The Impact of Informal Digital Learning of English (IDLE) on EFL Learners’ Engagement: Mediating Roles of Flow, Online Self-Efficacy, and Behavioral Intention

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. IDLE

2.2. Flow, Online Self-Efficacy, and Behavioral Intention

2.3. Engagement, Flow, Online Self-Efficacy, and Behavioral Intention

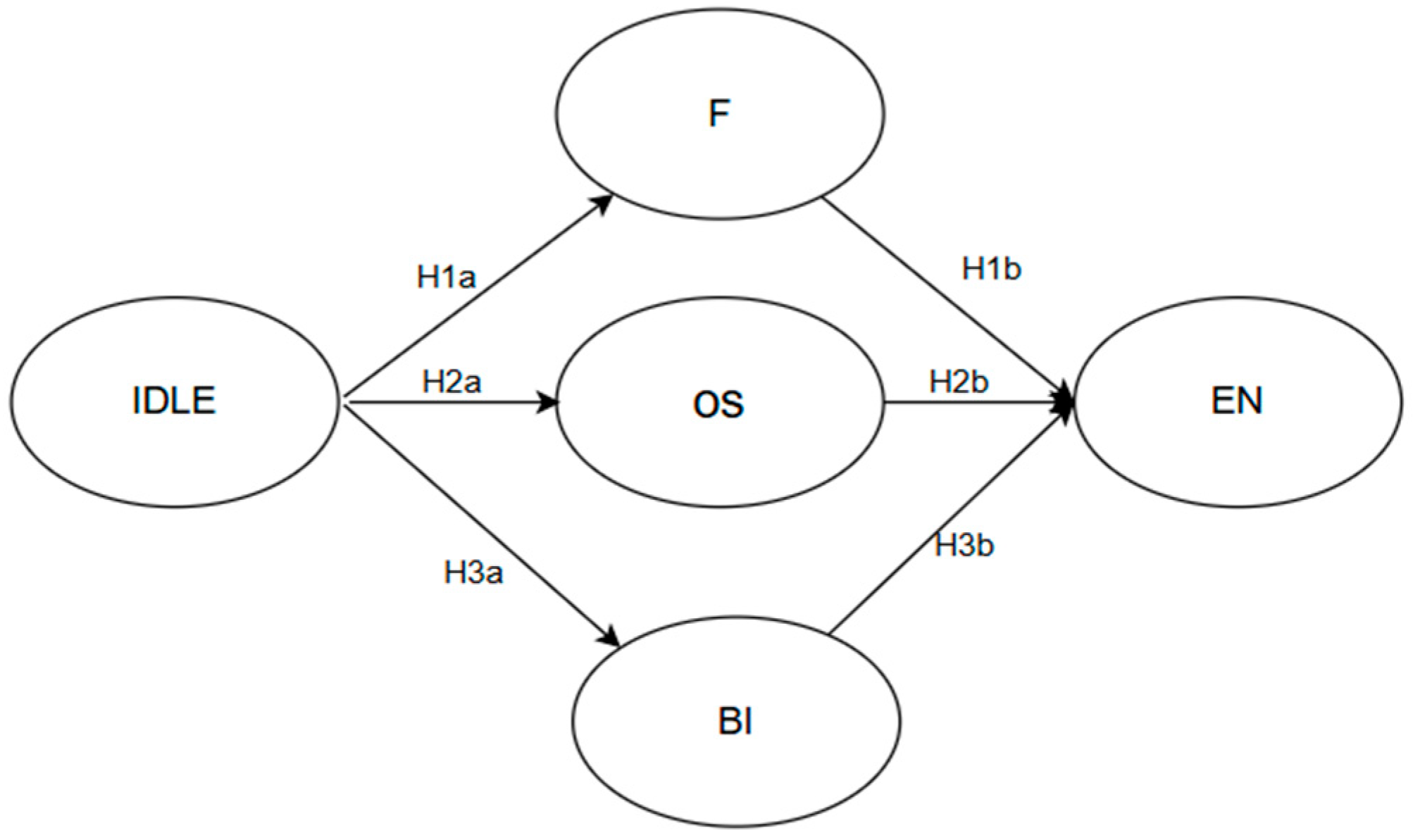

2.4. The Hypothesized Structural Model

2.5. Research Questions

- RQ1: Does flow mediate the relationship between IDLE and EFL learners’ engagement, and what specific mediating role does it play?

- RQ2: Does online self-efficacy mediate the relationship between IDLE and EFL learners’ engagement, and what specific mediating role does it play?

