Online Song Intervention Program to Cope with Work Distress of Remote Dispatched Workers: Music for an Adaptive Environment in the Hyperconnected Era

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Does the online song therapy intervention help participants better cope with work-related stressors?

- How does the intervention foster psychological resilience through relationship building, autonomy, and emotional regulation.

- What key changes in participants’ psychological processes emerged during and after the intervention?

- How can participants use the song resource in their work environment?

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.2.1. Intake for Participants Psychological Needs and Therapy Readiness

2.2.2. Development of Song Intervention Program

2.2.3. Participation Format for the Program

2.2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Sample Session Application Plan for Song Intervention and Objectives

| Session Flow | Therapist Guiding and Use of Song | Objectives |

| Checking-In |

| Focus here and now |

| Identifying | Focus on the difficult feelings from the past week | Identify personal challenges |

| Connecting |

| Explore inner resources that may be of help |

| Formulate the group support | |

| Song listening |

| Develop personal music resource |

| Project their issues to the lyrics presented | |

| Resourcing |

| Internalize the psychological strength from the lyric |

| Reaffirming |

| Formulate support and connection for commonality and empathy |

Appendix B. Selected Songs for Sessions

| Sessions | Name of Songs | Singer | Major Theme or Message | CSM-Related Concept |

| 1 | There is a canteen beside the cloud | Liming Wang | The song describes a small village located on the edge of the clouds and a canteen in it, as well as the people and things closely connected with it. | Assessment |

| Blue Lotus | Xu wei | encourages listeners to reflect on the meaning of life, confront difficulties with bravery, and pursue freedom and ideals. | Motivation | |

| 2 | My Decimate | Lao Lang | The song is known for its gentle, beautiful, and touching melody, making it a notable piece in the genre of folk music. | Relationship |

| I Believe So | Jay Chou | Whether it is his firm belief in love or his positive attitude towards life, they are all conveyed vividly through his singing. | Self-efficacy | |

| 3 | Friends | Zhou Huajian | The lyrics emphasize the importance of friends accompanying each other in life and facing difficulties together, allowing the audience to feel the warmth and strength of friendship when listening. | Relationship |

| I Believe | Yang He’an | The lyrics of “I Believe” are filled with steadfast faith and hope for the future. They convey the message of pursuing dreams, overcoming obstacles, and anticipating a bright future. | Self-efficacy | |

| 4 | Push the Door to the World | Huoxing diantai | The lyrics describe the courage and determination to face the unknown world and are full of philosophy and exploration spirit. | Self-efficacy |

| A Journey to the Mountain | Mao buyi | The metaphor of a mountain road represents the journey of perseverance—each steep climb fuels your motivation, every summit reached strengthens your resolve, and the breathtaking view at the top reminds you why the struggle was worth it. | Motivation |

References

- Ansdell, G. (2016). How music helps in music therapy and everyday life. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Arduman, E. (2021). Anxiety, uncertainty, and resilience during the pandemic: “Re-directing the gaze of the therapeutic couple”. In Anxiety, uncertainty, and resilience during the pandemic period-anthropological and psychological perspectives. IntechOpen. [Google Scholar]

- Avey, J. B., Luthans, F., & Jensen, S. M. (2009). Psychological capital: A positive resource for combating employee stress and turnover. Human Resource Management, 48(5), 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradt, J., Dileo, C., Myers-Coffman, K., & Biondo, J. (2021). Music interventions for improving psychological and physical outcomes in people with cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, H. J., & Yun, J. (2020). Music therapy for delinquency involved juveniles through tripartite collaboration: A mixed method study. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 589431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, P. (2019). Renewable energy law: An international assessment. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elvers, P. (2016). Songs for the ego: Theorizing musical self-enhancement. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, N., Boyda, D., McFeeters, D., & Galbraith, V. (2021). Patterns of occupational stress in police contact and dispatch personnel: Implications for physical and psychological health. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 94, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardstrom, S. C., & Hiller, J. (2010). Song discussion as music psychotherapy. Music Therapy Perspectives, 28(2), 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, S., & Davidson, J. W. (2019). Music, nostalgia and memory. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hippler, T., Haslberger, A., & Brewster, C. (2017). Expatriate adjustment. In Research handbook of expatriates (pp. 83–105). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschberg, R., Sylvia, L. G., Wright, E. C., Gupta, C. T., McCarthy, M. D., Harward, L. K., Goetter, E. M., Boland, H., Tanev, K., & Spencer, T. J. (2020). Collaborative songwriting intervention for veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 26(3), 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Istvandity, L. (2014). The lifetime soundtrack: Music as an archive for autobiographical memory. Popular Music History, 9(2), 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgensmeier, B. (2012). The effects of lyric analysis and songwriting music therapy techniques on self-esteem and coping skills among homeless adolescents. University of Kansas. [Google Scholar]

