Social–Emotional and Educational Needs of Higher Education Students with High Abilities: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. High Ability in Higher Education

1.2. Underachievement

1.3. Social–Emotional and Educational Needs

1.4. Interventions to Reduce Underachievement

1.4.1. Interventions Targeting Students

1.4.2. Interventions Targeting Teachers and Student Advisors

1.5. Current Study

- Which specific social–emotional needs and educational needs of students with high abilities in higher education are identified in research?

- What types of interventions have been developed to reduce underachievement among students with high abilities in higher education?

- Which needs are addressed by these interventions?

- To what extent do these interventions impact the reduction of underachievement?

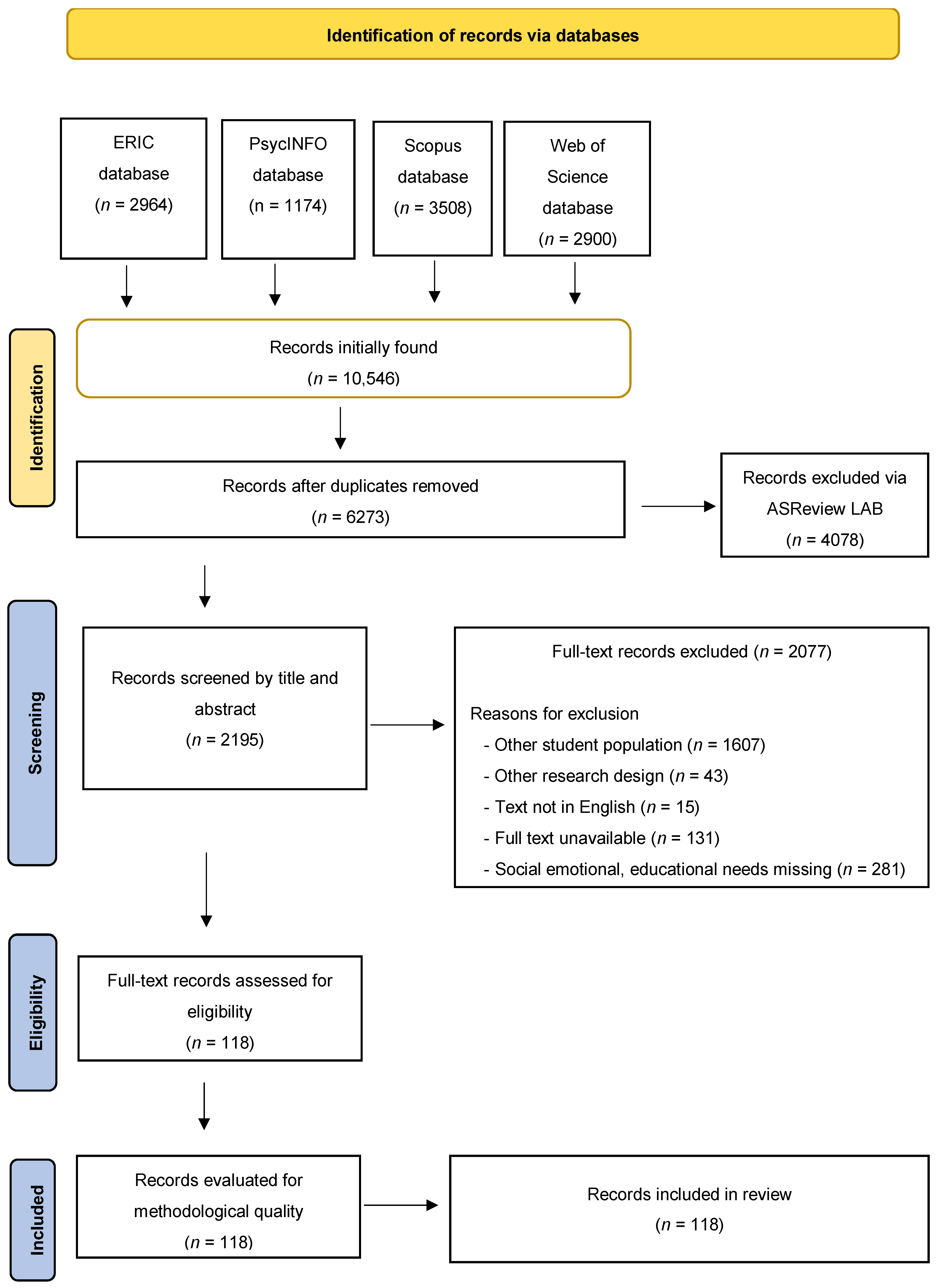

2. Method

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identified Needs of Higher Education Students with High Abilities

