1. Introduction

Suicide, understood as death caused by self-directed harmful behaviour with the intention to die (

Crosby et al., 2011), has become one of the major public health problems at national and international level. Already in 2014, the WHO raised the alarm on this issue and urged institutions to take specific measures and not to underestimate the risk (

World Health Organization, 2014). According to the most updated figures from the National Institute of Statistics, in 2023 in Spain there were 4116 completed suicides, 5.6% more than in 2021, 1.6% more than in 2020, and 7.4% more than in 2019 (

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2024).

Considering the entire suicide continuum, which also includes suicidal ideation and attempts of varying degrees of intensity and planning (

Posner et al., 2011), the presence of suicidal ideation is a proven risk for suicide (

De Leo et al., 2013;

Hubers et al., 2018;

Klonsky et al., 2016;

Large et al., 2020). Across the board, the prevalence of suicidal ideation is higher than that of attempts (

Castillejos et al., 2021) and 10 times higher than that of completed suicides (

Nock et al., 2008).

In relation to the above-mentioned rising figures, and with the intention of focusing on suicide prevention, attempts have been made to identify the elements that are associated with suicidal behaviour. Although suicide is a complex phenomenon influenced by multiple factors—including demographic and sociosituational variables (

Kim et al., 2016;

Lorant et al., 2018;

Nock et al., 2008;

Sadock et al., 2015;

Shah, 2011;

Westefeld et al., 2015)—this study focuses specifically on the psychopathological dimensions (

Nock et al., 2009;

Nock et al., 2010) associated with suicidal ideation, as they are often the most proximal indicators of risk in clinical outpatient settings. Hopelessness (

Franklin et al., 2017), despair (

Glenn et al., 2022), psychological pain (

Klonsky & May, 2015), impulsivity (

Moore et al., 2022), and suicidality (

Joiner, 2005;

O’Connor & Kirtley, 2018) are some of the factors that clinicians should be aware of, as they are mechanisms related to the development and increased risk of suicidal behaviour.

Once it is known which factors are related to suicidal behaviour, it seems undeniable to ask the questions: is it sufficient to know these factors to address the current suicide crisis, and why are deaths still not preventable?

Klonsky et al. (

2016) argued that the failure to predict completed suicide is due to a lack of knowledge about the processes underlying ideation and action, so theoretical explanatory models and related research should focus along these lines. Methodological approaches such as network analysis could overcome the tautological conceptualizations and reification of the common latent disorder model applied to psychology (

Borsboom & Cramer, 2013). Psychopathological symptoms are conceived as networks of symptoms that evolve over time and are causally interrelated (

Borsboom, 2017;

Borsboom & Cramer, 2013;

Fonseca-Pedrero, 2018;

Fried et al., 2016), which is why this analytical approach has been applied to suicidal behavior in recent years (

D. P. De Beurs et al., 2017;

D. De Beurs et al., 2019;

Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2020b,

2022;

Rath et al., 2019).

Most epidemiological studies have focused either on the general population or on specific psychiatric populations (psychotic patients, BPD or adolescents) (

Ducasse et al., 2020;

Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2020a;

Taylor et al., 2010;

Yates et al., 2019). In fact, the Clinical Practice Guideline on the prevention and treatment of suicidal behaviour in Spain (2012) refers only to healthcare settings (primary care, mental health centers, and hospital emergency departments) for detection and intervention within the National Health System, without including the outpatient context outside the public health system. However, this context, a priori of a less urgent and/or serious nature than the hospital, may be the ideal setting for the detection of suicidal ideation at the beginning of its development, prior to its intensification or entry into the hospital circuit after attempts.

Thus, the main objective of this study is to explore the configuration and interrelationships of psychopathological symptoms in patients attending an outpatient clinical setting, according to the presence or absence of suicidal ideation. As a second objective, another aim is to analyze whether the relationships between dimensions are different in comparison with those for the group without suicidal ideation. For this purpose, we used a methodology based on psychopathological network analysis (

Borsboom, 2017;

Epskamp et al., 2018) and a predictive model that considers these dimensions.

It was hypothesized that symptom intensity would be higher in the group with suicidal ideation, with depressive and anxious symptomatology being the most central factors in the network. Furthermore, it was expected that there would be significant differences between the networks of both groups: depression would be more central in the network of people with ideation and there would be a positive relationship between depressive and anxious symptoms and suicidal ideation.

