Mindfulness-Based Art Interventions for Students: A Meta-Analysis Review of the Effect on Anxiety

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

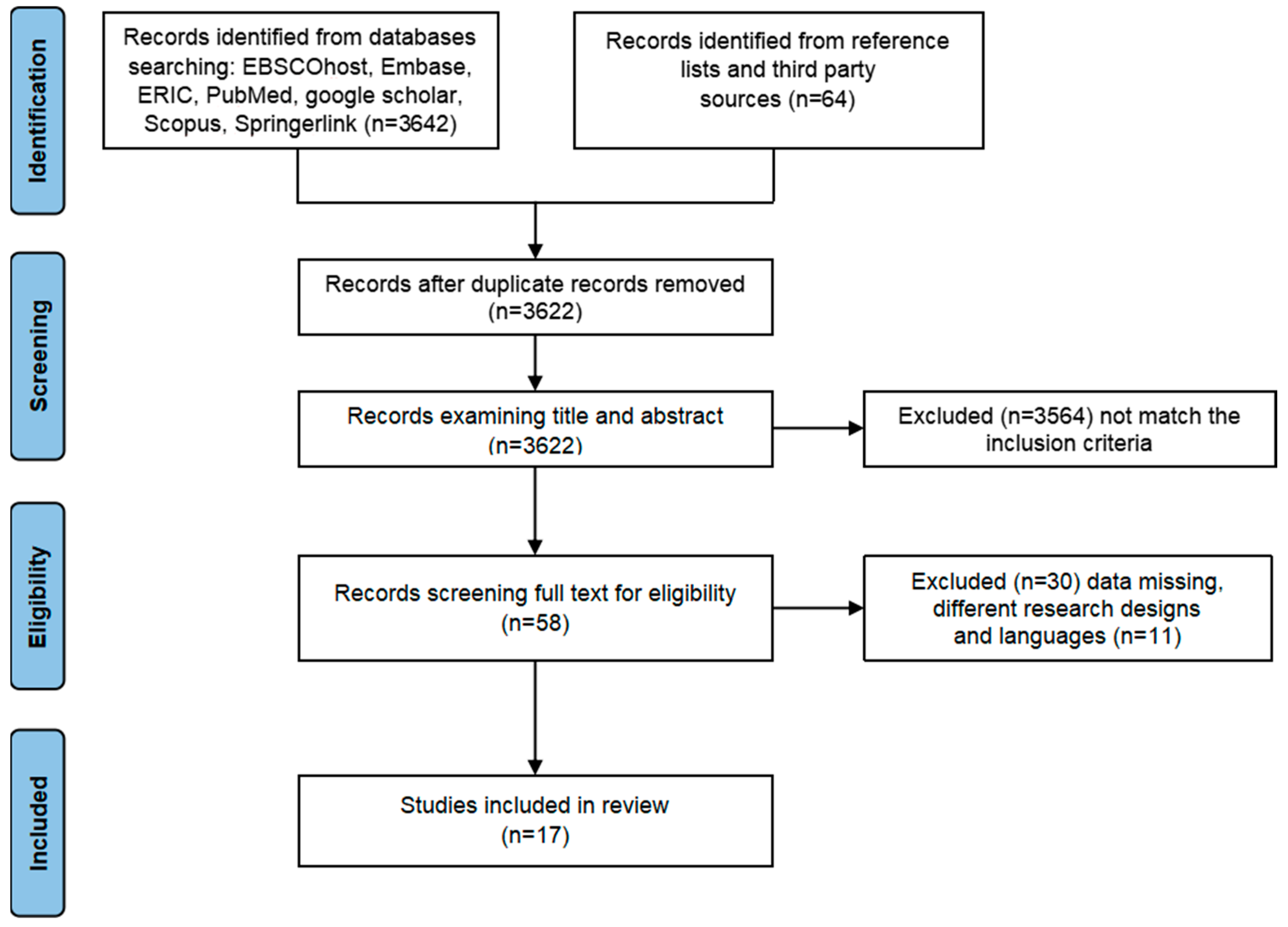

3.1. Study Selection Procedure

3.2. Study Quality Assessment

3.3. Study Characteristics

3.4. Effect Size and Homogeneity Testing

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

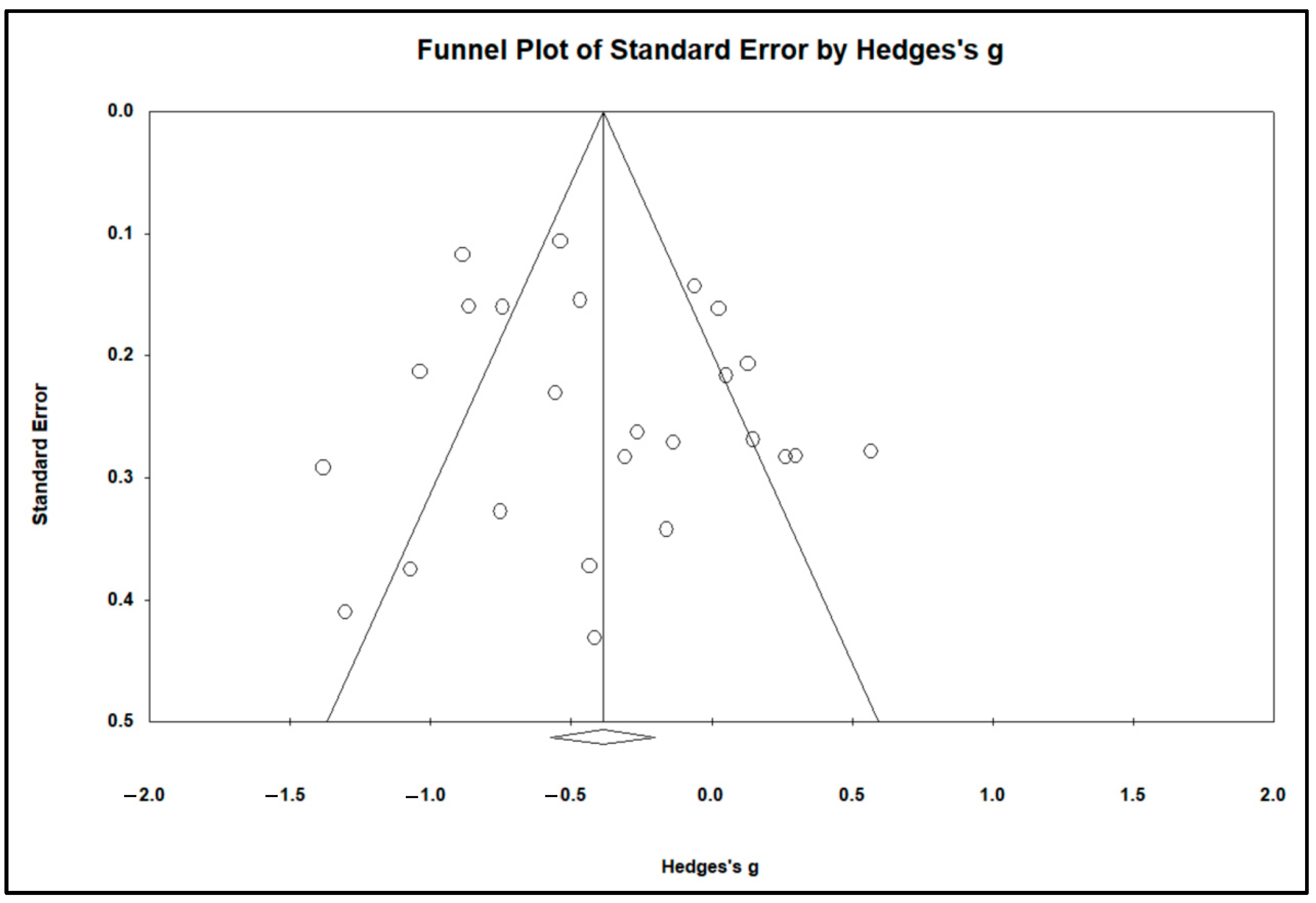

3.6. Publication Bias

3.7. Subgroup Analyses

3.7.1. Learning Stage

3.7.2. Intervention Type

3.7.3. Research Design

3.7.4. Intervention Duration

3.7.5. Measuring Instrument

3.8. Meta-Regression

4. Discussion

4.1. The Relationship Between MBAIs and Students’ Anxiety

4.2. Moderating Effects

4.2.1. Learning Stage

4.2.2. Intervention Type

4.2.3. Research Design

4.2.4. Intervention Duration

4.2.5. Measuring Instrument

4.2.6. Sample Size

5. Research Limitations and Further Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ando, M., & Ito, S. (2014). Potentiality of mindfulness art therapy short version on mood of healthy people. Health, 2014, 46134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ando, M., & Ito, S. (2016). Changes in autonomic nervous system activity and mood of healthy people after mindfulness art therapy short version. Health, 8(4), 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Baumgartner, P., Jennifer, N., Schneider, P., & Tamera, R. (2023). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction on academic resilience and performance in college students. Journal of American College Health, 71(6), 1916–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerse, M. E., Van Lith, T., & Stanwood, G. (2020). Therapeutic psychological and biological responses to mindfulness-based art therapy. Stress and Health, 36(4), 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, K., & Dorjee, D. (2016). The impact of a mindfulness-based stress reduction course (MBSR) on well-being and academic attainment of sixth-form students. Mindfulness, 7(1), 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghoff, C. R., Wheeless, L. E., Ritzert, T. R., Wooley, C. M., & Forsyth, J. P. (2017). Mindfulness meditation adherence in a college sample: Comparison of a 10-min versus 20-min 2-week daily practice. Mindfulness, 8, 1513–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokoch, R., & Hass-Cohen, N. (2021). Effectiveness of a school-based mindfulness and art therapy group program. Art Therapy, 38(3), 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumariu, L. E., Waslin, S. M., Gastelle, M., Kochendorfer, L. B., & Kerns, K. A. (2023). Anxiety, academic achievement, and academic self-concept: Meta-analytic syntheses of their relations across developmental periods. Development and Psychopathology, 35(4), 1597–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, C. R. (2025). Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Education: A Review. In Challenges of educational innovation in contemporary society (pp. 389–426). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Card, N. A. (2015). Applied meta-analysis for social science research. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Carsley, D., & Heath, N. L. (2018). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based colouring for test anxiety in adolescents. School Psychology International, 39(3), 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsley, D., & Heath, N. L. (2019). Evaluating the effectiveness of a mindfulness coloring activity for test anxiety in children. The Journal of Educational Research, 112(2), 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsley, D., Heath, N. L., & Fajnerova, S. (2015). Effectiveness of a classroom mindfulness coloring activity for test anxiety in children. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 31(3), 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsley, D., Khoury, B., & Heath, N. L. (2018). Effectiveness of mindfulness interventions for mental health in schools: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 9, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshure, A., Stanwood, G. D., Van Lith, T., & Pickett, S. M. (2023). Distinguishing difference through determining the mechanistic properties of mindfulness based art therapy. Current Research in Behavioral Sciences, 4, 100106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coholic, D. A. (2011). Exploring the feasibility and benefits of arts-based mindfulness-based practices with young people in need: Aiming to improve aspects of self-awareness and resilience. In Child & youth care forum. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Collaborators, G. M. D. (2022). Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(2), 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craske, M. G., Rauch, S. L., Ursano, R., Prenoveau, J., Pine, D. S., & Zinbarg, R. E. (2011). What is an anxiety disorder? Focus, 9(3), 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, G., & Brown, P. M. (2019). A comparison of the positive effects of structured and nonstructured art activities. Art Therapy, 36(1), 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, N. A., & Kasser, T. (2005). Can coloring mandalas reduce anxiety? Art Therapy, 22(2), 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias Lopes, L. F., Chaves, B. M., Fabrício, A., Porto, A., Machado de Almeida, D., Obregon, S. L., Pimentel Lima, M., Vieira da Silva, W., Camargo, M. E., & da Veiga, C. P. (2020). Analysis of well-being and anxiety among university students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, K., Stargell, N. A., & Mauk, G. W. (2018). Effectiveness of coloring mandala designs to reduce anxiety in graduate counseling students. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 13(3), 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulambarkar, N., Seo, B., Testerman, A., Rees, M., Bausback, K., & Bunge, E. (2023). Meta-analysis on mindfulness-based interventions for adolescents’ stress, depression, and anxiety in school settings: A cautionary tale. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 28(2), 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galla, B. (2024). How motivation restricts the scalability of universal school-based mindfulness interventions for adolescents. Child Development Perspectives, 18(3), 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmon, B., Philbrick, J., Daniel Becker, M., John Schorling, M., Padrick, M., & Goodman, M. (2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for chronic pain: A systematic review. Journal of Pain Management, 7(1), 23. [Google Scholar]