- Kerig, P. K., Becker, S. P., & Egan, S. (2010). From internalizing to externalizing: Theoretical models of the processes linking PTSD to juvenile delinquency. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Causes, Symptoms and Treatment, 33, 78. [Google Scholar]

- Kniffin, K. M., Narayanan, J., Anseel, F., Antonakis, J., Ashford, S. P., Bakker, A. B., Bamberger, P., Bapuji, H., Bhave, D. P., & Choi, V. K. (2021). COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. American Psychologist, 76(1), 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauber, D. E., Estes, S., & Sherr, M. E. (2022). Veteran participation in operation song: Exploring resiliency in a songwriting experience. Journal of Veterans Studies, 8(3), 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloch, S., & Trevarthen, C. (2018). The human nature of music. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matshidze, P., & Klu, E. (2016). Songs: An expression of venda women’s emotion. Journal of Psychology, 7(1), 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medic, G., Wille, M., & Hemels, M. E. (2017). Short-and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nature and Science of Sleep, 9, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montello, D. R. (2002). Cognitive map-design research in the twentieth century: Theoretical and empirical approaches. Cartography and Geographic Information Science, 29(3), 283–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, S. (2015). Counterfactuals and causal inference. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Petterson, M., & Loy, D. P. (2008). Comparing the effectiveness of animal interaction, digital music relaxation, and humor on the galvanic skin response of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Implications for recreational therapy. Annual in Therapeutic Recreation, 16, 129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Quirke, B. (2017). Making the connections: Using internal communication to turn strategy into action. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Robb, S. L. (2000). The effect of therapeutic music interventions on the behavior of hospitalized children in isolation: Developing a contextual support model of music therapy. Journal of Music Therapy, 37(2), 118–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, S. L. (2003). Designing music therapy interventions for hospitalized children and adolescents using a contextual support model of music therapy. Music Therapy Perspectives, 21(1), 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, S. L., Story, K. M., Harman, E., Burns, D. S., Bradt, J., Edwards, E., Golden, T. L., Gold, C., Iversen, J. R., Habibi, A., & Johnson, J. K. (2025). Reporting Guidelines for Music-based Interventions checklist: Explanation and elaboration guide. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1552659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senske, J. J. (2008). The potential for music to elicit and facilitate autobiographical memory. Argosy University/Seattle. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, E. A., & Wellborn, J. G. (2019). Coping during childhood and adolescence: A motivational perspective. In Life-span development and behavior (pp. 91–134). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Stige, B. (2017). Where music helps: Community music therapy in action and reflection. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y., & Kim, K. S. (2024). Case study of resource-oriented music listening for stress management in employees on international deployment. Journal of Music and Human Behavior, 21(2), 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Fen, B. W., Zhang, C., & Pi, S. (2024). Transforming music education through artificial intelligence: A systematic literature review on enhancing music teaching and learning. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies, 18(18), 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (N = 18) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | % |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 18 | 100 |

| Female | 0 | 0 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 20–29 | 7 | 38.9 |

