Perceived Public Stigma Toward Psychological Help: Psychometric Validation of the Stigma Scale for Receiving Psychological Help Among Chinese Law Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Stigma Scale for Receiving Psychological Help (SSRPH)

2.2.2. Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help–Short Form (ATSPPH-SF)

2.2.3. Sociodemographic Characteristics

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

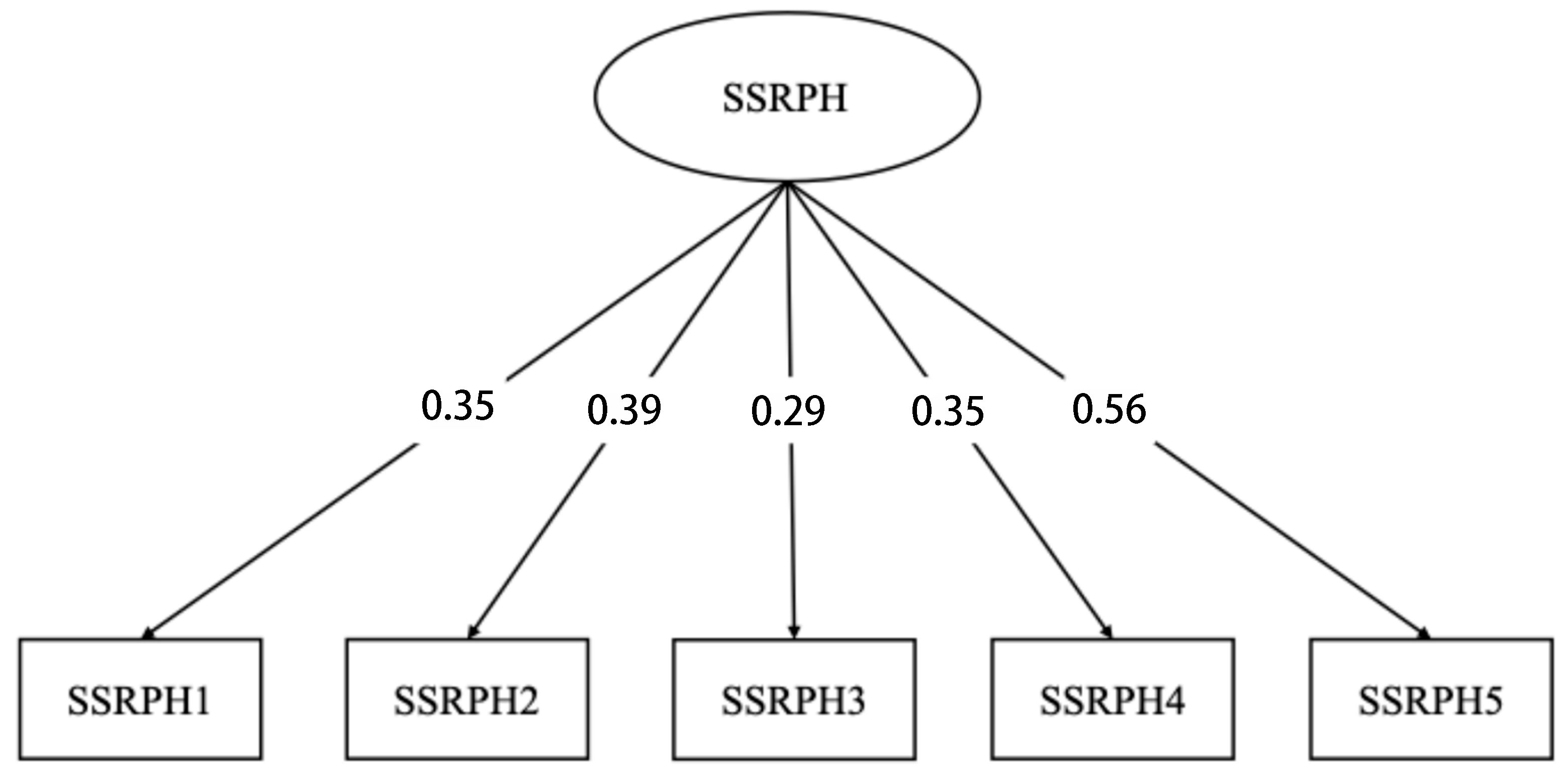

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

3.3. Internal Consistency and Discriminant Validity

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of Findings

4.2. Theoretical Contributions

4.3. Practical Implications

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EFA | Exploratory factor analysis |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| SSRPH | Stigma Scale for Receiving Psychological Help |

| ATSPPH-SF | Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help–Short Form |

