Unfinished Tasks and Unsettled Minds: A Diary Study on Personal Smartphone Interruptions, Frustration, and Rumination

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aims and Contributions

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. The Smartphone as a Tool to Manage Multiple Roles

2.2. The Experience of Feeling Interrupted by Personal Smartphone Use During Worktime

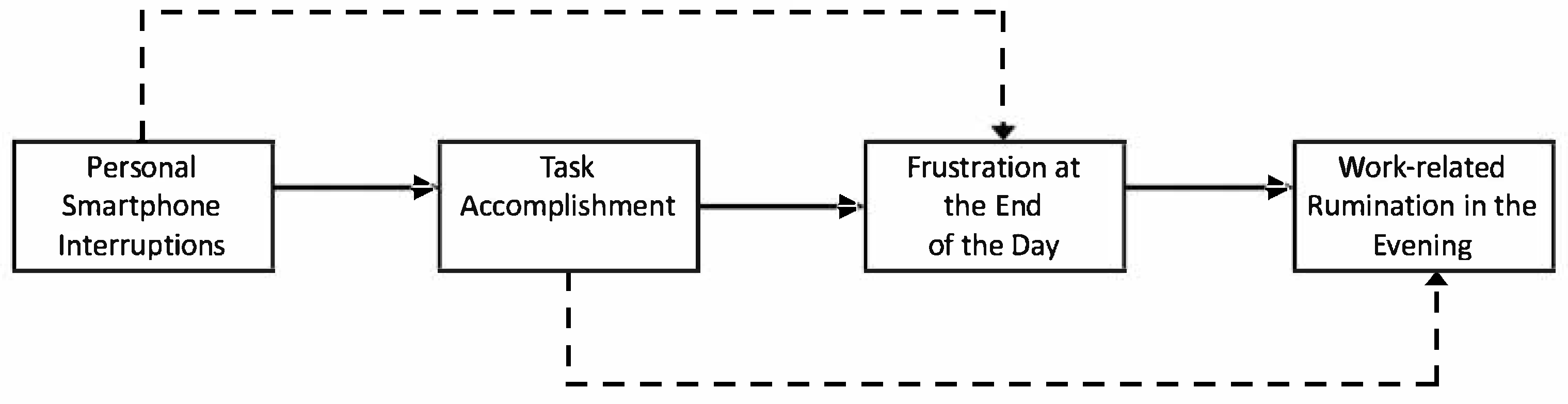

2.3. Daily Smartphone Interruptions, Task Accomplishment, and Frustration

2.4. Frustration as an Explanatory Mechanism in the Relationship Between Task Accomplishment and Work-Related Rumination

3. Method

3.1. Procedure and Participants

3.2. Measurement Instruments

3.3. Strategy of Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptives Statistics

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions and Practical Implications

5.1.1. Extending the Rumination Literature

5.1.2. Affective and Cognitive Pathways in Interruption Research

5.1.3. Managing Personal Smartphone Use to Enhance Workplace Focus

5.1.4. Organizational Strategies for Managing Personal Smartphone Use

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5.2.1. Study Design and Measurement Constraints

5.2.2. Contextual and Temporal Factors

5.2.3. Underlying Motivations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Addas, S., & Pinsonneault, A. (2015). The many faces of information technology interruptions: A taxonomy and preliminary investigation of their performance effects. Information Systems Journal, 25, 231–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T. D., Merlo, K., Lawrence, R. C., Slutsky, J., & Gray, C. E. (2021). Boundary management and work-nonwork balance while working from home. Applied Psychology, 70(1), 60–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C., Heinisch, J. S., Ohly, S., David, K., & Pejovic, V. (2019). The impact of private and work-related smartphone usage on interruptibility. In Adjunct proceedings of the 2019 ACM international Joint conference on pervasive and ubiquitous computing and proceedings of the 2019 ACM international symposium on wearable computers (UbiComp/ISWC ‘19 Adjunct) (pp. 1058–1063). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C. S., Torsheim, T., & Pallesen, S. (2014). Use of online social network sites for personal purposes at work: Does it impair self-reported performance? Comprehensive Psychology, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B. E., Kreiner, G. E., & Fugate, M. (2000). All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Academy of Management Review, 25, 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethge, A., & Rigotti, T. (2010). Arbeitsunterbrechungen und multitasking (Work Interruptions and Multitasking). BAUA. [Google Scholar]

