Jurymen Seldom Rule Against a Person That They Like: The Relationship Between Emotions Towards a Defendant, the Understanding of Case Facts, and Juror Judgments in Civil Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Psychological Research on the Relationship Between Emotions and Decisions

1.2. The Role of Cognitive Consistency in Decision-Making

1.3. Emotion and Legal Decision-Making

1.4. Does Judicial Rehabilitation Diminish the Relationship Between Emotion and Case Judgments?

1.5. Study Overview and Hypotheses

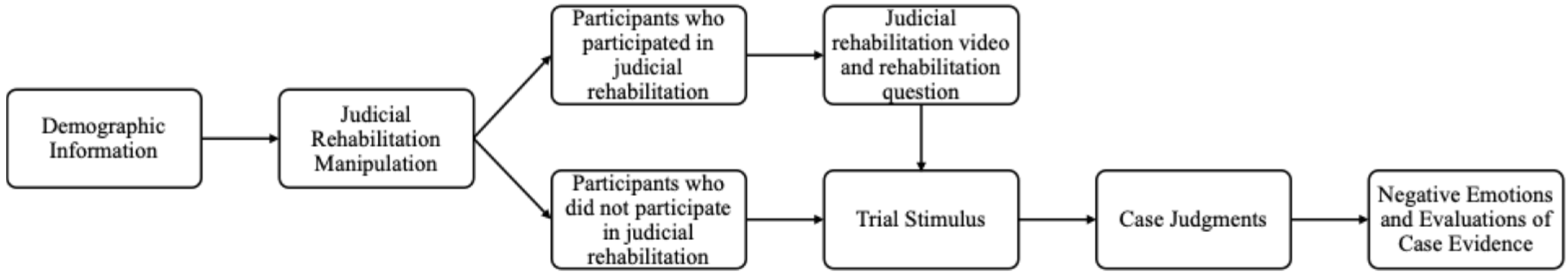

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Materials and Measures

2.2.1. Judicial Rehabilitation Manipulation

2.2.2. Trial Stimulus

2.2.3. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Assumption Checks

2.3.2. Preliminary Analysis Plan

2.3.3. Direct Effects (Hypothesis 1)

2.3.4. Indirect Effects (Hypotheses 2 and 3)

2.3.5. Supplemental Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Direct Effect Hypotheses (Hypothesis 1)

3.2.1. Verdicts (Hypothesis 1a)

3.2.2. Damage Awards (Hypothesis 1b)

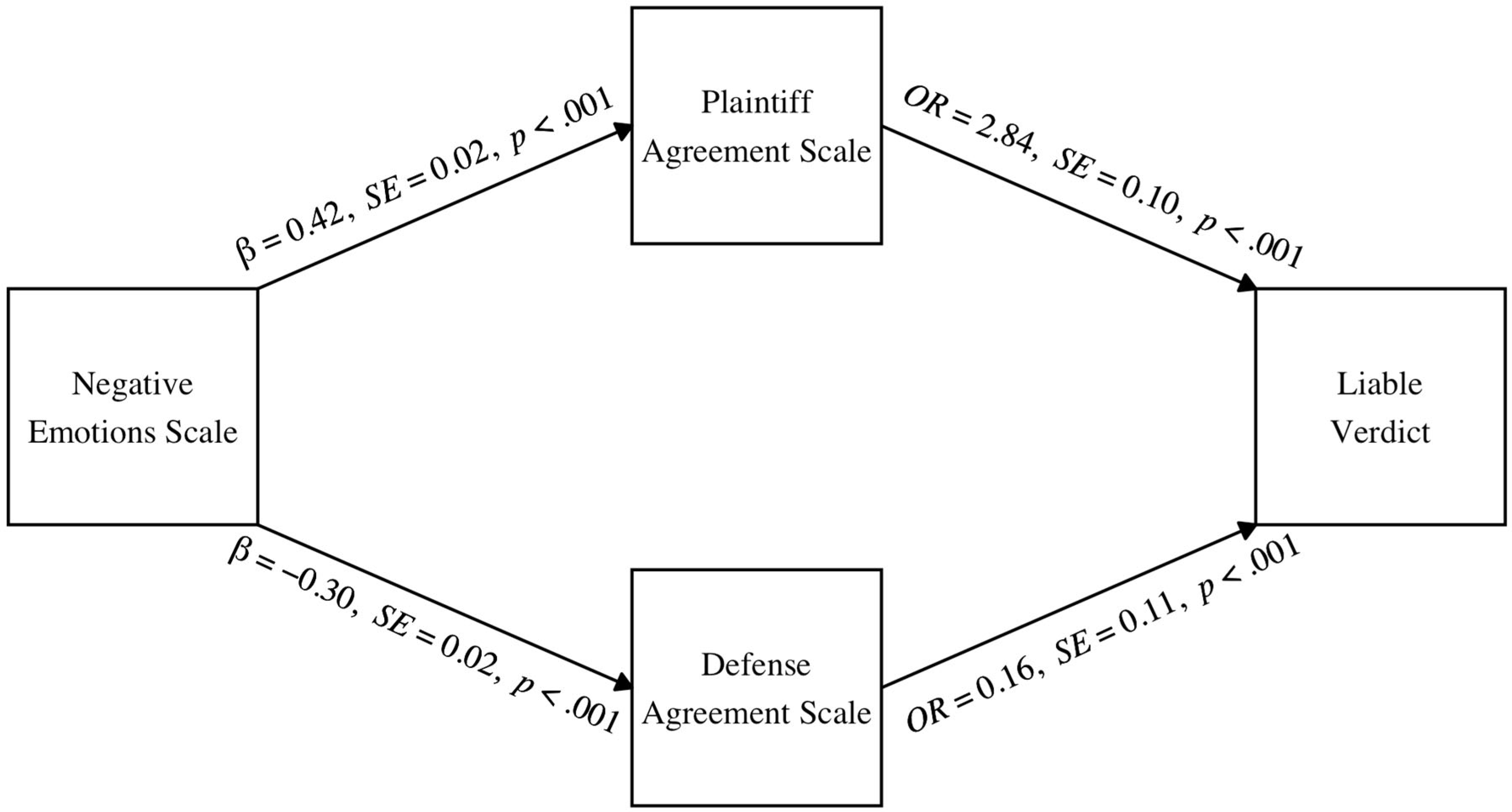

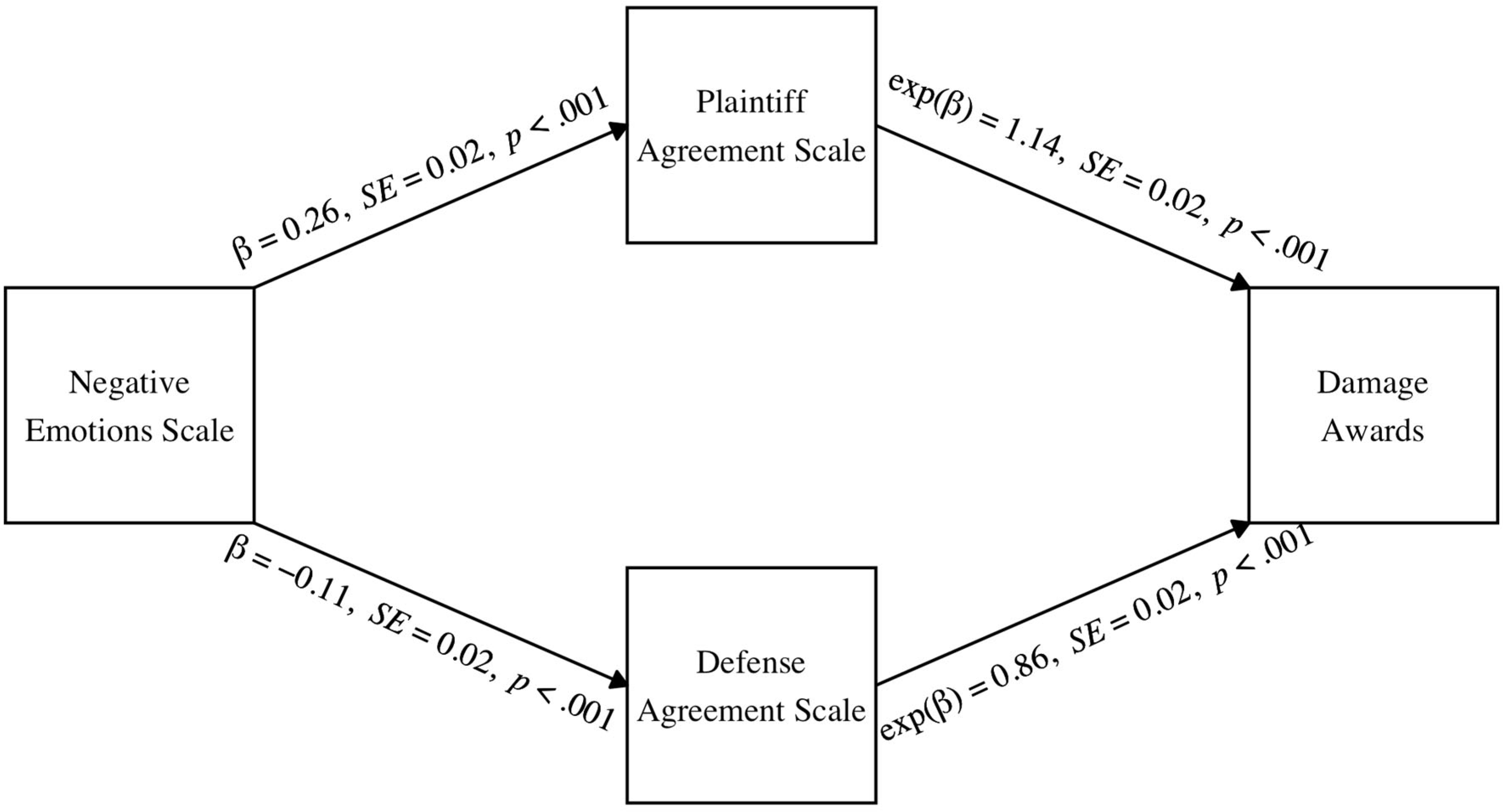

3.3. Indirect Effect Hypotheses (Hypotheses 2 and 3)

3.3.1. Verdicts

3.3.2. Damage Awards

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Contributions

4.2. Legal Implications

4.3. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alicke, M. D. (2000). Culpable control and the psychology of blame. Psychological Bulletin, 126(4), 556–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ask, K., & Pina, A. (2011). On being angry and punitive: How anger alters perception of criminal intent. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2(5), 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Associated Press. (2022). Jury foreman: Ahmaud Arbery killers showed ‘so much hatred’. ABC News. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20220320161857/https://abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory/jury-foreman-ahmaud-arbery-killers-showed-hatred-83181168 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Axt, J. R., Nguyen, H., & Nosek, B. A. (2018). The judgment bias task: A flexible method for assessing individual differences in social judgment biases. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandes, S. (1999). When victims seek closure: Forgiveness, vengeance and the role of government. Fordham Urban Law Journal, 27, 1599–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenhausen, G. V., Sheppard, L. A., & Kramer, G. P. (1994). Negative affect and social judgment: The differential impact of anger and sadness. European Journal of Social Psychology, 24(1), 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, B. H., Golding, J. M., Neuschatz, J., Kimbrough, C., Reed, K., Magyarics, C., & Luecht, K. (2017). Mock juror sampling issues in jury simulation research: A meta-analysis. Law and Human Behavior, 41(1), 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buhrmester, M. D., Talaifar, S., & Gosling, S. D. (2018). An evaluation of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, its rapid rise, and its effective use. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(2), 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, M. (2022). Exclusive: Juror speaks out after convicting Elizabeth Holmes. ABC News. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20250715184223/https://abcnews.go.com/US/exclusive-juror-speaks-convicting-elizabeth-holmes/story?id=82082789 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Coppock, A. (2019). Generalizing from survey experiments conducted on mechanical turk: A replication approach. Political Science Research and Methods, 7(3), 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, C. B., & Kovera, M. B. (2010). The effects of rehabilitative voir dire on juror bias and decision making. Law and Human Behavior, 34(3), 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahò, M. (2025). Emotional responses in clinical ethics consultation decision-making: An exploratory study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 748–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ error and the future of human life. Scientific American, 271(4), 144–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devine, P. G., Forscher, P. S., Austin, A. J., & Cox, W. T. (2012). Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(6), 1267–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feigenson, N., & Park, J. (2006). Emotions and attributions of legal responsibility and blame: A research review. Law and Human Behavior, 30(2), 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feigenson, N., Park, J., & Salovey, P. (2001). The role of emotions in comparative negligence judgments. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(3), 576–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, R. A., & Mendes, W. B. (2018). Emotion, health decision making, and health behaviour. Psychology & Health, 33(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishfader, V. L., Howells, G. N., Katz, R. C., & Teresi, P. S. (1996). Evidential and extralegal factors in juror decisions: Presentation mode, retention, and level of emotionality. Law and Human Behavior, 20(5), 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgas, J. P. (1995). Mood and judgment: The affect infusion model (AIM). Psychological Bulletin, 117(1), 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangemi, A., Rizzotto, C., Riggio, F., Dahò, M., & Mancini, F. (2025). Guilt emotion and decision-making under uncertainty. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1518752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawronski, B., Hofmann, W., & Wilbur, C. J. (2006). Are “implicit” attitudes unconscious? Consciousness and Cognition, 15(3), 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gewehr, E., Volbert, R., Merschhemke, M., Santtila, P., & Pülschen, S. (2025). Cognitions and emotions about child sexual abuse (CECSA): Development of a self-report measure to predict bias in child sexual abuse investigations. Psychology, Crime & Law, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glöckner, A., & Witteman, C. (2010). Beyond dual-process models: A categorisation of processes underlying intuitive judgement and decision making. Thinking & Reasoning, 16(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, J. H., Lerner, J. S., & Tetlock, P. E. (1999). Rage and reason: The psychology of the intuitive prosecutor. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29(5–6), 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J. K., Cryder, C. E., & Cheema, A. (2013). Data collection in a flat world: The strengths and weaknesses of Mechanical Turk samples. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 26(3), 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, E., Johns, M., & Smith, A. (2001). The effects of defendant conduct on jury damage awards. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(2), 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, J. (2005). Emotion and cognition in moral judgment: Evidence from neuroimaging. In J. P. Changeux, A. R. Damasio, W. Singer, & Y. Christen (Eds.), Neurobiology of human values. Research and perspectives in neurosciences (pp. 57–66). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J., & Haidt, J. (2002). How (and where) does moral judgment work? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 6(12), 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, J. D. (2023). The dual-process theory of moral judgment does not deny that people can make compromise judgments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(6), e2220396120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haidt, J. (2003). The moral emotions. In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of affective sciences (Vol. 11, pp. 852–870). Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannaford-Agor, P. L., & Waters, N. L. (2004). Examining voir dire in California. Judicial Council of California, Administrative Office of the Courts. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield, E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Rapson, R. L. (1993). Emotional contagion. Current directions in Psychological Science, 2, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis second edition: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heider, F. (1946). Attitudes and cognitive organization. The Journal of Psychology, 21(1), 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irvine, K., Hoffman, D. A., & Wilkinson-Ryan, T. (2018). Law and psychology grows up, goes online, and replicates. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 15(2), 320–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahan, D. M. (2013). Ideology, motivated reasoning, and cognitive reflection: An experimental study. Judgment and Decision Making, 8, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., & Frederick, S. (2002). Representativeness revisited: Attribute substitution in intuitive judgment. In T. Gilovich, D. Griffin, & D. Kahneman (Eds.), Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment (pp. 49–81). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, G. P., Kerr, N. L., & Carroll, J. S. (1990). Pretrial publicity, judicial remedies, and jury bias. Law and Human Behavior, 14(5), 409–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, C. K., Skinner, A. L., Cooley, E., Murrar, S., Brauer, M., Devos, T., Calanchini, J., Xiao, Y. J., Pedram, C., Marshburn, C. K., Simon, S., Blanchar, J. C., Joy-Gaba, J. A., Conway, J., Redford, L., Klein, R. A., Roussos, G., Schellhaas, F. M. H., Burns, M., … Nosek, B. A. (2016). Reducing implicit racial preferences: II. Intervention effectiveness across time. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145(8), 1001–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenth, R. (2024). emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means, R package version 1.10.0; Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Lerner, J. S., Dorison, C. A., & Klusowski, J. (2023). How do emotions affect decision making? In A. Scarantino (Ed.), Emotion theory: The Routledge comprehensive guide (pp. 447–468). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J. S., & Keltner, D. (2000). Beyond valence: Toward a model of emotion-specific influences on judgement and choice. Cognition & Emotion, 14(4), 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J. S., Li, Y., Valdesolo, P., & Kassam, K. S. (2015). Emotion and decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 799–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, D. S. (2022). Neuroscience of emotion, cognition, and decision making: A review. Medical Research Archives, 10(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, J. D., & Arndt, J. (2000). Understanding the limits of limiting instructions: Social psychological explanations for the failures of instructions to disregard pretrial publicity and other inadmissible evidence. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 6(3), 677–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, C. G., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. (1979). Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(11), 2098–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millard, S. P. (2013). EnvStats: An R package for environmental statistics. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez, N., Schweitzer, K., Chai, C. A., & Myers, B. (2015). Negative emotions felt during trial: The effect of fear, anger, and sadness on juror decision making. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 29(2), 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, M. E., & Grosjean, S. (2004). Confirmation bias. In R. F. Pohl (Ed.), Cognitive illusions: A handbook on fallacies and biases in thinking, judgement and memory (pp. 79–96). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluck, E. L., Porat, R., Clark, C. S., & Green, D. P. (2021). Prejudice reduction: Progress and challenges. Annual Review of Psychology, 72(1), 533–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peter-Hagene, L. C., Bean, S., & Salerno, J. M. (2023). Emotion and legal judgment. In D. DeMatteo, & K. C. Scherr (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of psychology and law (pp. 726–741). Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter-Hagene, L. C., & Bottoms, B. L. (2017). Attitudes, anger, and nullification instructions influence jurors’ verdicts in euthanasia cases. Psychology, Crime & Law, 23(10), 983–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter-Hagene, L. C., & Ratliff, C. L. (2021). When jurors’ moral judgments result in jury nullification: Moral outrage at the law as a mediator of euthanasia attitudes on verdicts. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 28(1), 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phalen, H. J., Salerno, J. M., & Nadler, J. (2021). Emotional evidence in court. In S. A. Bandes, J. L. Madeira, K. D. Temple, & E. K. White (Eds.), Research handbook on law and emotion (pp. 288–311). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, Z. H., Choo, S., Leshin, J. C., Lindquist, K. A., & Nam, C. S. (2022). Emotion depends on context, culture and their interaction: Evidence from effective connectivity. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 17(2), 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. (2023). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Revelle, W. (2023). psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. Northwestern University. (R package version 2.3.3). Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Reyna, V. F. (1992). Reasoning, remembering, and their relationship: Social, cognitive, and developmental issues. In M. L. Howe, C. J. Brainerd, & V. F. Reyna (Eds.), Development of long-term retention (pp. 103–132). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, S. E., Reyna, V. F., & Mills, B. (2008). Risk taking under the influence: A fuzzy-trace theory of emotion in adolescence. Developmental Review, 28(1), 107–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohrer, J. M., Hünermund, P., Arslan, R. C., & Elson, M. (2022). That’s a lot to process! Pitfalls of popular path models. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 5(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. J. (1960). A structural theory of attitude dynamics. Public Opinion Quarterly, 24(2), 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, U., Roesch, S., Greitemeyer, T., & Weiner, B. (2004). A meta-analytic review of help giving and aggression from an attributional perspective: Contributions to a general theory of motivation. Cognition and Emotion, 18(6), 815–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, J. E., Carlson, K. A., Meloy, M. G., & Yong, K. (2008). The goal of consistency as a cause of information distortion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 137(3), 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salerno, J. M. (2017). Seeing red: Disgust reactions to gruesome photographs in color (but not in black and white) increase convictions. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 23(3), 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, J. M. (2021). The impact of experienced and expressed emotion on legal factfinding. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 17, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, J. M., Campbell, J. C., Phalen, H. J., Bean, S. R., Hans, V. P., Spivack, D., & Ross, L. (2021). The impact of minimal versus extended voir dire and judicial rehabilitation on mock jurors’ decisions in civil cases. Law and Human Behavior, 45(4), 336–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, J. M., & Phalen, H. J. (2019). The impact of gruesome photographs on mock jurors’ emotional responses and decision making in a civil case. DePaul Law Review, 69, 633–656. Available online: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol69/iss2/14 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Schuller, R. A., Erentzen, C., Vo, A., & Li, D. (2015). Challenge for cause: Bias screening procedures and their application in a canadian courtroom. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 21(4), 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N. (2012). Feelings-as-information theory. In P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 289–308). Sage. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N., & Clore, G. L. (1983). Mood, misattribution, and judgments of well-being: Informative and directive functions of affective states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(3), 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shultz, T. R., & Lepper, M. R. (1996). Cognitive dissonance reduction as constraint satisfaction. Psychological Review, 103(2), 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, D., Ahn, M., Stenstrom, D. M., & Read, S. J. (2020). The adversarial mindset. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 26(3), 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D., & Read, S. J. (2025). Toward a general framework of biased reasoning: Coherence-based reasoning. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 20(3), 421–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, D., Stenstrom, D. M., & Read, S. J. (2015). The coherence effect: Blending cold and hot cognitions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(3), 369–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spellman, B. A. (1996). Acting as intuitive scientists: Contingency judgments are made while controlling for alternative potential causes. Psychological Science, 7(6), 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunstein, C. (2002). The law of group polarization. Journal of Political Philosophy, 10(2), 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas ex rel. Thomas v. Mercy Hospitals East Communities. (2017). No. SC96034 (Mo. 2017). Available online: https://law.justia.com/cases/missouri/supreme-court/2017/sc96034.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- U.S. Eleventh Circuit District Judicial Council. (2024). Eleventh circuit pattern jury instructions, civil cases. U.S. Eleventh Circuit District Judicial Council. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Ninth Circuit Committee on Model Criminal Jury Instructions. (2022). Manual of model civil jury instructions. U.S. Ninth Circuit Committee on Model Criminal Jury Instructions. [Google Scholar]

