Can Self-Esteem Protect the Subjective Well-Being of Women in Their 20s from the Effects of Social Media Use? The Moderating Role of Self-Esteem

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Media Use and Subjective Well-Being

1.2. Self-Esteem as a Moderator

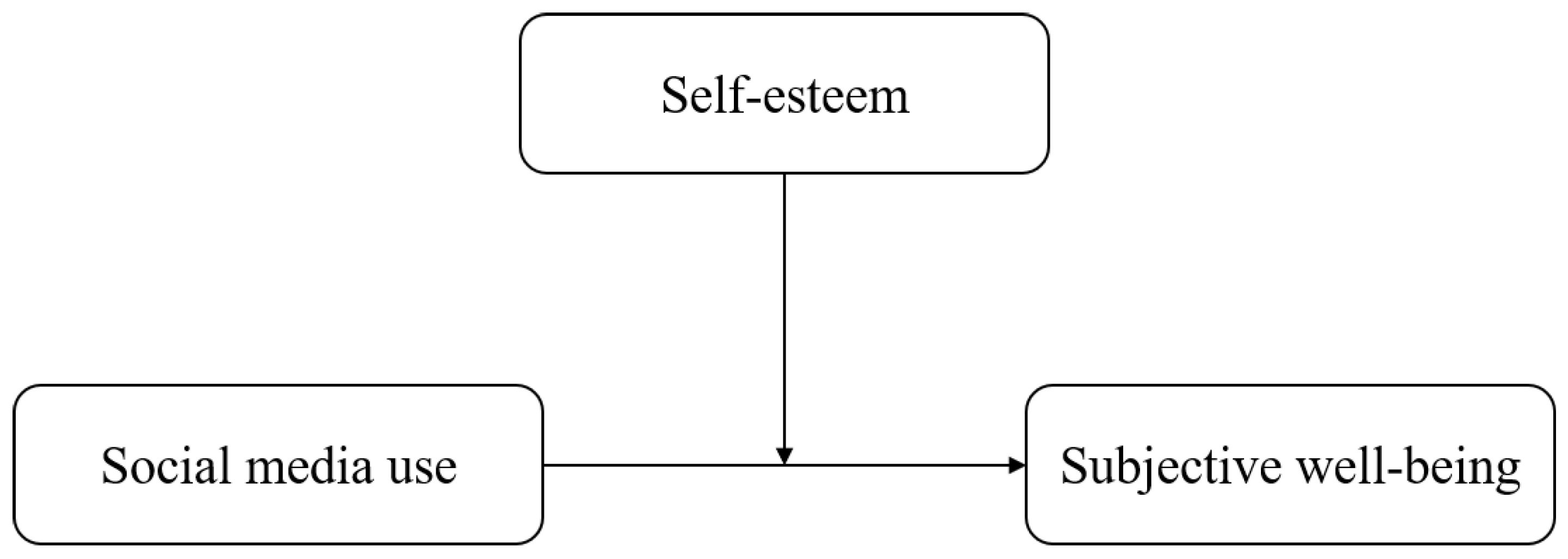

1.3. Aims of Study and Research Questions

- RQ1: Does SMU increase or decrease the SWB of South Korean women in their 20s?

- RQ1-1: Is SMU positively associated with SWB of South Korean women in their 20s?

- RQ1-2: Is SMU negatively associated with SWB of South Korean women in their 20s?

- RQ2: Does the impact of SMU on SWB vary based on the level of self-esteem among South Korean women in their 20s?

- RQ2-1: Among individuals with high levels of self-esteem, is higher SMU associated with higher SWB (rich-get-richer hypothesis)?

- RQ2-2: Among individuals with low levels of self-esteem, is higher SMU associated with lower SWB (poor-get-poorer hypothesis)?

