The Impact of School Burnout on Life Satisfaction Among University Students: The Mediating Effects of Loneliness and Fear of Alienation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. School Burnout

2.2. Life Satisfaction

2.3. Loneliness and Fear of Alienation

2.4. Hypotheses

- By empirically testing the mediating effects of loneliness and fear of alienation on the relationship between school burnout and life satisfaction, this study extends the theoretical horizon of mental health research among university students. Furthermore, it moves beyond simple associations to clarify the underlying mechanisms.

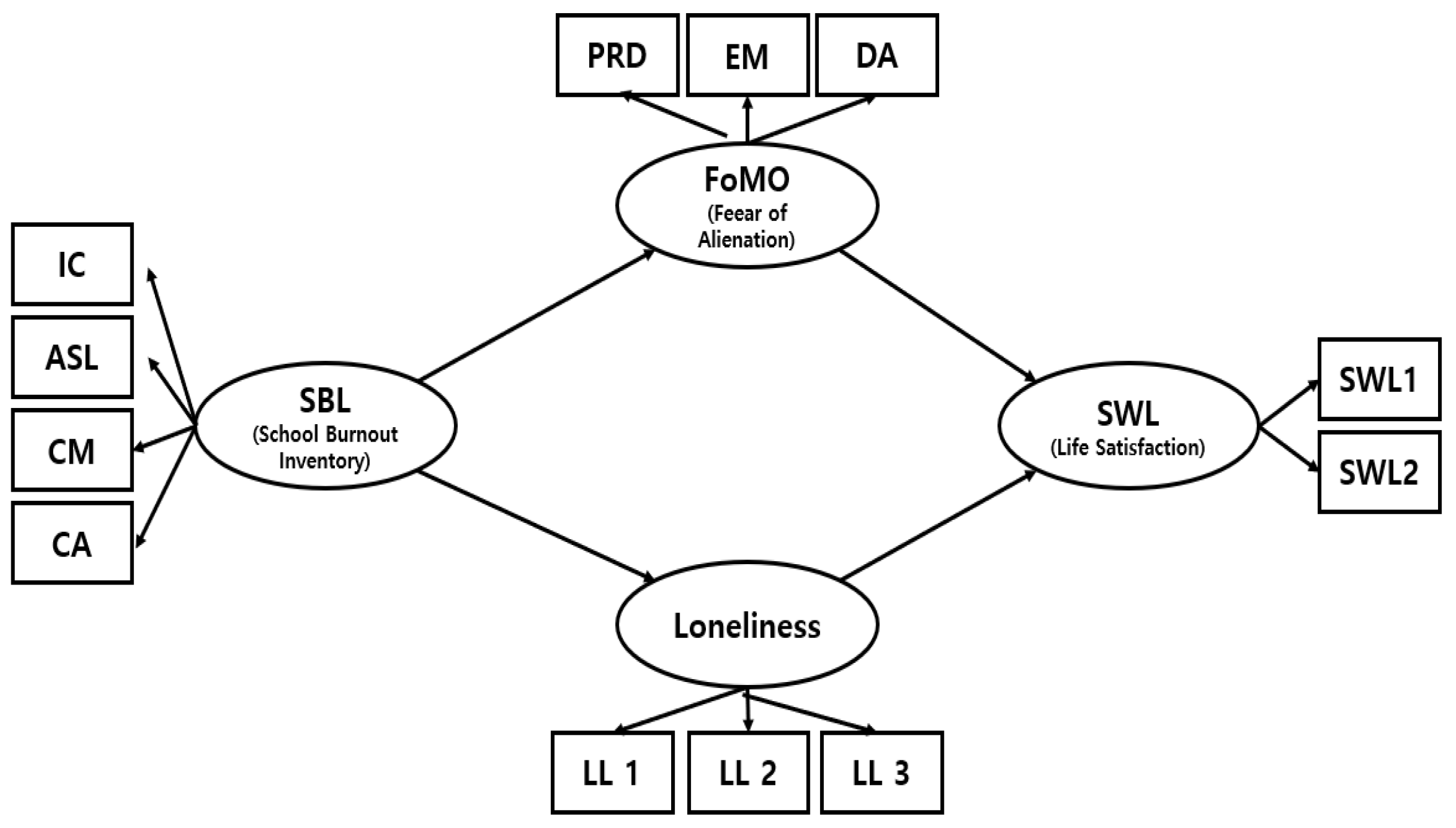

- Through a multiple mediation analysis using structural equation modeling (SEM), this study elucidates the causal links among the variables more precisely. This goes beyond conventional correlational analyses to propose a more sophisticated theoretical model of the impact of school burnout on life satisfaction through psychological mediators.

