Treating Young Refugees with a Grief-Focused Group Therapy—A Feasibility Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

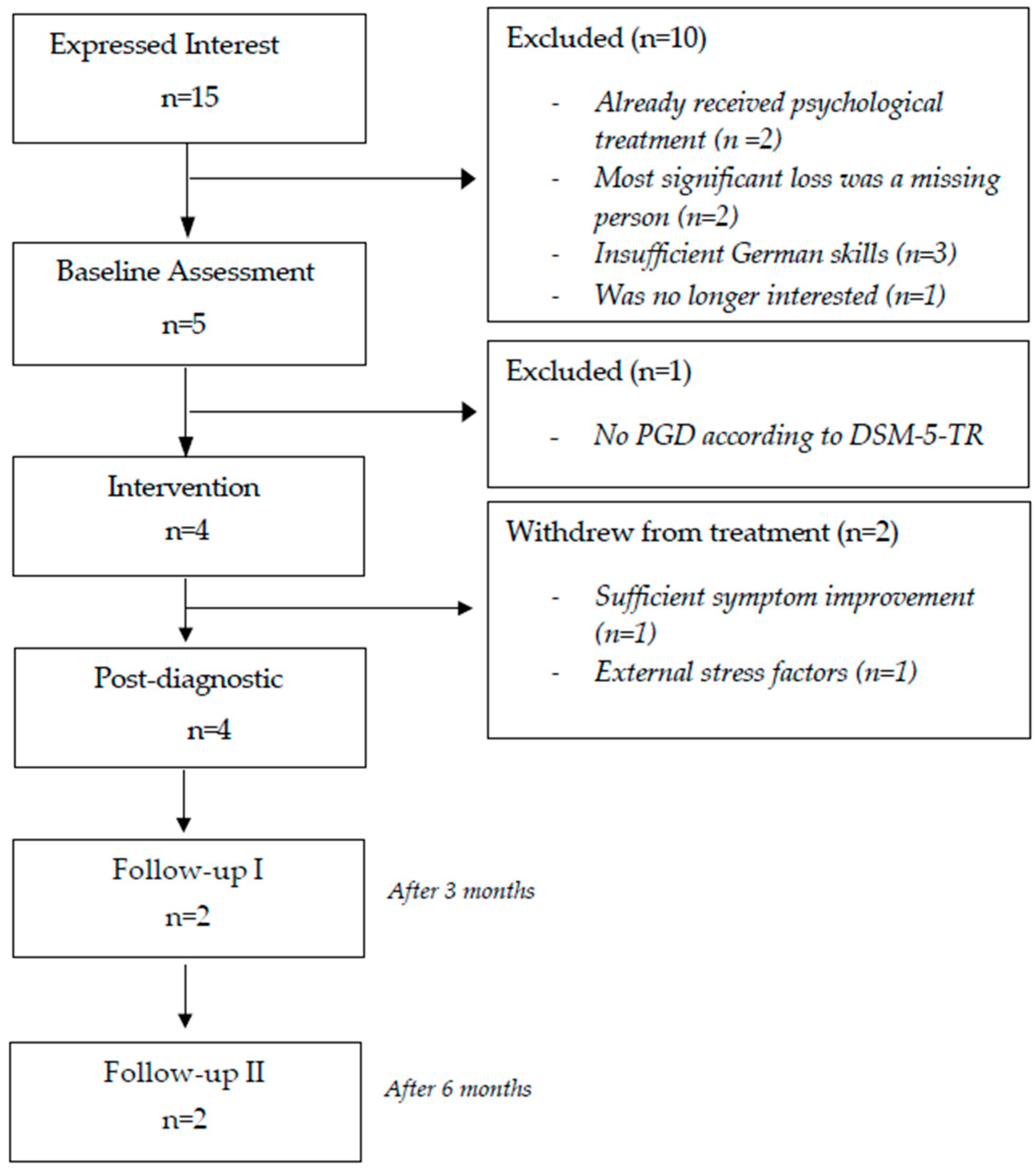

2.1. Sample and Recruitment

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Primary Outcome

2.3.2. Secondary Outcome

2.3.3. Adherence

2.3.4. Participants Perspective on the Intervention and Adverse Events

2.4. Treatment

2.4.1. G-CBT for Refugees

2.4.2. G-CBT Treatment Components

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Outcome Measures

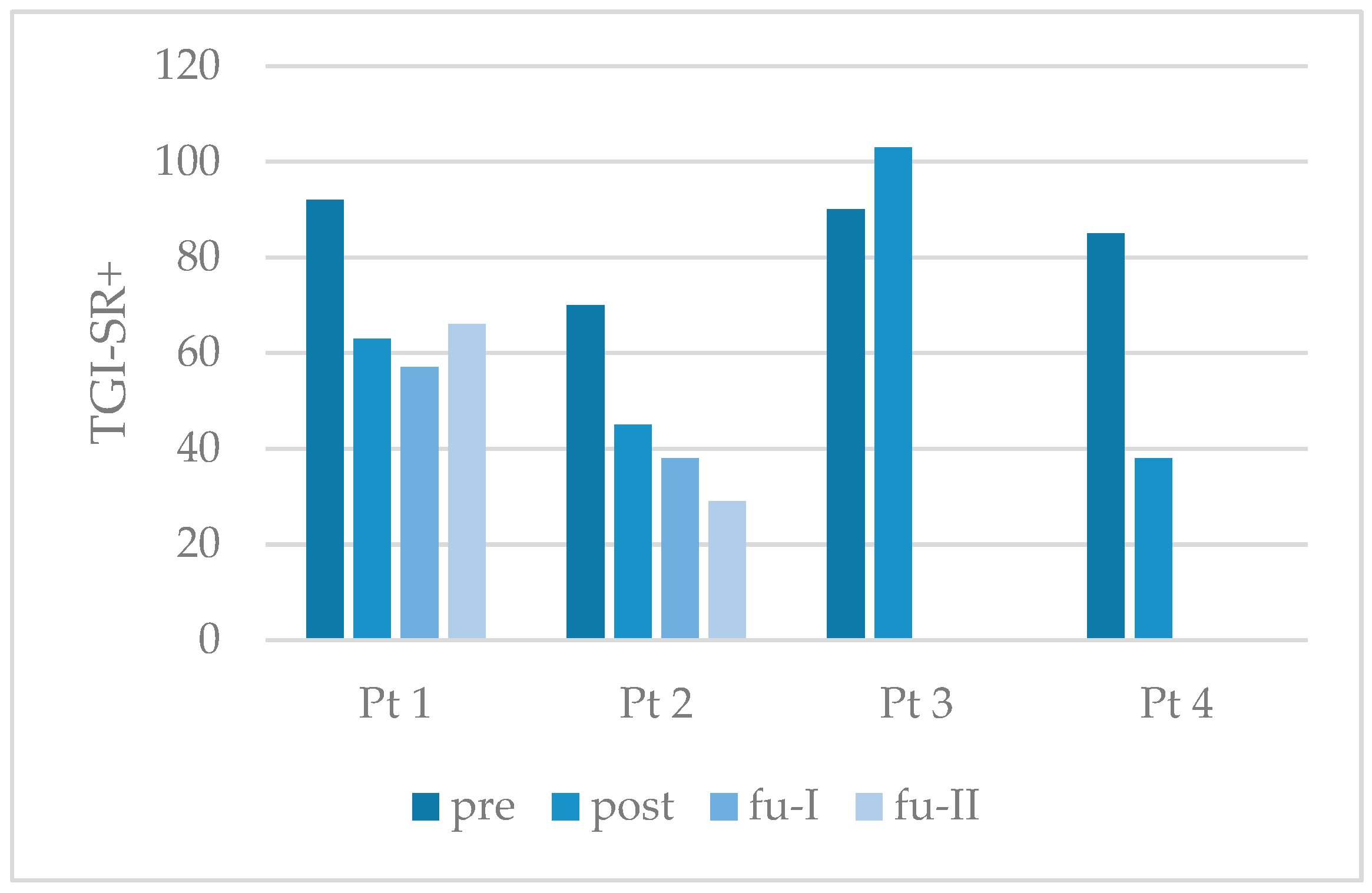

