline designs and multiple probe designs in the what works clearinghouse standards handbook (Version 4.0). Council for Exceptional Children Division for Research. Available online: https://cecdr.org/sites/default/files/2021-01/_DR_Position_Statement_5_data_points_WWC_SCD_final.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Kasari, C., Brady, N., Lord, C., & Tager-Flusberg, H. (2013). Assessing the minimally verbal school-aged child with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research, 6(6), 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochwill, T. R., Hitchcock, J. H., Horner, R. H., Levin, J. R., Odom, S. L., Rindskopf, D. M., & Shadish, W. R. (2013). Single-case intervention research design standards. Remedial and Special Education, 34(1), 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanovaz, M. J., & Turgeon, S. (2020). How many tiers do we Need? Type I errors and power in multiple baseline designs. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 43(3), 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, K. A., Kao, B., Plante, W., Seifer, R., & Lobato, D. (2015). Cultural and child-related predictors of distress among Latina caregivers of children with intellectual disabilities. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 120(2), 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, K. (2024). Parent-mediated autism intervention through a culturally informed lens: Parents taking action and pivotal response training with Latine families. Healthcare, 12(23), 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaña, S., Lopez, K., Aguinaga, A., & Morton, H. (2013). Access to diagnosis and treatment services among Latino children with autism spectrum disorders. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 51(3), 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Nieto, L., & Gilbertson, L. (2025). Confidence and preparedness of Wisconsin speech-language pathologists and graduate students in serving bilingual children. Communication Disorders Quarterly. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, M., Soto-Boykin, X., Larson, A., & Julbe-Delgado, D. (2025). Speech-language therapists’ training, confidence, and barriers when serving bilingual children: Development and application of a national survey. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 34(5), 2632–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadan, H., Adams, N. B., Hacker, R. E., Ramos-Torres, S., & Fanta, A. (2020). Supporting Spanish-speaking families with children with disabilities: Evaluating a training and coaching program. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 32(3), 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltenberger, R. G. (2011). Behavior modification: Principles and procedures (5th ed.). Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Minjarez, M. B., Earl, R. K., Bruinsma, Y., & Donaldson, A. L. (2020a). Targeting communication skills. In Y. Bruinsma, M. B. Minjarez, L. Schreibman, & A. C. Stahmer (Eds.), Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions for autism spectrum disorder (1st ed., pp. 237–277). Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Minjarez, M. B., Karp, E. A., Stahmer, A. C., & Brookman-Frazee, L. (2020b). Empowering parents through parent training and coaching. In Y. Bruinsma, M. B. Minjarez, L. Schreibman, & A. C. Stahmer (Eds.), Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions for autism spectrum disorder (1st ed., pp. 77–98). Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Olswang, L. B., & Prelock, P. A. (2015). Bridging the gap between research and practice: Implementation science. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 58(6), S1818–S1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peredo, T. N., Dillehay, K. M., & Kaiser, A. P. (2020). Latino caregivers’ interactions with their children with language delays: A comparison study. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 40(1), 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peredo, T. N., Zelaya, M. I., & Kaiser, A. P. (2018). Teaching low-income Spanish-speaking caregivers to implement EMT en Español with their young children with language impairment: A pilot study. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27(1), 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickard, K., Guerra, K., Hendrix, N., Khowaja, M., & Nicholson, C. (2024). Preliminary outcomes and adaptation of an NDBI for Spanish-speaking families. Journal of Early Intervention, 46(2), 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, L., Light, J., & Laubscher, E. (2024). The effect of naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions and aided AAC on the language development of children on the autism spectrum with minimal speech: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 55, 3078–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakap, S. (2015). Effect sizes as result interpretation aids in single-subject experimental research: Description and application of four nonoverlap methods. British Journal of Special Education, 42(1), 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reszka, S. S., Boyd, B. A., McBee, M., Hume, K. A., & Odom, S. L. (2014). Brief report: Concurrent validity of autism symptom severity measures. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(2), 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieth, S. R., Haine-Schlagel, R., Burgeson, M., Searcy, K., Dickson, K. S., & Stahmer, A. C. (2018). Integrating a parent-implemented blend of developmental and behavioral intervention strategies into speech-language treatment for toddlers at risk for autism spectrum disorder. Seminars in Speech and Language, 39(2), 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollins, P. R., Rangel-Uribe, C., Rojas, R., & Brantley, S. (2024). Examining cultural and linguistic sensitivity of pathways early autism intervention with Hispanic families. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 54(7), 2564–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, C. (2011). Using the communication matrix to assess expressive skills in early communicators. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 32(3), 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, M. M., Meadan, H., Ramos-Torres, S., & Fanta, A. (2023). The cultural and linguistic adaptation of a caregiver-implemented naturalistic communication intervention. Early Childhood Education Journal, 51(1), 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J., Harris, B., McClain, M. B., & Benallie, K. J. (2023). Evaluating psychometric properties of common autism educational identification measures through a culturally and linguistically responsive lens. Psychology in the Schools, 60(2), 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopler, E., Reichle, R. J., & Renner, B. R. (2010). Childhood autism rating scale (2nd ed.). Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow, S. S., Cicchetti, D. V., & Saulnier, C. A. (2016). Vineland adaptive behavior scales (3rd ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrenner, J. R., McIntyre, N., Rentschler, L. F., Pearson, J. N., Luelmo, P., Jaramillo, M. E., Boyd, B. A., Wong, C., Nowell, S. W., Odom, S. L., & Hume, K. A. (2022). Patterns in reporting and participant inclusion related to race and ethnicity in autism intervention literature: Data from a large-scale systematic review of evidence-based practices. Autism, 26(8), 2026–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannest, K. J., & Ninci, J. (2015). Evaluating intervention effects in single-case research designs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93(4), 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannest, K. J., Parker, R. I., Gonen, O., & Adiguzel, T. (2016). Single case research: Web-based calculators for SCR analysis (Version 2.0) [Web-based application]. Texas A&M University. Available online: https://www.singlecaseresearch.org (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- What Works Clearinghouse. (2022). What Works Clearinghouse procedures and standards handbook (Version 5.0). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE).