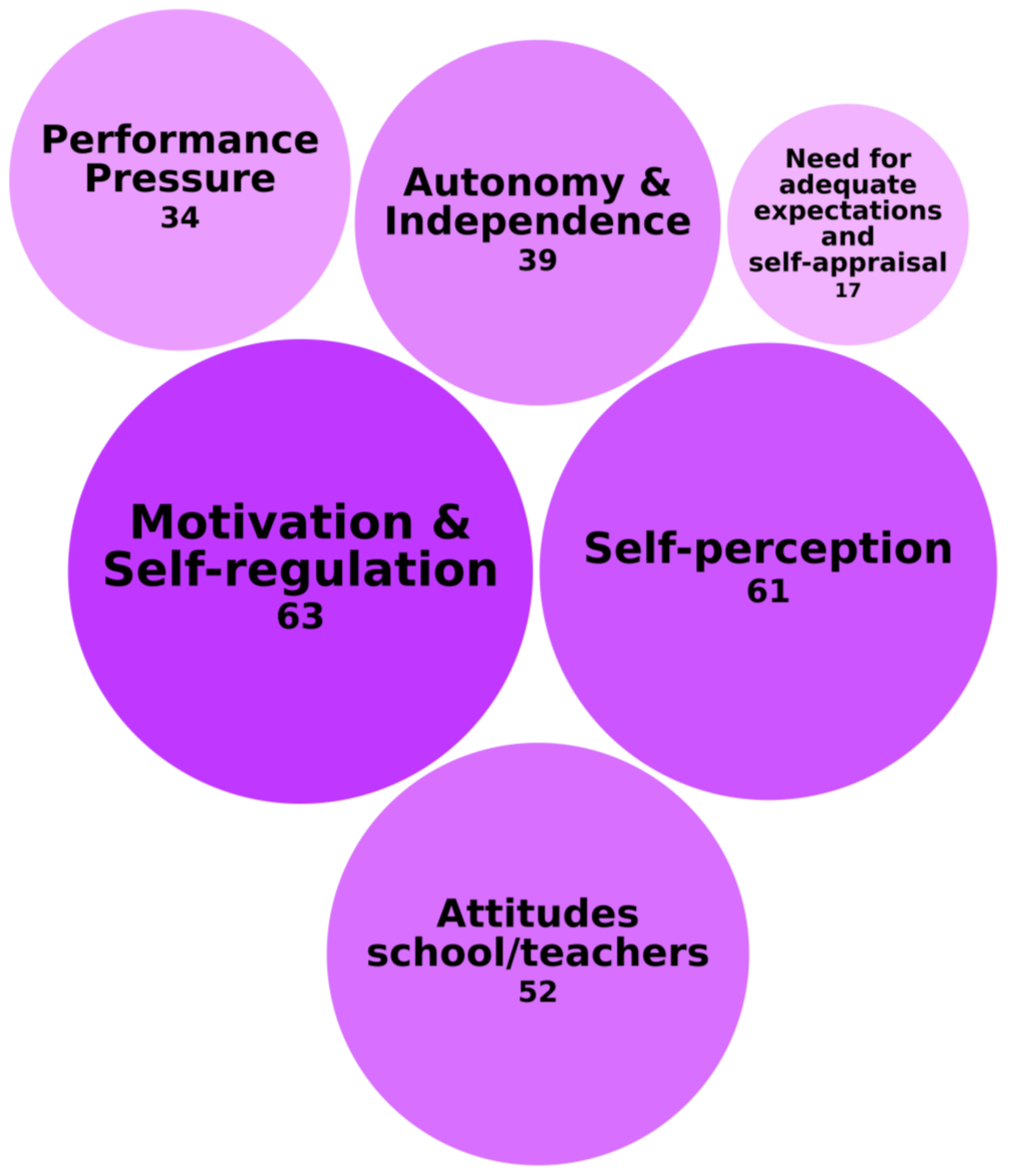

3.2. Identified Social–Emotional Needs of Students with High Abilities

3.2.1. Self-Perception, Motivation, and Performance Expectations

3.2.2. Psychological Well-Being and Emotional Regulation

3.2.3. Social Integration and Acceptance

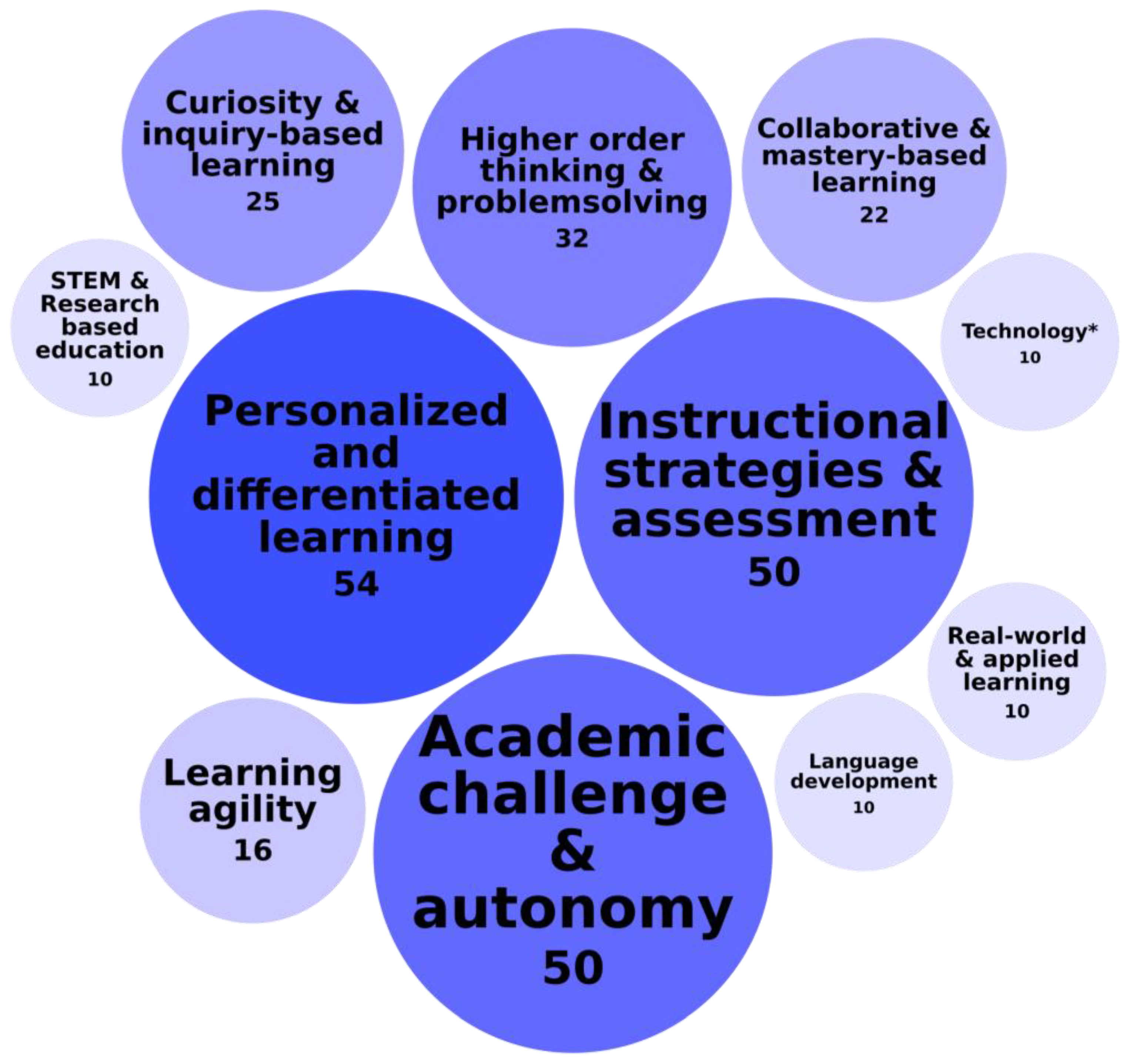

3.3. Identified Educational Needs of Students with High Abilities

3.3.1. Curriculum Design and Instructional Strategies

3.3.2. Academic and Social Support Systems

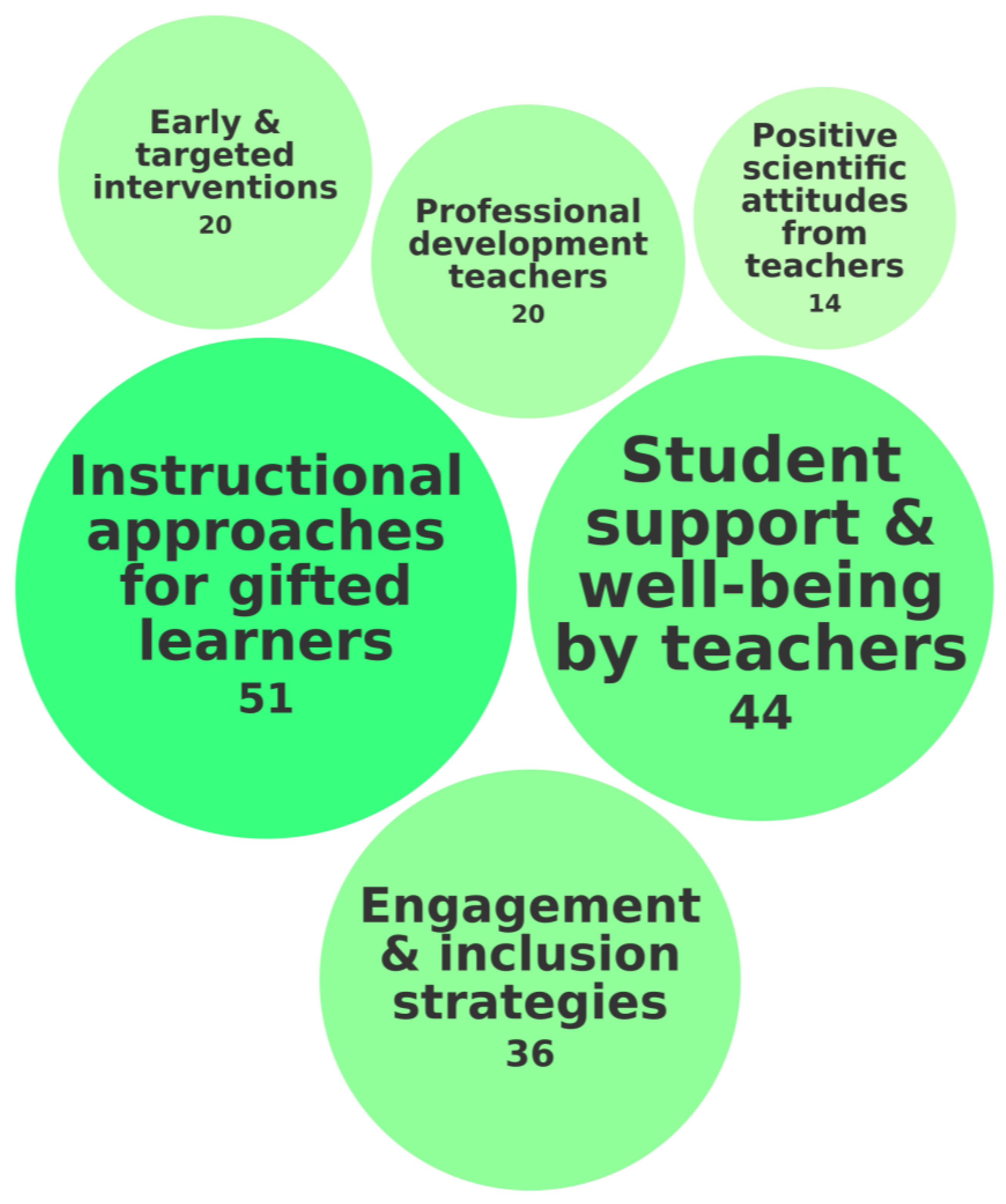

3.3.3. Teacher Training and Pedagogical Expertise

3.4. Types of Interventions

3.4.1. Interventions Targeted at Students

3.4.2. Interventions Targeted at Student Advisors and/or Teachers

3.5. Needs Addressed by Interventions

3.5.1. Needs Addressed by Interventions Targeting Students

3.5.2. Needs Addressed by Interventions Targeting Student Advisors and/or Teachers

3.6. Impact of Interventions on Reduction of Underachievement

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths, Limitations and Future Research

4.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Social–Emotional Needs per Category

| Social–Emotional Needs | Hits |

| Category 1: Self-Perception, Motivation, and Performance Expectations | |

| Motivation and self-regulation | 63 |

| Self-perception, confidence, self-efficacy | 61 |

| Attitudes toward school and teachers | 52 |

| Desire for autonomy/independence learning | 39 |

| Coping with performance pressure | 34 |

| Need for adequate expectations and self-appraisal | 17 |

| Category 2: Social Integration and Acceptance | |

| Sense of belonging and social acceptance | 45 |

| Social interactions, friendships, and relations | 35 |

| Trust and emotional validation from others | 32 |

| Parental and family expectations | 20 |

| Social perceptions and misalignment | 19 |

| Leadership and social responsibility | 17 |

| Category 3: Psychological Well-Being and Emotional Regulation | |

| Need for support and understanding | 48 |

| Sense of control over success and failure | 46 |

| Anxiety and stress management | 36 |

| Identity formation and career choices | 33 |

| Emotional intelligence and regulation | 18 |

| Spiritual and existential well-being | 10 |

| Emotional overexcitability and sensitivity | 10 |

| Need for stability | 6 |

Appendix B

Educational Needs per Category

| Educational Needs | Hits |

| Category 1: Curriculum Design and Instructional Strategies | |

| Personalized and differentiated learning | 54 |

| Instructional strategies and (dynamic or formative) assessment | 50 |

| Academic challenge and autonomy | 50 |

| Higher-order thinking, critical thinking, and problem-solving | 32 |

| Curiosity, active and inquiry-based learning | 25 |

| Collaborative and mastery-based learning | 22 |

| Learning agility/study skills | 16 |

| Language and literacy development | 10 |

| STEM and research-based education | 10 |

| Technology-enhanced learning | 10 |

| Real-world and applied learning | 10 |

| Category 2: Academic and Social Support Systems | |

| Academic support and flexibility | 48 |

| Mentorship and career guidance | 41 |

| Counseling and mental health support | 35 |

| Research and experiential learning opportunities | 28 |

| University transition and social integration | 26 |

| Peer-to-peer learning assistance/feedback | 15 |

| Mastery experiences | 9 |

| University campus experiences | 9 |

| Financial and accessibility support | 6 |

| Category 3: Teacher Training and Pedagogical Expertise | |

| Instructional approaches for gifted learners | 51 |

| Student support and well-being (by teachers) | 44 |

| Engagement and inclusion strategies | 36 |

| Professional development teachers | 20 |

| Early and targeted interventions | 20 |

| Positive scientific attitude from teachers | 14 |

References

- Abdallah, M. M. (2024). New trends in gifted education: For PhD degree students (Curriculum & instruction of TESOL/TEFL). Online Submission.

