Time Perspective and Health Behaviors in Chronic Disease Patients: A Chain Mediation Model of Illness Perception via Temporal Self-Regulation Theory

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypothesis

2.1. Temporal Self-Regulation Theory

2.2. Time Perspective and Health Behaviors

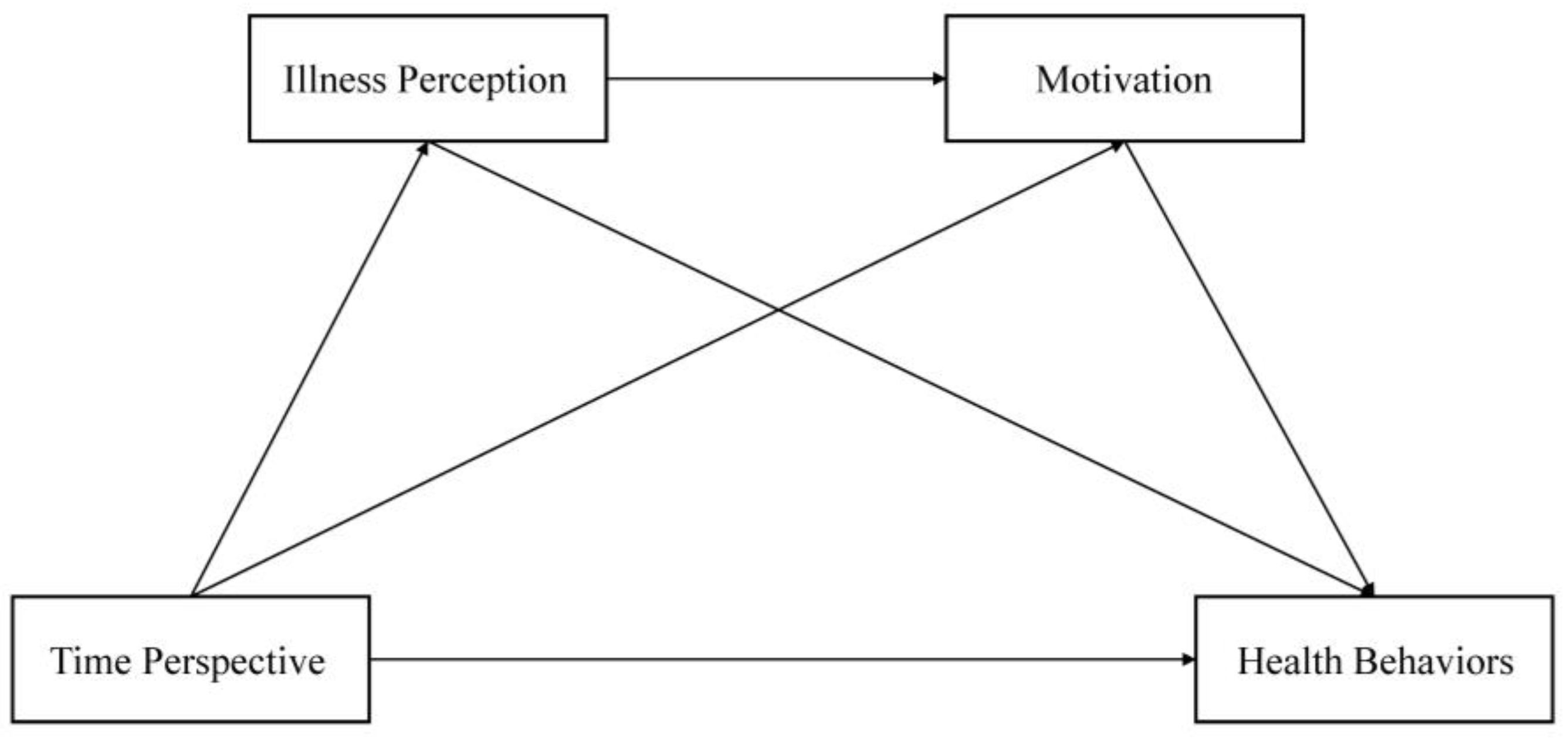

2.3. Mediating Roles of Illness Perception and Health Behavior Motivation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

