The Impact of Incidental Fear on Empathy Towards In-Group and Out-Group Pain

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Current Project

2. Experiment 1

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Stimulus

2.1.3. Measure

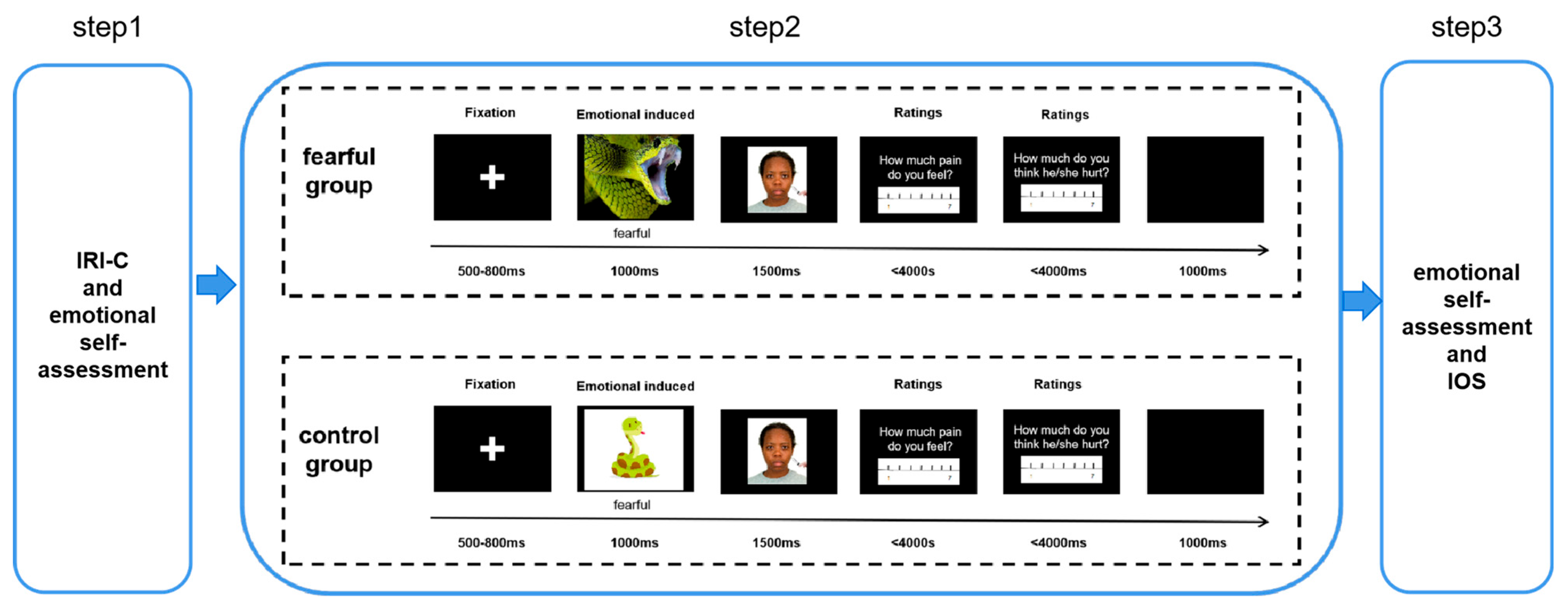

2.1.4. Procedure

2.1.5. Data Analysis

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Manipulation Check

2.2.2. Self-Target Overlap

2.2.3. IRI-C

2.2.4. Empathy Task

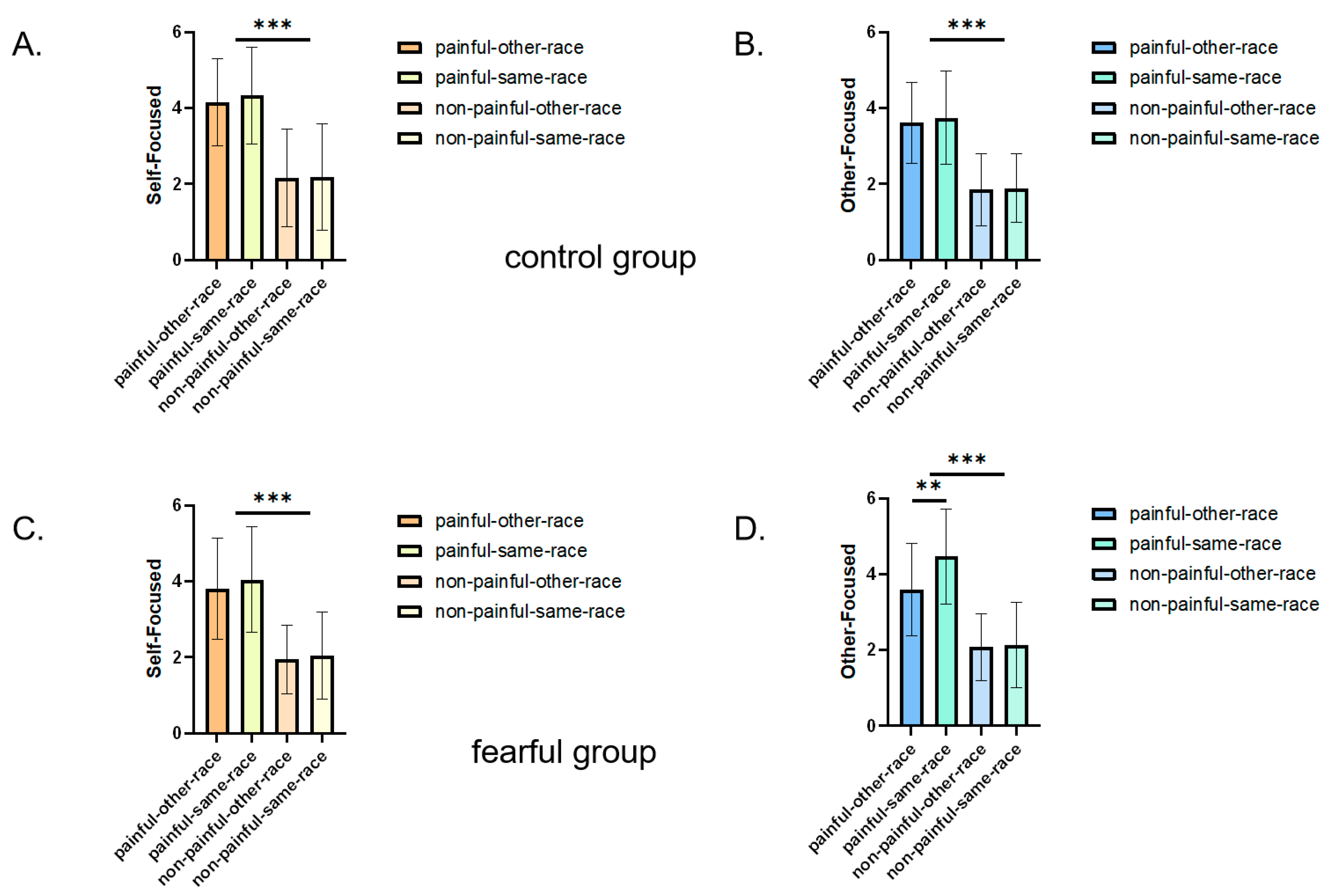

2.2.5. Self-Focused Empathy

2.2.6. Other-Focused Empathy

2.3. Discussion

3. Experiment 2

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Stimulus

3.1.3. Measure

3.1.4. Procedure

3.1.5. Data Analysis

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Manipulation Check

3.2.2. IRI-C

3.2.3. Self-Target Overlap

3.2.4. Empathy Task

3.2.5. Self-Focused Empathy

3.2.6. Other-Focused Empathy

3.3. Discussion

4. General Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Research

4.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aron, A., Aron, E. N., & Smollan, D. (1992). Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(4), 596–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R. T., Macaluso, E., Avenanti, A., Santangelo, V., Cazzato, V., & Aglioti, S. M. (2013). Their pain is not our pain: Brain and autonomic correlates of empathic resonance with the pain of same and different race individuals. Human Brain Mapping, 34(12), 3161–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenhausen, G. V., Kramer, G. P., & Süsser, K. (1994). Happiness and stereotypic thinking in social judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(4), 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenhausen, G. V., Mussweiler, T., Gabriel, S., & Moreno, K. N. (2001). Affective influences on stereotyping and intergroup relations. In Handbook of affect and social cognition (pp. 319–343). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau, E. G., Cikara, M., & Saxe, R. (2017). Parochial empathy predicts reduced altruism and the endorsement of passive harm. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(8), 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, B. K., Im, D., Harada, T., Kim, J.-S., Mathur, V. A., Scimeca, J. M., Parrish, T. B., Park, H. W., & Chiao, J. Y. (2011). Cultural influences on neural basis of intergroup empathy. NeuroImage, 57(2), 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, B. K., Melani, I., & Hong, Y. (2020). How USA-centric is psychology? An archival study of implicit assumptions of generalizability of findings to human nature based on origins of study samples. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(7), 928–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y., & Han, S. (2008). Temporal dynamic of neural mechanisms involved in empathy for pain: An event-related brain potential study. Neuropsychologia, 46(1), 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frith, U., & Frith, C. D. (2003). Development and neurophysiology of mentalizing. