Do Social Relationships Influence Moral Judgment? A Cross-Cultural Examination

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Moral Judgment and Relationship Regulation Theory

2.2. Cultural Differences Between the East and the West

3. Study 1

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Materials and Procedure

Relational Contexts

Moral Judgment

3.1.3. Data Analysis

3.2. Results

Moral Judgment

4. Study 2

4.1. Methods

4.1.1. Participants

4.1.2. Materials and Procedure

4.1.3. Data Analysis

4.2. Results

5. Study 3

5.1. Methods

5.1.1. Participants

5.1.2. Materials and Procedure

5.1.3. Data Analysis

5.2. Results

Moral Judgment

6. Discussion

6.1. The Relationship Between Social Relationships and Moral Judgment

6.2. Cultural Variation in Social Relationships and Moral Judgment

6.3. Practical Implications

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alicke, M. D., Mandel, D. R., Hilton, D. J., Gerstenberg, T., & Lagnado, D. A. (2015). Causal conceptions in social explanation and moral evaluation: A historical tour. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(6), 790–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atari, M., Lai, M. H. C., & Dehghani, M. (2020). Sex differences in moral judgments across 67 countries. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 287(1934), 20201201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentahila, L., Fontaine, R., & Pennequin, V. (2021). Universality and cultural diversity in moral reasoning and judgment. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 764360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchtel, E. E., Guan, Y., Peng, Q., Su, Y., Sang, B., Chen, S. X., & Bond, M. H. (2015). Immorality east and west: Are immoral behaviors especially harmful, or especially uncivilized? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(10), 1382–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchtel, E. E., Ng, L. C. Y., Norenzayan, A., Heine, S. J., Biesanz, J. C., Chen, S. X., Bond, M. H., Peng, Q., & Su, Y. (2018). A sense of obligation: Cultural differences in the experience of obligation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(11), 1545–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Lu, J., Walker, D. I., Ma, W., Glenn, A. L., & Han, H. (2025). Perceived stress and society-wide moral judgment. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(6), 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen-Xia, X. J., Betancor, V., Rodríguez-Gómez, L., & Rodríguez-Pérez, A. (2023). Cultural variations in perceptions and reactions to social norm transgressions: A comparative study. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1243955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A. B. (2009). Many forms of culture. American Psychologist, 64(3), 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahò, M. (2025). Emotional responses in clinical ethics consultation decision-making: An exploratory study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, L. (2010). Humanity, obligation, and the good will: An argument against Dean’s interpretation of humanity. Kantian Review, 15(1), 118–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeScioli, P. (2023). The dangers of alliances caused the evolution of moral principles. Psychological Inquiry, 34(3), 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M., Jurgens, D., Banea, C., & Mihalcea, R. (2019). Perceptions of social roles across cultures. In Social informatics: Lecture notes in computer science (pp. 157–172). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Dricu, M., & Frühholz, S. (2020). A neurocognitive model of perceptual decision-making on emotional signals. Human Brain Mapping, 41(6), 1532–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earp, B. D., Calcott, R., Reinecke, M. G., & Clark, M. S. (2021). How social relationships shape moral wrongness judgments. Nature Communications, 12, 5775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellemers, N. (2017). Morality and the regulation of social behavior: Groups as moral anchors. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, A. P. (1991). Structures of social life: The four elementary forms of human relations—Communal sharing, authority ranking, equality matching, market pricing. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, A. P. (1992). The four elementary forms of sociality: Framework for a unified theory of social relations. Psychological Review, 99(4), 689–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, G., Kincannon, H. T., Poston, D. L., Jr., & Walther, C. S. (2013). Patterns of sexual activity in China and the United States. In D. L. Poston Jr., & C. S. Walther (Eds.), The family and social change in Chinese societies (pp. 99–116). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand, M. J., Raver, J. L., Nishii, L., Leslie, L. M., Lun, J., Lim, B. C., Duan, L., Almaliach, A., Ang, S., Arnadottir, J., Aycan, Z., Boehnke, K., Boski, P., Cabecinhas, R., Chan, D., Chhokar, J., D’Amato, A., Ferrer, M. S., Fischlmayr, I. C., … Yamaguchi, S. (2011). Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. Science, 332(6033), 1100–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J., Haidt, J., & Nosek, B. A. (2009). Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 1029–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J., Nosek, B. A., Haidt, J., Iyer, R., Koleva, S., & Ditto, P. H. (2011). Mapping the moral domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 366–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, K., Young, L., & Waytz, A. (2012). Mind perception is the essence of morality. Psychological Inquiry, 23(2), 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, J. D. (2014). Moral tribes: Emotion, reason, and the gap between us and them. Penguin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, J. D., Sommerville, R. B., Nystrom, L. E., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science, 293(5537), 2105–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guglielmo, S. (2015). Moral judgment as information processing: An integrative review. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108(4), 814–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J., Koller, S. H., & Dias, M. G. (1993). Affect, culture, and morality, or is it wrong to eat your dog? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(4), 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, A. C. (2021). Derogation of promiscuity. In T. K. Shackelford, & V. A. Weekes-Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of evolutionary psychological science (pp. 1912–1914). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, K. K. (2012). Foundations of Chinese psychology: Confucian social relations. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, W. Y., & Peng, M. (2021). The effects of social perception on moral judgment. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 557216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. (2011). Diasporic dreams, middle-class moralities and migrant domestic workers among Muslim Filipinos in Saudi Arabia. In P. Werbner, & M. Johnson (Eds.), Diasporic journeys, ritual, and normativity among Asian migrant women (pp. 224–244). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, J. (2007). Taking the first step toward a moral action: A review of moral sensitivity measurement across domains. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 168(3), 323–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsarov, J. (2023). Moral sensitivity. In S. T. Allison, G. R. Goethals, & R. M. Kramer (Eds.), Encyclopedia of heroism studies (pp. 1–9). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lemay, E. P., Jr., Teneva, N., & Xiao, Z. (2025). Interpersonal emotion regulation as a source of positive relationship perceptions: The role of emotion regulation dependence. Emotion, 25(2), 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marples, R. (2022). Moral sensitivity: The central question of moral education. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 56(2), 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquette, T. (2020, June 28). Family first: Good Samaritans viewed unfavorably if they help strangers over loved ones. Study Finds. [Google Scholar]