3.2. Sample Size

3.3. General Demographic Data

3.4. Assessment Instruments

3.4.1. Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory

3.4.2. Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire

3.4.3. Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire

3.4.4. Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile—II

3.5. Identifying Fraudulent and Careless Responses

3.6. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

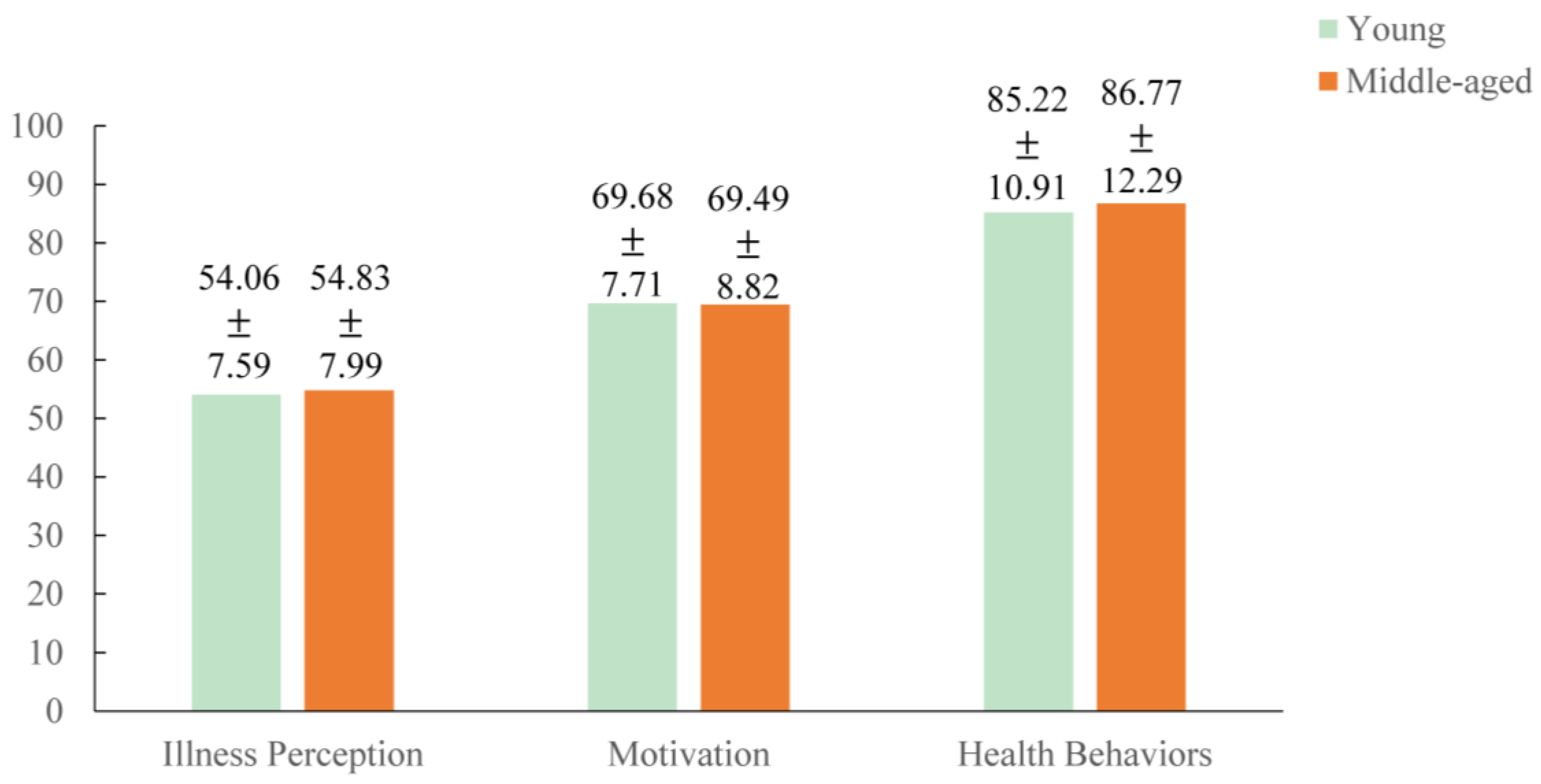

4.1. Characteristics of Participants

4.2. Common Method Bias Test

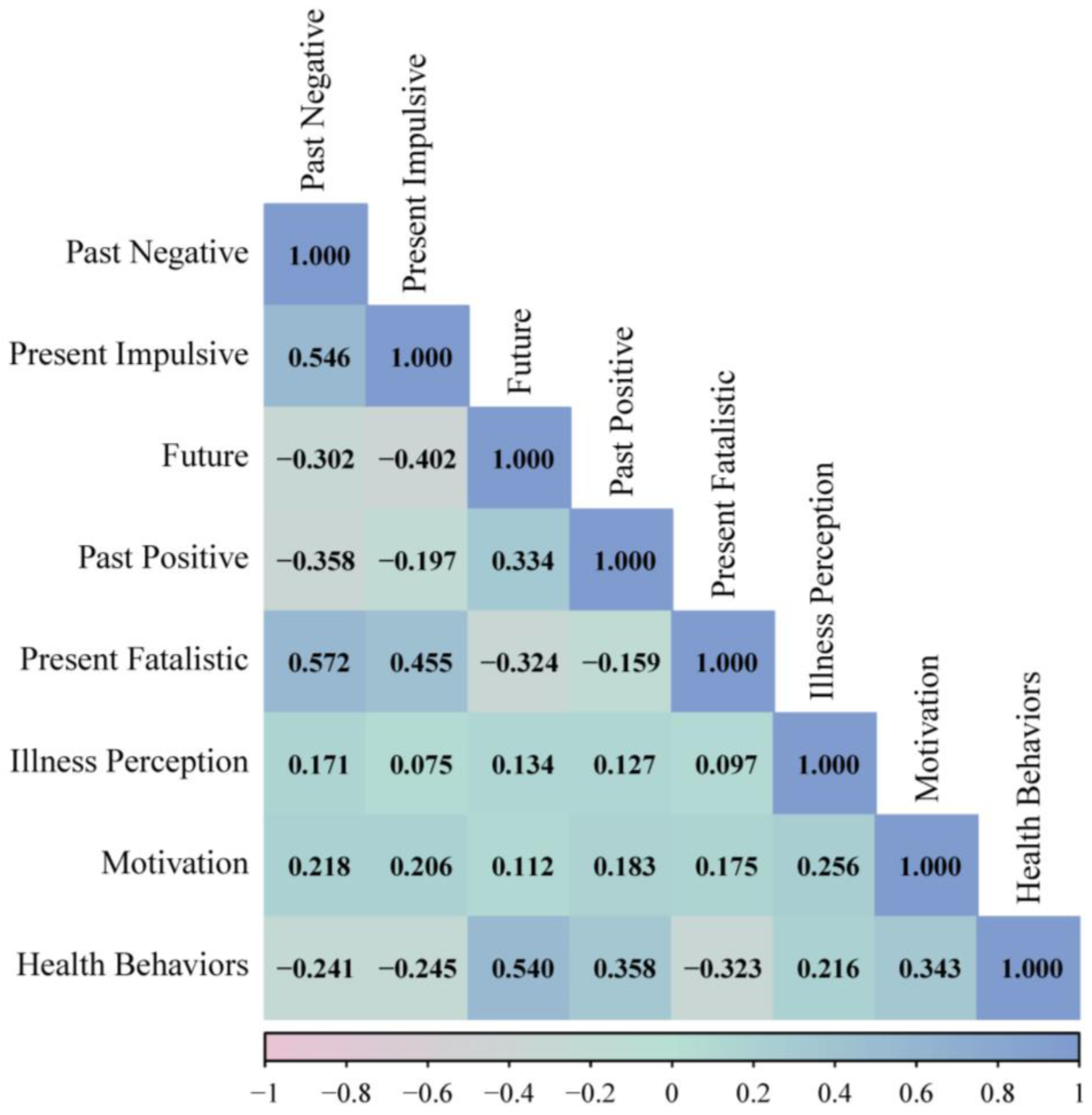

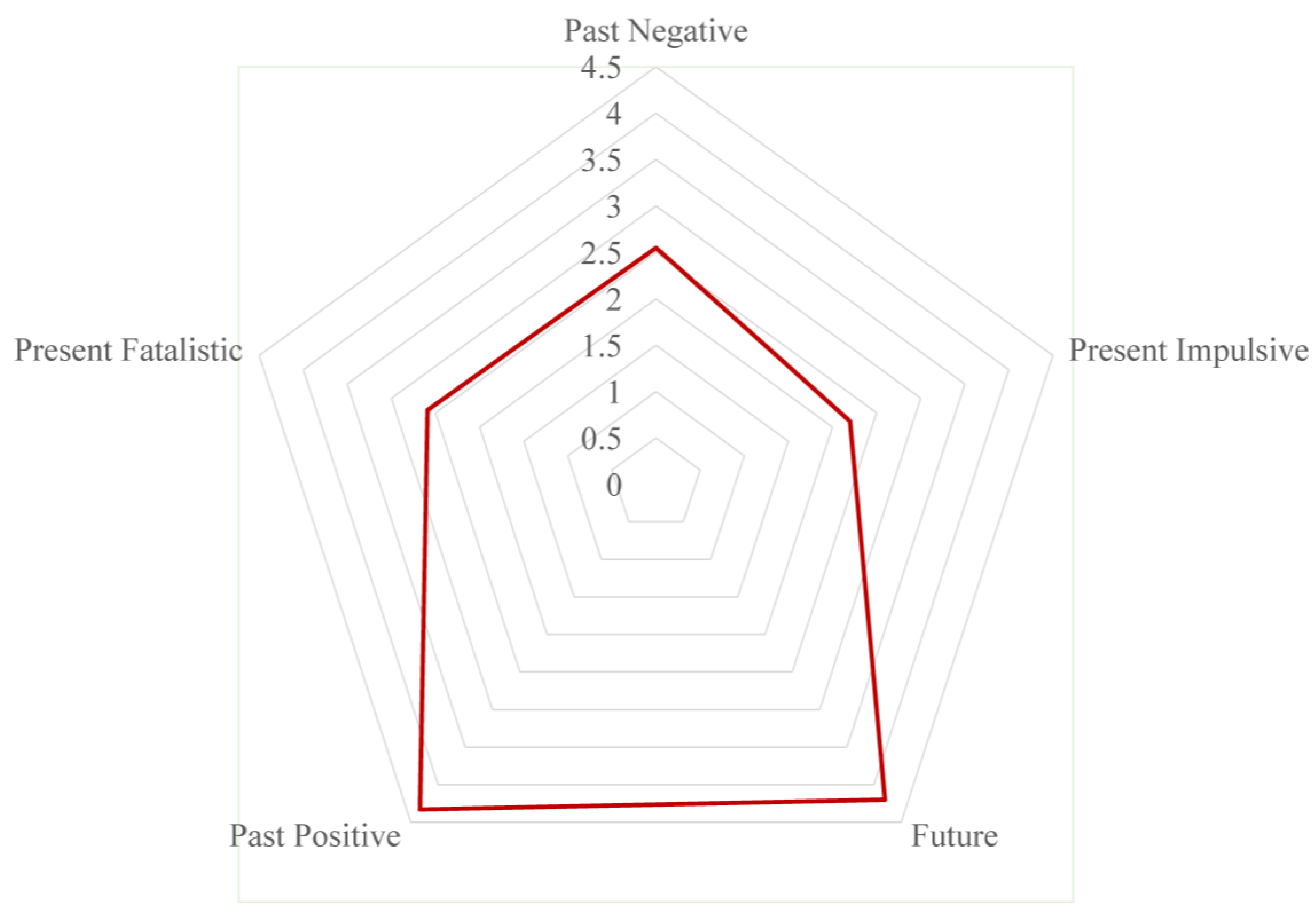

4.3. Description of Variable Distributions and Correlations

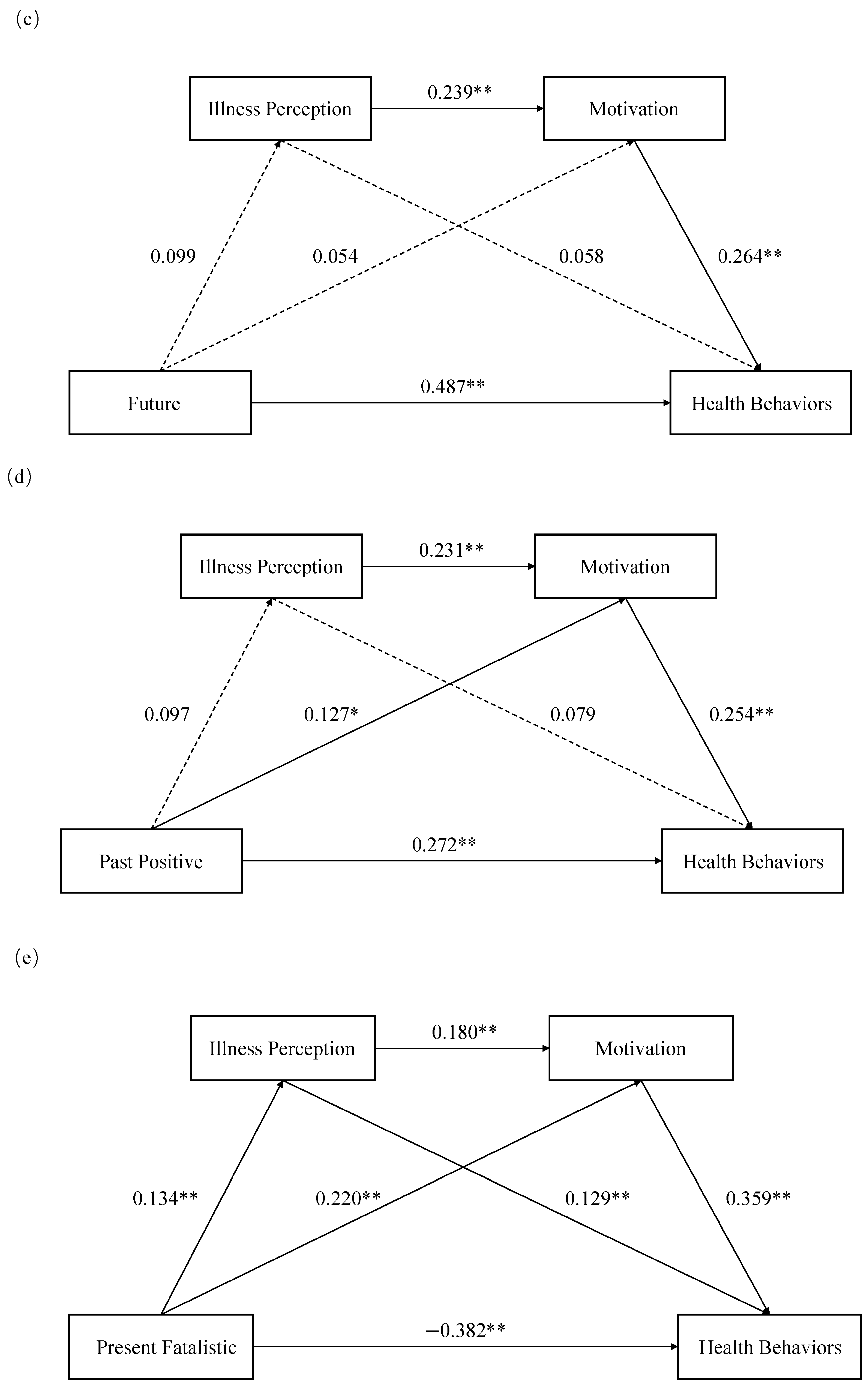

4.4. Model Verification and Mediating Effect Test

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Faraj, H., Kum, C., Warner, L., Lee, R. C., Becker, R., & Bakas, T. (2025). Mental health factors and lifestyle adherence after myocardial infarction: An integrative review. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 47(6), 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allemand, M., Olaru, G., & Hill, P. L. (2025). Future time perspective and depression, anxiety, and stress in adulthood. Anxiety Stress Coping, 38(1), 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(Pt 4), 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braitman, A. L., & Henson, J. M. (2015). The impact of time perspective latent profiles on college drinking: A multidimensional approach. Substance Use & Misuse, 50(5), 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broadbent, E., Petrie, K. J., Main, J., & Weinman, J. (2006). The brief illness perception questionnaire. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 60(6), 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L., Gou, X., Yang, S., Dong, H., Dong, F., & Wu, J. (2025). Identifying potential action points for reducing kinesiophobia among atrial fibrillation patients: A network and DAG analysis. Quality of Life Research, 34(5), 1253–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y., Du, J., Zhou, N., Song, Y., Wang, W., & Hong, X. (2023). Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of dyslipidaemia and their determinants: Results from a population-based survey of 60 283 residents in eastern China. BMJ Open, 13(12), e75860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, H. S. J., Sim, K. L. D., Cao, X., & Chair, S. Y. (2019). Motivation, challenges and self-regulation in heart failure self-care: A theory-driven qualitative study. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 26(5), 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comachio, J., Poulsen, A., Bamgboje-Ayodele, A., Tan, A., Ayre, J., Raeside, R., Roy, R., & O’Hagan, E. (2024). Identifying and counteracting fraudulent responses in online recruitment for health research: A scoping review. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, 20(3), 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Credamo. (2025, March 24). About Credamo. Available online: https://www.credamo.world/#/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Csdt. (2025, March 24). Self-regulation questionnaires (SRQ). Available online: https://selfdeterminationtheory.org/self-regulation-questionnaires/ (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- De La Cruz, M., Zarate, A., Zamarripa, J., Castillo, I., Borbon, A., Duarte, H., & Valenzuela, K. (2021). Grit, self-efficacy, motivation and the readiness to change index toward exercise in the adult population. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 732325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Los, S. M., Fusinato-Ponce, C., & Fernández-Alcántara, M. (2023). Motivational influences on health, well-being, and lifestyle: Validation of the Spanish version of the treatment self-regulation questionnaire in four health domains. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(11), 2328–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L., Yang, M., & Marcoulides, K. M. (2018). Structural equation modeling with many variables: A systematic review of issues and developments. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, E. A., Heijenbrok-Kal, M. H., van Kooten, F., van der Slot, W., Manuputty, J., Utens, C., Ribbers, G. M., & van den Berg-Emons, R. (2025). Associations of environmental and personal factors, participation and health-related quality of life with physical activity and sedentary behavior in people with subarachnoid hemorrhage: A cross-sectional accelerometer-based study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, S., Ru, Y., Wang, J., Yang, H., Xu, Y., Zhou, Q., Pan, H., & Wang, M. (2024). Effects of episodic future thinking in health behaviors for weight loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 152, 104667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, R., Norman, P., & Webb, T. L. (2017). Using temporal self-regulation theory to understand healthy and unhealthy eating intentions and behaviour. Appetite, 116, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaskin, C. J., & Happell, B. (2013). Power of mental health nursing research: A statistical analysis of studies in the International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 22(1), 