Ins and Outs of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) Intervention in Promoting Social Communicative Abilities and Theory of Mind in Children and Adolescents with ASD: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theory of Mind in People with ASD: Clinical Trajectories, Assessment, and Intervention

1.2. Behavior Intervention: Theoretical Framework and ToM Conceptualization

1.3. Scope and Research Questions

- What is the state of the art regarding the outcome of ABA intervention on ToM in children and adolescents with ASD?

- How have studies addressed maintenance and generalization issues of learning?

- Which were the most adopted teaching strategies?

- How have studies controlled experimental biases?

- Research designs, assessment, and procedural integrity adopted;

- Quality appraisal of proposals.

- How should a clinician choose a ToM training for people with ASD?

- Precursors and prerequisites;

- Alternative to the intervention (comprehensive vs. focused)?

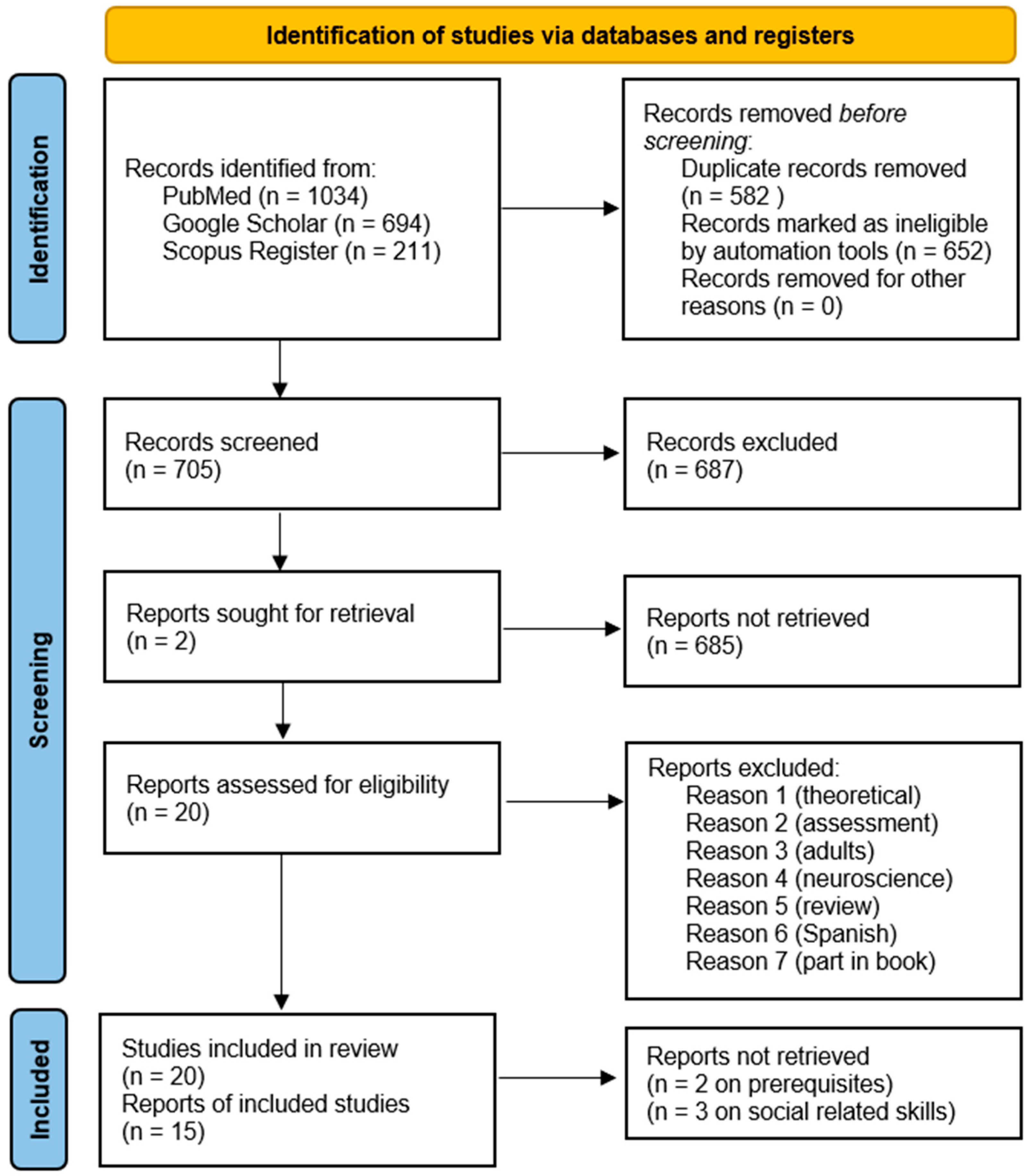

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

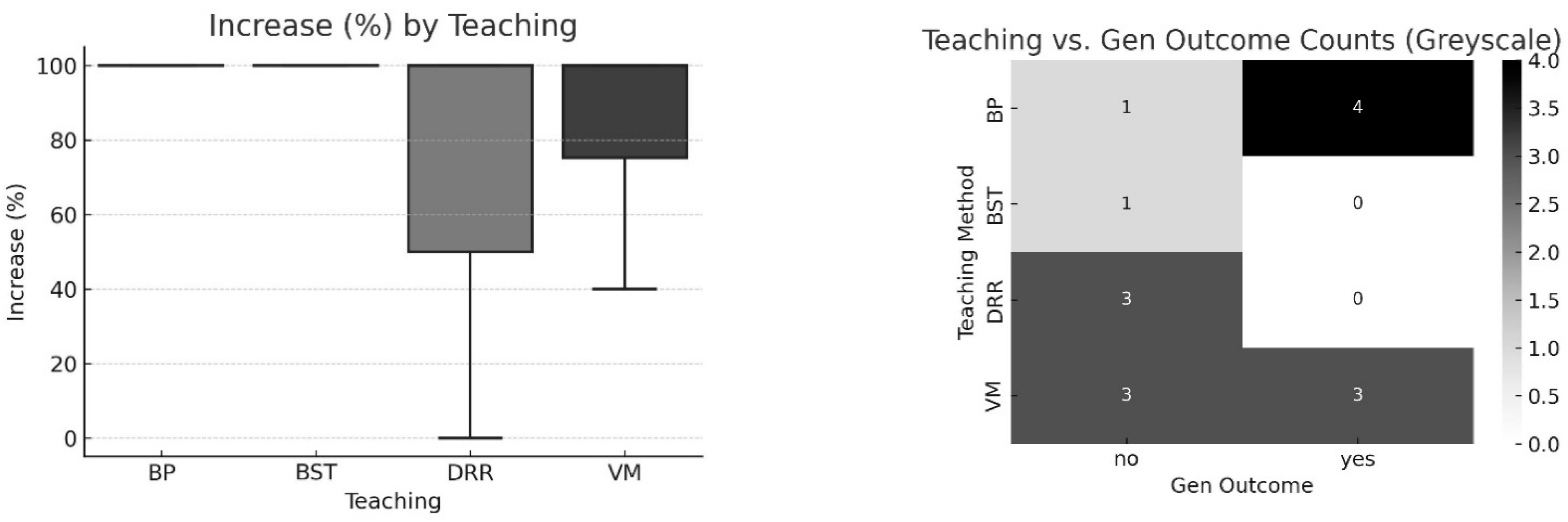

3.1. Teaching Strategies

3.1.1. Behavioral Packages

3.1.2. Behavioral Skill Training

3.1.3. Relational Frame Theory

3.1.4. Video Modeling

3.1.5. Social Skill Training

3.2. Selection of Studies: Quality Appraisal and Bias

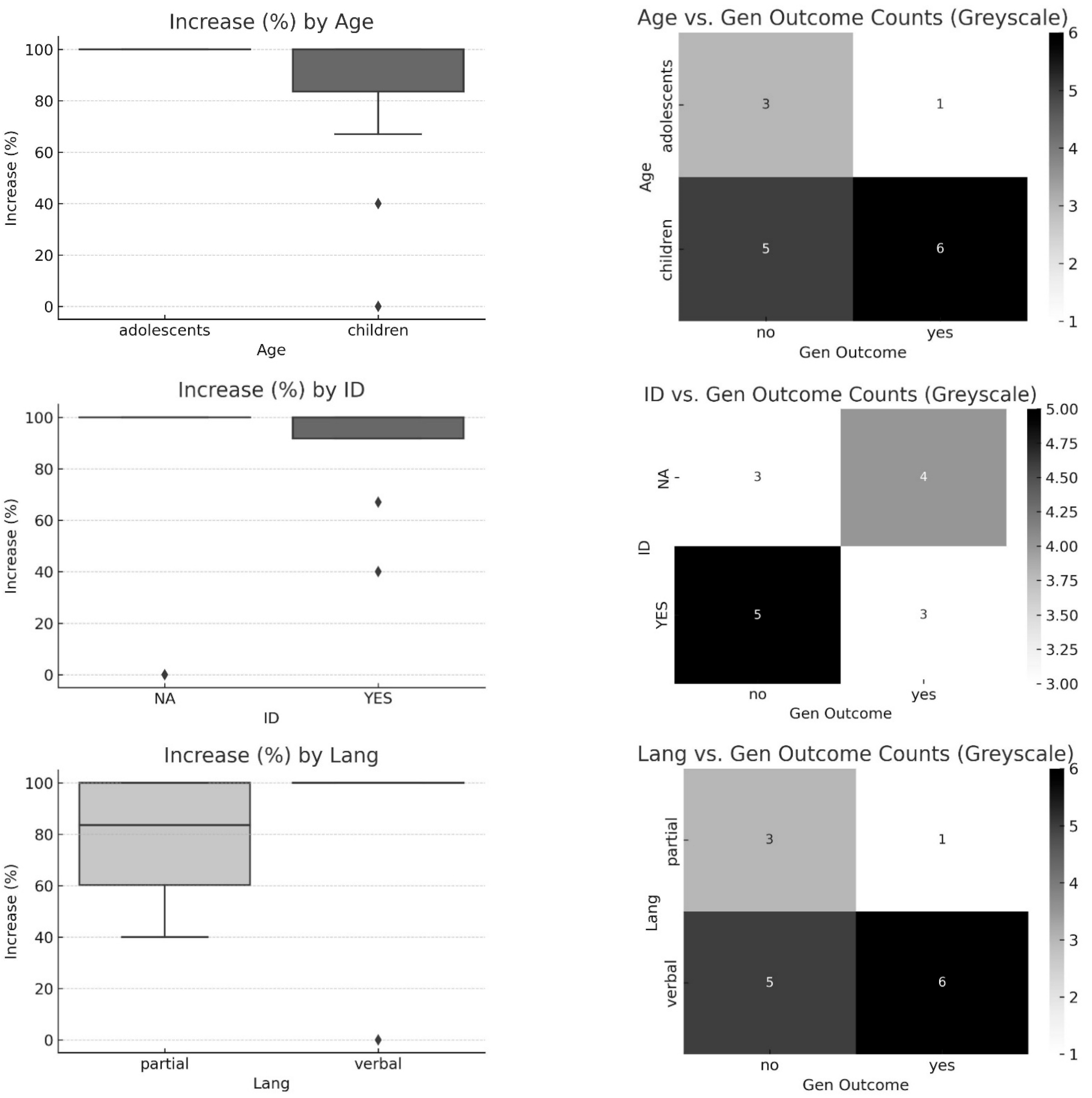

3.3. Report: Participants, Research Designs, Assessment, and Teaching Strategies

3.4. Report: Acquisition, Maintenance, Generalization, and Follow-Up

3.5. Report: Precursors and Prerequisites

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baer, D. M., Wolf, M. M., & Risley, T. R. (1987). Some still-current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 20(4), 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes-Holmes, Y., Barnes-Holmes, D., & McHugh, L. (2004). Teaching derived relational responding to young children. Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention, 1(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauminger, N. (2007). Brief report: Group social-multimodal intervention for HFASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1605–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, R. B., & Sofronoff, K. (2008). A new computerised advanced theory of mind measure for children with Asperger syndrome: The ATOMIC. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begeer, S., Gevers, C., Clifford, P., Verhoeve, M., Kat, K., Hoddenbach, E., & Boer, F. (2011). Theory of mind training in children with autism: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belisle, J., Dixon, M. R., Stanley, C. R., Munoz, B., & Daar, J. H. (2016). Teaching foundational perspective-taking skills to children with autism using the PEAK-T curriculum: Single-reversal “I–You” deictic frames. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 49(4), 965–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-Ruiz, G., Luzón-Collado, C., Arrillaga-González, J., & Lahera, G. (2022). Development of an ecologically valid assessment for social cognition based on real interaction: Preliminary results. Behavioral Sciences, 12(2), 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstrom, R., Najdowski, A. C., Alvarado, M., & Tarbox, J. (2016). Teaching children with autism to tell socially appropriate lies. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 49(2), 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D. V. (2010). Overlaps between autism and language impairment: Phenomimicry or shared etiology? Behavior Genetics, 40, 618–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlow, C., & O’Dell, L. (2009). Challenging understandings of “Theory of Mind”: A brief report. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 47(6), 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengher, M., Shamoun, K., Moss, P., Roll, D., Feliciano, G., & Fienup, D. M. (2016). A comparison of the effects of two prompt-fading strategies on skill acquisition in children with autism spectrum disorders. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Charlop-Christy, M. H., & Daneshvar, S. (2003). Using video modeling to teach perspective taking to children with autism. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 5(1), 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, B., Stead, P., & Elliot, M. (2010). Comparative genomics of autism and schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(Suppl. S1), 1736–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, E. A., DeMayo, M. M., & Guastella, A. J. (2019). Executive function in autism spectrum disorder: History, theoretical models, empirical findings, and potential as an endophenotype. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhadwal, A. K., Najdowski, A. C., & Tarbox, J. (2021). A systematic replication of teaching children with autism and other developmental disabilities correct responding to false-belief tasks. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 14, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Borda, G. A., Garcia-Zambrano, S., & Flores, E. P. (2024). Behavioral interventions for teaching perspective-taking skills: A scoping review. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 34, 100816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGennaro Reed, F. D., Blackman, A. L., Erath, T. G., Brand, D., & Novak, M. D. (2018). Guidelines for using behavioral skills training to provide teacher support. Teaching Exceptional Children, 50(6), 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziobek, I., Fleck, S., Kalbe, E., Rogers, K., Hassenstab, J., Brand, M., Kessler, J., Woike, J. K., Wolf, O. T., & Convit, A. (2006). Introducing MASC: A movie for the assessment of social cognition. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckes, T., Buhlmann, U., Holling, H. D., & Möllmann, A. (2023). Comprehensive ABA-based interventions in the treatment of children with autism spectrum disorder—A meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 23(1), 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M., Dipierro, M. T., Mondani, F., Gerardi, G., Monopoli, B., Felicetti, C., Forieri, F., Mazza, M., & Valenti, M. (2020). Developing telehealth systems for parent-mediated intervention of young children with autism: Practical