- Mascolo, M. F., Fasoli, A. D., & Greenway, D. (2021). A relational approach to moral development in societies, organizations and individuals. Integral Review, 17(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo, A., & Brown, C. M. (2022). Culture points the moral compass: Shared basis of culture and morality. Culture and Brain, 10, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, R. M., Mason, J. E., & Young, L. (2021). Re-examining the role of family relationships in structuring perceived helping obligations, and their impact on moral evaluation. The Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 96, 104–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, M., Khosravi, Z., Noaparast, K. B., & Sabramiz, A. (2021). Moral judgment and decision-making based on interpersonal relationships with relatives and non-relatives: A systematic review. Advances in Cognitive Sciences, 23(1), 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Niven, K., & López-Pérez, B. (2025). Interpersonal emotion regulation: Reflecting on progress and charting the path forward. Emotion, 25(2), 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128(1), 3–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, T. S., & Fiske, A. P. (2011). Moral psychology is relationship regulation: Moral motives for unity, hierarchy, equality, and proportionality. Psychological Review, 118(1), 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, T. S., & Fiske, A. P. (2012). Beyond harm, intention, and dyads: Relationship regulation, virtuous violence, and metarelational morality. Psychological Inquiry, 23(2), 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reader, W., & Hughes, S. (2020). The evolution and function of third-party moral judgment. In L. Workman, W. Reader, & J. H. Barkow (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of evolutionary perspectives on human behavior (pp. 105–157). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shweder, R. A. (1997). The surprise of ethnography. Ethos, 25(2), 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, A., Laham, S. M., & Fiske, A. P. (2016). Wrongness in different relationships: Relational context effects on moral judgment. The Journal of Social Psychology, 156(5), 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, W. C., Morelli, S. A., Ong, D. C., & Zaki, J. (2018). Interpersonal emotion regulation: Implications for affiliation, perceived support, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 115(2), 224–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlodarski, R., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2015). Do you stray or stay? Evidence for alternating mating strategy phenotypes in both men and women. Biology Letters, 11(2), 20140909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F., Peng, K. P., Han, T. T., Chai, F. Y., & Bai, Y. (2011). Dilemma of moral dilemmas: The conflict between emotion and reasoning in moral judgments. Advanced Psychological Science, 19(11), 1702–1712. [Google Scholar]

- Zakharin, M., & Bates, T. C. (2023). Relational models theory: Validation and replication for four fundamental relationships. PLoS ONE, 18(6), e0287391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

