Internet-Delivered Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (iCBT) for Spanish-Speaking Adults with Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD): A Randomized Feasibility Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

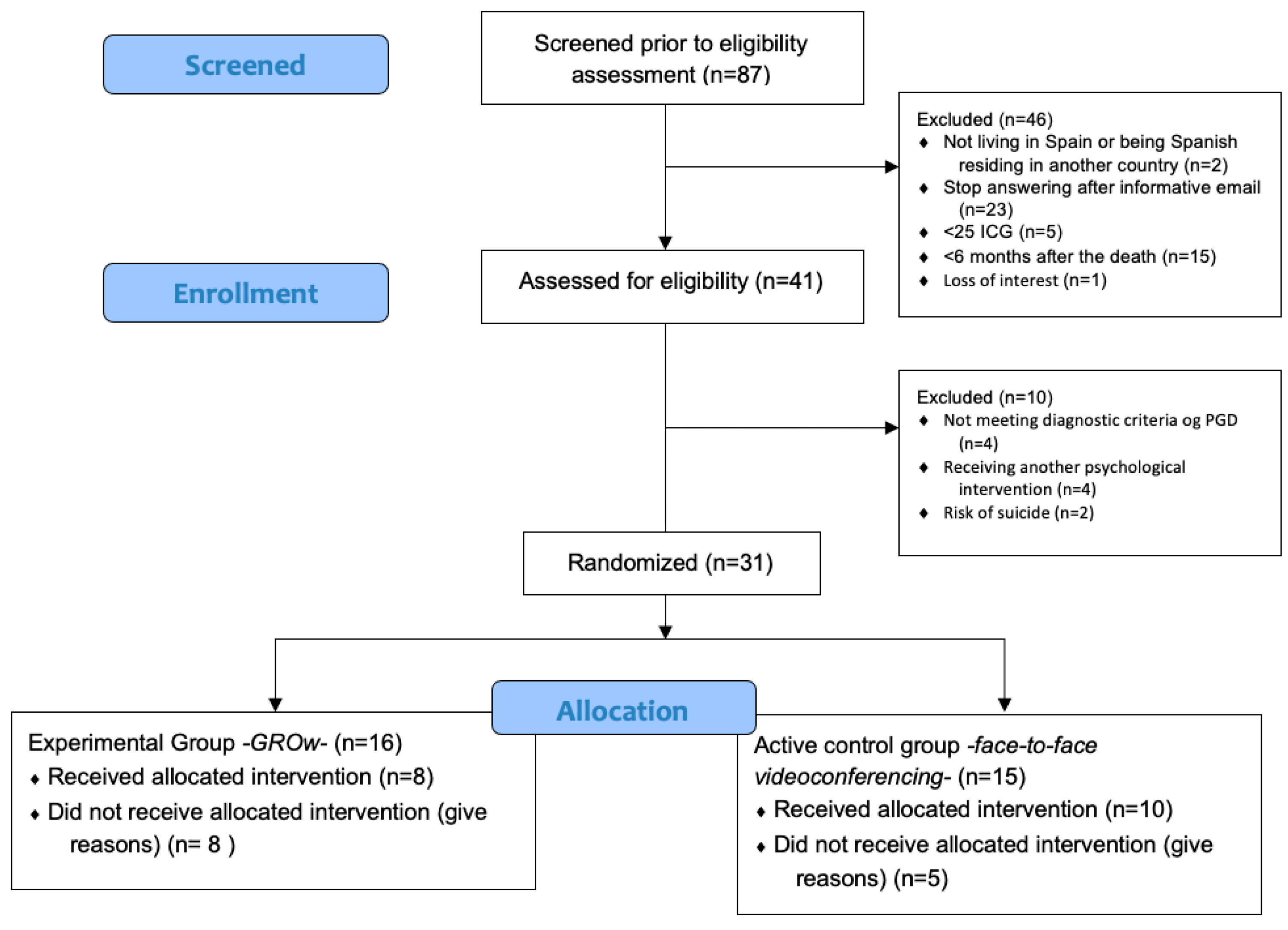

2.2. Recruitment, Screening, and Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Intervention

2.3.1. Therapeutic Components

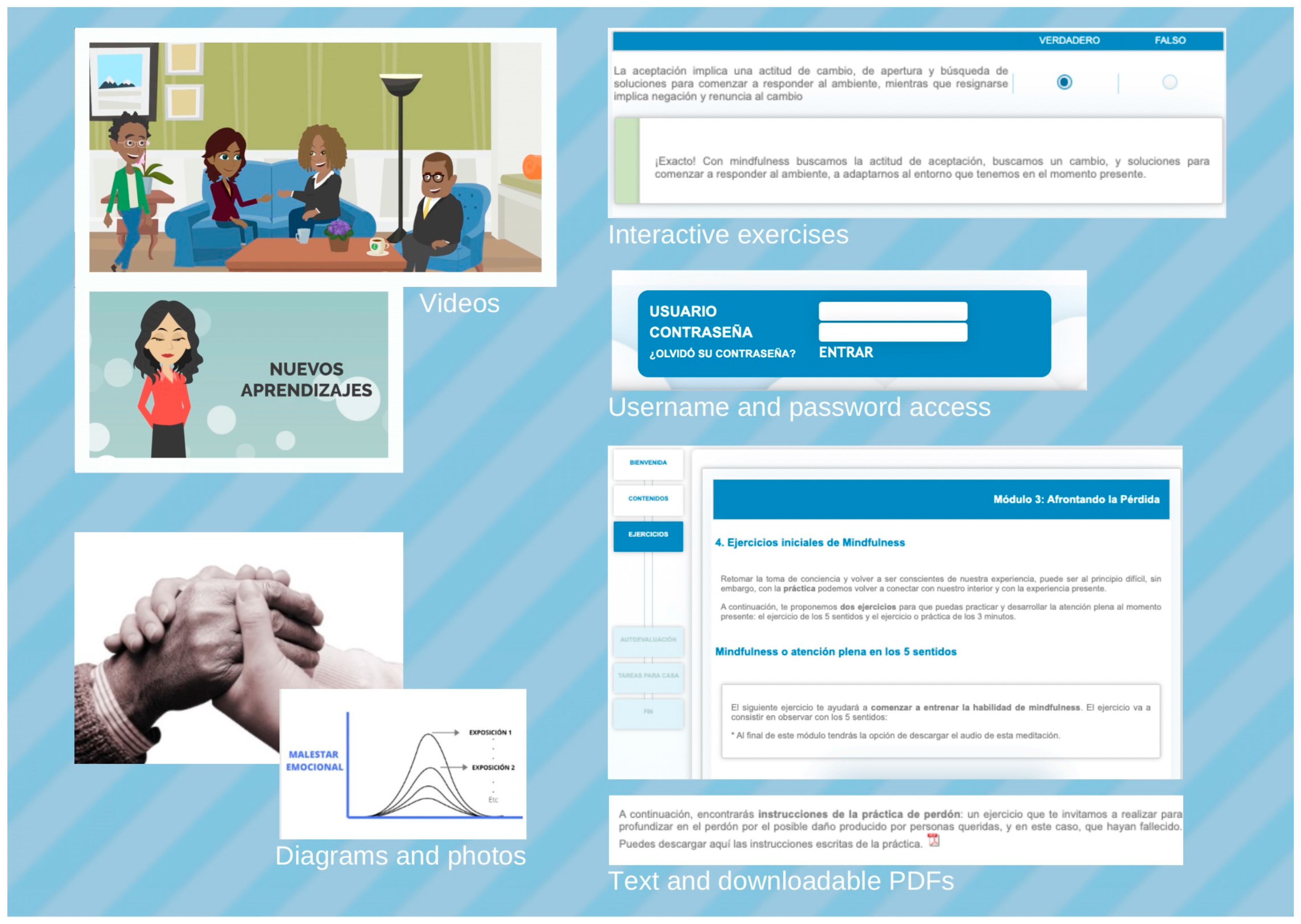

2.3.2. iCBT for PGD (GROw)

2.3.3. Videoconferencing Treatment

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.4.1. Screening, Diagnostic Measures and Demographics

2.4.2. Primary Outcomes: Measures of Feasibility

2.4.3. Psychological and Mental Health Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline and Participant Characteristics

3.2. Feasibility Results

3.2.1. Participants Recruitment Process and Adherence

3.2.2. Preferences and Opinions When Comparing the Two Types of Intervention Formats

3.2.3. Expectations and Satisfaction

3.2.4. Qualitative Interview

4. Discussion

4.1. Recruitment

4.2. Adherence and Dropouts

4.3. Preferences and Opinions

4.4. Expectations, Satisfaction, and Participants’ Evaluation About the Usefulness of the Intervention

4.5. Potential Efficacy

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Outcome | Pre | Post | t | p | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | ||||