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y., Zheng, Y., & Swerts, M. (2019). Which is in front of chinese people, past or future? The effect of language and culture on temporal gestures and spatial conceptions of time. Cognitive Science, 43(12), e12804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S., Cui, P., Wang, P., Liu, W., Shao, M., Li, T., & Chen, C. (2025). The chain mediating effects of psychological capital and illness perception on the association between social support and acceptance of illness among Chinese breast cancer patients: A cross-sectional study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 75, 102800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthrie, L. C., Butler, S. C., Lessl, K., Ochi, O., & Ward, M. M. (2014). Time perspective and exercise, obesity, and smoking: Moderation of associations by age. American Journal of Health Promotion, 29(1), 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, P. A. (2013). Temporal self-regulation theory. In M. D. Gellman, & J. R. Turner (Eds.), Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine (pp. 1960–1963). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P. A., & Fong, G. T. (2007). Temporal self-regulation theory: A model for individual health behavior. Health Psychology Review, 1(1), 6–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P. A., & Fong, G. T. (2013). Temporal self-regulation theory: Integrating biological, psychological, and ecological determinants of health behavior performance. In P. A. Hall (Ed.), Social neuroscience and public health: Foundations for the science of chronic disease prevention (pp. 35–53). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C., Liu, S., Ding, X., Zhang, Y., Hu, J., Yu, F., & Hu, D. (2025). Exploring the relationship between illness perception, self-transcendence, and demoralization in patients with lung cancer: A latent profile and mediation analysis. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing, 12, 100638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J., Wang, Z., Fu, Y., Wang, Y., Yi, S., Ji, F., & Nagata, J. M. (2024). Associations between screen use while eating and eating disorder symptomatology: Exploring the roles of mindfulness and intuitive eating. Appetite, 197, 107320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henson, J. M., Carey, M. P., Carey, K. B., & Maisto, S. A. (2006). Associations among health behaviors and time perspective in young adults: Model testing with boot-strapping replication. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(2), 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W., & Yu, H. (2025). Confucian culture and corporate innovation. Technology in Society, 81, 102783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, P., Wang, X., Li, A., Dong, H., & Ji, M. (2023). Time perspective, dietary behavior, and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Nursing Research, 72(6), 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooij, D., Kanfer, R., Betts, M., & Rudolph, C. W. (2018). Future time perspective: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(8), 867–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larki, A., Tahmasebi, R., & Reisi, M. (2018). Factors predicting self-care behaviors among low health literacy hypertensive patients based on health belief model in Bushehr district, south of Iran. International Journal of Hypertension, 2018, 9752736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, B., Tang, C., Holroyd, E., & Wong, W. (2024). Challenges and implications for menopausal health and help-seeking behaviors in midlife women from the united states and China in light of the COVID-19 pandemic: Web-based panel surveys. JMIR Public Health Surveill, 10, e46538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C. K., & Liao, L. L. (2022). Delay discounting, time perspective, and self-schemas in adolescent alcohol drinking and disordered eating behaviors. Appetite, 168, 105703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X., Wang, C., Lyu, H., Worrell, F. C., & Mello, Z. R. (2023). Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Zimbardo time perspective inventory. Current Psychology, 42(16), 13547–13559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P., Wu, Q., Cheng, Y., Zhuo, Y., Li, Z., Ye, Q., & Yang, Q. (2024). Associations of illness perception and social support with fear of progression in young and middle-aged adults with digestive system cancer: A cross-sectional study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 70, 102586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, A., & Mullan, B. (2021). Exploring temporal self-regulation theory to predict sugar-sweetened beverage consumption. Psychology & Health, 36(3), 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, C., Ingles, J., Broadbent, E., Skinner, J. R., & Kasparian, N. A. (2020). How patient perceptions shape responses and outcomes in inherited cardiac conditions. Heart Lung and Circulation, 29(4), 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W., Chen, S., Chen, X., Ma, Y., Wang, T., Sun, X., Wang, Y., Ding, G., & Wang, Y. (2024). Trends in major non-communicable diseases and related risk factors in China 2002–2019: An analysis of nationally representative survey data. The Lancet