- Abeysekera, I. (2014). Giftedness and talent in university education: A review of issues and perspectives. Gifted and Talented International, 29(1–2), 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, H. S., & Movassagh, H. (2017). On the relationship among critical thinking, language learning strategy use and university achievement of Iranian English as a foreign language majors. Language Learning Journal, 45(3), 382–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshari, H., Amirian, Z., & Tavakoli, M. (2020). Applying group dynamic assessment procedures to support EFL writing development: Learner achievement, learners’ and teachers’ perceptions. Journal of Writing Research, 11(3), 445–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgül, G. (2021). Teachers’ metaphors and views about gifted students and their education. Gifted Education International, 37(3), 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A., Saleem, N., & Rahman, N. (2021). Emotional intelligence of university students: Gender based comparison. Bulletin of Education and Research, 43(1), 255–265. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khayat, M. M., Al-Hrout, M. A., & Hyassat, M. A. (2017). Academically gifted undergraduate students: Their preferred teaching strategies. International Education Studies, 10(7), 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Almousa, N. A., Al-Shobaki, N., Arabiyat, R., Al-Shatrat, W., Al-Shogran, R., & Sulaiman, B. A. (2022). Academic problems facing high achieving students at universities. Pegem Journal of Education and Instruction, 12(4), 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Almukhambetova, A., & Hernández-Torrano, D. (2020). Gifted students’ adjustment and underachievement in university. An exploration from the self-determination theory perspective. Gifted Child Quarterly, 64(2), 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almukhambetova, A., & Hernandez-Torrano, D. (2021). On being gifted at university: Academic, social, emotional, and institutional adjustment in Kazakhstan. Journal of Advanced Academics, 32(1), 70–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtani, A. A. (2021). Reading English as a foreign language: The interplay of abilities and strategies. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 10(3), 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shabatat, M. A., Abbas, M., & Nizam, I. H. (2010). The direct and indirect effects of the achievement motivation on nurturing intellectual giftedness. International Journal of Educational and Pedagogical Sciences, 4(7), 1613–1621. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ta’ani, W. M. M., & Hamadneh, M. A. (2023). The reality of learning motivation among gifted students in light of active learning strategies. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology, 11(3), 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R. J., Imberman, S. A., & Lovenheim, M. F. (2020). Recruiting and supporting low-income, high-achieving students at flagship universities. Economics of Education Review, 74, 101923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtiyani, S. C., Shamsi, M., & Jalilian, V. (2013). Evaluating the influencing factors of educational decline in gifted and ordinary students and their suggested solutions. Middle East Journal of Scientific Research, 16(9), 1285s–1291s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avsec, S., & Savec, V. F. (2021). Pre-service teachers’ perceptions of, and experiences with, technology-enhanced transformative learning towards education for sustainable development. Sustainability, 13(18), 10443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, S. K., Choate, S. M., & Bliss, S. L. (2006). Perceptions of developmental, social, and emotional issues in giftedness: Are they realistic? Roeper Review, 29(1), 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, S. K., McCallum, R. S., Bell, S. M., Cochran, J. L., & Sawyer, S. C. (2010). Foreign language learning aptitudes, attitudes, attributions, and achievement of postsecondary students identified as gifted. Journal of Advanced Academics, 22(1), 130–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakx, A., Van Houtert, T., Brand, M. v. d., & Hornstra, L. (2019). A comparison of high-ability pupils’ views vs. regular ability pupils’ views of characteristics of good primary school teachers. Educational Studies, 45(1), 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1989). Regulation of cognitive processes through perceived self-efficacy. Developmental Psychology, 25(5), 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational Psychologist, 28(2), 117–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, J. M., Kim, H., Eno, C. A., & Guadagno, R. E. (2018). Matching abilities to careers for others and self: Do gender stereotypes matter to students in advanced math and science classes? Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 79(1–2), 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baslanti, U., & McCoach, D. B. (2006). Factors related to the underachievement of university students in Turkey. Roeper Review, 28(4), 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudson, T. G., & Preckel, F. (2013). Teachers’ implicit personality theories about the gifted: An experimental approach. School Psychology Quarterly, 28(1), 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, C. A., Job, V., & Hannover, B. (2023). Who gets to see themselves as talented? Biased self-concepts contribute to first-generation students’ disadvantage in talent-focused environments. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 108, 104501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beduna, K., & Perrone-McGovern, K. M. (2016). Relationships among emotional and intellectual overexcitability, emotional IQ, and subjective well-being. Roeper Review, 38(1), 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S. M., & McCallum, R. S. (2012). Do foreign language learning, cognitive, and affective variables differ as a function of exceptionality status and gender? International Education, 42(1), 86–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Eliyahu, A. (2019). A situated perspective on self-regulated learning from a person-by-context perspective. High Ability Studies, 30(1), 199–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R. (2009). Academic self-concept among business students in a recruiting university: Definition, measurement and potential effects. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 33(2), 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergold, S., Hastall, M. R., & Steinmayr, R. (2021). Do mass media shape stereotypes about intellectually gifted individuals? Two experiments on stigmatization effects from biased newspaper reports. Gifted Child Quarterly, 65(1), 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boazman, J., & Sayler, M. (2011). Personal well-being of gifted students following participation in an early college-entrance program. Roeper Review, 33(2), 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodewes, D., Diepstraten, I., Weterings-Helmons, A., & Bakx, A. W. E. A. (2021). Hoogbegaafde studenten laten floreren in het hoger onderwijs, Fontys TEC-project, deelstudie 2 van 3. Available online: https://www.fontys.nl/Over-Fontys/Nieuws-tonen-op/rapportage-deelonderzoek-2-def-met-cover.htm (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- Campbell, A. (2019). How do students’ beliefs about mathematics ability change in their first year at university? Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning, 7, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K. C., & Fuqua, D. R. (2008). Factors predictive of student completion in a collegiate honors program. Journal of College Student Retention, 10(2), 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canaan, S., Deeb, A., & Mouganie, P. (2022). Adviser value added and student outcomes: Evidence from randomly assigned college advisers. American Economic Journal-Economic Policy, 14(4), 151–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, S. M., Henderson, C. E., Henderson, J., & Fleming, D. L. (2002). Socioemotional factors contributing to adjustment among early-entrance college students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 46(2), 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carman, C. A. (2013). Comparing apples and oranges. Fifteen years of definitions of giftedness in research. Journal of Advanced Academics, 24(1), 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C., Schwitzer, A., Paredes, T., & Grothaus, T. (2018). Honors college students’ adjustment factors and academic success: Advising implications. NACADA Journal, 38(2), 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clasen, D. R. (2006). Project stream: A 13-year follow-up of a pre-college program for middle-and high-school underrepresented gifted. Roeper Review, 29(1), 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenders, S. (2024). De onderwijs-en sociaal-emotionele behoeften van studenten met kenmerken van hoogbegaafdheid in het wetenschappelijk onderwijs in Nederland [Unpublished Master’s thesis, Radboud University]. [Google Scholar]

- Conejeros-Solar, M. L., & Gómez-Arízaga, M. P. (2015). Gifted students’ characteristics, persistence, and difficulties in college. Roeper Review, 37(4), 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Credé, M., & Niehorster, S. (2012). Adjustment to college as measured by the student adaptation to college questionnaire: A quantitative review of its structure and relationships with correlates and consequences. Educational Psychology Review, 24(1), 133–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, T. L., Cross, J. R., Mammadov, S., Ward, T. J., Neumeister, K. S., & Andersen, L. (2018). Psychological heterogeneity among honors college students. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 41(3), 242–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1994). Promoting self-determined education. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 38(1), 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deibl, I., & Zumbach, J. (2023). Pre-service teachers’ beliefs about neuroscience and education—Do freshmen and advanced students differ in their ability to identify myths? Psychology Learning and Teaching, 22(1), 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derado, J., Garner, M. L., & Tran, T. H. (2016). Point reward system: A method of assessment that accommodates a diversity of student abilities and interests and enhances learning. Primus, 26(3), 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, O. A., Pereira, N., & Peterson, J. S. (2020). Telling a tale: How underachievement develops in gifted girls. Gifted Child Quarterly, 64(2), 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Soto, C., Labajo, V., & Labrador-Fernandez, J. (2023). The relationship between impostor phenomenon and transformational leadership among students in STEM. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues, 42(13), 11195–11206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S., & Molden, D. C. (2017). Mindsets: Their impact on competence motivation and acquisition. In A. J. Elliot, C. S. Dweck, & D. S. Yeager (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation: Theory and application (2nd ed., pp. 135–154). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C. S., & Yeager, D. S. (2019). Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddy, S. L., Crowe, A. J., Wenderoth, M. P., & Freeman, S. (2013). How should we teach tree-thinking? An experimental test of two hypotheses. Evolution: Education and Outreach, 6(1), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Eiselen, R., & Geyser, H. (2003). Factors distinguishing between achievers and at risk students: A qualitative and quantitative synthesis. South African Journal of Higher Education, 17(2), 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellala, Z. K., Attiyeh, J. H. A., Alnoaim, J. A., Alsalhi, N. R., Alqudah, H., Al-Qatawneh, S., Alakashee, B., & Abdelkader, A. F. I. (2022). The role of students’ agility and students’ interest in the linguistic intelligence among gifted students in higher education institutions. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 2022(100), 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsamanoudy, G. E. A., & Abdelaziz, N. S. (2020). Teaching strategies for gifted students in interior design program. Journal for the Education of Gifted Young Scientists, 8(2), 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, S. C. (2017). Science teaching attitudes and scientific attitudes of pre-service teachers of gifted students. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(6), 164–170. [Google Scholar]