guidelines. International Journal of Psychiatry Research, 3(3), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadda, R., Congiu, S., Doneddu, G., Carta, M., Piras, F., Gabbatore, I., & Bosco, F. M. (2024). Th.o.m.a.s.: New insights into theory of mind in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1461980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatta, L. M., Laugeson, E. A., Bianchi, D., Italian Peers® team support group, Laghi, F., & Scattoni, M. L. (2025). Program for the Education and Enrichment of Relational Skills (PEERS®) for Italy: A randomized controlled trial of a social skills intervention for autistic adolescents. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 55(1), 202–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H., Lo, Y. Y., Tsai, S., & Cartledge, G. (2008). The effects of theory-of-mind and social skill training on the social competence of a sixth-grade student with autism. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 10(4), 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryling, M. J., Johnston, C., & Hayes, L. J. (2011). Understanding observational learning: An interbehavioral approach. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 27, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadow, K. D., Pinsonneault, J. K., Perlman, G., & Sadee, W. (2014). Association of dopamine gene variants, emotion dysregulation and ADHD in autism spectrum disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35(7), 1658–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S., Wang, X., & Su, Y. (2023). Examining whether adults with autism spectrum disorder encounter multiple problems in theory of mind: A study based on meta-analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 30(5), 1740–1758. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, A. R., Tullis, C. A., Conine, D. E., & Fulton, A. A. (2024). A systematic review of derived relational responding beyond coordination in individuals with autism and intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 36(1), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, T. R., & Winner, E. (2012). Enhancing empathy and theory of mind. Journal of Cognition and Development, 13(1), 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, E., Tarbox, J., O’Hora, D., Noone, S., & Bergstrom, R. (2011). Teaching children with autism a basic component skill of perspective-taking. Behavioral Interventions, 26(1), 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Becerra, I., Martín, M. J., Chávez-Brown, M., & Douglas Greer, R. (2007). Perspective taking in children with autism. European Journal of Behavior Analysis, 8(1), 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graber, A., & Graber, J. (2023). Applied behavior analysis and the abolitionist neurodiversity critique: An ethical analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 16(4), 921–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillon, Q., Hadjikhani, N., Baduel, S., & Rogé, B. (2014). Visual social attention in autism spectrum disorder: Insights from eye tracking studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 42, 279–297. [Google Scholar]