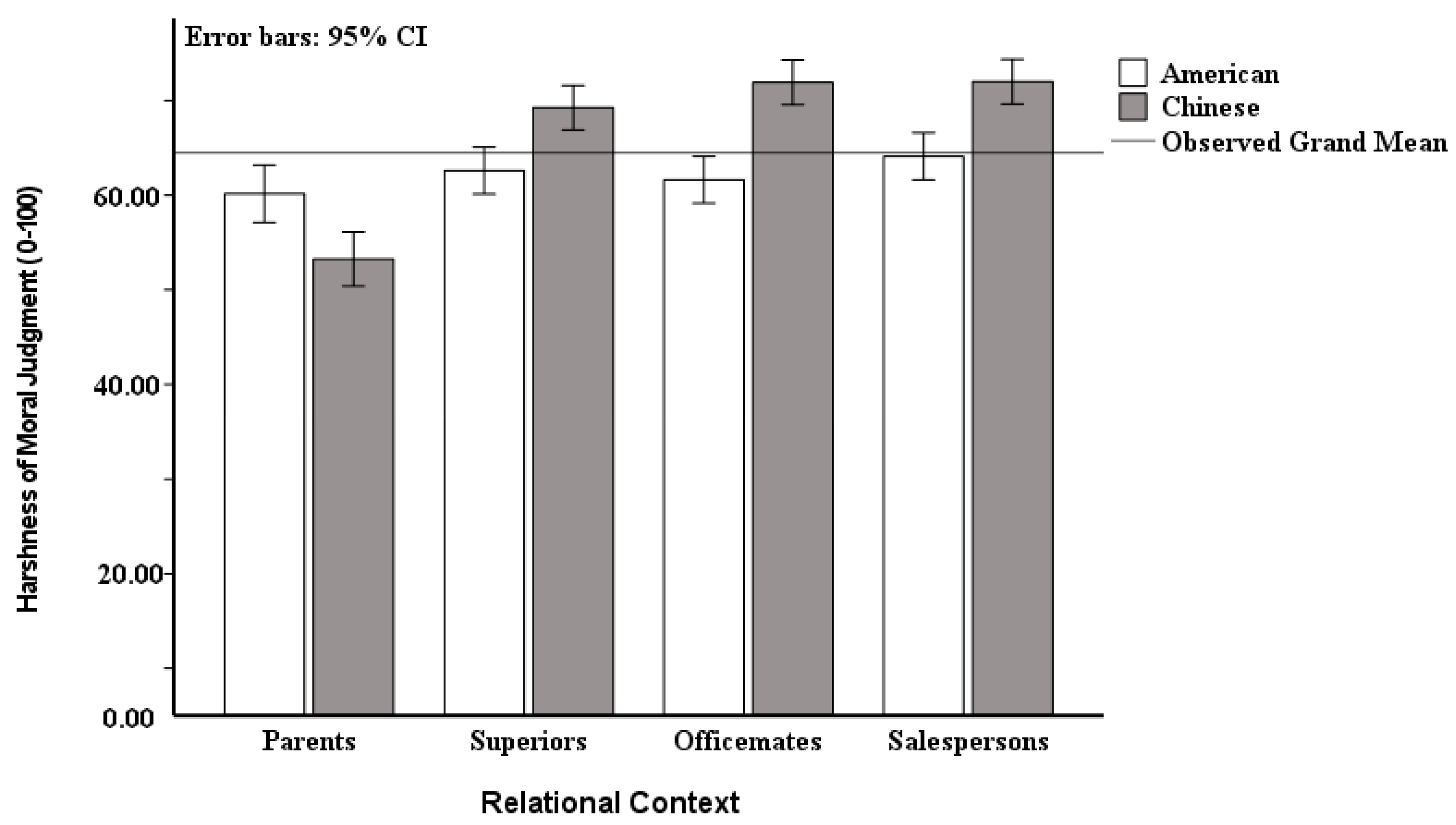

| Social Relationship | Moral Judgements | |

|---|---|---|

| M | SD | |

| Parents | 4.86 | 0.99 |

| Superiors | 5.25 | 1.17 |

| Colleagues | 5.06 | 1.12 |

| Salesperson | 5.50 | 0.97 |

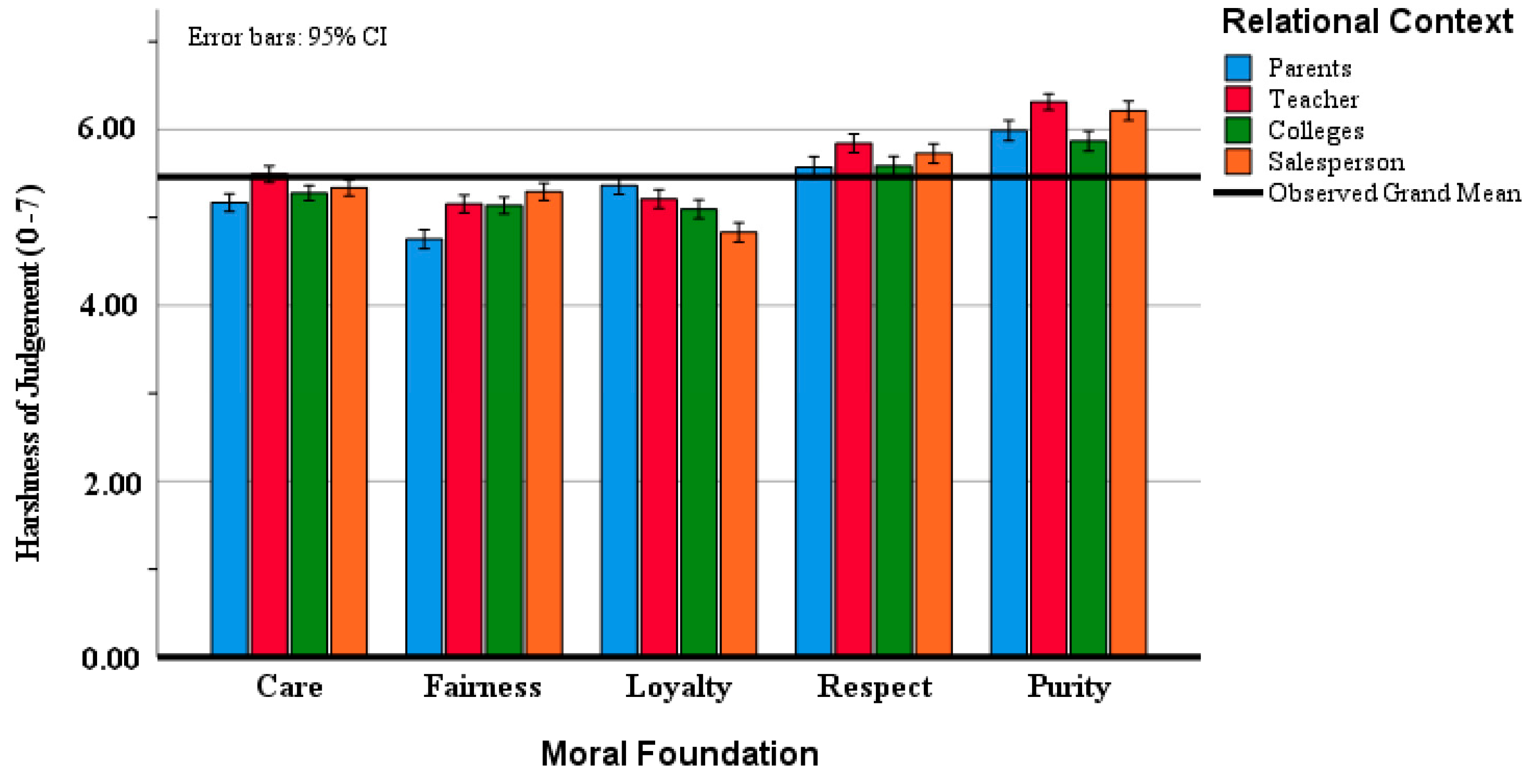

| Moral Foundation Being Violated | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relational Context | Care | Fairness | Loyalty | Respect | Purity |

| M (SD) | |||||

| Parents | 5.17 (0.74) | 4.76 (0.78) | 5.36 (0.74) | 5.57 (0.89) | 5.99 (0.84) |

| Teacher | 5.49 (0.68) | 5.15 (0.74) | 5.21 (0.78) | 5.84 (0.78) | 6.31 (0.67) |

| Colleagues | 5.28 (0.63) | 5.14 (0.70) | 5.11 (0.77) | 5.60 (0.80) | 5.88 (0.83) |

| Salesperson | 5.34 (0.66) | 5.29 (0.71) | 4.83 (0.80) | 5.73 (0.81) | 6.21 (0.80) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ding, L.; Fu, L.; Li, K.; Yu, F. Do Social Relationships Influence Moral Judgment? A Cross-Cultural Examination. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081097

Ding L, Fu L, Li K, Yu F. Do Social Relationships Influence Moral Judgment? A Cross-Cultural Examination. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081097

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Lina, Lei Fu, Kai Li, and Feng Yu. 2025. "Do Social Relationships Influence Moral Judgment? A Cross-Cultural Examination" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081097

APA StyleDing, L., Fu, L., Li, K., & Yu, F. (2025). Do Social Relationships Influence Moral Judgment? A Cross-Cultural Examination. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081097