2. Methods

2.1. Data Overview

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Respondents

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Variable Correlations

3.3. Association Between Social Media Use and Subjective Well-Being and Moderating Effects of Self-Esteem

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2016). Introduction to the psychology of self-esteem. In F. Holloway (Ed.), Self-esteem: Perspectives, influences, and improvement strategies (pp. 1–23). Nova Science. [Google Scholar]

- Akkas, C., & Turan, A. H. (2024). Social network use and life satisfaction: A systematic review. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 28(3), 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C. S. (2015). Online social network site addiction: A comprehensive review. Current Addiction Reports, 2(2), 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S., Iqbal, N., Asif, R., Hashim, M., Farooqi, S. R., & Alimoradi, Z. (2024). Social media use and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 27(10), 704–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apaolaza, V., Hartmann, P., Medina, E., Barrutia, J. M., & Echebarria, C. (2013). The relationship between socializing on the Spanish online networking site Tuenti and teenagers’ subjective well-being: The roles of self-esteem and loneliness. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1282–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhari, A., Toms, Z., Pavlopoulou, G., Esposito, G., & Dimitriou, D. (2022). Social media use in female adolescents: Associations with anxiety, loneliness, and sleep disturbances. Acta Psychologica, 229, 103706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boursier, V., & Gioia, F. (2022). Which are the effects of body-objectification and Instagram-related practices on male body esteem? A cross-sectional study. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 19(1), 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J. D., Dutton, K. A., & Cook, K. E. (2001). From the top down: Self-esteem and self-evaluation. Cognition and Emotion, 15(5), 615–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S. F., Iftikhar, I., & Bajwa, A. M. (2023). The mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between social media use and life satisfaction: A study of WhatsApp users. Global Digital and Print Media Review, 6(I), 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., Fan, C.-Y., Liu, Q.-X., Zhou, Z.-K., & Xie, X.-C. (2016). Passive social network site use and subjective well-being: A moderated mediation model. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C., Wang, H. Y., Sigerson, L., & Chau, C. L. (2019). Do the socially rich get richer? A nuanced perspective on social network site use and online social capital accrual. Psychological Bulletin, 145(7), 734–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J. (2019). The relationship between Instagram usage (active vs. passive) and depression among female college students: The moderating role of self-esteem. The Korean Journal of Advertising and Public Relations, 21(4), 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, G., Iorio, G. D., Esposito, D., Romano, S., Panvino, F., Maggi, S., Altomonte, B., Casini, M. P., Ferrara, M., & Terrinoni, A. (2024). Scrolling through adolescence: A systematic review of the impact of TikTok on adolescent mental health. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Oishi, S. (2002). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and life satisfaction. In C. R. Snyder, & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (2nd ed., pp. 63–73). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E., Pressman, S. D., Hunter, J., & Delgadillo-Chase, D. (2017). If, why, and when subjective well-being influences health, and future needed research. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 9(2), 133–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D.-W., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook ‘friends’: Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1143–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R. A., & Diener, E. (1985). Personality correlates of subjective well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 11(1), 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eraslan-Capan, B. (2015). Interpersonal sensitivity and problematic Facebook use in Turkish university students. The Anthropologist, 21, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabio, R. A., & Tripodi, R. (2024). Exploring social media appearance preoccupation in relation to self-esteem, well-being, and mental health. Health Psychology Report, 12(4), 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forest, A. L., & Wood, J. V. (2012). When social networking is not working: Individuals with low self-esteem recognize but do not reap the benefits of self-disclosure on Facebook. Psychological Science, 23(3), 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2020). Toward an integrated and differential approach to the relationships between loneliness, different types of Facebook use, and adolescents’ depressed mood. Communication Research, 47(5), 701–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerson, J., Plagnol, A. C., & Corr, P. J. (2016). Subjective well-being and social media use: Do personality traits moderate the impact of social comparison on Facebook? Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godard, R., & Holtzman, S. (2024). Are active and passive social media use related to mental health, well-being, and social support outcomes? A meta-analysis of 141 studies. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 29(1), zmad055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haferkamp, N., Eimler, S. C., Papadakis, A.-M., & Kruck, J. V. (2012). Men are from Mars, women are from Venus? Examining gender differences in self-presentation on social networking sites. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15(2), 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Heine, S. J., & Lehman, D. R. (2004). Move the body, change the self: Acculturative effects on the self-concept. In M. Schaller, & C. S. Crandall (Eds.), The psychological foundations of culture (pp. 305–331). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C. (2021). Correlations of online social network size with well-being and distress: A meta-analysis. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 15(2), Article 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A. M., & Buckingham, J. T. (2005). Self-esteem as a moderator of the effect of social comparison on women’s body image. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24(8), 1164–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, V., Rudnev, M., Aryanto, C. B., Balgiu, B. A., Caudek, C., Datu, J. A. D., Guse, T., Kyriazos, T., Lambert, L., Mishra, K. K., Puente-Díaz, R., Rice, S. P. M., Singh, K., Sumi, K., Tong, K. K., Yaaqeib, S., Yıldırım, M., Kocjan, G. Z., & Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M. (2024). A cross-cultural evaluation of Diener’s tripartite model of subjective well-being across 16 countries. Journal of Happiness Studies, 25, Article 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsay, K., Matthes, J., Schmuck, D., & Ecklebe, S. (2023). Messaging, posting, and browsing: A mobile experience sampling study investigating youth’s social media use, affective well-being, and loneliness. Social Science Computer Review, 41(4), 1493–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F., Ding, K., & Zhao, J. (2015). The relationships among gratitude, self-esteem, social support, and life satisfaction among undergraduate students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(2), 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Information Society Development Institute. (2022). Overview of raw data. Available online: https://stat.kisdi.re.kr/kor/contents/ContentsList.html?subject=MICRO10&sub_div=D (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Korea Press Foundation. (2024). Social media users in Korea 2024. Available online: https://www.kpf.or.kr/front/research/consumerListPage.do (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Krasnova, H., Widjaja, T., Buxmann, P., Wenninger, H., & Benbasat, I. (2015). Why following friends can hurt you: An exploratory investigation of the effects of envy on social networking sites among college-age users. Information Systems Research, 26(3), 585–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraut, R., Kiesler, S., Boneva, B., Cummings, J., Helgeson, V., & Crawford, A. (2002). Internet paradox revisited. Journal of Social Issues, 58(1), 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kross, E., Verduyn, P., Demiralp, E., Park, J., Lee, D. S., Lin, N., Shablack, H., Jonides, J., & Ybarra, O. (2013). Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS ONE, 8(8), e69841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leary, M. R., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). The nature and function of self-esteem: Sociometer theory. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 32, pp. 1–62). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G., Lee, J., & Kwon, S. (2011). Use of social-networking sites and subjective well-being: A study in South Korea. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(3), 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D., & Baumeister, R. F. (2016). Social networking online and personality of self-worth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 64, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, S. M., Kluwe, K., & Bryant, F. B. (2012). Facebook use and the tendency to ruminate among college students: Testing mediational hypotheses. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 46(4), 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthar, S. S., Crossman, E. J., & Small, P. J. (2015). Resilience and adversity. In R. M. Lerner, & M. E. Lamb (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (7th ed., pp. 247–286). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C. M. S. (2022). Relationships between social networking sites use and self-esteem: The moderating role of gender. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, M., Hosman, C. M., Schaalma, H. P., & De Vries, N. K. (2004). Self-esteem in a broad-spectrum approach for mental health promotion. Health Education Research, 19(4), 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, S., Kong, F., Dong, W., Zhang, Y., Yu, T., & Jin, X. (2023). Mobile social media use and life satisfaction among adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1117745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshkovitz, K., & Hayat, T. (2021). The rich get richer: Extroverts’ social capital on Twitter. Technology in Society, 65, 101551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murari, K., Shukla, S., & Dulal, L. (2024). Social media use and social well-being: A systematic review and future research agenda. Online Information Review, 48(5), 959–982, Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najam, A. (2023). The impact of social media on mental health: A sociological analysis. Physical Education, Health and Social Sciences, 1(4), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ofcom. (2024, November 28). Online nation 2024 report. Available online: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/siteassets/resources/documents/research-and-data/online-research/online-nation/2024/online-nation-2024-report.pdf?v=386238 (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Oh, H.-J., Ozkaya, E., & LaRose, R. (2014). How does online social networking enhance life satisfaction? The relationships among online supportive interaction, affect, perceived social support, sense of community, and life satisfaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 30, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, U., Robins, R. W., & Widaman, K. F. (2012). Life-span development of self-esteem and its effects on important life outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(6), 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pew Research Center. (2024, January 31). Americans’ social media use. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2024/01/31/americans-social-media-use/ (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Pittman, M., & Reich, B. (2016). Social media and loneliness: Why an Instagram picture may be worth more than a thousand Twitter words. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinecke, L., & Trepte, S. (2014). Authenticity and well-being on social network sites: A two-wave longitudinal study on the effects of online authenticity and the positivity bias in SNS communication. Computers in Human Behavior, 30, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sagioglou, C., & Greitemeyer, T. (2014). Facebook’s emotional consequences: Why Facebook causes a decrease in mood and why people still use it. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiphoo, A. N., Halevi, L. D., & Vahedi, Z. (2020). Social networking site use and self-esteem: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Individual Differences, 153, 109639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyaninrum, I. R., Rumondor, P., Kurniawati, H., & Aziz, A. M. (2023). Promoting mental health in the digital age: Exploring the effects of social media use on psychological well-being. West Science Interdisciplinary Studies, 1(6), 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selfhout, M. H., Branje, S. J., Delsing, M., ter Bogt, T. F., & Meeus, W. H. (2009). Different types of Internet use, depression, and social anxiety: The role of perceived friendship quality. Journal of Adolescence, 32(4), 819–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setia, M. S. (2023). Cross-sectional studies. In A. L. Nichols, & J. Edlund (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of research methods and statistics for the social and behavioral sciences (Vol. 1, pp. 269–291). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D., Leonis, T., & Anandavalli, S. (2021). Belonging and loneliness in cyberspace: Impacts of social media on adolescents’ well-being. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(1), 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snodgrass, J. G., Bagwell, A., Patry, J. M., Dengah, H. F., Smarr-Foster, C., Van Oostenburg, M., & Lacy, M. G. (2018). The partial truths of compensatory and poor-get-poorer internet use theories: More highly involved video game players experience greater psychosocial benefits. Computers in Human Behavior, 78, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I., & Lee, H. J. (2022). Predictors of subjective well-being in Korean men and women: Analysis of nationwide panel survey data. PLoS ONE, 17(2), e0263170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statista. (2023, December 18). Social media use during COVID-19 worldwide—Statistics & facts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/7863/social-media-use-during-coronavirus-covid-19-worldwide/#topicOverview (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Statista. (2025a, May 22). Social media usage in South Korea—Statistics & facts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/5274/social-media-usage-in-south-korea/ (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Statista. (2025b, June 24). Social media user penetration rate in South Korea as of July 2023, by age group. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/763718/south-korea-social-media-penetration-by-age-group/ (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Statista. (2025c, June 24). Social network user penetration rate in South Korea from 2013 to 2023, by gender. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/771534/south-korea-social-media-penetration-by-gender/ (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Statista. (2025d, June 24). Most frequently used social media in South Korea as of August 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/763748/south-korea-most-popular-social-media/ (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Statista. (2025e, June 26). Distribution of Instagram users in South Korea as of April 2025, by age group and gender. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/988716/south-korea-instagram-users-by-age-group-gender/ (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Steinfield, C., Ellison, N. B., & Lampe, C. (2008). Social capital, self-esteem, and use of online social network sites: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 29(6), 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, E. M., & Koo, J. (2011). A concise measure of subjective well-being (COMOSWB): Scale development and validation. Korean Journal of Social and Personality Psychology, 25(1), 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, W. A. W., Malek, M. D. H., Yunus, A. R., Ishak, N. H., Safir, D. M., & Fahrudin, A. (2024). The impact of social media on mental health: A comprehensive review. South Eastern European Journal of Public Health, 25, 1468–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, Z., Yankouskaya, A., & Panourgia, C. (2023). Social media use, loneliness and psychological distress in emerging adults. Behaviour and Information Technology, 43(7), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromholt, M. (2016). The Facebook experiment: Quitting Facebook leads to higher levels of well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(11), 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trzesniewski, K. H., Donnellan, M. B., & Robins, R. W. (2003). Stability of self-esteem across the life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(1), 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaid, S. S., Kroencke, L., Roshanaei, M., Talaifar, S., Hancock, J. T., Back, M. D., Gosling, S. D., Ram, N., & Harari, G. M. (2024). Variation in social media sensitivity across people and contexts. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 6571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valkenburg, P. M., Koutamanis, M., & Vossen, H. G. (2017). The concurrent and longitudinal relationships between adolescents’ use of social network sites and their social self-esteem. Computers in Human Behavior, 76, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verduyn, P., Ybarra, O., Résibois, M., Jonides, J., & Kross, E. (2017). Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Social Issues and Policy Review, 11(1), 274–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Jackson, L. A., Gaskin, J., & Wang, H. X. (2014). The effects of social networking site (SNS) use on college students’ friendship and well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 37, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P., Wang, X., Wu, Y., Xie, X., Wang, X., Zhao, F., Ouyang, M., & Lei, L. (2018). Social networking sites addiction and adolescent depression: A moderated mediation model of rumination and self-esteem. Personality and Individual Differences, 127, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-S. (2013). I share therefore I am: Personality traits, life satisfaction, and Facebook check-ins. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(12), 870–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenninger, H., Krasnova, H., & Buxmann, P. (2014). Activity matters: Investigating the influence of Facebook on life satisfaction of teenage users. In M. Avital, J. M. Leimeister, & U. Schultze (Eds.), Proceedings of the 22nd European conference on information systems (pp. 1–18). ECIS. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz, D., Tucker, A., Briggs, C., & Schoemann, A. M. (2021). How and why social media affect subjective well-being: Multi-site use and social comparison as predictors of change across time. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22, 1673–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. C. (2016). Instagram use, loneliness, and social comparison orientation: Interact and browse on social media, but don’t compare. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(12), 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S., & Zhang, M. (2022). Research on the influence mechanisms of the affective and cognitive self-esteem. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L., Li, C., Zhou, T., Li, Q., & Gu, C. (2022). Social networking site use and loneliness: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychology, 156(7), 492–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | N | Percent or M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 24.60 (2.838) | |

