Rethinking Post-COVID-19 Behavioral Science: Old Questions, New Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Mapping Design

2.2. Systematic Mapping Questions

2.3. Systematic Mapping of the Search Strategy

2.4. Systematic Mapping of Eligibility Criteria

2.5. Systematic Mapping of Data Extraction

2.6. Systematic Mapping of Quality Assessment

2.7. Systematic Mapping of Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Results

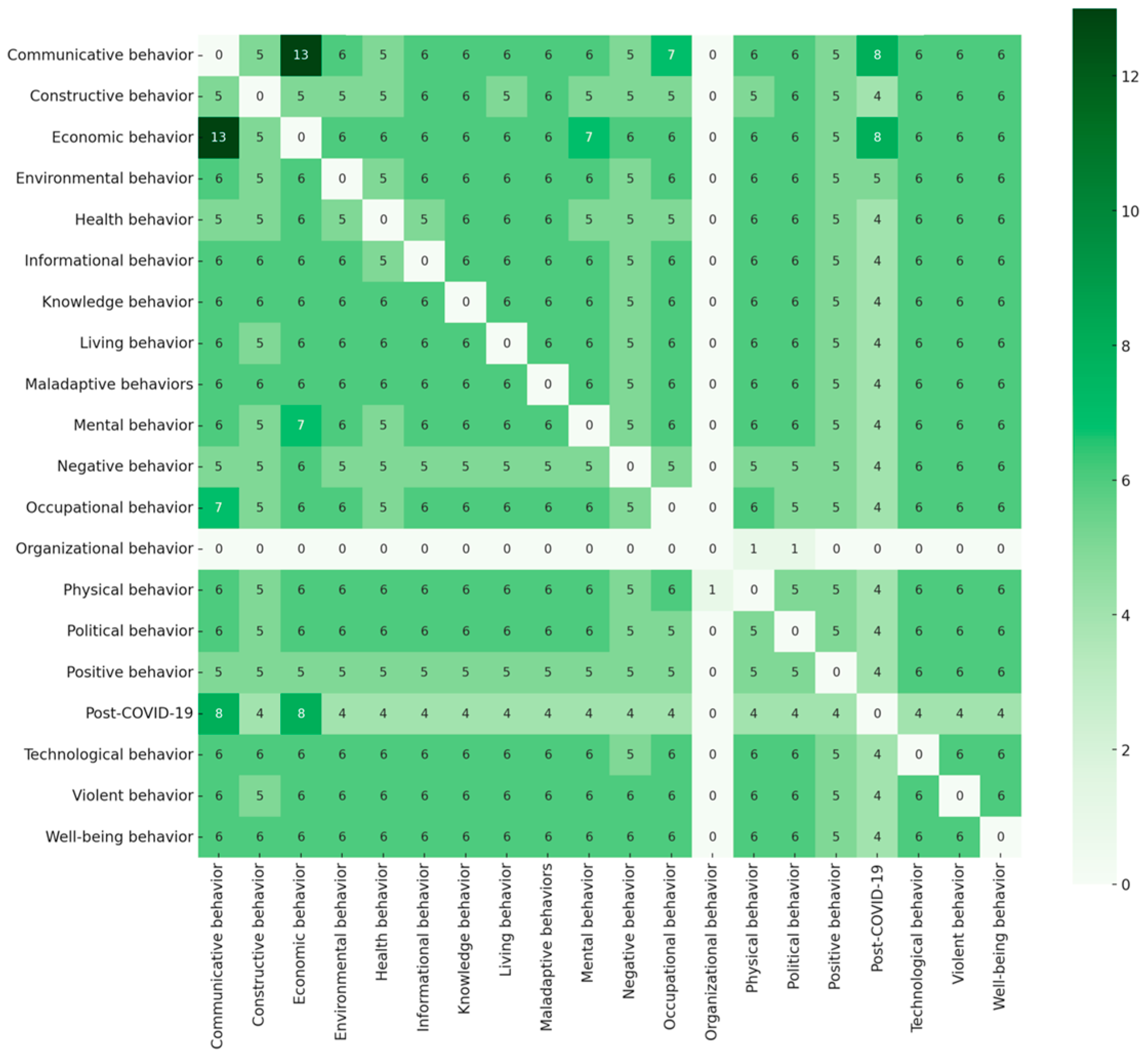

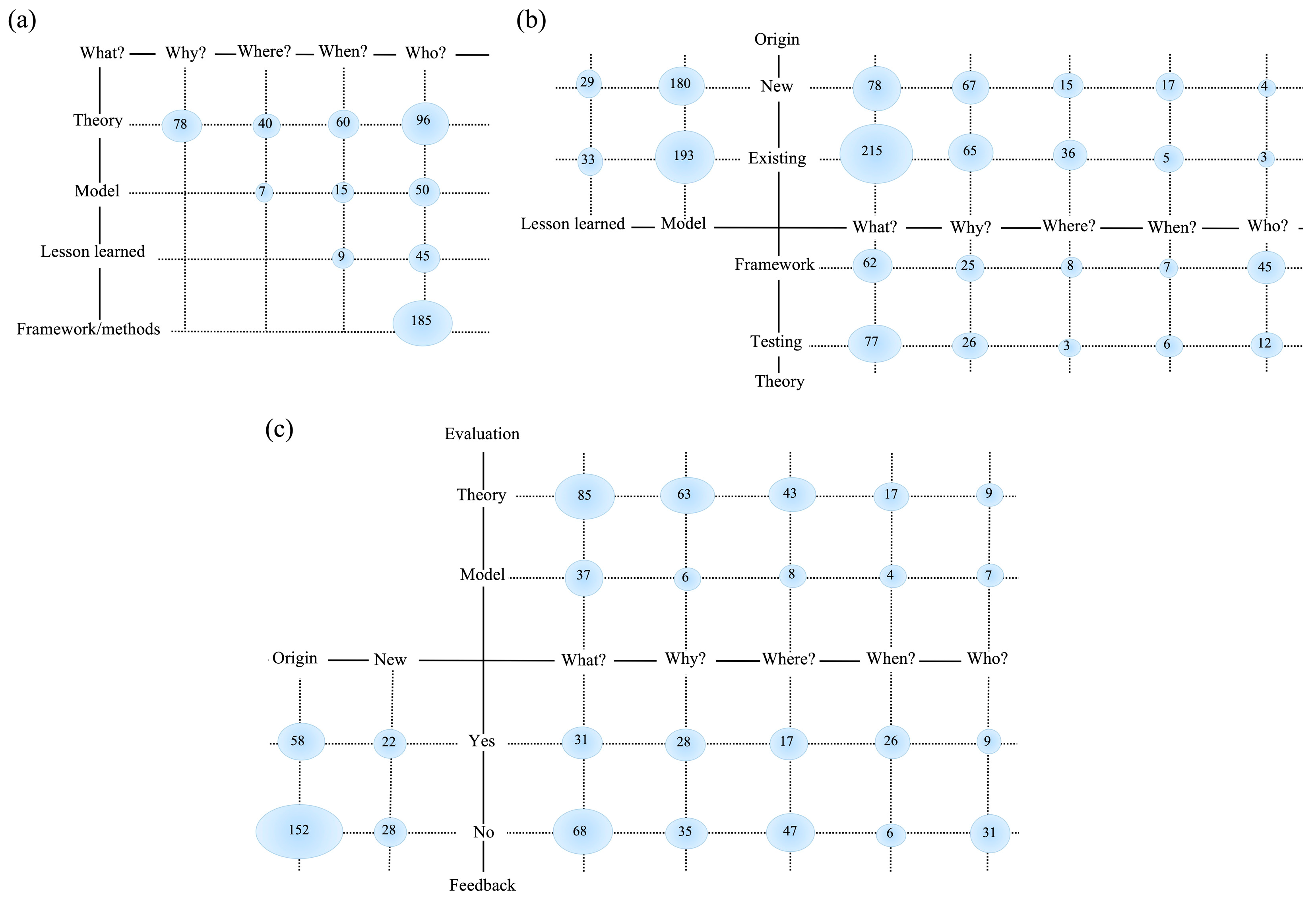

3.2. Principal Mapping Results

3.3. Mapping Results

4. Discussion

4.1. RQ1—What?

4.2. RQ2—Why?

4.3. RQ3—Where?

4.4. RQ4—When?

4.5. RQ5—Who?

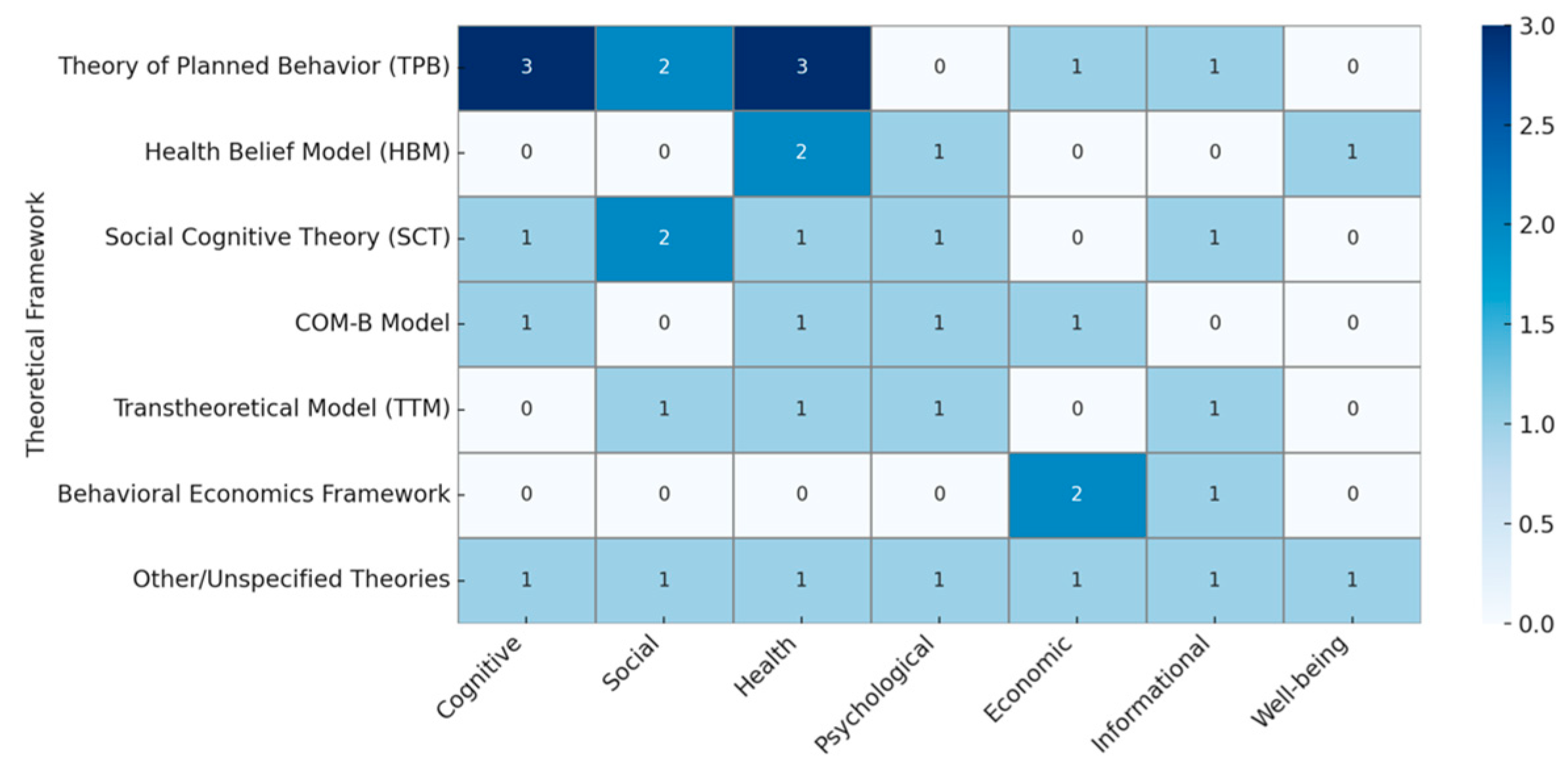

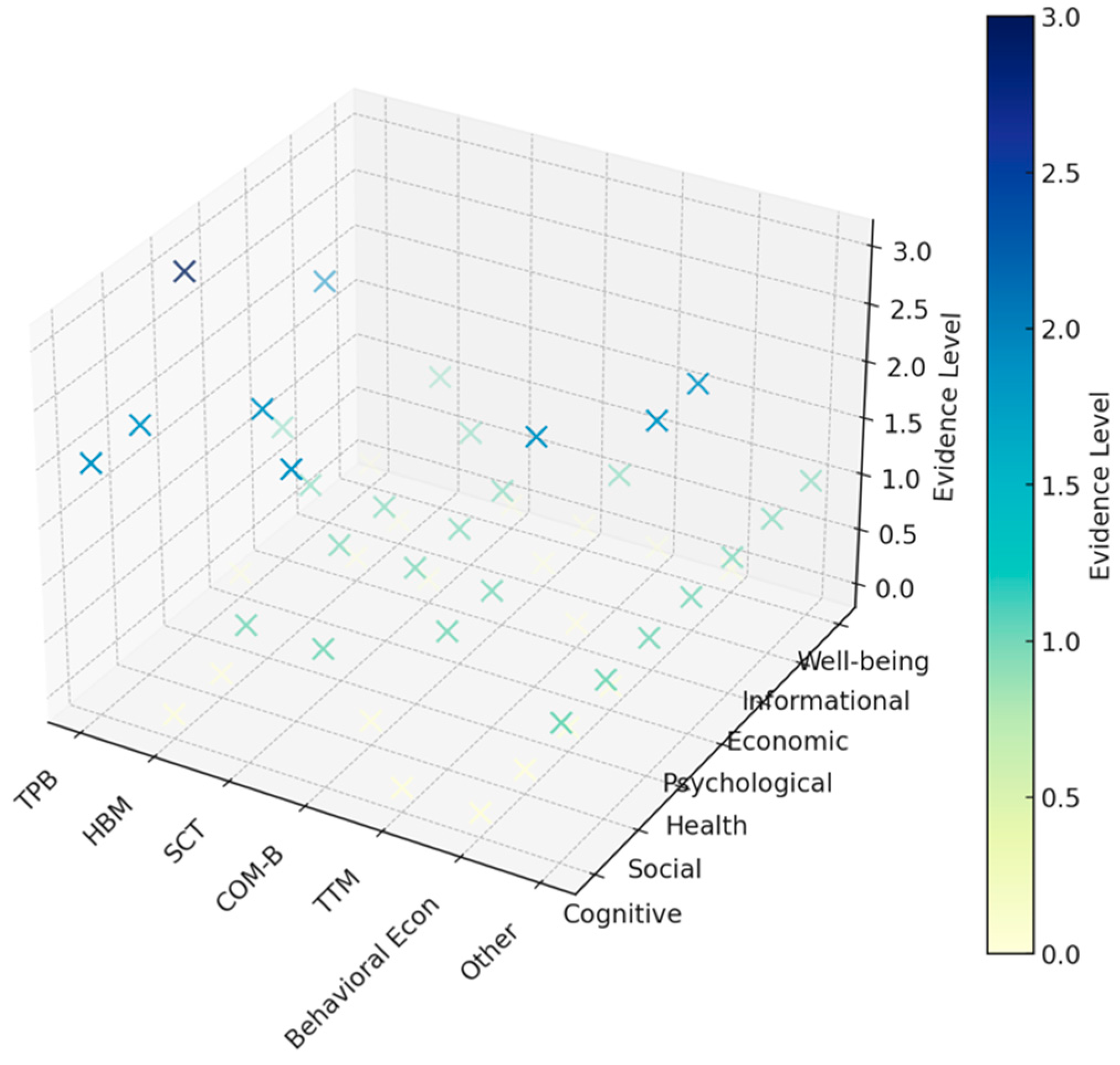

4.6. Theoretical Contributions

4.7. Practical Implications

4.8. Limitations and Future Research

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albarracin, D., & Jung, H. (2021). A research agenda for the post-COVID-19 world: Theory and research in social psychology. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 24(1), 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almaatouq, A., Griffiths, T. L., Suchow, J. W., Whiting, M. E., Evans, J., & Watts, D. J. (2024). Beyond playing 20 questions with nature: Integrative experiment design in the social and behavioral sciences. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 47, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, A. A., & Cabassa, L. J. (2020). Reframing implementation science to address inequities in healthcare delivery. BMC Health Services Research, 20, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavel, J. J. V., Baicker, K., Boggio, P. S., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., Crockett, M. J., Crum, A. J., Douglas, K. M., Druckman, J. N., & Drury, J. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(5), 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger-Tal, O., Greggor, A. L., Macura, B., Adams, C. A., Blumenthal, A., Bouskila, A., Candolin, U., Doran, C., Fernández-Juricic, E., Gotanda, K. M., & Price, C. (2019). Systematic reviews and maps as tools for applying behavioral ecology to management and policy. Behavioral Ecology, 30(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bil, J. S., Buława, B., & Świerzawski, J. (2021). Mental health and the city in the post-COVID-19 era. Sustainability, 13(14), 