- RQ3: Does behavioral intention mediate the relationship between IDLE and EFL learners’ engagement, and what specific mediating role does it play?

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Research Instrument

3.2.1. Informal Digital Learning of English (IDLE)

3.2.2. Engagement

3.2.3. Flow

3.2.4. Online Self-Efficacy

3.2.5. Behavioral Intention

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Reliability/Validity Checks

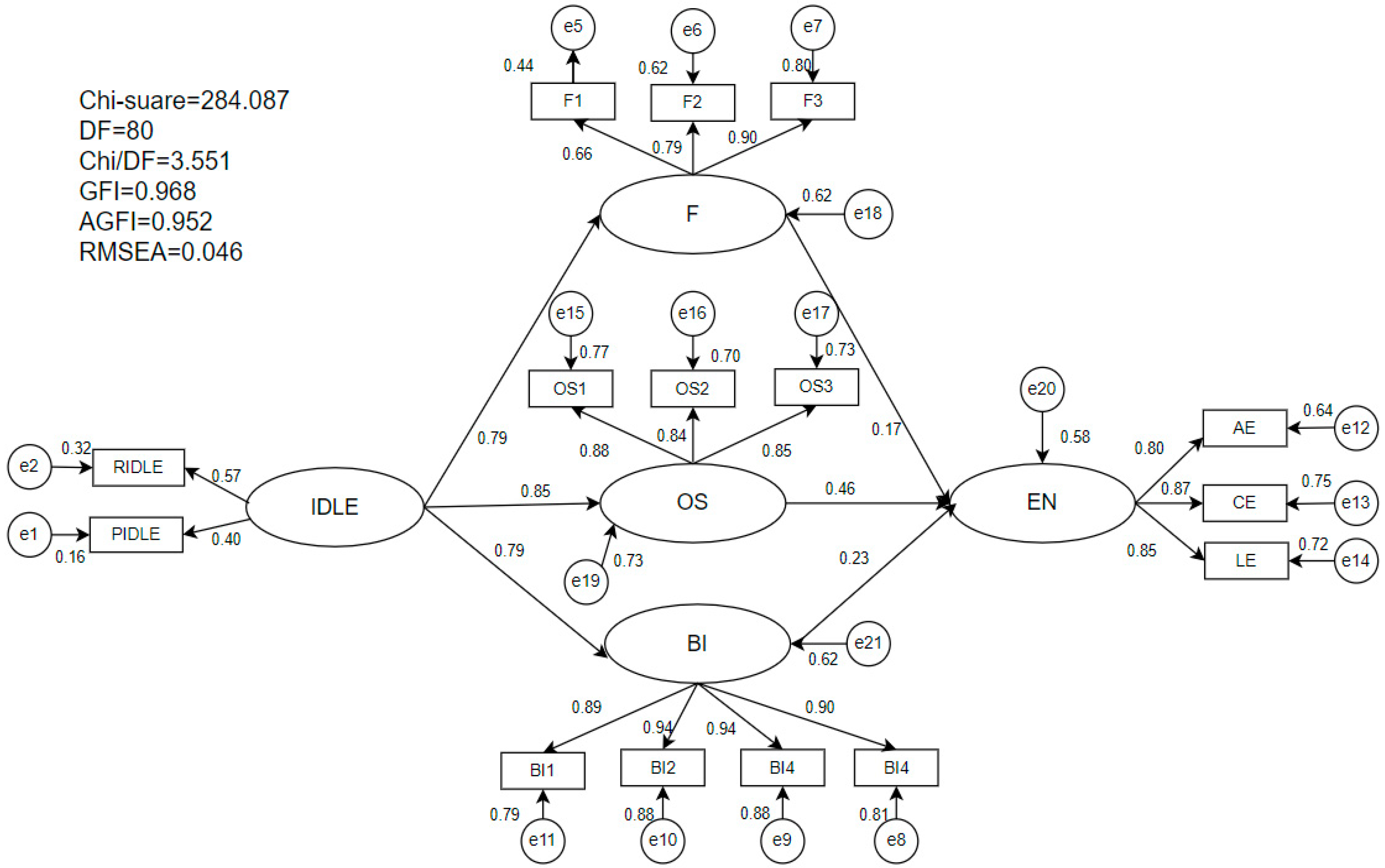

4.3. The Structural Model and Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. The Mediating Role of Flow

5.2. The Mediating Role of Online Self-Efficacy

5.3. The Mediating Role of Behavioral Intention

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action-control: From cognition to behavior (pp. 11–39). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algharabat, R. S., & Rana, N. P. (2020). Social Commerce in emerging markets and its impact on online community engagement. Information Systems Frontiers, 23, 1499–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, S. H., & Babu, E. (2025). The mediating role of satisfaction in the relationship between perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and students’ behavioral intention to use ChatGPT. Scientific Reports, 15, 7169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arndt, H. (2023). Construction and validation of a questionnaire to study engagement in informal second language learning. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 45(5), 1456–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. Self-Efficacy Beliefs in Adolescence, 5, 307–337. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, P. (2011). Language learning and teaching beyond the classroom: An introduction to the field. In P. Benson, & H. Reinders (Eds.), Beyond the language classroom (pp. 7–16). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Budu, K. W. A., Mu, Y. P., & Mireku, K. K. (2018). Investigating the effect of behavioral intention on e-learning systems usage: Empirical study on tertiary education institutions in Ghana. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 9(3), 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil, I., Catalan, S., & Martınez, E. (2019). The influence of flow on learning outcomes: An empirical study on the use of clickers. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(1), 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q., Lin, Y., & Yu, Z. (2023). Factors influencing learner attitudes towards ChatGPT-assisted language learning in higher education. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 40(22), 7112–7126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. S., Liu, E. Z. F., Sung, H. Y., Lin, C. H., Chen, N. S., & Cheng, S. S. (2014). Effects of online college student’s internet self-efficacy on learning motivation and performance. Innovative Education and Teaching International, 51, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y. J., Chen, C. H., Huang, W. T., & Huang, W. S. (2011, 11–15 July). Investigating students’ perceived satisfaction, behavioral intention, and effectiveness of English learning using augmented reality. 2011 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo, Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, M. H., Shen, D., & Lafey, J. (2010). The role of metacognitive self-regulation (MSR) on social presence and sense of community in online learning environments. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 21(3), 297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., & Wylie, C. (2012). Handbook of research on student engagement. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y., & Meng, Y. (2023). The relationship between self-efficacy, foreign language pleasure and English proficiency from the perspective of positive psychology. Foreign Languages Research, 40(1), 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Derakhshan, A., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., & Ortega-Martín, J. L. (2023). Towards innovative research approaches to investigating the role of emotional variables in promoting language teachers’ and learners’ mental health. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 25(7), 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, M. D. (2012). Creating effective student engagement in online courses: What do students find engaging? Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 10(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Egbert, J. (2003). A study of flow theory in the foreign language classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 87(4), 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C. Y., & Wang, J. (2023). Undergraduates’ behavioral intention to use indigenous Chinese Web 2.0 tools in informal English learning: Combining language learning motivation with technology acceptance model. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(330), 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, K. A., Gamage, A., & Dehideniya, S. C. (2022). Online and hybrid teaching and learning: Enhance effective student engagement and experience. Education Sciences, 12(10), 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y., Wang, X., & Reynolds, B. (2025). The mediating roles of resilience and flow in linking basic psychological needs to tertiary efl learners’ engagement in the informal digital learning of English: A mixed-methods study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J., Shernoff, D. J., Rowe, E., Coller, B., Asbell-Clarke, J., & Edwards, T. (2016). Challenging games help students learn: An empirical study on engagement, flow and immersion in game—Based learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T., Zhu, C., & Questier, F. (2018). Predicting digital informal learning: An empirical study among Chinese university students. Asia Pacific Education Review, 19, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J. C., Hwang, M. Y., Tai, K. H., & Lin, P. H. (2017). Intrinsic motivation of Chinese learning in predicting online learning self-efficacy and flow experience relevant to students’ learning progress. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 30(6), 552–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. C., Huang, L. S., Chou, Y. J., & Teng, C. I. (2017). Influence of temperament and character on online gamer loyalty: Perspectives from personality and flow theories. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, L. K. (2016). Exploring flow experiences in cooperative digital gaming contexts. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (5th ed.). Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kuan, F. C. Y., & Lee, S. W. (2022). Effects of self-efficacy and learning environment on Hong Kong Undergraduate students’ academic performance in online learning. Public Administration and Policy, 25(3), 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C., Zhu, W., & Gong, G. (2015). Understanding the quality of out-of-class English learning. TESOL Quarterly, 49(2), 278–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. S. (2019). Quantity and diversity of informal digital learning of English. Language Learning & Technology, 23(1), 114–126. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. S. (2020). Informal digital learning of English and strategic competence for cross-cultural communication: Perception of varieties of English as a mediator. ReCALL, 32(1), 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. S. (2022). Informal digital learning of English: Research to practice. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. S., & Drajati, N. A. (2019a). Affective variables and informal digital learning of English: Keys to willingness to communicate in a second language. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 35(5), 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. S., & Drajati, N. A. (2019b). English as an international language beyond the ELT classroom. ELT Journal, 73(4), 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. S., & Lee, K. (2021). The role of informal digital learning of English and L2 motivational self system in foreign language enjoyment. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(1), 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. S., & Sylvén, L. K. (2021). The role of informal digital learning of English in Korean and Swedish EFL learners’ communication behaviour. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(3), 1279–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R., Meng, Z., Tian, M., Zhang, Z., & Xiao, W. (2021). Modelling Chinese EFL learners’ flow experiences in digital game—based vocabulary learning: The roles of learner and contextual factors. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 34(4), 483–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. L., Darvin, R., & Ma, C. (2024a). Unpacking the role of motivation and enjoyment in AI-mediated informal digital learning of English (AI-IDLE): A mixed-method investigation in the Chinese context. Computers in Human Behavior, 160, 108362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. L., & Wang, Y. (2024). Modeling EFL teachers’ intention to integrate informal digital learning of English (IDLE) into the classroom using the theory of planned behavior. System, 120, 103193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. L., Zhao, X., & Yang, B. (2024b). The predictive effects of motivation, enjoyment, and self-efficacy on informal digital learning of English. System, 126, 103504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., & Song, X. (2021). Exploring ‘flow’ in young Chinese EFL learners’ online English learning activities. System, 96(1), 102425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyrigkou, C. (2019). Not to be overlooked: Agency in informal language contact. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 13(3), 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M., Chen, Y., Du, X., & Seddon, J. M. (2023). Deep ensemble learning for automated non-advanced AMD classification using optimized retinal layer segmentation and SD-OCT scans. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 154, 106512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özhan, Ş. Ç., & Kocadere, S. A. (2020). The effects of flow, emotional engagement, and motivation on success in a gamified online learning environment. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 57(8), 2006–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W. (2017). Research on model of student engagement in online learning. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 13, 2869–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proietti Ergün, A. L., & Ersöz Demirdağ, H. (2023). The predictive effect of subjective well-being and stress on foreign language enjoyment: The mediating effect of positive language education. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1007534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, A. (2021). Using students’ experience to derive effectiveness of COVID-19-lockdown-induced emergency online learning at undergraduate level: Evidence from Assam, India. Higher Education Futures, 8, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Pilco, S. Z., Yang, Y., & Zhang, Z. (2022). Student engagement in online learning in Latin American higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53, 593–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santosa, P. (2015). Student engagement with online tutorial: A perspective on flow theory. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 10(1), 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sockett, G. (2014). The online informal learning of English. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Sockett, G., & Toffoli, D. (2012). Beyond learner autonomy: A dynamic systems view of the informal learning of English in virtual online communities. ReCALL, 24(2), 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyoof, A., Reynolds, B. L., Vazquez-Calvo, B., & McLay, K. (2023). Informal digital learning of English (IDLE): A scoping review of what has been done and a look towards what is to come. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 36(4), 608–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y., Zheng, C. P., Liang, J. C., & Tsai, C. C. (2018). Examining the relationship between English language learners’ online self—Regulation and their self—Efficacy. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 34(3), 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J. C.-Y., & Rueda, R. (2012). Situational interest, computer self-efficacy and self-regulation: Their impact on student engagement in distance education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(2), 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L., Zhang, C., & Cui, Y. (2024). A multigroup SEM analysis of mediating role of enjoyment, anxiety, and boredom in the relationships between L2 motivational self-system, L2 proficiency, and intercultural communication competence. Language Teaching Research, 29(3), 13621688241265211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. T., Fredricks, J. A., Ye, F., Hofkens, T. L., & Lin, J. S. (2016). The math and science engagement scales: Development, validation, and psychometric properties. Learning and Instruction, 43, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R. L. (2023). The relationship between online learning self-efficacy, informal digital learning of English, and student engagement in online classes: The mediating role of social presence. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1266009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T., & Li, F. (2021, 17–21 August). The influence of online learning self-efficacy on learning engagement among middle school students: The mediating role of learning motivation [Contribution to conference]. 2021 16th International Conference on Computer Science & Education (ICCSE) (pp. 61–65), Lancaster, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S., Zhu, H., & Zhou, Y. (2022). Impact of Teenager EFL Learners’ Psychological Needs on Learning Engagement and Behavioral Intention in Synchronous Online English Courses. Sustainability, 14(17), 10468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | M | SD | Kurtosis | Skewness | Factor Loading | α (>0.7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDLE | RIDLE | 3.239 | 0.530 | 0.472 | −0.207 | 0.914 | 0.824 |