| IGC | 45.88 | 4.53 | 36.25 | 5.30 | 3.48 | 0.010 | 1.23 |

| BDI-II | 31.75 | 4.20 | 17.13 | 3.39 | 4.55 | 0.003 | 1.61 |

| TBQ | 68.00 | 4.40 | 51.38 | 5.87 | 5.27 | 0.001 | 1.86 |

| OASIS | 10.88 | 1.75 | 7.13 | 1.68 | 3.84 | 0.006 | 1.36 |

| ODSIS | 11.25 | 1.70 | 8.50 | 1.18 | 1.98 | 0.088 | 0.70 |

| PANAS | |||||||

| Positive Affect | 17.13 | 2.12 | 22.00 | 2.27 | 4.16 | 0.004 | 1.47 |

| Negative Affect | 28.00 | 3.68 | 21.50 | 2.25 | 2.26 | 0.058 | 0.80 |

| WSAS | 20.63 | 3.63 | 20.00 | 4.64 | 0.29 | 0.779 | 0.10 |

| QLI | 3.91 | 0.64 | 4.92 | 0.67 | 3.84 | 0.006 | 1.36 |

| PTGI | 28.25 | 4.60 | 42.63 | 7.72 | 2.72 | 0.030 | 0.59 |

| PIL-10 | 33.13 | 3.46 | 39.25 | 2.64 | 2.89 | 0.023 | 1.02 |

| FFMQ-15 | |||||||

| Observe | 2.83 | 0.34 | 2.75 | 0.34 | −0.55 | 0.598 | −0.19 |

| Describe | 3.62 | 0.38 | 3.33 | 0.39 | −0.70 | 0.505 | −0.25 |

| Awareness | 3.00 | 0.33 | 3.08 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.763 | 0.11 |

| No judgment | 2.75 | 0.41 | 3.42 | 0.31 | 1.79 | 0.117 | 0.63 |

| No reactivity | 2.79 | 0.25 | 2.83 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.763 | 0.11 |

| SCS-SF | |||||||

| Self-compassion | 2.25 | 0.34 | 2.66 | 0.27 | 1.69 | 0.135 | 0.60 |

| Common humanity | 2.81 | 0.26 | 3.03 | 0.26 | 0.70 | 0.456 | 0.28 |

| Mindfulness | 2.69 | 0.30 | 2.44 | 0.26 | −1.10 | 0.306 | −0.39 |

| Outcome | Pre | Post | t | p | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | ||||

