Inclusive Leadership and Creative Territory Behavior: A Triple Interactive Moderating Effect Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

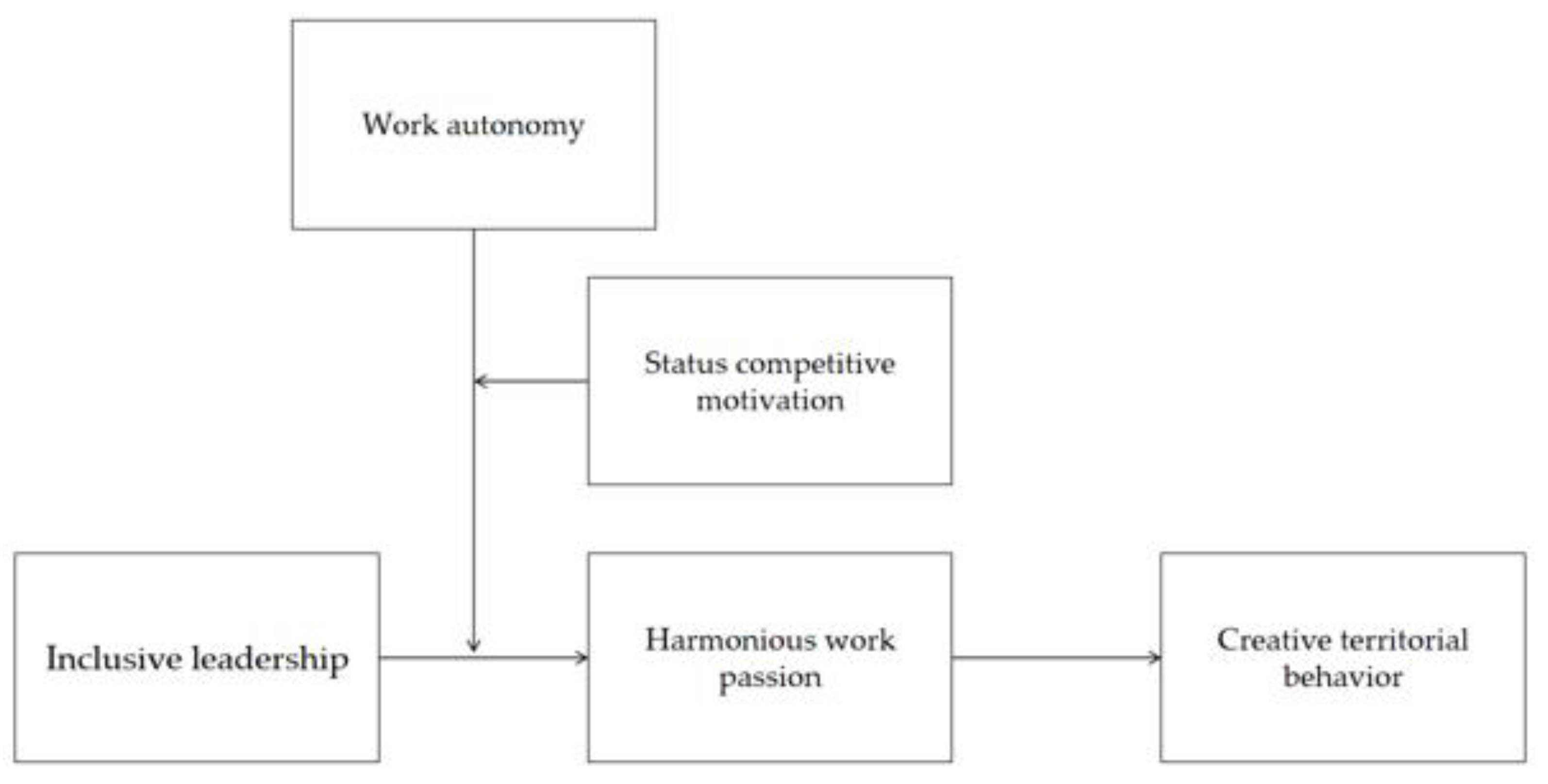

2. Theoretical Basis and Research Assumptions

2.1. Inclusive Leadership and Creative Territory Behavior

2.2. Mediating Effect of Harmonious Work Passion

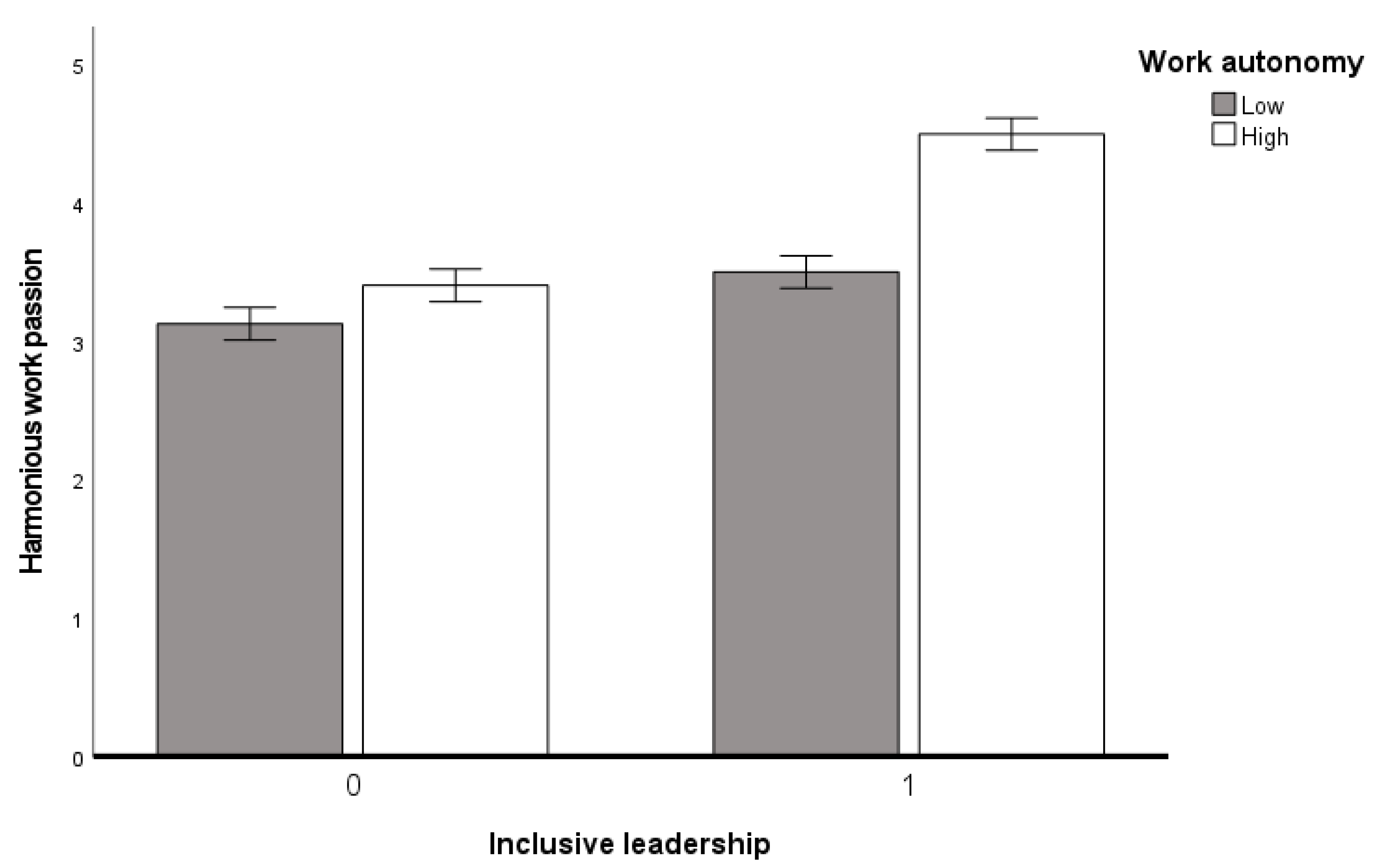

2.3. The Moderating Role of Work Autonomy

2.4. Moderating Effect of Status Competition Motivation on Work Autonomy

3. Study 1: Scenario Experiment

3.1. Study Methods

3.1.1. Study Samples

3.1.2. Experimental Design and Procedure

3.1.3. Variable Measurement

- (1)

- Inclusive leadership. This study uses a scale developed by Carmeli et al. (Carmeli et al., 2010) that contains nine items. Typical items are “My supervisor is willing to discuss with me sudden problems in work”, “My supervisor is willing to provide consultation on work-related problems”, etc. Its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.948.

- (2)

- Harmonious work passion. This system is based on Vallerand and Houlfort’s self-report scale and Chen et al.’s other-rating scale (Vallerand et al., 2003). Its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.875.

- (3)

- Creative territory behavior. A one-dimensional 4-item scale developed by Avey et al. (Avey et al., 2009) was used that contains typical items such as “feeling the need to protect one’s innovative ideas from others in the organization”. Its Cronbach alpha coefficient is 0.894.

- (4)