Regional Health—Western Pacific, 43, 100809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streiner, D. L. (2003). Starting at the beginning: An introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. Journal of Personality Assessment, 80(1), 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S., Cao, X., Li, X., Nyeong, Y., Zhang, X., & Wang, Z. (2023). Avoiding threats, but not acquiring benefits, explains the effect of future time perspective on promoting health behavior. Heliyon, 9(9), e19842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D., Chen, M., Huang, X., Zhang, G., Zeng, L., Zhang, G., Wu, S., & Wang, Y. (2023). SRplot: A free online platform for data visualization and graphing. PLoS ONE, 18(11), e294236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H., Zhang, W., Weng, Y., Zhang, X., Shen, H., Li, X., Liu, Y., Liu, W., Xiao, H., & Jing, H. (2025). Dietary self-management behavior and associated factors among breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: A latent profile analysis. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 75, 102825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y., Xu, T., Wang, X., Liu, C., Wu, Y., Liu, M., Xiao, T., & Qiu, X. (2024). The relationships between emerging adults self-efficacy and motivation levels and physical activity: A cross-sectional study based on the self-determination theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1342611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, H. L., Yen, M., & Fetzer, S. (2010). Health promotion lifestyle profile-II: Chinese version short form. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(8), 1864–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villaron, C., Marqueste, T., Eisinger, F., Cappiello, M. A., Therme, P., & Cury, F. (2017). Links between personality, time perspective, and intention to practice physical activity during cancer treatment: An exploratory study. Psychooncology, 26(4), 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H., Zhu, Y., Shi, J., Huang, X., & Zhu, X. (2022). Time perspective and family history of alcohol dependence moderate the effect of depression on alcohol dependence: A study in Chinese psychiatric clinics. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 903535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J. M., & Li, Y. Q. (2022). Soft economic incentives and soft behavioral interventions on the public’s green purchasing behaviour—The evidence from China. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 2477–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y., & Singer, J. A. (2020). A cross-cultural study of self-defining memories in Chinese and American college students. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 622527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, M. K., & Meade, A. W. (2023). Dealing with careless responding in survey data: Prevention, identification, and recommended best practices. Annual Review of Psychology, 74, 577–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, G., Taylor, E., Ng, V., Murrell, A., Patil, A., van der Touw, T., Wolden, M., Andronicos, N., & Smart, N. A. (2023). Estimating the effect of aerobic exercise training on novel lipid biomarkers: A systematic review and multivariate meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sports Medicine, 53(4), 871–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y., & Yang, Y. (2019). RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: The story they tell depends on the estimation methods. Behavior Research Methods, 51(1), 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yiaslas, T. A., Rogers-Soeder, T. S., Ono, G., Kitazono, R. E., & Sood, A. (2024). Effect of a 15-week whole foods, plant-based diet, physical activity, and stress management intervention on cardiometabolic risk factors in a population of US veterans: A retrospective analysis. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 1300751140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaragoza, S. A., Salgado, S., Shao, Z., & Berntsen, D. (2015). Event centrality of positive and negative autobiographical memories to identity and life story across cultures. Memory, 23(8), 1152–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X., & Wu, J. (2025). Temporal trends and relevant factors of hypertension in China: A cross-sectional study based on national surveys from 2002 to 2019. Blood Pressure, 34, 2468172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X., Zhang, M., Sui, H., Li, C., Huang, Z., Liu, B., Song, X., Liao, S., Yu, M., Luan, T., Zuberbier, T., Wang, L., Zhao, Z., & Wu, J. (2023). Prevalence and risk factors of allergic rhinitis among Chinese adults: A nationwide representative cross-sectional study. World Allergy Organization Journal, 16(3), 100744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X., Jr., Lynch, J. G., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (2015). Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. In M. Stolarski, N. Fieulaine, & W. van Beek (Eds.), Time perspective theory; review, research and application: Essays in honor of Philip G. Zimbardo (pp. 17–55). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Number (%)/M ± SD |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 147 (37.6) |