- Gotink, R. A., Meijboom, R., Vernooij, M. W., Smits, M., & Hunink, M. M. (2016). 8-week mindfulness based stress reduction induces brain changes similar to traditional long-term meditation practice—A systematic review. Brain and Cognition, 108, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouda, S., Luong, M. T., Schmidt, S., & Bauer, J. (2016). Students and teachers benefit from mindfulness-based stress reduction in a school-embedded pilot study. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, L. F., Dariotis, J. K., Mendelson, T., & Greenberg, M. T. (2012). A school-based mindfulness intervention for urban youth: Exploring moderators of intervention effects. Journal of Community Psychology, 40(8), 968–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecucci, A., Pappaianni, E., Siugzdaite, R., Theuninck, A., & Job, R. (2015). Mindful emotion regulation: Exploring the neurocognitive mechanisms behind mindfulness. BioMed Research International, 2015(1), 670724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (2014). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J. P., & Thompson, S. G. (2002). Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 21(11), 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, L., Hempel, S., Ewing, B. A., Apaydin, E., Xenakis, L., Newberry, S., Colaiaco, B., Maher, A. R., Shanman, R. M., & Sorbero, M. E. (2017). Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 51(2), 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, N. J., Furbert, L., & Sweetingham, E. (2019). Cognitive and affective benefits of coloring: Two randomized controlled crossover studies. Art Therapy, 36(4), 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013a). Full catastrophe living, revised edition: How to cope with stress, pain and illness using mindfulness meditation. Hachette UK. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013b). Some reflections on the origins of MBSR, skillful means, and the trouble with maps. In Mindfulness (pp. 281–306). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kmet, L. M., Cook, L. S., & Lee, R. C. (2004). Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, D. M., & Vinod Kumar, S. (2024). Mindfulness-based intervention on psychological factors among students: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 42(2), 279–304. [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma, D., & Kumano, H. (2009). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and cancer: A meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer, 18(6), 571–579. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.-L. (2018). Why color mandalas? A study of anxiety-reducing mechanisms. Art Therapy, 35(1), 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lensen, J., Stoltz, S., Kleinjan, M., Speckens, A., Kraiss, J., & Scholte, R. (2021). Mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention for elementary school teachers: A mixed method study. Trials, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léger-Goodes, T., Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C., Herba, C. M., Taylor, G., Mageau, G. A., Chadi, N., & Lefrançois, D. (2023). Videoconference-led art-based interventions for children during COVID-19: Comparing mindful mandala and emotion-based drawings. Mental Health Science, 1(3), 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, R. J., & Pillemer, D. B. (1984). Summing up: The science of reviewing research. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C., Léger-Goodes, T., Mageau, G. A., Taylor, G., Herba, C. M., Chadi, N., & Lefrançois, D. (2021). Online art therapy in elementary schools during COVID-19: Results from a randomized cluster pilot and feasibility study and impact on mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantzios, M., & Giannou, K. (2018). When did coloring books become mindful? Exploring the effectiveness of a novel method of mindfulness-guided instructions for coloring books to increase mindfulness and decrease anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor, S. M., Saleem, T., Azmat, J., & Arouj, K. (2017). Mandala-coloring as a therapeutic intervention for anxiety reduction in university students. Pakistan Armed Forces Medical Journal, 67(6), 904–907. [Google Scholar]