3.2.1. Primary Outcome

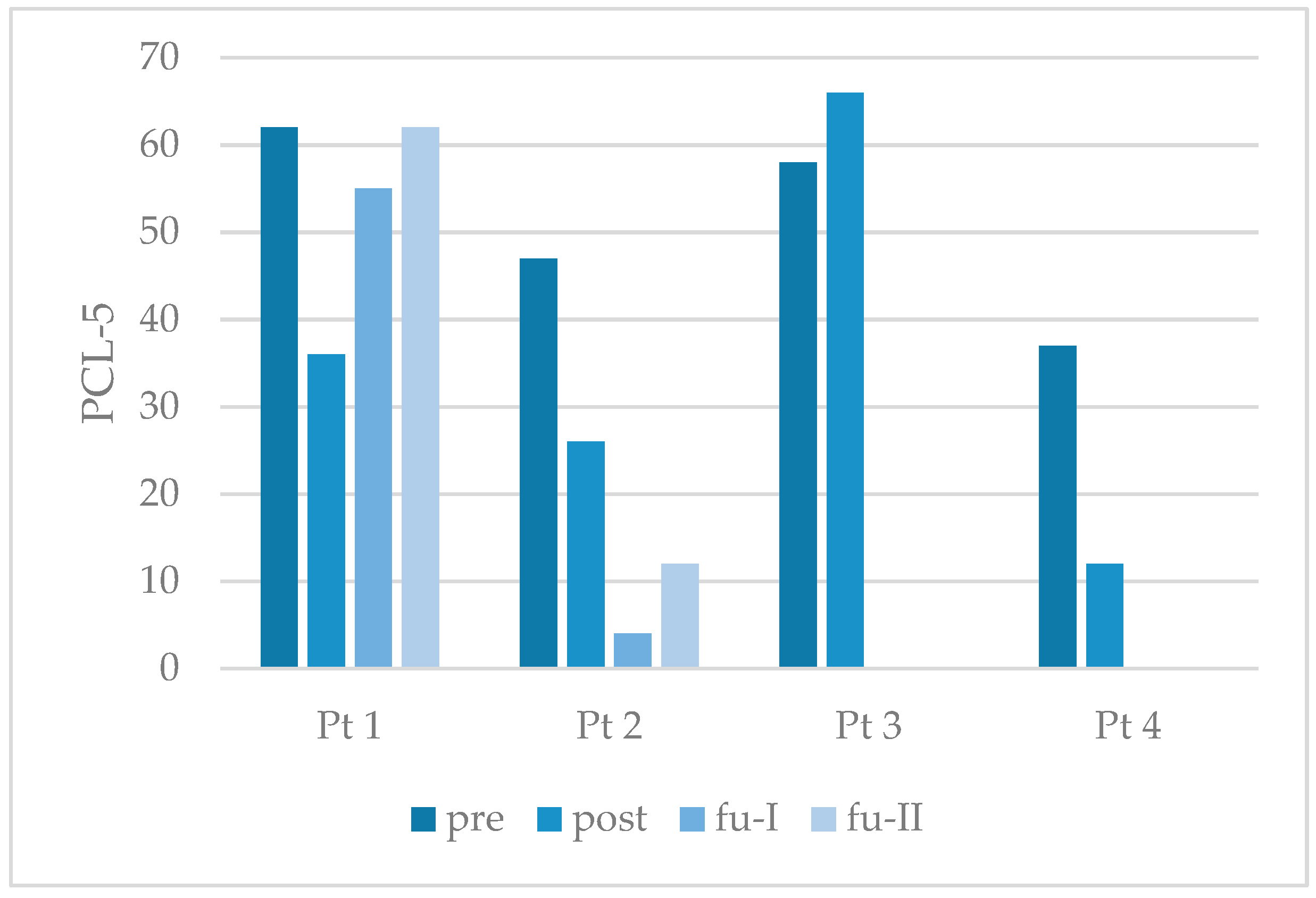

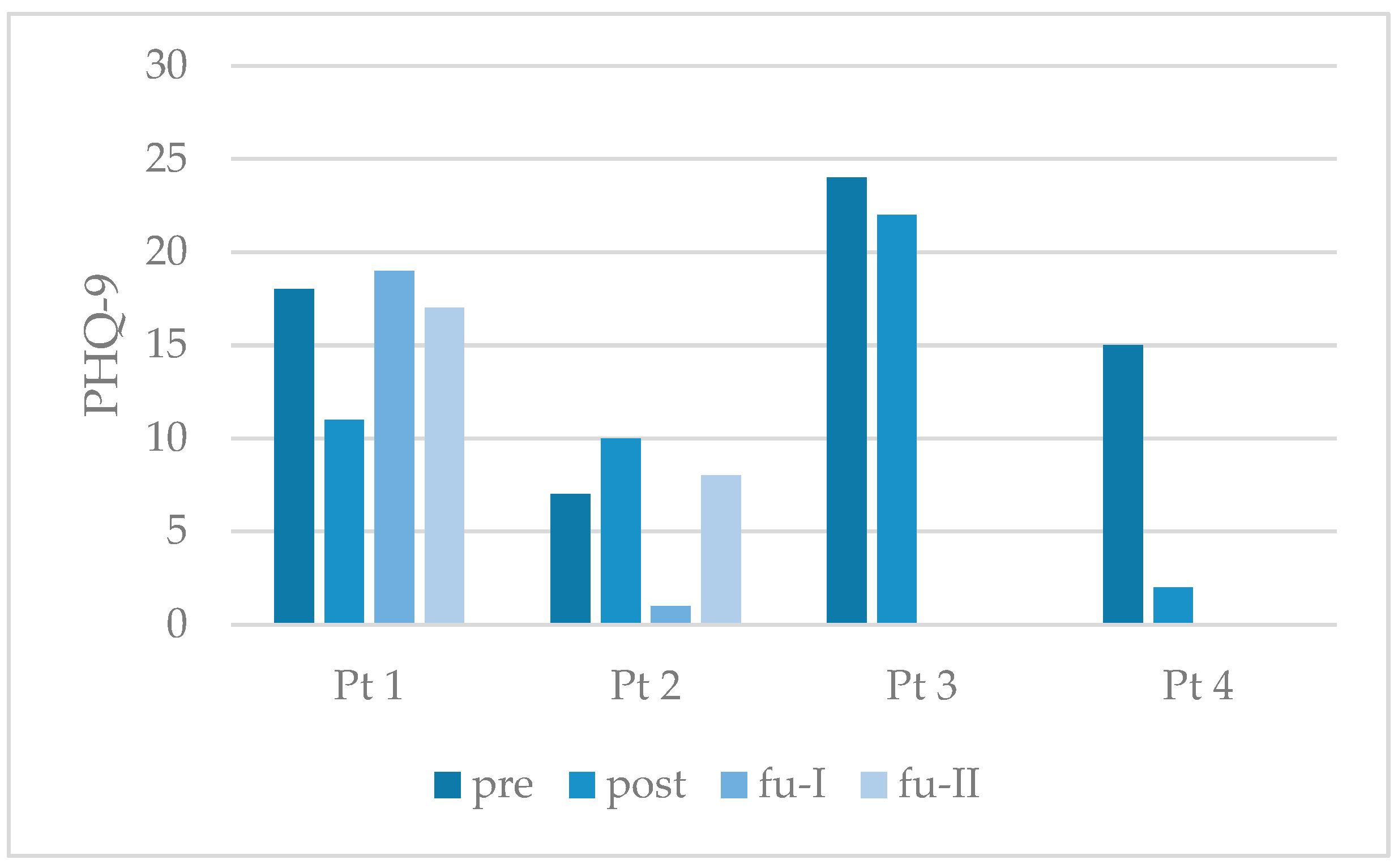

3.2.2. Secondary Outcome

3.3. Feasibility

3.3.1. Dropout and (Serious) Adverse Events

3.3.2. Participants’ Feedback on the Treatment

3.3.3. Barriers to Recruitment and Treatment Administration

3.3.4. Adherence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PGD | Prolonged Grief Disorder |

| G-CBT | Grief-focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

| DSM-5-TR | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition, Text Revision |

| ICD-10/11 | International Classification of Diseases, 10th/11th Revision |

| PTSD | Posttraumatic Stress Disorder |

| UNHCR | United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees |

| CYW | Child and Youth Welfare |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| CBT | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

| PCBD | Persistent Complex Bereavement Disorder |

| BEP-TG | Brief Eclectic Psychotherapy for Traumatic Grief |

| PG-13-R | Prolonged Grief Disorder 13 Revised Scale |

| Pre | Before the treatment |

| Post | After the treatment |

| Fu-I | Three months after the treatment |

| Fu-II | Six months after the treatment |

| TGI-SR+ | Traumatic Grief Inventory Self Report Plus |

| Mini-DIPS | Diagnostic Short Interview of Mental Disorder |

| LEC-5 | Life Event Checklist for DSM-5 |

| PCL-5 | Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 |

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 |

| PMR | Progressive Muscle Relaxation |

| RCI | Reliable Change Index |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