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 358(1431), 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, M. J., Raver, J. L., Nishii, L., Leslie, L. M., Lun, J., Lim, B. C., Duan, L., Almaliach, A., Ang, S., Arnadottir, J., Aycan, Z., Boehnke, K., Boski, P., Cabecinhas, R., Chan, D., Chhokar, J., D’Amato, A., Subirats Ferrer, M., Fischlmayr, I. C., … Yamaguchi, S. (2011). Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. Science, 332(6033), 1100–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S. (2018). Neurocognitive basis of racial ingroup bias in empathy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22(5), 400–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, G., Silani, G., Preuschoff, K., Batson, C. D., & Singer, T. (2010). Neural responses to ingroup and outgroup members’ suffering predict individual differences in costly helping. Neuron, 68(1), 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, G., Choma, B. L., Boisvert, J., Hafer, C. L., MacInnis, C. C., & Costello, K. (2013). The role of intergroup disgust in predicting negative outgroup evaluations. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(2), 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., & Han, S. (2014). Shared beliefs enhance shared feelings: Religious/irreligious identifications modulate empathic neural responses. Social Neuroscience, 9(6), 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruglanski, A. (2010). Feelings-as-information theory. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Feelings-as-Information-Theory-Kruglanski/c1231a350cde516c62ef294c1e061314acd9350a?p2df (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Lerner, J. S., Li, Y., & Weber, E. U. (2013). The financial costs of sadness. Psychological Science, 24(1), 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C., Chai, J. W., & Yu, R. (2016). Negative incidental emotions augment fairness sensitivity. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 24892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D. S., Correll, J., & Wittenbrink, B. (2015). The Chicago face database: A free stimulus set of faces and norming data. Behavior Research Methods, 47(4), 1122–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, D. M., Devos, T., & Smith, E. R. (2000). Intergroup emotions: Explaining offensive action tendencies in an intergroup context. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(4), 602–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekawi, Y., Bresin, K., & Hunter, C. D. (2016). White fear, dehumanization, and low empathy: Lethal combinations for shooting biases. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22(3), 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocaiber, I., Sanchez, T. A., Pereira, M. G., Erthal, F. S., Joffily, M., Araujo, D. B., Volchan, E., & De Oliveira, L. (2011). Antecedent descriptions change brain reactivity to emotional stimuli: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of an extrinsic and incidental reappraisal strategy. Neuroscience, 193, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, C. D., McDonald, M. M., Asher, B. D., Kerr, N. L., Yokota, K., Olsson, A., & Sidanius, J. (2012). Fear is readily associated with an out-group face in a minimal group context. Evolution and Human Behavior, 33(5), 590–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, C. D., Olsson, A., Ho, A. K., Mendes, W. B., Thomsen, L., & Sidanius, J. (2009). Fear extinction to an out-group face: The role of target gender. Psychological Science, 20(2), 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nudelman, M. F., Portugal, L. C. L., Mocaiber, I., David, I. A., Rodolpho, B. S., Pereira, M. G., & Oliveira, L. D. (2022). Long-term influence of incidental emotions on the emotional judgment of neutral faces. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 772916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phaf, R. H., & Rotteveel, M. (2005). Affective modulation of recognition bias. Emotion, 5(3), 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M. T., Barreto, M., Karl, A., & Lawrence, N. (2021). Incidental fear reduces empathy for an out-group’s pain. Emotion, 21(3), 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rösler, I. K., & Amodio, D. M. (2022). Neural basis of prejudice and prejudice reduction. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 7(12), 1200–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessa, P., Meconi, F., Castelli, L., & Dell’Acqua, R. (2014). Taking one’s time in feeling other-race pain: An event-related potential investigation on the time-course of cross-racial empathy. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9(4), 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, F., & Han, S. (2012). Manipulations of cognitive strategies and intergroup relationships reduce the racial bias in empathic neural responses. NeuroImage, 61(4), 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, T., Seymour, B., O’Doherty, J., Kaube, H., Dolan, R. J., & Frith, C. D. (2004). Empathy for pain involves the affective but not sensory components of pain. Science, 303(5661), 1157–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M. L., Asada, N., & Malenka, R. C. (2021). Anterior cingulate inputs to nucleus accumbens control the social transfer of pain and analgesia. Science, 371(6525), 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stietz, J., Jauk, E., Krach, S., & Kanske, P. (2019). Dissociating empathy from perspective-taking: Evidence from intra- and inter-individual differences research. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, 33, 94–109. Available online: https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=c87dcc1ad18893fe9c18d934a1972da3 (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Tugade, M. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(2), 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohs, K. D., Baumeister, R. F., & Loewenstein, G. (Eds.). (2007). Do emotions help or hurt decisionmaking? A hedgefoxian perspective. Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