| IGC | 40.43 | 3.96 | 21.43 | 6.03 | 5.62 | 0.001 | 2.12 |

| BDI-II | 24.29 | 4.29 | 9.57 | 3.58 | 6.16 | <0.001 | 2.33 |

| TBQ | 54.71 | 7.78 | 35.86 | 8.65 | 4.42 | 0.004 | 1.67 |

| OASIS | 10.14 | 1.58 | 4.57 | 1.64 | 5.59 | 0.001 | 2.11 |

| ODSIS | 8.43 | 2.77 | 3.71 | 1.71 | 3.31 | 0.016 | 1.25 |

| PANAS | |||||||

| Positive Affect | 17.43 | 2.86 | 29.00 | 4.23 | 5.28 | 0.002 | 2.00 |

| Negative Affect | 29.71 | 2.49 | 17.57 | 3.19 | 4.89 | 0.003 | 1.85 |

| WSAS | 17.43 | 3.53 | 15.57 | 5.17 | 0.74 | 0.486 | 0.28 |

| QLI | 4.60 | 0.85 | 6.64 | 0.62 | 5.38 | 0.002 | 2.03 |

| PTGI | 35.43 | 8.84 | 53.14 | 12.24 | 3.24 | 0.018 | 1.22 |

| PIL-10 | 43.57 | 4.36 | 55.29 | 3.81 | 3.31 | 0.016 | 1.25 |

| FFMQ-15 | |||||||

| Observe | 2.81 | 0.50 | 3.29 | 0.43 | 1.31 | 0.237 | 0.50 |

| Describe | 3.57 | 0.37 | 3.67 | 0.39 | 0.26 | 0.805 | 0.10 |

| Awareness | 3.57 | 0.35 | 3.86 | 0.28 | 1.00 | 0.356 | 0.38 |

| No judgment | 3.62 | 0.41 | 3.52 | 0.39 | −0.79 | 0.457 | −0.30 |

| No reactivity | 2.76 | 0.21 | 2.57 | 0.25 | −0.60 | 0.569 | −0.23 |

| SCS-SF | |||||||

| Self-compassion | 2.75 | 0.33 | 3.03 | 0.41 | 1.71 | 0.139 | 0.64 |

| Common humanity | 2.82 | 0.21 | 3.28 | 0.36 | 1.45 | 0.197 | 0.55 |

| Mindfulness | 2.64 | 0.25 | 3.04 | 0.31 | 1.39 | 0.214 | 0.52 |

References

- Acierno, R., Kauffman, B., Muzzy, W., Tejada, M. H., & Lejuez, C. (2021). Behavioral activation and therapeutic exposure vs. cognitive therapy for grief among combat veterans: A randomized clinical trial of bereavement interventions. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 38(12), 1470–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, G. (2009). Using the Internet to provide cognitive behaviour therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(3), 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, G., Carlbring, P., & Hadjistavropoulos, H. D. (2017). Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy. In The science of cognitive behavioral therapy (pp. 531–549). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, G., Cuijpers, P., Carlbring, P., Riper, H., & Hedman, E. (2014). Guided Internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry, 13, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, G., Cuijpers, P., Craske, M. G., McEvoy, P., & Titov, N. (2010). Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 5(10), e13196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio-Martínez, Á., Masluk, B., Montero-Marin, J., Olivan-Blázquez, B., Navarro-Gil, M. T., García-Campayo, J., & Magallón-Botaya, R. (2019). Validation of five facets mindfulness questionnaire—Short form, in Spanish, general health care services patients sample: Prediction of depression through mindfulness scale. PLoS ONE, 14(4), e0214503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Beck depression inventory-second edition (BDI-II). Psychological Corporation. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft00742-000 (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Bentley, K. H., Gallagher, M. W., Carl, J. R., & Barlow, D. H. (2014). Development and validation of the overall depression severity and impairment scale. Psychological Assessment, 26(3), 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergman, A. S., Axberg, U., & Hanson, E. (2017). When a parent dies—A systematic review of the effects of support programs for parentally bereaved children and their caregivers. BMC Palliative Care, 16(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boelen, P. A., de Keijser, J., van den Hout, M. A., & van den Bout, J. (2007). Treatment of complicated grief: A comparison between cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counseling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(2), 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelen, P. A., & Smid, G. E. (2017). Disturbed grief: Prolonged grief disorder and persistent complex bereavement disorder. BMJ, 357, j2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkovec, T. D., & Nau, S. D. (1972). Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 3(4), 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borson, S., Korpak, A., Carbajal-Madrid, P., Likar, D., Brown, G. A., & Batra, R. (2019). Reducing barriers to mental health care: Bringing evidence-based psychotherapy home. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(10), 2174–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella, C., Mira, A., Moragrega, I., García-Palacios, A., Bretón-López, J., Castilla, D., Riera López del Amo, A., Soler, C., Molinari, G., Quero, S., Guillén-Botella, V., Miralles, I., Nebot, S., Serrano, B., Majoe, D., Alcañiz, M., & Baños, R. M. (2016). An Internet-based program for depression using activity and physiological sensors: Efficacy, expectations, satisfaction, and ease of use. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella, C., Osma, J., Palacios, A. G., Guillen, V., & Banos, R. (2008). Treatment of complicated grief using virtual reality: A case report. Death Studies, 32(7), 674–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenes, G. A., Munger, H. M., Miller, M. E., Divers, J., Anderson, A., Hargis, G., & Danhauer, S. C. (2021). Predictors of preference for cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and yoga interventions among older adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 138, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodbeck, J., Berger, T., Biesold, N., Rockstroh, F., & Znoj, H. J. (2019). Evaluation of a guided internet-based self-help intervention for older adults after spousal bereavement or separation/divorce: A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 252, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, H. G., Cairns, P., Emechebe, N., Hernandez, D. F., Mason, T. M., Bell, J., Kip, K. E., Barrison, P., & Tofthagen, C. (2020). Accelerated resolution therapy: Randomized controlled trial of a complicated grief intervention. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 37(10), 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, E., Mauro, C., Robinaugh, D. J., Skritskaya, N. A., Wang, Y., Gribbin, C., Ghesquiere, A., Horenstein, A., Duan, N., Reynolds, C., Zisook, S., Simon, N. M., & Katherine, M. (2015). The structured clinical interview for complicated grief: Reliability, validity, and exploratory factor analysis. Depress Anxiety, 32(7), 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell-Sills, L., Norman, S. B., Craske, M. G., Sullivan, G., Lang, A. J., Chavira, D. A., Bystritsky, A., Sherbourne, C., Roy-Byrne, P., & Stein, M. B. (2009). Validation of a brief measure of anxiety-related severity and impairment: The Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS). Journal of Affective Disorders, 112(1–3), 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, D., Mira, A., Bretón-López, J., Castilla, D., Botella, C., Baños, R. M., & Quero, S. (2018). The acceptability of an internet-based exposure treatment for flying phobia with and without therapist guidance: Patients’ expectations, satisfaction, treatment preferences, and usability. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 14, 879–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, D., Navarro-Gil, M., Herrera-Mercadal, P., Martínez-García, L., Cebolla, A., Borao, L., López-Del-Hoyo, Y., Castilla, D., del Río, E., García-Campayo, J., & Quero, S. (2019). Feasibility of Internet Attachment-Based Compassion Therapy (iABCT) in the general population: Study protocol (Preprint). JMIR Research Protocols, 9, e16717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlbring, P., Andersson, G., Cuijpers, P., Riper, H., & Hedman-Lagerlöf, E. (2018). Internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 47(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla, D., Garcia-Palacios, A., Miralles, I., Breton-Lopez, J., Parra, E., Rodriguez-Berges, S., & Botella, C. (2016). Effect of Web navigation style in elderly users. Computers in Human Behavior, 1(55), 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, D., Sweeny, K., Sheehan, P., Rasmussen, B., Smit, F., Cuijpers, P., & Saxena, S. (2016). Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: A global return on investment analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(5), 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, A. Y., Caserta, M., Lund, D., Suen, M. H., Xiu, D., Chan, I. K., & Chu, K. S. (2019). Dual-process bereavement group intervention (DPBGI) for widowed older adults. The Gerontologist, 59(5), 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H., Griffiths, K. M., & Farrer, L. (2009). Adherence in internet interventions for anxiety and depression. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 11(2), e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (L. E. Associates, Ed.; 2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers, P., Van Straten, A., & Andersson, G. (2008). Internet-administered cognitive behavior therapy for health problems: A systematic review. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 31(2), 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J., Shevlin, M., Cerda, C., & McElroy, E. (2025). ICD-11 prolonged grief disorder, physical health, and somatic problems: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology in Europe, 7(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delevry, D., & Le, Q. A. (2019). Effect of treatment preference in randomized controlled trials: Systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Patient, 12(6), 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nardo, P. A., Barlow, D. H., & Brown, T. A. (1994). Anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: Lifetime version (ADIS-IV-L). Graywind Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Diolaiuti, F., Marazziti, D., Beatino, M. F., Mucci, F., & Pozza, A. (2021). Impact and consequences of COVID-19 pandemic on complicated grief and persistent complex bereavement disorder. Psychiatry Research, 300, 113916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-García, A., González-Robles, A., Mor, S., Mira, A., Quero, S., García-Palacios, A., Baños, R. M., & Botella, C. (2020). Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Psychometric properties of the online Spanish version in a clinical sample with emotional disorders. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez-Rodriguez, A., Sanz-Gomez, S., González Ramírez, L. P., Herdoiza-Arroyo, P. E., Trevino Garcia, L. E., de la Rosa-Gómez, A., González-Cantero, J. O., Macias-Aguinaga, V., & Miaja, M. (2023). The efficacy and usability of an unguided web-based grief intervention for adults who lost a loved one during the COVID-19 pandemic: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, e43839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donker, T., Blankers, M., Hedman, E., Ljotsson, B., Petrie, K., & Christensen, H. (2015). Economic evaluations of Internet interventions for mental health: A systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 45(16), 3357–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echezarraga, A., Calvete, E., & Hayas, C. L. (2019). Validation of the Spanish version of the work and social adjustment scale in a sample of individuals with bipolar disorder. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 57(5), 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisma, M. C., Boelen, P. A., & Lenferink, L. I. M. (2020). Prolonged grief disorder following the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Psychiatry Research, 288, 113031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisma, M. C., Boelen, P. A., van den Bout, J., Stroebe, W., Schut, H. A. W., Lancee, J., & Stroebe, M. S. (2015). Internet-based exposure and behavioral activation for complicated grief and rumination: A randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 46(6), 729–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisma, M. C., & Stroebe, M. S. (2021). Emotion regulatory strategies in complicated grief: A systematic review. Behavior Therapy, 52(1), 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldridge, S. M., Chan, C. L., Campbell, M. J., Bond, C. M., Hopewell, S., Thabane, L., Lancaster, G. A., Altman, D., Bretz, F., Campbell, M., Cobo, E., Craig, P., Davidson, P., Groves, T., Gumedze, F., Hewison, J., Hirst, A., Hoddinott, P., Lamb, S. E., … Tugwell, P. (2016). CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. The BMJ, 355, i5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevan, P., De Miguel, C., Prigerson, H. G., García García, J. Á., Del Cura, I., Múgica, B., Martín, E., Álvarez, R., Riestra, A., Gutiérrez, A., Sanz, L., Vicente, F., García, G., Mace, I., García, F. J., Cristóbal, R., Corral, A., Bonivento, V., Guechoum, J. A., … Morán, C. (2019). Adaptación transcultural y validación del cuestionario PG-13 para la detección precoz de duelo prolongado. Medicina Paliativa, 26(1), 22–35. Available online: https://www.medicinapaliativa.es/FicherosRev/248/2/06_OR_Estevan_MEDPAL.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Eysenbach, G., & CONSORT-EHEALTH Group. (2011). CONSORT-EHEALTH: Improving and standardizing evaluation reports of Web-based and mobile health interventions. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13(4), e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finucane, A., Canny, A., Mair, A. P. A., Harrop, E., Selman, L. E., Swash, B., Wakefield, D., & Gillanders, D. (2024). A rapid review of the evidence for online interventions for bereavement support. Palliative Medicine, 39, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Campayo, J., Navarro-Gil, M., Andrés, E., Montero-Marin, J., López-Artal, L., & Demarzo, M. M. P. (2014). Validation of the Spanish versions of the long (26 items) and short (12 items) forms of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS). Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 12(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Alandete, J. (2014). Análisis factorial de una versión española de Purpose-In-Life Test, en función del género y edad. Pensamiento Psicológico, 12(1), 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Campayo, J. (2018). Mindfulness: Nuevo manual práctico: El camino de la atención plena (J. García-Campayo, Ed.). Siglantana. [Google Scholar]