- Fewster-Young, N., & Corcoran, P. A. (2023). Personalising the student first year experience—An evaluation of a Staff Student Buddy System. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 20(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, C. J., & Krause, J. M. (2014). Lost confidence and potential: A mixed methods study of underachieving college students’ sources of self-efficacy. Social Psychology of Education: An International Journal, 17(2), 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, F. (2004). Transforming gifts into talents: The DMGT as a developmental theory. High Ability Studies, 15(2), 119–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, F. (2021). Implementing the DMGT’s constructs of giftedness and talent: What, why, and how? In S. R. Smith (Ed.), Handbook of giftedness and talent development in the Asia-Pacific (pp. 71–99). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, F. (2023). The differentiated model of giftedness and talent 1. In J. S. Renzulli, E. J. Gubbins, K. S. McMillen, R. D. Eckert, & C. A. Little (Eds.), Systems and models for developing programs for the gifted and talented (2nd ed., pp. 165–192). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, I., Cáceres, G. R., Rosa, L. D. L. A., & León, P. S. (2021). Analysing educational interventions with gifted students. Systematic review. Children, 8(5), 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geake, J. G., & Gross, M. U. M. (2008). Teachers’ negative affect toward academically gifted students: An evolutionary psychological study. Gifted Child Quarterly, 52(3), 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerven, V. E. (2021). Educational paradigm shifts and the effects on educating gifted students in The Netherlands and Flanders. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 44(2), 171–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilar-Corbi, R., Veas, A., Miñano, P., & Castejón, J.-L. (2019). Differences in personal, familial, social, and school factors between underachieving and non-underachieving gifted secondary students. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gojkov, G., Stojanović, A., & Gojkov-Rajić, A. (2015). Didactic strategies and competencies of gifted students in the digital era. Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal, 5(2), 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffioen, D. M. E., Doppenberg, J. J., & Oostdam, R. J. (2018). Are more able students in higher education less easy to satisfy? Higher Education: The International Journal of Higher Education Research, 75(5), 891–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasch, T., Alvarez, I., & Espasa, A. (2010). University teacher competencies in a virtual teaching/learning environment: Analysis of a teacher training experience. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(2), 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyurko, J., MacCormack, P., Bless, M. M., & Jodl, J. (2016). Why colleges and universities need to invest in quality teaching more than ever: Faculty development, evidence-based teaching practices, and student success. White paper. Association of College and University Educators. Available online: https://acue.org (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Hately, S., & Townend, G. (2020). A qualitative meta-analysis of research into the underachievement of gifted boys. Australasian Journal of Gifted Education, 29(1), 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilbronner, N. N. (2011). Stepping onto the STEM pathway: Factors affecting talented students’ declaration of STEM majors in college. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 34(6), 876–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilbronner, N. N., Connell, E. E., Dobyns, S. M., & Reis, S. M. (2010). The “Stepping Stone Phenomenon”: Exploring the role of positive attrition at an early college entrance program. Journal of Advanced Academics, 21(3), 392–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, K. A. (1991). The nature and development of giftedness: A longitudinal study. Journal for High Ability, 2, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hevel, M. S., Martin, G. L., Weeden, D. D., & Pascarella, E. T. (2015). The effects of fraternity and sorority membership in the fourth year of college: A detrimental or value-added component of undergraduate education? Journal of College Student Development, 56(5), 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinterplattner, S., Wolfensberger, M., & Lavicza, Z. (2022). Honors students’ experiences and coping strategies for waiting time in secondary school and at university. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 45(1), 84–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogeveen, L. (2008). Social emotional consequences of accelerating gifted students [Ph.D. dissertation, Radboud University]. Radboud Repository. Available online: https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/2066/73315/73315_sociemcoo.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Hoogeveen, L. (2022). Talent’s needs: Identification, support, and counseling of talent. Inaugural address. Radboud University. Available online: https://cbo-nijmegen.nl/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Oratie_Lianne_Hoogeveen_lr-2.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Hoogeveen, L., van Hell, J. G., & Verhoeven, L. (2005). Teacher attitudes toward academic acceleration and accelerated students in the Netherlands. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 29(1), 30–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogeveen, L., van Hell, J. G., & Verhoeven, L. (2012). Social-emotional characteristics of gifted accelerated and non-accelerated students in the Netherlands. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(4), 585–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornstra, L., Stroet, K., Eijden, V. E., Goudsblom, J., & Roskamp, C. (2018). Teacher expectation effects on need-supportive teaching, student motivation, and engagement: A self-determination perspective. Educational Research and Evaluation, 24(3–5), 324–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornstra, L., Van Weerdenburg, M., Brand, D. V. M., Hoogeveen, L., & Bakx, A. (2022). High-ability students’ need satisfaction and motivation in pull-out and regular classes: A quantitative and qualitative comparison between settings. Roeper Review, 44(3), 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibragimova, A. N., & Ponomareva, A. A. (2020). Organization of legal education of gifted students using modern methodological tools. International Journal of Higher Education, 9(8), 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C., Gitay, R., Al Hazaa, K., Abdel-Salam, A. S. G., Mohamed, R. I., BenSaid, A., Al-Tameemi, R. A. N., & Romanowski, M. H. (2022). Causes of undergraduate students’ underachievement in a Gulf Cooperation Council Country (GCC) university. SAGE Open, 12(3), 21582440221079847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemier, E., Offringa, J., Eggens, L., & Wolfensberger, M. (2014). Motivatie, leerstrategieën en voorkeur voor doceerbenadering van honoursstudenten in het hbo. Tijdschrift voor Hoger Onderwijs, 31/32(4/1), 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, B., & Kurpius, S. E. R. (2004). Encouraging talented girls in math and science: Effects of a guidance intervention. High Ability Studies, 15(1), 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbrough, E. O., McGee, A. D., & Shigeoka, H. (2022). How do peers impact learning? An experimental investigation of peer-to-peer teaching and ability tracking. Journal of Human Resources, 57(1), 304–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, T., & Gakis, P. (2021). Student teachers’ differentiated teaching practices for high-achieving students. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(7), 916–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakin, J. M., & Wai, J. (2020). Spatially gifted, academically inconvenienced: Spatially talented students experience less academic engagement and more behavioural issues than other talented students. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(4), 1015–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapointe-Antunes, P., & Sainty, B. (2023). Practice makes better: Using immersive cases to improve student performance on day 1 of the common final examination. Accounting Perspectives, 22(4), 485–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrijsen, J., Vansteenkiste, M., Boncquet, M., & Verschueren, K. (2021). Does motivation predict changes in academic achievement beyond intelligence and personality? A multitheoretical perspective. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(4), 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L. E., Rinn, A. N., Crutchfield, K., Ottwein, J. K., Hodges, J., & Mun, R. U. (2021). Perfectionism and the Imposter Phenomenon in academically talented undergraduates. Gifted Child Quarterly, 65(3), 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Liao, Y., Wu, X. A., Mei, X. X., Zeng, Y. H., Wu, J. H., & Ye, Z. J. (2023). Associations between nonrestorative sleep, perceived stress, resilience, and emotional distress in freshmen students: A latent profile analysis and moderated mediation model. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 59(1), 8168838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limeri, L. B., Carter, N. T., Lyra, F., Martin, J., Mastronardo, H., Patel, J., & Dolan, E. L. (2023). Undergraduate lay theories of abilities: Mindset, universality, and brilliance beliefs uniquely predict undergraduate educational outcomes. CBE Life Sciences Education, 22(4), 3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. J. (2014). Questioning the stability of learner anxiety in the ability-grouped foreign language classroom. Asian EFL Journal, 16(3), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C. O., & Feng, L. C. (2020). Teaching higher order thinking skills to gifted students: A meta-analysis. Gifted Education International, 36(2), 196–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubinski, D., Benbow, C. P., Shea, D. L., Eftekhari-Sanjani, H., & Halvorson, M. B. J. (2001). Men and women at promise for scientific excellence: Similarity not dissimilarity. Psychological Science, 12(4), 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunsford, L. G. (2011). Psychology of mentoring: The case of talented college students. Journal of Advanced Academics, 22(3), 474–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma’ajini, O. B. H. (2013). Problems of students of King Abdulaziz University from their own perspectives: A comparative study between average, gifted and students with special needs. Life Science Journal, 10(4), 3762–3778. [Google Scholar]