- Zuckerman, K. E., Lindly, O. J., Reyes, N. M., Chavez, A. E., Macias, K., Smith, K. N., & Reynolds, A. (2017). Disparities in diagnosis and treatment of autism in Latino and non-Latino white families. Pediatrics, 139(5), e20163010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Child | Age | Ethnicity and Gender | Diagnostic Status | CARS-2 or GARS-3 Score | VABS-III Age Equivalents | Communication Matrix Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triad 1 Gustavo | 2;11 | Hispanic male | Independent ASD diagnosis | 34.5 on CARS-2 (mild-to- moderate ASD) | Expressive: 0;11 Receptive: 1;0 | Level 3 (unconventional communication) and Level 4 (conventional gestures) with emerging Level 6 (signs and words) |

| Triad 2 Zandra | 4;3 | Hispanic female | Independent ASD diagnosis | 94 on GARS 3 (Level 2 requiring substantial supports) | Expressive: 1;0 Receptive: 0;6 | Level 3 (unconventional communication) |

| Adult | Age | Ethnicity and Gender | Highest Education Level | Job or Degree Program |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triad 1 Martha (Gustavo’s grandmother) | 72;3 | Hispanic female | Middle School | Retired |

| Triad 1 Nadia (Gustavo’s clinician) | 22;5 | Hispanic female | BA; Master’s degree in progress | Speech-language pathology graduate student |

| Triad 2 Fernanda (Zandra’s mother) | 41;8 | Hispanic female | Postgraduate degree in dentistry | Stay-at-home parent |

| Triad 2 Raquel (Zandra’s clinician) | 28;5 | Hispanic female | BA; Master’s degree in progress | Speech-language pathology graduate student |

| Dimensions | Description | Example(s) of Cultural and Linguistic Adaptations Used |

|---|---|---|

| Language | Use of culturally appropriate language when providing intervention | Recruitment flyers, coaching, and intervention materials provided in the caregiver’s home language; Bilingual student clinicians provided caregiver coaching. |

| Persons | Alignment of race, ethnicity, culture, and language between clinicians and families | Bilingual, bicultural, Spanish-speaking Latina student clinicians provided caregiver coaching |

| Metaphors | Use of common symbols and culturally relevant concepts | Training materials were reviewed by heritage speakers to ensure clear and culturally relevant language |

| Content | Incorporation of cultural values, customs, and traditions within intervention content | Inclusion of additional family members in the program (e.g., Grandmother was interventionist in Triad 1; Mom and dad provided input for Triad 1 during screening, the child’s sister in Triad 2 attended most play sessions alongside the child) to incorporate familismo (cultural concept emphasizing shared family support and decision making); RAISD parent report used to select culturally appropriate materials and routines. |