- García-Campayo, J. (2019). La práctica de la compasión: Amabilidad con los demás y con uno mismo. ILUS BOOKS Siglantana. Available online: https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=6Wo3EQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT3&dq=La+pr%C3%A1ctica+de+la+compasi%C3%B3n:+Amabilidad+con+los+dem%C3%A1s+y+con+uno+mismo.+ILUS+BOOKS+Siglantana.&ots=8FWmG1MTEe&sig=C2DA5LS-G9fSTZrG2prQ5Xwhrw4&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=La%20pr%C3%A1ctica%20de%20la%20compasi%C3%B3n%3A%20Amabilidad%20con%20los%20dem%C3%A1s%20y%20con%20uno%20mismo.%20ILUS%20BOOKS%20Siglantana.&f=false (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- García-Campayo, J., Campos, D., Herrera-Mercadal, P., Navarro-Gil, M., Ziemer, K., Palma, B., Mostoufi, S., & Aristegui, R. (2023). The attachment-based compassion therapy: A manual for self-application. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Campayo, J., Navarro-Gil, M., & Demarzo, M. (2016). Attachment-based compassion therapy. Mindfulness & Compassion, 1(2), 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasgow, R. E., Nelson, C. C., Kearney, K. A., Reid, R., Ritzwoller, D. P., Strecher, V. J., Couper, M. P., Green, B., & Wildenhaus, K. (2007). Reach, engagement, and retention in an internet-based weight loss program in a multi-site randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 9(2), e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Robles, A., Mira, A., Miguel, C., Molinari, G., Díaz-García, A., García-Palacios, A., Bretón-López, J. M., Quero, S., Baños, R. M., & Botella, C. (2018). A brief online transdiagnostic measure: Psychometric properties of the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS) among Spanish patients with emotional disorders. PLoS ONE, 13(11), e0206516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, F., Lindenmeyer, A., Powell, J., Lowe, P., & Thorogood, M. (2006). Why are health care interventions delivered over the internet? A systematic review of the published literature. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 8(2), e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, K. M., & Christensen, H. (2007). Internet-based mental health programs: A powerful tool in the rural medical kit. The Australian Journal of Rural Health, 15(2), 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D. (2021). Compassion-focused grief therapy. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 49(6), 780–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrsen, K., Tølbøll, M. M., & Larsen, L. H. (2024). Effects of an integrated treatment program on grief and distress among parentally bereaved young adults. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 89(1), 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A., & Gumport, N. (2015). Evidence-based psychological treatments for mental disorders: Modifiable barriers to access and possible solutions. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 68, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedman, E., Furmark, T., Carlbring, P., Ljótsson, B., Rück, C., Lindefors, N., & Andersson, G. (2011). A 5-Year follow-up of internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13(2), e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedman-Lagerlöf, E., Carlbring, P., Svärdman, F., Riper, H., Cuijpers, P., & Andersson, G. (2023). Therapist-supported Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy yields similar effects as face-to-face therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry, 22(2), 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, R., Große, J., Nagl, M., Niederwieser, D., Mehnert, A., & Kersting, A. (2018). Internet-based grief therapy for bereaved individuals after loss due to Haematological cancer: Study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 18, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, A. O., & Greenberg, L. S. (1989). Development and validation of the working alliance inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36(2), 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannsen, M., Damholdt, M. F., Zachariae, R., Lundorff, M., Farver-Vestergaard, I., & O’Connor, M. (2019). Psychological interventions for grief in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Affective Disorders, 253, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, O., Michel, T., Andersson, G., & Paxling, B. (2015). Experiences of non-adherence to Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy: A qualitative study. Internet Interventions, 2(2), 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A. H., & Litz, B. T. (2014). Prolonged grief disorder: Diagnostic, assessment, and treatment considerations. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 45(3), 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, J., Nagl, M., Hoffmann, R., Linde, K., & Kersting, A. (2022). Therapist-assisted web-based intervention for prolonged grief disorder after cancer bereavement: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mental Health, 9(2), e27642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karyotaki, E., Ebert, D. D., Donkin, L., Riper, H., Twisk, J., Burger, S., Rozental, A., Lange, A., Williams, A. D., Zarski, A. C., Geraedts, A., van Straten, A., Kleiboer, A., Meyer, B., Ünlü Ince, B. B., Buntrock, C., Lehr, D., Snoek, F. J., Andrews, G., … Cuijpers, P. (2018). Do guided internet-based interventions result in clinically relevant changes for patients with depression? An individual participant data meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 63, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersting, A., Dölemeyer, R., Steinig, J., Walter, F., Kroker, K., Baust, K., & Wagner, B. (2013). Brief internet-based intervention reduces posttraumatic stress and prolonged grief in parents after the loss of a child during pregnancy: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 82(6), 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R. C., Demler, O., Frank, R. G., Olfson, M., Pincus, H. A., Walters, E. E., Wang, P., Wells, K. B., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2005). Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. The New England Journal of Medicine, 352(24), 2515–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killikelly, C., Smith, K. V., Zhou, N., Prigerson, H. G., O’Connor, M. F., Kokou-Kpolou, C. K., Boelen, P. A., & Maercker, A. (2025). Prolonged grief disorder. The Lancet, 405(10489), 1621–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokou-Kpolou, C. K., Fernández-Alcántara, M., & Cénat, J. M. (2020). Prolonged grief related to COVID-19 deaths: Do we have to fear a steep rise in traumatic and disenfranchised griefs? Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(c), S94–S95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komariah, M., Amirah, S., Faisal, E., Prayogo, S., Maulana, S., Platini, H., Suryani, S., Yosep, I., & Arifin, H. (2022). Efficacy of internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for depression and anxiety among global population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a randomized controlled trial study. Healthcare, 10(7), 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacasta, M. A., & Cruzado, J. A. (2023). Effectiveness of a cognitive–behavioral group therapy for complicated grief in relatives of patients with cancer: A randomized clinical trial. Palliative & Supportive Care, 22, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenferink, L. I., Eisma, M. C., Buiter, M. Y., de Keijser, J., & Boelen, P. A. (2023). Online cognitive behavioral therapy for prolonged grief after traumatic loss: A randomized waitlist-controlled trial. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 52(5), 508–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limonero, J., Lacasta Reverte, M., Garcia Garcia, J., Mate Mendez, J., & Prigerson, H. (2009). Adaptación al castellano del inventario de duelo complicado. Medicina Paliativa, 16(5), 291–297. [Google Scholar]