References

- Aeschlimann, A., Heim, E., Killikelly, C., Arafa, M., & Mearcker, A. (2024). Culturally sensitive grief treatment and support: A scoping review. SSM Mental Health, 5, 100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeschlimann, A., Heim, E., Killikelly, C., Mahmoud, N., Haji, F., Stoeckli, R. T., Aebersold, M., Thoma, M., & Maercker, A. (2025). Cultural adaption of a self-help app for grieving Syrian refugees in Switzerland. A feasibility and acceptability pilot-RCT. Internet Interventions, 39, 100800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA—American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders—Text revision (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- BAfF—Bundesweite Arbeitsgemeinschaft für psychosoziale Zentren für Flüchtlinge und Folteropfer. (2025). Flucht & gewalt: Psychosozialer versorgungsbericht deutschland 2025, fokus grenzgewalt. Available online: https://www.baff-zentren.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/BAfF_VB2025.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- BAMF—Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge. (2024). Das bundesamt in zahlen 2023. Asyl, migration und integration. Available online: https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Statistik/BundesamtinZahlen/bundesamt-in-zahlen-2023.html (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Bird, V., Le Boutillier, C., Leamy, M., Williams, J., Bradstreet, S., & Slade, M. (2014). Evaluating the feasibility of complex interventions in mental health services: Standardised measure and reporting guidelines. British Journal of Psychiatry, 204, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, R., Gray, K. M., Boyle, J. A., Fazel, M., Ranasinha, S., Fitzgerald, G., Misso, M., & Gibson-Helm, M. (2020). Systematic review and meta-analysis: The prevalence of mental illness in child and adolescent refugees and asylum seekers. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(6), 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blampied, N. M. (2022). Reliable change and the reliable change index: Still useful after all these years? The Cognitive Behavior Therapist, 15(50), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMAS—Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales. (2014). Leichte sprache. Ein ratgeber. Available online: https://www.bmas.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Publikationen/a752-ratgeber-leichte-sprache.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=8 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Boelen, P. A., de Keijser, J., van den Hout, M. A., & van den Bout, J. (2007). Treatment of complicated grief: A comparison between cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counseling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(2), 227–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettcher, V. S., & Neuner, F. (2022). The impact of an insecure asylum status on mental health of adult refugees in Germany. Clinical Psychology in Europe, 4(1), e6587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohus, M., & Wolf-Ahrehult, M. (2018). Interaktives skillstraining für borderline-patienten. Das therapeutenmanual. Schattauer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Burr, C., Zachariae, R., Komischke-Konnerup, K. B., Marello, M. M., Schierff, L. H., & O’Connor, M. (2024). Risk factors for prolonged grief symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 107, 102375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comtesse, H., & Rosner, R. (2019). Prolonged grief disorder among asylum seekers in Germany: The influence of losses and residence status. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10, 1591330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comtesse, H., Smid, G. E., Rummel, A.-M., Spreeuwenberg, P., Lundorff, M., & Dückers, M. L. A. (2024). Cross-national analysis of the prevalence of prolonged grief disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 350, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel-Calveras, A., Baldqaui, N., & Baeza, I. (2022). Mental health of unaccompanied refugee minors in Europe: A systematic review. Child Abuse & Neglect, 133, 105865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Heus, A., Hengst, S. M., de la Rie, S. M., Djelantik, A. A. A. M. J., Boelen, P. A., & Smid, G. E. (2017). Day patient treatment for traumatic grief: Preliminary evaluation of a one-year treatment programme for patients with multiple and traumatic losses. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(1), 1375335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djelantik, A. A. A. M. J., deHeus, A., Kuiper, D., Kleber, R. J., Boelen, P. A., & Smid, G. E. (2020). Post-migration stressors and their association with symptom reduction and non-completion during treatment for traumatic grief in refugees. Frontier in Psychiatry, 11, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djelantik, A. A. A. M. J., van Es, C. M., Lahuis, A. M., & Mooren, N. (2024). The challenges of conducting mental health research among resettled refugee populations: An ecological framework from a researchers’ perspective. International Journal of Mental Health, 53(1), 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumke, L., Wilker, S., Hecker, T., & Neuner, F. (2024). Barriers to accessing mental health care for refugees and asylum seekers in high-income countries: A scope review of reviews mapping demand and supply-side factors onto a conceptual framework. Clincal Psychology Review, 113, 102491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehring, T., Knaevelsrud, C., Krüger, A., & Schäfer, I. (2014). German version of the life events checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5) and the PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Available online: https://www.zep-hh.de/files/zep/pdf/PCL-5-with-LEC_German.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Ellis, A. (1991). The revised ABC’s of rational-emotive therapy (RET). Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy 9(3), 139–172. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. (2024). Asylum applications—Annual statistics. statistics explained. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?oldid=599145 (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Genton, P. C., Wang, J., Bodenmann, P., & Ambresin, A.-E. (2022). Clinical profile and care pathways among unaccompanied minors asylum seekers in Vaud, Switzerland. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 34(3), 20190140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanauer, C., Telaar, B., Rosner, R., & Doering, B. K. (2024). The efficacy of psychosocial interventions for grief symptoms in bereaved children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 350, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heeke, C., Kampisiou, C., Niemeyer, H., & Knaevelsrud, C. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of correlates of prolonged grief disorder in adults exposed to violent loss. European Journal of Psychotraumatol, 10, 1583524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hengst, S. M. C., Smid, G. E., & Laban, C. J. (2018). The effects of traumatic und multiple loss in psychotraumathology, disability, and quality of life in Iraqi asylum seekers in the Netherlands. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 206(1), 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennemann, S., Killikelly, C., Hyland, P., Maercker, A., & Witthöft, M. (2023). Somatic symptom distress and ICD-11 prolonged grief in large intercultural sample. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 14(2), 2254584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilberdink, C. E., Ghainder, K., Dubanchet, A., Hinton, D., Djelantik, A. A. A. M. J., Hall, B. J., & Bui, E. (2023). Breavement issues and prolonged grief disorder: A global perspective. Ambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health, 10(e32), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjern, A., & Kling, S. (2019). Health care needs in school-age refugee children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16, 4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornfeck, F., Eglinsky, J., Garbade, M., Rosner, R., Kindler, H., Pfeiffer, E., & Sachser, C. (2023). Mental health problems in unaccompanied young refugees and the impact of post-flight factors on PTSS, depression and anxiety—A secondary analysis of the Better Care study. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1149634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, R., King, N., & Majumder, P. (2022). How effective is group intervention in the treatment for unaccompanied and accompanied refugee minors with mental health difficulties: A systematic review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 68(3), 484–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, N. S., & Truax, P. (1991). Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalantari, M., Yule, W., Dyregrov, A., Neshatdoost, H. A., & Ahmadi, S. J. (2012). Efficacy of writing for recovery on traumatic grief symptoms of afghani refugee bereaved adolescents: A randomized control trial. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 65(2), 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, P. C., Marrs-Garcia, A., Nath, S. R., & Sheldrick, R. C. (1999). Normative comparisons for the evaluation of clinical significance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(3), 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokou-Kpolou, C. K., Lenferink, L. I. M., Brunnet, A. E., Park, S., Megalakaki, O., Boelen, P., & Cénat, J. M. (2022). The ICD-11 and DSM-5-TR prolonged grief criteria: Validation of the Traumatic Grief Inventory-Self Report Plus using exploratory factor analysis and item response theory. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 29, 1950–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokou-Kpolou, C. K., Moukouta, C. S., Masson, J., Bernoussi, A., Cénat, J. M., & Bacqué, M. F. (2020). Correlates of grief-related disorders and mental health outcomes among adult refugees exposed to trauma and bereavement: A systematic review and future research directions. Journal of Affective Disorders, 267, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komischke-Konnerup, K. B., Zachariae, R., Boelen, P. A., Marello, M. M., & O’Connor, M. (2024). Grief-focused cognitive behavioral therapies for prolonged grief symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 92(4), 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komischke-Konnerup, K. B., Zachariae, R., Johannsen, M., Nielsen, L. D., & O’Connor, M. (2021). Co-occurrence of prolonged grief symptoms and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress in bereaved adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorder Report, 4, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9. Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger-Gottschalk, A., Knaevelsrud, C., Rau, H., Dyer, A., Schäfer, I., Schellong, J., & Ehring, T. (2017). The German version of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Psychometric properties and diagnostic utility. BMC Psychiatry, 17, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner-Meichsner, F., & Comtesse, H. (2022). Beliefs about causes and cures of prolonged grief disorder among Arab and Sub-Saharan African refugees. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 852714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner-Meichsner, F., Comtesse, H., & Olk, M. (2024). Prevalence, comorbidities, and factors associated with prolonged grief disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder and complex posttraumatic stress disorder in refugees: A systematic review. Conflict and Health, 18, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenferink, L. I. M., Eisma, M. C., Smid, G. E., de Keijser, J., & Boelen, P. A. (2022). Valid measurement of DSM-5 persistent complex bereavement disorder and DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 prolonged grief disorder: The Traumatic Grief Inventory-Self Report Plus (TGI-SR+). Comprehensive Psychiatry, 112, 152281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobb, E. A., Kristjanson, L. J., Aoun, S. M., Monterosso, L., Halkett, G. K. B., & Davies, A. (2010). Predictors of complicated grief: A systematic review of empirical studies. Death Studies, 34(8), 678–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundorff, M., Holmgren, H., Zachariae, R., Farver-Vestergaard, I., & O’Connor, M. (2017). Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in adult bereavement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 212, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margraf, J., Cwik, J. C., Pflug, V., & Schneider, S. (2017). Strukturierte klinische Interviews zur Erfassung psychischer Störungen über die Lebensspanne. Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie, 46(3), 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittendorfer-Rutz, E., Hagström, A., & Hollander, A. C. (2020). High suicide rates among unaccompanied minors/youth seeking asylum in sweden. Crisis, 41(4), 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, A., Byrow, Y., O’Donnell, M., Mau, V., McMahon, T., Pajak, R., Li, S., Hamiltion, A., Minihan, S., Liu, C., Bryant, R. A., Berle, D., & Liddell, B. J. (2019). The association between visa insecurity and mental health, disability and social engagement in refugees living in Australia. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10, 1688129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutsch, N., & Bozorgmehr, K. (2020). Der Einfluss postmigratorischer Stressoren auf die Prävalenz depressiver Symptome bei Geflüchteten in Deutschland. Analyse anhand der IAB-BAMF-SOEP-Befragung 2016. Bundesgesundheitsblatt—Gesundheitsforschung—Gesundheitsschutz, 63(12), 1470–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patanè, M., Ghane, S., Karyotaki, E., Cuijpers, P., Schoonmade, L., Tarsitani, L., & Sijbrandij, M. (2022). Prevalence of mental disorders in refugees and asylum seekers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health, 14(9), 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, E., Sachser, C., Rohlmann, F., & Goldbeck, L. (2018). Effectiveness of a trauma-focused group intervention for young refugees: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 59(11), 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigerson, H. G., Boelen, P. A., Xu, J., Smith, K. V., & Maciejewski, P. K. (2021). Validation of the new DSM-5-TR criteria for prolonged grief and the PG-13-Revised (PG-13-R) scale. World Psychiatry, 20, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosner, R., Hagl, M., Bücheler, L., & Comtesse, H. (2022). Homesickness in asylum seekers: The role of mental health and migration-related factors. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 1034370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosner, R., Lumbeck, G., & Geissner, E. (2011). Effectiveness of an inpatient group therapy for comorbid complicated grief disorder. Psychotherapy Research, 21(2), 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosner, R., Pfoh, G., Rojas, R., Brandstätter, M., Rossi, R., Lumbeck, G., Kotoučová, M., Hagl, M., & Geissner, E. (2015). Anhaltende trauerstörung. Manuale für die einzel- und gruppentherapie. Hogrefe Verlag.