4. Discussion

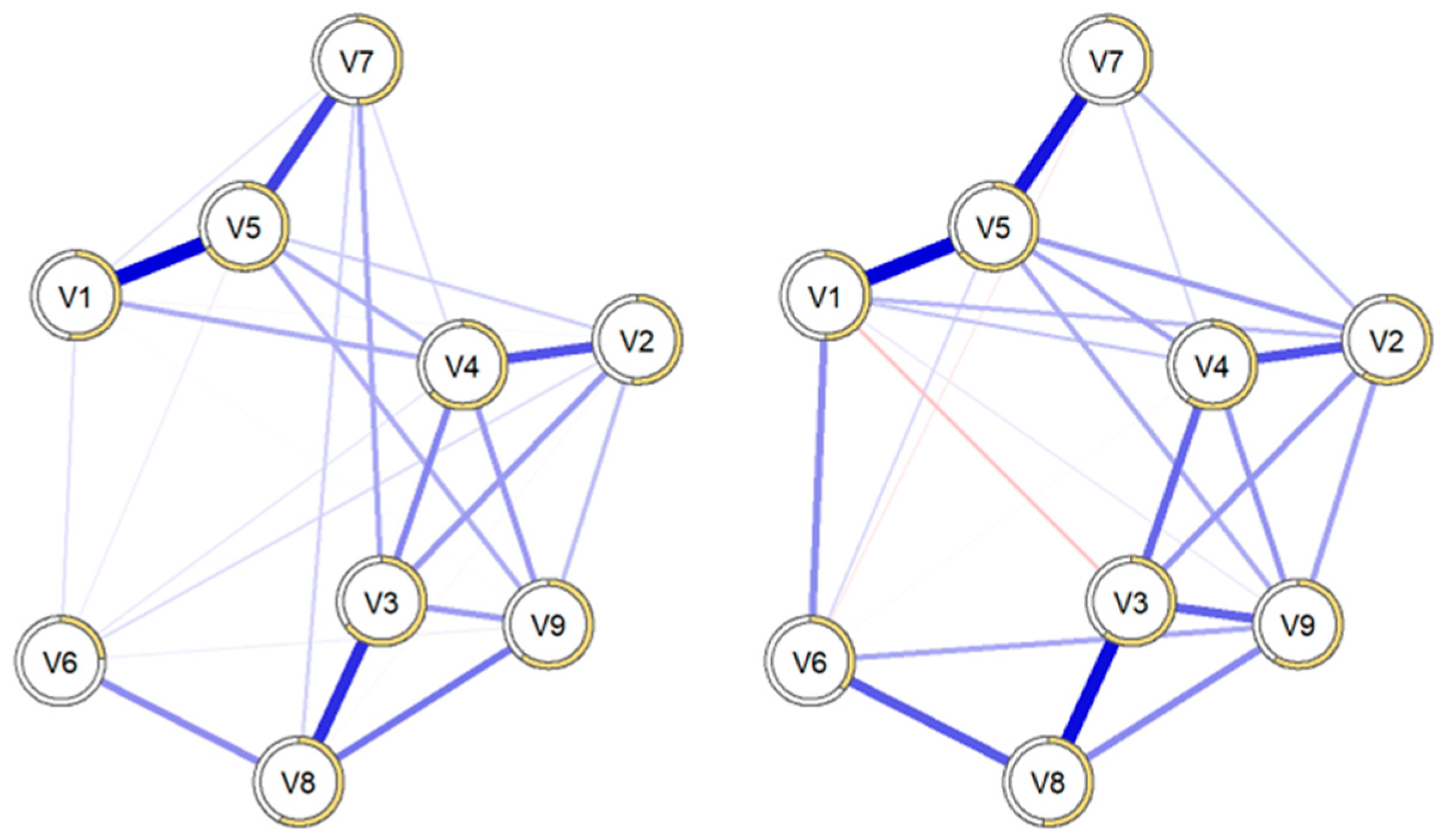

The main objective of this study was to analyze in an outpatient setting how psychopathological networks are configured in individuals with suicidal ideation and to explore the differences compared with those without suicidal ideation.

The initial bivariate contrasts confirmed that there were significant differences in symptoms between the two groups. As expected, patients with suicidal ideation presented more intense psychopathological symptoms at the start of therapy. This finding is consistent with much of the literature, which indicates a strong relationship between the presence of psychological disorders and the likelihood of experiencing suicidal ideation, attempts, and behaviors (

May & Klonsky, 2016;

San Too et al., 2019). Although the scores were consistently higher in all dimensions evaluated, depressive symptoms were clearly more pronounced in the suicidal ideation group (2.26 versus 1.40). However, what stood out the most were the significant differences in the dimensions of interpersonal susceptibility and hostility. Both dimensions have a strong relational component, suggesting that social factors play a key role in this phenomenon (

Barker et al., 2022;

Chu et al., 2017;

Coppersmith et al., 2022;

McClelland et al., 2020).

