Psychosocial Profiles of Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) Influencing PrEP Acceptability: A Latent Profile Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Are there heterogeneous subgroups of MSM in relation to psychosocial factors and PrEP acceptability?

- Can these subgroups (if any) be qualitatively defined to provide scope for targeted health communication interventions?

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

2.2. Measures

2.3. Identity Resilience

2.4. Internalised Homonegativity

2.5. LGBTQ+ Connectedness

2.6. Trust in Science

2.7. NHS Attitudes

2.8. Perceived Risk of HIV

2.9. HIV Stigma

2.10. Willingness to Sleep with Someone HIV+ Undetectable

2.11. Risky Sexual Behaviour

2.12. Attitudes Towards Uncommitted Sex (Socio-Sexuality)

2.13. Condom Self-Efficacy

2.14. PrEP Self-Efficacy

2.15. PrEP Acceptability

2.16. Data Analyses

3. Results

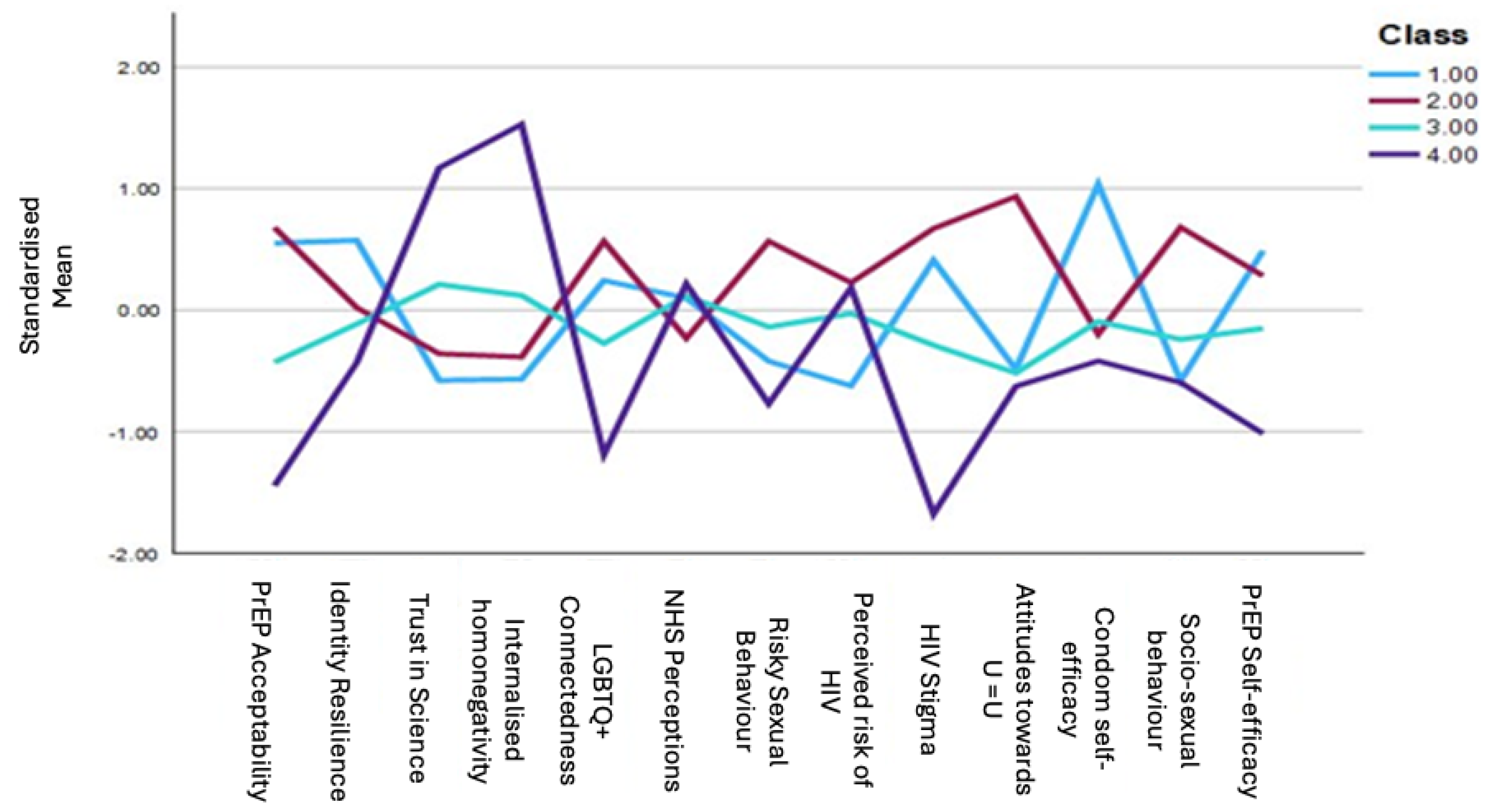

Latent Profile Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bain, L. E., Nkoke, C., & Noubiap, J. J. N. (2017). UNAIDS 90–90–90 targets to end the AIDS epidemic by 2020 are not realistic: Comment on “Can the UNAIDS 90–90–90 target be achieved? A systematic analysis of national HIV treatment cascades”. BMJ Global Health, 2(2), e000227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavinton, B. R., Holt, M., Grulich, A. E., Brown, G., Zablotska, I. B., & Prestage, G. P. (2016). Willingness to act upon beliefs about ‘treatment as prevention’ among australian gay and bisexual men. PLoS ONE, 11(1), e0145847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, M., Adrien, A., Potvin, L., Dassa, C., & Comité Consultatif sur les Attitudes Envers les PVVIH. (2014). Stigmatizing attitudes towards people living with HIV/AIDS: Validation of a measurement scale. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, K. J., Torres, T. S., Hoagland, B., Bezerra, D. R. B., Veloso, V. G., Grinsztejn, B., Clark, J., & Luz, P. M. (2022). Pre-exposure prophylaxis use, HIV knowledge, and internalized homonegativity among men who have sex with men in Brazil: A cross-sectional study. The Lancet Regional Health—Americas, 6, 100152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M., Rodger, A., Asboe, D., Cambiano, V., Clutterbuck, D., Desai, M., Field, N., Harbottle, J., Jamal, Z., McCormack, S., Palfreeman, A., Portman, M., Quinn, K., Tenant-Flowers, M., Wilkins, E., & Young, I. (2019). BHIVA/BASHH guidelines on the use of HIV pre–exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) 2018. HIV Medicine, 20(Suppl. S2), S2–S80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breakwell, G. M., Fino, E., & Jaspal, R. (2022). The identity resilience index: Development and validation in two UK samples. Identity, 22(2), 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breakwell, G. M., Jaspal, R., & Wright, D. B. (2023). Identity resilience, science mistrust, COVID-19 risk and fear predictors of vaccine positivity and vaccination likelihood: A survey of UK and Portuguese samples. Journal of Health Psychology, 28(8), 747–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, R. A., Landrian, A., Nieto, O., & Fehrenbacher, A. (2019). Experiences of anticipated and enacted pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) stigma among latino MSM in Los Angeles. AIDS and Behavior, 23(7), 1964–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. R., Reid, D., Howarth, A. R., Mohammed, H., Saunders, J., Pulford, C. V., Hughes, G., & Mercer, C. H. (2022). Changes in STI and HIV testing and testing need among men who have sex with men during the UK’s COVID-19 pandemic response. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 99, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunting, S. R., Feinstein, B. A., Calabrese, S. K., Hazra, A., Sheth, N. K., Wang, G., & Garber, S. S. (2022). The role of social biases, race, and condom use in willingness to prescribe HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis to MSM: An experimental, vignette-based study. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 91(4), 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, S., Taylor, S. W., Elsesser, S. A., Mena, L., Hickson, D., & Mayer, K. H. (2017). Stigma, medical mistrust, and perceived racism may affect PrEP awareness and uptake in black compared to white gay and bisexual men in Jackson, Mississippi and Boston, Massachusetts. AIDS Care, 29, 1351–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, S. K. (2020). Understanding, contextualizing, and addressing PrEP stigma to enhance PrEP implementation. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 17(6), 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Careja, R., & Harris, E. (2022). Thirty years of welfare chauvinism research: Findings and challenges. Journal of European Social Policy, 32(2), 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P. A., Rose, J., Maher, J., Benben, S., Pfeiffer, K., Almonte, A., Poceta, J., Oldenburg, C. E., Parker, S., Marshall, B. D., Lally, M., Mayer, K., Mena, L., Patel, R., & Nunn, A. S. (2015). A latent class analysis of risk factors for acquiring HIV among men who have sex with men: Implications for implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis programs. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 29(11), 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L. C. (2022). Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and ‘risk’ in the news. Journal of Risk Research, 25(3), 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coukan, F., Murray, K.