7533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonizzato, S., Ghiggia, A., Ferraro, F., & Galante, E. (2022). Cognitive, behavioral, and psychological manifestations of COVID-19 in post-acute rehabilitation setting: Preliminary data of an observational study. Neurological Sciences, 43(1), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnjak, M., Ajzen, I., & Schmidt, P. (2020). The theory of planned behavior: Selected recent advances and applications. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 16(3), 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragge, P., Clavisi, O., Turner, T., Tavender, E., Collie, A., & Gruen, R. L. (2011). The global evidence mapping initiative: Scoping research in broad topic areas. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C. J., Tipton, E., & Yeager, D. S. (2021). Behavioural science is unlikely to change the world without a heterogeneity revolution. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(8), 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne-Davis, L. M. T., Turner, R. R., Amatya, S., Ashton, C., Bull, E. R., Chater, A. M., Lewis, L. J. M., Shorter, G. W., Whittaker, E., & Hart, J. K. (2022). Using behavioural science in public health settings during the COVID-19 pandemic: The experience of public health practitioners and behavioural scientists. Acta Psychologica, 224, 103527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabria, M., García-Sánchez, C., Grunden, N., Pons, C., Arroyo, J. A., Gómez-Anson, B., Estévez García, M. D. C., Belvís, R., Morollón, N., Vera Igual, J., & Mur, I. (2022). Post-COVID-19 fatigue: The contribution of cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Journal of Neurology, 269(8), 3990–3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalder, T. (2024). Rehabilitation based on cognitive behavioral model for post–COVID-19 condition. JAMA Network Open, 7(12), e2450756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chater, N., & Loewenstein, G. (2023). The i-frame and the s-frame: How focusing on individual-level solutions has led behavioral public policy astray. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 46, e147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H., Saccardo, S., Han, M. A., Roh, L., Raja, N., Vangala, S., Modi, H., Pandya, S., Sloyan, M., & Croymans, D. M. (2021). Behavioral nudges increase COVID-19 vaccinations. Nature, 597(7876), 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daks, J. S., Peltz, J. S., & Rogge, R. D. (2020). Psychological flexibility and inflexibility as sources of resiliency and risk during a pandemic: Modeling the cascade of COVID-19 stress on family systems with a contextual behavioral science lens. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K., & Bishop, D. B. (2010). The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annual Review of Public Health, 31(1), 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimshaw, J. M., & Russell, I. T. (1993). Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: A systematic review of rigorous evaluations. The Lancet, 342(8883), 1317–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, I., Twardus, O., Varnum, M. E. W., Jayawickreme, E., & McLevey, J. (2022). Expert predictions of societal change: Insights from the world after COVID project. American Psychologist, 77(2), 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M. S., Cheung, M. W.-L., Ajzen, I., & Hamilton, K. (2022). Perceived behavioral control moderating effects in the theory of planned behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 41(2), 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M. S., & Hamilton, K. (2022). Social cognition theories and behavior change in COVID-19: A conceptual review. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 154, 104095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallsworth, M. (2023). A manifesto for applying behavioural science. Nature Human Behaviour, 7(3), 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, S. C., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Wilson, K. G. (2012). Contextual behavioral science: Creating a science more adequate to the challenge of the human condition. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 1(1/2), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krpan, D., Makki, F., Saleh, N., Brink, S. I., & Klauznicer, H. V. (2021). When behavioural science can make a difference in times of COVID-19. Behavioural Public Policy, 5(2), 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. M., & Lee, D. (2021). Opportunities and challenges for contactless healthcare services in the post-COVID-19 era. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 167, 120712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, P., Beck, S., de Brito, M. M., Gawel, E., Groß, M., Haase, A., Lepenies, R., Otto, D., Schiller, J., Strunz, S., & Thrän, D. (2021). Environmental sustainability post-COVID-19: Scrutinizing popular hypotheses from a social science perspective. Sustainability, 13(16), 8679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucarelli, C., Mazzoli, C., & Severini, S. (2020). Applying the theory of planned behavior to examine pro-environmental behavior: The moderating effect of COVID-19 beliefs. Sustainability, 12(24), 10556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiza, T., & Kruger, M. (2021). Ceding to their fears: A taxonomic analysis of the heterogeneity in COVID-19 associated perceived risk and intended travel behaviour. Tourism Recreation Research, 46(2), 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkman, K. L., Gromet, D., Ho, H., Kay, J. S., Lee, T. W., Pandiloski, P., Park, Y., Rai, A., Bazerman, M., Beshears, J., & Bonacorsi, L. (2021). Megastudies improve the impact of applied behavioural science. Nature, 600(7889), 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C. J., Barnett, M. L., Baumann, A. A., Gutner, C. A., & Wiltsey-Stirman, S. (2021). The FRAME-IS: A framework for documenting modifications to implementation strategies in healthcare. Implementation Science, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N. P., Das, S. S., Yadav, S., Khan, W., Afzal, M., Alarifi, A., Alarifi, A., Ansari, M. T., Hasnain, M. S., & Nayak, A. K. (2020). Global impacts of pre-and post-COVID-19 pandemic: Focus on socio-economic consequences. Sensors International, 1, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mladenović, D., Todua, N., & Pavlović-Höck, N. (2023). Understanding individual psychological and behavioral responses during COVID-19: Application of stimulus-organism-response model. Telematics and Informatics, 79, 101966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosleh, S. M., Khraisat, A., Shoqirat, N., & Obeidat, R. (2024). Using the health belief model to predict self-care behaviors among patients with cardiovascular disease post COVID-19 pandemic: A perspective from the United Arab Emirates. SAGE Open Nursing, 10, 23779608241293667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Cathain, A., Thomas, K. J., Drabble, S. J., Rudolph, A., & Hewison, J. (2013). What can qualitative research do for randomised controlled trials? A systematic mapping review. BMJ Open, 3(6), e002889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olapegba, P. O., Chovwen, C. O., Ayandele, O., & Ramos-Vera, C. (2022). Fear of COVID-19 and preventive health behavior: Mediating role of post-traumatic stress symptomology and psychological distress. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(5), 2922–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovretveit, J., Mittman, B. S., Rubenstein, L. V., & Ganz, D. A. (2021). Combining improvement and implementation sciences and practices for the post COVID-19 era. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 36(11), 3503–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliaro, S., Sacchi, S., Pacilli, M. G., Brambilla, M., Lionetti, F., Bettache, K., Bianchi, M., Biella, M., Bonnot, V., Boza, M., Butera, F., Ceylan-Batur, S., Chong, K., Chopova, T., Crimston, C. R., Álvarez, B., Cuadrado, I., Ellemers, N., Formanowicz, M., … &, Zubieta, E. (2021). Trust predicts COVID-19 prescribed and discretionary behavioral intentions in 23 countries. PLoS ONE, 16(3), e0248334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. D., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, K., Stock, F., Haslam, S. A., Capraro, V., Boggio, P., Ellemers, N., Cichocka, A., Douglas, K. M., Rand, D. G., Van der Linden, S., & Cikara, M. (2024). A synthesis of evidence for policy from behavioural science during COVID-19. Nature, 625(7993), 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A. K., & Rao, K. V. (2023). Post-COVID-19 strategic sourcing decisions for escorting stakeholders’ expectations and supplier performance in construction project works. Journal of Global Operations and Strategic Sourcing, 16(2), 224–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saji, J. A., Babu, B. P., & Sebastian, S. R. (2020). Social influence of COVID-19: An observational study on the social impact of post-COVID-19 lockdown on everyday life in Kerala from a community perspective. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 9, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwar, F., Jameel, H. T., & Panatik, S. A. (2023). Understanding public’s adoption of preventive behavior during COVID-19 pandemic using health belief model: Role of psychological capital and health appraisals. SAGE Open, 13(3), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, C. Y., Chang, L. Y., Chang, Y. T., Kuo, D. C. Y., Lu, C. Y., Yen, T. Y., & Gau, S. S. F. (2025). Increased post-COVID-19 behavioral, emotional, and social problems in Taiwanese children. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 124(4), 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strickland, J. C., Reed, D. D., Hursh, S. R., Schwartz, L. P., Foster, R. N. S., Gelino, B. W., LeComte, R. S., Oda, F. S., Salzer, A. R., Schneider, T. D., Dayton, L., Latkin, C., & Johnson, M. W. (2022). Behavioral economic methods to inform infectious disease response: Prevention, testing, and vaccination in the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE, 17(1), e0258828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichman, D., & Underhill, K. (2021). Infected by bias: Behavioral science and the legal response to COVID-19. American Journal of Law & Medicine, 47(2/3), 205–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesema, A. K., Shitu, K., Adugna, A., & Handebo, S. (2021). Psychological impact of COVID-19 and contributing factors of students’ preventive behavior based on HBM in Gondar, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE, 16(10), e0258642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … &, Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollast, R., Schmitz, M., Bigot, A., & Luminet, O. (2021). The theory of planned behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparison of health behaviors between Belgian and French residents. PLoS ONE, 16(11), e0258320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J., Fang, Z., Chen, L., Tang, J., Lu, Q., & Lin, X. (2024). Rethinking the city resilience: COM-B model-based analysis of healthcare accessing behaviour changes affected by COVID-19. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 39(3), 1129–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M., Xia, X., Zhang, X., Xu, L., Yang, D., & Li, S. (2019). Software quality assessment model: A systematic mapping study. Science China Information Sciences, 62, 191101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K. F., Saidi, M. S. B., Bai, X., & Wang, X. (2021). Cruise transport service usage post COVID-19: The health belief model application. Transport Policy, 111, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, P., & Gao, Y. (2022). Public transit travel choice in the post COVID-19 pandemic era: An application of the extended Theory of Planned behavior. Travel Behaviour and Society, 28, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Core Questions | Sub-Questions |