- Baethge, A., & Rigotti, T. (2013). Interruptions to workflow: Their relationship with irritation and satisfaction with performance, and the mediating roles of time pressure and mental demands. Work & Stress, 27(1), 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethge, A., Rigotti, T., & Roe, R. A. (2015). Just more of the same, or different? An integrative theoretical framework for the study of cumulative interruptions at work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(2), 308–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, B. P., & Konstan, J. A. (2006). On the need for attention-aware systems: Measuring effects of interruption on task performance, error rate, and affective state. Computers in Human Behavior, 22(4), 685–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, B. J. (1986). Recent developments in role-theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 12(1), 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, J. E., Glomb, T. M., Shen, W., Kim, E., & Koch, A. J. (2013). Building positive resources: Effects of positive events and positive reflection on work stress and health. Academy of Management Journal, 56(6), 1601–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carton, A. M., & Aiello, J. R. (2009). Control and anticipation of social interruptions: Reduced stress and improved task performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 39(1), 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1990). Origins and functions of positive and negative affect: A control-process view. Psychological Review, 97(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A., & Karahanna, E. (2014). Boundaryless technology: Understanding the effects of technology-mediated interruptions across the boundaries between work and personal life. AIS Transactions on Human-Computer Interaction, 2, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P. Y., & Spector, P. E. (1992). Relationships of work stressors with aggression, withdrawal, theft and substance use: An exploratory study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 65, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropley, M., Michalianou, G., Pravettoni, G., & Millward, L. J. (2012). The relation of post-work ruminative thinking with eating behaviour. Stress Health, 28, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropley, M., & Zijlstra, F. R. H. (2011). Work and rumination. In J. Langan-Fox, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Handbook of stress in the occupations. Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Delanoeije, J., & Verbruggen, M. (2019). The use of work-home practices and work-home conflict: Examining the role of volition and perceived pressure in a multi-method study. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanoeije, J., Verbruggen, M., & Germeys, L. (2019). Boundary-role transitions: A day-to-day approach to explain the effects of home-based telework on work-to-home conflict and home-to-work conflict. Human Relations, 72(12), 1843–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. (2017). Global mobile consumer survey 2017, NL edition. Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/global/en/Industries/tmt/perspectives/gx-global-mobile-consumer-trends.html (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Derks, D., Bakker, A. B., & Gorgievski, M. (2021). Private smartphone use during worktime: A diary study on the unexplored costs of integrating the work and family domains. Computers in Human Behavior, 114, 106530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, D., Van Duin, D., Tims, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2015). Smartphone use and work-home interference: The moderating role of social norms and employee work engagement. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, É., & Montag, C. (2017). Smartphone addiction, daily interruptions and self-reported productivity. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 6, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eatough, E. M., Meier, L. L., Igic, I., Elfering, A., Spector, P. E., & Semmer, N. K. (2016). You want me to do what? Two daily diary studies of illegitimate tasks and employee well-being. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A. S., Diefendorff, J. M., & Erickson, R. J. (2011). The relations of daily task accomplishment satisfaction with changes in affect: A multilevel study in nurses. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(5), 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hacker, W. (2005). Allgemeine Arbeitspsychologie—Psychische regulation von wissens-, denk- and körperlich arbeit (2nd ed.). General Industrial Psychology—Mental Regulation of Knowledge Work, Mental Work and Physical Work. Huber. [Google Scholar]