-K., Papageorgiou, V., Lound, A., Saunders, J., Atchison, C., & Ward, H. (2023). Barriers and facilitators to HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) in Specialist Sexual Health Services in the United Kingdom: A systematic review using the PrEP Care Continuum. HIV Medicine, 24(8), 893–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curley, C. M., Rosen, A. O., Mistler, C. B., & Eaton, L. A. (2022). Pleasure and PrEP: A systematic review of studies examining pleasure, sexual satisfaction, and PrEP. The Journal of Sex Research, 59(7), 848–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M., & Harrington, N. G. (2021). Intention to behavior: Using the integrative model of behavioral prediction to understand actual control of PrEP uptake among gay men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(4), 1817–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawit, R., Predmore, Z., Raifman, J., Chan, P. A., Skinner, A., Napoleon, S., Zanowick-Marr, A., Le Brazidec, D., Almonte, A., & Dean, L. T. (2024). Identifying HIV PrEP attributes to increase PrEP use among different groups of gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men: A latent class analysis of a discrete choice experiment. AIDS and Behavior, 28(1), 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnell, D., Baeten, J. M., Bumpus, N. N., Brantley, J., Bangsberg, D. R., Haberer, J. E., Mujugira, A., Mugo, N., Ndase, P., Hendrix, C., & Celum, C. (2014). HIV protective efficacy and correlates of tenofovir blood concentrations in a clinical trial of PrEP for HIV prevention. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 66(3), 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowell-Day, A., Dobbins, T., Chan, C., Fraser, D., Holt, M., Vaccher, S. J., Clifton, B., Zablotska, I., Grulich, A., & Bavinton, B. R. (2023). Attitudes towards treatment as prevention among PrEP-experienced gay and bisexual men in Australia. AIDS and Behavior, 27(9), 2969–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubov, A., Altice, F. L., & Fraenkel, L. (2018a). An information–motivation–behavioral skills model of PrEP uptake. AIDS and Behavior, 22(11), 3603–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubov, A., Galbo, P., Altice, F. L., & Fraenkel, L. (2018b). Stigma and shame experiences by MSM who take PrEP for HIV prevention: A qualitative study. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(6), 1843–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulai, J., & Jaspal, R. (2024). Social connectedness and identity resilience buffer against minority stress and enhance life satisfaction in ethnic and sexual minorities in the UK. Trends in Psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, L. A., Kalichman, S. C., O’Connell, D. A., & Karchner, W. D. (2009). A strategy for selecting sexual partners believed to pose little/no risks for HIV: Serosorting and its implications for HIV transmission. AIDS Care, 21(10), 1279–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elopre, L., Hussen Sophia, A., Ott, C., Mugavero Michael, J., & Turan, J. M. (2021). A qualitative study: The journey to self-acceptance of sexual identity among young, black MSM in the south. Behavioral Medicine, 47(4), 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsher, M., Szep, Z., Krakower, D., Martinez-Donate, A., Tran, N., & Roth, A. M. (2018). “I don’t need PrEP right now”: A Qualitative exploration of the barriers to PrEP care engagement through the application of the health belief model. AIDS Education and Prevention, 30(5), 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fino, E., Jaspal, R., Lopes, B., Wignall, L., & Bloxsom, C. (2021). The sexual risk behaviors scale (SRBS): Development & validation in a university student sample in the UK. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 44(2), 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowers, P., MacDonald, J., McDaid, L., Nandwani, R., Frankis, J., Young, I., Saunders, J., Clutterbuck, D., Dalrymple, J., Steedman, N., & Estcourt, C. (2022). How can we enhance HIV Pre Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) awareness and access?: Recommendation development from process evaluation of a national PrEP programme using implementation science tools. medRxiv, 2022.06.09.22276189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankis, J., Young, I., Flowers, P., & McDaid, L. (2016). Who will use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and why?: Understanding PrEP awareness and acceptability amongst men who have sex with men in the UK—A mixed methods study. PLoS ONE, 11(4), e0151385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D., Loe, B. S., Chadwick, A., Vaccari, C., Waite, F., Rosebrock, L., Jenner, L., Petit, A., Lewandowsky, S., Vanderslott, S., Innocenti, S., Larkin, M., Giubilini, A., Yu, L.-M., McShane, H., Pollard, A. J., & Lambe, S. (2022). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: The Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychological Medicine, 52(14), 3127–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, D. M., & Meyer, I. H. (2012). Measuring community connectedness among diverse sexual minority populations. Journal of Sex Research, 49(1), 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gafos, M., Horne, R., Nutland, W., Bell, G., Rae, C., Wayal, S., Rayment, M., Clarke, A., Schembri, G., Gilson, R., McOwan, A., Sullivan, A., Fox, J., Apea, V., Dewsnap, C., Dolling, D., White, E., Brodnicki, E., Wood, G., … McCormack, S. (2019). The Context of sexual risk behaviour among men who have sex with men seeking PrEP, and the impact of PrEP on sexual behaviour. AIDS and Behavior, 23(7), 1708–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, A. J., Jaspal, R., Jones, B. A., & McDermott, D. T. (2025a). Predicting PrEP acceptability and self-efficacy among men who have sex with men in the UK: The roles of identity resilience, science mistrust, and stigma. HIV Medicine, 26, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, A. J., Jaspal, R., Jones, B. A., & McDermott, D. T. (2025b). ‘Why are PrEP gays always like this … ’: Psychosocial influences on U.K.