- Mahenthiran, S., & Rouse, P. J. (2000). The impact of group selection on student performance and satisfaction. International Journal of Educational Management, 14(6), 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mambetalina, A., Nurkeshov, T., Satanov, A., Karkulova, A., & Nurtazanov, E. (2023). Designing a methodological system for the development and support of gifted and motivated students. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1098989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maranges, H. M., Iannuccilli, M., Nieswandt, K., Hlobil, U., & Dunfield, K. (2023). Brilliance beliefs, not mindsets, explain inverse gender gaps in psychology and philosophy. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 89(11–12), 801–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H. W., Martin, A. J., Yeung, A. S., & Craven, R. G. (2016). Competence self-perceptions. In A. J. Elliot, C. S. Dweck, & D. S. Yeager (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation: Theory and application (pp. 85–115). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martindale, A. L., & Hammons, J. O. (2013). Some scholarship students need help, too: Implementation and assessment of a scholarship retention program. Journal of College Student Retention, 14(3), 371–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattheis, J. L. (2018). Importance of transition planning State University Moorhead. Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, M. S. (2006). Gifted students dropping out: Recent findings from a southeastern state. Roeper Review, 28(4), 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendaglio, S. (2013). Gifted students’ transition to university. Gifted Education International, 29(1), 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzon, E. E., Shterts, O. M., & Panfilov, A. N. (2013). Comparative analysis of development of technical giftedness of a person depending on its engagement into specialized educational environment. Middle East Journal of Scientific Research, 16(12), 1686–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mianehsaz, E., Mirhosseini, F., Kashan, F. H., Saharkhan, L., Azadchehr, M. J., Taghadosi, M., Ebrahimzadeh, F., & Zamani-Badi, H. (2022). Talented and gifted mentors for the promotion of motivation, educational, and research activities of nursing students. Strides in Development of Medical Education Journal, 19(1), e1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A. L., & Dumford, A. D. (2018). Do high-achieving students benefit from honors college participation? A look at student engagement for first-year students and seniors. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 41(3), 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A. L., Lambert, A. D., & Neumeister, K. L. S. (2012). Parenting style, perfectionism, and creativity in high-ability and high-achieving young adults. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 35(4), 344–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A. L., Silberstein, S. M., & BrckaLorenz, A. (2021). Teaching honors courses: Perceptions of engagement from the faculty perspective. Journal of Advanced Academics, 32(1), 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A. L., & Smith, V. A. (2017). Exploring differences in creativity across academic majors for high-ability college students. Gifted and Talented International, 32(1), 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C. J., & Bernacki, M. L. (2019). Training preparatory mathematics students to be high ability self-regulators: Comparative and case-study analyses of impact on learning behavior and achievement. High Ability Studies, 30(1), 167–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M. C. (2017). A special program for highly gifted students: The evolution and growth of uni’s honors program University of Northern Iowa. Available online: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/hpt (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Mofield, E., & Parker Peters, M. (2019). Understanding underachievement: Mindset, perfectionism, and achievement attitudes among gifted students. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 42(2), 107–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2010). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. International Journal of Surgery, 8(5), 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhamadiyeva, S., & Hernández-Torrano, D. (2024). Adaptive learning to maximize gifted education: Teacher perceptions, practices, and experiences. Journal of Advanced Academics, 35(4), 652–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narikbaeva, L. M. (2016). University students’ giftedness diagnosis and development. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11(17), 10289–10300. [Google Scholar]