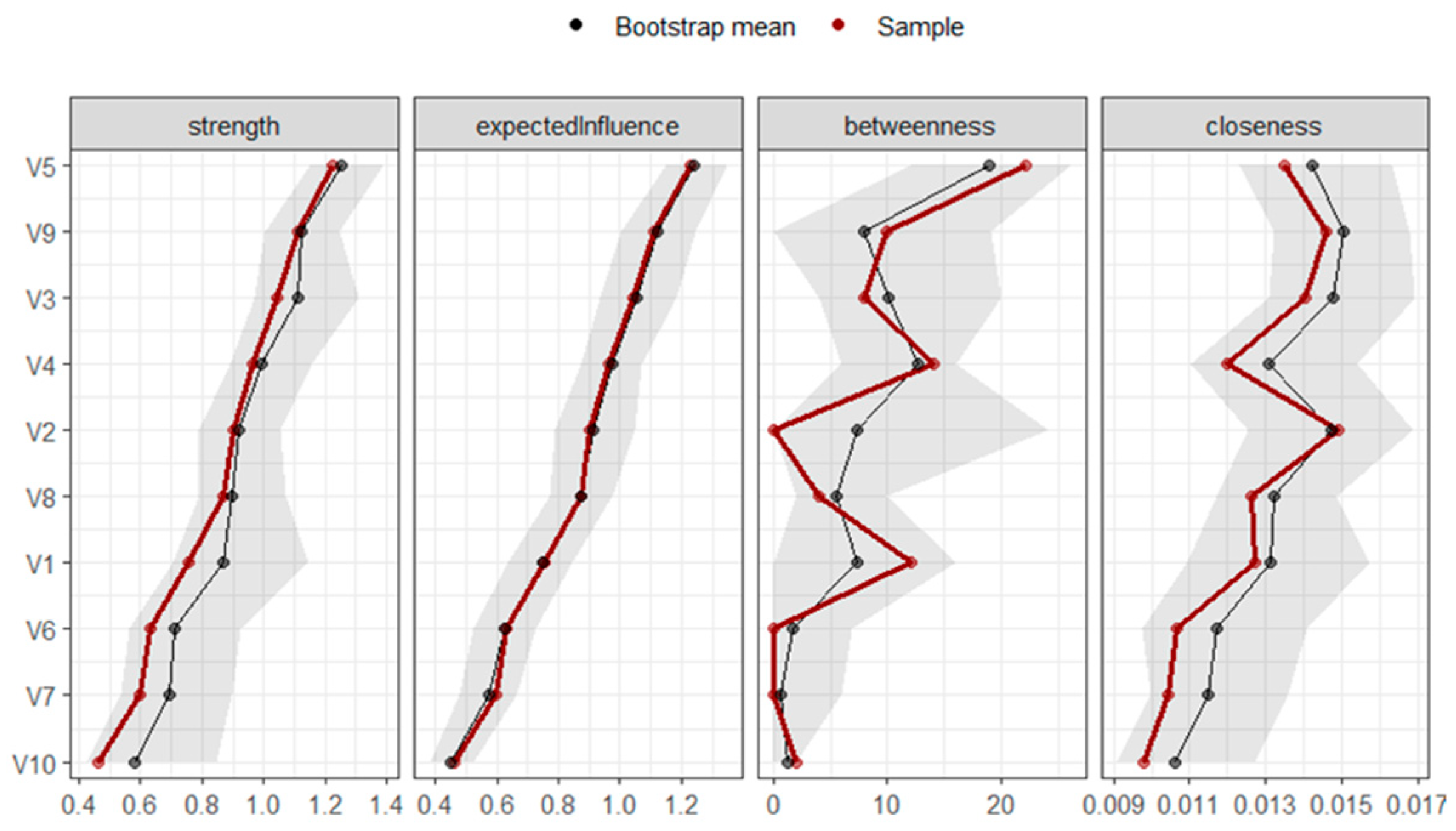

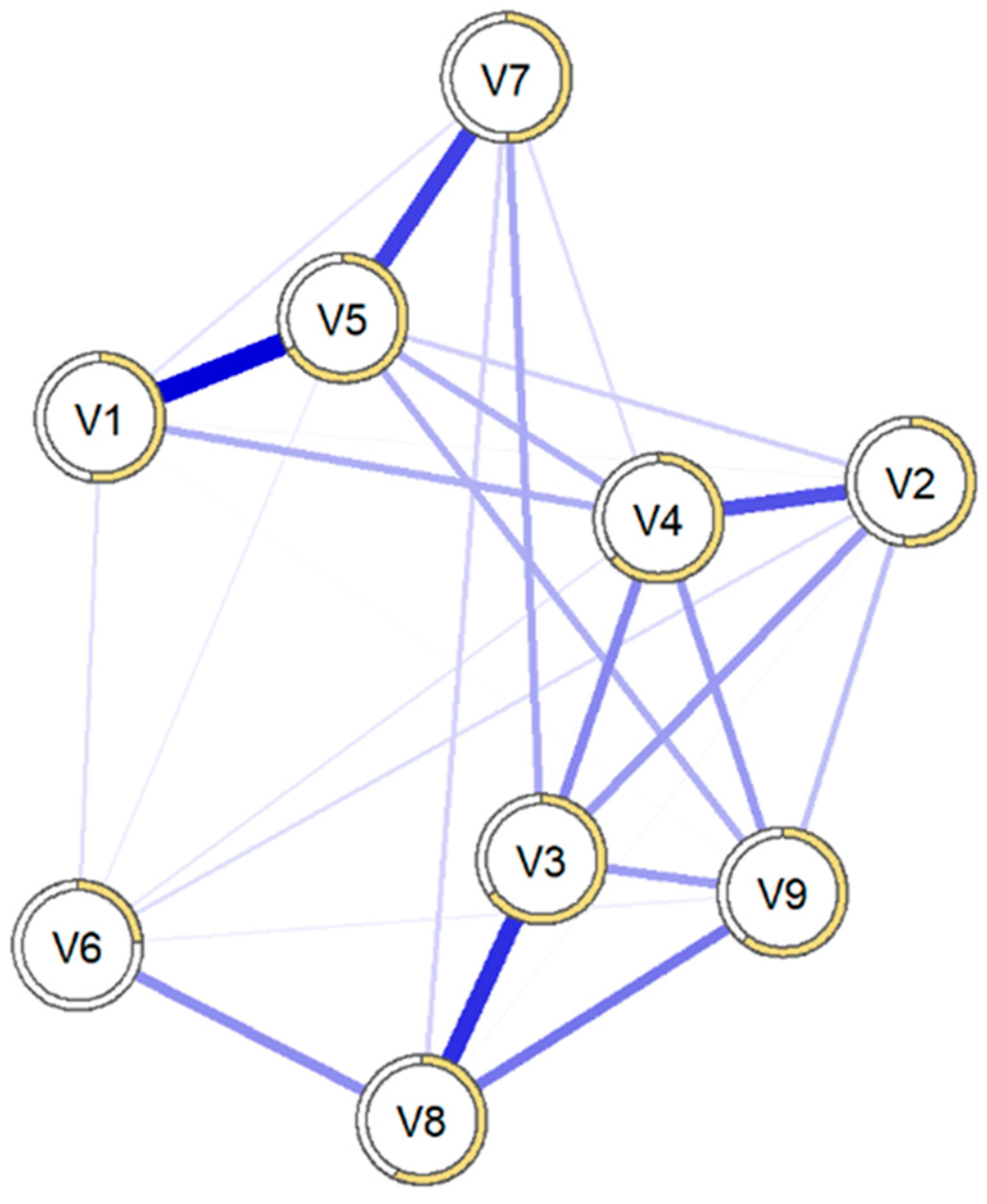

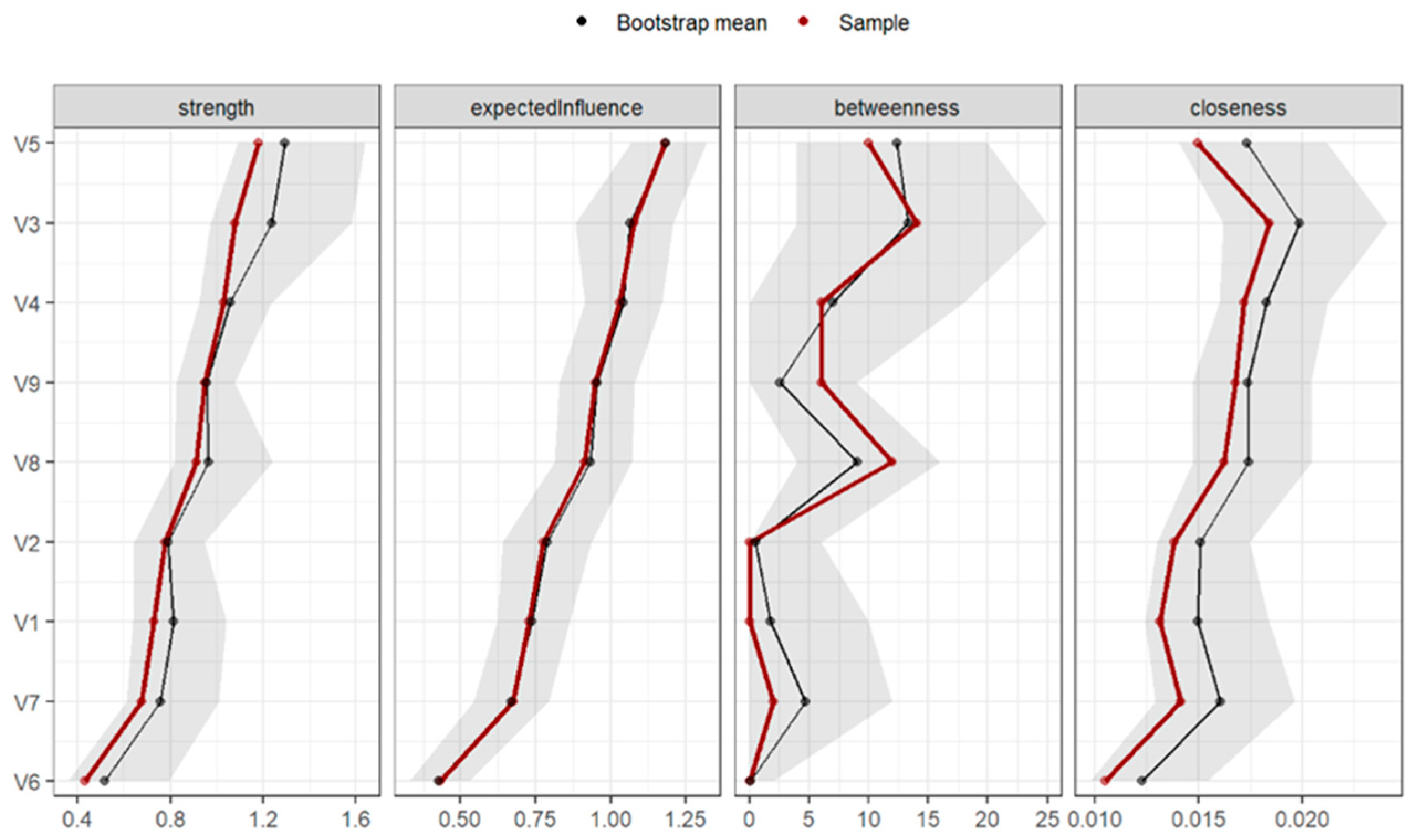

The results of the network analysis for the general sample showed that the most central symptoms for individuals in a clinical outpatient context were depression, anxiety, interpersonal susceptibility, and thoughts of social alienation. However, when analyzing only the network for individuals with suicidal ideation, the most central symptoms were anxiety, thoughts of social alienation, and interpersonal susceptibility. The most central node in terms of centrality strength and expected influence was anxiety, above other symptoms traditionally associated with suicidal behavior, such as depression (

D. De Beurs et al., 2019;

Franklin et al., 2017). This suggests that anxious symptoms are strongly connected to other symptoms and may represent key targets for clinical attention (

McNally et al., 2015), although the cross-sectional nature of the data precludes assumptions about influence or directionality. This finding aligns with the logic of undirected network models, where changes in one symptom may be reflected in related symptoms; however, this study does not provide evidence of causal or directional effects. The fact that anxiety occupies such a central position further reinforces the idea that it is a highly disruptive process (

Stanley et al., 2018) with wide-ranging implications across different areas of the individual (

Olatunji et al., 2007), particularly in the population with suicidal ideation. In fact, anxious traits were also central in a recent network analysis study on suicidal ideation and emotional lability, aligning with the findings of this study. These authors (