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibelhausen, J., Bender, K. M., & Barrett, R. (2015). Reducing the stigma: The deadly effect of untreated mental illness and new strategies for changing outcomes in law students. William Mitchell Law Review, 41(3), 7. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford publications. [Google Scholar]

- Büchter, R. B., & Messer, M. (2017). Interventions for reducing self-stigma in people with mental illnesses: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. German Medical Science: GMS e-Journal, 15, Doc07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheang, S. I., & Davis, J. M. (2014). Influences of face, stigma, and psychological symptoms on help-seeking attitudes in Macao. PsyCh Journal, 3(3), 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. (2018). Some people may need it, but not me, not now: Seeking professional help for mental health problems in urban China. Transcultural Psychiatry, 55(6), 754–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P. W., & Rao, D. (2012). On the self-stigma of mental illness: Stages, disclosure, and strategies for change. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry/La Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 57(8), 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P. W., & Watson, A. C. (2002). Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry, 1(1), 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment Research & Evaluation, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dubreucq, J., Plasse, J., & Franck, N. (2021). Self-stigma in serious mental illness: A systematic review of frequency, correlates, and consequences. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 47(5), 1261–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J. D., Schweinle, W., & Anderson, S. M. (2008). Reliability and validity of the attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help scale-short form. Psychiatry Research, 159(3), 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, G. (2021). Law-students wellbeing and vulnerability. The Law Teacher, 56(1), 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E. H., & Farina, A. (1995). Attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help: A shortened form and considerations for research. Journal of College Student Development, 36(4), 368–373. [Google Scholar]

- Fortner, N. C. (2022). Mental health, law school, and bar admissions: Eliminating stigma and fostering a healthier profession. Arkansas Law Review, 75(3), 689–711. [Google Scholar]

- Gearing, R. E., Brewer, K. B., Leung, P., Cheung, M., Chen, W., Carr, L. C., Bjugstad, A., & He, X. (2024). Mental health help-seeking in China. Journal of Mental Health, 33(6), 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2009). Análise multivariada de dados (Multivariate data analysis) (6th ed.). Bookman. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 50(3), 337–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, H., Liu, Z., Yu, X., Yan, J., Yu, Y., Kou, C., Xu, X., Lu, J., Wang, Z., He, S., Xu, Y., He, Y., Li, T., Guo, W., Tian, H., Xu, G., Xu, X., … Wu, Y. (2019). Prevalence of mental disorders in China: A cross-sectional epidemiological study. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 6(3), 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. A., Kaniskan, B., & McCoach, D. B. (2015). The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociological Methods & Research, 44(3), 486–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications. [Google Scholar]

