The Associations Between Parental Playfulness, Parenting Styles, the Coparenting Relationship and Child Playfulness

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Children’s Playfulness and Parental Playfulness

1.2. Parental Playfulness and Other Parenting Behaviors

1.3. Parental Playfulness and Coparenting Relationships

1.4. Parental Playfulness and Role Overload

1.5. Paternal and Maternal Playfulness

1.6. The Present Study

1.6.1. Objective 1: Parental Playfulness and Children’s Playfulness

1.6.2. Objective 2: Parental Playfulness and Other Parenting Behaviors

1.6.3. Objective 3: Parental Playfulness and Coparenting

1.6.4. Objective 4: Parental Playfulness and Role Overload

1.6.5. Objective 5: Differences in Playfulness Between Mothers and Fathers

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Parental Playfulness

2.3.2. Parenting Behaviors

2.3.3. Coparenting Relationship

2.3.4. Parental Role and Involvement

2.3.5. Children’s Playfulness

2.3.6. Sociodemographic Information

2.4. Plan of Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Primary Analyses

3.2.1. Objective 1: Children’s Playfulness

3.2.2. Objective 2: Parental Behaviors

3.2.3. Objective 3: Coparenting Relationship

3.2.4. Objective 4: Role Overload

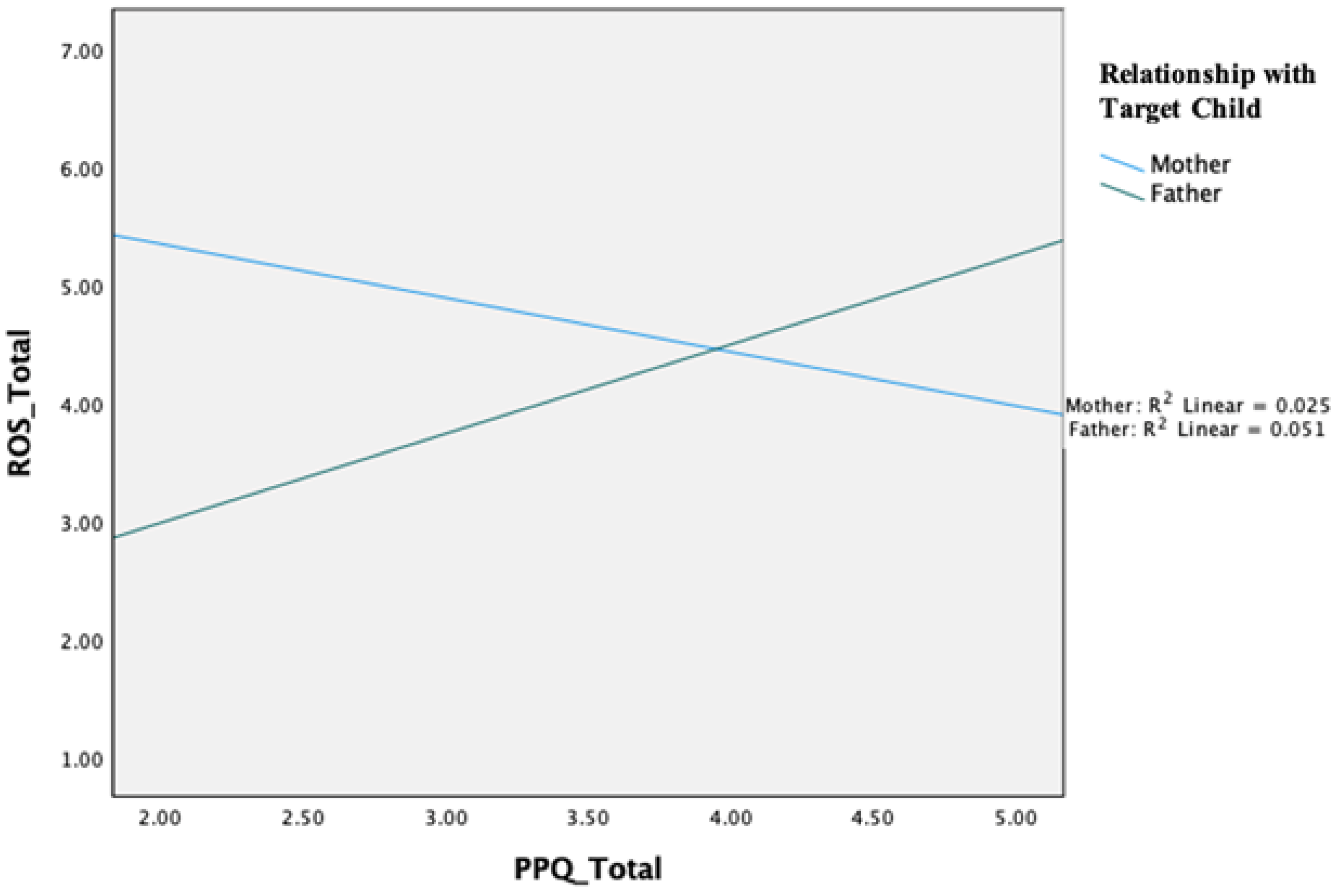

3.2.5. Objective 5: Mother–Father Differences

4. Discussion

4.1. Objective 1: Children’s Playfulness

4.2. Objective 2: Parental Behaviors

4.3. Objective 3: Coparenting Relationship

4.4. Objective 4: Role Overload

4.5. Objective 5: Mother–Father Differences

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahn, J. S., Ratelle, C. F., Plamondon, A., Duchesne, S., & Guay, F. (2022). Testing reciprocal associations between parenting and youth’s motivational resources of career decision-making agency during the postsecondary transition. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(12), 2396–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahnert, L., Teufl, L., Ruiz, N., Piskernik, B., Supper, B., Remiorz, S., Gesing, A., & Nowacki, K. (2017). Father–child play during the preschool years and child internalizing behaviors: Between robustness and vulnerability. Infant Mental Health Journal, 38(6), 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amodia-Bidakowska, A., Laverty, C., & Ramchandani, P. G. (2020). Father-child play: A systematic review of its frequency, characteristics and potential impact on children’s development. Developmental Review, 57, 100924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S., Qiu, W., & Wheeler, S. J. (2017). The quality of father–child rough-and-tumble play and toddlers’ aggressive behavior in China. Infant Mental Health Journal, 38(6), 726–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, K. S., & Wong, N. C. H. (2002). Antecedents and consequences of adult play in romantic relationships. Personal Relationships, 9(3), 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytuglu, A., & Brown, G. L. (2022). Pleasure in parenting as a mediator between fathers’ attachment representations and paternal sensitivity. Journal of Family Psychology, 36(3), 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1971). Social learning theory. General Learning Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, L. A. (1991a). Characterizing playfulness: Correlates with individual attributes and personality traits. Play & Culture, 4(4), 371–393. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, L. A. (1991b). The playful child: Measurement of a disposition to play. Play & Culture, 4(1), 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, L. A. (2007). The nature of playfulness in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(4), 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, L. A. (1992). Forms and functions of intimate play in personal relationships. Human Communication Research, 18(3), 336–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau, J.-F., Bandk, K., Deneault, A.-A., Turgeon, J., Seal, H., & Brosseau-Liard, P. (2023). The PPSQ: Assessing parental, child, and partner’s playfulness in the preschool and early school years. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1274160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bureau, J.-F., Yurkowski, K., Schmiedel, S., Martin, J., Moss, E., & Pallanca, D. (2014). Making children laugh: Parent-child dyadic synchrony and preschool attachment. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35(5), 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, N. J., Fitzgerald, H. E., Bradley, R. H., & Roggman, L. (2014). The ecology of father-child relationships: An expanded model. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 6(4), 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, N. J., & Roggman, L. (2017). Father play: Is it special? Infant Mental Health Journal, 38(6), 706–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, N. J., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Bradley, R. H., Hofferth, S., & Lamb, M. E. (2000). Fatherhood in the twenty-first century. Child Development, 71(1), 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, A. (2017). Social desirability bias in self-reported well-being measures: Evidence from an online survey. Universitas Psychologica, 16(2), 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.-J., Qian, X., & Yarnal, C. (2013). Using playfulness to cope with psychological stress: Taking into account both positive and negative emotions. International Journal of Play, 2(3), 273–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, J. E., Deneault, A., Devereux, C., Eirich, R., Fearon, R. M. P., & Madigan, S. (2022). Parental sensitivity and child behavioral problems: A meta-analytic review. Child Development, 93(5), 1231–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deneault, A., Cabrera, N. J., & Bureau, J. (2022). A meta-analysis on observed paternal and maternal sensitivity. Child Development, 93(6), 1631–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrant, J. E. (2020). Positive discipline in everyday parenting (PDEP). In E. T. Gershoff, & S. J. Lee (Eds.), Ending the physical punishment of children: A guide for clinicians and practitioners (pp. 89–97). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erel, O., & Burman, B. (1995). Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 118(1), 108–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, J., Day, R., Lamb, M. E., & Cabrera, N. J. (2014). Should researchers conceptualize differently the dimensions of parenting for fathers and mothers? Journal of Family Theory & Review, 6(4), 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, M. E., Brown, L. D., & Kan, M. L. (2012). A multi-domain self-report measure of coparenting. Parenting, 12(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorini, M., & Keane, M. P. (2014). How the allocation of children’s time affects cognitive and noncognitive development. Journal of Labor Economics, 32(4), 787–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glynn, M. A., & Webster, J. (1992). The adult playfulness scale: An initial assessment. Psychological Reports, 71(1), 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, N. L., McFarland, L., Jacobvitz, D., & Boyd-Soisson, E. (2010). Fathers’ frightening behaviours and sensitivity with infants: Relations with fathers’ attachment representations, father–infant attachment, and children’s later outcomes. Early Child Development and Care, 180(1–2), 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, K. T., Marvin, R. S., Cooper, G., & Power, B. (2006). Changing toddlers’ and preschoolers’ attachment classifications: The circle of security intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(6), 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsin, A., & Felfe, C. (2014). When does time matter? Maternal employment, children’s time with parents, and child development. Demography, 51(5), 1867–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A., Halliburton, A., & Humphrey, J. (2013). Child–mother and child–father play interaction patterns with preschoolers. Early Child Development and Care, 183(3–4), 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J. D., Cassidy, J., & Shaver, P. R. (2015). Parents’ self-reported attachment styles: A review of links with parenting behaviors, emotions, and cognitions. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 19(1), 44–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrell, F. (1994). A typical interaction behaviour between fathers and toddlers: Teasing. Early Development and Parenting, 3(2), 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levavi, K., Menashe-Grinberg, A., Barak-Levy, Y., & Atzaba-Poria, N. (2020). The role of parental playfulness as a moderator reducing child behavioural problems among children with intellectual disability in Israel. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 107, 103793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, S., Prime, H., Graham, S. A., Rodrigues, M., Anderson, N., Khoury, J., & Jenkins, J. M. (2019). Parenting behavior and child language: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 144(4), e20183556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnuson, C. D., & Barnett, L. A. (2013). The playful advantage: How playfulness enhances coping with stress. Leisure Sciences, 35(2), 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdandžić, M., De Vente, W., & Bögels, S. M. (2016). Challenging parenting behavior from infancy to toddlerhood: Etiology, measurement, and differences between fathers and mothers. Infancy, 21(4), 423–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdandžić, M., Lazarus, R. S., Oort, F. J., Van Der Sluis, C., Dodd, H. F., Morris, T. M., De Vente, W., Byrow, Y., Hudson, J. L., & Bögels, S. M. (2018). The structure of challenging parenting behavior and associations with anxiety in Dutch and Australian children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(2), 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, B. A., Brown, G. L., Bost, K. K., Shin, N., Vaughn, B., & Korth, B. (2005). Paternal identity, maternal gatekeeping, and father involvement. Family Relations, 54(3), 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menashe-Grinberg, A., & Atzaba-Poria, N. (2017). Mother–child and father–child play interaction: The importance of parental playfulness as a moderator of the links between parental behavior and child negativity. Infant Mental Health Journal, 38(6), 772–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofson, E. L., & Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J. (2022). Same behaviors, different outcomes: Mothers’ and fathers’ observed challenging behaviors measured using a new coding system relate differentially to children’s social-emotional development. Children, 9(5), 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakaluk, C. R., & Price, J. (2020). Are mothers and fathers interchangeable caregivers? Marriage & Family Review, 56(8), 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette, D. (2004). Theorizing the father-child relationship: Mechanisms and developmental outcomes. Human Development, 47(4), 193–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prime, H., Wade, M., & Browne, D. T. (2020). Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 75(5), 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proyer, R. T. (2013). The well-being of playful adults: Adult playfulness, subjective well-being, physical well-being, and the pursuit of enjoyable activities. European Journal of Humour Research, 1(1), 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proyer, R. T. (2014a). Perceived functions of playfulness in adults: Does it mobilize you at work, rest, and when being with others? European Review of Applied Psychology, 64(5), 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proyer, R. T. (2014b). To love and play: Testing the association of adult playfulness with the relationship personality and relationship satisfaction. Current Psychology, 33(4), 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M., Sokolovic, N., Madigan, S., Luo, Y., Silva, V., Misra, S., & Jenkins, J. (2021). Paternal sensitivity and children’s cognitive and socioemotional outcomes: A meta-analytic review. Child Development, 92(2), 554–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C. S., Impara, J. C., Frary, R. B., Harris, T., Meeks, A., Semanic-Lauth, S., & Reynolds, M. (1998). Measuring playfulness: Development of the child behavior inventory of playfulness. In M. Duncan, G. Chick, & A. Aycock (Eds.), Play and cultural studies (Vol. 4, pp. 121–135). Ablex Publishing Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Román-Oyola, R., Reynolds, S., Soto-Feliciano, I., Cabrera-Mercader, L., & Vega-Santana, J. (2017). Child’s sensory profile and adult playfulness as predictors of parental self-efficacy. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(2), 7102220010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, I., Sayer, M., & Goodale, A. (1999). The relationship between playfulness and coping in preschool children: A pilot study. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 53(2), 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmiedel, S. (2021). Comment faire rire les enfants d’âge préscolaire: Développement d’un système de codification et liens avec l’attachement enfant-père et enfant-mère [Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Psychology, University of Ottawa]. [Google Scholar]