- Öhman, A. (2008). Fear and anxiety. In Handbook of emotions (pp. 709–729). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pearcey, S., Gordon, K., Chakrabarti, B., Dodd, H., Halldorsson, B., & Creswell, C. (2021). Research Review: The relationship between social anxiety and social cognition in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 62(7), 805–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapgay, L., & Bystrisky, A. (2009). Classical mindfulness: An introduction to its theory and practice for clinical application. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1172(1), 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S. M., & Morrison, G. R. (2013). Experimental research methods. In Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (pp. 1007–1029). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, G., & Topham, P. (2012). The impact of social anxiety on student learning and well-being in higher education. Journal of Mental Health, 21(4), 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santomauro, D. F., Herrera, A. M. M., Shadid, J., Zheng, P., Ashbaugh, C., Pigott, D. M., Abbafati, C., Adolph, C., Amlag, J. O., & Aravkin, A. Y. (2021). Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 398(10312), 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari Ozturk, C., & Kilicarslan Toruner, E. (2022). The effect of mindfulness-based mandala activity on anxiety and spiritual well-being levels of senior nursing students: A randomized controlled study. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 58(4), 2897–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanche, E., Vøllestad, J., Binder, P.-E., Hjeltnes, A., Dundas, I., & Nielsen, G. H. (2020). Participant experiences of change in mindfulness-based stress reduction for anxiety disorders. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 15(1), 1776094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuman-Olivier, Z., Trombka, M., Lovas, D. A., Brewer, J. A., Vago, D. R., Gawande, R., Dunne, J. P., Lazar, S. W., Loucks, E. B., & Fulwiler, C. (2020). Mindfulness and behavior change. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 28(6), 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C. D. (1983). State-trait anxiety inventory for adults. APA PsycNet. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strohmaier, S., Jones, F. W., & Cane, J. E. (2021). Effects of length of mindfulness practice on mindfulness, depression, anxiety, and stress: A randomized controlled experiment. Mindfulness, 12, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalheimer, W., & Cook, S. (2002). How to calculate effect sizes from published research: A simplified methodology. Work-Learning Research, 1(9), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge, J. M. (2000). The age of anxiety? The birth cohort change in anxiety and neuroticism, 1952–1993. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vago, D. R., & Silbersweig, D. A. (2012). Self-awareness, self-regulation, and self-transcendence (S-ART): A framework for understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Vennet, R., & Serice, S. (2012). Can coloring mandalas reduce anxiety? A replication study. Art Therapy, 29(2), 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viechtbauer, W. (2007). Confidence intervals for the amount of heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 26(1), 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. M. G. (2008). Mindfulness, depression and modes of mind. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., Fang, Y., Chen, H., Zhang, T., Yin, X., Man, J., Yang, L., & Lu, M. (2021). Global, regional and national burden of anxiety disorders from 1990 to 2019: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 30, e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yılmazer, E., Hamamci, Z., & Türk, F. (2024). Effects of mindfulness on test anxiety: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1401467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y., Bao, X., Yan, J., Miao, H., & Guo, C. (2021). Anxiety and depression in Chinese students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 697642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | School students with anxiety in different educational environments | Population with anxiety outside of school |

