Interconnecting District and Community Partners to Improve School-Level Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

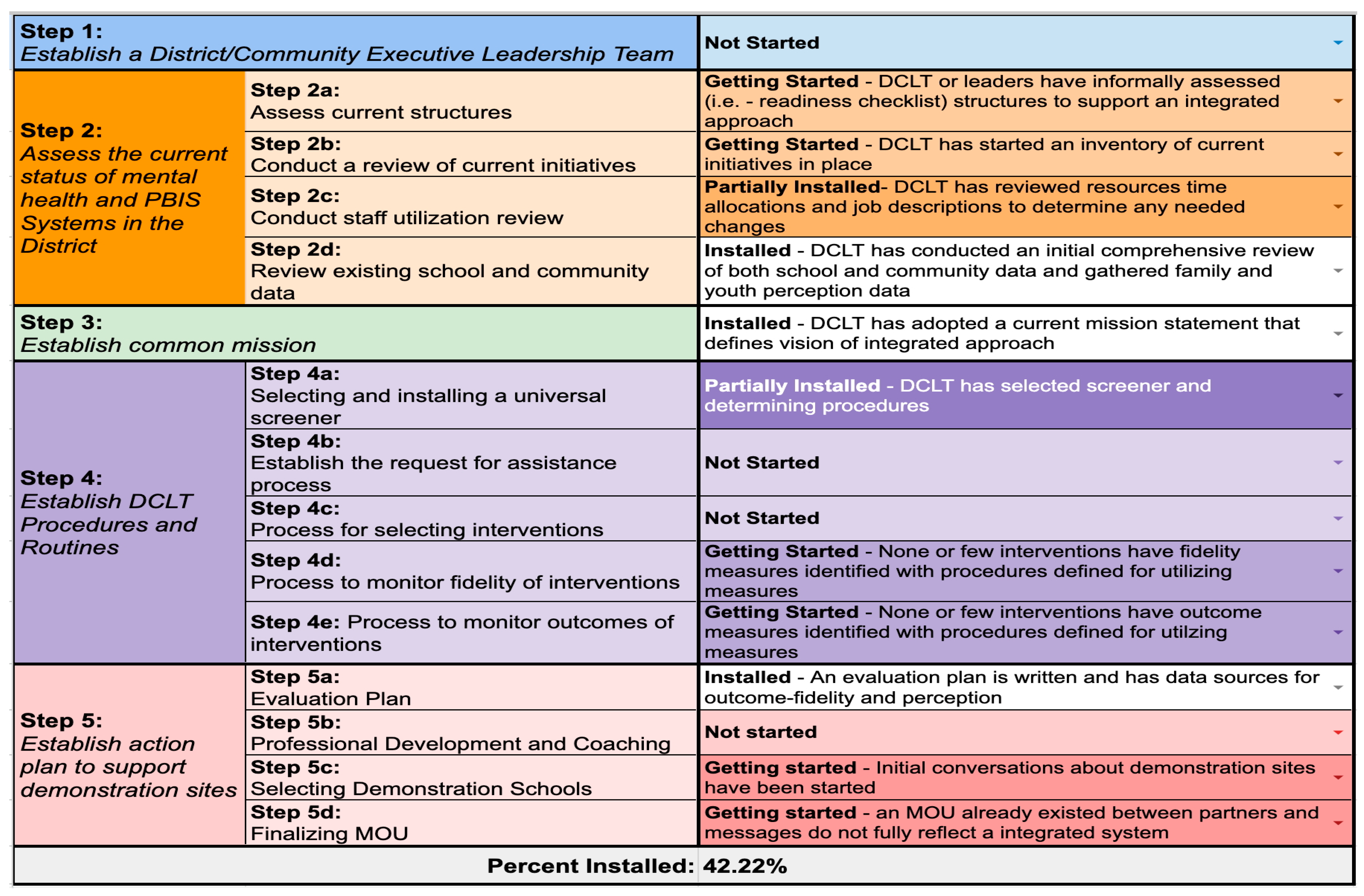

1.1. Understanding the Interconnected Systems Framework

1.2. Importance of the District Community Leadership Team in the ISF

1.3. The DCLT Installation Progress Monitoring Tool

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Procedures for Collecting Data