| 30–39 | 7 | 38.9 |

| 40–49 | 3 | 16.7 |

| 50 and above | 1 | 5.6 |

| Participant type department | ||

| Technology | 7 | 38.9 |

| Shipping Crew (Cargo loading) | 7 | 38.9 |

| Management | 4 | 22.2 |

| Length of working on the ship (years) | ||

| 4–6 | 9 | 50 |

| 7–9 | 8 | 44.4 |

| 10 and above | 1 | 5.6 |

| Length of time you last worked on board a ship (months) | ||

| 3–4 | 7 | 38.9 |

| 5–6 | 9 | 50 |

| 6 and above | 2 | 11.1 |

| Prior experience of therapy | ||

| Yes | 2 | 11.1 |

| No | 16 | 88.9 |

| Section | Questionnaires |

|---|---|

| Readiness |

|

| Psychological mindedness |

|

| Session No. | Session Objectives | Session Format | Song Lyrics for Resource | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | Group | |||

| 1 | Engage with intrinsic motivation for participation and interest in music | Identify any positive associations related to memories or episodes | Share familiar songs with the group and stories related to them | Songs about personal memories, family issues, hometowns, etc. |

| 2 | Identify songs that reflect ‘here & now’ | Select and reflect on lyrics that depict the present emotions and thoughts | Identify common emotional themes in lyrics shared by the group. | Songs about emotions and thoughts related to life issues, loneliness, homesick, challenges, etc. |

| 3 | Identify music resources for personal (intrinsic) and the group (shared) strength. | Identify personal ‘power’ songs and affirm the ownership | Share songs that promote proactive perspectives on current challenges | Songs expressing commitment, inner strength, self-efficiency, etc. |

| 4 | Use the song resources to create an adaptive environment for sustained motivation | Write empowering personal lyrics to a familiar tune. | Write a group lyrics to cope with current situation to the shared tune. | Song writing for determination, perseverance, and a positive outlook. |

| Components | Sub-Components | Descriptions/Rationale |

|---|---|---|

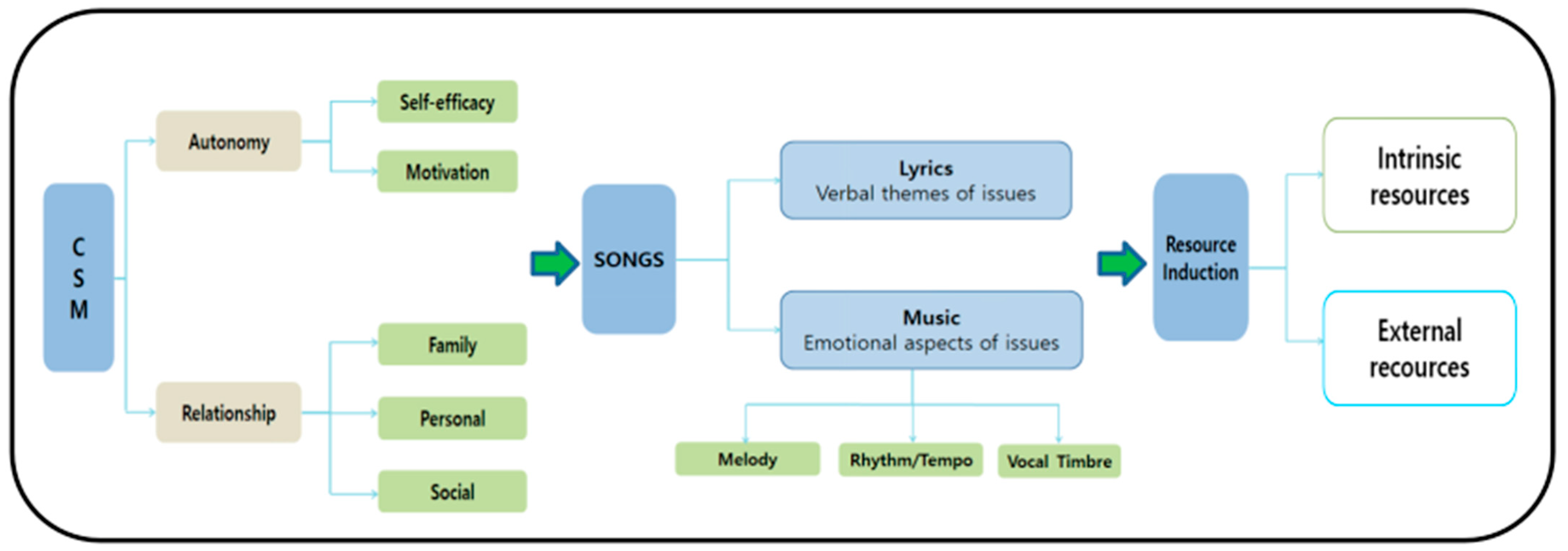

| Intervention Rationale | Theoretical framework | Based on Contextual Support Model concepts: Motivation, self-efficacy, sense of autonomy, psychological resources, interpersonal relationships, etc. |