- Komiya, N., Good, G. E., & Sherrod, N. B. (2000). Emotional openness as a predictor of college students’ attitudes toward seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47(1), 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, C., Zhou, T., Bao, Y., Wang, R., Weng, X., Su, J., Li, Y., Qiao, P., & Guo, D. (2024). Adaptation and validation of learned helplessness scale in Chinese law school students. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 17, 1831–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logsdon, M. C., Usui, W. M., & Nering, M. (2009). Validation of Edinburgh postnatal depression scale for adolescent mothers. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 12, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, C. S., Knox, V. J., Gekoski, W. L., & Macaulay, H. L. (2004). An adaptation and extension of the attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help scale. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(11), 2410–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, J. M., Jaffe, D. B., & Bender, K. M. (2016). Suffering in silence: The survey of law student well-being and the reluctance of law students to seek help for substance use and mental health concerns. Journal of Legal Education, 66(1), 116–156. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, G., Gladstone, G., & Chee, K. T. (2001). Depression in the planet’s largest ethnic group: The Chinese. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(6), 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M. D., Hickman, R. L., & Thomas, T. L. (2015). Stigma Scale for Receiving Psychological Help (SSRPH): An examination among adolescent girls. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 37(12), 1644–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, K., & Siller, N. (2024). From law school to practice: Conflict in Australian University mental health management and law student employability. International Journal of the Legal Profession, 31(1), 111–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmack, U. (2021). The implicit association test: A method in search of a construct. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(2), 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D. T. L., Li, X., Yu, L., Lin, L., & Chen, Y. (2022). Evaluation of electronic service-learning (e-service-learning) projects in mainland China under COVID-19. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 17(5), 3175–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W., Shen, Z., Wang, S., & Hall, B. J. (2020). Barriers to professional mental health help-seeking among Chinese adults: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J. R., Hammer, J. H., Vogel, D. L., Bitman, R. L., Wade, N. G., & Maier, E. J. (2013). Disentangling self-stigma: Are mental illness and help-seeking self-stigmas different? Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(4), 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, D. L., Strass, H. A., Heath, P. J., Al-Darmaki, F. R., Armstrong, P. I., Baptista, M. N., Brenner, R. E., Gonçalves, M., Lannin, D. G., Liao, H.-Y., Mackenzie, C. S., Mak, W. W. S., Rubin, M., Topkaya, N., Wade, N. G., Wang, Y.-F., & Zlati, A. (2017). Stigma of seeking psychological services: Examining college students across ten countries/regions. The Counseling Psychologist, 45(2), 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, D. L., Wade, N. G., & Haake, S. (2006). Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(3), 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, D. L., Wade, N. G., & Hackler, A. H. (2007). Perceived public stigma and the willingness to seek counseling: The mediating roles of self-stigma and attitudes toward counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(1), 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2022). WHO guidelines on mental health at work. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240053052 (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Yanos, P. T., Lucksted, A., Drapalski, A. L., Roe, D., & Lysaker, P. (2015). Interventions targeting mental health self-stigma: A review and comparison. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 38(2), 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H., Wardenaar, K. J., Xu, G., Tian, H., & Schoevers, R. A. (2020). Mental health stigma and mental health knowledge in Chinese population: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavrou, S., & Poulakis, M. (2017). Stigma and attitudes toward seeking counseling: A pilot study of cross-cultural differences between college students in the US and Cyprus. Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Education, 5(2), 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y., Lemmer, G., Xu, J., & Rief, W. (2019). Cross-cultural measurement invariance of scales assessing stigma and attitude to seeking professional psychological help. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwick, W. R., & Velicer, W. F. (1986). Comparison of five rules for determining the number of components to retain. Psychological Bulletin, 99(3), 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSRPH 1. Seeing a psychologist for emotional or interpersonal problems carries social stigma. | 1 | 0.59 | 0.69 | ||||

| SSRPH 2. It is a sign of personal weakness or inadequacy to see a psychologist for emotional or interpersonal problems. | 0.47 *** | 1 | 0.63 | 0.76 | |||

| SSRPH 3. People will see a person in a less favorable way if they come to know that he/she has seen a psychologist. | 0.45 *** | 0.69 *** | 1 | 0.69 | 0.74 | ||

| SSRPH 4. It is advisable for a person to hide from people that he/she has seen a psychologist. | 0.56 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.41 *** | 1 | 0.78 | 0.63 | |

| SSRPH 5. People tend to like less those who are receiving professional psychological help. | 0.38 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.33 *** | 1 | 0.45 | 0.49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, T.; Huang, Q.L.; Li, W. Perceived Public Stigma Toward Psychological Help: Psychometric Validation of the Stigma Scale for Receiving Psychological Help Among Chinese Law Students. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1084. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081084

Wang T, Huang QL, Li W. Perceived Public Stigma Toward Psychological Help: Psychometric Validation of the Stigma Scale for Receiving Psychological Help Among Chinese Law Students. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1084. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081084

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Tingting, Qi Lu Huang, and Wei Li. 2025. "Perceived Public Stigma Toward Psychological Help: Psychometric Validation of the Stigma Scale for Receiving Psychological Help Among Chinese Law Students" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1084. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081084

APA StyleWang, T., Huang, Q. L., & Li, W. (2025). Perceived Public Stigma Toward Psychological Help: Psychometric Validation of the Stigma Scale for Receiving Psychological Help Among Chinese Law Students. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1084. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081084