- Rummel, A.-M., Vogel, A., Rosner, R., & Comtesse, H. (2023). Grief-focused cognitive behavioral group therapy (G-CBT). Unpublished manual. Department of Psychology, Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt. [Google Scholar]

- Semmlinger, V., & Ehring, T. (2021). Predicting and preventing dropout in research, assessment and treatment with refugees. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 29, 767–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smid, G. E., Hengst, S., de la Rie, S. M., Bos, J. B. A., Gersons, B. P. R., & Boelen, P. A. (2021). Brief eclectic psychotherapy for traumatic grief (BEP-TG). [Unpublished manual. ARQ Centrum ’45].

- Smid, G. E., Kleber, R. J., de la Rie, S. M., Bos, J. B. A., Gersons, B. P. R., & Boelen, P. A. (2015). Brief Eclectic Psychotherapy for Traumatic Grief (BEP-TG): Toward integrated treatment of symptoms related to traumatic loss. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6, 27324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M. V. A., Grohmann, D., & Trivedi, D. (2023). Use of social media in recruiting young people to mental health research: A scoping review. BMJ Open, 13, e075290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, A. K., Mung, H. K., Badrudduza, M., Balasundaram, S., Azim, D. F., Zaini, N. A., Morgan, K., Mohsin, M., & Silove, D. (2020). Psychosocial mechanisms of change in symptoms of persistent complex bereavement disorder amongst refugees from Myanmar over the course of integrative adapt therapy. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1807170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR—The UN Refugee Agency. (2024). Global report 2023—Executive summary. Available online: https://reporting.unhcr.org/global-report-2023-executive-summary (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Vogel, A., Comtesse, H., Nocon, A., Kersting, A., Rief, W., Steil, R., & Rosner, R. (2021). Feasibility of present-centered therapy for prolonged grief disorder: Results of a pilot study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 534664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weathers, F. W., Blake, D. D., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Marx, B. P., & Keane, T. M. (2013). The life events checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5)—Standard. Available online: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Wiechers, M., Strupf, M., Bajbouj, M., Böge, K., Karnouk, C., Goerigk, S., Kamp-Becker, I., Banaschewski, T., Rapp, M., Hasan, A., Falkai, P., Jobst-Heel, A., Habel, U., Stamm, T., Heinz, A., Hoell, A., Burger, M., Bunse, T., Hoehne, E., … Padberg, F. (2023). Empowerment group therapy for refugees with affective disorders: Results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial. European Psychiatry, 66(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojtkowiak, J., Lind, J., & Smid, G. E. (2021). Ritual in therapy for prolonged grief: A scoping review of ritual elements in evidence-informed grief interventions. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 623835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Znoj, H.-J. (2004). Komplizierte trauer. Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

| Participant | Brief Case History | Categorical Diagnosis | Deceased/Significant Loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The young refugee is living in a CYW facility. He reports several deaths and mentions five by name, all unnatural deaths either by murder or accident; he has contact with his family in his home country. He went to school in Germany and his asylum application was approved at the end of treatment. | PGD Major depression PTSD Current and lifetime no suicidal ideation; | Relative Murdered Unexpected death 8 months since the loss |

| 2 | The young refugee is living in a CYW facility. He reports several deaths and mentions two by name, one from illness and one from war; he has contact with his family in his home country. At the beginning of treatment, he started with school, and he applied for asylum. | PGD Major depression PTSD No suicidal ideation; death wishes in the past. | Friend Death by a bomb Unexpected death 36 months since the loss |

| 3 | The young refugee is living in a CYW facility. He reports two deaths, both unexpected but natural; he has no family left. He was in vocational school and has residency permits. | PGD Major depression PTSD Participant had suicidal thoughts before treatment but credibly distanced himself from suicidal thoughts and attempts during treatment. | Parent Death by illness Unexpected death 21 months since the loss |

| 4 | The young refugee is living in a CYW facility. He reports two deaths, one from illness and one from war—he was present at both deaths. At the beginning of treatment, he went to school. His asylum application was approved during the treatment. | PGD Major depression PTSD Self-harm and suicidal thoughts in the past, currently credibly distanced | Relative Death by illness Unexpected death 12 months since the loss |

| Treatment Phase (Session Numbers) | Focus Topics | Treatment Strategies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Introduction and psychoeducation (1–3) | Building motivation | Psychoeducation on psychotherapy; group rules; personal therapy goals | |

| Characteristics and consequences of my grieving process | Reflection on the participants’ own grieving process; common mid- and long-term consequences of grieving | ||

| Cultural differences in grieving | Cultural variations in mourning practices and rituals; open non-judgmental reflection on traditions, temporal aspects, attire, religious belief, etc., regarding grief. | ||