- Conducting an empirical study in domestic (Korean) university students provides context-specific findings, thus helping to concretize knowledge in a field that often relies on international research. These localized insights can inform interventions and policies tailored to the context of Korean higher education.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. School Burnout Inventory (SBL)

3.2.2. Loneliness

3.2.3. Fear of Alienation (FoMO)

3.2.4. Life Satisfaction (SWL)

3.3. Data Analysis

- Step 1: Descriptive and Reliability Analysis

- Frequency analyses were conducted to describe the demographic characteristics of the sample.

- Cronbach’s α coefficients were calculated to assess the internal consistency of each scale.

- Step 2: Correlation and Descriptive Statistics

- Pearson’s product–moment correlation analysis was performed to examine the relationships among the study variables.

- Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) were calculated for all key variables.

- Step 3: Structural Equation Modeling for Mediation

- Following Anderson and Gerbing’s (1988) two-step approach, SEM was used to examine the mediating effects of loneliness and fear of alienation on the relationship between school burnout and life satisfaction.

- The measurement models were specified before testing the structural model. For single-factor constructs (loneliness and life satisfaction), item parceling was applied based on factor analysis to form parcel indicators (Kline, 2015).

- Step 1—Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA): The reliability and validity of the measurement model were evaluated. Model fit was assessed using indices such as χ2, χ2/df, normed fit index (NFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Factor loadings, critical ratios (C.R.s), the average variance extracted (AVE), and the composite reliability (CR) were calculated to examine the construct reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity.

- Step 2—Structural model testing: The structural model was estimated using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). Model fit indices (χ2, χ2/df, NFI, TLI, CFI, RMSEA) were used to assess the overall fit. Path coefficients were tested for statistical significance at the α = 0.05 level. The Sobel test was conducted for mediation pathways to examine the significance of the total and indirect effects.

3.4. Measurement Model Assessment

- χ2 (chi-square), reflecting the degree to which the covariance matrix reproduces the observed data, and

- TLI, CFI, and RMSEA, indicating how well the specified measurement model fits relative to a null model and whether the fit meets the conventional thresholds.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.2. Model Fit and Mediating Effects

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Limitation

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J. J. (2016). College students as emerging adults: The developmental implications of the college context. Emerging Adulthood, 4(3), 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bask, M., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2013). Burned out to drop out: Exploring the relationship between school burnout and school dropout. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28(2), 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J. T., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Thisted, R. A. (2006). Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychology and Aging, 21(1), 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conlin, L., Billings, A. C., & Averset, L. (2016). Time-shifting vs. appointment viewing: The role of fear of missing out within TV consumption behaviors. Communication & Society, 29(4), 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Horwitz, J., & Emmons, R. A. (1985). Happiness of the very wealthy. Social Indicators Research, 16, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J. J., Schaufeli, W. B., & Ahola, K. (2008). The job demands-resources model: A three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment, and work engagement. Work & Stress, 22(3), 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, R. H., & Smith, G. T. (1994). Formulating clinical research hypotheses as structural equation models: A conceptual overview. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62(3), 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, C., & Kim, I. S. (2022). Structural relationships between fear of missing out, SNS-addictive tendencies, and depression in colleges. Journal of Korean Society of Integrative Medicine, 10(3), 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, K. C. (2020). Dissatisfaction with academics and employment… Increase in university dropout rates. Jeonnam Maeil. Available online: http://www.jndn.com/article.php?aid=1592215675302045005 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Joo, E. S., Jeon, S. Y., & Shim, S. J. (2018). Study on the validation of the Korean version of the Fear of Missing Out (K-FoMO) scale for Korean college students. The Journal of the Korea Contents Association, 18(2), 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M. S., & Yang, S. J. (2019). On the mediating effects of harmonious and obsessive passion and grit in the relationship between parent attachment and life satisfaction. The Korean Journal of Developmental Psychology, 32(2), 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, R., & Vallade, J. I. (2022). Exploring connections in the online learning environment: Student perceptions of rapport, climate, and loneliness. Interactive Learning Environments, 30(10), 1794–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G. S. (2010). Structural equation modeling analysis. Hannarae. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. H., Ma, Y. Y., Go, M. S., & Jung, I. K. (2013). The effects of coping strategy on academic burnout and school adjustment in Chinese adolescents. Journal of Korean Home Economics Education Association, 25(2), 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koivuneva, K., & Ruokamo, H. (2022). Assessing university students’ study-related burnout and academic well-being in digital learning environments: A systematic literature review. Seminar.net, 18(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kum, J. H. (2018). Effects of achievement goal orientation, academic self-efficacy, academic achievement and quality of life on academic stress of nursing college students. Asia-Pacific Journal of Multimedia Services Convergent with Art, Humanities, and Sociology, 8(10), 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H., Shaheen, A., Rasool, I., & Shafi, M. (2016). Psychological distress and life satisfaction among university students. Journal of Psychology & Clinical Psychiatry, 5(3), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. H., & Lee, H. H. (2021). Relationships of companionship, school life satisfaction, and psychological happiness of university students participating in club sports activities. Journal of Sport and Leisure Studies, 83, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. T., Noh, M. J., Kwon, M. O., & Yi, H. U. (2013). A study on the relations among SNS users’ loneliness, self-disclosure, social support and life satisfaction. The Journal of Internet Electronic Commerce Research, 13(2), 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M. R., & Park, B. H. (2018). Development and validation of the college student burnout scale. Korean Journal of Educational Psychology, 32(2), 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesener, T., Pleiss, L. S., Gusy, B., & Wolter, C. (2020). The study demands-resources framework: An empirical introduction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 5183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C. (2018). Burnout: A multidimensional perspective. In Professional burnout (pp. 19–32). CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, R. W., Bauer, K. N., & Fincham, F. D. (2015). School burnout: Diminished academic and cognitive performance. Learning and Individual Differences, 42, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, R. W., Sanchez-Gonzalez, M. A., Brown, P. C., Koutnik, A. P., & Fincham, F. D. (2014). School burnout and cardiovascular functioning in young adult males: A hemodynamic perspective. Stress, 17(1), 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdinezhad, V. (2015). Students’ satisfaction with life and its relation to school burnout. Bulgarian Journal of Science and Education Policy, 9(2), 254. [Google Scholar]