| Other-Focused Empathy | Self-Focused Empathy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | Pain | Non-Pain | Pain | Non-Pain | ||||

| Other Race | Same Race | Other Race | Same Race | Other Race | Same Race | Other Race | Same Race | |

| Fear | 3.60 ± 1.21 | 4.47 ± 1.25 | 2.08 ± 0.89 | 2.14 ± 1.13 | 3.81 ± 1.34 | 4.05 ± 1.39 | 1.95 ± 0.91 | 2.05 ± 1.14 |

| Control | 3.61 ± 1.07 | 3.75 ± 1.23 | 1.86 ± 0.95 | 1.89 ± 0.90 | 4.16 ± 1.14 | 4.33 ± 1.27 | 2.16 ± 1.28 | 2.18 ± 1.41 |

| Other-Focused Empathy | Self-Focused Empathy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 2 | Pain | Non-Pain | Pain | Non-Pain | ||||

| Other School | Own School | Other School | Own School | Other School | Own School | Other School | Own School | |

| Fear | 3.55 ± 1.14 | 3.54 ± 1.03 | 2.32 ± 0.77 | 2.28 ± 0.86 | 3.77 ± 1.39 | 3.77 ± 1.41 | 2.34 ± 0.78 | 2.28 ± 0.87 |

| Control | 3.64 ± 1.43 | 4.68 ± 1.28 | 2.55 ± 1.00 | 2.40 ± 0.98 | 3.98 ± 1.23 | 3.79 ± 1.34 | 2.57 ± 1.07 | 2.37 ± 1.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, B.; Chi, W.; Ye, W.; Dai, T.; Wang, Y. The Impact of Incidental Fear on Empathy Towards In-Group and Out-Group Pain. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091186

Sun B, Chi W, Ye W, Dai T, Wang Y. The Impact of Incidental Fear on Empathy Towards In-Group and Out-Group Pain. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091186

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Binghai, Weihao Chi, Weihao Ye, Tinghui Dai, and Yaoyao Wang. 2025. "The Impact of Incidental Fear on Empathy Towards In-Group and Out-Group Pain" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091186

APA StyleSun, B., Chi, W., Ye, W., Dai, T., & Wang, Y. (2025). The Impact of Incidental Fear on Empathy Towards In-Group and Out-Group Pain. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091186