-based men who have sex with men’s perceptions and use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. Psychology & Sexuality. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Llario, M. D., Morell-Mengual, V., García-Barba, M., Nebot-García, J. E., & Ballester-Arnal, R. (2023). HIV and STI prevention among spanish women who have sex with women: Factors associated with dental dam and condom use. AIDS and Behavior, 27(1), 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Llario, M. D., Morell-Mengual, V., Ruiz-Palomino, E., & Ballester-Arnal, R. (2019). Factorial structure and psychometric properties of a brief scale of the condom use self-efficacy for spanish-speaking people. Health Education & Behavior, 46(2), 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, S. A. (2018). PrEP stigma: Implicit and explicit drivers of disparity. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 15(2), 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, S. A., Fikslin, R. A., Goldberg, M. H., Peña, S. M., & Radix, A. (2019). Predictors of PrEP uptake among patients with equivalent access. AIDS and Behavior, 23(7), 1917–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C., Hammack, P., Wignall, L., Aggleton, P., Attwood, F., Kong, T., Ryan-Flood, R., Ben Hagai, E., Borba, R., Hall, K., Hiramoto, M., Calogero, R., Elia, J., Foster, A., Galupo, P., Garofalo, R., Holloway, I., Humphreys, T., Motschenbacher, H., … Zucker, K. J. (2025). Statement on the importance of sexuality and gender research. The Journal of Sex Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C., Family, H., Kesten, J., Denford, S., Scott, A., Dawson, S., Scott, J., Sabin, C., Copping, J., Harryman, L., Cochrane, S., & Horwood, J. (2024). Facilitators and barriers to community pharmacy PrEP delivery: A scoping review. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 27(3), e26232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, M., & Müller, P. (2023). Acceptance and adherence to COVID-19 preventive measures are shaped predominantly by conspiracy beliefs, mistrust in science and fear—A comparison of more than 20 psychological variables. Psychological Reports, 126(4), 1742–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hascher, K., Jaiswal, J., Lorenzo, J., LoSchiavo, C., Burton, W., Cox, A., Dunlap, K., Grin, B., Griffin, M., & Halkitis, P. N. (2023). ‘Why aren’t you on PrEP? You’re a gay man’: Reification of HIV ‘risk’ influences perception and behaviour of young sexual minority men and medical providers. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 25(1), 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herek, G. M., Gillis, J. R., & Cogan, J. C. (2009). Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(1), 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, T., Bode, L., & Ng, J. S. C. (2019). Effect of ‘lifestyle stigma’ on public support for NHS-provisioned pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and preventative interventions for HPV and type 2 diabetes: A nationwide UK survey. BMJ Open, 9(8), e029747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jason, L., & Glenwick, D. (2016). Handbook of methodological approaches to community-based research: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jaspal, R. (2018). Enhancing sexual health, self-identity and wellbeing among men who have sex with men: A guide for practitioners. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Jaspal, R. (2020). Social representation, identity and HIV prevention: The case of PrEP among gay men (Z. Davy, A. Cristina Santos, C. Bertone, R. Thoreson, & S. E. Wieringa, Eds.). Sage. Available online: http://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/39731/ (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Jaspal, R., & Bayley, J. (2020). HIV and gay men: Clinical, social and psychological aspects. Springer Singapore Pte. Limited. Available online: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ntuuk/detail.action?docID=6381970 (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Jaspal, R., & Breakwell, G. M. (2022). Identity resilience, social support and internalised homonegativity in gay men. Psychology & Sexuality, 13(5), 1270–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspal, R., & Daramilas, C. (2016). Perceptions of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among HIV-negative and HIV-positive men who have sex with men (MSM). Cogent Medicine, 3(1), 1256850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspal, R., Gardner, S., Zwach, P., Green, M., & Breakwell, G. M. (2022). Trust in science, homonegativity, and HIV stigma: Experimental data from the United Kingdom and Germany. Stigma and Health, 7(4), 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspal, R., Lopes, B., & Maatouk, I. (2019). The attitudes toward pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) scale: Development and validation. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services, 18(2), 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C., Young, I., & Boydell, N. (2020). The people vs. the NHS: Biosexual citizenship and hope in stories of PrEP activism. Somatechnics, 10(2), 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalichman, S. C. (2025). In a world gone mad—Nothing is changing at AIDS and behavior. AIDS and Behavior, 29(4), 1039–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirby, T. (2020). PrEP finally approved on NHS in England. The Lancet, 395(10229), 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, T., & Thornber-Dunwell, M. (2014). Uptake of PrEP for HIV slow among MSM. The Lancet, 383(9915), 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitt, H., Shah, A., Chau, C., Okumu-Camerra, K., Bera, S., Schoemig, V., Mackay, N., Kolawole, T., Ratna, N., Martin, V., Đjuretić, T., & Brown, A. (2024). HIV testing, PrEP, new HIV diagnoses and care outcomes for people accessing HIV services: 2024 report. The annual official statistics data release. (data to end of December 2023). UK Health Security Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Laborde, N. D., Kinley, P. M., Spinelli, M., Vittinghoff, E., Whitacre, R., Scott, H. M., & Buchbinder, S. P. (2020). Understanding PrEP persistence: Provider and patient perspectives. AIDS and Behavior, 24(9), 2509–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, S., Dunn, D. T., Desai, M., Dolling, D. I., Gafos, M., Gilson, R., Sullivan, A. K., Clarke, A., Reeves, I., Schembri, G., Mackie, N., Bowman, C., Lacey, C. J., Apea, V., Brady, M., Fox, J., Taylor, S., Antonucci, S., Khoo, S. H., … Gill, O. N. (2016). Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): Effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. The Lancet, 387(10013), 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDavitt, B., & Mutchler, M. G. (2014). “Dude, you’re such a slut!” Barriers and Facilitators of sexual communication among young gay men and their best friends. Journal of Adolescent Research, 29(4), 464–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmet, M., Callaghan, K., & Lewis, C. (2021). Lots of bots or maybe nots: A process for detecting bots in social media research. International Journal of Market Research, 63(5), 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, K. R., Anton, S. D., & Perri, M. G. (2013). Long-term adherence to health behavior change. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 7(6), 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montess, M. (2020). Demedicalizing the ethics of PrEP as HIV prevention: The social effects on MSM. Public Health Ethics, 13(3), 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadelson, L., Jorcyk, C., Yang, D., Jarratt Smith, M., Matson, S., Cornell, K., & Husting, V. (2014). I just do not trust them: The development and validation of an assessment instrument to measure trust in science and scientists. School Science and Mathematics, 114(2), 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagington, M., & Sandset, T. (2020). Putting the NHS England on trial: Uncertainty-as-power, evidence and the controversy of PrEP in England. Medical Humanities, 46(3), 176–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napper, L. E., Fisher, D. G., & Reynolds, G. L. (2012). Development of the perceived risk of HIV scale. AIDS and Behavior, 16(4), 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberski, D. (2016). Mixture Models: Latent Profile and Latent Class Analysis. In J. Robertson, & M. Kaptein (Eds.), Modern statistical methods for HCI (pp. 275–287). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogaz, D., Logan, L., Curtis, T. J., McDonagh, L., Guerra, L., Bradshaw, D., Patel, P., Macri, C., Murphy, G., Noel Gill, O., Johnson, A. M., Nardone, A., & Burns, F. (2022). PrEP use and unmet PrEP-need among men who have sex with men in London prior to the implementation of a national PrEP programme, a cross-sectional study from June to August 2019. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Halloran, C., Owen, G., Croxford, S., Sims, L. B., Gill, O. N., Nutland, W., & Delpech, V. (2019). Current experiences of accessing and using HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in the United Kingdom: A cross-sectional online survey, May to July 2019. Eurosurveillance, 24(48), 1900693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellowski, J. A., Price, D. M., Desir, A., Golub, S., Operario, D., & Purtle, J. (2023). Using audience segmentation to identify implementation strategies to improve PrEP uptake among at-risk cisgender women: A mixed-methods study protocol. Implementation Science Communications, 4(1), 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penke, L., & Asendorpf, J. (2008). Beyond global sociosexual orientations: A More differentiated look at sociosexuality and its effects on courtship and romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1113–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petherick, A., Goldszmidt, R., Andrade, E. B., Furst, R., Hale, T., Pott, A., & Wood, A. (2021). A worldwide assessment of changes in adherence to COVID-19 protective behaviours and hypothesized pandemic fatigue. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(9), 1145–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piper, K. N., Haardörfer, R., Escoffery, C., Sheth, A. N., & Sales, J. (2021). Exploring the heterogeneity of factors that may influence implementation of PrEP in family planning clinics: A latent profile analysis. Implementation Science Communications, 2(1), 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presanis, A. M., Harris, R. J., Kirwan, P. D., Miltz, A., Croxford, S., Heinsbroek, E., Jackson, C. H., Mohammed, H., Brown, A. E., Delpech, V. C., Gill, O. N., & Angelis, D. D. (2021). Trends in undiagnosed HIV prevalence in England and implications for eliminating HIV transmission by 2030: An evidence synthesis model. The Lancet Public Health, 6(10), e739–e751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, S. R., Lardier, D. T., Boyd, D. T., Gutierrez, J. I., Carasso, E., Houng, D., & Kershaw, T. (2021). Profiles of HIV Risk, sexual power, and decision-making among sexual minority men of color who engage in transactional sex: A latent profile analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, R. N., Brown, J., Mkandawire, G., Folda, L., Böse, K., & Creel, A. H. (2009). Audience Segmentation as a social-marketing tool in health promotion: Use of the risk perception attitude framework in HIV prevention in Malawi. American Journal of Public Health, 99(12), 2224–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, J., Beymer, P., Anderson, D., Van Lissa, C. j., & Schmidt, J. (2018). tidyLPA: An R package to easily carry out latent profile analysis (LPA) using open-source or commercial software. Journal of Open Source Software, 3(30), 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzeszutek, M., & Gruszczyńska, E. (2020). Personality types and subjective well-being among people living with HIV: A latent profile analysis. Quality of Life Research, 29(1), 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seethaler, S., Evans, J. H., Gere, C., & Rajagopalan, R. M. (2019). Science, values, and science communication: Competencies for pushing beyond the deficit model. Science Communication, 41(3), 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, M. (1996). Theory and method in health audience segmentation. Journal of Health Communication, 1, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, F., Magno, L., da Silva, L. A. V., Guimarães, M. D. C., Leal, A. F., Knauth, D., Veras, M. A., de Brito, A. M., Kendall, C., Kerr, L. R. F. S., & Dourado, I. (2023). Perceived risk of HIV infection and acceptability of PrEP among men who have sex with men in Brazil. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 52(2), 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spieldenner, A. (2016). PrEP Whores and HIV prevention: The queer communication of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Journal of Homosexuality, 63(12), 1685–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurk, D., Hirschi, A., Wang, M., Valero, D., & Kauffeld, S. (2020). Latent profile analysis: A review and “how to” guide of its application within vocational behavior research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 120, 103445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torracinta, L., Tanner, R., & Vanderslott, S. (2021). MMR vaccine attitude and uptake research in the United Kingdom: A critical review. Vaccines, 9(4), 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traeger, M. W., Murphy, D., Ryan, K. E., Asselin, J., Cornelisse, V. J., Wilkinson, A. L., Hellard, M. E., Wright, E. J., & Stoové, M. A. (2022). Latent class analysis of sexual behaviours and attitudes to sexually transmitted infections among gay and bisexual men using PrEP. AIDS and Behavior, 26(6), 1808–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpin, R., Smith, J., Watson, L., Heine, B., Dyer, T., & Liu, H. (2022). Latent profiles of stigma and HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among Black sexual minority men: An exploratory study. SN Social Sciences, 2(9), 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underhill, K., Guthrie, K. M., Colleran, C., Calabrese, S. K., Operario, D., & Mayer, K. H. (2018). Temporal Fluctuations in behavior, perceived HIV risk, and willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(7), 2109–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, W., Peterson, J. L., Storholm, E. D., Huebner, D. M., Neilands, T. B., Calabrese, S. K., Rebchook, G. M., Tan, J. Y., Pollack, L., & Kegeles, S. M. (2019). A person-centered approach to HIV-Related protective and risk factors for young black men who have sex with men: Implications for pre-exposure prophylaxis and HIV treatment as prevention. AIDS and Behavior, 23(10), 2803–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J. L. (2019). Applying the information–motivation–behavioral skills model to understand PrEP Intentions and use among men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 23(7), 1904–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, L., Hodson, M., & Josh, J. (2023). Language matters: The importance of person-first language and an introduction to the People First Charter. HIV Medicine, 24(1), 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, T. H. F., Jones, S. S., Wachman, M., Grov, C., Parsons, J. T., & Rendina, H. J. (2019). The impact of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use on sexual anxiety, satisfaction, and esteem among gay and bisexual men. The Journal of Sex Research, 56(9), 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wignall, L., Moseley, R., & McCormack, M. (2023). Autistic traits of people who engage in pup play: Occurrence, characteristics and social connections. The Journal of Sex Research, 62, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L., Wu, Y., Meng, S., Hou, J., Fu, R., Zheng, H., He, N., Wang, M., & Meyers, K. (2019). Risk behavior not associated with self-perception of PrEP candidacy: Implications for designing PrEP services. AIDS and Behavior, 23(10), 2784–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | Total | Latent Profiles | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| (N = 500) | (N = 75) | (N = 181) | N = (185) | (N = 59) | |