- Neugarten, B. L., Havighurst, R. J., & Tobin, S. S. (1961). The measurement of life satisfaction. Journal of Gerontology, 16(2), 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouweneel, E., Le Blanc, P. M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2011). Flourishing students: A longitudinal study on positive emotions, personal resources, and study engagement. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(2), 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H. G. (2018). The effect of coaching leadership on resilience, interpersonal competence and job performance. The Journal of the Korea Contents Association, 18(10), 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. H., & Kim, E. H. (2017). Relationship of academic stress, ego-resilience and health promoting behaviors in nursing students. Journal of Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society, 18(9), 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(2), 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K. J., Menon, K. R., & Thattil, A. (2018). Academic stress and its sources among university students. Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal, 11(1), 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, Í. J., Pereira, R., Freire, I. V., de Oliveira, B. G., Casotti, C. A., & Boery, E. N. (2018). Stress and quality of life among university students: A systematic literature review. Health Professions Education, 4(2), 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, R. (2017). Loneliness might be a killer, but what’s the best way to protect against it? JAMA, 318(19), 1853–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Cutrona, C. E. (1980). The revised UCLA loneliness scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(3), 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmela-Aro, K., Kiuru, N., Leskinen, E., & Nurmi, J. E. (2009). School burnout inventory (SBI): Reliability and validity. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 25(1), 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Martínez, I. M., Pinto, A. M., Salanova, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(5), 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheepers, R. A., Hilverda, F., & Vollmann, M. (2024). Study demands and resources affect academic well-being and life satisfaction of undergraduate medical students in the Netherlands. Medical Education, 58(9), 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E. J., & Kim, J. H. (2017). Development and verification on the effectiveness of teachers’ resilience group counseling program using encouraging-strokes. The Journal of Korean Teacher Education, 34(3), 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankland, R., Kotsou, I., Vallet, F., Bouteyre, E., Dantzer, C., & Leys, C. (2019). Burnout in university students: The mediating role of sense of coherence on the relationship between daily hassles and burnout. Higher Education, 78, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J. M., Lea, E. Y., & Yang, N. M. (2015). The effects of career calling on career decision-making self-efficacy and life satisfaction in college students. Journal of Social Science, 54(1), 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J. W., & Yang, N. M. (2016). The impact of maladaptive perfectionism on life satisfaction in college student: Mediating effect of ego-resilience and active coping. Korean Journal of Counseling, 17(1), 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoliker, B. E., & Lafreniere, K. D. (2015). The influence of perceived stress, loneliness, and learning burnout on university students’ educational experience. College Student Journal, 49(1), 146–160. [Google Scholar]