- Autonomy of work. This study uses the 9-item scale from the Breaugh Study (Breaugh, 1999). Typical items are “I can plan and arrange my work according to my own wishes” and “My work allows me to make my own decisions”. Its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.943.

3.2. Research Results

3.2.1. Control Check

3.2.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.2.3. Hypothesis Testing

4. Study 2: Questionnaire Survey

4.1. Data Collection and Research Samples

4.2. Measuring Tool

- (1)

- Inclusive leadership. This study uses a scale developed by Carmeli et al. (Carmeli et al., 2010) that contains nine items. Typical items are “My supervisor is willing to discuss with me sudden problems in work”, “My supervisor is willing to provide consultation on work-related problems”, etc. Its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.948.

- (2)

- Harmonious work passion. This evaluation is based on Vallerand and Houlfort’s self-report scale and Chen et al.’s other-rating scale (Vallerand et al., 2003). Its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.875.

- (3)

- Creative territory behavior. A one-dimensional 4-item scale developed by Avey et al. (Avey et al., 2009) was used, containing typical items such as “feeling the need to protect one’s innovative ideas from others in the organization”. Its Cronbach alpha coefficient is 0.894.

- (4)

- Autonomy of work. This study uses the 9-item scale from the Breaugh Study (Breaugh, 1999). Typical items are “I can plan and arrange my work according to my own wishes” and “My work allows me to make my own decisions”. Its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.943.