- Shorer, M., & Leibovich, L. (2022). Young children’s emotional stress reactions during the COVID-19 outbreak and their associations with parental emotion regulation and parental playfulness. Early Child Development and Care, 192(6), 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorer, M., Swissa, O., Levavi, P., & Swissa, A. (2021). Parental playfulness and children’s emotional regulation: The mediating role of parents’ emotional regulation and the parent–child relationship. Early Child Development and Care, 191(2), 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stgeorge, J., & Freeman, E. (2017). Measurement of father–child rough-and-tumble play and its relations to child behavior. Infant Mental Health Journal, 38(6), 709–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teufl, L., & Ahnert, L. (2022). Parent–child play and parent–child relationship: Are fathers special? Journal of Family Psychology, 36(3), 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiagarajan, P., Chakrabarty, S., & Taylor, R. D. (2006). A confirmatory factor analysis of reilly’s role overload scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevlas, E., Grammatikopoulos, V., Tsigilis, N., & Zachopoulou, E. (2003). Evaluating playfulness: Construct validity of the children’s playfulness scale. Early Childhood Education Journal, 31(1), 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ijzendoorn, M. H., Vereijken, C. M. J. L., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Riksen-Walraven, J. M. A. (2004). Assessing attachment security with the attachment Q sort: Meta-analytic evidence for the validity of the observer AQS. Child Development, 75(4), 1188–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Salisch, M. (2001). Children’s emotional development: Challenges in their relationships to parents, peers, and friends. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 25(4), 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A., Tian, Y., Chen, S., & Cui, L. (2024). Do playful parents raise playful children? A mixed methods study to explore the impact of parental playfulness on children’s playfulness. Early Education and Development, 35(2), 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youell, B. (2008). The importance of play and playfulness. European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling, 10(2), 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X. D., Leung, C.-L., & Hiranandani, N. A. (2016). Adult playfulness, humor styles, and subjective happiness. Psychological Reports, 119(3), 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zick, C. D., Bryant, W. K., & Österbacka, E. (2001). Mothers’ employment, parental involvement, and the implications for intermediate child outcomes. Social Science Research, 30(1), 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubrick, S. R., Lucas, N., Westrupp, E. M., & Nicholson, J. M. (2014). Parenting measures in the longitudinal study of Australian children: Construct validity and measurement quality, waves 1 to 4. Department of Social Sciences. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | CPS Phys Spontaneity a,d | CPS Manifest Joy a,c,f | CPS Sense of Humor a,e | CPS Soc Spontaneity d,e | CPS Cog Spontaneity a,d,e | CBI a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPQ a | Correlation | 0.04 | 0.29 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.12 | 0.37 *** | 0.36 *** |

