Psychosocial Factors Influencing Resilience in a Sample of Victims of Armed Conflict in Colombia: A Quantitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Measures

2.3. Mental Health Assessment

2.3.1. Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC 10)

2.3.2. Brief Resilience Coping Scale (BRCS)

2.3.3. The APGAR Family Scale

2.3.4. AUDIT-C Questionnaire

2.3.5. Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) and Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2)

2.3.6. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)-8

2.3.7. Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.1.1. Sociodemographic Descriptive Data

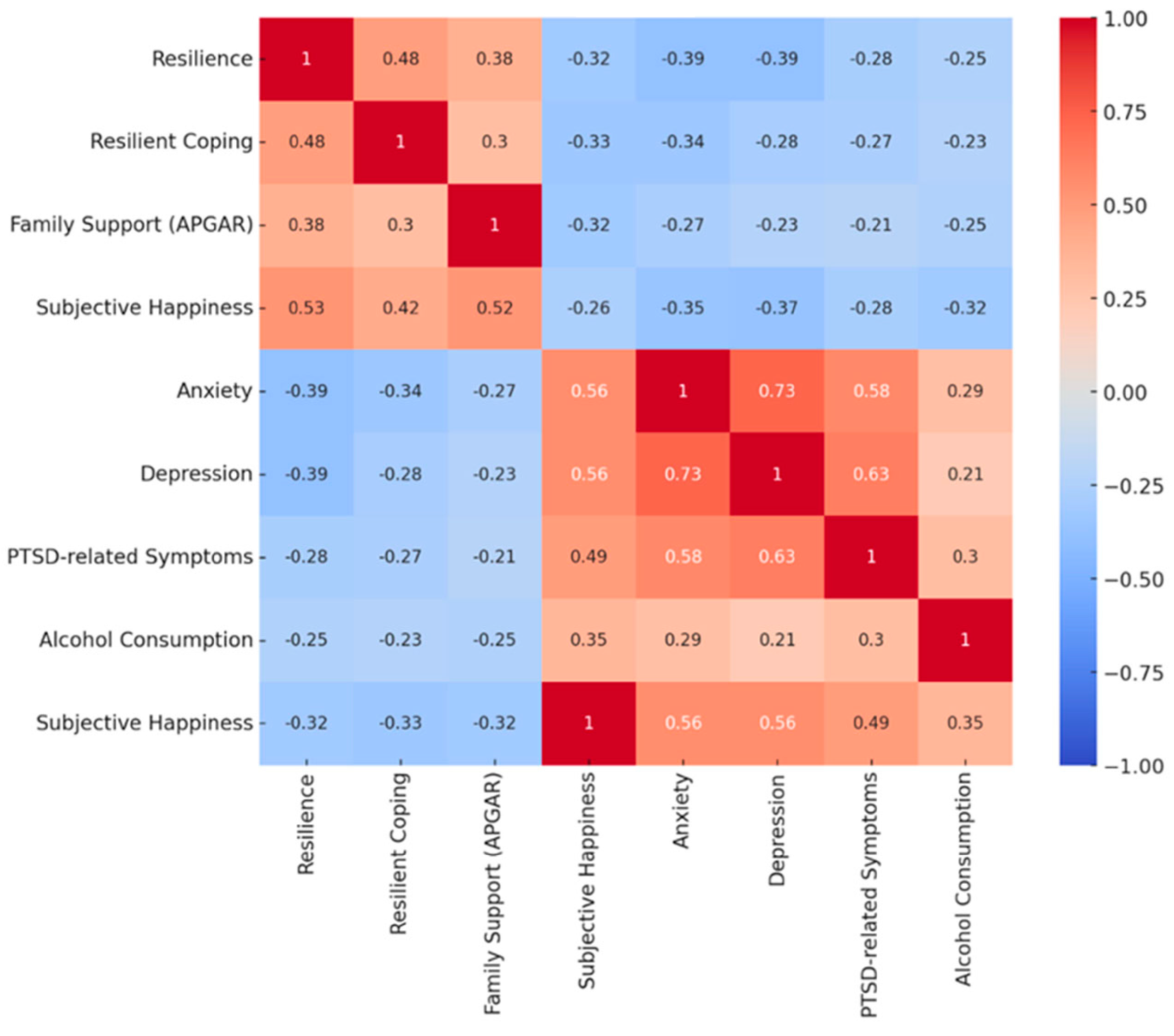

3.1.2. Bivariate Analysis

3.1.3. Factors Related to Armed Conflict Exposure

3.2. Normality Tests

3.3. Group Differences (Resilient vs. Non-Resilient Individuals)

3.4. Multivariate Analysis (MANOVA)

3.5. Predictive Models of Resilience

Interpretation of Odds Ratios, Model Fit, and Predictive Ability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, R. E., & Boscarino, J. A. (2006). Predictors of PTSD and delayed PTSD after disaster: The impact of exposure and psychosocial resources. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194(7), 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldwin, C. M. (2009). Stress, coping, and development: An integrative perspective. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, T. E., Hansen, M., Ravn, S. L., Seehuus, R., Nielsen, M., & Vaegter, H. B. (2018). Validation of the PTSD-8 scale in chronic pain patients. Pain Medicine, 19(7), 1365–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, L. (1994). El APGAR familiar en el cuidado primario de salud. Colombia Médica, 25(1), 26–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babor, T. F., Higgins-Biddle, J. C., Saunders, J. B., & Monteiro, M. G. (2001). Cuestionario de Identificación de los Trastornos debidos al Consumo de Alcohol (AUDIT). Organización Mundial de la Salud.

- Bakic, H., & Ajdukovic, D. (2019). Stability and change post-disaster: Dynamic relations between individual, interpersonal, and community resources and psychosocial functioning. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1614821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, V., Méndez, F., Martínez, C., Palma, P. P., & Bosch, M. (2012). Characteristics of the Colombian armed conflict and the mental health of civilians living in active conflict zones. Conflict and Health, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benight, C. C., & Bandura, A. (2004). Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Behavior Research and Therapy, 42(10), 1129–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, J., Rahill, G. J., Laconi, S., & Mouchenik, Y. (2016). Religious beliefs, PTSD, depression and resilience in survivors of the 2010 Haiti earthquake. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist, 59(1), 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G. A., & Westphal, M. (2024). The three axioms of resilience. Journal of Trauma and Stress, 37(5), 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Escobar, F. J., Osorio-Cuéllar, G. V., Pacichana-Quinayaz, S. G., Rangel-Gómez, A. N., Gomes-Pereira, L. D., Fandiño-Losada, A., & Gutiérrez-Martínez, M. I. (2021). Impacts of violence on the mental health of afro-descendant survivors in Colombia. Medicine, Conflict and Survival, 37, 124–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, C., Lorenzo-Seva, U., Ferrando, P. J., Sorribes, E., Rodríguez-González, A., Obispo, B. M., & Jiménez-Fonseca, P. (2022). Measurement properties of the Spanish version of the brief resilient coping scale (BRCS) in cancer patients. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 22(3), 100313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camargo, A., Olmos, J., Higuera-Dagovett, E., Vargas, R., & Barreto, R. (2019). Papel de los profesionales de la salud en el diseño, obtención y entendimiento del consentimiento informado: Una revisión. Revista U.D.C.A Actualidad & Divulgación Científica, 22(2), e1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Sills, L., & Stein, M. B. (2007). Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(6), 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosco, T. D., Howse, K., & Brayne, C. (2017). Healthy ageing, resilience and wellbeing. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 26(6), 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusack, S. E., Wright, A. W., & Amstadter, A. B. (2023). Resilience and alcohol use in adulthood in the United States: A scoping review. Preventive Medicine, 168, 107442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Cárdenas, S., Tirado-Amador, L., & Simancas-Pallares, M. (2017). Validez de constructo y confiabilidad de la APGAR familiar en pacientes odontológicos adultos de Cartagena, Colombia. Revista Universidad Industrial de Santander Salud, 49(4), 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errazuriz, A., Beltrán, R., Torres, R., & Passi-Solar, A. (2022). The validity and reliability of the PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 on screening for major depression in Spanish-speaking immigrants in Chile: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 13975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extremera, N., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2014). The Subjective happiness scale: Translation and preliminary psychometric evaluation of a Spanish version. Social Indicators Research, 119(1), 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, W., & Steel, Z. (2023). The impact of immigration detention on the mental health of refugees and asylum seekers. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 36(3), 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Restrepo, C., Sarmiento-Suárez, M. J., Alba-Saavedra, M., Calvo-Valderrama, M. G., Rincón-Rodríguez, C. J., González-Ballesteros, L. M., & van Loggerenberg, F. (2023). Mental health problems and resilience in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic in a post-armed conflict area in Colombia. Scientific Reports, 13, 9743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Restrepo, C., Tamayo-Martínez, N., Buitrago, G., Guarnizo-Herreño, C. C., Garzón-Orjuela, N., Eslava-Schmalbach, J., & Rincón, C. J. (2016). Violencia por conflicto armado y prevalencias de trastornos del afecto, ansiedad y problemas mentales en la población adulta colombiana. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría, 45(2), 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M., Andersen, T. E., Armour, C., Elklit, A., Palic, S., & Mackrill, T. (2010). PTSD-8: A short PTSD inventory. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 6, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera-Moreno, D., Carvajal-Ovalle, D., Cueva-Nuñez, M. A., Acevedo, C., Riveros-Munévar, F., Camacho, K., Fajardo-Tejada, D. M., Clavijo-Moreno, M. N., Lara-Correa, D. L., & Vinaccia-Alpi, S. (2018). Body image, perceived stress, and resilience in military amputees of the internal armed conflict in Colombia. International Journal of Psychology Research (Medellín), 11(2), 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2003). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limonero, J. T., Tomás-Sábado, J., Gómez-Romero, M. J., Maté-Méndez, J., Sinclair, V. G., Wallston, K. A., & Gómez-Benito, J. (2014). Evidence for validity of the brief resilient coping scale in a young Spanish sample. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 17, E34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löwe, B., Kroenke, K., & Gräfe, K. (2005). Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2). Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58(2), 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46(2), 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A. S. (2014). Global perspectives on resilience in children and youth. Child Development, 85(4), 1244–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, E. C., Kotte, A., Kimbrel, N. A., DeBeer, B. B., Elliott, T. R., Gulliver, S. B., & Morissette, S. B. (2019). Predictors of lower-than-expected posttraumatic symptom severity in war veterans: The influence of personality, self-reported trait resilience, and psychological flexibility. Behavior Research and Therapy, 113, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Suchet, L., Camargo, N., Sangraula, M., Castellar, D., Diaz, J., Meriño, V., Chamorro Coneo, A. M., Chávez, D., Venegas, M., Cristobal, M., Bonz, A. G., Ramirez, C., Trejos Herrera, A. M., Ventevogel, P., Brown, A. D., Schojan, M., & Greene, M. C. (2024). Comparing mediators and moderators of mental health outcomes from the implementation of Group Problem Management Plus (PM+) among Venezuelan refugees and migrants and Colombian returnees in Northern Colombia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(5), 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, B., Kim, J. Y., DeVylder, J. E., & Song, A. (2016). Family functioning, resilience, and depression among North Korean refugees. Psychiatry Research, 245, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, B., & Andersen, K. (2022). Alkohol, angst og depression. Ugeskrift for Læger, 184, V10210816. [Google Scholar]