- Guinther, P. M. (2022). Deictic relational frames and relational triangulation: An open letter in response to Kavanagh, Barnes-Holmes, and Barnes-Holmes (2020). The Psychological Record, 72(1), 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J. B., Bergmann, S., Brand, D., Wallace, M. D., St. Peter, C. C., Feng, J., & Long, B. P. (2023). Trends in reporting procedural integrity: A comparison. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 16(2), 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, S. L., Handleman, J. S., & Alessandri, M. (1990). Teaching youths with autism to offer assistance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 23(3), 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R., Jones, B., Gardner, P., & Lawton, R. (2021). Quality assessment with diverse studies (QuADS): An appraisal tool for methodological and reporting quality in systematic reviews of mixed- or multi-method studies. BMC Health Services Research, 21, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Hempkin, N., Sivaraman, M., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2024). Deictic relational responding and perspective-taking in autistic individuals: A scoping review. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 47(1), 107–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, H., Fealko, C., & Soares, N. (2020). Autism spectrum disorder: Definition, epidemiology, causes, and clinical evaluation. Translational Pediatrics, 9(Suppl. S1), S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. M., Khan, N., Sultana, A., Ma, P., McKyer, E. L. J., Ahmed, H. U., & Purohit, N. (2020). Prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders among people with autism spectrum disorder: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychiatry Research, 287, 112922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, K., Steinbrenner, J. R., Odom, S. L., Morin, K. L., Nowell, S. W., Tomaszewski, B., Szendrey, S., McIntyre, N. S., Yücesoy-Özkan, S., & Savage, M. N. (2021). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism: Third generation review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(11), 4013–4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M. L., Mendoza, D. R., & Adams, A. N. (2014). Teaching a deictic relational repertoire to children with autism. The Psychological Record, 64, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, D., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2020). The study of perspective-taking: Contributions from mainstream psychology and behavior analysis. The Psychological Record, 70, 581–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazdin, A. E. (2021). Single-case experimental designs: Characteristics, changes, and challenges. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 115(1), 56–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerns, C. M., Newschaffer, C. J., & Berkowitz, S. J. (2015). Traumatic childhood events and autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 3475–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupferstein, H. (2018). Evidence of increased PTSD symptoms in autistics exposed to applied behavior analysis. Advances in Autism, 4(1), 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugeson, E. A., Ellingsen, R., Sanderson, J., Tucci, L., & Bates, S. (2014). The ABC’s of teaching social skills to adolescents with autism spectrum disorder in the classroom: The UCLA PEERS® program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 2244–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugeson, E. A., & Park, M. N. (2014). Using a CBT approach to teach social skills to adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and other social challenges: The PEERS® method. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 32, 84–97. [Google Scholar]