- (5)

- Motivation for status competition. Cheng et al.’s (J. T. Cheng et al., 2013) scale was used, with representative items such as “I often strive to achieve my goals regardless of what the rest of the team thinks”. Its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.947.

- (6)

- Control variables. Following the recommendations of previous studies (B. C. Wang et al., 2025; J. Jiang et al., 2022; Zheng et al., 2018) and in order to rule out other factors affecting employee creative territory behavior, we controlled for individual variables, including employee gender, age, education, position, tenure, and industry.

4.3. Data Analysis and Hypothesis Testing

4.3.1. Common Method Bias

4.3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3.3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.3.4. Hypothesis Testing

- (1)

- Mediating effect test

- (2)

- Mediating effect test

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Research Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Contribution

- (1)

- Exploring the mechanism of inclusive leadership on employees’ creative territory behavior provides a new perspective and starting point for understanding the process of inhibiting employees’ creative territory behavior. Inclusive leadership is a leadership style that understands the differentiated needs of employees and accommodates their individual characteristics, which can enhance the innovation ability and core competitiveness of the organization (Tang & Zhang, 2015). Previous studies have shown that individual factors (X. Chen et al., 2023), leadership style factors (Cao & Zhao, 2022; Huang & Tang, 2020; Tan & Yuan, 2024), interpersonal factors (Deng & Xiang, 2022), and specific organizational situations have significant effects on employee territory behavior, but the negative impact of inclusive leadership on creative territory behavior lacks in-depth theoretical construction and empirical testing.

- (2)

- Expanding the internal mechanism between inclusive leadership and creative territory behavior by using the “environment–cognition–behavior” framework. Previous studies have shown that harmonious work passion is mainly influenced by leadership style, work characteristics, organizational environment, and individual traits (Slemp et al., 2021; Dwertmann & Boehm, 2016; Jansen et al., 2014; Nishii, 2013; Shore et al., 2011; Hao et al., 2018; Egan et al., 2019; Shore et al., 2011; D. Wang et al., 2022), and that it is conducive to stimulating employee creativity, positive organizational behavior, and cooperative willingness (G. Y. Wang et al., 2016; Vallerand et al., 2007; L. Chen et al., 2021; Ma & Ma, 2021; Vallerand et al., 2003; Lavigne et al., 2012; Yukhymenko-Lescroart & Sharma, 2019). However, few scholars analyze the mediating effect between inclusive leadership and employee creative territory behavior from the chain of “leadership behavior–psychological needs–behavioral outcomes”. Therefore, this paper examines the mediating effect of harmonious work passion on inclusive leadership and creative territory behavior, which provides a new explanation for understanding inclusive leadership to inhibit creative territory behavior by satisfying employee autonomy, competence, and relationship needs.

- (3)

- To explore the negative effects of the interaction of inclusive leadership, work autonomy, and status competition motivation on employees’ creative territory behavior. There are many studies that agree that job characteristics and individual traits have an impact on individual behavior, but they are all analyzed from a single factor. This study introduces the dual regulation mechanism of work autonomy and status competition motivation, enriches the boundary conditions of inclusive leadership affecting employees’ creative territory behavior, and makes up for the lack of previous studies on multiple boundary conditions.

5.3. Practice Has Inspired

- (1)

- Organizations should focus on fostering inclusive behavior in leadership, as well as fostering inclusive environments. Organizations should foster inclusive behavior in leaders by encouraging them to communicate openly and value employee feedback, by further integrating inclusive behavior into their performance management and incentive systems, by encouraging leaders to participate in training courses on how to behave inclusively (Offermann & Basford, 2013), and by fostering beliefs and cognitive complexity in support of diversity (Randel et al., 2018). Leaders can regularly discuss new ideas with employees, establish non-hierarchical communication channels to improve team psychological safety, and systematically promote inclusive behavior and creative culture by training to simulate inclusive leadership scenarios and establishing feedback mechanisms that encourage trial and error.

- (2)

- Organizations should attach importance to protecting employees’ harmonious work passion. In addition to encouraging leaders to demonstrate inclusive behavior, organizations can also adopt strategies such as creating a collaborative work environment (Ho et al., 2018), empowering employees and giving positive feedback (Vallerand et al., 2003), creating a culture that supports autonomy (D. Liu et al., 2011), and activating employees’ perception of work meaning and strengthening internal drive through task diversity and goal challenge setting (Burke et al., 2015) so as to effectively stimulate employees’ harmonious work passion.

- (3)

- Organizations should strengthen the protection of employee knowledge and creativity. The organization should take steps to clarify employee creative ownership and reduce employee creative territory behavior due to concerns about reduced competitiveness. Through intellectual property registration, project achievement recognition, and other systems, employees’ legitimate rights and interests in personal creativity are protected, and territorial defense behaviors caused by vague property rights are reduced. At the same time, employees are encouraged to actively share personal creativity, set an example of creativity sharing and experience sharing, and reward employees who contribute creativity to the organization with materials and honors.