- Litz, B. T., Schorr, Y., Delaney, E., Au, T., Papa, A., Fox, A. B., Morris, S., Nickerson, A., Block, S., & Prigerson, H. G. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of an internet-based therapist-assisted indicated preventive intervention for prolonged grief disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 61, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Montoyo, A., Quero, S., Montero-Marin, J., Barcelo-Soler, A., Beltran, M., Campos, D., & Garcia-Campayo, J. (2019). Effectiveness of a brief psychological mindfulness-based intervention for the treatment of depression in primary care: Study protocol for a randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Lara, E., Garrido-Cumbrera, M., & Díaz-Cuevas, M. P. (2012). Improving territorial accessibility of mental health services: The case of Spain. The European Journal of Psychiatry, 26(4), 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lundorff, M., Holmgren, H., Zachariae, R., Farver-Vestergaard, I., & O’Connor, M. (2017). Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in adult bereavement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 212, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGoron, L., Ratner, H. H., Knoff, K. A. G., Hvizdos, E., & Ondersma, S. J. (2019). A pragmatic internet intervention to promote positive parenting and school readiness in early childhood: Initial evidence of program use and satisfaction. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting, 2(2), e14518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzich, J. E., Ruipérez, M. A., Pérez, C., Yoon, G., Liu, J., & Mahmud, S. (2000). The Spanish version of the quality of life index: Presentation and validation. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 188(5), 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, A., González-Robles, A., Molinari, G., Miguel, C., Díaz-García, A., Bretón-López, J., García-Palacios, A., Quero, S., Baños, R., & Botella, C. (2019). Capturing the severity and impairment associated with depression: The overall depression Severity and Impairment Scale (ODSIS) validation in a Spanish clinical sample. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 2717–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, S., Botella, C., Campos, D., Carlbring, P., Tur, C., & Quero, S. (2022). An internet-based treatment for flying phobia using 360° images: A feasibility pilot study. Internet Interventions, 28, 100510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundt, J. C., Marks, I. M., Shear, M. K., & Greist, J. H. (2002). The work and social adjustment scale: A simple measure of impairment in functioning. British Journal of Psychiatry, 180, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musiat, P., & Tarrier, N. (2014). Collateral outcomes in e-mental health: A systematic review of the evidence for added benefits of computerized cognitive behavior therapy interventions for mental health. Psychological Medicine, 44, 3137–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Gil, M., Lopez-del-Hoyo, Y., Modrego-Alarcón, M., Montero-Marin, J., Van Gordon, W., Shonin, E., & Garcia-Campayo, J. (2020). Effects of Attachment-Based Compassion Therapy (ABCT) on self-compassion and attachment style in healthy people. Mindfulness, 11(1), 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R. A. (2000). Searching for the meaning of meaning: Grief therapy and the process of reconstruction. Death Studies, 24(6), 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R. A. (2001). Meaning reconstruction & the experience of loss. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Norcross, J., & Lambert, M. (2018). Psychotherapy relationships that work III. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacios, J. E., Richards, D., Palmer, R., Coudray, C., Hofmann, S. G., Palmieri, P. A., & Frazier, P. (2018). Supported internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy programs for depression, anxiety, and stress in university students: Open, Non-randomised trial of acceptability, efficacy, and satisfaction. JMIR Mental Health, 5(4), e11467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prigerson, H. G., Maciejewski, P. K., Reynolds, C. F., Bierhals, A. J., Newsom, J. T., Fasiczka, A., Frank, E., Doman, J., & Miller, M. (1995). Inventory of complicated grief: A scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Research, 59(1–2), 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachyla, I., Mor, S., Cuijpers, P., Botella, C., Castilla, D., & Quero, S. (2020). A guided Internet-delivered intervention for adjustment disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 28, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, F., Pommier, E., Neff, K. D., & Van Gucht, D. (2011). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 18(3), 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raue, P., Schulberg, H., Heo, M., Klimstra, S., & Bruce, M. (2009). Patients’ depression treatment preferences and initiation, adherence, and outcome: A randomized primary care study. Psychiatric Services, 60(3), 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitsma, L., Boelen, P. A., de Keijser, J., & Lenferink, L. I. M. (2023). Self-guided online treatment of disturbed grief, posttraumatic stress, and depression in adults bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic: A randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 163, 104286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D., Murphy, T., Viganó, N., Timulak, L., Doherty, G., Sharry, J., & Hayes, C. (2016). Acceptability, satisfaction and perceived efficacy of “Space from Depression” an internet-delivered treatment for depression. Internet Interventions, 5, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohrbach, P. J., Dingemans, A. E., Evers, C., Van Furth, E. F., Spinhoven, P., Aardoom, J. J., Lähde, I., Clemens, F. C., & Van den Akker-Van Marle, M. E. (2023). Cost-effectiveness of internet interventions compared with treatment as usual for people with mental disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, e38204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, D. C. M., Knaevelsrud, C., Duran, G., Waadt, S., & Goldbeck, L. (2014). Internet-based psychotherapy in young adult survivors of pediatric cancer: Feasibility and participants’ satisfaction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 17(9), 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shear, K. (2015a). Complicated grief. The New England Journal of Medicine, 372(2), 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shear, K. (2015b). Complicated grief treatment. In Bereavement care. Columbia Center of Complicated Grief. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shear, K., Reynolds, C. F., Simon, N. M., Zisook, S., Wang, Y., Mauro, C., Duan, N., Lebowitz, B., & Skritskaya, N. (2016). Optimizing treatment of complicated grief a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(7), 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skritskaya, N. A., Mauro, C., Olonoff, M., Qiu, X., Duncan, S., Wang, Y., Duan, N., Lebowitz, B., Reynolds, C. F., Simon, N. M., Zisook, S., & Shear, M. K. (2017). Measuring maladaptive cognitions in complicated grief: Introducing the typical beliefs questionnaire. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(5), 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spek, V., Cuijpers, P., NykIíček, I., Riper, H., Keyzer, J., & Pop, V. (2007). Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety: A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 37(3), 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroebe, M., Schut, H., & Boerner, K. (2017). Cautioning health-care professionals: Bereaved persons are misguided through the stages of grief. Omega—Journal of Death and Dying, 74(4), 455–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S., & Xiang, Z. (2021). Who suffered most after deaths due to COVID-19? Prevalence and correlates of prolonged grief disorder in COVID-19 related bereaved adults. Globalization and Health, 17(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabane, L., Mbuagbaw, L., Zhang, S., Samaan, Z., Marcucci, M., Ye, C., Thabane, M., Giangregorio, L., Dennis, B., Kosa, D., Debono, V. B., Dillenburg, R., Fruci, V., Bawor, M., Lee, J., Wells, G., & Goldsmith, C. H. (2013). A tutorial on sensitivity analyses in clinical trials: The what, why, when and how. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treml, J., Nagl, M., Linde, K., Kündiger, C., Peterhänsel, C., & Kersting, A. (2021). Efficacy of an Internet-based cognitive-behavioural grief therapy for people bereaved by suicide: A randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1926650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tur, C., Campos, D., Herrero, R., Mor, S., López-Montoyo, A., Castilla, D., & Quero, S. (2021). Internet-delivered cognitive—Behavioral Therapy (iCBT) for adults with Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD): A study protocol for a randomized feasibility trial. BMJ Open, 11, e046477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tur, C., Campos, D., & Quero, S. (2019). Internet-based psychologycal treatments for grief: Review of literature. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, XXVIII, 884–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tur, C., Campos, D., Suso-Ribera, C., Kazlauskas, E., Castilla, D., Zaragoza, I., García-Palacios, A., & Quero, S. (2022). An Internet-delivered Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (iCBT) for Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) in adults: A multiple-baseline single-case experimental design study. Internet Interventions, 29, 100558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Ballegooijen, W., Cuijpers, P., Van Straten, A., Karyotaki, E., Andersson, G., Smit, J. H., & Riper, H. (2014). Adherence to internet-based and face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy for depression: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 9(7), e0100674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Houwen, K., Schut, H., van den Bout, J., Stroebe, M., & Stroebe, W. (2010). The efficacy of a brief internet-based self-help intervention for the bereaved. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(5), 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viel, J. F., Pobel, D., & Carré, A. (1995). Incidence of leukaemia in young people around the La Hague nuclear waste reprocessing plant: A sensitivity analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 14(21–22), 2459–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, B., Grafiadeli, R., Schäfer, T., & Hofmann, L. (2022). Efficacy of an online-group intervention after suicide bereavement: A randomized controlled trial. Internet Interventions, 28, 100542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, B., Knaevelsrud, C., & Maercker, A. (2006). Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for complicated grief: A randomized controlled trial. Death Studies, 30(5), 429–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, B., & Maercker, A. (2007). A 1.5-year follow-up of an Internet-based intervention for complicated grief. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(4), 625–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, B., Rosenberg, N., Hofmann, L., & Maass, U. (2020). Web-based bereavement care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Lin, Y., Chen, J., Wang, C., Hu, R., & Wu, Y. (2020). Effects of Internet-based psycho-educational interventions on mental health and quality of life among cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 28(6), 2541–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, T., & Berger, R. (2006). Reliability and validity of a spanish version of the posttraumatic growth inventory. Research on Social Work Practice, 16(2), 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenn, J. A., O’Connor, M., Kane, R. T., Rees, C. S., & Breen, L. J. (2019). A pilot randomised controlled trial of metacognitive therapy for prolonged grief. BMJ Open, 9(1), e021409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, L. C. (2007). Methodological and ethical issues in Internet-mediated research in the field of health: An integrated review of the literature. Social Science and Medicine, 65(4), 782–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. L., Hardt, M. M., Henschel, A. V., & Eddinger, J. R. (2019). Experiential avoidance moderates the association between motivational sensitivity and prolonged grief but not posttraumatic stress symptoms. Psychiatry Research, 273, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittouck, C., Van Autreve, S., De Jaegere, E., Portzky, G., & van Heeringen, K. (2011). The prevention and treatment of complicated grief: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(1), 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2018). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th ed.). World Health Organization. Available online: https://icd.who.int/en (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Xiong, J., Wen, J., Pei, G., Han, X., & He, D. (2022). Effectiveness of Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for employees with depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics: JOSE, 29, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuelke, A. E., Luppa, M., Löbner, M., Pabst, A., Schlapke, C., Stein, J., & Riedel-Heller, S. G. (2021). Effectiveness and feasibility of internet-based interventions for grief after bereavement: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mental Health, 8(12), e29661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (N = 31) | GROw (N = 16) | Videoconferencing (N = 15) | Between-Group Comparison | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | χ2(1) = 2.28, p = 0.131 | |||