| PIDLE | 2.139 | 0.603 | 0.173 | 0.637 | 0.623 | ||

| EN | AE | 3.851 | 0.462 | 0.711 | −0.25 | 0.804 | 0.918 |

| CE | 3.579 | 0.424 | 0.47 | 0.019 | 0.866 | ||

| LE | 3.526 | 0.427 | 0.697 | −0.093 | 0.848 | ||

| BI | BI1 | 3.660 | 0.600 | 0.647 | −0.397 | 0.887 | 0.864 |

| BI2 | 3.700 | 0.570 | 0.701 | −0.452 | 0.936 | ||

| BI3 | 3.690 | 0.563 | 0.674 | −0.397 | 0.941 | ||

| BI4 | 3.690 | 0.586 | 0.685 | −0.402 | 0.902 | ||

| F | F1 | 3.040 | 0.634 | 0.493 | 0.067 | 0.662 | 0.954 |

| F2 | 3.150 | 0.600 | 0.421 | 0.085 | 0.783 | ||

| F3 | 3.330 | 0.538 | 0.405 | 0.157 | 0.901 | ||

| OS | OS1 | 3.500 | 0.522 | 0.102 | 0.049 | 0.832 | 0.910 |

| OS2 | 3.520 | 0.535 | 0.211 | −0.055 | 0.896 | ||

| OS3 | 3.540 | 0.517 | 0.19 | −0.021 | 0.913 |

| AVE (>0.5) | CR (>0.7) | HTMT (<0.9) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDLE | EN | BI | F | OS | ||||

| 1 | IDLE | 0.612 | 0.753 | 0.782 | ||||

| 2 | EN | 0.705 | 0.878 | 0.537 | 0.840 | |||

| 3 | BI | 0.841 | 0.955 | 0.498 | 0.635 | 0.917 | ||

| 4 | F | 0.621 | 0.829 | 0.481 | 0.612 | 0.616 | 0.788 | |

| 5 | OS | 0.776 | 0.912 | 0.479 | 0.691 | 0.640 | 0.649 | 0.881 |

| X2/df | CFI | IFI | TLI | RSMEA | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The measurement model | 3.787 | 0.985 | 0.985 | 0.979 | 0.048 | 0.0289 |

| The structural model | 3.551 | 0.986 | 0.986 | 0.981 | 0.046 | 0.0283 |

| Cutoff values (Kline, 2023) | <5 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | <0.10 | <0.08 |

| Path | β | p | t-Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDLE → F | 0.790 | *** | 11.44 | accepted |

| IDLE → OS | 0.852 | *** | 12.31 | accepted |

| IDLE → BI | 0.786 | *** | 12.11 | accepted |

| OS → EN | 0.455 | *** | 10.99 | accepted |

| BI → EN | 0.227 | *** | 6.50 | accepted |

| F → EN | 0.172 | *** | 4.51 | accepted |

| Mediation Paths | 95% Confidence Interval | p (Two-Tailed Significance) | Indirect Effect | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||

| IDLE → F → EN | 0.065 | 0.211 | 0.000 | 0.136 | accepted |

| IDLE → OS → EN | 0.300 | 0.484 | 0.000 | 0.388 | accepted |

| IDLE → BI → EN | 0.117 | 0.243 | 0.000 | 0.178 | accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, F.; Meng, Y.; Tang, L.; Cui, Y. The Impact of Informal Digital Learning of English (IDLE) on EFL Learners’ Engagement: Mediating Roles of Flow, Online Self-Efficacy, and Behavioral Intention. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 851. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070851

Fang F, Meng Y, Tang L, Cui Y. The Impact of Informal Digital Learning of English (IDLE) on EFL Learners’ Engagement: Mediating Roles of Flow, Online Self-Efficacy, and Behavioral Intention. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):851. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070851

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Fang, Yaru Meng, Lingjie Tang, and Yu Cui. 2025. "The Impact of Informal Digital Learning of English (IDLE) on EFL Learners’ Engagement: Mediating Roles of Flow, Online Self-Efficacy, and Behavioral Intention" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 851. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070851

APA StyleFang, F., Meng, Y., Tang, L., & Cui, Y. (2025). The Impact of Informal Digital Learning of English (IDLE) on EFL Learners’ Engagement: Mediating Roles of Flow, Online Self-Efficacy, and Behavioral Intention. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 851. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070851