Núñez et al., 2020) proposed new hypotheses on how anxiety could lead to depression, rather than depression leading to anxious symptoms, as suggested by other studies (

Cramer et al., 2010).

These findings connect directly with the current transdiagnostic view of psychological disorders. While the relationship with depressive disorders is clear (

Beard et al., 2016;

Casey et al., 2008), the psychological factors contributing to the development of suicidal ideation go beyond depressive symptoms (

Klonsky et al., 2016). This was evident in the dimensions with high centrality, such as psychoticism and interpersonal susceptibility. Some items related to psychoticism, such as “Feeling lonely even when I am with others” and “Feeling always distant, with no sense of intimacy with anyone”, and items related to interpersonal susceptibility, such as “Feeling that others don’t understand me” and “Feeling inferior to others”, are considered clear risk factors for the development of suicidal ideation (

Klonsky & May, 2015;

Van Orden et al., 2010). These symptoms affect key risk factors such as sense of disconnection and loneliness, which again highlights the importance of the social component in this phenomenon.

This point is particularly relevant when interpreting psychometric tests in clinical settings, such as the SCL-90-R. These instruments are frequently used as screening tests in initial evaluations to help guide intervention, but suicidal risk can be overlooked if the connections between other dimensions not traditionally linked to suicide are not established.

The comparison between the psychopathological networks of individuals with and without suicidal ideation yielded unexpected conclusions. Statistically significant differences in the network configuration between the two groups were not observed. Contrarily to expectations, although patients with suicidal ideation had more intense symptoms across all psychopathological dimensions, the relationships between these dimensions were very similar in both groups.

This result suggests that, in clinical outpatient settings, although the initial severity of symptoms is greater in patients with suicidal ideation, the dimensions affected and the relationships between them are similar to those of individuals without ideation. This finding aligns with the perspective that suicide should not be viewed as a phenomenologically distinct phenomenon, but rather as a consequence of more intense distress, possibly experienced with greater anguish or a sense of being trapped (

O’Connor & Kirtley, 2018). Moreover, this does not contradict the presence of general differentiating factors between the two populations, such as prior diathesis or vulnerability (

Mann et al., 1999) or specific life events related to suicide and acquired capability (

Joiner, 2005). These data reinforce the notion of dimensionality in the phenomenon, both in the suicidal continuum and its multiple manifestations (

Barnow & Linden, 2000;

Joiner et al., 2005;

Sveticic & De Leo, 2012). Although the networks were similar in their structure and associative strength, there was evidence of systematically higher symptom intensity in patients with suicidal ideation.