- (4)

- Enterprises should strengthen employees’ autonomy and guide employees’ competitive motivation correctly. In order to ensure that employees are more flexible in their work and to promote their creative problem solving, it is necessary to consider moderately enhancing work autonomy when designing work. Leaders should give employees more autonomy to stimulate innovative work results, such as managers allowing employees to work according to their own needs, as well as to determine the location and pace of full empowerment. When recruiting employees and organizing teams, we can match the work with high levels of autonomy to the employees with high levels of status competition motivation. In the process of organizational management, managers should face up to the needs of employees for status, treat the status competition among employees correctly and dialectically, and guide employees to adopt positive status competition strategies.

5.4. Research Limitations and Future Prospects

- (1)

- In this study, we followed the practice of previous scholars and adopted employee self-evaluation reports. There may be a social expectation bias present that leads to the overestimation of the relationship between variables. Although we adopted multi-time point data collection to reduce instant response bias, it is still difficult to completely exclude reverse causality from cross-section data. Future studies may use multi-source evaluations (e.g., combining leadership and peer evaluations) and longitudinal follow-up designs to enhance the causal inference of conclusions.

- (2)

- This study only discusses the moderating effect of status competition motivation and verifies the sensitivity of Chinese employees to “face”. In the future, other personality traits (such as achievement motivation and risk preference) or situational factors (such as organizational culture type and industry competition intensity) should be considered. Furthermore, this study builds a model based on self-determination theory; future studies should incorporate other theories (such as resource conservation theory and social identity theory) for cross-validation, which may increase the interpretation depth of complex mechanisms. The triple interaction effect of work autonomy and status competition motivation is not significant in some situations, which may be related to the constraints of industry or task characteristics.

- (3)

- This study focused on individual-level analysis and did not explore aggregation effects at the team or organizational levels, such as the group impact of team inclusion climate on creative territory behavior. In reality, team interaction patterns and organizational innovation systems may strengthen or weaken individual behavior; therefore, further cross-level research at the team and individual levels may explain more complex mechanisms in the future.

- (4)