| Education | ||

| Middle school graduation | 1 | 0.164 |

| High school graduation | 43 | 7.038 |

| University graduation | 559 | 91.489 |

| Graduate school or higher | 8 | 1.309 |

| Income (KRW) | ||

| No income | 275 | 45.008 |

| Less than 500,000 | 20 | 3.273 |

| 500,000 to under 1,000,000 | 24 | 3.928 |

| 1,000,000 to under 2,000,000 | 98 | 16.039 |

| 2,000,000 to under 3,000,000 | 167 | 27.332 |

| 3,000,000 to under 4,000,000 | 23 | 3.764 |

| 4,000,000 or more | 4 | 0.655 |

| Employment status (ref. unemployed) | ||

| Employed | 299 | 48.936 |

| Unemployed | 312 | 51.064 |

| Marital status (ref. currently unmarried) | ||

| Currently unmarried (single, widowed, or divorced) | 599 | 98.036 |

| Currently married | 12 | 1.964 |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SMU | 71.016 | 83.000 | 1 | ||

| 2. SWB | 69.325 | 13.651 | −0.140 * | 1 | |

| 3. Self-esteem | 3.065 | 0.400 | −0.031 | 0.578 * | 1 |

| Variables | B | SE | t | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | ||||

| Age | −0.029 | 0.215 | −0.135 | −0.451 | 0.393 |

| Education | 0.723 | 1.574 | 0.460 | −2.369 | 3.815 |

| Income | 0.286 | 0.663 | 0.431 | −1.016 | 1.588 |

| Employment status (ref. unemployed) | −0.296 | 2.485 | −0.522 | −6.176 | 3.583 |

| Marital status (ref. currently unmarried) | 1.322 | 3.271 | −0.404 | −7.745 | 5.101 |

| SMU | −0.112 | 0.039 | −2.862 * | −0.189 | −0.035 |

| Self-esteem | 17.126 | 1.528 | 11.208 * | 14.125 | 20.127 |

| Interaction | 0.030 | 0.013 | 2.373 * | 0.005 | 0.055 |

| R2 | 0.355 * | ||||

| Incremental R2 | 0.006 * | ||||

| F (df1, df2) | 41.452 (8, 602) | ||||

| Value of Self-Esteem | Effect | SE | t | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | ||||

| 2.665 (Low; Mean −1SD) | −0.033 | 0.008 | −4.290 * | −0.048 | −0.018 |

| 3.065 (Medium; Mean) | −0.021 | 0.006 | −3.765 * | −0.031 | −0.010 |

| 3.465 (High; Mean +1SD) | −0.009 | 0.007 | −1.193 | −0.023 | 0.006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, Y.; Lee, M. Can Self-Esteem Protect the Subjective Well-Being of Women in Their 20s from the Effects of Social Media Use? The Moderating Role of Self-Esteem. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 964. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070964

Kim Y, Lee M. Can Self-Esteem Protect the Subjective Well-Being of Women in Their 20s from the Effects of Social Media Use? The Moderating Role of Self-Esteem. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):964. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070964

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Yesolran, and Mina Lee. 2025. "Can Self-Esteem Protect the Subjective Well-Being of Women in Their 20s from the Effects of Social Media Use? The Moderating Role of Self-Esteem" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 964. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070964

APA StyleKim, Y., & Lee, M. (2025). Can Self-Esteem Protect the Subjective Well-Being of Women in Their 20s from the Effects of Social Media Use? The Moderating Role of Self-Esteem. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 964. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070964