To generate more evidence regarding the relationship between psychopathology and suicidal ideation, a binary logistic regression analysis was conducted, controlling for age and sex. Depressive symptoms, hostility, somatization, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism emerged as significant predictors of suicidal ideation, explaining 37% of the variance in the final model. The presence of depressive symptoms is consistent with previous studies (

May & Klonsky, 2016;

Tsai et al., 2021). However, the strongest risk factor was hostility, increasing the likelihood of suicidal ideation even after controlling for depressive symptoms. This suggests that hostility contributes uniquely to suicide risk, beyond the effects of depression. The fact that hostility showed such a strong effect highlights the role of interpersonal difficulties in suicidal ideation. This aligns with previous research linking hostility and aggressiveness to suicidal behavior (

Gvion & Apter, 2011;

Gvion & Levi-Belz, 2018;

Lemogne et al., 2011;

Menon et al., 2015), underscoring that suicide risk is not solely a matter of emotional distress but also involves perceived conflicts with others.

Beyond affective and interpersonal dimensions, the model also identified somatization, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism as relevant predictors, suggesting that additional forms of psychological dysregulation may elevate suicide risk through distinct mechanisms. Somatization may reflect unprocessed emotional pain manifested in physical symptoms, contributing to a sense of helplessness and unarticulated suffering that increases suicide vulnerability (

Torres et al., 2021). Paranoid ideation, marked by mistrust and perceived threats from others, may lead to increased social withdrawal and heightened feelings of persecution, thereby reinforcing alienation and a sense of thwarted belongingness (

Joiner, 2005). Finally, psychoticism—characterized by disorganized thinking and perceptual disturbances—may impair reality testing and intensify internal chaos, thereby diminishing coping capacity and increasing suicide risk (

Yates et al., 2019).

While depressive symptoms remain clear predictors of suicidal ideation, these additional domains emphasize the multifaceted nature of suicide risk. Somatic complaints may mask underlying emotional distress, paranoid ideation can reinforce isolation, and psychotic features may erode one’s connection to reality—all factors that intersect with existing explanatory models of suicidal ideation and behavior (

Joiner, 2005;

Klonsky & May, 2015;

O’Connor & Kirtley, 2018;

Van Orden et al., 2010).

It is important to note that network and regression analyses address different, yet complementary, research questions. While network analysis focuses on the interrelations and connectivity between symptoms within a system—highlighting anxiety as a central symptom in this sample—regression models aim to identify which variables independently predict an outcome, in this case, suicidal ideation. The fact that hostility emerged as a significant predictor in the regression analysis does not contradict the centrality of anxiety in the network analysis; rather, it reflects that anxiety may be influential within the network structure, while hostility exerts a stronger predictive effect on suicidal ideation when controlling for other variables. Including both methods allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the psychopathological mechanisms underlying suicidal ideation.