- This study is based on a Chinese cultural context. Chinese culture may have its particularity, such as collectivism culture, which may affect the universality of the conclusions drawn. In the future, the study scenario should be expanded to verify the model in a cross-cultural context (such as comparing Chinese and Western enterprises).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, F., Zhao, F., & Faraz, N. A. (2020). How and when does inclusive leadership curb psychological distress during a crisis? Evidence from the COVID-19 outbreak. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, B., & Bakker, E. D. (2016). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., Crossley, C. D., & Luthans, F. (2009). Psychological ownership: Theoretical extensions, measurement and relation to work outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, M., & Frese, M. (2003). Innovation is not enough: Climates for initiative and psychological safety, process innovations, and firm performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendersky, C., & Hays, N. A. (2012). Status conflict in groups. Organization Science, 23, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, B. J. (1979). Expectations. In Role theory: Expectations, identities, and behaviors. Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, E. H. (2020). Diversity, inclusive leadership, and health outcomes. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 9(7), 266–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breaugh, J. A. (1999). Further investigation of the work autonomy scales: Two studies. Journal of Business and Psychology, 13, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G., & Robinson, S. L. (2005). Territoriality in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 30(3), 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R. J., Astakhova, M. N., & Hang, H. (2015). Work passion through the lens of culture: Harmonious work passion, obsessive work passion, and work outcomes in Russia and China. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P., & Zhao, R. X. (2022). Effects of paradoxical leadership on employees’ creative territory behavior: Mediating role of team interaction and regulating role of individualism. Science and Technology Management Research, 42(2), 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P., Zhao, R. X., & You, Y. (2023). The influence of work resources on the creative territory behavior of Chinese new generation knowledgeable employees: Research based on SEM and fsQCA. Science of Science and Management of S. & T., 44(5), 161–180. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, A., Reiter-Palmon, R., & Ziv, E. (2010). Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: The mediating role of psychological safety. Creativity Research Journal, 22, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Yin, H., Chen, N., & Jing, R. T. (2021). Work passion, voice and behavior of initiating change: “Double edged sword” effects of narcissistic leadership. Journal of Management Science, 34(5), 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Lee, C., Hui, C., Lin, W., Brown, G., & Liu, J. (2023). Feeling possessive, performing well? Effects of job-based psychological ownership on territoriality, information exchange, and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 108, 403–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Peterson, R., Phillips, D. J., Podolny, J., & Ridgeway, C. L. (2012). Introduction to the special issue: Bringing status to the table—Attaining, maintaining, and experiencing status in organizations and markets. Organization Science, 23, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B., Xia, T. T., & Luo, W. H. (2023). How does team territorial behavior reduce team innovation efficiency: The mediating role of team knowledge hiding and the moderating role of ethical leadership. Management Review, (3), 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., Foulsham, T., Kingstone, A., & Henrich, J. (2013). Two ways to the top: Evidence that dominance and prestige are distinct yet viable avenues to social rank and influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. B., Tran, T. B. H., & Kang, S. (2017). Inclusive leadership and employee well-being: The mediating role of person–job fit. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J. F., & Richter, A. W. (2006). Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: Development and application of a slope difference test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z. H., & Xiang, Q. Y. (2022). A study on the buffering mechanism of individual resilience on the relationship between workplace exclusion and territorial behavior. Leadership Science, 38(10), 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwertmann, D. J. G., & Boehm, S. A. (2016). Status matters: The asymmetric effects of supervisor–subordinate disability incongruence and climate for inclusion. Academy of Management Journal, 59, 44–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, R., Zigarmi, D., & Richardson, A. (2019). Leadership behavior: A partial test of the employee work passion model. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 30, 311–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, A., & Kurer, T. (2022). Automation, digitalization, and artificial intelligence in the workplace: Implications for political behavior. Annual Review of Political Science, 25, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J. M., & Zhou, J. (2002). Understanding when bad moods foster creativity and good ones don’t: The role of context and clarity of feelings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R. P., Gong, R., Wei, J., & Wang, K. C. (2024). Inclusive leadership and employees’ tacit knowledge sharing: A cognitive-emotional personality systems theory-based perspective. Science of Science and Management of S. & T., 46, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, P., He, W., & Long, L. (2018). Why and when empowering leadership has different effects on employee work performance: The pivotal roles of passion for work and role breadth self-efficacy. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 25, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, V. T., & Astakhova, M. N. (2018). Disentangling passion and engagement: An examination of how and when passionate employees become engaged ones. Human Relations, 71, 973–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, V. T., Kong, D. T., Lee, C., Dubreuil, P., & Forest, J. (2018). Promoting harmonious work passion among unmotivated employees: A two-nation investigation of the compensatory function of cooperative psychological climate. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 106, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., & Tang, C. Y. (2020). Exploitative leadership and territorial behavior: Conditional process analysis. Chinese Journal of Management, 17(10), 1489–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundschell, A., Backmann, J., Tian, A. W., & Hoegl, M. (2025). Leader inclusiveness and team resilience capacity in multinational teams: The role of organizational diversity climate. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 46, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, W. S., Otten, S., van der Zee, K. I., & Jans, L. (2014). Inclusion: Conceptualization and measurement. European Journal of Social Psychology, 44, 370–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R., Hu, W., & Li, S. (2022). Ambidextrous leadership and organizational innovation: The importance of knowledge search and strategic flexibility. Journal of Knowledge Management, 26, 781–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J., Ding, W., Wang, R., & Li, S. (2022). Inclusive leadership and employees’ voice behavior: A moderated mediation model. Current Psychology, 41, 6395–6405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y. J., Zhang, L. Y., Huang, Q., & Jiang, C. Y. (2017). A literature review of work passion and prospects. Foreign Economics & Management, 39(8), 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, S. R., Zada, M., Nouman, M., Rahman, S. U., Fayaz, M., Ullah, R., Salazar-Sepúlveda, G., Vega-Muñoz, A., & Contreras-Barraza, N. (2022). Investigating inclusive leadership and pro-social rule breaking in hospitality industry: Important role of psychological safety and leadership identification. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 8291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, L., Li, X. Y., & Zhang, F. W. (2020). The influence of inclusive leadership on employees’ proactive behavior: The mediating effects of organizational-based self-esteem and error management climate. Management Review, 32(2), 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavigne, G. L., Forest, J., & Crevier-Braud, L. (2012). Passion at work and burnout: A two-study test of the mediating role of flow experiences. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 21, 518–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Y., & Tang, N. Y. (2025). Review and perspectives in inclusive leadership: Based on bibliometric methods. Management Review, 37(2), 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D., Chen, X., & Yao, X. (2011). From autonomy to creativity: A multilevel investigation of the mediating role of harmonious passion. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z. Q., Deng, C. J., Liao, J. Q., & Long, L. R. (2013). Status-striving motivation, criteria for status promotion, and employees’ innovative behavior choice. China Industrial Economics, 31(10), 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E. A., & Bandura, A. (1987). Social foundations of thought and action: A social-cognitive view. The Academy of Management Review, 12, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L., & Ma, K. Y. (2021). Research on the relationship between dual work passion and work well-being of knowledge workers: Based on work-family conflict perspective. East China Economic Management, 35(1), 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, A., Rafique, M., & Mubarak, N. (2021). Impact of inclusive leadership on project success. International Journal of Information Technology Project Management, 12, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, B. A., Wolfe, M. T., & Syed, I. (2017). Passion and grit: An exploration of the pathways leading to venture success. Journal of Business Venturing, 32, 260–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishii, L. H. (2013). The benefits of climate for inclusion for gender-diverse groups. Academy of Management Journal, 56, 1754–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishii, L. H., & Mayer, D. M. (2009). Do inclusive leaders help to reduce turnover in diverse groups? The moderating role of leader–member exchange in the diversity to turnover relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 1412–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offermann, L. R., & Basford, T. E. (2013). Inclusive human resource management. In Diversity at work: The practice of inclusion. Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrewé, P. L., Hochwarter, W. A., Ferris, G. R., McAllister, C. P., & Harris, J. N. (2014). Developing a passion for work passion: Future directions on an emerging construct. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, F. L., Vallerand, R. J., & Lavigne, G. L. (2009). Passion does make a difference in people’s lives: A look at well-being in passionate and non-passionate individuals. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 1, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L., Liu, B., Wei, X., & Hu, Y. (2019). Impact of inclusive leadership on employee innovative behavior: Perceived organizational support as a mediator. PLoS ONE, 14, e0212091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randel, A. E., Galvin, B. M., Shore, L. M., Ehrhart, K. H., Chung, B. G., Dean, M. A., & Kedharnath, U. (2018). Inclusive leadership: Realizing positive outcomes through belongingness and being valued for uniqueness. Human Resource Management Review, 28, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A., Owens, B., Yam, K. C., Bluhm, D., Cunha, M. P. E., Silard, A., Gonçalves, L., Martins, M., Simpson, A. V., & Liu, W. (2019). Leader humility and team performance: Exploring the mediating mechanisms of team PsyCap and task allocation effectiveness. Journal of Management, 45, 1009–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosing, K., Frese, M., & Bausch, A. (2011). Explaining the heterogeneity of the leadership-innovation relationship: Ambidextrous leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 22, 956–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, L. M., Randel, A. E., Chung, B. G., Dean, M. A., Holcombe Ehrhart, K., & Singh, G. (2011). Inclusion and diversity in work groups: A review and model for future research. Journal of Management, 37, 1262–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slemp, G. R., Zhao, Y., Hou, H., & Vallerand, R. J. (2021). Job crafting, leader autonomy support, and passion for work: Testing a model in Australia and China. Motivation and Emotion, 45, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T., Zeng, X. Y., Ma, W. C., & Wu, X. J. (2023). A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of inclusive leadership in the Chinese context. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, 37(5), 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z. H., & Yuan, L. (2024). Why not share good ideas? The effect of leaders’ bottom-line mentality on the employees’ creative territory behavior. Science & Technology Progress and Policy, 41(1), 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N. Y., & Zhang, K. L. (2015). Inclusive leadership: Review and prospects. Chinese Journal of Management, 12(6), 932–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R. J., Blanchard, C., Mageau, G. A., Koestner, R., Ratelle, C., Léonard, M., Gagné, M., & Marsolais, J. (2003). Les passions de l’âme: On obsessive and harmonious passion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallerand, R. J., Houlfort, N., & Bourdeau, S. (2019). Passion for work. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R. J., Salvy, S., Mageau, G. A., Elliot, A. J., Denis, P. L., Grouzet, F. M. E., & Blanchard, C. (2007). On the role of passion in performance. Journal of Personality, 75, 505–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B. C., He, M. M., & Zhao, J. Y. (2025). Impact of job autonomy on business model innovation in the digital era. Journal of Statistics and Information, 40(1), 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Qian, Z., & Ouyang, L. (2022). “One glories, all glory”: Role of inclusiveness behavior in creativity. Current Psychology, 41, 8449–8460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. Y., Zhang, W. J., Chen, G., & Liu, F. (2016). “I am,” “I can,” “I do”—The influence path between work passion and employee creativity. Human Resources Development of China, 16(22), 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z. C., Wang, H., Wang, K. W., & Cui, M. J. (2022). The developmental logic of knowledge hiding: A literature review. Science & Technology Progress and Policy, 39(18), 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W. J., Feng, J. M., Lin, Y. X., & Zhao, X. (2021). The dynamic effect and mechanism of commuting recovery activities on work passion. Advances in Psychological Science, 29(4), 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. F., Xi, M., & Zhao, S. M. (2021). The effect of inclusive leadership on follower proactive behavior: The social influence theory perspective. Management Review, 33(6), 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G., & Xiao, S. H. (2025). How platform leadership inspires breakthrough innovation behaviors of knowledge workers: A moderated chain mediation model. Science & Technology Progress and Policy, 42(6), 130–140. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y., Yuan, L., Ye, L., & Yang, S. (2025). How Does Work Passion Affect Employees’ Radical and Incremental Creativity?——A Three-way Interaction Model. Journal of Business Research, 196, 115430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M. A., & Sharma, G. (2019). The relationship between faculty members’ passion for work and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20, 863–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. C., & Ling, W. Q. (2016). The influence of temporal leadership on employee’s helping behavior: The effect of passion and proactive personality. Journal of Psychological Science, 39(4), 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. L., Yuan, Y. W., & Liu, J. (2017). Organizational territoriality: Literature review and research prospects. Science & Technology Progress and Policy, 34(24), 154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, F. Q., Lu, Q., & Chen, Y. (2020). A research on the impact of inclusive human resource practice on individual creativity: The effect of ambidextrous learning and charismatic leadership. Science Research Management, 41(4), 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X. T., Yang, X., Diaz, I., & Yu, M. (2018). Is too much inclusive leadership a good thing? An examination of the curvilinear relationship between inclusive leadership and employees’ task performance. International Journal of Manpower, 39, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J., Deng, J., & Luo, J. L. (2018). The effect of inclusive leadership on team performance and employee innovative performance: A moderated mediation model. Science of Science and Management of S&T, 39(9), 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, X., Fu, Y., & Wang, T. (2019). Inclusive leadership, perceived insider status and employee knowledge sharing: Moderating role of organizational innovation climate. R&D Management, 31(3), 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X., Wang, T., & Fu, Y. (2020). A research on the relationship between perceived insider status and knowledge sharing. Science Research Management, 41(7), 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q. X. (2011). Analysis of the realization path of “inclusive growth”—Based on the perspective of “inclusive leadership”. Forward Position, 18(23), 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X., Jiang, F., Volpone, S. D., Baldridge, D. C., & Li, R. (2025). The role of inclusive leadership in reducing disability accommodation request withholding. Journal of Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigarmi, D., Galloway, F. J., & Roberts, T. P. (2018). Work locus of control, motivational regulation, employee work passion, and work intentions: An empirical investigation of an appraisal model. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigarmi, D., Nimon, K., Houson, D., Witt, D., & Diehl, J. (2011). A preliminary field test of an employee work passion model. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 22, 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic model: A, B, C, D | 406.290 | 371 *** | 1.095 | 0.021 | 0.040 | 0.992 | 0.991 |