- National Association for Gifted Children. (2013). NAGC—CEC Teacher preparation standards in gifted and talented education. National Association for Gifted Children. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED562612.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Nazarova, O. K., Yarmakeev, I. E., Pimenova, T. S., Abdrafikova, A. R., & Tregubova, T. M. (2018). The role of scientific research work in students’ professional competence formation. Modern Journal of Language Teaching Methods, 8(11), 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Neihart, M., & Yeo, L. S. (2017). Psychological issues unique to the gifted student. In S. I. Pfeiffer, E. Shaunessy-Dedrick, & M. Foley-Nicpon (Eds.), APA handbook of giftedness and talent (pp. 497–510). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeister, K. L. S. (2004). Understanding the relationship between perfectionism and achievement motivation in gifted college students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 48(3), 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nha Hong, Q., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., Rousseau, M.-C., & Vedel, I. (2018). Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 user guide. Available online: https://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Noble, K. D., & Childers, S. A. (2008). A passion for learning: The theory and practice of optima match at the University of Washington. Journal of Advanced Academics, 19(2), 236–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, K. D., Vaughan, R. C., Chan, C., Childers, S., Chow, B., Federow, A., & Hughes, S. (2007). Love and work the legacy of early university entrance. Gifted Child Quarterly, 51(2), 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Conner, M. (2003). Perceptions and experiences of learning at university: What is it like for undergraduates? Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 8(1), 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R. (2006). Exploring a technology-facilitated solution to cater for advanced students in large undergraduate classes. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 22(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oonk, C., Gulikers, J. T. M., den Brok, P. J., Wesselink, R., Beers, P. J., & Mulder, M. (2020). Teachers as brokers: Adding a university-society perspective to higher education teacher competence profiles. Higher Education, 80(4), 701–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, P., & Bigdan, V. (2008). The biggest loser competition. IEEE Transactions on Education, 51(1), 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostermaier, A. (2018). Incentives for students: Effects of certificates and deadlines on student performance. Journal of Business Economics, 88(1), 65–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmiero, M., Palumbo, R., Ceccato, I., La Malva, P., Crosta, A. D., Fusi, G., Crepaldi, M., Rusconi, M. L., & Domenico, A. D. (2023). The role of divergent thinking in interpersonal trust during the COVID-19 pandemic: Creative aspects. Creativity Studies, 16(2), 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, S. P. (2023). College students with high abilities in liberal arts disciplines: Examining the effect of spirituality in bolstering self-regulated learning, affect balance, peer relationships, and well-being. High Ability Studies, 35(1), 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J. D. A., Saklofske, D. H., & Keefer, K. V. (2017). Giftedness and academic success in college and university: Why emotional intelligence matters. Gifted Education International, 33(2), 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patchan, M. M., & Schunn, C. D. (2016). Understanding the effects of receiving peer feedback for text revision: Relations between author and reviewer ability. Journal of Writing Research, 8(2), 227–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, R. S. (2010). Experiences of intellectually gifted students in an egalitarian and inclusive educational system: A survey study. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 33(4), 536–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J. S. (2001). Gifted and at risk: Four longitudinal case studies of post-high-school development. Roeper Review, 24(1), 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P. R., & De Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(1), 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preckel, F., Golle, J., Grabner, R., Jarvin, L., Kozbelt, A., Müllensiefen, D., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., Schneider, W., Subotnik, R., Vock, M., & Worrell, C. F. (2020). Talent development in achievement domains: A psychological framework for within-and cross-domain research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(3), 691–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radulović, B., Stojanović, M., Džinović, M., & Zajkov, O. (2022). Students’ opinion of gifted education and teaching profession. Education and Self Development, 17(1), 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralston, E. S., Compton, J., Forbes, G., Xu, X., & Pontius, J. (2017). I get you: Simple tools for understanding your student populations and their need to succeed. Strategic Enrollment Management Quarterly, 5(3), 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A., Venneman, S., Donche, V., & Verschueren, K. (2022). Factors facilitating and hindering the transition to higher education for high-ability students. Journal of College Student Development, 63(3), 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A., & Verschueren, K. (2019). School careers of high ability students in Flanders. Available online: https://www.projecttalent.be (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Reis, S. M., & McCoach, D. B. (2000). The underachievement of gifted students: What do we know and where do we go? Gifted Child Quarterly, 44(3), 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, S. M., & Renzulli, J. S. (2010). Is there still a need for gifted education? An examination of current research. Learning and Individual Differences, 20(4), 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, S. M., & Renzulli, J. S. (2023). The schoolwide enrichment model: A focus on student strengths & interests. In C. M. Callahan, M. Hertberg-Davis, & M. M. Roberts (Eds.), Systems and models for developing programs for the gifted and talented (pp. 323–352). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, K. G., Leever, B. A., Christopher, J., & Porter, J. D. (2006). Perfectionism, stress, and social (dis)connection: A short-term study of hopelessness, depression, and academic adjustment among honors students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(4), 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M., Abraham, C., & Bond, R. (2012). Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 353–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgley, L. M., DaVia Rubenstein, L., & Callan, G. L. (2020). Gifted underachievement within a self-regulated learning framework: Proposing a task-dependent model to guide early identification and intervention. Psychology in the Schools, 57(9), 1365–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgley, L. M., Rubenstein, L. D., & Callan, G. L. (2022). Are gifted students adapting their self-regulated learning processes when experiencing challenging tasks? Gifted Child Quarterly, 66(1), 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riise, J., Willage, B., & Willen, A. (2022). Can female doctors cure the gender STEMM gap? Evidence from exogenously assigned general practitioners. Review of Economics and Statistics, 104(4), 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinn, A. N., & Boazman, J. (2014). Locus of control, academic self-concept, and academic dishonesty among high ability college students. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 14(4), 88–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinn, A. N., & Plucker, J. A. (2019). High-ability college students and undergraduate honors programs: A systematic review. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 42(3), 187–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchotte, J. A., Matthews, M. S., & Flowers, C. P. (2014). The validity of the achievement-orientation model for gifted middle school students: An exploratory study. Gifted Child Quarterly, 58(3), 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, B. S., Lauver, K., Le, H., Davis, D., Langley, R., & Carlstrom, A. (2004). Do psychosocial and study skill factors predict college outcomes? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 130(2), 261–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, R. W., & Beer, J. S. (2001). Positive illusions about the self: Short-term benefits and long-term costs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(2), 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Nieto, M. C., Sanchez-Gonzalez, A. S., & Sanchez-Miranda, M. P. (2019). How are the gifted? Point of view of university students. Educational Process: International Journal, 8(2), 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruban, L., & Reis, S. M. (2006). Patterns of self-regulatory strategy use among low-achieving and high-achieving university students. Roeper Review, 28(3), 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Gallardo, J. R., & Reavey, D. (2019). Learning science concepts by teaching peers in a cooperative environment: A longitudinal study of preservice teachers. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 28(1), 73–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Moller, A. C. (2017). Competence as central, but not sufficient, for high-quality motivation: A self-determination theory perspective. In A. J. Elliot, C. S. Dweck, & D. S. Yeager (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation: Theory and application (2nd ed., pp. 214–231). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salami, T., Lawson, E., & Metzger, I. W. (2021). The impact of microaggressions on Black college students’ worry about their future employment: The moderating role of social support and academic achievement. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 27(2), 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, S., & Alali, R. (2022). Digital learning tools (institutional-open) and their relationship to educational self-effectiveness and achievement in online learning environments. Przestrzen Spoleczna, 22(3), 226–256. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, A. A. M. S., Abdelsattar, M., Abu Al-Diyar, M., Al-Hwailah, A. H., Derar, E., Al-Hamdan, N. A. H., & Tilwani, S. A. (2022). Altruistic behaviors and cooperation among gifted adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 945766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa Ngiamsunthorn, P. (2020). Promoting creative thinking for gifted students in undergraduate mathematics. Journal of Research and Advances in Mathematics Education, 5(1), 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbaih, A. D. (2023). Creative thinking in students of mathematics in universities and its relationship with some variables. Perspektivy Nauki i Obrazovania, 64(4), 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scager, K., Akkerman, S. F., Pilot, A., & Wubbels, T. (2014). Challenging high-ability students. Studies in Higher Education, 39(4), 659–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, C., & Goebel, V. (2015). Experiences of high-ability high school students: A case study. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 38(4), 428–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuur, J., Van Weerdenburg, M., Hoogeveen, L., & Kroesbergen, E. H. (2021). Social-emotional characteristics and adjustment of accelerated university students: A systematic review. Gifted Child Quarterly, 65(1), 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedykh, T. V., Korshunova, V. V., Velichko, E. V., Sosnovskaia, A. A., Grigorovech, P. N., & Bugaeva, A. A. (2021). Practice-oriented approach to development of leadership competencies of honors students: The project “The territory of intellectual and liberal inventions”. Journal of Siberian Federal University—Humanities and Social Sciences, 14(9), 1331–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeley, K. R. (1984). Perspectives on adolescent giftedness and delinquency. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 8(1), 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J., Biswal, B., Tyagi, P., & Bagai, S. (2023). University-based mentoring program for school going gifted students. Gifted and Talented International, 39(1), 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J., Lee, H. J., Park, H., Hong, Y., Song, Y. K., Yoon, D. U., & Oh, S. (2023). Perfectionism, test anxiety, and neuroticism determines high academic performance: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegle, D. (2018). Understanding underachievement. In S. I. Pfeiffer (Ed.), Handbook of giftedness in children (pp. 285–297). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegle, D., Da Via Rubenstein, L., Pollard, E., & Romey, E. (2010). Exploring the relationship of college freshmen honors students’ effort and ability attribution, interest, and implicit theory of intelligence with perceived ability. Gifted Child Quarterly, 54(2), 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegle, D., Rubenstein, L. D., & Mitchell, M. S. (2014). Honors students’ perceptions of their high school experiences: The influence of teachers on student motivation. Gifted Child Quarterly, 58(1), 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, M. D. V., Cuervo, A. A. V., Amezaga, T. R. W., Sanchez, A. C. R., Guzman, R. Z., & Agraz, J. P. N. (2015). Differences in achievement motivation and academic and social self-concept in gifted students of higher education. Journal of Curriculum and Teaching, 4(1), 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, P. J. (2018). NYC selective specialized public high schools and honors college STEM degrees: A previously unexplored relationship. Journal of Advanced Academics, 29(4), 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. S. (2006). Examining the long-term impact of achievement loss during the transition to high school. Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 17(4), 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, K. E., & Adelson, J. L. (2017). The development and validation of the perceived academic underachievement scale. Journal of Experimental Education, 85(4), 614–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, K. E., Malin, J. L., Dent, A. L., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2014). The message matters: The role of implicit beliefs about giftedness and failure experiences in academic self-handicapping. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(1), 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenbergen-Hu, S., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Calvert, E. (2020). The effectiveness of current interventions to reverse the underachievement of gifted students: Findings of a meta-analysis and systematic review. Gifted Child Quarterly, 64(2), 132–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayhorn, T. L. (2009). The burden of proof: A quantitative study of high-achieving Black collegians. Journal of African American Studies, 13(4), 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subotnik, R. F., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Worrell, F. C. (2011). Rethinking giftedness and gifted education: A proposed direction forward based on psychological science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, Supplement, 12(1), 3–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W. K., Sunar, M. S., & Goh, E. S. (2023). Analysis of the college underachievers? Transformation via gamified learning experience. Entertainment Computing, 44, 100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiemann, P. (2022). The persistent effects of short-term peer groups on performance: Evidence from a natural experiment in higher education. Management Science, 68(2), 1131–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, P., & Jaque, S. V. (2016). Overexcitability and optimal flow in talented dancers, singers, and athletes. Roeper Review, 38(1), 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindage, M. F., Lemus, D., & Stohl, C. (2024). Understanding the perceptions of memorable messages about academic performance among students of color in the United States. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 52(2), 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, C. A. (2001). How to differentiate instruction in mixed-ability classrooms. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, K.-F., & Fu, G. (2016). Underachievement in gifted students: A case study of three college physics students in Taiwan. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 4(4), 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tushnova, A. Y. (2020). Features of social-perceptual properties of mathematically gifted students. International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education, 8(1), 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyurikov, A. G., Kunizheva, D. A., Voevodina, E. V., & Gruzina, Y. M. (2022). The impact of the university environment on the development of student research potential: Implementing inbreeding in an open innovation environment. Higher Education Quarterly, 76(4), 874–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Muijsenberg, E., Ramos, A., Vanhoudt, J., & Verschueren, K. (2021). Gifted university students: Development and evaluation of a counseling program. Journal of College Counseling, 24(3), 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Zanden, P. J., Denessen, E., Cillessen, A. H., & Meijer, P. C. (2019). Patterns of success: First-year student success in multiple domains. Studies in Higher Education, 44(11), 2081–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanTassel-Baska, J., & Brown, F. E. (2007). Toward best practice: An analysis of the efficacy of curriculum models in gifted education. Gifted Child Quarterly, 51(4), 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelaar, B., & Hoogeveen, L. (2020). Hoogbegaafdheid meten … Waarom zou je? Kind en Adolescent, 41(1), 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, J., Lubinski, D., & Benbow, C. P. (2005). Creativity and occupational accomplishments among intellectually precocious youths: An age 13 to age 33 longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(3), 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkington, C., & Bernacki, M. L. (2020). Appraising research on personalized learning: Definitions, theoretical alignment, advancements, and future directions. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 52(3), 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watters, J. J. (2010). Career decision making among gifted students: The mediation of teachers. Gifted Child Quarterly, 54(3), 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, K. R. (2020). The social and emotional world of gifted students: Moving beyond the label. Psychology in the Schools, 57(10), 1528–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissink, K. (2024). Hoogbegaafd op de universiteit: Sociaal-emotionele en onderwijsbehoeften van studenten met kenmerken van hoogbegaafdheid [Unpublished Master’s thesis, Radboud University]. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfensberger, M. V. C. (2015). Talent development in European higher education: Honors programs in the Benelux, Nordic and German-speaking countries. SpringerOpen. Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-12919-8.

- Woody, R. H., & Parker, E. C. (2012). Encouraging participatory musicianship among university students. Research Studies in Music Education, 34(2), 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Assouline, S., McClurg, V. M., & McCallum, R. S. (2022). An investigation of an early college entrance program’s ability to impact intellectual and social development. Roeper Review, 44(2), 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusmansyah, Y., Utaminingsih, D., Rosra, M., Andriyanto, R. E., Maharani, C. A., & Nurulsari, N. (2019). The working framework of religious counseling services to strengthen undergraduate gifted student’s mental ability: As a powerful alternative strategy for achieving academic success. Journal for the Education of Gifted Young Scientists, 7(2), 273–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A., Chandler, K. L., Vialle, W., & Stoeger, H. (2017). Exogenous and endogenous learning resources in the actiotope model of giftedness and its significance for gifted education. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 40(4), 310–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A., Debatin, T., & Stoeger, H. (2019). Learning resources and talent development from a systemic point of view. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1445(1), 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(2), 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J., Schunk, D. H., & Dibenedetto, M. K. (2017). The role of self-efficacy and related beliefs in self-regulation of learning and performance. In A. J. Elliot, C. S. Dweck, & D. S. Yeager (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation: Theory and application (2nd ed., pp. 313–333). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

| Authors | Country | Research Institution | Study Design | Sample Size | Instruments | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afshar and Movassagh (2017) | Iran | A public university | Survey | 76 | California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST), Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL) | Critical thinking and strategy use had a significant positive correlation with university achievement, with critical thinking being stronger and an asset to the high-achieving group. |