| Significance | 0.46 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.04 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| APS a,b | Correlation | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.15 ** | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.11 |

| Significance | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.009 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.07 |

| Variable | CPBQ | PBQ Warmth | PBQ Hostility a | PBQ Anger e | PBQ Consistency | PBQ Parental Separation Anxiety c,d | PBQ Inductive Reasoning b,c | PBQ Efficacy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPQ a | Correlation | 0.15 ** | 0.21 *** | −0.19 *** | −0.21 *** | 0.09 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.18 *** |

| Significance | 0.006 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.57 | 0.85 | 0.001 | |

| APS a,b | Correlation | 0.16 ** | 0.08 | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.06 | −0.01 | 0.06 |

| Significance | 0.005 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.32 | 0.82 | 0.27 |

| Variable | CRS Cop. Agreement | CRS Cop. Closeness | CRS Exp. Conflict a | CRS Cop. Support c | CRS Cop. Undermining | CRS Partner Parenting c | CRS Coparenting Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPQ a | Correlation | 0.09 | −0.07 | −0.12 | 0.11 | −0.23 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.09 |

| Significance | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.14 | |

| APS a,b | Correlation | 0.05 | −0.05 | −0.12 | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| Significance | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.04 | 0.35 | 0.43 | 0.38 | 0.61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seal, H.; Bureau, J.-F.; Deneault, A.-A. The Associations Between Parental Playfulness, Parenting Styles, the Coparenting Relationship and Child Playfulness. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 867. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070867

Seal H, Bureau J-F, Deneault A-A. The Associations Between Parental Playfulness, Parenting Styles, the Coparenting Relationship and Child Playfulness. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):867. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070867

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeal, Harshita, Jean-François Bureau, and Audrey-Ann Deneault. 2025. "The Associations Between Parental Playfulness, Parenting Styles, the Coparenting Relationship and Child Playfulness" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 867. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070867

APA StyleSeal, H., Bureau, J.-F., & Deneault, A.-A. (2025). The Associations Between Parental Playfulness, Parenting Styles, the Coparenting Relationship and Child Playfulness. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 867. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070867