| Current PrEP Use | |||||

| Using or used PrEP | 41.8% (n = 209) | 24.0% (n = 18) | 70.7% (n = 128) | 29.2% (n = 54) | 15.3% (n = 9) |

| Never used PrEP | 58.2% (n = 291) | 76.0% (n = 57) | 29.3% (n = 53) | 70.8% (n = 131) | 84.7% (n = 50) |

| PrEP Dosage | |||||

| Daily PrEP | 19.8% (n = 99) | 6.7% (n = 5) | 38.7% (n = 70) | 10.8% (n = 20) | 6.8% (n = 4) |

| Event-Based PrEP | 13.2% (n = 66) | 6.7% (n = 5) | 21.5% (n = 39) | 10.3% (n = 19) | 5.1% (n = 3) |

| No longer using PrEP | 7.6% (n = 38) | 10.7% (n = 8) | 7.7% (n = 14) | 7.6% (n = 14) | 3.4% (n = 2) |

| Other | 1.2% (n = 6) | 0.0% (n = 0) | 2.8% (n = 5) | 0.5% (n = 1) | 0.0% (n = 0) |

| Never used PrEP | 58.2% (n = 291) | 76.0% (n = 57) | 29.3% (n = 53) | 70.8% (n = 131) | 84.7% (n = 50) |

| Relationship Status | |||||

| Single | 45.8% (n = 229) | 32% (n = 24) | 56.9% (n = 103) | 39.5% (n = 73) | 49.2% (n = 29) |

| In a relationship (monogamous) | 31.4% (n = 157) | 49.3% (n = 37) | 11.6% (n = 21) | 42.7% (n = 79) | 33.9% (n = 20) |

| In a relationship (non-monogamous) | 22.4% (n = 112) | 18.7% (n = 14) | 31.5% (n = 57) | 17.3% (n = 32) | 15.3% (n = 9) |

| Other | 0.4% (n = 2) | 0.0% (n = 0) | 0.0% (n = 0) | 0.5% (n = 1) | 1.7% (n = 1) |

| Sexuality | |||||

| Gay | 73.2% (n = 366) | 74.7% (n = 56) | 83.4% (n = 151) | 69.7% (n = 129) | 50.8% (n = 30) |

| Bisexual | 25% (n = 125) | 24.0% (n = 18) | 13.3% (n = 24) | 29.2% (n = 54) | 49.2% (n = 29) |

| Other | 1.8% (n = 9) | 1.3% (n = 1) | 3.3% (n = 6) | 1.1% (n = 2) | 0.0% (n = 0) |

| Gender Identity | |||||

| Same as birth (i.e., Cisgender Male) | 98.4% (492) | 98.7% (n = 74) | 96.7% (n = 175) | 99.5% (n = 184) | 100% (n = 59) |

| Different from birth (i.e., Non-Binary) | 1.6% (n = 8) | 1.3% (n = 1) | 3.3% (n = 6) | 0.5% (n = 1) | 0.0% (n = 0) |

| Outness | |||||

| Out to everyone! | 73% (n = 365) | 77.3% (n = 58) | 86.7% (n = 157) | 67.6% (n = 125) | 42.4% (n = 25) |

| Not out at all! | 3% (n = 15) | 0.0% (n = 0) | 0.6% (n = 1) | 2.7% (n = 5) | 15.3% (n = 9) |

| Out to some people! | 24% (n = 120) | 22.7% (n = 17) | 12.7% (n = 23) | 29.7% (n = 55) | 42.4% (n = 25) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 91.2% (n = 456) | 90.7% (n = 68) | 91.7% (n = 166) | 94.1% (n = 174) | 81.4% (n = 48) |

| Mixed | 2.6% (n = 13) | 4.0% (n = 3) | 2.2% (n = 4) | 1.6% (n = 3) | 5.1% (n = 3) |

| Asian/British Asian | 3.4% (n = 17) | 1.3% (n = 1) | 2.8% (n = 5) | 3.2% (n = 6) | 8.5% (n = 5) |

| Black | 1.4% (n = 7) | 2.7% (n = 2) | 1.7% (n = 3) | 0.0% (n = 0) | 3.4% (n = 2) |