- Notario-Pacheco, B., Martínez-Vizcaíno, V., Trillo-Calvo, E., Pérez-Yus, M. C., Serrano-Parra, D., & García-Campayo, J. (2014). Validity and reliability of the Spanish version of the 10-item Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC-10) in patients with fibromyalgia. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuwayhid, I., Zurayk, H., Yamout, R., & Cortas, C. S. (2011). Summer 2006 war on Lebanon: A lesson in community resilience. Global Public Health, 6(5), 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oviedo, L., Seryczyńska, B., Torralba, J., Roszak, P., Del Angel, J., Vyshynska, O., & Churpita, S. (2022). Coping and resilience strategies among Ukraine war refugees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özmete, E., & Pak, M. (2023). Family functioning and community resilience during the COVID-19 lockdown period in Turkey. Social Work in Public Health, 38(5–8), 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, M., Sánchez, F., & Blanco, A. (2021). Effects of a community resilience intervention program on victims of forced displacement: A case study. Journal of Community Psychology, 49(6), 1630–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, F., Manea, L., Trepel, D., & McMillan, D. (2016). Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 39, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purgato, M., Tedeschi, F., Bonetto, C., de Jong, J., Jordans, M. J., Tol, W. A., & Barbui, C. (2020). Trajectories of psychological symptoms and resilience in conflict-affected children in low-and middle-income countries. Clinical Psychology Review, 82, 101935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, M. T., & Padilla-Medina, D. (2023). Armed conflict exposure and mental health: Examining the role of imperceptible violence. Medicine, Conflict and Survival, 39, 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saghin, D., Lupchian, M. M., & Lucheș, D. (2022). Social cohesion and community resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic in northern Romania. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheffer, M., Bockting, C. L., Borsboom, D., Cools, R., Delecroix, C., Hartmann, J. A., Kendler, K. S., van de Leemput, I., van der Maas, H. L. J., van Nes, E., Mattson, M., McGorry, P. D., & Nelson, B. (2024). A dynamical systems view of psychiatric disorders—Theory: A review. JAMA Psychiatry, 81(6), 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, V. G., & Wallston, K. A. (2004). The development and psychometric evaluation of the Brief Resilient Coping Scale. Assessment, 11(1), 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilkstein, G. (1978). The family APGAR: A proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. Journal of Family Practice, 6(6), 1231–1239. [Google Scholar]