| Female | 29 (93.5%) | 16 (100%) | 13 (86.7%) | |

| Male | 2 (6.5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Age mean (SD) | 39.1 (12.6) | 37.6 (12.2) | 40.7 (13.2) | F (1,29) = 0.465, p= 0.501 |

| Educational level | χ2(2) = 2.36, p = 0.307 | |||

| Primary education | 2 (6.5%) | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Secondary education | 12 (38.7%) | 5(31.3%) | 7 (46.7%) | |

| Higher education | 17 (54.8%) | 9 (56.3%) | 8 (53.3%) | |

| Relationship with the deceased | χ2(5) = 3.23, p = 0.665 | |||

| Grandfather/grandmother | 5 (16.1%) | 3 (18.8%) | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Father/mother | 17 (54.8%) | 9 (56.3%) | 8 (53.3%) | |

| Brother/sister | 4 (12.9%) | 2 (12.5%) | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Partner | 2 (6.5%) | 1 (6.3%) | 1 (6.7%) | |

| Son/daughter | 2 (6.5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Uncle/aunt | 1 (3.2%) | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Time since loss | χ2(3) = 1.37, p = 0.713 | |||

| >6 months | 9 (29%) | 6 (37.5%) | 3 (20%) | |

| 12–24 months | 10 (32.3%) | 5 (31.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | |

| 24–48 months | 2 (6.5%) | 1 (6.3%) | 1 (6.7%) | |

| >24 months | 10 (32.3%) | 4 (25%) | 6 (40%) | |

| Type of death | χ2(3) = 2.00, p = 0.571 | |||

| Illness | 27 (87.1%) | 14 (87.5%) | 13 (86.7%) | |

| Natural death | 1 (3.2%) | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Suicide | 2 (6.5%) | 1 (6.3%) | 1 (6.7%) | |

| Accident | 1 (3.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (6.7%) |

| N | Module Access Mean (SD) | Reviews Mean (SD) | Time (Min) Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Module 1 | 13 | 2.2 (1.7) | 0.92 (1.0) | 340.8 (104) |

| Module 2 | 13 | 2.6 (3.9) | 0.54 (1.0) | 358.2 (126.4) |

| Module 3 | 13 | 3.1 (5.5) | 0.46 (1.0) | 364.3 (207.3) |

| Module 4 | 11 | 8.7 (9.9) | 0.45 (0.9) | 351.3 (141.8) |

| Module 5 | 9 | 2.7 (4.0) | 0.11 (0.3) | 317.2 (157.4) |

| Module 6 | 8 | 7.4 (10.1) | 0.13 (0.4) | 321.6 (186.5) |

| Module 7 | 8 | 3.9 (6.0) | 0.25 (0.7) | 568.8 (276.2) |

| Module 8 | 8 | 1.6 (2.1) | 0.13 (0.4) | 374.3 (197.3) |

| Before Treatment (n = 30) | After Treatment (n = 16) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GROw (n = 16) | Videoconferencing (n = 14) | GROw (n = 5) | Videoconferencing (n = 11) | |

| Preference | ||||

| GROw | 7 (41.2%) | 5 (35.7%) | 4 (80%) | 1 (9.1%) |

| Videoconferencing | 9 (52.9%) | 9 (64.3%) | 1 (20%) | 10 (90.9%) |

| Subjective efficacy | ||||

| GROw | 3 (17.6%) | 4 (28.6%) | 4 (80%) | 0 (0%) |

| Videoconferencing | 13 (76.5%) | 10 (71.4%) | 1 (20%) | 11 (100%) |

| Logic | ||||

| GROw | 2 (11.8%) | 2 (14.3%) | 1 (20%) | 0 (0%) |

| Videoconferencing | 14 (82.4%) | 12 (85.7%) | 4 (80%) | 11 (100%) |

| Subjective aversiveness | ||||

| GROw | 4 (23.5%) | 6 (42.9%) | 5 (100%) | 4 (36.4%) |

| Videoconferencing | 12 (70.6%) | 8 (57.1%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (63.3%) |

| Recommendation | ||||

| GROw | 4 (23.5%) | 4 (28.6%) | 5 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Videoconferencing | 12 (70.6%) | 10 (71.4%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (100%) |

| GROw | Videoconferencing | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment Expectations M (SD) (n = 14) | Post-Treatment Satisfaction M (SD) (n = 5) | Pretreatment Expectations M (SD) (n = 14) | Post-Treatment Satisfaction M (SD) (n = 11) | |

| Intervention logic | 7.7 (1.7) | 9.4 (0.9) | 9.1 (1.0) | 9.2 (1.1) |

| Treatment satisfaction | 8.6 (1.6) | 9 (1) | 9.1 (1.5) | 8.8 (1.2) |

| Treatment recommendation | 9.4 (0.9) | 10 (0) | 9.3 (1.2) | 9.5 (0.8) |

| Usefulness for treating other problems | 8.1 (1.8) | 9 (1) | 9.3 (0.9) | 7.9 (1.8) |

| Personal usefulness | 8.1(1.8) | 9 (0.7) | 9.1 (1.2) | 8.6 (1.1) |

| Aversiveness | 5.3 (3.5) | 3 (4.1) | 4.8 (3.4) | 5.1 (3.7) |

| GROw (n = 4) M (SD) | Videoconferencing (n = 10) M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Usefulness of motivation to change | 8.25 (1.26) | 7.9 (1.91) |

| Usefulness of psychoeducation | 8.25 (1.71) | 8.5 (1.35) |

| Usefulness of behavioral activation | 8.50 (1.29) | 8.3 (1.16) |

| Usefulness of experiential exposure | 9.50 (0.58) | 8.4 (1.84) |

| Usefulness of mindfulness | 8.25 (0.50) | 8.1 (1.73) |

| Usefulness of compassion strategies | 7.50 (1.73) | 8.6 (1.08) |

| Usefulness of writing assignments | 9.50 (0.58) | 8.9 (1.2) |

| Usefulness of cognitive reappraisal | 9.25 (0.96) | 8.8 (1.4) |

| Usefulness of relapse prevention | 8.25 (1.5) | 8.5 (1.08) |

| Usefulness of images | 8.50 (1.73) | - |

| Usefulness of videos | 8.75 (0.96) | - |

| Usefulness of audios | 8.75 (0.96) | - |

| Usefulness of written information | 9 (0.82) | - |

| Satisfaction with the weekly follow-up phone calls | 9.50 (1) | - |

| Usefulness of weekly follow-up phone calls | 9 (1.4) | - |

| Usefulness for adherence of weekly follow-up phone calls | 9 (2) | - |

| Outcome | Pre | Post | F | df1 | df2 | p | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | ||||||