| Other | 1.4% (n = 7) | 1.3% (n = 1) | 1.7% (n = 3) | 1.1% (n = 2) | 1.7% (n = 1) |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Never married | 75.2% (376) | 74.7% (n = 56) | 79.6% (n = 144) | 71.9% (n = 133) | 72.9% (n = 43) |

| Married | 19.2% (n = 96) | 20.0% (n = 15) | 15.5% (n = 28) | 21.6% (n = 40) | 22.0% (n = 13) |

| Divorced | 3.8% (n = 19) | 2.7% (n = 2) | 4.4% (n = 8) | 4.3% (n = 8) | 1.7% (n = 1) |

| Widowed | 1.0% (n = 5) | 0.0% (n = 0) | 0.6% (n = 1) | 1.6% (n = 3) | 1.7% (n = 1) |

| Other | 0.8% (n = 4) | 2.7% (n = 2) | 0.0% (n = 0) | 0.5% (n = 1) | 1.7% (n = 1) |

| Education | |||||

| GCSE | 5.4% (n = 27) | 2.7% (n = 2) | 1.7% (n = 3) | 8.1% (n = 15) | 11.9% (n = 7) |

| A level | 17.4% (n = 87) | 14.7% (n = 11) | 12.7% (n = 23) | 20.5% (n = 38) | 25.4% (n = 15) |

| Undergraduate | 39.2% (n = 196) | 42.7% (n = 32) | 35.4% (n = 64) | 42.2% (n = 78) | 37.3% (n = 22) |

| Postgraduate | 26.8% (n = 134) | 33.3% (n = 25) | 33.1% (n = 60) | 19.5% (n = 36) | 22.0% (n = 13) |

| PhD/Prof Doc | 11.2% (n = 56) | 6.7% (n = 5) | 17.1% (n = 31) | 9.7% (n = 18) | 3.4% (n = 2) |

| UK Location | |||||

| England | 84.2% (n = 421) | 80% (n = 60) | 85.6% (n = 155) | 83.2% (n = 154) | 88.1% (n = 52) |

| Scotland | 9.8% (n = 49) | 8.0% (n = 6) | 9.9% (n = 18) | 10.3% (n = 19) | 10.2% (n = 6) |

| Wales | 4.0% (n = 20) | 8.0% (n = 6) | 2.2% (n = 4) | 4.9% (n = 9) | 1.7% (n = 1) |

| Northern Ireland | 2.0% (n = 10) | 4.0% (n = 3) | 2.2% (n = 4) | 1.6% (n = 3) | 0.0% (n = 0) |

| Age | Aged 18–73 | Aged 20–73 | Aged 18–58 | Aged 21–66 | Aged 18–64 |

| (M = 35.61, SD = 9.95) | (M = 34.4, SD = 11.02) | (M = 34.02, SD = 7.97) | (M = 36.85, SD = 10.33) | (M = 37.53, SD = 12.0) | |

| Total Sample (N = 500) | Mean | SD | α | 95% Confidence Boundaries | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Perceived risk of HIV | 2.81 | 0.67 | 0.8 | 0.78 | 0.83 |

| HIV stigma | 4.33 | 0.52 | 0.91 | 0.9 | 0.93 |

| Condom use self-efficacy | 3.73 | 0.65 | 0.7 | 0.66 | 0.74 |

| Identity resilience | 3.51 | 0.52 | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.86 |

| LGBTQ+ connectedness | 2.76 | 0.82 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

| NHS Perceptions | 2.27 | 0.64 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.87 |

| Trust in science | 1.92 | 0.55 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.91 |

| Risky sexual behaviour | 2.94 | 0.77 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.72 |

| Socio-sexual behaviour | 5.71 | 1.57 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.88 |

| Internalised homonegativity | 1.59 | 0.73 | 0.83 | 0.8 | 0.85 |

| Attitudes towards U = U | 3.13 | 1.89 | Single item measure | ||

| PrEP self-efficacy | 3.02 | 0.54 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.81 |

| PrEP acceptability | 3.79 | 0.46 | 0.8 | 0.77 | 0.82 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Perceived risk of HIV | 1 | |||||||||||

| 2 | HIV stigma | 0.04 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 3 | Condom self-efficacy | −0.19 ** | 0.10 * | 1 | |||||||||

| 4 | Identity resilience | −0.23 ** | 0.09 | 0.25 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| 5 | LGBTQ+ Connectedness | 0.03 | 0.40 ** | 0.04 | 0.18 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 6 | NHS attitudes | −0.14 ** | −0.12 ** | 0.17 ** | 10 * | 0.65 | 1 | ||||||

| 7 | (Mis)Trust in science | 0.09 | −0.41 ** | −0.24 ** | −0.18 ** | −0.29 ** | 0.02 | 1 | |||||

| 8 | Risky sexual behaviour | 0.06 | 0.23 ** | −0.19 ** | <0.01 | 0.23 ** | −0.10 * | −0.11 * | 1 | ||||

| 9 | Sociosexual orientation | 0.26 ** | 0.31 ** | −0.14 ** | 0.02 | 0.19 ** | −0.05 | −0.12 ** | 0.49 ** | 1 | |||

| 10 | Internalised homonegativity | 0.14 ** | −0.42 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.31 ** | −0.03 | 0.23 ** | −0.18 ** | −0.17 ** | 1 | ||

| 11 | Sex with HIV+ (undetectable) | 0.08 | 0.38 ** | −0.17 ** | < 0.01 | 0.29 ** | −0.15 ** | −0.14 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.34 ** | −0.21 ** | 1 | |