| Development of PGD | Difference between integrated and prolonged grief using an adapted and simplified version of the grief model according to Znoj (2004). | ||

| Symptoms and coping | Coping attempts to deal with the current situation; symptoms as dysfunctional coping attempts. | ||

| Sleep hygiene | Introduction of sleep hygiene strategies. | ||

| Emotions (4–5) | Psychoeducation on emotions | Introduction of the main emotions and emotions’ functions (e.g., providing information about the situation, expression, messages, etc.). | |

| Emotion regulation and skills | Suppression of emotions and problem behavior; emotion regulation; theoretical information and practical use of skills according to DBT (Bohus & Wolf-Ahrehult, 2018). | ||

| Rumination and problem solving | Difference between rumination and problem solving; (dys-)functionality of rumination in PGD. | ||

| Strategies to deal with rumination behavior | Anti-rumination strategies such as “rumination stop”, “best friends trick”, “worry time”, “conscious memorial time”, “radical acceptance”. | ||

| Avoidance and exposure (6–9) | Avoidance in PGD (Avoidance types) | Psychoeducation on avoidance in PGD; introducing four types of avoidance: “avoiding the reality of loss/emotions”, “avoiding certain situations or objects”, “avoiding memories of certain events” and “holding on to grief behavior” with example stories (BEP-TG; Smid et al., 2015, 2021). | |

| Functionality of avoidance | Functionality of the introduced PGD avoidance types; reflection on one’s own avoidance behavior and functionality of it. | ||

| Reducing avoidance behavior | Approaches to reduce avoidance, depending on type. | ||

| Presentation of the deceased person | Participants introduce their deceased person and what made him/her special to them by presenting pictures, stories, collages etc. | ||

| Exposure (Individual Session) | Individual approach depends on the most dominant avoidance type. | ||

| Avoidance type | Exposure | ||

| Avoiding the reality of loss/emotions | Allowing grief (recall memories) | ||

| Avoiding certain situations or objects | In vivo (confrontation with situations/objects) | ||

| Avoiding memories of certain events | In sensu (confrontation with the worst moment) | ||

| Holding on to grief behavior | Reduction in grief behavior (reflection of the grieving behavior; planning the grieving process); building alternative behaviors. | ||

| Cognitive restructuring (10–11) | Psychoeducation on dysfunctional thoughts | Psychoeducation on dysfunctional thoughts and the relationship between thoughts, emotions and behavior; introduction to the ABC scheme based on Ellis (1991). | |

| Restructuring | Restructuring of grief related dysfunctional thoughts in the group; individual restructuring with worksheets; discussing different restructuring possibilities in the group | ||

| My plan for difficult times | Planning for difficult upcoming events such as birthdays, holidays etc. | ||

| Conclusion (12) | My future | Changes due to treatment; experiences of growth; imagine the future. | |

| Importance of rituals | Diversity of rituals; participants reflect on advantages of individual grieving rituals; finding an individual grieving ritual for each participant. | ||

| Collective grieving ritual | The group closes with a collective grieving ritual to say farewell to the deceased. | ||

| Difference in Total Values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant | Outcome | Pre-Post | Pre-fu-I | Pre-fu-II |

| 1 | TGI-SR+ | 29 * | 35 * | 26 * |

| PCL-5 | 26 * | 7 | 0 | |

| PHQ-9 | 7 * | −1 | 1 | |

| 2 | TGI-SR+ | 25 * | 32 * | 41 * |

| PCL-5 | 21 * | 43 * | 35 * | |

| PHQ-9 | −3 | 6 | −1 | |

| 3 | TGI-SR+ | −13 | ||

| PCL-5 | −8 | |||

| PHQ-9 | 2 | |||

| 4 | TGI-SR+ | 47 * | ||

| PCL-5 | 25 * | |||

| PHQ-9 | 13 * | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rummel, A.-M.; Vogel, A.; Rossi, R.; Jacob, M.; Achtner, M.; Schnauder, J.; Rosner, R.; Comtesse, H. Treating Young Refugees with a Grief-Focused Group Therapy—A Feasibility Trial. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091285

Rummel A-M, Vogel A, Rossi R, Jacob M, Achtner M, Schnauder J, Rosner R, Comtesse H. Treating Young Refugees with a Grief-Focused Group Therapy—A Feasibility Trial. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091285

Chicago/Turabian StyleRummel, Anna-Maria, Anna Vogel, Ruth Rossi, Melanie Jacob, Michael Achtner, Julia Schnauder, Rita Rosner, and Hannah Comtesse. 2025. "Treating Young Refugees with a Grief-Focused Group Therapy—A Feasibility Trial" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091285

APA StyleRummel, A.-M., Vogel, A., Rossi, R., Jacob, M., Achtner, M., Schnauder, J., Rosner, R., & Comtesse, H. (2025). Treating Young Refugees with a Grief-Focused Group Therapy—A Feasibility Trial. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091285