- Leaf, J. B., Cihon, J. H., Leaf, R., McEachin, J., Liu, N., Russell, N., Unumb, L., Shapiro, S., & Khosrowshahi, D. (2022). Concerns about ABA-based intervention: An evaluation and recommendations. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52(6), 2838–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, L. A., Coates, A. M., Daneshvar, S., Charlop-Christy, M. H., Morris, C., & Lancaster, B. M. (2003). Using video modeling and reinforcement to teach perspective-taking skills to children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36(2), 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, L. A., Lund, C., Kooken, C., Lund, J. B., & Fisher, W. W. (2020). Procedures and accuracy of discontinuous measurement of problem behavior in common practice of applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13(2), 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, D. C., Valentino, A. L., & LeBlanc, L. A. (2016). Discrete trial training. In Early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorder (pp. 47–83). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, L. A., Colvert, E., Social Relationships Study Team, Bolton, P., & Happé, F. (2019). Good social skills despite poor theory of mind: Exploring compensation in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(1), 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lord, C., Elsabbagh, M., Baird, G., & Veenstra-Vanderweele, J. (2018). Autism spectrum disorder. The Lancet, 392(10146), 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKay, T., Knott, F., & Dunlop, A. W. (2007). Developing social interaction and understanding in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A groupwork intervention. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 32(4), 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makrygianni, M. K., Gena, A., Katoudi, S., & Galanis, P. (2018). The effectiveness of applied behavior analytic interventions for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A meta-analytic study. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 51, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelberg, J., Laugeson, E. A., Cunningham, T. D., Ellingsen, R., Bates, S., & Frankel, F. (2014). Long-term treatment outcomes for parent-assisted social skills training for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: The UCLA PEERS program. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 7(1), 45–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, J. L., & Goldin, R. L. (2013). Comorbidity and autism: Trends, topics and future directions. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(10), 1228–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, J. L., & Shoemaker, M. (2009). Intellectual disability and its relationship to autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30(6), 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mausbach, B. T., Moore, R., Roesch, S., Cardenas, V., & Patterson, T. L. (2010). The relationship between homework compliance and therapy outcomes: An updated meta-analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 34, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, M., Pino, M. C., Keller, R., Vagnetti, R., Attanasio, M., Filocamo, A., Le Donne, I., Masedu, F., & Valenti, M. (2022). Qualitative differences in attribution of mental states to other people in autism and schizophrenia: What are the tools for differential diagnosis? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52(3), 1283–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGhan, A. C., & Lerman, D. C. (2013). An assessment of error-correction procedures for learners with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46(3), 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, O., & Robinson, A. (2020). “Recalling hidden harms”: Autistic experiences of childhood applied behavioural analysis (ABA). Advances in Autism, 7(4), 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, L., Bobarnac, A., & Reed, P. (2011). Brief report: Teaching situation-based emotions to children with autistic spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 1423–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, A., Vernon, T., Wu, V., & Russo, K. (2014). Social skill group interventions for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishler, E. G. (1991). Research interviewing: Context and narrative. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Najdowski, A. C., Bergstrom, R., Tarbox, J., & Clair, M. S. (2017). Teaching children with autism to respond to disguised mands. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 50(4), 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najdowski, A. C., St. Clair, M., Fullen, J. A., Child, A., Persicke, A., & Tarbox, J. (2018). Teaching children with autism to identify and respond appropriately to the preferences of others during play. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 51(4), 890–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najeeb, P., & Quadt, L. (2024). Autistic well-being: A scoping review of scientific studies from a neurodiversity-affirmative perspective. Neurodiversity, 2, 27546330241233088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M., Farrell, L., Munnelly, A., & McHugh, L. (2017). Citation analysis of relational frame theory: 2009–2016. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 6(2), 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, M. C., Masedu, F., Vagnetti, R., Attanasio, M., Di Giovanni, C., Valenti, M., & Mazza, M. (2020). Validity of social cognition measures in the clinical services for autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plavnick, J. B., Sam, A. M., Hume, K., & Odom, S. L. (2013). Effects of video-based group instruction for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Exceptional Children, 80(1), 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruett, J. R., Kandala, S., Petersen, S. E., & Povinelli, D. J. (2015). Brief report: Theory of mind, relational reasoning, and social responsiveness in children with and without autism: Demonstration of feasibility for a larger-scale study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 2243–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reeve, S. A., Reeve, K. F., Townsend, D. B., & Poulson, C. L. (2007). Establishing a generalized repertoire of helping behavior in children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40(1), 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichow, B., Barton, E. E., Boyd, B. A., & Hume, K. (2012a). Early intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI) for young children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 10, CD009260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichow, B., Steiner, A. M., & Volkmar, F. (2012b). Social skills groups for people aged 6 to 21 with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Campbell Systematic Reviews, 8(1), CD008511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riden, B. S., Ruiz, S., Markelz, A. M., Sturmey, P., Ward-Horner, J., Fowkes, C., Wikel, K., Chitiyo, A., & Williams, M. (2024). The component analysis experimental method: A mapping of the literature base. European Journal of Behavior Analysis, 25(1), 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, K. A., Tarbox, J., & Tarbox, C. (2023). Compassion in autism services: A preliminary framework for applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 16(4), 1034–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Norton, A. H., Shkedy, G., & Shkedy, D. (2019). How much compliance is too much compliance: Is long-term ABA therapy abuse? Cogent Psychology, 6(1), 1641258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlinger, H. D. (2009). Theory of mind: An overview and behavioral perspective. The Psychological Record, 59, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmick, A. M., Stanley, C. R., & Dixon, M. R. (2018). Teaching children with autism to identify private events of others in context. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 11, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrandt, J. A., Townsend, D. B., & Poulson, C. L. (2009). Physical activity in homes 13 teaching empathy skills to children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42(1), 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreibman, L., Dawson, G., Stahmer, A. C., Landa, R., Rogers, S. J., McGee, G. G., Kasari, C., Ingersoll, B., Kaiser, A. P., Bruinsma, Y., McNerney, E., Wetherby, A., & Halladay, A. (2015). Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: Empirically validated treatments for autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 2411–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz Offek, E., & Segal, O. (2022). Comparing theory of mind development in children with autism spectrum disorder, developmental language disorder, and typical development. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 18, 2349–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidman, M., Wynne, C. K., Maguire, R. W., & Barnes, T. (1989). Functional classes and equivalence relations. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 52(3), 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silani, G., Bird, G., Brindley, R., Singer, T., Frith, C., & Frith, U. (2008). Levels of emotional awareness and autism: An fMRI study. Social Neuroscience, 3(2), 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, G. L., Ioannou, S., Smith, J. V., Corbett, B. A., Lerner, M. D., & White, S. W. (2021). Utility of an observational social skill assessment as a measure of social cognition in autism. Autism Research, 14(4), 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slocum, T. A., Pinkelman, S. E., Joslyn, P. R., & Nichols, B. (2022). Threats to internal validity in multiple-baseline design variations. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 45(3), 619–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauch, T. A., Plavnick, J. B., Sankar, S., & Gallagher, A. C. (2018). Teaching social perception skills to adolescents with autism and intellectual disabilities using video-based group instruction. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 51(3), 647–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, I. (2013). A recent behaviour analytic approach to the self. European Journal of Behavior Analysis, 14(2), 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, R. L., McDonald, S., Perdices, M., Togher, L., Schultz, R., & Savage, S. (2008). Rating the methodological quality of single-subject designs and n-of-1 trials: Introducing the Single-Case Experimental Design (SCED) Scale. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 18(4), 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taurines, R., Schwenck, C., Westerwald, E., Sachse, M., Siniatchkin, M., & Freitag, C. (2012). ADHD and autism: Differential diagnosis or overlapping traits? A selective review. ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 4, 115–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetreault, A. S., & Lerman, D. C. (2010). Teaching social skills to children with autism using point-of-view video modeling. Education and Treatment of Children, 33(3), 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, M., Mazza, M., Arduino, G. M., Keller, R., Le Donne, I., Masedu, F., Romano, G., & Scattoni, M. L. (2023). Diagnostic assessment, therapeutic care and education pathways in persons with autism spectrum disorder in transition from childhood to adulthood: The Italian National Ev. A Longitudinal Project. Annali dell’Istituto Superiore di Sanita, 59(4), 304–312. [Google Scholar]