| Concepts | Culturally and contextually relevant intervention methods | An individualized adaptation for Triad 2 to include mealtime after the mother indicated this was when she interacted most with her child |

| Goals | Ensuring treatment goals align with family priorities and cultural values | Joint planning with families was incorporated into coaching; Researchers had a collaborative discussion with the mother in Triad 2 to determine whether introducing and use of an AAC device aligned family goals. |

| Methods | Integration of cultural knowledge into treatment implementation and procedures | Routines selected based on parent report of child preferences; Joint planning with families incorporated into coaching; Expectations for wait time and modeling language were simplified based on prior research indicating Hispanic families may have challenges with some of these techniques due to cultural mismatch (DuBay et al., 2018; Gallegos et al., 2024; Gevarter et al., 2021; Peredo et al., 2020) |

| Context | Addressing social, economic, and political factors to support cultural sensitivity | Monetary incentives provided; Collaboration between caregivers, researchers and University clinic to assist navigating insurance claims to cover travel and lodging costs to attend program for Triad 2 |

| Adult Targeted Temptations | Example of Child Responses | |

|---|---|---|

| Triad 1 Student Clinician Nadia’s targets for Gustavo | Interrupting routines + carrier phrase (1, 2, _) | Place third finger up (representing three), sign MORE, say tres |

| Items that require assistance | Sign or say ayuda, hand item to adult | |

| Hiding or concealing items | Sign or say ayuda | |

| Triad 1 Gustavo’s Caregiver Martha’s targets | Interrupting routines + carrier phrase (1, 2, _) | Place third finger up (representing three), sign MORE, say tres |

| Giving choices | Touch item, point, or reach | |

| Items that require assistance | Sign or say ayuda, hand item to adult | |

| Triad 2 Student Clinician Raquel’s targets for Zandra | Inadequate portions | Aided (symbols for items), persistent vocalization, guiding adult’s hand |

| Interrupting routines | Aided AAC (symbols for activity), persistent vocalization, guiding adult’s hand | |

| Hiding or concealing items | Aided AAC (symbols for item or activity), persistent vocalization, guiding adult’s hand | |

| Triad 2 Zandra’s Mother Fernanda’s targets | Inadequate portions | Aided AAC (symbols for items), persistent vocalization, guiding adult’s hand |

| Interrupting routines | Aided AAC (symbols for activity) persistent vocalization, guiding adult’s hand | |

| Items requiring assistance | Aided AAC (symbols for activity), persistent vocalization, guiding adult’s hand |

| Learning | Perspective | Behavior | Relationships | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Areas for Improvement | Increase learning opportunities (CG & SC) Provide more Spanish support (SC) | Address negative feelings related to learning new skills in research setting (CG & SC) | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Effectiveness | Positive learning experience (CG & SC) Program’s accessibility (CG) Dedicated time (CG & SC) Proactive and responsive individualized, culturally relevant adult and child learning (CG & SC) Cascade Model (CG & SC) | Benefits of NDBI (CG & SC) | Child Communication Improvement (CG & SC). Increase in adult participants’ use of NDBI strategies (CG & SC) | Positive change in relationship between caregiver and child (CG) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McGuire, R.; Nico, J.; Nattress, N.; Irizarry-Pérez, C.; Gevarter, C. Coaching Bilingual Speech-Language Student Clinicians and Spanish-Speaking Caregivers to Use Culturally Adapted NDBI Techniques with Autistic Preschoolers. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1292. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091292

McGuire R, Nico J, Nattress N, Irizarry-Pérez C, Gevarter C. Coaching Bilingual Speech-Language Student Clinicians and Spanish-Speaking Caregivers to Use Culturally Adapted NDBI Techniques with Autistic Preschoolers. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1292. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091292

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcGuire, Richelle, Jessica Nico, Naomi Nattress, Carlos Irizarry-Pérez, and Cindy Gevarter. 2025. "Coaching Bilingual Speech-Language Student Clinicians and Spanish-Speaking Caregivers to Use Culturally Adapted NDBI Techniques with Autistic Preschoolers" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1292. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091292

APA StyleMcGuire, R., Nico, J., Nattress, N., Irizarry-Pérez, C., & Gevarter, C. (2025). Coaching Bilingual Speech-Language Student Clinicians and Spanish-Speaking Caregivers to Use Culturally Adapted NDBI Techniques with Autistic Preschoolers. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1292. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091292