| Afshari et al. (2020) | Iran | A public university | Mixed method | ncontrol = 30 nexperimental = 30 | Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL), International English Language Testing System (IELTS) | Group dynamic assessment was more effective than conventional explicit intervention for supporting EFL writing development, and it worked best for low-ability learners. In addition, this intervention promoted both EFL writing and learner self-regulation. |

| Al-Khayat et al. (2017) | Jordan | A public college | Survey | 66 | Questionnaire developed by the authors | The highest teaching strategies preferred by gifted students were related to the creative thinking dimension followed by critical thinking strategies and accommodations for individual differences, with the lowest being presentations. |

| Al-Qahtani (2021) | Saudi Arabia | A non-specified university | Survey | 92 | Test of English as Foreign Language (TOEFL), Survey of Reading Strategies (SORS) | Each ability level reported strategy was used differently in terms of order and intensity. There was also a statistical significance in strategy use between the high ability and the low ability levels. The low ability-level participants reported higher use of the global reading strategies than the high-ability group. |

| Al-Shabatat et al. (2010) | Malaysia | A non-specified university | Survey | 180 | Cattell Culture Fair Test (CCFT) | Achievement motivation and fluid intelligence significantly influenced intellectual giftedness, with strong direct and indirect effects. Motivation factors like self-confidence, perseverance, and autonomy enhanced cognitive growth, supporting the development of giftedness. |

| Al-Ta’ani and Hamadneh (2023) | Jordan | A private university | Survey | 86 | Questionnaire developed by the authors | Active learning strategies enhanced students’ motivation and encouraged faculty to foster and stimulate students’ enthusiasm for learning. |

| Ali et al. (2021) | Pakistan | A public university | Survey | 180 | Self-Report Measure of Emotional Intelligence (SRMEI) | Male students exhibited higher emotional intelligence than female students, particularly in the areas of emotional self-regulation and emotional self-awareness. However, no significant gender difference was found in interpersonal skills. |

| Almousa et al. (2022) | Jordan | A public and a private university | Survey | 353 | Questionnaire developed by the authors | Academic challenges were the biggest concern for high-achieving students, while family issues had minimal impact. Bachelor’s students struggled more than advanced-level students, suggesting a need for early academic support. Females experienced more emotional distress, highlighting the need for mental health interventions. STEM students faced more study-related issues, requiring targeted academic support. |

| Almukhambetova and Hernandez-Torrano (2021) | Kazakhstan | Two universities | Mixed method | 201 | Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire (SACQ) | The adjustment of gifted students to university was found to be a complex process, requiring a comprehensive consideration of freshmen experiences when examining their transition to post-secondary education. |

| Andrews et al. (2020) | US | Diverse institutions | Survey | >1,000,000 | Data analysis | Longhorn opportunity scholars’ program had large, positive effects on enrolment in and graduation from UT-Austin, master’s degree enrolment, and earnings. |

| Ashtiyani et al. (2013) | Iran | A public university | Survey | ncontrol = 180 nexperimental = 56 | Questionnaire developed by the authors | The mean score of educational, research, and psycho-spiritual problems between gifted and ordinary students differed significantly (p > 0.05). The multivariate regression model predicted 52.8 of the total variances of the gifted students’ problems. |

| Avsec and Savec (2021) | Slovenia | A public university | Survey | 225 | Questionnaire developed by the authors | Enhancing the transformative aspect of education for sustainable development in pre-service teachers required critical reflection, self-awareness, risk-taking, a holistic perspective, openness to diversity, and social support. Additionally, self-directed learning played a moderating role in transformative learning among pre-service science teachers. |

| Bain et al. (2006) | US | Not specified | Survey | 285 | Questionnaire developed by the authors | Identified misconceptions about homogeneity, synchronous development, and emotional/social distress in gifted children and their non-gifted siblings. |

| Bain et al. (2010) | US | A public university | Survey | 88 | Foreign Language Attitudes and Perceptions Survey-College (FLAPS-C), Modern Language Aptitude Test (MLAT), College Academic Attribution Scale- Foreign Language (CAAS-FL) | Gifted students scored higher in aptitude and had a more positive attitude toward learning a foreign language, but both groups showed no differences in success attributions. |

| Barth et al. (2018) | US | A non-specified college | Survey | 526 | Questionnaire developed by the authors | Students held stereotypical ability beliefs of others but showed no gender differences in STEM self-efficacy or career interests. |

| Baslanti and McCoach (2006) | Turkey | A public university | Survey | 165 | School Attitude Assessment Survey-Revised (SAAS-R) | Five key factors of underachievement were identified: academic self-perceptions, attitudes toward teachers, attitudes toward school, goal valuation, and motivation/self-regulation with motivation/self-regulation as the strongest predictor. |

| Bauer et al. (2023) | Germany | Diverse institutions | Mixed method | 3584 | Questionnaire developed by the authors | First-generation students perceived themselves as less talented but equally diligent, which impacted their academic experience and engagement. This self-concept bias was strongest in talent-focused environments but lessened when effort was emphasized. |

| Beduna and Perrone-McGovern (2016) | US | A public university | Survey | 144 | Overexcitabilities Questionnaire II (OEQII), Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS), Brief Emotional Intelligence Scale (BEIS-10) | Emotional and intellectual overexcitability were positively linked to emotional intelligence, which in turn was positively associated with subjective well-being. Path analysis confirmed that emotional intelligence mediated the relationship between overexcitability and well-being. |

| Bell and McCallum (2012) | US | A non-specified university | Survey | 95 | Modern Language Aptitude Test (MLAT), Questionnaire developed by the authors, Foreign Language Attribution Scale (FLAS), Foreign Language Attitudes and Perceptions Survey (FLAPS) | Modern language aptitude test part IV and luck attributions significantly predicted exam grades within a multiple regression analysis. In a second multiple regression analysis, only effort and ability attributions significantly predicted anxiety. |

| Ben-Eliyahu (2019) | US | A non-specified university | Mixed method | 271 | Questionnaire developed by the authors, Patterns of Adaptive Learning Scales (PALS), Academic Focusing Scale (AFS), Self-Control scale, Social Achievement Goals Scale, Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) | Gifted students exhibited diverse self-regulated learning (SRL) profiles, with three groups: highly regulated, regulated, and behaviorally dysregulated. Typical students most resembled the regulated group. Behaviorally dysregulated gifted students had lower academic and social SRL but showed no differences in trait emotion regulation or self-control, suggesting a situated SRL effect. Gifted students also showed stronger links between motivation and SRL, with mastery goal orientation predicting all SRL forms only for them. |

| Bennett (2009) | UK | A non-specified university | Survey | 511 | Questionnaire developed by the authors | Three major facets of academic self-concept were found to be particularly relevant: self-belief in one’s academic competence, self-appreciation of one’s personal worth as a student, and self-connection with being an undergraduate. |

| Bergold et al. (2021) | Germany | Not specified | Survey | ncontrol = 87 nexperimental = 345 | Experiment designed by the authors | Stereotypical representations in the media about intellectually gifted individuals contributed to the stigmatization of gifted individuals. Nonstereotyped, evidence-based representations caused more positive attitudes. |

| Boazman and Sayler (2011) | UK | A public university | Survey | 157 | General Perceived Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE), Questionnaire developed by the authors, Personal Well-being Index-Adult (PWI-A), State Trait Cheerfulness Inventory (STCI-T) | Early college entrants expressed greater global satisfaction with their lives than older peers. They reported elevated levels of satisfaction in their achievements, immediate standard of living, personal safety, and future security than age peers. They expressed powerful feelings of general self-efficacy and high levels of trait seriousness, which are two constructs related to facilitating success. |

| A. Campbell (2019) | South Africa | A public university | Mixed method | 265 | Mindset Assessment Profile Tool | Without experiencing interventions aimed at developing growth mindset, students showed small shifts towards stronger growth mindsets over their first year. |

| K. C. Campbell and Fuqua (2008) | US | A public university | Survey | 336 | Attitude toward Ability Grouping Questionnaire | The most important discriminating variables predicting student completion were high school GPA, high school class rank, first semester college GPA, gender, and initial housing assignment (honors housing or other). |

| Canaan et al. (2022) | Lebanon | A private university | Survey | 3857 | Data analysis | Higher adviser value-added significantly improved freshmen GPA, time to completion, and four-year graduation rates. Additionally, it increased the likelihood of high-ability students enrolling in and graduating with a STEM degree. |

| Caplan et al. (2002) | US | A public college | Survey | 162 | Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire (SACQ), Self-Report Measure of Emotional Intelligence (SRMEI), Overexcitabilities Questionnaire II (OEQII) | Measures of student self-concept and family environment provided valuable performance and adjustment insights for early entrance programs. Identifying at-risk students and families could help with academic and retention challenges, while programs supporting emotional growth and personal adjustment could benefit all admitted students. |

| Clark et al. (2018) | US | A non-specified university | Survey | 393 | Transition to College Inventory (TCI) | Honors college students achieved high grades and retention rates, with self-confidence and external influences on college choice as key non-cognitive predictors of these outcomes. |

| Clasen (2006) | US | A public university | Mixed method | 158 | Questionnaire developed by the authors and interviews | The findings supported the value of multiple identification methods, including problem-solving, teacher-identified leadership, and GPA. Additionally, a long-term university/school partnership program for underrepresented gifted students showed that higher student involvement correlated with better academic outcomes. |

| Conejeros-Solar and Gómez-Arízaga (2015) | Chile | A semi-public university | Mixed method | 254 | Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire (SACQ), Questionnaire developed by the authors | Gifted students showed stronger academic development and faculty relationships in college. However, they struggled with time management, weak study habits, and gaps in content knowledge due to poor high school academic preparation. |