- Vivanti, G., & Stahmer, A. C. (2021). Can the early start denver model be considered ABA practice? Behavior Analysis in Practice, 14(1), 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellman, H. M. (2018). Theory of mind: The state of the art. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 15(6), 728–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, F., Najdowski, A. C., Strauss, D., Gallegos, L., & Fullen, J. A. (2019). Teaching a perspective-taking component skill to children with autism in the natural environment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 52(2), 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whalen, C., & Schreibman, L. (2003). Joint attention training for children with autism using behavior modification procedures. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44(3), 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Liu, Z., Gong, S., & Wu, Y. (2022). The relationship between empathy and attachment in children and adolescents: Three-level meta-analyses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C. L., & Wellman, H. M. (2023). All humans have a ‘theory of mind’. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53(6), 2531–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors/Year | Country | Sample | Comorbidity | Age | Model | Target | Design | IOA | Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harris et al. (1990). | USA | 3 (males) | ID | 14–19 | ABA | Helping | MBD+P | YES | NA |

| Schrandt et al. (2009). | USA | 4 (3 male) | ID | 4–8 | ABA | Identifying emotion | MBD | YES | NA |

| Gould et al. (2011). | USA | 3 (2 male) | NA | 4–9 | ABA | Detecting eye gazing | MBD concur. | YES | NA |

| Jackson et al. (2014). | USA | 5 (males) | NA | 5–6 | ABA/RFT | Perspective-taking | MBD+P | YES | NA |

| Najdowski et al. (2017). | USA | 3 (2 male) | NA | 9 | ABA | Responding to disguised mands | MBD | YES | NA |

| Dhadwal et al. (2021). | USA | 3 (males) | DD | 4–9 | ABA | Perspective-taking | MBD | YES | NA |

| Najdowski et al. (2018). | USA | 3 (1 male) | NA | 5–8 | ABA | Identify and respond to others’ preferences | MBD | YES | NA |

| Welsh et al. (2019). | USA | 3 (1 male) | NA | 6–8 | ABA | to tact others’ private events | MBD | YES | NA |

| Bergstrom et al. (2016). | USA | 3 (2 male) | NA | 5 | ABA/BST | Use socially appropriate lies | MBD | YES | NA |

| Belisle et al. (2016). | USA | 3 (males) | ID | 12–18 | ABA/RFT | perspective-taking tasks | MBD+P | YES | NA |

| Schmick et al. (2018). | USA | 3 (males) | NA | 13–17 | ABA/RFT | Identification of private events | MBD+P | YES | NA |

| LeBlanc et al. (2003). | USA | 3 (males) | NA | 7–13 | ABA | Perspective-taking | MBD+P | YES | YES |

| Charlop-Christy and Daneshvar (2003). | USA | 3 (males) | ID | 6–9 | ABA | Perspective-taking | MBD + whitin | YES | NA |

| Reeve et al. (2007). | USA | 4 (3 male) | ID | 5–6 | ABA | Helping | MBD | YES | NA |

| Gómez-Becerra et al. (2007). | USA | 15 ASD, TDC, DS | ID | 4–8 | ABA/RFT | Perspective-taking | Intra/intersubject | YES | NA |

| Tetreault and Lerman (2010). | USA | 3 (2 male) | ID/Language | 4–8 | ABA | Social engagement | MBD | YES | YES |

| McHugh et al. (2011). | USA | 3 (males) | NA | 5 | ABA | Recognizing emotion | MBD | YES | NA |

| Plavnick et al. (2013). | USA | 4 (2 male) | ID/OCD | 13–16 | ABA/SST | Social engagement | MPDB | YES | NA |

| Stauch et al. (2018). | USA | 5 (3 male) | ID | 15–17 | ABA/SST | Conversation | MPD | YES | NA |

| Feng et al. (2008). | USA | 1 (male) | behavioral | 11 | ABA/SST | Perspective-taking | MPDB | YES | YES |

| Selected Studies | 1. Background | 2. Research Aim/s | 3. Research Setting and Population | 4. The Study Design | 5. Appropriate Sampling | 6. Rationale of Data Collection | 7. The Format of the Data Collection Tool | 8. Description of Data Collection Procedure | 9. Recruitment Data Provided | 10. Justification for the Analytic Method | 11. The Method of Analysis | 12. Evidence | 13. Strengths and Limitations | Quality Scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harris et al. (1990) | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2.2 |

| Schrandt et al. (2009) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2.5 |

| Najdowski et al. (2017) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2.7 |

| Dhadwal et al. (2021) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2.7 |

| Najdowski et al. (2018) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2.7 |

| Bergstrom et al. (2016) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2.7 |

| Belisle et al. (2016) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2.6 |

| Schmick et al. (2018) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2.5 |

| LeBlanc et al. (2003) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2.7 |

| Charlop-Christy and Daneshvar (2003) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2.7 |

| Reeve et al. (2007) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2.8 |

| Gómez-Becerra et al. (2007) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2.8 |

| McHugh et al. (2011) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2.5 |

| Feng et al. (2008) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2.7 |

| Jackson et al. (2014) | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2.0 |

| Quality Scores | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.6 |

| Selected Studies | 1. Clinical History Was Specified. (Age, Sex, Etiology and Severity) | 2. Target Behaviors. Precise and Repeatable Measures That Are Operationally Defined | 3. Design 1: 3 Phases. The Study Must Be Either A-B-A or Multiple Baseline | 4. Design 2: Baseline (Pre-Treatment Phase). Sufficient Sampling Was Conducted | 5. Design 3: Treatment Phase. Sufficient Sampling Was Conducted | 6. Design 4: Data Record. Raw Data Points Were Reported | 7. Observer Bias: Inter-rater Reliability Was Established for at Least One Measure of Target Behavior | 8. Independence of Assessors | 9. Statistical Analysis | 10. Replication: Either Across Subjects, Therapists or Settings | 11. Evidence for Generalization | Bias (Items Failed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harris et al. (1990) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | 2 |