3. Results

3.1. Feasibility Findings

3.2. Utility Findings

- Step 5c: Selecting Demonstration Sites—highest installation average (92%)

- Step 1: Establishing a DCLT—second highest average (90%)

- Step 2c: Conduct Staff Utilization—lowest average installation (28%)

- The average range of difference between the highest and lowest installation scores per step was 24%

- ⚬

- Step-specific variances ranged from 5.66% to 46.67%

- Step 2a: Assess Current Structures—least variability (6.66%)

- Step 2c: Conduct Staff Utilization Review and 4d: Process to Monitor Fidelity of Interventions—greatest variability (46.67% and 44.44%)

- Nine of the 11 districts (82%) reaching a 70% installation rate had both Step 1: Establish DCLT and Step 3: Establish Common Mission “In Place” at the two-year benchmark

3.3. Case Study: Graves County School District

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bains, R. M., & Diallo, A. F. (2015). Mental health services in school-based health centers: A systematic review. The Journal of School Nursing, 32(1), 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, S., Eber, L., & Weist, M. (2017). Advancing education effectiveness: Interconnecting school mental health and school-wide Positive Behavior Support. Center for Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (funded by the Office of Special Education Programs, U.S. Department of Education). University of Oregon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, M. S., & Kirchner, J. (2020). Implementation science: What is it and why should I care? Psychiatry Research, 283, 112376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bommersbach, T. J., McKean, A. J., Olfson, M., & Rhee, T. G. (2023). National trends in mental health-related emergency department visits among youth, 2011–2020. JAMA, 329(17), 1469–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Youth risk behavior survey data summary & trends report: 2013–2023. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Coffey, J. H., & Horner, R. H. (2012). The sustainability of schoolwide positive behavior interventions and supports. Exceptional Children, 78(4), 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condliffe, B., Zhu, P., Doolittle, F., van Dok, M., Power, H., Denison, D., & Kurki, A. (2022). Study of training in multi-tiered systems of support for behavior: Impacts on elementary school students’ outcomes (NCEE 2022-008). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance. Available online: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Cook, C. R., Lyon, A. R., Locke, J., Waltz, T., & Powell, B. J. (2019). Adapting a compilation of implementation strategies to advance school-based implementation research and practice. Prevention Science, 20, 914–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eber, L., Barrett, S., Perales, K., Jeffrey-Pearsall, J., Pohlman, K., Putnam, R., Splett, J., & Weist, M. D. (2019). Advancing education effectiveness: Interconnecting school mental health and school-wide PBIS, volume 2: An implementation guide. Center for Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (funded by the Office of Special Education Programs, U.S. Department of Education). University of Oregon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ghandour, R. M., Sherman, L. J., Vladutiu, C. J., Ali, M. M., Lynch, S. E., Bitsko, R. H., & Blumberg, S. J. (2019). Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children. The Journal of Pediatrics, 206, 256–267.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henson, A. (2025,Personal communication.

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. (1997). 20 U.S.C. § 1414. Available online: https://sites.ed.gov/idea/statute-chapter-33/subchapter-ii/1414/d (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2024, December 31). Mental health care health professional shortage areas (HPSAs). Available online: https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/mental-health-care-health-professional-shortage-areas-hpsas/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Leeman, J., Wiecha, J. L., Vu, M., Blitstein, J. L., Allgood, S., Lee, S., & Merlo, C. (2018). School health implementation tools: A mixed methods evaluation of factors influencing their use. Implementation Science, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- March, A., Stapley, E., Hayes, D., Town, R., & Deighton, J. (2022). Barriers and facilitators to sustaining school-based mental health and wellbeing interventions: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathews, S., McIntosh, K., Frank, J. L., & May, S. L. (2014). Critical features predicting sustained implementation of school-wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 16(3), 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, K., & Turri, M. G. (2014). Positive behavior support: Sustainability and continuous regeneration. Grantee Submission. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED562561.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2022, October). School pulse panel: Staff vacancies. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/spp/results.asp (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Pas, E. T., Ryoo, J. H., Musci, R. J., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2019). A state-wide quasi-experimental effectiveness study on the scale-up of school-wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Support. Journal of School Psychology, 73, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinert, M., Fritze, D., & Nguyen, T. (2021). The state of mental health in America, 2022. Mental Health America. [Google Scholar]