- Heitmayer, M. (2025). When the phone’s away, people use their computer to play: Distance to the smartphone reduces device usage but not overall distraction and task fragmentation during work. Frontiers in Computer Science, 7, 1422244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X. J., Barber, L. K., Park, Y., & Day, A. (2021). Defrag and reboot? Consolidating information and communication technology research in IO psychology. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 14(3), 371–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, E. M., Clark, M. A., & Carlson, D. S. (2019). Violating work-family boundaries: Reactions to interruptions at work and home. Journal of Management, 45(3), 1284–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R., Schwind, K. M., Wagner, D. T., Johnson, M. D., DeRue, D. S., & Ilgen, D. R. (2007). When can employees have a family life? The effects of daily workload and affect on work-family conflict and social behaviors at home. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(5), 1368–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jett, Q. R., & George, J. M. (2003). Work interrupted: A closer look at the role of interruptions in organizational life. Academy of Management Review, 28, 494–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, U., Feldt, T., de Bloom, J., Sianoja, M., Korpela, K., & Geurts, S. (2017). Linking boundary crossing from work to nonwork to work-related rumination across time: A variable-and person-oriented approach. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(4), 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konradt, U., Hertel, G., & Schmook, R. (2003). Quality of management by objectives, task-related stressors and non-task related-stressors as predictors of stress and job satisfaction among teleworkers. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 12, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E. E., Ruderman, M. N., Braddy, P. W., & Hannum, K. M. (2012). Work-nonwork boundary management profiles: A person-centered approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiner, G. E., Hollensbe, E. C., & Sheep, M. L. (2009). Balancing borders and bridges: Negotiating the work-home interface via boundary work tactics. Academy of Management Journal, 52, 704–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushlev, K., & Dunn, E. W. (2015). Checking email less frequently reduces stress. Computers in Human Behavior, 43, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühner, C., Rudolph, C. W., Derks, D., Posch, M., & Zacher, H. (2023). Technology-assisted supplemental work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 142, 103861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, S. (2009). Why is it so hard to do my work? The challenge of attention residu when switching between work tasks. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 109(2), 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, S., & Glomb, T. M. (2018). Tasks interrupted: How anticipating time pressure on resumption of an interrupted task causes attention residue and low performance on interrupting tasks and how a “ready-to-resume” plan mitigates the effects. Organization Science, 29(3), 380–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, S., Schmidt, A. M., & Madjar, N. (2020). Interruptions and task transitions: Understanding their characteristics, processes, and consequences. Academy of Management Annals, 14(2), 661–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B. C., Kain, J. M., & Fritz, C. (2013). Don’t interrupt me! An examination of the relationship between intrusions at work and employee strain. International Journal of Stress Management, 20(2), 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J., Kerulis, A. M., Wang, Y., & Sachdev, A. (2020). Are workflow interruptions a hindrance stressor? The moderating effect of time-management skill. International Journal of Stress Management, 27(3), 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, G., Gudith, D., & Klocke, U. (2008, April 5–10). The cost of interrupted work: More speed and stress. CHI ‘08: SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 107–110), Florence, Italy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marulanda-Carter, L., & Jackson, T. W. (2012). Effects of e-mail addiction and interruptions on employees. Journal of Systems and Information Technology, 14, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messenger, J., & Gschwind, L. (2016). Three generations of telework: New ICTs and the (R)evolution from home office to virtual office. New Technology, Work and Employment, 31(3), 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montag, C., Duke, E., & Markowetz, A. (2016). Toward psychoinformatics: Computer science meets psychology. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine, 2016, 2983685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, W., Nordberg, T., Drange, I., Junker, N. M., Aksnes, S. Y., Cooklin, A., Cho, E., Habib, L. M. A., Hokke, S., Olson-Buchanan, J. B., & Bernstrøm, V. H. (2024). Boundary-crossing ICT use–A scoping review of the current literature and a road map for future research. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 15, 100444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, S., & Bastin, L. (2023). Effects of task interruptions caused by notifications from communication applications on strain and performance. Journal of Occupational Health, 65(1), e12408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, S., & Schmitt, A. (2015). What makes us enthusiastic, angry, feeling at rest or worried? Development and validation of an affective work events taxonomy using concept mapping methodology. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30(1), 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oulasvirta, A., Rattenbury, T., Ma, L., & Raita, E. (2012). Habits make smartphone use more pervasive. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 16(1), 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterer, A. S., Yanagida, T., Kühnel, J., & Korunka, C. (2021). Staying in touch, yet expected to be? A diary study on the relationship between personal smartphone use at work and work–nonwork interaction. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 94(3), 735–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, L. H., O’Connor, E. J., & Rudolf, C. J. (1980). The behavioral and affective consequences of performance-relevant situational variables. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 25(1), 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puranik, H., Koopman, J., & Vough, H. C. (2020). Pardon the interruption: An integrative review and future research agenda for research on work interruptions. Journal of Management, 46(6), 806–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramarajan, L., & Reid, E. (2013). Shattering the myth of separate worlds: Negotiating nonwork identities at work. Academy of Management Review, 38, 621–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashbash, J., Browne, W., Healy, M., Cameron, B., & Charlton, C. (2000). MLwiN (version 1.10.006). Interactive software of multi-level analysis. Multilevel Models Project, Institute of Education, University of London. [Google Scholar]