| Cross et al. (2018) | US | A non-specified university | Survey | 410 | Questionnaire, Big Five Inventory (BFI), Adult Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (ASIQ) | High perfectionism and suicidal ideation were risk factors in two student profiles (possible misfits and serious students), suggesting a need for enhanced psychological support. The largest group (typical friendly) had above-norm extraversion, while all other profiles had below-norm introversion. Neuroticism was higher than the norm in introverted profiles. |

| Deibl and Zumbach (2023) | Austria | A non-specified university | Survey | 156 | Myths and Facts Questionnaire, SESSKO Questionnaire | Results showed no significant difference between freshmen and advanced students in identifying myths, but freshmen identified slightly more facts correctly. Self-confidence was crucial, as master’s students with high self-confidence identified more facts correctly. |

| Derado et al. (2016) | US | A public university | Survey | 976 | Point Reward System (PRS), Traditional assessment method, Student Impact Index (SII) | The study found that the Point Reward System significantly lowered withdrawal, failure, and dropout rates, improved student engagement, and had a greater impact on learning compared to traditional assessment methods in college mathematics classrooms. |

| Domínguez-Soto et al. (2023) | Spain | A non-specified university | Survey | 584 | Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ), Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale (CIPS), Harvey Impostor Scale, Perceived Fraudulence Scale, Leary Impostor Scale, IPP-31 | The CIPS demonstrated strong reliability (α = 0.826), supporting its sensitivity and reliability in measuring impostor syndrome. The MLQ was reported as well-established, with previous research indicating acceptable reliability in European samples (ranging from 0.61 to 0.78). However, in this study, some factors had lower reliability (as low as 0.47), which led the researchers to simplify the model to three leadership factors. |

| Eddy et al. (2013) | US | A public university | Survey | 817 | Experiment designed by the authors | Students who built their own phylogenetic trees performed significantly better in assessments than those who analyzed existing trees. Undergraduate students who completed a tree building activity scored similarly to Biology PhD students, suggesting its effectiveness in teaching tree-thinking. |

| Eiselen and Geyser (2003) | South Africa | A public university | Mixed method | 45 | Questionnaire developed by the authors, Brown Holzman Survey of Study Habits and Attitudes (SSHA C), General Scholastic Aptitude Test (GSAT) | Achievers demonstrated better communication skills, diligence, and cognitive abilities than at-risk students, earning higher school marks. Additionally, their perceptions of success and failure differed significantly from those of at-risk students. |

| Ellala et al. (2022) | United Arab Emirates | Not specified universities | Survey | 388 | Questionnaire developed by the authors | Among UAE students, enthusiasm and agility positively correlated with linguistic ability. For gifted students, institutional support significantly enhanced attention, skill, and linguistic intelligence. |

| Elsamanoudy and Abdelaziz (2020) | United Arab Emirates | A private university | Survey | 130 | Questionnaire developed by the authors | The study found that 66% of interior design students joined due to passion, and 95% effectively learned project requirements. Teaching strategies had a significant positive impact on third-year students. The study concluded that creative and critical thinking strategies should replace conventional methods like memorization to help gifted students reach equal motivation levels as their peers. |

| Erdogan (2017) | Turkey | A public university | Survey | 82 | Science Teaching Attitude Scale, Scientific Attitude Inventory (SAI II) | A significant grade-level difference and a strong correlation between scientific attitudes and science teaching attitudes was found. It recommends creating learning environments that positively influence both attitudes. |

| Fong and Krause (2014) | US | A public university | Mixed method | 49 | Nelson–Denny Reading Test (NDRT) | Underachievers had significantly less mastery experiences and verbal persuasions despite having similar levels of self-efficacy. |

| Gojkov et al. (2015) | Serbia | A public research university | Survey | 112 | Questionnaire developed by the authors Didactic strategies and competencies of gifted students (DSCGS-1) | The highest-achieved competencies were crucial for intellectual functioning but not directly linked to critical thinking, intellectual autonomy, or deep conceptual understanding. They were more related to basic knowledge, factual understanding, and event explanations. |

| Griffioen et al. (2018) | The Netherlands | A public college | Survey | 733 | Questionnaire developed by the authors | Cognitively abler students were less satisfied in vocational education, feeling insufficiently challenged cognitively and creatively and harder to satisfy. |

| Heilbronner (2011) | US | Not specified | Survey | 360 | Questionnaire developed by the authors The Pathways Survey | Key predictors of choosing a STEM major in college were self-belief in STEM ability and the quality of academic experiences, including challenge level, hands-on learning, and career preparation adequacy. |

| Heilbronner et al. (2010) | US | A private university | Mixed method | 43 | Questionnaire developed by the authors PEG Alumnae Survey | Students who left an early college acceleration program often sought greater academic challenges or specialized majors, supporting the idea of positive attrition. |

| Hevel et al. (2015) | US | Diverse institutions | Survey | 2212 | Secondary data analysis, Critical Thinking Test (CTT), National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE), WNS Student Experiences Survey, Defining Issues Test 2 (DIT2), Need for Cognition Scale (NCS), Positive Attitude Toward Literacy Scale (PATLS), Ryff Scales of Psychological Well-Being (RPWB) | The study found no direct effect of fraternity/sorority membership on educational outcomes in the fourth year of college. However, it identified five conditional effects related to students’ academic abilities and racial/ethnic identities. Fraternity/sorority membership negatively affected critical thinking in White students but had no effect on students of color. It was also associated with lower moral reasoning in students of color but higher in White students. Additionally, students with lower pre-college critical thinking skills experienced negative effects on critical thinking, while those with higher pre-college need for cognition showed growth. |

| Hoogeveen et al. (2012) | The Netherlands | A public research university | Survey | 203 | Questionnaire developed by the authors (incl. Self-Description Questionnaire SDQ) and observation | The study found minimal social–emotional differences between accelerated and non-accelerated gifted students, with small advantages for accelerated students. Multiple grade skipping had no negative effects, and long-term outcomes of acceleration were positive. Personal and environmental factors only impacted non-accelerated students. |

| Ibragimova and Ponomareva (2020) | Russia | A public research university | Survey | 166 | Questionnaire developed by the authors | Modern methodological tools and digital platforms played a crucial role in enhancing legal education for gifted students. Future law teachers’ pedagogical competencies were essential for effectively utilizing these tools, and digitalization improved educational environments for gifted students. |

| Kerr and Kurpius (2004) | US | Not specified | Survey | 502 | Vocational Preference Inventory (VPI), Adolescent At-Risk Behaviors Inventory (AARBI), Career Behaviors Inventory (CBI), Educational Self-Efficacy-Adolescence Scale (ESEA), Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) | Self-esteem, school self-efficacy, and future self-efficacy increased from pre-test to follow-up. Girls showed greater career exploration and were more likely to persist in nontraditional career choices. |

| Kokkinos and Gakis (2021) | Greece | A public university | Mixed method | 142 | Questionnaire developed by the authors and observations | Participants primarily differentiated teaching based on students’ learning readiness but provided less support for high-achievers, mainly by offering more difficult tasks and higher-order thinking activities. They believed their strategies mainly influenced students’ cognitive learning. |

| Lakin and Wai (2020) | US | Diverse institutions | Survey | 506,984 | Secondary data analysis | Spatially talented students faced greater academic challenges, including reading difficulties, poor study habits, and behavioral issues, and were less likely to complete college degrees than other talented students. |

| Lapointe-Antunes and Sainty (2023) | US | A public research university | Mixed method | 360 | Secondary data analysis Questionnaire developed by the authors | An immersive case improved student practice performance but not specifically for high-ability students. Extensive six-to-eight-week exam preparation helped close performance gaps among students. |

| Lee et al. (2021) | US | A non-specified university | Survey | 244 | Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale (CIPS), Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS) | Socially prescribed perfectionism and honors program participation were associated with higher imposter feelings in undergraduate students. |

| Li et al. (2023) | China | Two universities | Survey | 818 | Questionnaire, Nonrestorative Sleep Scale (NRSS), Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10), Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) | Freshmen students exhibited heterogeneity in perceived stress, which mediated the link between nonrestorative sleep and emotional distress. However, resilience did not significantly moderate these relationships. |

| Limeri et al. (2023) | US | Diverse institutions | Survey | 1194 | Undergraduate Lay Theories of Abilities Survey (ULTrA) | Mindset, brilliance, and universality were distinct and empirically discriminable constructs rather than aspects of the same belief. Using the Undergraduate Lay Theories of Abilities survey, factor analyses, and Structural Equation Models showed that each belief uniquely influenced psychosocial and academic outcomes. |

| Liu (2014) | Taiwan | A non-specified university | Survey | 143 | Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS), Attitude toward Ability Grouping Questionnaire | High-achieving students experienced higher anxiety in English classes, particularly through tension in class, nervousness when speaking, and fear of being laughed at. Students generally favored ability grouping, believing it benefited their language learning. |

| Lubinski et al. (2001) | US | Diverse institutions | Survey | 1470 | Scholastic Assessment Test (SAT), Study of Values (SOV), Strong Vocational Interest Inventory (SVII) | World-class U.S. math–science graduate students exhibited exceptional quantitative reasoning, strong scientific interests, and persistence in scientific skill development from adolescence. They were identifiable early based on non-intellectual attributes, aligning with profiles of distinguished scientists. Sex differences were minimal among graduate students but present in the comparison group. Developing scientific expertise required similar educational experiences for both sexes. |