- Skaar, N. (2022). Development and implementation of a rural school-based mental health system: An illustration of implementation frameworks. Research and Practices in the Schools, 9(1), 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Splett, J. W., Perales, K., Halliday-Boykins, C. A., Gilchrest, C. E., Gibson, N., & Weist, M. D. (2017). Best practices for teaming and collaboration in the interconnected systems framework. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 33(4), 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splett, J. W., Perales, K., & Weist, M. D. (2019). Interconnected systems framework—Implementation inventory (ISF-II), Version 3 [Unpublished instrument]. University of Florida.

- Sugai, G., & Horner, R. H. (2020). Sustaining and scaling Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports: Implementation drivers, outcomes, and considerations. Exceptional Children, 86(2), 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain-Bradway, J., Johnson, J., Eber, L., Barrett, S., & Weist, M. D. (2015). Interconnecting school mental health and school-wide positive behavior support. In S. Kutcher, Y. Wei, & M. D. Weist (Eds.), School mental health: Global challenges and opportunities (pp. 282–298). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weist, M. D., Lever, N., Bradshaw, C., & Owens, J. S. (2014). Further advancing the field of school mental health. In M. Weist, N. Lever, C. Bradshaw, & J. Owens (Eds.), Handbook of school mental health: Research, training, practice, and policy (2nd ed., pp. 1–16). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Weist, M. D., Splett, J. W., Halliday, C. A., Gage, N. A., Seaman, M. A., Perkins, K. A., Perales, K., Miller, E., Collins, D., & DiStefano, C. (2022). A randomized controlled trial on the interconnected systems framework for school mental health and PBIS: Focus on proximal variables and school discipline. Journal of School Psychology, 94, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ISF DCLT Installation Progress Monitoring Tool—Incremental Installation Phases | |||||

| Step 1: Establish a District/Community Executive Leadership Team | Not Started | Getting started—A team of district and/or community leaders meets but without all stakeholders represented and no plan to expand | Partially Installed—Representative DCLT is established but not meeting regularly at this time | Installed—Representative DCLT meeting routinely with operating procedures | |

| Step 2: Assess the current status of mental health and PBIS Systems in the District | Step 2a: Assess current structures | Not Started | Getting Started—DCLT or leaders have informally assessed (i.e., readiness checklist) structures to support an integrated approach | Partially Installed—DCLT has completed DSFI (or similar) and action plan that is more than a year old or not being used to guide work | Installed—DCLT has completed DSFI (or similar) and identified action steps |

| Step 2b: Conduct a review of current initiatives | Not Started | Getting Started—DCLT has started an inventory of current initiatives in place | Partially Installed—DCLT has completed inventory of initiatives and identified areas for conversation and decisions | Installed—DCLT has identified action steps to organize-align and eliminate initiatives | |

| Step 2c: Conduct staff utilization | Not Started | Getting started—DCLT has started conversations about current status of roles within an integrated model | Partially Installed—DCLT has reviewed resources time allocations and job descriptions to determine any needed changes | Installed—Job descriptions have been modified to allow all school and community staff to work within an integrated system | |

| Step 2d: Review existing school and community data | Not Started | Getting Started—DCLT has started a review of both school and community data | Partially Installed—DCLT has conducted an initial comprehensive review of both school and community data | Installed—DCLT has conducted an initial comprehensive review of both school and community data and gathered family and youth perception data | |

| Step 3: Establish common mission | Not Started | Getting started with conversations to understand current partners missions and goals | Partially Installed—DCLT has reviewed existing mission statement of all partners and prioritized need through consensus process | Installed—DCLT has adopted a current mission statement that defines vision of integrated approach | |

| Step 4: Establish DCLT Procedures and Routines | Step 4a: Selecting and installing a universal screener | Not Started | Getting Started—DCLT is researching and determining fit of universal screener | Partially Installed—DCLT has selected screener and determining procedures | Installed—Schools have completed universal screening at least once |