| IGC | 41.43 | 3.98 | 31.98 | 4.18 | 12.23 | 1 | 7.67 | 0.009 | 1.26 |

| BDI-II | 28.86 | 2.78 | 15.45 | 3.07 | 20.69 | 1 | 9.43 | 0.001 | 1.48 |

| TBQ | 64.03 | 3.72 | 47.98 | 3.97 | 28.51 | 1 | 8.38 | <0.001 | 1.84 |

| OASIS | 10.39 | 1.16 | 6.66 | 1.24 | 16.23 | 1 | 8.55 | 0.003 | 1.38 |

| ODSIS | 9.65 | 1.23 | 6.99 | 1.36 | 4.22 | 1 | 8.76 | 0.071 | 0.69 |

| PANAS | |||||||||

| Positive Affect | 18.10 | 1.58 | 22.63 | 1.67 | 15.84 | 1 | 7.85 | 0.004 | 1.42 |

| Negative Affect | 27.50 | 2.25 | 21.05 | 2.52 | 6.18 | 1 | 9.90 | 0.032 | 0.79 |

| WSAS | 18.76 | 2.72 | 18.38 | 2.88 | 0.03 | 1 | 8.39 | 0.858 | 0.06 |

| QLI | 4.39 | 0.48 | 5.37 | 0.49 | 14.62 | 1 | 7.53 | 0.006 | 1.39 |

| PTGI | 35.49 | 5.68 | 48.21 | 6.16 | 6.07 | 1 | 7.69 | 0.040 | 0.89 |

| PIL-10 | 36.98 | 2.64 | 42.48 | 2.81 | 7.06 | 1 | 7.67 | 0.030 | 0.96 |

| FFMQ-15 | |||||||||

| Observe | 2.72 | 0.23 | 2.65 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 1 | 7.72 | 0.655 | −0.17 |

| Describe | 3.19 | 0.33 | 3.14 | 0.39 | 0.02 | 1 | 8.01 | 0.895 | −0.05 |

| Awareness | 2.89 | 0.24 | 3.01 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 1 | 8.95 | 0.624 | 0.17 |

| No judgment | 2.69 | 0.28 | 3.39 | 0.33 | 4.13 | 1 | 9.30 | 0.072 | 0.67 |

| No reactivity | 2.72 | 0.18 | 2.77 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 1 | 7.95 | 0.690 | 0.15 |

| SCS-SF | |||||||||

| Self-compassion | 2.37 | 0.25 | 2.76 | 0.27 | 2.78 | 1 | 8.02 | 0.134 | 0.59 |

| Common humanity | 2.77 | 0.22 | 2.97 | 0.25 | 0.54 | 1 | 8.48 | 0.483 | 0.25 |

| Mindfulness | 2.58 | 0.21 | 2.39 | 0.23 | 0.76 | 1 | 8.70 | 0.407 | −0.30 |

| Outcome | Pre | Post | F | df1 | df2 | p | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | ||||||

| IGC | 38.00 | 3.26 | 19.59 | 3.99 | 32.41 | 1 | 7.20 | <0.001 | 2.12 |

| BDI-II | 23.33 | 2.33 | 8.84 | 2.82 | 41.28 | 1 | 7.51 | <0.001 | 2.34 |

| TBQ | 56.20 | 4.73 | 37.07 | 5.55 | 22.10 | 1 | 7.20 | 0.002 | 1.75 |

| OASIS | 9.47 | 1.24 | 4.00 | 1.43 | 30.78 | 1 | 6.30 | 0.001 | 2.21 |

| ODSIS | 8.67 | 1.43 | 3.90 | 1.73 | 12.24 | 1 | 7.21 | 0.010 | 1.30 |

| PANAS | |||||||||

| Positive Affect | 19.60 | 2.07 | 30.64 | 2.53 | 28.90 | 1 | 7.71 | <0.001 | 1.94 |

| Negative Affect | 29.47 | 1.85 | 17.42 | 2.44 | 27.28 | 1 | 8.15 | <0.001 | 1.83 |

| WSAS | 16.47 | 2.56 | 14.81 | 3.06 | 0.49 | 1 | 7.43 | 0.507 | 0.26 |

| QLI | 4.77 | 0.44 | 6.78 | 0.52 | 30.31 | 1 | 6.95 | <0.001 | 2.09 |

| PTGI | 30.80 | 5.96 | 49.37 | 7.02 | 12.81 | 1 | 7.34 | 0.008 | 1.32 |

| PIL-10 | 42.87 | 2.58 | 54.87 | 3.42 | 13.60 | 1 | 8.44 | 0.006 | 1.27 |

| FFMQ-15 | |||||||||

| Observe | 2.47 | 0.29 | 3.06 | 0.37 | 3.14 | 1 | 8.08 | 0.114 | 0.62 |

| Describe | 3.42 | 0.26 | 3.59 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 1 | 8.05 | 0.645 | 0.17 |

| Awareness | 3.18 | 0.27 | 3.58 | 0.33 | 1.96 | 1 | 6.18 | 0.210 | 0.56 |

| No judgment | 3.51 | 0.27 | 3.42 | 0.28 | 0.57 | 1 | 6.18 | 0.477 | −0.30 |

| No reactivity | 2.42 | 0.17 | 2.54 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 1 | 10.35 | 0.682 | 0.13 |

| SCS-SF | |||||||||

| Self-compassion | 2.62 | 0.23 | 2.92 | 0.26 | 3.40 | 1 | 6.60 | 0.110 | 0.72 |

| Common humanity | 2.82 | 0.17 | 3.28 | 0.25 | 3.11 | 1 | 11.37 | 0.105 | 0.52 |

| Mindfulness | 2.57 | 0.17 | 3.00 | 0.24 | 3.05 | 1 | 9.75 | 0.112 | 0.56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tur, C.; Campos, D.; Díaz-Sanahuja, L.; Fernández-Buendía, S.; Grimaldos, J.; De la Coba-Cañizares, L.; Kazlauskas, E.; Quero, S. Internet-Delivered Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (iCBT) for Spanish-Speaking Adults with Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD): A Randomized Feasibility Trial. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1312. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101312

Tur C, Campos D, Díaz-Sanahuja L, Fernández-Buendía S, Grimaldos J, De la Coba-Cañizares L, Kazlauskas E, Quero S. Internet-Delivered Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (iCBT) for Spanish-Speaking Adults with Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD): A Randomized Feasibility Trial. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1312. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101312

Chicago/Turabian StyleTur, Cintia, Daniel Campos, Laura Díaz-Sanahuja, Sara Fernández-Buendía, Jorge Grimaldos, Laura De la Coba-Cañizares, Evaldas Kazlauskas, and Soledad Quero. 2025. "Internet-Delivered Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (iCBT) for Spanish-Speaking Adults with Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD): A Randomized Feasibility Trial" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1312. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101312

APA StyleTur, C., Campos, D., Díaz-Sanahuja, L., Fernández-Buendía, S., Grimaldos, J., De la Coba-Cañizares, L., Kazlauskas, E., & Quero, S. (2025). Internet-Delivered Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (iCBT) for Spanish-Speaking Adults with Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD): A Randomized Feasibility Trial. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1312. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101312