|---|---|

| 1. What? | What behavioral science can be used to explain social behavior? |

| 2. Why? | Why is behavioral science involved in psychological behavior? |

| 3. Where? | Where has behavioral science successfully implemented cognitive behavior? |

| 4. When? | When did behavioral science shift healthcare behavior? |

| 5. Who? | Who had the most impact from behavioral science in evaluating human behavior? |

| Core Concept | Terms |

|---|---|

| Behavioral science | behavioral science*; behavioral paradigm*; behavioral theory*; behavioral concept*; behavioral principle*; behavioral method*; behavioral practice* |

| Post-COVID-19 | post-COVID-19 pandemic*; post-COVID-19 era*; post-COVID-19 world* |

| PCC Element | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Research that involves the target population (individuals, groups, and organizations) | Studies involving unrelated populations (children; public, if not relevant) |

| Concept | Focus on the defined topic/phenomenon in behavioral science (social, psychological, cognitive, healthcare, and human behavior) | Studies not addressing the defined concept (physical health interventions) |

| Context | Conducted in the specified setting (post-COVID-19 pandemic from 2021 to 2024) | Studies outside the context (pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19 in unrelated geographic/temporal contexts) |

| Criteria type | Published in English within a specified timeframe with peer review | Non-English studies, editorials, opinion pieces, and non-peer-reviewed works are examples of non-English study types |

| Criterion | Description |

|---|---|

| The clarity of research questions | Determines whether the study clearly defines its objectives |

| Appropriateness of the methodology | Determines whether the chosen methods suit the research goal |

| Completion of data reporting | Determines whether all data and results are fully disclosed |

| Relevance to the research subject | Determines whether the study aligns with the mapping focus |

| Strategy | Description | What | Why | Where | When | Who |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency analysis | Counting occurrences of specific attributes | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Thematic coding | Grouping studies based on recurring themes or concepts | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Clustering techniques | Organizing studies into clusters based on similarities | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Visualization | Graphical representation of data distribution | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Author (Year) | Study Type | Contribution | Focus | Pertinence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Albarracin and Jung (2021) | Philosophical papers | Model | Psychological behavior in post-COVID-19 research | Full |

| 2. Almaatouq et al. (2024) | Philosophical papers | Theory | Human behavior in post-COVID-19 research | Full |