| Step 4b: Establish a request for assistance process | Not Started | Getting started—DCLT is examining current pathways to requesting support for both school and community systems | Partially Installed—Request for assistance process is in place for only one system (i.e., school or community partner) | Installed—A single request for assistance process is in place within one continuum of support | |

| Step 4c: Process for selecting interventions | Not Started | Getting started—DCLT has completed an inventory of interventions | Partially Installed—DCLT has made decisions about interventions to eliminate, modify, or add based upon gaps in intervention inventory and needs in school and community data | Installed—DCLT has consensus for a single continuum of interventions to prioritize for installing | |

| Step 4d: Process to monitor fidelity of interventions | Not Started | Getting started—None or few interventions have fidelity measures identified with procedures defined for utilizing measures | Partially Installed—Some (more than 50%) of interventions have fidelity measures identified with procedures defined for utilizing measures | Installed—All interventions have fidelity measures identified with procedures defined for utilizing measures | |

| Step 4e: Process to monitor outcomes of interventions | Not Started | Getting started—None or few interventions have outcome measures identified with procedures defined for utilizing measures | Partially Installed—Some (more than 50%) of interventions have outcome measures identified with procedures defined for utilizing measures | Installed—All interventions have outcome measures identified with procedures defined for utilizing measures | |

| Step 5: Establish action plan to support demonstration sites | Step 5a: Evaluation Plan | Not Started | Getting started—Data sources are identified via a grant or another funding source but DCLT commitment and prioritization has not occurred | Partially Installed—Data sources are identified and prioritized without a formal plan or do not include data sources for outcome-fidelity and perception | Installed—An evaluation plan is written and has data sources for outcome-fidelity and perception |

| Step 5b: Develop a plan for professional development and coaching | Not Started | Getting started—Initial conversations about needs and a PD and coaching plan have occurred | Partially Installed—Formal needs assessment and/or data analysis has occurred to begin prioritizing needs | Installed—A professional development and coaching plan is developed based upon an action and evaluation plan | |

| Step 5c: Selecting demonstration schools | Not Started | Getting started—Initial conversations about demonstration sites have been started | Partially Installed—Determining criteria for selecting demonstration sites is being defined | Installed—Demonstration sites have been selected | |

| Step 5d: Finalizing MOU | Not Started | Getting started—an MOU already existed between partners and messages do not fully reflect an integrated system | Partially Installed—MOU exists but key messages of integrated system are not fully reflected or MOU with some but not all partners | Installed—MOU reflecting integrated system messages is in place with all partners | |

| Year | One Time | Two Times | Three Times | Total Districts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | 0 | 4 | 15 | 19 |

| Year 2 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 18 |

| Year 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| Project | Baseline–Y1 | Baseline–Y2 | Baseline–Y3 | Y1–Y2 | Y1–Y3 | Y2–Y3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project One | ↑ 40% | ↑ 49% | NA | ↑ 9% | NA | NA |

| Project Two | ↑ 26% | ↑ 32% | ↑ 57% | ↑ 7% | ↑ 31% | ↑ 25% |

| Project Three | ↑ 23% | ↑ 41% | ↑ 51% | ↑ 18% | ↑ 28% | ↑ 10% |

| Average | 36% | 41% | NA | 11% | NA | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pohlman, K.B.; Jones, K.; Lira, J.R.; Norton, J.; Perales, K. Interconnecting District and Community Partners to Improve School-Level Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Health. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091225

Pohlman KB, Jones K, Lira JR, Norton J, Perales K. Interconnecting District and Community Partners to Improve School-Level Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Health. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091225

Chicago/Turabian StylePohlman, Kathryn B., Kayla Jones, Juan R. Lira, Jennifer Norton, and Kelly Perales. 2025. "Interconnecting District and Community Partners to Improve School-Level Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Health" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091225

APA StylePohlman, K. B., Jones, K., Lira, J. R., Norton, J., & Perales, K. (2025). Interconnecting District and Community Partners to Improve School-Level Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Health. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091225