| Female | 244 (62.4) |

| Age (years) | 8.77 |

| Educational level | |

| High school or below | 8 (2.0) |

| Secondary school/technical school/vocational high school | 7 (1.8) |

| Junior college | 44 (11.3) |

| Bachelor degree | 258 (66.0) |

| Master’s degree or above | 74 (19.0) |

| Place of residence | |

| Urban | 364 (93.1) |

| Rural | 27 (6.9) |

| Marital status | |

| Unmarried | 119 (30.4) |

| Married | 267 (68.3) |

| Divorced | 4 (1.0) |

| Widowed | 1 (0.3) |

| Monthly income (RMB) | |

| ≤3000 | 46 (11.8) |

| 3001~5000 | 60 (15.3) |

| 5001~8000 | 109 (27.9) |

| >8000 | 176 (45.0) |

| Employment status | |

| In school | 47 (12.0) |

| Employed | 332 (84.9) |

| Retired | 3 (0.8) |

| Freelance work | 9 (2.3) |

| Self-reported chronic disease | |

| Chronic digestive diseases | 174 (44.5) |

| Endocrine and metabolic disorders | 168 (43.0) |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 117 (29.9) |

| Immune diseases | 70 (17.9) |

| Chronic lung disease | 32 (8.2) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 12 (3.1) |

| Others | 26 (6.4) |

| Variables | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Past Negative | 17.92 | 5.53 |

| Present Impulsive | 8.81 | 3.20 |

| Future | 21.08 | 2.50 |

| Past Positive | 26.06 | 2.85 |

| Present Fatalistic | 7.80 | 2.82 |

| Illness Perception | 54.15 | 7.64 |

| Motivation | 69.65 | 7.84 |

| Health Behaviors | 84.40 | 11.08 |

| Variables | Effect Formation | Effect Size | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Past negative → Health behaviors | |||

| Total | −0.407 | (−0.605, −0.209) | |

| Direct | −0.670 | (−0.858, −0.481) | |

| Present impulsive → Health behaviors | |||

| Total | −0.556 | (−0.912, −0.201) | |

| Direct | −0.997 | (−1.337, −0.656) | |

| Future → Health behaviors | |||

| Total | 2.271 | (1.884, 2.657) | |

| Direct | 2.155 | (1.789, 2.522) | |

| Past positive → Health behaviors | |||

| Total | 1.234 | (0.873, 1.596) | |

| Direct | 1.057 | (0.708, 1.406) | |

| Present fatalistic → Health behaviors | |||

| Total | −1.139 | (−1.510, −0.769) | |

| Direct | −1.503 | (−1.846, −1.160) |

| Variables | Path | Effect Size | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Past negative → Health behaviors | |||

| Past negative → Illness perception → Health behaviors | 0.068 | (0.024, 0.130) | |

| Past negative → Motivation → Health behaviors | 0.162 | (0.077, 0.256) | |

| Past negative → Illness perception → Motivation → Health behaviors | 0.032 | (0.012, 0.059) | |

| Present impulsive → Health behaviors | |||

| Present impulsive → Illness perception → Health behaviors | 0.069 | (0.011, 0.154) | |

| Present impulsive → Motivation → Health behaviors | 0.330 | (0.176, 0.499) | |

| Present impulsive → Illness perception → Motivation → Health behaviors | 0.042 | (0.011, 0.079) | |

| Future → Health behaviors | |||

| Future → Illness perception → Health behaviors | 0.025 | (−0.011, 0.082) | |

| Future → Motivation → Health behaviors | 0.063 | (−0.058, 0.190) | |

| Future → Illness perception → Motivation → Health behaviors | 0.028 | (0.002, 0.064) | |

| Past positive → Health behaviors | |||

| Past positive → Illness perception → Health behaviors | 0.030 | (−0.007, 0.091) | |

| Past positive → Motivation → Health behaviors | 0.126 | (0.009, 0.259) | |

| Past positive → Illness perception → Motivation → Health behaviors | 0.022 | (0.000, 0.055) | |

| Present fatalistic → Health behaviors | |||

| Present fatalistic → Illness perception → Health behaviors | 0.068 | (0.008, 0.158) | |

| Present fatalistic → Motivation → Health behaviors | 0.254 | (0.101, 0.426) | |

| Present fatalistic → Illness perception → Motivation → Health behaviors | 0.042 | (0.009, 0.085) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lang, X.; Huang, S.; Xiao, Y. Time Perspective and Health Behaviors in Chronic Disease Patients: A Chain Mediation Model of Illness Perception via Temporal Self-Regulation Theory. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15080996

Lang X, Huang S, Xiao Y. Time Perspective and Health Behaviors in Chronic Disease Patients: A Chain Mediation Model of Illness Perception via Temporal Self-Regulation Theory. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):996. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15080996

Chicago/Turabian StyleLang, Xiaorong, Sufang Huang, and Yaru Xiao. 2025. "Time Perspective and Health Behaviors in Chronic Disease Patients: A Chain Mediation Model of Illness Perception via Temporal Self-Regulation Theory" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15080996

APA StyleLang, X., Huang, S., & Xiao, Y. (2025). Time Perspective and Health Behaviors in Chronic Disease Patients: A Chain Mediation Model of Illness Perception via Temporal Self-Regulation Theory. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15080996