- Reyt, J., & Wiesenfeld, B. M. (2015). Seeing the forest for the trees: Exploratory learning, mobile technology, and knowledge workers’ role integration behaviors. Academy of Management Journal, 58, 739–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, B. W. (2016). Successfully leaving work at work: The self-regulatory underpinnings of psychological detachment. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 89(3), 493–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S. (2011). Recovery from fatigue: The role of psychological detachment. In P. L. Ackerman (Ed.), Cognitive fatigue: Multidisciplinary perspectives on current research and future applications. decade of behaviour/science conference (pp. 253–272). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnentag, S., & Bayer, U.-V. (2005). Switching off mentally: Predictors and consequences of psychological detachment from work during off-job time. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10(4), 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2007). The Recovery Experience Questionnaire: Development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(3), 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2015). Recovery from job stress: The stressor-detachment model as an integrative framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(S1), S72–S103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S., Reinecke, L., Mata, J., & Vorderer, P. (2018). Feeling interrupted—Being responsive: How online messages relate to affect at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrek, C. J., Weigelt, O., Pfeifer, C., & Antoni, C. H. (2017). Zeigarnik’s sleepless nights: How unfinished tasks at the end of the week impair employee sleep on the weekend through rumination. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(2), 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahle-Hinz, T., Mauno, S., de Bloom, J., & Kinnunen, U. (2017). Rumination for innovation? Analysing the longitudinal effects of work-related rumination on creativity at work and off-job recovery. Work & Stress, 31(4), 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaziri, H., Casper, W. J., Wayne, J. H., & Matthews, R. A. (2020). Changes to the work–family interface during the COVID-19 pandemic: Examining predictors and implications using latent transition analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(10), 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M., Shaffer, M. A., Lau, T., & Cheung, E. (2019). The knife cuts on both sides: Examining the relationship between cross-domain communication and the work-family interface. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92, 978–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherbee, T. G. (2010). Counterproductive use of technology at work: Information and communications technologies and cyberdeviancy. Human Resource Management Review, 20, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigelt, O., Gierer, P., & Syrek, C. J. (2019a). My mind is working overtime—Towards an integrative perspective of psychological detachment, work-related rumination, and work reflection. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(16), 2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigelt, O., Syrek, C. J., Schmitt, A., & Urbach, T. (2019b). Finding peace of mind when there still is so much left undone—A diary study on how job stress, competence need satisfaction, and proactive work behavior contribute to work-related rumination during the weekend. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(3), 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory. Research in Organizational Behavior, 18(1), 1–74. Available online: https://web.mit.edu/curhan/www/docs/Articles/15341_Readings/Affect/AffectiveEventsTheory_WeissCropanzano.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Wendsche, J., & Lohmann-Haislah, A. (2017). A meta-analysis on antecedents and outcomes of detachment from work. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wöhrmann, A. M., & Ebner, C. (2021). Understanding the bright side and the dark side of telework: An empirical analysis of working conditions and psychosomatic health complaints. New Technology, Work and Employment, 36(3), 348–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | Std. | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Gender (0 = male, 1 = female) | 0.58 | 0.49 | - | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.04 | −0.45 *** | −0.11 | |