| 3. Bavel et al. (2020) | Solution proposal | Model | Social behavior in post-COVID-19 research | Full |

| 4. Bonizzato et al. (2022) | Solution proposal | Theory | Cognitive and psychological behavior in post-COVID-19 research | Full |

| 5. Byrne-Davis et al. (2022) | Philosophical papers | Model | Healthcare behavior in post-COVID-19 research | Full |

| 6. Calabria et al. (2022) | Philosophical papers | Model | Cognitive behavior in post-COVID-19 research | Full |

| 7. Daks et al. (2020) | Philosophical papers | Model | Contextual behavior in post-COVID-19 research | Full |

| 8. Grossmann et al. (2022) | Philosophical papers | Theory | Societal behavior in post-COVID-19 research | Full |

| 9. Mishra et al. (2020) | Solution proposal | Lesson learned | Economic behavior in post-COVID-19 research | Full |

| 10. Mladenović et al. (2023) | Philosophical papers | Theory | Emotional behavior in post-COVID-19 research | Full |

| 11. Saji et al. (2020) | Evaluation research | Framework/methods | Social behavior in post-COVID-19 research | Partial |

| Ref. | Origin | Type(s) | Stage(s) | Feedback | Validated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | New | Theorizing | Design | Yes | Experiment |

| 2 | New | Integrative experiments | Design | Yes | Testing theories |

| 3 | Existing | Theoretical framework | Design | No | Conceptualizing |

| 4 | New | Observation | Testing | Yes | ANOVA |

| 5 | New | COREQ guidance | Design | Yes | Rigor |

| 6 | New | Partial correlations | Testing | Yes | Regression |

| 7 | Existing | Predicting | Testing | No | Model |

| 8 | New | Estimating | Design | Yes | Multiple analysis |

| 9 | New | Theoretical framework | Design | No | – |

| 10 | New | Hypothesizing | Design | Yes | Moderation analysis |

| 11 | Existing | Conceptual framework | Design | No | Cross-sectional survey |

| Research Sub-Question | Possible Answer | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| #Studies | % | ||

| 1. What? | New model | 9 | 90.90 |

| 2. Why? | Existing framework | 3 | 27.27 |

| 3. Where? | New evidence | 3 | 27.27 |

| 4. When? | New theory | 9 | 90.90 |

| 5. Who? | New implementer | 3 | 27.27 |

| Core Question | Exemplary Answers Derived from the Extant Literature |

|---|---|

| 1. What? | To discover what social behavior in post-COVID-19 research relates to environmental, living, and technological behaviors (Bonizzato et al., 2022; Byrne-Davis et al., 2022; Daks et al., 2020). |

| 2. Why? | To discover why psychological behavior in post-COVID-19 research encourages maladaptive, well-being-related, and personal behaviors (Mishra et al., 2020; Mladenović et al., 2023). |

| 3. Where? | To discover where cognitive behavior in post-COVID-19 research is dependent on mental, positive, negative, and violent behavior (Almaatouq et al., 2024; Bavel et al., 2020). |

| 4. When? | To determine when healthcare behavior in post-COVID-19 research became associated with physical, mental, and occupational behaviors (Albarracin & Jung, 2021; Bonizzato et al., 2022; Grossmann et al., 2022; Saji et al., 2020). |

| 5. Who? | To discover who is most frequently involved in human behavior in post-COVID-19 research associated with communicative, knowledge, economic, and political behaviors (Bonizzato et al., 2022; Calabria et al., 2022; Daks et al., 2020). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daovisan, H.; Sathiyamas, J.; Choowan, P.; Suwanwong, C. Rethinking Post-COVID-19 Behavioral Science: Old Questions, New Insights. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060831

Daovisan H, Sathiyamas J, Choowan P, Suwanwong C. Rethinking Post-COVID-19 Behavioral Science: Old Questions, New Insights. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):831. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060831

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaovisan, Hanvedes, Jinpitcha Sathiyamas, Phaktada Choowan, and Charin Suwanwong. 2025. "Rethinking Post-COVID-19 Behavioral Science: Old Questions, New Insights" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060831

APA StyleDaovisan, H., Sathiyamas, J., Choowan, P., & Suwanwong, C. (2025). Rethinking Post-COVID-19 Behavioral Science: Old Questions, New Insights. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060831