- van Kleef, G. A., & Côté, S. (2022). The social effects of emotions. Annual Review of Psychology, 73(1), 629–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y. (2021). What is the role of emotions in educational leaders’ decision making? Proposing an organizing framework. Educational Administration Quarterly, 57(3), 372–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wason, P. C. (1960). On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 12(3), 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wason, P. C., & Evans, J. S. B. (1974). Dual processes in reasoning? Cognition, 3(2), 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H., Averick, M., Bryan, J., Chang, W., McGowan, L. D., François, R., Grolemund, G., Hayes, A., Henry, L., Hester, J., Kuhn, M., Pedersen, T. L., Miller, E., Bache, S. M., Müller, K., Ooms, J., Robinson, D., Seidel, D. P., Spinu, V., … Yutani, H. (2019). Welcome to the tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software, 4(43), 1686–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wistrich, A. J., Rachlinski, J. J., & Guthrie, C. (2015). Heart versus head: Do judges follow the law of follow their feelings. Texas Law Review, 93, 855–923. Available online: https://texaslawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Rachlinski-93-4.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

| Demographic | n or Mean | % or Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 39.87 | 12.61 | |

| Gender | |||

| Men | 775 | 37.97 | |

| Women | 1266 | 62.03 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 1580 | 77.41 | |

| Black/African American | 181 | 8.87 | |

| Native American | 6 | 0.29 | |

| Asian | 123 | 6.03 | |

| Hispanic | 119 | 5.83 | |

| Other | 32 | 1.57 | |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 9 | 0.44 | |

| High school degree or equivalent | 178 | 8.72 | |

| Some college but no degree | 479 | 23.47 | |

| Technical or Vocational school | 62 | 3.04 | |

| Associate degree | 251 | 12.30 | |

| Bachelor degree | 769 | 37.68 | |

| Graduate degree | 260 | 12.74 | |

| Doctorate degree | 33 | 1.62 | |

| Parental Status | |||

| Parent | 1083 | 53.06 | |

| Not a Parent | 958 | 46.94 | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 826 | 40.47 | |

| Never Married | 802 | 39.29 | |

| Divorced | 212 | 10.39 | |

| Widowed | 72 | 3.53 | |

| Partnered | 87 | 4.26 | |

| Separated | 42 | 2.06 | |

| Income | 59,377.63 | 43,181.41 | |

| Measure | All Cases N = 2041 | Medical Malpractice Misdiagnosis (Study 1, n = 713) | Insurance Bad Faith (Study 2, n = 677) | Wrongful Birth (Study 3, n = 651) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Emotions Scale | 2.27 (1.21) | 1.98 (1.17) | 2.26 (1.11) | 2.60 (1.26) |

| Plaintiff Agreement Scale | 4.08 (1.05) | 3.75 (1.00) | 4.70 (0.92) | 3.80 (0.93) |

| Defense Agreement Scale | 3.74 (1.03) | 4.40 (0.80) | 3.30 (1.12) | 3.47 (0.75) |

| Liable Verdict | 1246 (61%) | 268 (38%) | 481 (71%) | 497 (76%) |

| Damage Award (Median) | 5,000,000.00 (500,000.00, 30,000,000.00) | 15,000,000.00 (5,000,000.00, 25,000,000.00) | 450,000.00 (300,000.00, 500,000.00) | 30,000,000.00 (10,500,000.00, 37,000,000.00) |

| Damage Award (Mean) | 13,896,213.75 (15,824,630.69) | 16,514,074.54 (11,787,776.63) | 427,818.30 (164,166.72) | 25,540,445.07 (15,408,670.16) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Phalen, H.J.; Bettis, T.C.; Bean, S.R.; Salerno, J.M. Jurymen Seldom Rule Against a Person That They Like: The Relationship Between Emotions Towards a Defendant, the Understanding of Case Facts, and Juror Judgments in Civil Trials. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070965

Phalen HJ, Bettis TC, Bean SR, Salerno JM. Jurymen Seldom Rule Against a Person That They Like: The Relationship Between Emotions Towards a Defendant, the Understanding of Case Facts, and Juror Judgments in Civil Trials. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):965. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070965

Chicago/Turabian StylePhalen, Hannah J., Taylor C. Bettis, Samantha R. Bean, and Jessica M. Salerno. 2025. "Jurymen Seldom Rule Against a Person That They Like: The Relationship Between Emotions Towards a Defendant, the Understanding of Case Facts, and Juror Judgments in Civil Trials" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070965

APA StylePhalen, H. J., Bettis, T. C., Bean, S. R., & Salerno, J. M. (2025). Jurymen Seldom Rule Against a Person That They Like: The Relationship Between Emotions Towards a Defendant, the Understanding of Case Facts, and Juror Judgments in Civil Trials. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070965