| 2. Age | 31.60 | 13.09 | −0.18 ** | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 3. Smartphone interruptions | 2.07 | 1.06 | 0.03 | −0.09 | 0.10 | −0.11 * | 0.20 *** | 0.13 * | −0.07 | |

| 4. Frustration | 3.03 | 1.28 | 0.07 | −0.20 ** | 0.15 ** | −0.20 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.11 ** | −0.15 *** | |

| 5. Task accomplishment | 3.94 | 0.78 | 0.03 | −0.13 * | −0.14 ** | −0.29 ** | −0.24 *** | −0.05 | 0.12 * | |

| 6. Affective rumination | 2.07 | 1.01 | 0.03 | −0.13 * | 0.24 ** | 0.51 ** | −0.21 ** | 0.35 *** | −0.32 *** | |

| 7. PS pondering | 2.77 | 0.91 | −0.25 ** | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.13 * | −0.07 | 0.38 ** | −0.27 *** | |

| 8. Psychological detachment | 3.27 | 0.71 | 0.09 | 0.03 | −0.05 | −0.29 ** | 0.19 ** | −0.46 ** | −0.37 ** |

| Affective Rumination | Problem-Solving Pondering | Psychological Detachment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor Model | Predictor Model | Predictor Model | ||||

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Intercept | 2.08 *** | 0.08 | 3.03 *** | 0.10 | 3.26 *** | 0.05 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Gender | −0.45 ** | 0.14 | ||||

| Task accomplishment | −0.24 ** | 0.07 | −0.05 | 0.07 | 0.12 * | 0.06 |

| Variance level 2 (employee) | 0.39 (40%) | 0.08 | 0.28 (37%) | 0.06 | 0.13 (26%) | 0.04 |

| Variance level 1 (day) | 0.58 (60%) | 0.05 | 0.48 (63%) | 0.04 | 0.37 (74%) | 0.03 |

| −2 Log likelihood | 922.055 | 847.893 | 728.596 | |||

| Affective Rumination | Problem-Solving Pondering | Psychological Detachment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor Model | Predictor Model | Predictor Model | ||||

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Intercept | 2.08 *** | 0.08 | 3.03 *** | 0.10 | 3.26 *** | 0.05 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Gender | −0.45 ** | 0.14 | ||||

| Frustration | 0.29 *** | 0.04 | 0.11 ** | 0.04 | −0.15 *** | 0.04 |

| Variance level 2 (employee) | 0.41 (45%) | 0.08 | 0.28 (38%) | 0.06 | 0.14 (29%) | 0.04 |

| Variance level 1 (day) | 0.51 (55%) | 0.04 | 0.47 (62%) | 0.04 | 0.35 (71%) | 0.03 |

| −2 Log likelihood | 888.887 | 841.248 | 716.145 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Derks, D.; van Mierlo, H.; Kühner, C. Unfinished Tasks and Unsettled Minds: A Diary Study on Personal Smartphone Interruptions, Frustration, and Rumination. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 871. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070871

Derks D, van Mierlo H, Kühner C. Unfinished Tasks and Unsettled Minds: A Diary Study on Personal Smartphone Interruptions, Frustration, and Rumination. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):871. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070871

Chicago/Turabian StyleDerks, Daantje, Heleen van Mierlo, and Clara Kühner. 2025. "Unfinished Tasks and Unsettled Minds: A Diary Study on Personal Smartphone Interruptions, Frustration, and Rumination" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 871. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070871

APA StyleDerks, D., van Mierlo, H., & Kühner, C. (2025). Unfinished Tasks and Unsettled Minds: A Diary Study on Personal Smartphone Interruptions, Frustration, and Rumination. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 871. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070871