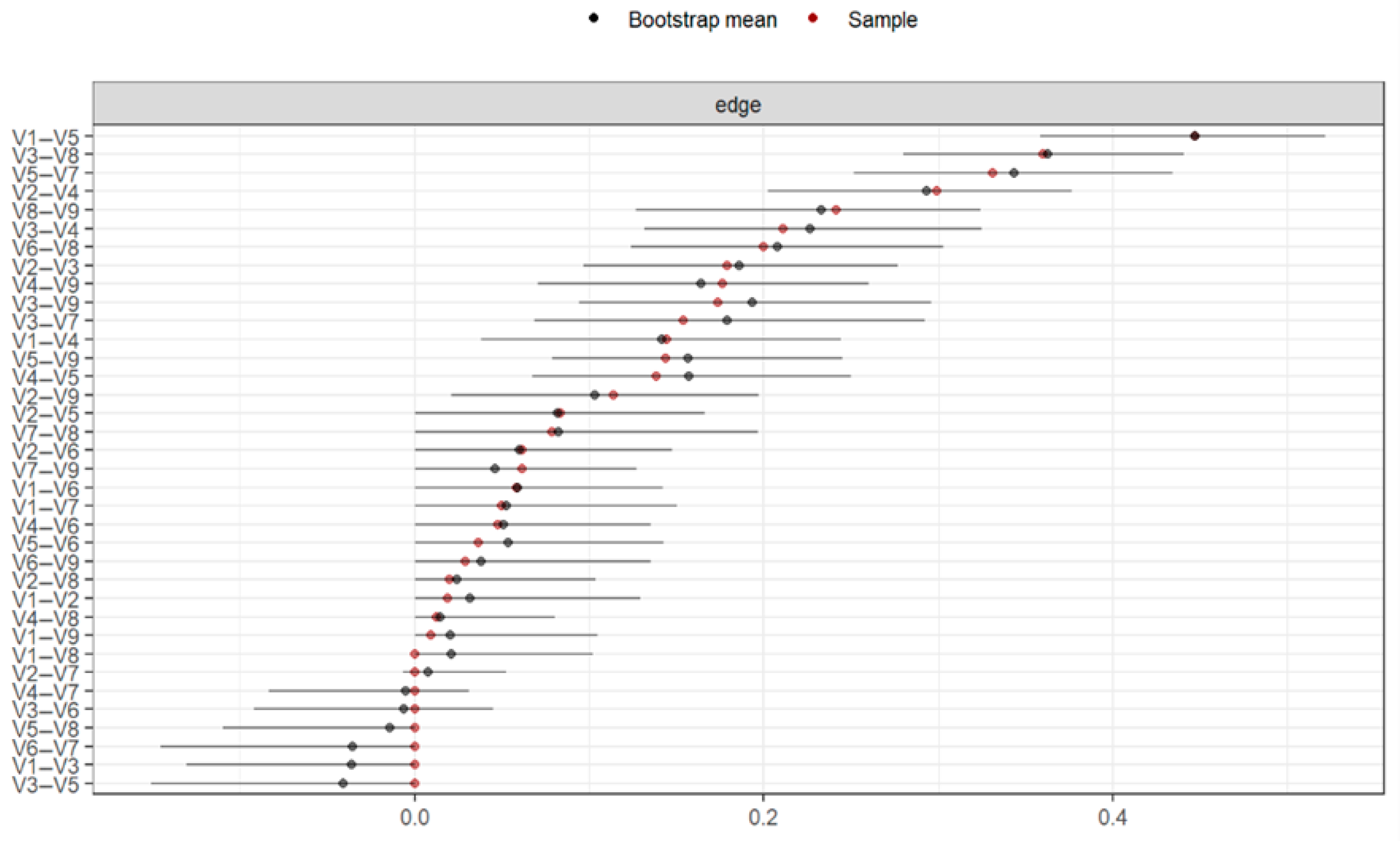

Regarding the limitations of the study, the methodology had certain restrictions due to its developmental stage (

Bringmann & Eronen, 2018;

Brusco et al., 2019;

Guloksuz et al., 2017;

Jones et al., 2017;