| Schrandt et al. (2009) | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | 2 |

| Najdowski et al. (2017) | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | 2 |

| Dhadwal et al. (2021) | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | 2 |

| Najdowski et al. (2018) | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | 3 |

| Bergstrom et al. (2016) | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | 3 |

| Belisle et al. (2016) | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | 2 |

| Schmick et al. (2018) | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | 3 |

| LeBlanc et al. (2003) | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | 4 |

| Charlop-Christy and Daneshvar (2003) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | 3 |

| Reeve et al. (2007) | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | 3 |

| Gómez-Becerra et al. (2007) | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 2 |

| McHugh et al. (2011) | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | 3 |

| Feng et al. (2008) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | 2 |

| Jackson et al. (2014) | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | 3 |

| Bias (items failed) | 10 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 5 | 7 | 2.6 |

| Authors | ID | Assess. | Sample | Age | Model | Setting | Target | Design | Teaching | Increase | Gen. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harris et al. (1990). | YES | Extern. +PPVT | 3 (males) | 14–19 | ABA | home/school/office | helping | MBD+P | Prompting | 3 | − (trials) |

| Schrandt et al. (2009). | YES | Extern. | 4 (3 male) | 4–8 | ABA | home/school | identifying emotion | MBD | P. Delay Behavior Rehearsal | 4 | + |

| Jackson et al. (2014). | NA | CARS | 5 (males) | 5–6 | ABA/RFT | home | perspective-taking | MBD+P | DRR | 0 | − (trials) |

| Najdowski et al. (2017). | NA | Extern. | 3 (2 male) | 9 | ABA | home/natural | respond to disguised mands | MBD | MET role play rules | 3 | + |

| Dhadwal et al. (2021). | YES | Extern. | 3 (males) | 4–9 | ABA | center/home | perspective-taking | MBD | MET Prompting R+ | 3 | + |

| Najdowski et al. (2018). | NA | Extern. | 3 (1 male) | 5–8 | ABA | community | perspective-taking | Pre-Post | MET rules feedback | 3 | + |

| Bergstrom et al. (2016). | NA | Extern. | 3 (2 male) | 5 | ABA | home | telling lies | MBD | BST | 3 | − (trials) |

| Belisle et al. (2016). | YES | Extern. | 3 (males) | 12–18 | ABA/RFT | special school | relational responding | MBD+P | PEAK/ DRR | 3 | − (subjects) |

| Schmick et al. (2018). | NA | Extern. | 3 (males) | 13–17 | ABA/RFT | special school | recognizing emotion | MBD+P | PEAK/ DRR | 3 * | − (setting) |

| LeBlanc et al. (2003). | NA | Extern. | 3 (males) | 7–13 | ABA | special school | perspective-taking | MBD+P | VM | 3 * | − (setting) |

| Charlop-Christy & Daneshvar (2003). | YES | Extern. +PPVT | 3 (males) | 6–9 | ABA | center | perspective-taking | MBD + whitin | VM | 2 * | − (subjects) |

| Reeve et al. (2007). | YES | Extern. | 4 (3 male) | 5–6 | ABA | special school | helping | MBD | VM package | 4 | + |

| Gómez-Becerra et al. (2007). | YES | WPPSI | 15 ASD, TDC, DS | 4–8 | ABA/RFT | home/school/center | perspective-taking | Intra/intersubject | VM error corr. | 2 | − (setting) |

| McHugh et al. (2011). | NA | Extern. | 3 (males) | 5 | ABA | home | recognizing emotion | MBD | VM/DTT Prompting error corr. | 3 | + |

| Feng et al. (2008). | NA | WISC | 1 (male) | 11 | ABA/SST | school | perspective-taking | MPDB | VM role play feedback | 1 | + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Esposito, M.; Fadda, R.; Ricciardi, O.; Mirizzi, P.; Mazza, M.; Valenti, M. Ins and Outs of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) Intervention in Promoting Social Communicative Abilities and Theory of Mind in Children and Adolescents with ASD: A Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 814. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060814

Esposito M, Fadda R, Ricciardi O, Mirizzi P, Mazza M, Valenti M. Ins and Outs of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) Intervention in Promoting Social Communicative Abilities and Theory of Mind in Children and Adolescents with ASD: A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):814. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060814

Chicago/Turabian StyleEsposito, Marco, Roberta Fadda, Orlando Ricciardi, Paolo Mirizzi, Monica Mazza, and Marco Valenti. 2025. "Ins and Outs of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) Intervention in Promoting Social Communicative Abilities and Theory of Mind in Children and Adolescents with ASD: A Systematic Review" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 814. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060814

APA StyleEsposito, M., Fadda, R., Ricciardi, O., Mirizzi, P., Mazza, M., & Valenti, M. (2025). Ins and Outs of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) Intervention in Promoting Social Communicative Abilities and Theory of Mind in Children and Adolescents with ASD: A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 814. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060814