| Music selection | Selection Rationale | Selected based on the participant’s demographic information, reported familiarity of the song repertoire, session objectives, etc. Lyrics of the selected songs were analyzed for its feasibility and coherence of the session objectives |

| Music Delivery Method | During Session | Played via on-line devices |

| Outside of Session | Personal music playing devices | |

| Materials | Lyrics | Sheet music with lyrics of selected songs are provided |

| Pen/papers for reflection writing | Writing materials for personal song writing | |

| Intervention Strategies | Music listening | Listening to the general mood of the music |

| Song discussion | Discussion of lyrics with target themes and meaning | |

| Interventionist | Primary therapist | Credentialed music therapist |

| Intervention format | Individual and group sessions are provided alternatively each week | Individual and group sessions were provided alternatively to address issues that were personal and relational. In the individual sessions, various personal issues were explored whereas in group sessions, interpersonal issues were shared. |

| Setting | Individual sessions | Participant’s choice of private area such as cabin, where they could use laptop and speakers/microphones. |

| Group sessions | Activity room equipped with big screen and speakers for online program implementation | |

| Intervention Delivery Schedule | Individual sessions | Once a week for 60 min |

| Group Session | Once a week 90 min | |

| Treatment Fidelity | Session report | Each session was recorded and transcribed to collect their verbal statements regarding the song therapy |

| Lyric materials | Participant’s substituted lyrics are collected to analyze personal, emotional and social resources expressed through lyrics. | |

| Post-session Interview | -Session questionnaire: After every session, participants were asked about the lyrics and their current state. -Post-program interview: Individual interviews were conducted after the four-week overall intervention, lasting 30 min per participant. |

| Categories | Sample Questions | |

|---|---|---|

| I | Associations or memories related to the lyric |

|

| II | Messages from the lyrics |

|

| III | Integrate the message of lyrics into daily life |

|

| IV | Owning the song as coping strategy |

|

| Generic Category | Operational Definition | Sample Statement |

|---|---|---|

| Empathy |

|

|

| Consolation |

|

|

| Positive Perspective |

|

|

| Vicarious empowerment |

|

|

| Trust |

|

|

| Change of Attitude |

|

|

| Determination |

|

|

| Anticipation |

|

|

| Motivation |

|

|

| Achievement |

|

|

| Containment |

|

|

| Sedative Centering |

|

|

| Externalization |

|

|

| Ventilation |

|

|

| Subcategory | Generic Category | Main Category |

|---|---|---|

| Empathy | Support system | Relationship |

| Consolation | ||

| Positive perspective | ||

| Vicarious empowerment | Bonding | |

| Trust | ||

| Changes in perspective | ||

| Determination | Sense of control | Autonomy |

| Anticipation | ||

| Motivation | Sense of fulfillment | Competency |

| Achievement | ||

| Containment | Grounding | Mood regulation |

| Sedation | ||

| Externalization | Emotional resolution | |

| Ventilation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, Y.; Chong, H.J. Online Song Intervention Program to Cope with Work Distress of Remote Dispatched Workers: Music for an Adaptive Environment in the Hyperconnected Era. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070869

Wei Y, Chong HJ. Online Song Intervention Program to Cope with Work Distress of Remote Dispatched Workers: Music for an Adaptive Environment in the Hyperconnected Era. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):869. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070869

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Yaming, and Hyun Ju Chong. 2025. "Online Song Intervention Program to Cope with Work Distress of Remote Dispatched Workers: Music for an Adaptive Environment in the Hyperconnected Era" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070869

APA StyleWei, Y., & Chong, H. J. (2025). Online Song Intervention Program to Cope with Work Distress of Remote Dispatched Workers: Music for an Adaptive Environment in the Hyperconnected Era. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070869