| Three-factor model: A, B, C+D | 791.684 | 374 *** | 2.117 | 0.070 | 0.096 | 0.906 | 0.898 |

| Bi-factor model: A, B+C+D | 1350.398 | 376 *** | 3.591 | 0.107 | 0.128 | 0.781 | 0.723 |

| One-factor model: A+B+C+D | 2470.652 | 377 *** | 6.553 | 0.157 | 0.157 | 0.529 | 0.493 |

| Variable | M | SD | AVE | CR | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Inclusive leadership | 0.507 | 0.501 | 0.670 | 0.948 | 1 | |||

| 2. Work autonomy | 0.502 | 0.501 | 0.548 | 0.894 | 0.004 | 1 | ||

| 3. Creative territory behavior | 3.423 | 1.162 | 0.618 | 0.866 | −0.337 ** | −0.296 ** | 1 | |

| 4. Harmonious work passion | 3.632 | 1.019 | 0.649 | 0.943 | 0.362 ** | 0.317 ** | −0.454 ** | 1 |

| Variable | Work Autonomy | Harmonious Work Passion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | |

| Constant | 4.287 ** | 5.412 *** | 5.425 ** | 2.682 ** |

| Gender | −0.290 | −0.113 | −0.142 | 0.277 * |

| Age | −0.027 | 0.011 | −0.004 | 0.054 |

| Inclusive leadership | −0.787 ** | −0.472 ** | 0.743 ** | |

| Harmonious work passion | −0.511 *** | −0.424 ** | ||

| F | 10.792 *** | 19.582 *** | 17.937 *** | 13.288 *** |

| R2 | 0.127 | 0.547 | 0.244 | 0.152 |

| ΔR2 | 0.115 | 0.197 | 0.231 | 0.140 |

| Moderator Variable | Level | Indirect Mediating Effect | SE | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | ||||

| Work autonomy | high | −0.467 | 0.107 | −0.0.685 | −0.274 |

| difference value | −0.304 | 0.120 | −0.574 | −0.095 | |

| low | −0.162 | 0.080 | −0.326 | −0.009 | |

| Control Variable | Option | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| gender | man | 243 | 52.71 |

| woman | 218 | 47.29 | |

| age | 25 and younger | 153 | 33.19 |

| 26–30 | 192 | 41.65 | |

| 31–35 | 40 | 8.68 | |

| 36–40 | 58 | 12.58 | |

| 41 years and older | 18 | 3.90 | |

| education background | high school and below | 27 | 5.86 |

| junior college | 87 | 18.87 | |

| regular college course | 234 | 50.76 | |

| graduate student | 113 | 24.51 | |

| position | clerk | 361 | 78.31 |

| lower management | 73 | 15.84 | |

| middle management | 22 | 4.77 | |

| top management | 5 | 1.08 | |

| tenure | 1 year and below | 135 | 29.28 |

| 2–3 | 127 | 27.55 | |

| 4–5 | 112 | 24.30 | |

| 6–9 | 56 | 12.15 | |

| more than 10 years | 31 | 6.72 | |

| industry | communication | 69 | 14.97 |

| IT | 138 | 29.93 | |

| manufacturing industry | 116 | 25.16 | |

| bioengineering | 23 | 4.99 | |

| space flight and aviation | 16 | 3.47 | |

| energy | 69 | 14.97 | |

| financial | 30 | 6.51 | |

| total | 461 | 100.00 | |

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic model: A, B, C, D, E | 1328.630 *** | 979 | 1.357 | 0.028 | 0.032 | 0.975 | 0.974 |

| Quartet model: A, B, C, D+E | 3722.482 *** | 983 | 3.787 | 0.078 | 0.093 | 0.808 | 0.798 |

| Three-factor model: A+B, C, D+E | 4431.831 *** | 986 | 4.495 | 0.087 | 0.114 | 0.758 | 0.746 |

| Bi-factor model: A+B+C, D+E | 5634.658 *** | 988 | 5.703 | 0.101 | 0.131 | 0.674 | 0.659 |

| One-factor model: A+B+C+D+E | 7702.577 *** | 989 | 7.788 | 0.121 | 0.138 | 0.529 | 0.507 |

| Variable | M | SD | AVE | CR | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. gender | 1.47 | 0.50 | - | - | 1 | ||||||||||

| 2. age | 2.12 | 1.12 | - | - | 0.062 | 1 | |||||||||

| 3. education background | 2.94 | 0.82 | - | - | 0.012 | 0.091 | 1 | ||||||||

| 4. position | 1.29 | 0.60 | - | - | 0.011 | 0.755 ** | 0.009 | 1 | |||||||

| 5. tenure | 2.39 | 1.21 | - | - | 0.114 * | 0.820 ** | −0.191 ** | 0.633 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 6. industry | 3.23 | 1.85 | - | - | −0.052 | −0.017 | 0.044 | 0.011 | −0.090 | 1 | |||||