- Vansoeterstede, A., Cappe, E., Lichtle, J., & Boujut, E. (2023). A systematic review of longitudinal changes in school burnout among adolescents: Trajectories, predictors, and outcomes. Journal of Adolescence, 95(2), 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Sun, W., & Wu, H. (2022). Associations between academic burnout, resilience and life satisfaction among medical students: A three-wave longitudinal study. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., & Wu, H. (2022). Associations between maladaptive perfectionism and life satisfaction among Chinese undergraduate medical students: The mediating role of academic burnout and the moderating role of self-esteem. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 774622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S. J., & Kim, Y. J. (2018). The relationship between fear of missing out (FoMO), SNS proneness, depression and online compulsive buying behaviors on university students. Korean Journal of Youth Studies, 25(11), 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Latent Variable | Observed Variable | B | Β | S.E. | C.R. | AVE | Construct Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School burnout | Difficulty adjusting to classes | 1.000 | 0.576 | 1.525 | 0.803 | ||

| Apathy toward school life | 1.028 | 0.646 | 0.050 | 20.411 *** | |||

| Identity confusion | 1.175 | 0.646 | 0.052 | 22.769 *** | |||

| Career anxiety | 1.211 | 0.781 | 0.054 | 22.462 *** | |||

| Loneliness | Loneliness 1 | 1.000 | 0.875 | 1.840 | 0.963 | ||

| Loneliness 2 | 1.014 | 0.873 | 0.021 | 48.897 *** | |||

| Loneliness 3 | 1.158 | 0.896 | 0.023 | 50.783 *** | |||

| Fear of alienation | Perceived relative deprivation | 1.000 | 0.743 | 1.509 | 0.802 | ||

| Extrinsic motivation | 1.277 | 0.983 | 0.035 | 36.516 *** | |||

| Need for belonging | 0.951 | 0.714 | 0.031 | 31.156 *** | |||

| Life satisfaction | Life satisfaction 1 | 1.000 | 0.776 | 2.598 | 1.454 | ||

| Life satisfaction 2 | 1.010 | 0.869 | 0.010 | 25.067 *** |

| Variable | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | School Burnout | Loneliness | Fear of Alienation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School burnout | 2.54 | 0.71 | 0.130 | −0.162 | 1 | ||

| Loneliness | 1.97 | 0.59 | 0.684 | 0.509 | 0.519 ** | 1 | |

| Fear of alienation | 2.28 | 0.85 | 0.445 | −0.251 | 0.527 ** | 0.439 ** | 1 |

| Life satisfaction | 3.55 | 0.75 | −0.185 | −0.236 | −0.426 ** | −0.491 ** | −0.271 ** |

| Variable | χ2 | df | NFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full multiple mediation model | 492.465 | 47 | 0.958 | 0.946 | 0.962 | 0.073 |

| Partial multiple mediation model | 416.346 | 46 | 0.965 | 0.955 | 0.968 | 0.067 |

| Model fit indices | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≤0.10 |

| Types | B | β | S.E. | C.R. | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School burnout → Loneliness | 0.461 | 0.620 | 0.021 | 22.297 | *** |

| School burnout → Fear of alienation | 0.832 | 0.700 | 0.035 | 24.103 | *** |

| Loneliness → Life satisfaction | −0.486 | −0.375 | 0.043 | −11.325 | *** |

| Fear of alienation → Life satisfaction | 0.096 | 0.119 | 0.032 | 2.973 | *** |

| School burnout → Life satisfaction | −0.390 | −0.405 | 0.046 | −8.498 | *** |

| Types | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Total Effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| School burnout | Loneliness | 0.620 | 0.620 *** | |

| Fear of alienation | 0.700 | 0.700 *** | ||

| Life satisfaction | −0.405 | −0.149 | −0.554 *** | |

| Loneliness | Life satisfaction | −0.375 | −0.375 *** | |

| Fear of alienation | Life satisfaction | 0.119 | 0.119 *** | |

| Types | A | Sa | b | Sb | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School burnout → Loneliness → Life satisfaction | 0.461 | 0.021 | −0.486 | 0.043 | −10.048 *** |

| School burnout → Fear of alienation → Life satisfaction | 0.832 | 0.035 | 0.096 | 0.032 | 4.489 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shim, T.; Go, E. The Impact of School Burnout on Life Satisfaction Among University Students: The Mediating Effects of Loneliness and Fear of Alienation. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1083. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081083

Shim T, Go E. The Impact of School Burnout on Life Satisfaction Among University Students: The Mediating Effects of Loneliness and Fear of Alienation. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1083. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081083

Chicago/Turabian StyleShim, Taeeun, and Eunsun Go. 2025. "The Impact of School Burnout on Life Satisfaction Among University Students: The Mediating Effects of Loneliness and Fear of Alienation" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1083. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081083

APA StyleShim, T., & Go, E. (2025). The Impact of School Burnout on Life Satisfaction Among University Students: The Mediating Effects of Loneliness and Fear of Alienation. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1083. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081083