| Intervention | Mindfulness based art interventions (MBAIs) | Mindfulness interventions only or art interventions only |

| Comparison | Other interventions reducing students’ anxiety | Mindfulness based art interventions (MBAIs) |

| Outcome | The effects of MBAIs on students’ anxiety | The effects of MBAIs on students’ other mental problems |

| Study design | One-group pre–post-test, quasi-experiment, and randomized controlled trial (RCT) designs | Correlational study, surveys, and reviews study |

| Study data | Studies must report sufficient data to calculate effect size (such as mean, standard deviation, sample size, t-value, p-value) | Studies that did not report key statistics and whose information could not be completed after contacting the corresponding author |

| Publication language | Published in English | Publications in other languages |

| References | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X | XI | XII | XIII | XIV | Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Carsley et al., 2015) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Strong |

| (Carsley & Heath, 2019) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Strong |

| (Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al., 2021) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Strong |

| (Léger-Goodes et al., 2023) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Strong |

| (Carsley & Heath, 2018) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Strong |

| (Beerse et al., 2020) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Strong |

| (Ando & Ito, 2014) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Moderate |

| (Curry & Kasser, 2005) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Strong |

| (Van Der Vennet & Serice, 2012) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Strong |

| (Duong et al., 2018) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Strong |

| (Mantzios & Giannou, 2018) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | Strong |

| (Cross & Brown, 2019) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Strong |

| (Holt et al., 2019) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Strong |

| (Sari Ozturk & Kilicarslan Toruner, 2022) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Strong |

| (Lee, 2018) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Strong |

| (Noor et al., 2017) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | Moderate |

| (Ando & Ito, 2016) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Moderate |

| No. | References | Participants | Intervention Types | Duration (Weeks) | Sample Size | Study Designs | Measuring Instrument |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (Carsley et al., 2015) | Primary school students | Mandala coloring | 1 | 52 | RCT | STAI |

| 2 | (Carsley & Heath, 2019) | Primary school students | Mandala coloring | 1 | 152 | RCT | STAI |

| 3 | (Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al., 2021) | Primary school students | Mandala coloring | 5 | 22 | Quasi-experiment | Others |

| 4 | (Léger-Goodes et al., 2023) | Primary school students | Mandala coloring | 10 | 165 | Quasi-experiment | Others |

| 5 | (Carsley & Heath, 2018) | Middle school students | Mandala coloring | 1 | 193 | RCT | STAI |

| 6 | (Beerse et al., 2020) | University students | MBAI (mindfulness practice and intentional art making with earth-based clay) | 5 | 77 | RCT | Others |

| 7 | (Ando & Ito, 2014) | University students | MBAI (Mindfulness therapy included breathing, yoga, and body scan; Arts items using clay, collage, or drawing) | 4 | 39 | Quasi-experiment | Others |

| 8 | (Curry & Kasser, 2005) | University students | Mandala coloring | 1 | 57 | RCT | STAI |

| 9 | (Van Der Vennet & Serice, 2012) | University students | Mandala coloring | 1 | 50 | RCT | STAI |

| 10 | (Duong et al., 2018) | University students | Mandala coloring | 5 | 93 | Quasi-experiment | STAI |

| 11 | (Mantzios & Giannou, 2018) | University students | Mandala coloring | 1 | 84 | RCT | STAI |

| 12 | (Cross & Brown, 2019) | University students | Mandala coloring | 1 | 76 | Quasi-experiment | STAI |

| 13 | (Holt et al., 2019) | University students | Mandala coloring | 1 | 99 | RCT | STAI |

| 14 | (Sari Ozturk & Kilicarslan Toruner, 2022) | University students | Mandala coloring | 3 | 170 | RCT | STAI |

| 15 | (Lee, 2018) | University students | Mandala coloring | 1 | 99 | RCT | STAI |