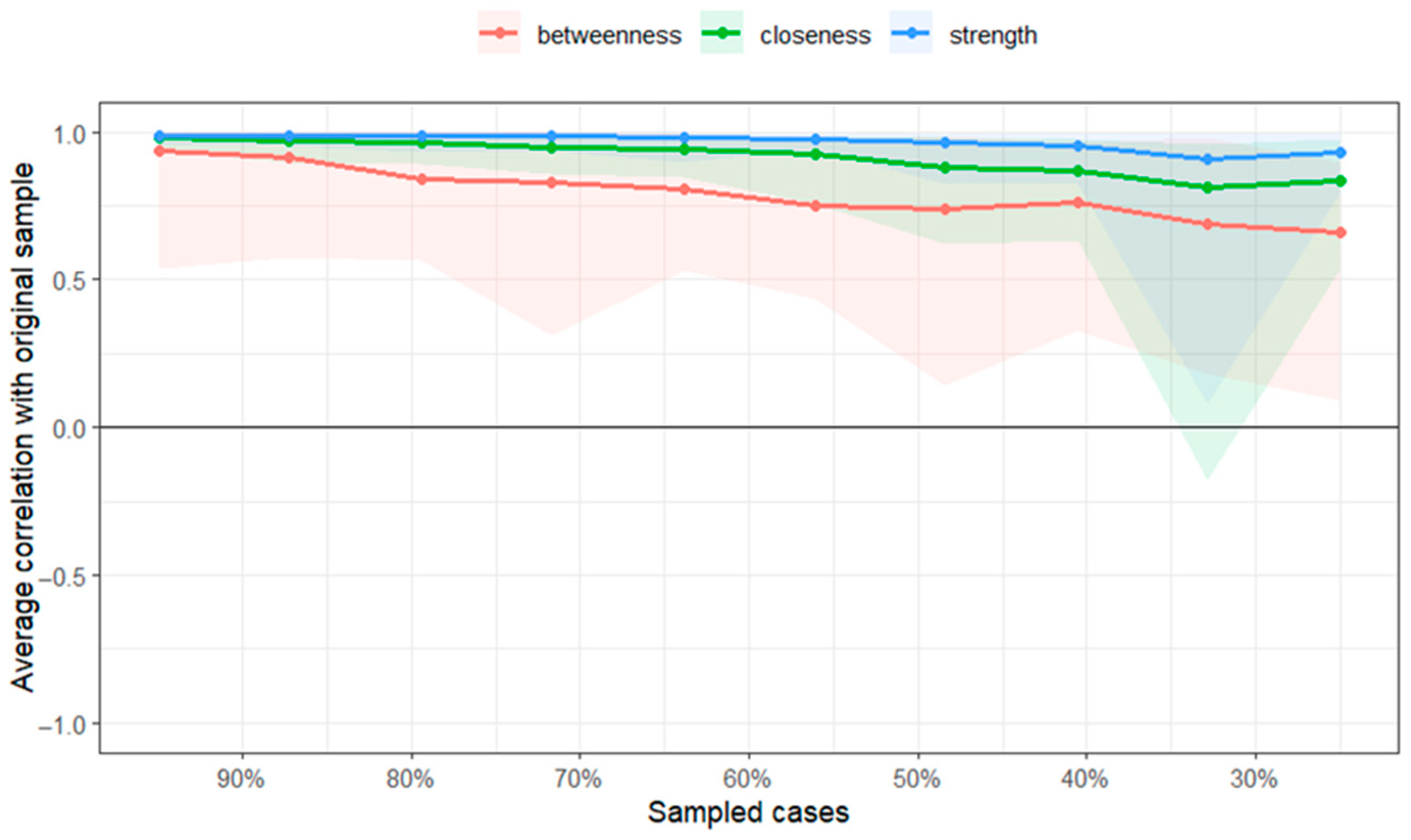

McNally et al., 2017), so the results should be interpreted with caution. Further analyses are needed to address issues related to the stability of the networks, as the current value was above the necessary threshold of 0.50 but below 0.70, which some authors consider adequate (

Bringmann & Eronen, 2018).

The assessment of suicidal ideation at a single time point, without complementary information on prior or future ideation, limits the ability to explore this symptom’s temporal dynamics. This cross-sectional approach constrains interpretations related to the onset, persistence, or fluctuation of suicidal thoughts. Future longitudinal studies or pre-/post-treatment designs would allow for a more nuanced understanding of how suicidal ideation evolves in clinical outpatient populations.

A further concern is the mismatch between the timeframes of the instruments used, specifically, the BDI-II and the SCL-90-R, which assess symptoms over different reference periods. Although this discrepancy is relatively minor, it may have introduced additional measurement variability and complicate direct comparisons between the constructs evaluated by each instrument.

The gender composition of the sample also warrants consideration, with a predominance of women (66%). This imbalance may limit the generalizability of the results to populations with a higher representation of men. However, given the higher prevalence of suicidal ideation among women in epidemiological research, this distribution reflects patterns typically observed in clinical samples and is thus not unexpected in the present context.

A significant constraint lies in the absence of diagnostic data related to specific mental disorders, which prevented subgroup analyses by diagnostic category. This limits the interpretability of how symptom networks may differ according to underlying psychopathological profiles. Similarly, important clinical variables—such as history of suicide attempts, current psychopharmacological treatment, and substance use—were not collected. These factors are recognized as critical in assessing suicidal risk, and their absence reduces the depth and clinical applicability of the findings. Incorporating such variables in future research would enhance the contextualization and relevance of network structures.

An additional methodological issue involves the dichotomization of suicidal ideation based solely on item 9 of the BDI-II. While the use of this item is supported by prior research, and its predictive validity has been established (

Green et al., 2015), this binary classification may lead to loss of nuance and restrict variability within subgroups. The two-week timeframe used may fail to capture individuals with relevant SI histories outside that window. Moreover, the case–control design applied may be subject to Berkson’s bias (

de Ron et al., 2021), potentially affecting the representativeness and robustness of the estimated networks.

Future studies exploring differences in more specific subgroups could establish the dynamics between the dimensions addressed in this study. Furthermore, the implementation of network analysis based on the items of these dimensions could provide a deeper understanding of how they relate to each other and the directions of these relationships. In addition, incorporating complementary assessment tools may help differentiate psychopathological dimensions more precisely and further explore their unique contributions to suicide risk. This approach would ultimately refine the understanding of how specific psychological factors interact in the prediction of suicidal behavior.

Finally, this study provides updated evidence of the suicide phenomenon in clinical care contexts, serving as a starting point and a framework for future research on the subject, overcoming the previously mentioned limitations. This is the first study to use network analysis to examine the psychopathological symptoms of individuals with suicidal ideation in an outpatient clinical setting. Moreover, an important strength of this study is the use of the SCL-90-R, a widely employed instrument in routine clinical practice. This enhances the ecological validity of the findings, as the results are based on a tool frequently used in real-world consultations, making them more applicable to everyday clinical settings. Additionally, it is interesting to note that the distribution of means for the SCL-90-R dimensions in the present study closely resembled the study by

Carrasco et al. (

2003), highlighting the symptomatic similarities between clinical outpatient contexts, despite the time that has elapsed, and providing us with an updated reference of the main dimensions affected in a clinical outpatient context. Although the findings should be generalized cautiously to other populations, they have relevant clinical implications. Understanding how psychopathological symptoms relate to suicidal ideation, as well as the relevance of anxious and interpersonal symptoms in configuring the psychopathological networks of suicidal patients, can assist therapists in their evaluations/interventions and provide a therapeutic target for the “deactivation” of adjacent symptoms causing distress to the person. Furthermore, by using item 9 of the BDI-II, which assesses suicidal ideation within the past two weeks, the study deliberately focused on active or current suicidal ideation. This temporal frame enhances the clinical utility of the findings, as it allows for the identification of proximal risk factors and supports timely intervention in routine practice.