| 7. A | 3.72 | 1.00 | 0.606 | 0.933 | 0.016 | −0.102 * | 0.124 ** | −0.043 | −0.110 * | 0.055 | 1 | ||||

| 8. B | 3.65 | 1.12 | 0.639 | 0.876 | 0.020 | 0.178 ** | −0.080 | 0.101 * | 0.207 ** | 0.001 | −0.494 ** | 1 | |||

| 9. C | 3.55 | 1.01 | 0.553 | 0.896 | 0.003 | −0.004 | 0.078 | 0.013 | −0.065 | 0.062 | 0.382 ** | −0.451 ** | 1 | ||

| 10. D | 3.41 | 1.08 | 0.658 | 0.945 | −0.009 | −0.026 | 0.071 | 0.020 | −0.093 * | 0.086 | 0.322 ** | −0.500 ** | 0.446 ** | 1 | |

| 11. E | 3.78 | 0.94 | 0.568 | 0.957 | −0.007 | −0.055 | 0.047 | −0.022 | −0.062 | 0.041 | 0.298 ** | −0.461 ** | 0.420 ** | 0.464 ** | 1 |

| Variable | Creative Territory Behavior | Harmonious Work Passion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | M9 | |

| gender | −0.002 | 0.010 | 0.012 | 0.017 | 0.008 |

| age | 0.136 | 0.029 | 0.081 | 0.083 | 0.168 |

| education background | −0.065 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.039 | −0.018 |

| position | −0.092 | −0.046 | −0.043 | 0.047 | 0.010 |

| tenure | 0.143 | 0.163 * | 0.111 | −0.153 | −0.169 |

| industry | 0.019 | 0.043 | 0.052 | 0.049 | 0.030 |

| inclusive leadership | −0.478 *** | −0.361 *** | 0.381 *** | ||

| harmonious work passion | −0.308 *** | ||||

| F | 3.956 *** | 23.999 *** | 30.529 *** | 1.267 | 12.005 *** |

| R2 | 0.050 | 0.271 | 0.351 | 0.016 | 0.156 |

| ΔR2 | 0.050 | 0.221 | 0.080 | 0.016 | 0.140 |

| Effect Value | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | Relative Effect Value (Proportion of Effect) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| total effect | −5.336 | 0.456 | −6.232 | −4.441 | |

| direct effect | −4.026 | 0.456 | −4.939 | −3.112 | 75.45% |

| mediating effect of harmonious work passion | −1.311 | 0.2221 | −1.772 | −0.0909 | 24.57% |

| Variable | Harmonious Work Passion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M10 | M11 | M12 | M13 | |

| gender | 0.017 | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.005 |

| age | 0.083 | 0.144 | 0.151 | 0.144 |

| education background | 0.039 | −0.015 | −0.037 | −0.043 |

| position | 0.047 | −0.013 | −0.026 | −0.009 |

| tenure | −0.153 | −0.114 | −0.120 | −0.130 |

| industry | 0.049 | 0.011 | −0.005 | −0.005 |

| inclusive leadership | 0.232 *** | 0.257 *** | 0.205 *** | |

| work autonomy | 0.256 *** | 0.242 *** | 0.207 *** | |

| status competition motivation | 0.233 *** | 0.273 *** | 0.270 *** | |

| inclusive leadership × work autonomy | 0.159 *** | 0.161 *** | ||

| inclusive leadership×status competition motivation | 0.070 | 0.133 ** | ||

| work autonomy × status competition motivation | 0.043 | 0.063 | ||

| inclusive leadership × work autonomy × status competition motivation | 0.166 *** | |||

| F | 10,267 | 22.187 *** | 20.142 *** | 19.858 *** |

| R2 | 0.016 | 0.307 | 0.350 | 0.366 |

| ΔR2 | 0.016 | 0.041 | 0.001 | 0.016 |

| Moderator Variable | Level | Indirect Mediating Effect | SE | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | ||||

| work autonomy | high | −0.1740 | 0.0294 | −0.2342 | −0.1205 |

| difference value | −0.1423 | 0.0344 | −0.2126 | −0.0771 | |

| low | −0.0317 | 0.0228 | −0.0775 | 0.0127 | |

| Work Autonomy | Status Competition Motivation | Indirect Mediating Effect | SE | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | ||||

| 2.3275 | 2.8393 | −0.00156 | 0.0240 | −0.0625 | 0.0314 |

| 2.3275 | 4.7210 | −0.0084 | 0.0389 | −0.0899 | 0.0651 |

| 4.4939 | 2.8393 | −0.0314 | 0.0476 | −0.1158 | −0.0721 |

| 4.4939 | 4.7210 | −0.2269 | 0.0390 | −0.3079 | −0.1528 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, G.; Zhang, Z. Inclusive Leadership and Creative Territory Behavior: A Triple Interactive Moderating Effect Model. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081105

Shi G, Zhang Z. Inclusive Leadership and Creative Territory Behavior: A Triple Interactive Moderating Effect Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081105

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Guanfeng, and Ziyi Zhang. 2025. "Inclusive Leadership and Creative Territory Behavior: A Triple Interactive Moderating Effect Model" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081105

APA StyleShi, G., & Zhang, Z. (2025). Inclusive Leadership and Creative Territory Behavior: A Triple Interactive Moderating Effect Model. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081105