| 16 | (Noor et al., 2017) | University students | Mandala coloring | 1 | 100 | One-group PR-PO | STAI |

| 17 | (Ando & Ito, 2016) | University students | MBAI (Mindfulness therapy included breathing, yoga, and body scan; Arts items using clay, collage, or drawing) | 1 | 20 | One-group PR-PO | Others |

| Effect Size and 95% CI | Heterogeneity Test | Tau-Squared | Test of Null (Two-Tailed) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | g | 95% CI | Q | p | I2 | Tau2 | SE | Tau | Z | p |

| 25 | −0.387 | [−0.573, −0.201] | 113.994 | 0.000 | 78.946 | 0.161 | 0.070 | 0.401 | −4.081 | 0.000 |

| Moderator Variables | k | Hedges’ g | SE | 95% CI | I2 | QW | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning stage | QB = 1.914 (p = 0.167) | ||||||

| K-12 | 5 | −0.128 | 0.213 | [−0.545, 0.288] | 81.958 | 22.170 | 0.546 |

| Higher education | 20 | −0.445 | 0.103 | [−0.657, −0.254] | 75.972 | 79.074 | 0.000 |

| Intervention type | QB = 6.602 (p = 0.010) | ||||||

| Mandala coloring | 21 | −0.312 | 0.103 | [−0.513, −0.111] | 80.986 | 105.187 | 0.002 |

| MBAI | 4 | −0.803 | 0.161 | [−1.119, −0.487] | 4.994 | 3.158 | 0.000 |

| Research design | QB = 7.977 (p = 0.005) | ||||||

| One-group experiment | 4 | −0.816 | 0.153 | [−1.117, −0.516] | 61.490 | 7.790 | 0.000 |

| Control-group experiment | 21 | −0.293 | 0.104 | [−0.497, −0.089] | 76.585 | 85.417 | 0.005 |

| Intervention duration | QB = 1.254 (p = 0.263) | ||||||

| ≤1 week | 18 | −0.330 | 0.122 | [−0.570, −0.090] | 81.805 | 93.435 | 0.007 |

| >1 week | 7 | −0.533 | 0.134 | [−0.797, −0.270] | 64.434 | 16.870 | 0.000 |

| Measuring instrument | QB = 9.154 (p = 0.002) | ||||||

| State-trait anxiety inventory | 19 | −0.282 | 0.110 | [−0.497, −0.066] | 82.104 | 100.582 | 0.000 |

| Other instruments | 6 | −0.748 | 0.108 | [−0.960, −0.536] | 0.000 | 3.845 | 0.572 |

| Variable | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | Z | p | QM | df |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple size | −0.000 | 0.002 | [−0.004, 0.003] | −0.120 | 0.903 | 0.010 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, Z.; Xiao, L.; Ahmad, N.A.; Roslan, S.; Burhanuddin, N.A.N.; Gao, J.; Huang, C. Mindfulness-Based Art Interventions for Students: A Meta-Analysis Review of the Effect on Anxiety. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081078

Zhu Z, Xiao L, Ahmad NA, Roslan S, Burhanuddin NAN, Gao J, Huang C. Mindfulness-Based Art Interventions for Students: A Meta-Analysis Review of the Effect on Anxiety. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081078

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Zhihui, Lin Xiao, Nor Aniza Ahmad, Samsilah Roslan, Nur Aimi Nasuha Burhanuddin, Jianping Gao, and Cuihua Huang. 2025. "Mindfulness-Based Art Interventions for Students: A Meta-Analysis Review of the Effect on Anxiety" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081078

APA StyleZhu, Z., Xiao, L., Ahmad, N. A., Roslan, S., Burhanuddin, N. A. N., Gao, J., & Huang, C. (2025). Mindfulness-Based Art Interventions for Students: A Meta-Analysis Review of the Effect on Anxiety. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081078