- Smilkstein, G., Ashworth, C., & Montano, D. (1982). Validity and reliability of the family APGAR as a test of family function. Journal of Family Practice, 15(2), 303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Tol, W. A., Barbui, C., Galappatti, A., Silove, D., Betancourt, T. S., Souza, R., & Van Ommeren, M. (2011). Mental health and psychosocial support in humanitarian settings: Linking practice and research. The Lancet, 378(9802), 1581–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomas, J. M., Caycho-Rodríguez, T., Ventura-León, J., Sancho, P., García, C. H., & Arias, W. L. (2021). Measurement invariance of the Brief Resilient Coping Scale (BRCS) in Peruvian and Spanish older adults. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 36(4), 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Bachmann, D. (2015). Resiliencia, pobreza y ruralidad. Revista Médica de Chile, 143(5), 677–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watters, E. R., Aloe, A. M., & Wojciak, A. S. (2021). Examining the associations between childhood trauma, resilience, and depression: A multivariate meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(1), 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J., Gong, Y., Wang, X., Shi, J., Ding, H., Zhang, M., & Han, J. (2021). Gender differences in the relationships between different types of childhood trauma and resilience on depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents. Preventive Medicine, 148, 106523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weitzel, E. C., Glaesmer, H., Hinz, A., Zeynalova, S., Henger, S., Engel, C., Löffler, M., Reyes, N., Wirkner, K., Witte, A. V., Villringer, A., Riedel-Heller, S. G., & Löbner, M. (2023). Soziodemografische und soziale korrelate selbstberichteter Resilienz im alter—Ergebnisse der populationsbasierten LIFE-adult-studie. Bundesgesundheitsblatt—Gesundheitsforschung—Gesundheitsschutz, 66(4), 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, R., DeGraff, D. S., & Orozco-Rocha, K. (2023). Economic resources and health: A bi-directional cycle for resilience in old age. Journal of Aging and Health, 35(10), 767–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamora-Moncayo, E., Burgess, R. A., Fonseca, L., González-Gort, M., & Kakuma, R. (2021). Gender, mental health, and resilience in armed conflict: Listening to life stories of internally displaced women in Colombia. BMJ Global Health, 6, e005770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Kolmogorov–Smirnov (p-Value) | Shapiro–Wilk (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|

| Resilience | 0.200 | 0.156 |

| APGAR family support | 0.003 | 0.002 |

| Anxiety | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Depression | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Subjective happiness | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Variable | Resilient (M ± SD) | Non-Resilient (M ± SD) | F-Value | p-Value | η2 Parcial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APGAR | 15.60 ± 4.469 | 12.10 ± 5.434 | 17.749 | <0.001 | 0.082 |

| Anxiety | 1.21 ± 1.419 | 2.16 ± 1.771 | 12.518 | 0.001 | 0.059 |

| Depression | 1.09 ± 1.535 | 1.90 ± 1.538 | 10.644 | 0.001 | 0.051 |

| Subjective Happiness | 21.51 ± 4.685 | 16.98 ± 5.603 | 27.649 | <0.001 | 0.123 |

| Predictor | Exp(B) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Resilient coping | 0.772 | <0.001 |

| Subjective happiness | 0.864 | 0.001 |

| Anxiety | 1.447 | 0.010 |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.813 | 0.014 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Camargo, A.; Vargas, R.; Rincón-Rodríguez, A.; Jiménez, E.; Trujillo-Güiza, M. Psychosocial Factors Influencing Resilience in a Sample of Victims of Armed Conflict in Colombia: A Quantitative Study. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060816

Camargo A, Vargas R, Rincón-Rodríguez A, Jiménez E, Trujillo-Güiza M. Psychosocial Factors Influencing Resilience in a Sample of Victims of Armed Conflict in Colombia: A Quantitative Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):816. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060816

Chicago/Turabian StyleCamargo, Andrés, Rafael Vargas, Alexander Rincón-Rodríguez, Elena Jiménez, and Martha Trujillo-Güiza. 2025. "Psychosocial Factors Influencing Resilience in a Sample of Victims of Armed Conflict in Colombia: A Quantitative Study" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060816

APA StyleCamargo, A., Vargas, R., Rincón-Rodríguez, A., Jiménez, E., & Trujillo-Güiza, M. (2025). Psychosocial Factors Influencing Resilience in a Sample of Victims of Armed Conflict in Colombia: A Quantitative Study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060816