| 12 | PrEP self-efficacy | −0.08 | 0.25 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.17 ** | −0.25 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.20 ** | −0.31 ** | 0.18 ** | 1 |

| 13 | PrEP acceptability | −0.04 | 0.55 ** | 0.12 * | 0.14 ** | 0.42 ** | −0.17 ** | −0.47 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.23 ** | −0.32 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.35 ** |

| Model | Classes | AIC | BIC | Entropy | Prob_min | Prob_max | n_min | n_max | BLRT_p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 18,485.19 | 18,594.77 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1 | 2 | 17,807.68 | 17,976.26 | 0.78 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.35 | 0.65 | 0.01 |

| 1 | 3 | 17,475.46 | 17,703.05 | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.13 | 0.45 | 0.01 |

| 1 | 4 | 17,391.57 | 17,678.17 | 0.8 | 0.75 | 0.94 | 0.12 | 0.37 | 0.01 |

| 1 | 5 | 17,360.68 | 17,706.28 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.96 | 0.1 | 0.36 | 0.01 |

| Profile | (1) PrEP Ambivalent | (2) PrEP Accepting | (3) PrEP Hesitant | (4) PrEP Rejecting | ANOVA | Post hoc Bonferroni Correction † | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F (3, 496) | η2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Significant difference: | ||||||||||||||

| Perceived risk of HIV | 2.4 | (0.63) | 2.96 | (0.62) | 2.79 | (0.62) | 2.94 | (0.9) | 14.64 ** | 0.08 | 2,3,4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| HIV stigma | 4.54 | (0.38) | 4.67 | (0.19) | 4.18 | (0.39) | 3.46 | (0.51) | 203.89 ** | 0.55 | 4 | 3,4 | 1,2,4 | 1,2,3 |

| Condom self-efficacy | 4.4 | (0.47) | 3.6 | (0.62) | 3.67 | (0.57) | 3.46 | (0.63) | 41.08 ** | 0.2 | 2,3,4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Identity resilience | 3.8 | (0.48) | 3.52 | (0.49) | 3.45 | (0.5) | 3.28 | (0.56) | 13.71 ** | 0.08 | 2,3,4 | 1,4 | 1 | 1,2 |

| LGBTQ+ Connectedness | 2.94 | (0.75) | 3.22 | (0.59) | 2.4 | (1.04) | 1.35 | (1.3) | 72.06 ** | 0.3 | 3,4 | 3,4 | 1,2,4 | 1,2,3 |

| NHS attitudes | 2.34 | (0.6) | 2.13 | (0.64) | 2.35 | (0.62) | 2.41 | (0.65) | 5.4 ** | 0.03 | 3 | 2 | ||

| (Mis)Trust in science | 1.6 | (0.42) | 1.72 | (0.48) | 2.04 | (0.43) | 2.57 | (0.63) | 62.92 ** | 0.28 | 3,4 | 3,4 | 1,2,4 | 1,2,3 |

| Risky sexual behaviour | 2.62 | (0.68) | 3.38 | (0.64) | 2.83 | (0.7) | 2.35 | (0.74) | 46.7 ** | 0.22 | 2 | 1,3,4 | 2,4 | 2,3 |

| Sociosexual orientation | 4.78 | (0.23) | 6.78 | (1.27) | 5.33 | (1.38) | 4.77 | (1.5) | 65.12 ** | 0.28 | 2 | 1,3,4 | 2 | 2 |

| Internalised homonegativity | 1.17 | (0.35) | 1.3 | (0.44) | 1.67 | (0.62) | 2.71 | (0.93) | 103.05 ** | 0.38 | 3,4 | 3,4 | 1,2,4 | 1,2,3 |

| Sex with HIV+ (undetectable) | 2.21 | (0.48) | 4.9 | (1.16 | 2.16 | (0.62) | 1.95 | (1.44) | 163.77 ** | 0.5 | 2 | 1,3,4 | 2 | 2 |

| PrEP self-efficacy | 3.28 | (0.5) | 3.17 | (0.48) | 2.94 | (0.47) | 2.48 | (0.5) | 40.11 ** | 0.2 | 3,4 | 3,4 | 1,2,4 | 1,2,3 |

| PrEP acceptability | 4.04 | (0.34) | 4.1 | (0.31) | 3.59 | (0.31) | 3.12 | (0.35) | 184.86 ** | 0.53 | 3,4 | 3,4 | 1,2,4 | 1,2,3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gifford, A.J.; Jaspal, R.; Jones, B.A.; McDermott, D.T. Psychosocial Profiles of Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) Influencing PrEP Acceptability: A Latent Profile Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 818. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060818

Gifford AJ, Jaspal R, Jones BA, McDermott DT. Psychosocial Profiles of Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) Influencing PrEP Acceptability: A Latent Profile Analysis. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):818. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060818

Chicago/Turabian StyleGifford, Anthony J., Rusi Jaspal, Bethany A. Jones, and Daragh T. McDermott. 2025. "Psychosocial Profiles of Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) Influencing PrEP Acceptability: A Latent Profile Analysis" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 818. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060818

APA StyleGifford, A. J., Jaspal, R., Jones, B. A., & McDermott, D. T. (2025). Psychosocial Profiles of Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) Influencing PrEP Acceptability: A Latent Profile Analysis. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 818. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060818